Abstract

Background

A positive family history of alcohol use disorders (FH) is a robust predictor of personal alcohol abuse and dependence. Exposure to problem-drinking models is one mechanism through which family history influences alcohol-related cognitions and drinking patterns. Similarly, exposure to alcohol advertisements is associated with alcohol involvement and the relationship between affective response to alcohol cues and drinking behavior has not been well established. In addition, the collective contribution that FH, exposure to different types of problem-drinking models (e.g., parents, peers), and personal alcohol use have on appraisal of alcohol-related stimuli has not been evaluated with a large sample.

Objective

We investigated the independent effects of FH, exposure to problem-drinking models, and personal alcohol use on valence ratings of alcohol pictures in a college sample.

Method

College students (N=227) completed measures of personal drinking and substance use, exposure to problem-drinking models, FH, and ratings on affective valence of 60 alcohol pictures.

Results

Greater exposure to non-familial problem-drinkers predicted greater drinking among college students (β = .17, p < .01). However, personal drinking was the only predictor of valence ratings of alcohol pictures (β= −.53, p < .001).

Conclusions

Personal drinking level predicted valence ratings of alcohol cues over and above FH, exposure to problem-drinking models, and demographic characteristics. This suggests that positive affective responses to alcohol pictures are more a function of personal experience (i.e., repeated heavy alcohol use) than vicarious learning.

Individuals with a positive family history of alcohol abuse or dependence (FH) are at high risk for developing alcohol use disorders (AUD) themselves (Bohman et al., 1987; Cloninger et al., 1981; Goodwin, 1979; Schuckit, 1985). The FH-related risk of developing drinking problems has biological and environmental components (Cleveland and Wiebe, 2003b; Cloninger et al., 1981; McMorris et al., 2002), the latter involving exposure to familial (e.g., parental) problem-drinking models (Brown et al., 1999; Ullman and Orenstein, 1994) as well as non-biological models (e.g., peers) (Andrews et al., 2002; Bot et al., 2005; Cleveland and Wiebe, 2003a). Few studies have examined the differential effects of exposure to various problem-drinking models simultaneously (Leonard and Mudar, 2000; Reifman et al., 1998; Urberg et al., 1997). Similarly, a handful of studies have examined affective response to alcohol cues in detoxified alcoholics (Heinz et al. 2007; Wrase et al. 2002), but the relationship with level of alcohol intake is unknown. The present study focused on determining the relationship between FH, exposure to different types of problem-drinking models, personal alcohol use, and subjective valence ratings of alcohol cues (e.g., advertisements).

Many studies have shown that FH influences drinking (Cloninger et al., 1981; Cloninger et al., 1986; Goodwin, 1979; Kendler et al., 1997; Schuckit, 1985). For example, the effects of FH on personal alcohol drinking among college students were examined in a longitudinal study (Jackson et al., 2000), showing that offspring of alcohol dependent individuals were more likely to develop and maintain persistent AUD themselves. Bohman reported increased rates of alcohol abuse among biological offspring of adults with AUD (Bohman et al., 1987; 1981). Specific genes that influence the development of alcohol-related problems have been identified (Dick et al., 2002; Dick et al., 2007; Wall et al., 1999), indicating the important role of biological factors in the escalation and maintenance of problem drinking and AUD. While inherited biological traits are critical, the mechanisms through which FH increases risk for offspring drinking problems are still not completely understood, but one component can be parental modeling.

According to learning theory, modeling is the process of acquiring new behaviors, skills, and attitudes through the observation and the imitation of other people’s behaviors (Bandura, 1986). Modeling also depends on the contingencies that the act has on the actor (Schunk, 1987). To understand the effect of exposure to problem-drinking family models on personal drinking, it is necessary to partial out the effect of problem-drinking peer models, since peer models influence alcohol use initiation and earlier onset of heavy drinking (Bot et al., 2005; Reifman et al., 1998; Swadi, 1999; Urberg et al., 1997). It is notable that studies in this arena have focused on problem-drinking friends (e.g., Curran et al., 1997) often to the exclusion of other potentially influential same-generation problem-drinking models (e.g., acquaintances, roommates, boyfriend/girlfriend, dorm hall neighbors). For example, Leonard and Mudar (2000) found that young adult newlyweds’ drinking was significantly correlated with their respective friends’ alcohol use. Andrews and colleagues (2002) found a correlation between young adult binge drinking and peer alcohol use. Here, the observer’s perception of peer alcohol use, rather than actual peer use, predicted personal drinking.

