Abstract

Recent scholarship concerning low rates of marriage among low-income mothers emphasizes generalized gender distrust as a major impediment in forming sustainable intimate unions. Guided by symbolic interaction theory and longitudinal ethnographic data on 256 low-income mothers from the Three-City Study, we argue that generalized gender distrust may not be as influential in shaping mothers’ unions as some researchers suggest. Grounded theory analysis revealed that 96% of the mothers voiced a general distrust of men, yet that distrust did not deter them from involvement in intimate unions. Rather, the pivotal ways mothers enacted trust in their partners were demonstrated by 4 emergent forms of interpersonal trust that we labeled as suspended, compartmentalized, misplaced, and integrated. Implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: ethnography, generalized gender distrust, interpersonal trust, low-income mothers, marriage

It is now a popular premise that the decline of marriage among low-income populations reflects, in part, a deep, mutual lack of trust between women and men (Carlson, McLanahan, & England 2004; Edin, England, & Linnenberg, 2003; Wilson 1996). Although the notion of generalized gender distrust among the poor is not new (Hannerz, 1969; Rainwater, 1970), it has become increasingly prominent in recent scholarship. In their qualitative study of motherhood and marriage in low-income Philadelphia and New Jersey neighborhoods, Edin and Kefalas (2005, p. 126) wrote, “Mistrust seems to permeate the very air of these neighborhoods.” They argue that mistrust is particularly pernicious with respect to marriage: “Becoming comfortable with the idea of marriage is about trust - - the astonishing lack of it in most couple relationships, and the profound need for it in order to sustain a marriage.” Survey researchers also have reported evidence of the impact of gender distrust on intimate union formation (Raley & Sweeney, 2007). For example, in the Fragile Families Study, young unmarried women who had just given birth were significantly less likely to marry the fathers of their children over the next year if they responded affirmatively to statements that “men cannot be trusted to be faithful” and “in a dating relationship, a man is largely out to take advantage of a woman.” Mothers’ beliefs about distrust, the authors wrote, “are a strong deterrent to coresidential unions, particularly marriage” (Carlson et al, 2004, p. 251).

Yet despite low-income women’s voiced distrust of men, most continue to look for partners and to enter into cohabiting relationships (Lincoln, Taylor, & Jackson, 2008; Manning & Smock, 2005). Indeed, notwithstanding their distrust, some women move partners into their homes soon after meeting them. They may even have a series of rapidly evolving cohabiting relationships (see Lichter & Qian, 2008). The contradiction between women’s reported high levels of gender distrust and the prevalence of these kinds of intimate unions raises the following questions: If generalized gender distrust is as influential in the decline of marriage as several recent studies have suggested, why do so many women who declare their distrust of men enter into so many relationships, many with the hope of forming a sustainable marriage? Why doesn’t the pervasive sense of distrust lead more women to delay rapidly paced cohabiting relationships, for example, until they have cautiously accumulated evidence of a partner’s trustworthiness? In spite of harboring general gender distrust attitudes, do women create distinct forms of interpersonal trust that facilitate their entrée to or sustained presence in cohabiting, marital, or other forms of intimate unions? The key to answering these questions, we argue, lies in symbolic interaction perspectives on attitudes and behaviors and in longitudinal in-depth ethnographic data that chronicle, over time and in context, what women say and what they do in placing trust in their romantic partners.

According to symbolic interaction theory, human action (e.g., entering a cohabiting relationship) is not endemically a response to general attitudes (e.g., generalized gender distrust). Rather, actors put together lines of action (e.g., developing a form of interpersonal trust) based on their consideration of factors particular to situations. Blumer (1955, p. 64) pointed out that to fully understand human actions, one must “get inside individuals’ frameworks of operation,” identifying how they distinguish situational dimensions that are important to their actions and how they piece those dimensions together in deciding how to act, in this case, deciding how to trust romantic partners (also see Mills, 1940). In this line of reasoning, general attitudes provide little insight on the courses of action individuals choose to take. Knowledge of the situational processes that influence social acts, according to Blumer (1955, p. 63) is “of far greater predictive value than is any amount of knowledge about general attitudes.” Moreover, a reliance on general attitudes as bellwethers of human actions underscores a problematic tendency to assume that what people say is an accurate predictor of what they will actually do (see Deutscher 1966; Schuman & Johnson, 1976). While a general attitude may have some bearing on the actor’s decision to behave in one way or another, it represents, as Blumer (1955, p. 63) cautioned, “merely an element that enters into the developing acts - - no more than an initial bid for a possible line of action.”

In this article, we advocate taking a closer look at the specific forms of interpersonal trust that women demonstrate in their actual relationships with romantic partners. We assert that while mothers may harbor general attitudes about distrusting men, they seek, build, and maintain intimate unions by investing other forms of trust in their partners within the situations in which they find themselves. Low-income mothers, like any other category of actors entering social relationships, place trust in their potential partners based on a range of both generic and situationally specific conditions including economic uncertainty, recognized (and unrecognized) emotional and financial needs; and histories of physical or sexual abuse (Burton & Tucker, 2009; Huston & Melz, 2004; Josephson, 2002). Given the challenging and often variable conditions in which many low-income mothers find themselves, we expect mothers to exhibit a variety of trust-building and trust-placing approaches toward their romantic partners. Such approaches would arguably range along a continuum from placing full trust in a potential partner, to building limited amounts of situationally specific trust or, perhaps, putting almost no trust in the partners in question. Whatever the case, the interpersonal trust that develops in the course of attempting and maintaining an intimate relationship is an empirical matter - - something to be investigated rather than assumed.

Our principal objectives are to identify and to describe forms of situated interpersonal trust as they unfold in the romantic lives of low-income mothers. To achieve these objectives requires an analysis of longitudinal in-depth ethnographic data about mothers’ personal circumstances, and observations of mothers’ words about and actions when placing trust in their romantic partners. We use ethnographic data from the Welfare, Children, and Families: A Three-City Study (hereafter, the Three-City Study) to investigate the role of trust in mothers’ intimate unions and we employ grounded theory analysis to identify the forms and features of that trust. As Blumer (1955) suggested, our analysis ascertains the situational pieces that mothers put together in placing trust in their partners. Four emergent forms of trust that we labeled as suspended, compartmentalized, misplaced, and integrated were identified in the analysis and we present them as a typology. The conceptual and methodological pathways to discovering these forms, and the descriptions of their influence in mothers maintaining and serially seeking romantic unions, are detailed in the discussions that follow.

CONCEPTUALIZAING INTERPERSONAL TRUST IN ROMANTIC UNIONS

What situationally based forms of interpersonal trust do low-income mothers enact in their romantic unions? Our efforts to answer this question involved moving back and forth between the theoretical literature on interpersonal trust in romantic relationships and grounded theory analysis of the Three-City Study ethnographic data to determine how mothers do trust in their intimate relationships. Charmaz (2006) described this process as building a dialogue between extant theory and ethnographic data in the analysis process rather than allowing the process to be driven by either a deductive or by an inductive grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; LaRossa, 2005; Strauss, 1987). We saw this iterative process as an appropriate and necessary strategy for investigating patterns of generalized gender distrust and interpersonal trust among the Three-City Study’s ethnography participants, in large part, because their life situations were often quite complicated and paradoxical. Efforts to identify, understand, describe, and interpret mothers’ trusting behaviors required more conceptual guidance than a purely inductive grounded theory analysis of the data would render, or a solely deductive approach to generating hypotheses about trust from existing theories would yield.

