Abstract

This study aimed to understand parents’ evaluations of the way they integrated work-family demands to manage food and eating. Employed, low/moderate-income, urban, U.S., Black, White, and Latino mothers (35) and fathers (34) participated in qualitative interviews exploring work and family conditions and spillover, food roles, and food-choice coping and family-adaptive strategies. Parents expressed a range of evaluations from overall satisfaction to overall dissatisfaction as well as dissatisfaction limited to work, family life, or daily schedule. Evaluation criteria differed by gender. Mothers evaluated satisfaction on their ability to balance work and family demands through flexible home and work conditions, while striving to provide healthy meals for their families. Fathers evaluated satisfaction on their ability to achieve schedule stability and participate in family meals, while meeting expectations to contribute to food preparation. Household, and especially work structural conditions, often served as sizeable barriers to parents fulfilling valued family food roles. These relationships highlight the critical need to consider the intersecting influences of gender and social structure as influences on adults’ food choices and dietary intake and to address the challenges of work and family integration among low income employed parents as a way to promote family nutrition in a vulnerable population.

Keywords: food-choice coping strategy, work-family spillover, food role, gender, family structure

INTRODUCTION

Work-family spillover, characterized as positive and negative feelings, attitudes, and behaviors that may spill over from one domain into another as parents attempt to integrate work and family roles (Googins, 1991), can influence working parents’ personal care, time use, and health behavior (Doumas, Margolin, & John, 2003; Grunberg, Moore, & Greenberg, 1998). Employed parents have identified work to family spillover as a challenge (Devine, Connors, Sobal, & Bisogni, 2003). As family work hours have increased, parents are spending less time on household tasks, including meal preparation, (Bianchi, 2000; Bianchi, 2006; Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006; Sayer, 2005; Shelton, 1992). There has been an increase in meals eaten and prepared away from home (Blisard, Lin, Cromartie, & Ballenger, 2002; Guthrie, Lin, & Frazao, 2002; Economic Research Service, 2006) and a decrease in family meals eaten together (Bianchi, 2006). Focused study of working parents’ food choice strategies can provide valuable insights into a specific behavioral domain that is central to personal and family health.

In earlier qualitative research, we described an emergent conceptual model that included intersecting behavioral, evaluative, and affective processes through which low- and moderate-income parents experienced the relationship of work-family spillover to their food choices (Devine et al., 2006). That study led to a conceptual framework and measures that were subsequently used in a quantitative assessment of these relationships (Devine et al., in press). In that earlier analysis possible gender differences in parents’ experiences of work-family spillover and food choices emerged, especially in evaluations of their food choice strategies. In the current paper we build on our earlier analysis by explicitly examining differences in mothers’ and fathers’ use and evaluations of strategies for the integration of work and family demands. This analysis will provide a grounded interpretation of some of the reasons for gender differences in dietary practices and a foundation for work and family policies aimed at improving those practices.

Gender is a key social characteristic that affects access to health resources, exposure to health risks, and provides clues to social rules about health behaviors such as food choices (Verbrugge, 1982). Gender differences in household structure, employment, and family food roles as well as food choice values and expectations (Connors, Bisogni, Sobal, & Devine, 2001; Sobal, 2005) underscore the importance of examining differences and similarities in mothers’ and fathers’ evaluations of work-family spillover. Socioeconomic gradients in health that vary by gender (MacIntyre & Hunt, 1997) highlight the importance of examining how structural and behavioral factors from both work and family roles contribute to health (Bird & Rieker, 1999; Denton & Walters, 1999).

Gender differences in household structure may influence the experience of work-family spillover. For example, the presence of a spouse and children may affect time and financial demands and contribute to gender differences in the experience of work-family spillover. Mothers are more likely than fathers to head single parent households (Census, 2004). Female-headed households are more than twice as likely to live below the poverty level, compared to those headed by men (Census 2004; 2005). Single mothers are more likely to report work-family spillover (Ciabattari, 2007).

Systematic differences in the employment characteristics of men and women may also contribute to gender differences in work-family spillover. Employed women work fewer average weekly hours than men with 25% of mothers and 3% of fathers working part-time (Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2006). Women are more likely than men to be in the lowest wage occupations (Lichtenwalter, 2005) and to hold multiple jobs; women are less likely to have flexible work schedules. Men, more than women, work night or rotating shifts or weekends (Presser, 2003). In non-managerial, non-professional occupations, women’s jobs fall primarily in the service and clerical sectors, while men’s fall in production and service (BLS, 2005). Occupational conditions are associated with the quality of worker’s diets (Cohen, Stoddard, Sarouhkhanians, & Sorensen, 1998; Hellerstedt & Jeffery, 1997; McCann, Warnick, & Knopp, 1990; Wickrama, Conger, & Lorenz, 1995). Shift work, overtime, and multiple jobs may limit parents’ ability to participate in family meals. Job-related skills or resources such as access to healthful food or time for family tasks may enhance parents’ abilities to meet family demands.

Evaluative experiences of work-family spillover in general may also differ by gender (Dilworth, 2004; Winslow, 2005). Women make more work adjustments (Keene & Reynolds, 2005) and feel more balanced when they make changes to meet family demands. Men report feeling more balanced when they make scheduling changes but less balanced when they have no time for themselves (Keene & Quadagno, 2004).