Although the importance of familial problem-drinking models in conjunction with peer and other individuals’ modeling has been recognized (Leonard and Mudar, 2000; Reifman et al., 1998; Urberg et al., 1997), it has not been fully investigated. Specifically, studies on model influence have focused on the effects of predetermined dyads (e.g., Yu, 2003), triads (e.g., Fromme and Ruela, 1994; Leonard and Mudar, 2000), or groups of individuals (e.g., Oostveen et al., 1996) without simultaneously investigating the effect of exposure to different types of problem-drinking models on drinking. Similarly, the differential effect of exposure to familial models from the same (i.e., siblings) and different (i.e., parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents) generations had not quite been investigated.

Alcohol cue reactivity is also an important predictor of alcohol use. For instance, one ubiquitous alcohol cue, alcohol advertisements, appears to exert a modest influence on personal drinking practices. Atkin (1983) and colleagues studied adolescents and adults (age range 12 to 22 years), and found a moderate positive relationship between daily exposure to alcohol advertisements and personal alcohol use. Snyder (2006) found that alcohol advertisement expenditures predicted youth (age range 15 to 26) alcohol use and escalation. These findings suggest that affective response (i.e., pleasant versus unpleasant) to alcohol advertisements may be an important factor in the maintenance and progression of alcohol use for youth.

For this reason, it is important to understand the relationship between affective response to alcohol beverage cues and personal alcohol involvement. The few studies investigating valence ratings to alcohol cues present a limited opportunity to assess the relationship with level of alcohol use because they have only included alcohol dependent participants (Heinz et al. 2007; Wrase et al. 2002). Grusser, Heinz, and Flor (2000) reported assessing the valence of alcohol beverage pictures among individuals having a variety of substance dependence diagnoses, but did not report alcohol valence rating results.