Models of Interpersonal Trust

Interpersonal trust refers to one’s belief in the “benevolence, honesty, predictability, and dependability of a significant other’s words and behaviors towards the person making the judgment” (Larzelere & Huston, 1980, p. 596). Most of the models of interpersonal trust derive from studies of dating and marriage patterns among White, well-educated, financially stable couples and/or college students and arguably are considered to reflect normative patterns of how intimate partners build trust (Couch & Jones, 1997; Rotter, 1971). In one of the most influential models (Rempel, Holmes, & Zanna, 1985), trust is seen as something people acquire over time in well defined, increasingly intensive stages, as if they were walking up a staircase to a predetermined end - - usually, a marriage. According to these authors, stage one is the attainment of “predictability,” the judgment that the partner’s behavior is consistent and stable enough for that partner to be considered trustworthy. This stage is followed by “dependability,” the judgment that the partner is reliable and honest. Finally, the partners achieve “faith”- - the ability to trust each other beyond available evidence.

We questioned the applicability of these stages as we investigated interpersonal trust among low-income women. To be sure, some low-income women do have long-term stable trusting relationships with their partners (Marks et al, 2008). And, the development of trust in these relationships most likely proceeds along the lines described by Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna (1985), although this premise has not been empirically substantiated in low-income or racial and ethnic minority populations. Nonetheless, all too often, the lives of impoverished women are steeped in uncertainty and its corollary risks, perhaps rendering the stage oriented ideal of interpersonal trust more difficult to achieve (Burton & Tucker, 2009; Wood, 2001). For example, individuals with more or less stable sources of income can formulate strategic plans for their lives with a fair degree of confidence that those plans will come to fruition. Women who benefit from stability may be more likely to build trust in romantic partners in well-paced sequential stages, such as those described by Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna (1985). However, for some individuals living in poverty, it is difficult to strategize about life in predictable ways when you have little control over the forces that determine the viability of your plans. When instability tends to be the rule in life, rather than the exception, women may pursue shortcuts to trust that skip gathering reliable evidence about partners’ predictability and dependability and, rather, engage in relationships that are characterized by minimal expectations of their partners. In addition, given the limited pool of partners who have the personal and economic resources necessary for a long-term relationship, women (and men) may allow themselves to start relationships that have relatively limited promise for sustainability. But, they also may protect themselves from being exploited by limiting the amount of trust they place in their partners. Under these circumstances, a couple’s degree of trust may not progress beyond initial modest levels, never reaching the stage of faith.

Furthermore, there is an association between poverty and domestic violence and sexual abuse that can create difficulties for women in developing trust. Although both physical and sexual abuse occur in all segments of society, both are reported to occur at notably higher rates in low-income populations and with more devastating effects (Leone, Johnson, Cohan, & Lloyd, 2004). An extensive body of research suggested that experiencing domestic violence or having been sexually abused can have profound long-term consequences on women’s mental health that can lead to a diminished capacity for intimate partner trust and to a greater likelihood of making errors in judgment in placing trust in someone (Macmillan, 2001). For instance, women who suffer from untreated trauma related to abuse can manufacture romantic trust that rests on untenable fantasies and illusions. These women frequently embellish a less than benevolent partner’s virtues, minimize that partner’s threatening behaviors, and place trust in that partner despite witnessing behaviors that suggest that extreme caution is warranted.

Toward an Emergent Typology of Interpersonal Trust

As our grounded theory analysis progressed, two axes of variation in trust emerged. These two dimensions are discussed in the sociological literature on trust and social action. The first is the extent to which people gather information about their partners. In their discussion of trust as social action, Lewis and Weigert (1985) included a person’s ability to discriminate and gather evidence about whether a potential partner is trustworthy as one of the key components (also see Hardin, 2002). We took from this perspective the importance of paying attention to the extent to which a woman gathers evidence about the trustworthiness of her partner. Those who gather limited evidence may be taking a transactional orientation, which implies a limited partnership with men focused on meeting short term specific needs, such as companionship, sexual relations, protection, or material support (Youm & Paik, 2004; Zelizer, 2000). In contrast, women who gather substantial evidence may be taking a relational orientation in which they seek long term complex relationships with mutual commitment (van de Rijt & Buskens, 2006). In the latter situation, women seek to establish whether their partner is worthy of the trust that would be required for them to invest emotionally in the relationship.

The second dimension is the degree of dependence on a partner (Huston & Burgess, 1979; Rusbult, Wieselquist, Foster, & Witcher, 1999). Interdependence theory identified two ways in which dependence is relevant: (a) the level of dependence, which is characterized by the “degree to which an individual relies uniquely on a relationship for attaining a particular outcome;” and, (b) the mutuality of dependence, which concerns “the degree to which two individuals are similarly dependent on each other for attaining a good outcome” (Drigotas, Rusbult, & Verette, 1999, p. 390; Kelley & Thibaut, 1979). These levels of dependence can be applied to an understanding of trust behaviors among low-income mothers in the following ways: If a young poor mother’s needs for emotional support are chronically unmet by her support network, she may show a higher level of dependence on her partner to fulfill those needs. Her dependence on her partner can create one-sided, high stakes risks in trusting him, particularly if the partner is not comparably dependent on her. In this instance, trust can be quickly fabricated by the mother, but that trust can be unrealistic and short-lived. In contrast, when trust is mutually dependent, the mother and her partner equally rely on getting their emotional needs met in the relationship. Huston and Burgess (1979) argued that trust which is based on the partners’ mutual discovery that each provides the other with healthy rewards that cannot be obtained elsewhere is situated on more stable ground and has the best chance of being sustained in the relationship over time.

METHOD

To investigate the role of trust in low-income mothers’ intimate unions we used ethnographic data on economically disadvantaged families who participated in the Three-City Study. This study was a longitudinal, multisite, multimethod project designed to examine the impact of welfare reform on the lives of low-income African American, Latino, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White families and their young children (see Winston et al., 1999). Study participants resided in poor neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio. In addition to longitudinal surveys of a random sample comprising 2,402 families, and an embedded developmental study of 700 families, the Three-City Study included an ethnography of 256 families and their children. These families were not in the survey sample but resided in the same neighborhoods as survey respondents.

Sample Description

Families were recruited into the ethnography between June 1999 and December 2000. Recruitment sites included formal childcare settings (e.g., Head Start), the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program, neighborhood community centers, local welfare offices, churches, and other public assistance agencies. Of the 256 families who participated in the ethnography, 212 families were selected if they included a child age 2 to 4 to ensure sample comparability with the survey and embedded developmental samples. To inform our understanding of how welfare reform was affecting families with disabilities, the other 44 ethnography families were recruited specifically because they had a child age 0 to 8 years with a moderate or severe disability. At the time of enrollment in the ethnography, all families had household incomes at or below 200% of the federal poverty line.