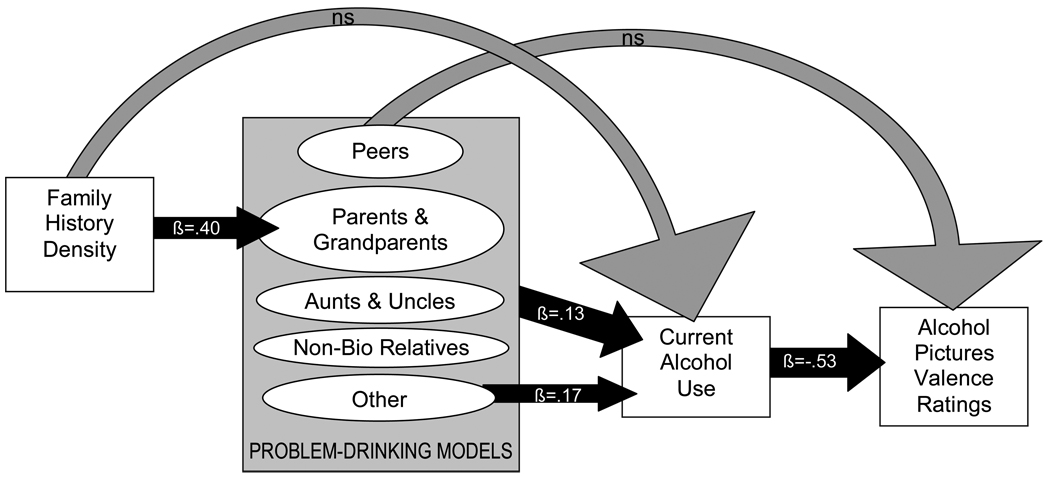

The goal of the present study was to investigate the effects of different problem-drinking models (i.e., familial, peer, and other), FH, and personal alcohol use on affective response to alcohol cues. First, we hypothesized that alcohol cue valence ratings would be positively predicted by personal drinking, specifically that heavy drinkers would rate alcohol stimuli more positively. Second, based on the young adult substance use literature (e.g., Andrews et al., 2002), we hypothesized that personal alcohol use would be positively predicted by exposure to peer problem-drinking models, and that alcohol use would mediate the relationship between exposure to peer problem-drinking models and alcohol cue valence ratings. Finally, it was hypothesized that density of FH would relate to exposure to biological problem-drinking parents and grandparents models, but not non-biological models, and predict personal drinking (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model predicting alcohol pictures valence ratings. Black arrows indicate confirmed relationships (p<.05). Gray arrows indicate hypothesized but unconfirmed relationship.

Method

Participants

Two hundred forty five undergraduate students were recruited through psychology experiment scheduling websites of two local universities to participate in a beverage picture rating study. Participants were between 18 and 24 years of age; both genders and all ethnicities were included. Data from 18 participants were incomplete; these participants were not administered (n=7) or did not complete (n=1) all measures or, because of technical difficulties, alcohol valence ratings were incomplete (n=10). These participants were excluded from study, yielding a final sample of 227 participants (46% female, range 18 to 23 years, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographic, substance use, and problem-drinking exposure characteristics (N=227)

| Independent variables | M (SD) or % | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.86 (1.27) | 18–23 |

| Female | 46% | |

| Caucasian | 59% | |

| Education completed (years) | 12.66 (1.01) | |

| Density of family history of AUD a | 0.62 (0.17) | 0.25–1.00 |

| Age when regular alcohol use started | 16.76 (1.39) | 13–21 |

| Drinks per month | 62.64 (107.13) | 0–660 |

| BDI-II total score | 7.73 (6.96) | 0–49 |

| Mean alcohol pictures valence ratings | 4.48 (1.08) | 1.5–8.5 |

| Indices of exposure to problem-drinking models b | ||

| 31% Biological parents and grandparents | 0.50 (0.33) | 0.05–1.00 |

| 17% Biological aunts and uncles | 0.27 (0.24) | 0.05–1.00 |

| 12% Biological siblings and cousins | 0.20 (0.16) | 0.05–0.73 |

| 3% Non-biological relatives | 0.40 (0.21) | 0.17–0.72 |

| 26% Peers | 0.15 (0.11) | 0.05–0.56 |

| 6% Other | 0.24 (0.26) | 0.05–1.00 |

Mean reflects only participants endorsing FH for AUD

Percentages reflect portion of participants who endorsed each category

Measures and Stimuli

Demographics

A self-report form gathered general demographic and health information.

Mood

Current level of depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report measure (Beck et al., 1996). For each item, participants endorsed one of four sentences arranged in ascending severity (O'Hara et al., 1998). The BDI-II has demonstrated good psychometric properties with college samples (Storch et al., 2004; Whisman et al., 2000).

Family history of alcohol use disorders

History of AUD for all biological first- and second-degree relatives was assessed with a 22-item form (Brown et al., 1989) based on DSM-IV criteria and Schuckit's problem list (Schuckit et al., 1988). A family history index was computed; each biological parent with AUD added 0.50 to the score, while each biological grandparent with AUD added 0.25 (Stoltenberg et al., 1998).

Exposure to alcohol use models

The History of Exposure to Problem-Drinking Models evaluated participants’ exposure to individuals identified as having problems related to their alcohol use (Brown et al., 1999). Participants were asked to list all individuals they have seen drinking too much or having alcohol related problems. For each individual listed, participants were asked to indicate at what age they were exposed to this person at least once per week (or at least 52 days in a year). A global exposure index was computed using the number of years of exposure divided by the participant’s age (Brown et al., 1999), so that a score of 1 indicated exposure for the participant’s entire lifetime. Similarly, specific exposure indices were calculated for: (1) biological parents and grandparents, (2) biological aunts and uncles, (3) biological siblings and cousins (same generation), (4) non-biological relatives (e.g., stepparents), (5) peers (e.g., friends and roommates), and (6) other non-related non-“friend” individuals (e.g., neighbors, classmates, friends’ significant others, non-relatives).

Substance use history

Personal alcohol and other substance use history was obtained with the brief Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR), a self-report measure assessing age of onset, lifetime episodes, recency, quantity, and frequency of alcohol use as well as each other substance type. The CDDR has demonstrated good reliability and validity with adolescents and young adults (e.g., Brown et al., 2001; Brown et al., 1998). An index of recent drinking was computed by multiplying the average number of drinking occasions per month in the past 3 months, by the number of average standard alcohol drinks consumed per occasion. A standard drink was defined as a 12 oz. beer, 4 oz. glass of wine, or 1 1/4 oz. of spirits.

Alcohol stimuli

The alcohol beverage stimuli consisted of 60 color pictures of beer/malt liquor, wine, and hard liquor (see Figure 2 for an example). Pictures were primarily advertisements obtained from popular magazines and the internet, but also included were images from product websites, amateur photographs, the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) (Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 1999), and the Normative Appetitive Picture System (NAPS) (Stritzke et al., 2004). Pictures inclusion required acceptable visual attributes (e.g., clarity, color) and a prime focus on the beverage, while exclusionary criteria were any of the following subject matter: celebrities; aggressive, seductive, or sexual situations.

Figure 2.

Sample stimulus from the Normative Appetitive Picture System (Stritzke et al., 2004)

Rating system

The Self-Assessment Manikin (Lang, 1999) picture-rating system assessed valence ratings for each picture. Valence is defined as the amount of pleasure/displeasure perceived while viewing the picture. For each picture, subjects rated valence on a 9-point scale ranging from positive to negative (Lang, 1999).

Procedures

Participants were tested in groups of 1 to 7 at a time (average = 4) in a quiet room in the psychology department on campus. To maintain privacy and confidentiality, participants were uniformly spaced within the room prior to data collection. Data reported here were collected as part of a larger beverage picture standardization study. Data collection included four parts. First, participants were informed about the nature of the study and informed consent was obtained. Informed consents were approved by the Human Research Protections Programs of the University of California San Diego and San Diego State University. Second, questionnaires on demography, mood state, and personal substance use history were administered.

Third, participants completed valence ratings of the pictures. Pictures were programmed in E-Prime (Pittsburgh, PA) for systematic presentation. Four picture presentation programs were created, and within each program, pictures were randomized to control for order effects. One program was administered during each session, so that each subject rated 30 alcohol pictures. The four programs were rotated an average of thirteen times during the study, yielding an average of 113 (range 91 to 136) participant ratings for each of the 60 pictures. Participants used personal Self-Assessment Manikin booklets (Lang, 1999) to indicate valence picture ratings. Detailed procedures for using the booklet and practice trials were provided prior to rating the pictures. Stimuli were presented on a projector screen via a laptop, and each trial included three components: 1) the preparation slide (“Please be ready for the next slide”) presented for 3 seconds; 2) a stimulus picture presented for 6 seconds with participants asked to attend to it during its entire presentation; and 3) a rating slide presented for 11 seconds asking participants to rate how the picture made them feel while viewing it.

Following the picture ratings, participants completed structured interviews assessing family history of alcohol and drug use disorders and history of exposure to problem-drinking models. Then, participants were provided with their choice of a non-alcoholic beverage, debriefed about the study, and given information about health risks of alcohol use as well as substance misuse policy handouts for their campus. After completing the session, participants were awarded class credit.