Table 1 reports demographic characteristics of the mothers in the ethnography sample. The majority of mothers (42%) were of Latino or Hispanic ethnicity with the largest groups being Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans, in that order. Over half of the mothers (58%) were age 29 or younger when they enrolled in the study and a majority (57%) had a high school diploma, General Equivalency Diploma (GED), or had attended trade school or college. Forty-nine percent of the mothers were receiving Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) when they entered the study; one-third of these were also working. The 256 mothers identified a total of 685 children in their households, with 53% of the children being under 4 years of age.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics: Three-City Study Ethnography (N=256)

| Characteristic | N | %a |

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

| Boston | 71 | 28 |

| Chicago | 95 | 37 |

| San Antonio | 90 | 35 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 98 | 38 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 108 | 42 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 50 | 20 |

| Ages of Primary Caregivers | ||

| 15 – 19 | 21 | 8 |

| 20 – 24 | 67 | 26 |

| 25 – 29 | 62 | 24 |

| 30 – 34 | 36 | 14 |

| 35 – 39 | 35 | 14 |

| 40+ | 35 | 14 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 110 | 43 |

| Completed high school or GED | 67 | 26 |

| College or trade school | 79 | 31 |

| TANF / Work Status | ||

| TANF / Working | 40 | 16 |

| TANF / Not Working | 85 | 33 |

| Non-TANF / Working | 64 | 25 |

| Non-TANF / Not Working | 67 | 26 |

| Number of Children Primary Caregiver Is Responsible For |

||

| 1 Child | 64 | 25 |

| 2 Children | 70 | 27 |

| 3 Children | 63 | 25 |

| ≥4 Children | 59 | 23 |

| Children’s Ages | ||

| < 2 | 190 | 28 |

| 2 – 4 | 174 | 25 |

| 5 – 9 | 205 | 30 |

| 10 – 14 | 88 | 13 |

| 15 – 18 | 28 | 4 |

| Total | 685 | |

| Intimate Union Patternsb | ||

| Sustained Unions | 112 | 45 |

| Transient Unions | 93 | 37 |

| Abated Unions | 46 | 18 |

| History of Physical and Sexual Abusec |

||

| None | 81 | 35 |

| Sexual Abuse | 6 | 3 |

| Physical Abuse | 59 | 26 |

| Sexual and Physical Abuse | 82 | 36 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

There are missing data for five cases in the Intimate Unions category.

There are incomplete data for 28 cases in the History of Physical and Sexual Abuse category.

The majority of mothers (56%) indicated that they were neither married nor cohabiting at the outset of the study, but longitudinal interviews and observations of the sample revealed that more respondents were in marital or cohabiting relationships than said they were, and some were also serially moving from one intimate union to another. Thus, we classified mothers’ intimate unions in ways that captured the fluidity in relationships that many of their histories showed. Mothers demonstrated 1 of 3 union history categories - - sustained, transitory, or abated unions (see Cherlin, Burton, Hurt, & Purvin, 2004). Forty-five percent of the mothers were categorized as having sustained unions, meaning that, as adults, they had been in 1 or 2 marital or cohabiting unions lasting 3 or more years. Thirty-seven percent of the mothers had transitory unions. Transitory unions involved mothers being involved in sequential short-term partnerships with different men, or mothers having long-term involvements with men that cycled between living together and breaking up (usually in 3 to 6 month intervals) and living with other men during the break-up periods. Eighteen percent of the mothers were classified as having abated unions. Mothers in this category indicated that they were not in a serious union during the course of the study and were not married or had not cohabited for at least one year prior to enrolling in the study. These women told ethnographers that they were not interested in having romantic relationships, although they mentioned having casual emotionally-detached short-term liaisons or hook-ups with men.

Given the well documented link between poverty, physical and sexual abuse, and interpersonal trust, we also highlight the prevalence of these experiences in mothers’ lives in Table 1. Sexual abuse included mothers’ reports of rape, molestation, parentally enforced child prostitution, and witnessing incest acts (e.g., watching one’s father molest one’s sister on a nightly basis for a decade). Physical abuse comprised physical beatings, attacks with weapons, and witnessing consistent physical violence among parents, partners, and children. We did not include physical abuse incidents of short duration nor of questionable intensity such as watching one’s mother’s boyfriend slap her once. Thirty-six percent of the mothers disclosed that they had been sexually and physically abused; 3% revealed that they had only been sexually abused (primarily in childhood), and 26% said they had only been physically abused (primarily in domestic violence situations as adults). In 35% of the cases, mothers reported that they had never been sexually or physically abused.

Ethnographic Methodology

To gather and to analyze ethnographic data on the mothers and their families, a method of structured discovery was devised to systematize and to coordinate the efforts of the Three-City Study ethnography team [for a detailed description of the research design of the ethnography see Winston et al., 1999]. An integrated and transparent process was developed for collecting, handling, and analyzing data that involved consistent input from over 215 ethnographers, qualitative data analysts, and research scientists who worked on the project over the course of 6 years. Interviews with and observations of the respondents focused on specific topics but allowed flexibility to capture unexpected findings and relationships among variables. The interviews covered a wide variety of topics including intimate relationships, health and access to health care services, family economies, support networks, and neighborhood environments. Ethnographers also engaged in participant observation with respondents that involved attending family functions and outings, witnessing relationship milestones (e.g., couple’s decision to cohabit) between mothers and their partners, accompanying mothers and their children to the welfare office, hospital, daycare, or workplace, and noting both context and interactions in each situation. In 92% of the cases, an ethnographer was racially matched with a respondent and remained that family’s ethnographer for the duration of the study. In most cases, interviews and participant observations were conducted in English with the exception of 34 families who preferred Spanish. Ethnographers met with each family once or twice per month for 12 – 18 months then every 6 months thereafter through 2003. Respondents were compensated with grocery or department store vouchers for each interview or participant observation.

Data Sources, Coding, and Analysis

The ethnography generated multiple sources of data that we used to examine trust behaviors and intimate unions within the sample. The primary data sources were ethnographers’ fieldnotes about their interviews and participant observations with families and transcripts of all their tape-recorded interviews. In addition, we consulted transcripts of principal investigators’ group and individual discussions with ethnographers and qualitative data analysts about the families. [During the data collection process, we held monthly cross site Thought Provoking Questions (TPQ) conference calls with ethnographers and qualitative data analysts. The purpose of these calls was to discuss emergent themes in ethnographers’ ongoing field observations and in the data analysts’ synthesis of the ethnographers’ fieldnotes and transcribed interviews.] All sources of data were coded collaboratively [according to a general thematic coding scheme developed by the principal investigators] by ethnographers and qualitative data analysts for entry into a qualitative data management (QDM) software application and then summarized into detailed case profiles about each family.

Three phases of data coding were conducted in this analysis. The first phase involved open coding of fieldnotes, interview transcripts, family profiles, and TPQ transcripts. We began by using the general coding scheme developed by the project’s principal investigators to pinpoint the contextual and situational aspects of mothers’ lives. These codes included, but were not limited to, a focus on mothers’ romantic relationship transitions, histories of physical and sexual abuse, health crises, educational accomplishments, and self-improvement behaviors. We used these codes in tandem with open coding to identify general indicators, concepts, and themes concerning mothers’ words and behaviors about generalized and interpersonal trust (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; LaRossa, 2005). For example, emergent indicators of generalized gender distrust comprised mothers’ unsolicited comments about distrusting men. These comments often emerged in mothers’ recounting something they had seen on television, read in a magazine, or heard when sharing gossip about recent romantic relationship events in the lives of their families and friends. Statements made by mothers such as: “Dogs, dogs, dogs, dogs, all men are dogs;” “Men are lyin’, cheatin’ bastards . . . every last one of them;” and, “Huh, you can’t trust not a one of them” were coded as indicators of mothers’ generalized gender distrust. Mothers’ comments such as, “Oh, you know, he has pretty eyes and looks at me like he loves me, so I trust him;” and, “I trust him for one thing and only one thing. I don’t want to trust him for more than that,” were coded as a general indicator of situated interpersonal trust.