Data Analysis

Alcohol picture ratings data were coded and entered into Microsoft Excel, checked for accuracy, and exported into SPSS 12.0. All data were double checked and examined for outliers, normality of distribution, and homocedasticity. Hierarchical regressions determined whether: 1) current personal alcohol use (defined as number of drinks consumed per month on average over the past 3 months) predicted alcohol pictures valence ratings, 2) exposure to different types of problem-drinking models predicted personal alcohol use and alcohol pictures valence ratings, and 3) FH density predicted exposure to biological problem-drinking models and personal alcohol drinking. The first step of each hierarchical regression included covariates that correlated with independent or dependent variables in the model (see Table 2 for correlation matrix). In analyses examining exposure indices as predictors, all exposure indices were entered in the same step.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between demographic characteristics, substance use, and alcohol picture valence ratings (N=227)

| Variables: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (females=1, males=2) | |||||||||

| 2. Ethnicity (Caucasian=1, Non-Caucasian=2) | −.09 | ||||||||

| 3. Age | .12 | .20** | |||||||

| 4. BDI-II total | −.19** | .05 | −.09 | ||||||

| 5. FH density of AUD | −.14* | −.02 | −.07 | .06 | |||||

| 6. Exposure to bio parents & grandparents | −.16* | −.08 | −.08 | .14* | .41** | ||||

| 7. Exposure to peers | .02 | −.07 | −.04 | −.06 | .02 | .02 | |||

| 8. Exposure to other individuals | −.09 | .04 | −.04 | .13 | .04 | −.06 | −.02 | ||

| 9. Drinks per month | .08 | −.21** | −.15* | .07 | .01 | .05 | −.06 | .34** | |

| 10. Alcohol pictures mean valence | −.09 | .18** | .09 | .02 | .01 | −.05 | −.07 | −.12 | −.31** |

p < .05

p < .01

Results

The recent drinking variable (drinks per month in the past 3 months) was skewed, so transformation using the natural log was applied (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007).

Of the 227 participants, 14% indicated a FH, 62% reported exposure to problem-drinking models, and 14% scored in the elevated range for depressed mood (BDI-II total ≥ 13). Most participants (65%, n=147) reported drinking less than once per week. Of these, 61% reported having drank at least some alcohol in the past 3 months (n=89) and drinking on 3.19 ± 4.74 (M ± SD) occasions per month with 2.70 ± 3.02 drinks per occasion, and 53% (n= 74) reported never having been drunk. The other 35% (n=80) reported using alcohol weekly or more, drinking on 11.40 ± 8.29 occasions per month with 8.40 ± 7.50 drinks per occasion, and 13% (n=10) reported never having been drunk.