Another exemplar of open coding involved discerning indicators of paradoxical trust behaviors. Mothers frequently offered perspectives about their trust attitudes and behaviors that were inconsistent with what ethnographers observed about their choices and actions in intimate unions. For instance, Nona, a 23-year-old mother of three girls and a survivor of childhood sexual abuse talked about “what a dog her neighbor’s boyfriend was . . . always lying, cheating, and beating . . . but didn’t seem to be able to draw the connection in her comments to the fact that her own live-in partner was doing the same thing to her.” We used mothers’ patterns of paradoxical trust behaviors as an indicator of participants’ self- awareness concerning how they placed trust in their own partners as compared to the trust behaviors of those they criticized.

We then proceeded to the second phase of analysis, axial coding. In this phase we conducted more intensive analyses of generalized gender distrust and situated trust. We determined the conditions, phases, and personal strategies that characterized mothers’ trust behaviors, drawing linkages among emergent variables and processes (see Glaser, 1978 and LaRossa, 2005). The axial coding rendered a non-distinct, general form of gender distrust that was consistent across all cases and was synonymous with commonly shared public attitudes about women and men not trusting each other in general. Four forms of situated interpersonal trust also emerged in these analyses. We labeled the emergent forms as suspended, misplaced, compartmentalized, and integrated and present them as an interpersonal trust typology in the results section of the article.

The third phase, selective coding, comprised what LaRossa, (2005, p. 850) described as “deciding on the main story underlying the analysis.” The most relevant story to emerge in the data concerned mothers’ use of particular forms of interpersonal trust and how those forms were shaped by mothers’ life situations. These forms appeared to trump the impact of generalized gender distrust on mothers’ intimate union behaviors. Below, we report findings concerning mothers’ patterns of generalized gender distrust and then we describe how mothers demonstrated certain types of interpersonal trust in their romantic relationships. We also summarize findings about the ways particular life situations (e.g., domestic violence and sexual abuse) influenced mothers’ trust behaviors. We use representative exemplar cases to illustrate the parameters of trust as well as the relationship among trust and other variables that emerged in the data. Where specific case examples are used, respondents have been assigned pseudonyms.

RESULTS

Generalized Gender Distrust

Identifying mothers’ patterns of generalized distrust was a fairly straightforward process with clearly delineated trends emerging during the open coding of the data and subsequently being confirmed during the axial coding phase. An overwhelming majority of the mothers (96%) indicated that, in general, they did not trust men. Each mother made general statements about distrusting (rather than trusting) men an average of 12 times over the course of the study. Statements included: “Don’t trust a man any farther than you can throw him;” “They are dirty;” or “En los hombres no se puede confiar [you can never trust a man].” Nonetheless, in the context of making these statements, mothers did not shy away from intimate unions. Despite their avidly voiced general distrust of men, 82% of the mothers were in sustained marital or cohabiting unions or in a series of transitory unions with men. Mothers who declared themselves to be off the marriage market also occasionally had short-term, hook-up-like relationships with men. In essence, rather than relying solely on their general attitudes about gender distrust to define their decisions about intimate unions, mothers developed and engaged in situated forms of interpersonal trust that facilitated their entrée to and presence in romantic unions.

Situated Interpersonal Trust

How Mothers Revealed Interpersonal Trust Attitudes and Behaviors

Identifying relevant dimensions of situated trust in the data was a complex process, in large part, because mothers’ differentially revealed how they placed trust in their partners. Approximately 6 in 10 of the mothers were direct and consistent in their words and actions about placing trust in their romantic partners. In about 4 in 10 cases, however, the dimensions of interpersonal trust were observed only after prolonged interactions between the ethnographers and the respondents. Essentially, 42% of the mothers exhibited less than straightforward interpretations and behaviors about their intimate relationships and trust at the outset of the study.

Let us consider the case of Guadalupe, a 27-year-old Mexican American mother of 3 children. Her initial words and actions around trust and intimate unions were framed by the cultural practice, el que dirán, which resulted in lengthy, sometimes confusing periods of uncovering the true nature of her relationship with her husband. El que dirán is a common cultural practice among Hispanics and Latinos and literally translates as “what will they say,” and implicitly “what will they think” (Sanchez Acona, 1964). It is a perspective that integrates Mead’s (1934) notion of the generalized other and Goffman’s (1959) presentation of self in everyday life and is concerned with how others (e.g., community members) view one’s behaviors. For some mothers, el que dirán was a powerful force in shaping their words and behaviors toward impression management. Guadalupe had strong ties to both her family of origin and the wider Hispanic community and as demonstrated in her words and behaviors, was constantly preoccupied with what people thought about her and, by association, how her actions influenced what others thought about her family.

Guadalupe’s mother, Margarita, enforced the principles of el que dirán in Guadalupe’s responses to the ethnographer’s queries, particularly around discussions of Guadalupe’s husband and her marriage. Margarita was present at several of Guadalupe’s interviews and chastened Guadalupe, through her presence, to paint a very positive picture of her marriage. “She rolled her eyes and made guttural sounds whenever Guadalupe suggested that anything in her life was less than perfect.” It was not until the ethnographer had the opportunity to meet with Guadalupe alone and away from her home, nearly 15 months into the study, that Guadalupe shared that her husband was abusive and that she trusted him “only as a provider . . . he is a cheater . . . he has many women.” Shortly after Guadalupe’s disclosure, the ethnographer received a call from Margarita telling her not to visit Guadalupe again as her presence was causing trouble in her daughter’s marriage and that she did not want any of the neighbors or her relatives to know about those troubles.