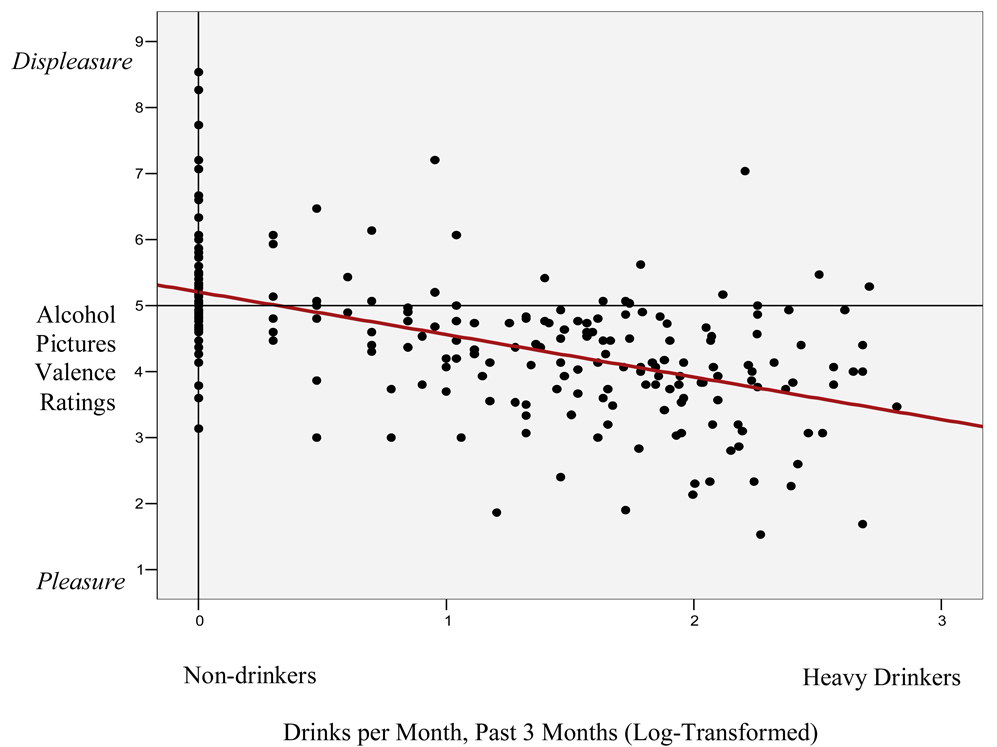

Personal Recent Drinking

Recent alcohol drinking (i.e., drinks per month in the past 3 months) predicted alcohol pictures valence ratings (F 4, 220 = 22.93, p < .001; β= −.53, p < .001) over and above age and ethnicity (see Figure 3), which correlated with the dependent and independent variables (see Table 2). Because exposure to problem-drinking models was not related to valence ratings (global index of exposure, β= −.12, ns), mediation was not supported.

Figure 3.

Results from linear regression analysis in which current alcohol use predicted alcohol picture valence ratings.

Exposure to Problem-Drinking Models

The global index of exposure to problem-drinking models significantly predicted recent drinking (F 5, 220 = 8.83, p < .001; β = .13, p < .05). When analyzed at the component level, exposure to non-peer/non-familial (e.g., neighbors, “other”) problem-drinking individuals (β = .17, p < .01) predicted recent drinking over and above participants characteristics, while exposure to all other types of problem-drinking models did not predict drinking: biological parents and grandparents (β = .08, ns), aunts and uncles (β = .02, ns), siblings and cousins (β = .01, ns), non-biological relatives (β = .08, ns), and peers (β = − .03, ns).

Since exposure to “other” (i.e., non-peer, non-familial) problem-drinking models was a significant predictor of recent drinking, we conducted follow-up analyses to characterize those who endorsed this form of exposure. Those endorsing exposure to “other” (n=13) versus those not endorsing such exposure (n=214) were compared using independent samples t-tests. Groups did not differ in FH density (t (13) = −.84, ns), recent alcohol use (t (225) = −1.35, ns), or years of regular alcohol use (t (103) = −.71, ns). However, those reporting exposure to other problem-drinking models reported more depressive symptomatology (11.40 ± 4.15 versus 7.51 ± 7.04, t (224) = −1.96, p<.05) and were younger (18.38 ± 0.65 versus 18.89 ± 1.29, t (18) = 2.51, p < .05) than those who did not report exposure to “other” models.

Family History Density

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed that FH density was associated with the global index of exposure to problem-drinking models (F 3, 217 = 9.11, p < .001; β = .28, p < .001). Not surprisingly, FH density was associated with exposure to parent and grandparent problem-drinking models (F 3, 217 = 18.20, p < .001; β = .40, p < .001) over and above covariates that correlated with the dependent or independent variables (i.e., gender and BDI-II total). FH density was not associated with exposure to biological uncles and aunts (β = −.08, ns), or siblings and cousins (β= .04, ns). As expected, regression analyses confirmed that FH density was not linked with exposure to peer (β = .02, ns), non-biological relatives (β = −.05, ns), or other (β = .04, ns) problem-drinking models.

Further, FH density (β= −.01, ns) did not predict picture valence ratings, and did not predict college students’ current drinking (β = .08, ns). These results may be due to the relatively low frequency with which this college student population endorsed familial AUD.