Forms and Features of Situated Interpersonal Trust

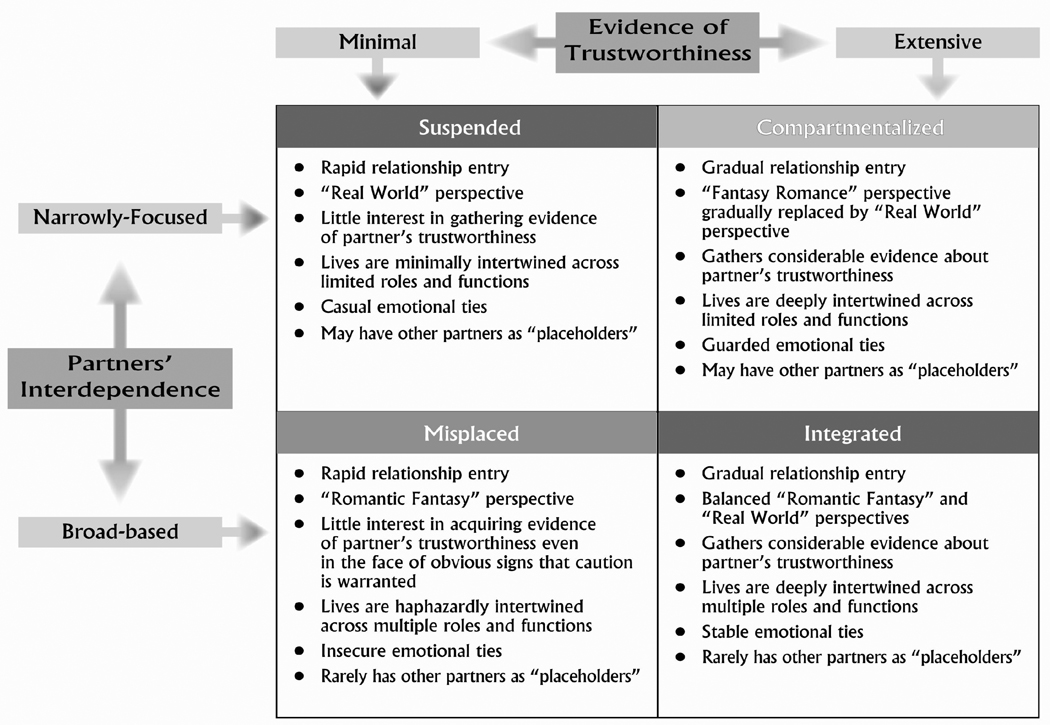

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual categories of situated interpersonal trust derived from the grounded theory analysis. Four forms of trust - - suspended, misplaced, compartmentalized, and integrated - - emerged in the analysis and we present them as a typology of interpersonal trust. The defining features of interpersonal trust were: (a) mothers’ attention to and reliance on evidence of partners’ trustworthiness (ranging from minimal to extensive), and (b) partners’ interdependence, which is the degree to which mothers’ and their partners’ (based on mothers’ perceptions and the ethnographers’ observations of mothers and their partners) lives were intertwined. Interdependence also reflected the extent to which mothers and their partners had relational or transactional orientations in their dealings with one another; relied on each other for emotional and material support; and had circumscribed roles and functions in their relationships. Other emergent parameters of trust included: (a) the pace at which mothers entered relationships; (b) whether mothers had “real world” or “romantic fantasy” perspectives about their unions; (c) the level of emotional connectedness in mothers’ romantic relationships; and, (d) whether mothers kept “placeholders” or other potential partners “on the side” when they were in a romantic union. We categorized mothers as exhibiting a certain type of trust based on whether they demonstrated at least 4 of the characteristics of that type, and whether that form of trust was the modal type of trust they used within and across most of their romantic unions (e.g., used one form of trust in 3 out of 5 cohabiting unions, or used one form of trust “most of the time” in a long-term marital union). Although mothers demonstrated several variants of interpersonal trust within and across their relationships, the majority (86%) had a penchant for using 1 type of trust more frequently than others because they tended to select partners with similar characteristics as they moved from one relationship to another.

Figure 1.

Forms and Features of Interpersonal Trust in Intimate Unions: An Emergent Typology

We categorized each mother as belonging to 1 of the interpersonal trust types, but not everyone fit perfectly into each category. There were gray areas regarding our interpretations of whether mothers demonstrated through their spoken words and in their behaviors the precise nature of their attitudes, expectations, and needs around trust. As you will see in the exemplar cases presented below, the lines of distinction between forms of trust were sometimes tenuous.

Suspended Trust

Suspended trust was observed among 26% of the mothers in the sample. These mothers, as did the vast majority of respondents, expressed a generalized distrust of men, but from time to time entered into arrangements with men that to the ethnographers and to respondents’ friends and family members appeared to be quasi-intimate partnerships. These quasi-partnerships began very quickly, with the man and the respondent having frequent clandestine meetings, or the man visiting the respondent’s home several times a week according to a schedule designated by the respondent. These interactions usually occurred after what one mother called, “a short getting-to-know-you hook-up.”

Mothers can be said to have suspended trust in their partners as evidenced by a number of indicators. First and foremost, mothers in this category devoted little attention to acquiring hard and fast evidence of their partners’ trustworthiness. The data suggested that suspended trusters generally had a transactional orientation, entering relationships with the interest of getting particular needs meet (e.g., rent, food for children) and usually under circumstances when a short term crisis (e.g., needing money to pay the rent) arose in their lives. As such, mothers who suspended trust were not initially concerned with whether their unions would survive beyond getting their current needs met and they saw no need to delve deeply into their partners’ personal histories. These mothers also did not engage in elaborate fantasies about their relationships. Rather, they voiced realistic appraisals about their partners’ capacities to meet their needs, often brashly speaking about their partners’ limitations and objectionable character traits. Trust in these situations appeared to be “hanging in the balance.”

Interdependence among partners with suspended trust was slight at best. Mothers and their partners had very limited and specific roles in each others’ lives and were very clear about expectations concerning those roles. Mothers created specific boundaries in these relationships: They did not try to deeply embed their partners in their social networks and they did not expose their own emotional vulnerabilities to them. Instead, mothers appeared to suspend judgments about trust knowing that the emotional risks of the arrangement were low and the duration limited. Overall, mothers who enacted suspended trust saw their trust behaviors as “not the real kind of trust.” In viewing trust and relationships in this way mothers retained governance over every aspect of their lives in these unions and suffered little to no distress when relationships ended. In fact, they often had other potential partners, from whom they were just as emotionally detached, waiting in the wings.

Angie, a 29-year-old White mother of 2 daughters, enacted suspended trust with most of her partners while adamantly declaring her mistrust of men. As a survivor of 5 years of domestic violence and panic disorders, she noted, “They are all no good, every last one of them.” Despite her strong distrust of men and formal declarations that she was “off the marriage market,” Angie sought brief intimate relationships from time to time and had a specific plan in doing so. She actively sought partners who could meet her short-term needs for purchasing things for her house, her children, and providing care for her elderly ailing parents. “I ain’t looking for that love shit,” she declared. “I need a man to help me for a minute, and he’s out of my house after that. You see, we got to have an understanding. I get what I need, he gets what he needs, and it’s a done deal. I don’t need to know nothin’ about how he gets what he gets [e.g., acquiring financial resources]. I don’t want to know nothin’ that particular. I’m in control. I run this shit up in here.”

Being in control was a key issue for mothers who suspended trust, in large part because they were dealing with so many other dimensions of uncertainty in their lives, particularly around their economic vitality and family health concerns. Brenda, a 24-year-old African American mother of a young boy, for example, clearly articulated that she preferred relationships in which she had the “upper hand” and could put limits on the trust she extended to her partners. “I don’t give a good god damn about putting all myself into any relationship or expecting him to do it too. We straight when he knows just what I want and no more. No surprises . . . don’t want no surprises. I don’t care if he has other women either just as long as I know who they are and he keeps them out of my business. I know what to expect. That’s what works for me.”

Compartmentalized Trust

Twenty-six percent of the mothers demonstrated patterns of compartmentalized trust. These mothers shared some similarities with those who engaged in suspended trust behaviors. Like mothers who suspended trust, mothers who compartmentalized trust had relationships characterized by limited interdependence and transactional orientations. They relied on their partners for very specific things, such as taking care of their children, or in the case of some mothers who had emigrated from Central America, providing financial support for their family “back home.” These relationships were often very practical with little emotional base, meaning that when these relationships ended, there was minimal emotional indignation. As such, occasionally, mothers had other partners on the side primarily to meet their own emotional needs.

Mothers who placed compartmentalized trust in their partners differed from those who used suspended trust in that their relationships developed gradually, moving from romantic fantasies to realistic views of the complexities of romantic unions over an extended period of time. Compartmentalized trusters also tended to invest considerable effort in determining the trustworthiness of their partners, but only in specific domains (e.g., can the father provide care for the child). Mothers’ typically showed little interest in determining whether their partners were trustworthy across domains that were not critical to theirs or their children’s immediate needs.

Hortensia, now 28-years-old, is the mother of three sons. She migrated from Central America to the United States with her partner, and at that time, 2 children, when she was 21. Hortensia had lived with her husband since she was 14, moving in with him and his family eight months before they married. She left her natal home because of her abusive father. Hortensia shared a number of insights with her ethnographer about how she learned to trust men. She indicated that her grandmother warned her as a child that “men can only make a woman’s life miserable and that she should never trust any man.” Her grandmother’s cautionary tale, however, did not keep her from developing her own brand of interpersonal trust. Hortensia indicated that she trusted her partner, but only to provide financially for her children and to send money to support her family in Central America. She said, “Our relationship is not love, I do not trust him with my heart. I have someone else [a paramour in Central America] that I can trust with my heart. We [Hortensia and her husband] trust each other only for some things. It is like a business agreement and I can depend on him to do his job.”

Misplaced Trust

Twenty-three percent of the mothers exhibited patterns of misplaced trust. Mothers who misplaced trust in their partners put minimal value on gathering evidence about their partners’ abilities to be trusted and based their trust on “fantasy,” “hope,” and self-contrived, often inaccurate stories of their partners’ virtues. Mothers in this category typically misrepresented or explained away threatening information about their partners’ behaviors, even when there was some recognition of disturbing evidence about the partners by family members, friends, or the ethnographers. We surmised that some of these mothers were motivated to present inaccurate profiles of their partners to themselves and to others as a way to temporarily keep their relationships afloat.

Mothers who misplaced trust also tended to have a relational orientation and sought long-term relationships, frequently without success. They typically escalated a relationship to coresidential status soon after meeting a man even though their knowledge about him was incomplete. Lewis and Weigert (1985, p. 970) described this pattern as “overdrawing” one’s informational base, “by leaping beyond the expectations for the relationship that reason and experience alone would warrant.” Both parties in these relationships tended to have excessive needs: the woman, primarily emotional, and the male partner, material, most often housing. Interdependence within these unions ran high, but the relationships rarely lasted long and frequently were abusive. The nature of the relationships usually resulted in volatile breakups with mothers experiencing intense feelings of emotional betrayal. More importantly, these arrangements put children at significant risk for witnessing abuse or being abused by the mother’s partner. And, these mothers usually did not have another potential partner in the wings for the duration of these relationships.

There was very little variability among mothers who misplaced trust, such that Helena, a 42-year-old African American mother of eight children, exemplifies the characteristics of mothers in this category. Like most of the mothers who misplaced trust, Helena often mentioned that she did not trust men. Similar to some mothers, she also had relatively poor health and suffered from depression and anxiety that she attributed to being sexually abused as a child and not being able to find the “right man” as an adult.

Helena had a series of short-term cohabiting relationships since the age of 18 when she secured her own residence in the projects. By her own admission, she met potential partners fairly easily and fell in love quickly, inviting them to move in with her after knowing them for less than a month. She stated, “I am scared to live alone and I feel safe when a man is around. I know that he will learn to love me, because I give everything . . . a lot of love, mostly. My man right now, I give him a house to live in and a child to love. I believe he will do right by me. I trust him.”

Helena’s partners rarely provided her with any evidence that they were trustworthy. For example, her first child’s father stole money from her and gave her a sexually transmitted disease that he also shared with three other women he was simultaneously involved with. And, her most recent co-resident boyfriend frequently climbed out of their bedroom window at night to visit another woman down the hall. Yet, Helena continued to hope that their relationship would last. She said, “He ain’t going nowhere. We need each other.” Within 1 week of making that statement, Helena’s boyfriend moved in with the other woman. Shortly after he left, Helena became so depressed and anxious that she had to be hospitalized for 3 weeks. When asked what she would do if her boyfriend returned, she said, “I would marry him. He can come back. He can come back. I know he didn’t mean to hurt me. I know way down inside, I can trust him.”

Integrated Trust

Twenty-four percent of the mothers demonstrated patterns of integrated trust. Mothers who engaged in integrated trust behaviors tended to enter relationships gradually, placing high value on evidence of their partner’s ability to be trusted across multiple domains over time. Unlike those mothers who engaged in misplaced trust, these mothers described their relationships as balanced between reality and fantasy. They desired romance but they also understood the realities of what it took to make relationships work for the long haul.

The lives of the mothers who enacted integrated trust were deeply intertwined with those of their partners and represented a hybrid of relational and transactional orientations. Mothers depended on their partners for a broad range of needs including emotional, spiritual, financial, social, parental, and recreational support, and their partners likewise depended on them. For these couples, emotional ties tended to be deeply rooted and stable such that breakups involving violations of trust were emotionally capricious with mothers struggling for long periods of time to move from interdependence to independence. These mothers rarely had other potential partners on the side and if they moved on to another relationship after a break-up, their conversations with new partners were characterized by reminiscent statements about emotional connectedness to their former partners.

Shana is a 26-year-old African American mother of 2 children, wife to her husband of 4 years, and daughter, sister, and niece to a biological father, 2 stepfathers, 3 brothers, and 6 uncles, respectively. Shana talked about the men in her natal family as giving her “every reason in the world to never trust a man. They just ain’t right.” And surely, in the neighborhood she grew up in, “that’s all women ever preached about was, you can’t trust no man.” Despite Shana’s socialization for a general distrust of men, she recalled that she decided to pursue a relationship with her husband after “checking him out” for a year. “I watched how he handled his business and treated other peoples’ feelings, and if he did what he said he was going to do . . . and he did.” Shana and her husband were very mindful of each other’s needs and devoted special time in their days to tend to their relationship. She stated, “We trust each other very much. I don’t know what we would do without each other.”

While Shana’s circumstance was clearly one of integrated trust, we acknowledge that 5 of the respondent assignments we made to this category were questionable. Carmen’s relationship with Miguel, for example, appeared to be comparable to Shana’s, at least on the surface. Carmen, a 25-year-old Mexican American mother of 2 children, seemed to be devoted to her husband Miguel who was a “reliable provider and good husband and father.” The ethnographer reported for 2 years that Carmen and Miguel were a model couple who loved and trusted each other intently, and there was no information in the fieldnotes or transcripts that suggested otherwise. During the ethnographer’s last interview with Carmen, however, Carmen disclosed through a steady stream of tears that her entire relationship with Miguel was a lie and that she was with him only for the money: “He’s been cheating on me the whole time . . . since I first knew you. And I knew it and all I wanted was the money so that I could get a house and divorce him . . . I was just waiting and I could not tell you.” Given that we only had this one data point that suggested that Carmen placed compartmentalized trust in her partner, on the basis of what she told the ethnographer in the other interviews and the ethnographer’s own observations, we categorized her as an integrated truster. It is very likely that Carmen represents a hybrid of both types of trust and that her brand of trust lies somewhere between the integrated and compartmentalized categories in the typology.

Mothers’ Attributes and Interpersonal Trust

The number of children mothers had and their educational levels did not differentiate the types of interpersonal trust they placed in their partners. Moreover, we found that a mother’s age was not a good predictor of where she fit in the trust typology. One might logically assume that older mothers would have more extensive relationship histories and life experience than younger ones which would translate into them engaging in different types of trust behaviors. There was, however, considerable variability in the sample in that some younger mothers had more extensive relationship histories than older ones; and age was not necessarily a proxy for developmental maturity. Thus, interpersonal trust and its modal occurrence reflected the types of relationships (e.g., serial cohabitation) and partners a mother had experienced but it did not necessarily correspond to the developmental maturities that one would expect given that mother’s chronological age.

Furthermore, race and ethnicity mattered in the ways mothers’ revealed information about trust and put limitations on placing trust in a partner, but primarily for Mexican American mothers. Mexican American mothers’ concerns about how they appeared to others, via the cultural practice of el que dirán, and their affinity for limiting the transactional and relational boundaries of trust, situated over half of them in the compartmentalized trust category. We were the most tentative about assigning these mothers to this category as we suspected that their trust behaviors were more variable than demonstrated, but that the variability was muted by el que dirán.