Discussion

The primary finding from this study is that college students with greater current drinking rated alcohol pictures (predominantly advertisements) more positively than students with less current drinking. Our hypothesis that exposure to problem-drinking models would predict alcohol picture ratings and that personal alcohol use would mediate the relationship between exposure and alcohol picture valence ratings (see Figure 1) was not supported. Further, family history of AUD was not associated with valence ratings of alcohol pictures. Together, these results suggest that alcohol cue valence ratings of college students appear to be more experience dependent (i.e., learned through personal experiences with alcohol) than a result of vicarious learning (i.e., being exposed to drinking models in their families or friendships).

Exposure to problem-drinking models appeared related to personal heavy drinking, but was mostly accounted for by individuals endorsing regular exposure to non-familial, non-“friend” problem-drinkers. We had hypothesized that college students would be more likely to emulate peer behaviors, including problem drinking. However, results indicate that increased exposure to peer problem-drinking models did not correlate with personal alcohol use in this college sample. It is possible that heavy drinking individuals may have been less likely to identify their own friends’ drinking as problematic, thus obscuring any relationship between heavy drinking and peer problem drinking. In contrast, some of these heavier drinkers identified individuals such as dormitory neighbors and acquaintances as problem-drinkers.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. This study was conducted with a college sample, and it would be helpful to replicate findings with non-college young adults and younger adolescents. Although 20% of our sample reported drinking 100 or more drinks per month, we did not evaluate alcohol abuse and dependence criteria. A diagnosis might better summarize the alcohol involvement of some participants and could clarify the relationship found between drinking and valence ratings of cues. Furthermore, for investigating the effects of exposure to problem-drinking models, we specifically asked participants to report exposure to individuals who, in their opinion, drank too much alcohol or had problems related to their alcohol use. Perhaps more objective reports would have resulted from asking participants to report on exposure to individuals who drink regularly (i.e., at least once per week) or heavily (e.g., ≥ 4–5 drinks per occasion).

In summary, our study suggests that recent (i.e., past 3 months) personal alcohol use of college students, rather than common risk factors for alcohol dependence, can predict the experience of pleasantness while viewing a visual alcohol cue. Of clinical importance, this suggests that more positive affective experiences of stimuli such as alcohol advertisements may lead to an intensification of alcohol use, which in turn may reinforce positive affective responses to cues, creating a cycle that maintains heavy drinking. As alcohol advertisement expenditures predict alcohol consumption and escalation (Snyder et al., 2006), heavy drinking youths may be vulnerable to alcohol cues (Tapert et al., 2003), increasing alcohol use and related disorders. We encourage the use of the here introduced alcohol cue rating task as an indicator of risk for heavy alcohol involvement; results could be of great utility for the purpose of identifying individuals with greater need for prompt alcohol treatment interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kevin Cummins for statistical consultation, and Jennifer Escalante, Lain Lain Tan, Alina Anuccavech, Yoojin Kim, Shadi Sedijhzadeh and Andria Norman for assistance with data checking.

This research was supported by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants R01 AA13419 (Tapert), a minority supplement award to R01 AA013419-02S1 (Pulido), and F31 AA016423 (Pulido).