Abuse and Interpersonal Trust

We did find high levels of physical and sexual abuse among mothers who engaged in suspended, misplaced, and compartmentalized trust behaviors but substantially lower levels of abuse among mothers who showed integrated trust (see Table 2). Seventy-five percent of the mothers who placed suspended trust in their partners and had a history of abuse were primarily physically abused as adults in previous intimate unions. They voiced strong desires to control and limit their trust of men. Angel, a 32-year-old Puerto Rican mother of 2 children said: “Nobody will ever hit me again like he did … I will never trust a man that way again. I will be the one in control.”

Table 2.

Percent History of Abuse (Physical and Sexual) by Forms of Interpersonal Trust: Three-City Study Ethnographya (N=228)

| Forms of Interpersonal Trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abuse History |

Suspended | Compartmentalized | Misplaced | Integrated |

| No | 25 | 37 | 13 | 69 |

| Yes | 75 | 63 | 87 | 31 |

| Total % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| N | 60 | 53 | 60 | 55 |

Total ethnography sample N=256 (28 cases were not included in this analysis because of insufficient data).

Sixty-three percent of the mothers who demonstrated compartmentalized trust behaviors also were victims of abuse. Over half of these mothers were Hispanic and, for a few, their beliefs and behaviors around trust and relationships were embedded in el que dirán and traditional notions of marriage and men’s and women’s family roles. These notions facilitated their tendencies to extend trust to their partners in specific domains and remain in long-term relationships regardless of the circumstances within the union (Gonzales-Lopez, 2005; Lloyd, 2006).

A notable 87% of the mothers who engaged in misplaced trust had extensive untreated histories of physical and sexual abuse

These mothers teetered between being anxious, fearful, and depressed, trusted men easily, and quickly moved from one relationship to another. Marilyn, a 45-year-old White mother of 4 children had a long history of being physically and sexually abused. She continually entered and exited relationships with men, letting them move into her household only days after meeting them. She often developed grand plans for what she would do in these relationships including, in one situation, “getting her new man to buy her a $300,000 condominium” although he was unemployed and had no savings. Most of the men that Marilyn invited into her home and the lives of her children abused her and/or her children. Marilyn, however, never seemed to figure out that misplacing trust in her partners put her and her children at considerable risk time and again.

Thirty-one percent of the mothers who enacted integrated trust in their partners also had a history of abuse, albeit at a comparatively lower level. This difference suggested that women who had not experienced abuse were better able to place trust in partners in ways that lead to lasting unions. Five of these mothers reported that they had received relationship counseling and therapy for anxiety, both of which helped them to work through problems in their relationships. Nine mothers used prayer as a way to deal with their abuse histories and build trusting relationships with their partners. Still, in 3 cases, mothers demonstrated signs of integrated trust, but appeared not to have dealt with their histories of abuse. These women evidenced marginal signs of self-awareness, and, debatably could have been placed in other categories of trust.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this article, we created a dialogue between extant theories and grounded theory analysis (Charmaz, 2006) to question a popular premise in the scholarly literature - - whether generalized gender distrust is a major impediment to the formation of sustainable intimate unions among low-income mothers. In doing so, we explored the relationship among generalized gender distrust, emergent forms of situated interpersonal trust, and low-income mothers’ romantic union behaviors. Consistent with Blumer’s (1955) theoretical propositions, results indicated that generalized gender distrust was not as influential in shaping low-income mothers’ unions as some researchers have argued. Mothers were not deterred by generalized gender distrust from serially seeking or maintaining intimate unions. Rather, the pivotal ways mothers enacted trust in their partners were demonstrated by 4 emergent forms of interpersonal trust that we labeled as suspended, compartmentalized, misplaced, and integrated.

On the basis of our research findings, we maintain that this study makes several important contributions to the literature. The first specifically concerns recent scholarship on gender distrust and marriage. Essentially, our ethnographic findings suggested that the emphasis on generalized gender distrust in current research on declines in marriage among low-income women misses the trees for the forest. Rather than focusing on the forest of broad based gender distrust, scholars would be better advised to note how the trees - - the types of situated trust women enact in particular relationships - - impact marriage, cohabitation, and other forms of intimate unions. In other words, to fully understand intimate unions among low-income women, researchers must move beyond primarily using general attitudes, like gender distrust, to explain trends in marriage and cohabitation and examine the more complex forms of trust that poor women construct and enact in relationships based on the situations in which they find themselves.

The second contribution is that we introduced new forms of interpersonal trust into the conceptual literature on trust and intimate unions - - forms that were derived from ethnographic research on a sample of low-income, racially/ethnically diverse women. Marks et al., (2008, p. 173) stated that: “Extant research has indicated that a lack of trust prevents marital formation and contributes to marital dissolution, but there is a paucity of research that offers insight regarding how trust is created and maintained across time. This is a conspicuous need in the knowledge base.” Our identification of suspended, compartmentalized, misplaced, and integrated trust begins to address this need while also giving voice to the experiences of low-income, racially/ethnically diverse women who have been sorely neglected in this line of research. Indeed, we acknowledge that our findings are not derived from data on a probability sample and that to some researchers this circumstance may raise questions about the generalizability of the results. Nonetheless, we contend that by identifying and describing the characteristics of mothers’ trust behaviors, we provide family researchers with useful conceptual knowledge and potential research questions that are relevant to current work in this area beyond studies of poor women.

For example, we learned that mothers who suspended trust usually had short term and transactionally oriented relationships and that these mothers were the most self-protective and matter-of-fact in how interpersonal trust was demonstrated in their words and behaviors. We believe that although specific needs related to poverty shaped the suspended trust behaviors of these mothers, there are aspects of suspended trust that may be relevant to couples’ cohabiting behaviors in other socioeconomic groups. Recent demographic findings have shown that regardless of socioeconomic status, American couples are increasingly sliding into serial cohabiting relationships with ambiguous intentions for marriage (Stanley, Rhoades, & Markman, 2006). These relationships, like those of the suspended trusters, are characterized by quick entreés, partners gathering little evidence about trustworthiness, limited interdependence, and an emphasis on partners meeting specific immediate needs (Manning & Smock, 2005; Sassler, 2004). Do cohabiting sliders, regardless of socioeconomic status, demonstrate shades of suspended trust? By extension, given the similarities between suspended and compartmentalized trust, a comparable question could be asked about the prevalence of compartmentalized trust among long-term cohabiters in other socioeconomic groups.

The attributes of compartmentalized trust raised other important conceptual and methodological issues for consideration. Throughout the analysis reported here, we were concerned about the ambiguity that surrounded the classification of mothers in the compartmentalized category particularly because the majority was Mexican American. Unlike many of the mothers in the suspended trust category who were forthcoming about the limited transactional nature of their trust behaviors, and about how experiences like physical and sexual abuse affected their behaviors, most mothers in the compartmentalized category appeared to distinctively manage their presentation of self to present a positive image of their relationships and how they placed trust their partners. These behaviors often called the authenticity of their words and actions about trust into question among the ethnographers and data analysts. Thus, we suspect that the classification of compartmentalized trust was more tenuous than the other groupings because we could not be sure whether mothers were simulating a conscious culturally-based required (el que dirán) persona of trust, or whether, given that many of these women had been sexually and physically abused, that they were unconsciously pretending to trust in ways that could be viewed as appropriate. We believe that this category requires further investigation, perhaps focusing initially on the development of new with-in group studies of the trust behaviors of Hispanic women. How prevalent is el que dirán among other socioeconomic groups within Hispanic populations? How does it influence the assessment of trust in romantic unions?