References

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin CK, Neuendorf K, McDermott S. The role of alcohol advertising in excessive and hazardous drinking. Journal of Drug Education. 1983;13:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice: Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman M, Cloninger R, Sigvardsson S, von Knorring AL. The genetics of alcoholisms and related disorders. Journal Psychiatry Research. 1987;21:447–452. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(87)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohman M, Sigvardsson S, Cloninger CR. Maternal inheritance of alcohol abuse. Cross-fostering analysis of adopted women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:965–969. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780340017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bot SM, Engels RC, Knibbe RA, Meeus WH. Friend's drinking behaviour and adolescent alcohol consumption: the moderating role of friendship characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:929–947. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM, Tapert SF. Four-year outcomes from adolescent alcohol and drug treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:381–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Myers MG, Lippke L, Tapert SF, Stewart DG, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR): a measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tate SR, Vik PW, Haas AL, Aarons GA. Modeling of alcohol use mediates the effect of family history of alcoholism on adolescent alcohol expectancies. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:20–27. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Vik PW, Creamer VA. Characteristics of relapse following adolescent substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, C.-N. International affective pictures system: Digitized photographs. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP. The moderation of adolescent-to-peer similarity in tobacco and alcohol use by school levels of substance use. Child Development. 2003a;74:279–291. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP. The moderation of genetic and shared-environmental influences on adolescent drinking by levels of parental drinking. Journal on Studies on Alcohol. 2003b;64:182–194. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. Inheritance of alcohol abuse. Cross-fostering analysis of adopted men. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780330019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Reich T, Bohman M. Inheritance of risk to develop alcoholism. NIDA Research Monograph. 1986;66:86–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Stice E, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent alcohol use and peer alcohol use: a longitudinal random coefficients model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nurnberger J, Jr., Edenberg HJ, Goate A, Crowe R, Rice J, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Hesselbrock V, Foroud T. Suggestive linkage on chromosome 1 for a quantitative alcohol-related phenotype. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:1453–1460. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034037.10333.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Plunkett J, Hamlin D, Nurnberger J, Jr., Kuperman S, Schuckit M, Hesselbrock V, Edenberg H, Bierut L. Association analyses of the serotonin transporter gene with lifetime depression and alcohol dependence in the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) sample. Psychiatr Genet. 2007;17:35–38. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e328011188b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Ruela A. Mediators and moderators of young adults' drinking. Addiction. 1994;89:63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW. Alcoholism and heredity. A review and hypothesis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1979;36:57–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780010063006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Trajectories of concurrent substance use disorders: a developmental, typological approach to comorbidity. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:902–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Davis CG, Kessler RC. The familial aggregation of common psychiatric and substance use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: a family history study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:541–548. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Instruction manual and affective ratings, The Center for Research in Psychophysiology. University of Florida; 1999. International affective picture system (IAPS) [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar PJ. Alcohol use in the year before marriage: alcohol expectancies and peer drinking as proximal influences on husband and wife alcohol involvement. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1666–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris BJ, Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Familial and "on-the-street" risk factors associated with alcohol use among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara MM, Sprinkle SD, Ricci NA. Beck Depression Inventory--II: College population study. Psychological Reports. 1998;82:1395–1401. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3c.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen T, Knibbe R, de Vries H. Social influences on young adults' alcohol consumption: norms, modeling, pressure, socializing, and conformity. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Barnes GM, Dintcheff BA, Farrell MP, Uhteg L. Parental and peer influences on the onset of heavier drinking among adolescents. Journal on Studies on Alcohol. 1998;v59:311–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Genetics and the risk for alcoholism. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 1985;254:2614–2617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunk DH. Peer models and children's behavioral change. Review of Educational Research. 1987;57:149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LB, Milici FF, Slater M, Sun H, Strizhakova Y. Effects of alcohol advertising exposure on drinking among youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:18–24. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg SF, Mudd SA, Blow FC, Hill EM. Evaluating measures of family history of alcoholism: density versus dichotomy. Addiction. 1998;93:1511–1520. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931015117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition in a sample of college students. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;19:187–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WG, Breiner MJ, Curtin JJ, Lang AR. Assessment of substance cue reactivity: advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:148–159. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swadi H. Individual risk factors for adolescent substance use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;55:209–224. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th Edition. Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Cheung EH, Brown GG, Frank LR, Paulus MP, Schweinsburg AD, Meloy MJ, Brown SA. Neural response to alcohol stimuli in adolescents with alcohol use disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:727–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman AD, Orenstein A. Why some children of alcoholics become alcoholics: emulation of the drinker. Adolescence. 1994;v29:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Johnson ML, Horn SM, Carr LG, Smith TL, Schuckit MA. Evaluation of the self-rating of the effects of alcohol form in Asian Americans with aldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphisms. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:784–789. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Perez JE, Ramel W. Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) in a student sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:545–551. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<545::aid-jclp7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. The association between parental alcohol-related behaviors and children's drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]