The misplaced trust group posed the greatest challenge to conventional thinking about the development of trust and it is the group that also warranted the most concern. Taken at face value, the mothers in this group appeared to manufacture a brand of trust that allowed them to place trust in their partners too easily and too quickly. The data suggested that these mothers frequently presented inaccurate profiles of their partners to themselves and to others who observed their relationships as a way to temporarily keep their relationships going. In doing so, mothers often put themselves and their children at risk for abuse and financial ruin. Mothers’ impaired judgments about trust seemed to be the result of problems that stemmed from past trauma such as childhood sexual abuse. The levels of physical and sexual abuse that women in this group experienced were extensive. Their patterns serve to heighten family researchers’ awareness of the role of physical and sexual abuse in women’s relationship behaviors and should hasten those who promote marriage programs for low-income women and their partners to carefully consider the impact of misplaced trust when encouraging marriage among at-risk partners. It is likely that a similar warning applies for economically advantaged women who have experienced long-term untreated physical and sexual abuse although the impact on these women’s romantic relationships has received considerably less scholarly attention than those of low-income women.

Among the 4 forms of trust, integrated trust most closely resembled behaviors that were described in existing models of interpersonal trust. For most of the mothers in this category, trust developed progressively along similar lines as the stages of predictability, dependability, and faith described by Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna (1985). Nonetheless, while these mothers demonstrated what some might deem to be normative interpersonal trust behaviors, their relationships were not problem-free. The day-to-day issues associated with poverty took their toll on the strongest of these relationships. As one mother put it, “I have to work 5 times as hard to keep this relationship going because something is always comin’ up and tryin’ to beat us down.” While findings from our study provide a glimpse of how trust operates in these long-term unions, such relationships are not well-understood in family science and warrant further study.

Our analyses and findings clearly illustrated the complexity of studying trust in romantic unions and the need for novel systematic research that can examine these issues in greater detail both with-in and across diverse populations. There were numerous questions that we were not able to address in this work, but that beg close examination. Are the defining features of the trust categories inclusive of dimensions that are the most important to measure (e.g., attention to and reliance on evidence of partners’ trustworthiness; partners’ interdependence)? To what extent do mothers use a range of types of trust within and across their relationships? What factors influence the short and long term use of certain forms of trust? Are elements of situated trust similar for men and women? The Three-City Study was designed to examine the role of poverty and welfare reform across multiple domains in mothers’ everyday lives, and, as such, was not a study specifically focused on evaluating generalized gender or interpersonal trust. To address the questions raised by our analyses requires a longitudinal investigation that explicitly examines the antecedents of trust through childhood and adolescence and explores the trust words and behaviors of low-income men and women beyond a focus on generalized gender distrust and, most importantly, within the situations in which men and women find themselves.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Administration on Children and Families for supporting our research on marriage and romantic relationships among low-income families through grant 90OJ2020 and the National Science Foundation for their support of our work on intergenerational resource allocation through grant SES-07-03968. We also acknowledge core support to the Three-City Study from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through grants HD36093 and HD25936 as well as the support of many government agencies and private foundations. For a complete list of funders, please see www.threecitystudy.johnshopkins.edu. We extend special thanks to Ted Huston, Jessica Thornton Walker, Alexis Walker, Raymond Garrett-Peters, Lynn Smith-Lovin, Anne Fletcher, S. Phillip Morgan, Keith E. Whitfield, and Edward Tiryakian for their insightful suggestions during the preparation of this article. Most importantly, we thank the families who graciously participated in the research reported in this article.

REFERENCES

- Blumer H. Attitudes and the social act. Social Problems. 1955;3(2):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Tucker MB. Romantic unions in and era of uncertainty: A post-Moynihan perspective on African American women and marriage. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621:132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S, England P. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41:237–261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Burton LM, Hurt TR, Purvin D. The influence of physical and sexual abuse on marriage and cohabitation. American Sociological Review. 2004;9:768–789. [Google Scholar]

- Couch LK, Jones WH. Measuring levels of trust. Journal of Research in Personality. 1997;31:319–336. [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher I. Words and deeds: Social science and social policy. Social Problems. 1966;13:235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Drigotas SM, Rusbult CE, Verette J. Level of commitment, mutuality of commitment, and couple well-being. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, England P, Linnenberg K. Love and distrust among unmarried parents; Paper presented at the symposium entitled, “Marriage and Family Formation among Low-Income Couples: What Do We Know from Research?”; Ann Arbor, MI. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas MJ. Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday and Company; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Lopez G. Erotic journeys: Mexican immigrants and their sex lives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. Theoretical sensitivity. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hannerz U. Soulside: Inquires into ghetto culture and community. New York: Columbia University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin R. Trust and trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Melz H. The case for (promoting) marriage: The devil is the details. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:943–958. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Burgess RL. Social exchange in developing relationships: An overview. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson JJ. The intersectionality of domestic violence and welfare in the lives of poor women. Journal of Poverty. 2002;6:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa R. Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:837–857. [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Huston TL. The dyadic trust scale: Toward understanding interpersonal trust in close relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1980;4:595–604. [Google Scholar]

- Leone JM, Johnson MP, Cohan CL, Lloyd SE. Consequences of male partner violence for low-income minority women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:472–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Weigert A. Trust as a social reality. Social Forces. 1985;63:967–985. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z. Serial cohabitation and the marital life course. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:861–878. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Romantic relationships among unmarried African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: Finding from the national survey of American life. Family Relations. 2008;57:254–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K. Latinas’ transition to first marriage: an examination of four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R. Violence and the life course: the consequences of victimization for personal and social development. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ. Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New Perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Marks LD, Hopkins K, Chaney C, Monroe PA, Nesteruk O, Sasser DD. “Together we are strong:” A qualitative study of happy, enduring African American marriages. Family Relations. 2008;57:172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mead GH. Mind, self, and society. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mills CW. Situated actions and vocabularies of motive. American Sociological Review. 1940;5:904–913. [Google Scholar]

- Rainwater L. Behind ghetto walls. New York: Aldine; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Sweeney MM. What explains race and ethnic variation in cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and nonmarital fertility? 2007 Unpublished paper. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel JK, Holmes JG, Zanna MP. Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:95–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. American Psychologist. 1971;26:443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Wieselquist J, Foster CA, Witcher BS. Commitment and trust in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. In: Adams JM, Jones WH, editors. Handbook of interpersonal commitment and relationship stability. NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Acona J. Modos colectivos de conducta: Las vigencias. Revista Mexicana de Sociologia. 1964;26:685–700. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S. The process of entering into cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;6:491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Johnson MP. Attitudes and behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology. 1976;2:161–207. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ. Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations. 2006;55:499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL. Qualitative analysis for social scientists. NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- van de Rijt A, Buskens V. Trust in intimate relationships: The increased importance of embeddeness for marriage in the United States. Rationality and Society. 2006;18:123–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. When work disappears. NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Winston P, Angel RJ, Burton LM, Chase-Lansdale PL, Cherlin AJ, Moffitt RA, Wilson WJ. Welfare, Children, and Families: Overview and design. 1999 Retrieved April 20, 2009 from Johns Hopkins University, Welfare, Children, & Families: A Three-City Study Web site: http://web.jhu.edu/threecitystudy/images/overviewanddesign.pdf.

- Wood GD. Desperately seeking security. Journal of International Development. 2001;13:523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Youm Y, Paik A. The sex market and its implications for family formation. In: Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y, editors. The sexual organization of the city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 165–193. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer VA. The purchase of intimacy. Law and Social Inquiry. 2000;25:817–848. [Google Scholar]