The relationship between work-family spillover and food choices may be affected by gender differences in expectations for household food work. Household food work has long differed by gender (Bianchi, 2005; Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989; Schafer, Schafer, Keith, & Bose, 1999), although the gap has narrowed as women decreased and men increased time in food preparation (Sayer, 2005). The effect of parenthood and marital status on food preparation time varies by gender. Women who live with a partner or a partner and children have greater odds of spending any time in food preparation than men in similar living situations (Jabs, 2006). Family role expectations may increase opportunities for family meals and provide instrumental and social support for food acquisition and meal preparation (Coltrane, 2000; DeVault, 1991; Schafer & Schafer, 1989).

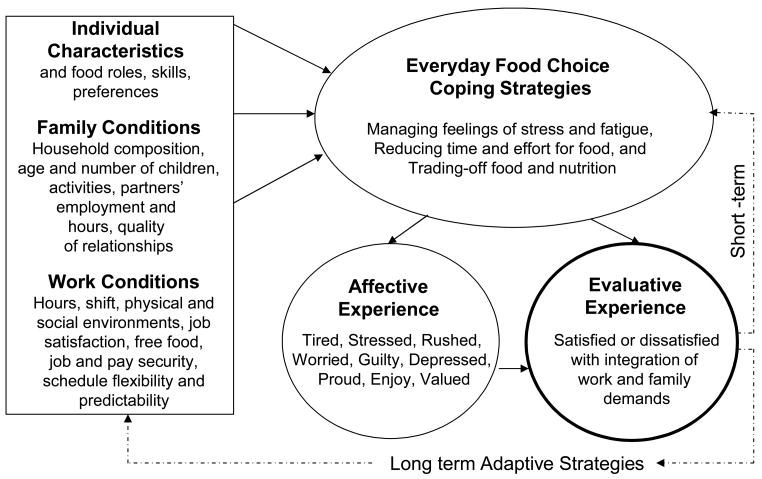

The analysis reported here was guided by our earlier conceptual model for work-family spillover and food choices (Devine et al., 2006). In the model that guided the current analysis (Figure 1) we considered both the “inputs” into (i.e. individual, work and family conditions) and “outputs” from (e.g. evaluative experiences) parents’ use of food-choice coping strategies. In the model, family conditions, work conditions, and individual characteristics are seen as shaping parents’ food-choice coping strategies. Parents used these behavioral food-choice coping strategies to reduce time and effort for food and expectations for food and eating, manage stress and fatigue, and trade-off food and eating against other family needs. Affective experiences reflected parents feelings of being tired, stressed or busy because of competing work and family demands. Evaluative experiences, the focus of this analysis, were conceived as parents’ satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their food-choice coping strategies. Based on their evaluations, parents described continually modifying their everyday food-choice strategies in the short term (e.g. buying take-out food) or using family adaptive strategies (Finch, 1989; Gerson, 1985; Giddens, 1991; Moen & Wethington, 1992), that involved long-term changes in individual food roles or work and family conditions (e.g. reducing work hours). This analysis provided an opportunity to examine how social and economic forces affect family functioning, nutrition, and health.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of employed parents’ experiences of the integration of work and family demands on everyday food choice coping strategies

METHODS

The research design and methods have been described in detail elsewhere (Devine et al., 2006). This theory-guided constructivist investigation used qualitative methods, guided by a conceptual model applying an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). This approach allowed us to explore how mothers and fathers experienced and evaluated their food choice strategies in relation to day-to-day work and family demands.

Study Sample

Parents employed in low- and moderate-wage jobs in a multi-ethnic urban area in Upstate New York were recruited through community agencies, newspaper advertisements, posters in neighborhood stores and worksites, and snowball techniques. All participants worked 20 or more hours a week and had at least one child 16 years or younger living at home three or more days a week. Participants were recruited for diversity in race/ethnicity and job type. Sixty-nine Black, White, and Latino employed mothers (35) and fathers (34) from 25 to 51 years of age participated. Mean age was 36 years for mothers and 39 years for fathers. About 34% had education below the high school level, 45% had some college, and 21% had a college degree. Two-thirds of participants had household incomes below the county median (Census, 2003), with fathers reporting higher incomes than mothers (Table 1). Forty-three percent of mothers were single compared to 15 % of fathers. Study participants worked in service, clerical, retail sales, and production jobs, reflecting gendered occupational patterns in the research community (BLS, 2005). Common jobs among mothers were service and clerical positions and among fathers, service and production positions. Household food roles were described by participants as having personal responsibility for food and meals, shared responsibility with another household member, ones’ partner having primary responsibility, or with no one in the household having responsibility. On-going analysis guided subsequent recruitment that continued until theoretical saturation was reached.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Mothers (35) | Fathers (34) | |

|---|---|---|

| Children in the household | ||

| More than 2 | 10 | 7 |

| Under age 5 | 14 | 12 |

| Over age 13 | 13 | 11 |

| Family living arrangements | ||

| Married/Partner | 19 | 29 |

| Single | 15 | 5 |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 25 | 33 |

| Partners’ employment | ||

| Full-time | 16 | 18 |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$20,000 | 13 | 5 |

| $20–39,999 | 13 | 16 |

| ≥ $40,000 | 9 | 13 |

| Primary home food and cooking role | ||

| Self | 27 | 12 |

| Shared | 4 | 6 |

| Partner | 1 | 12 |

| No one | 3 | 4 |

Data Collection

Two experienced interviewers used a pre-tested, semi-structured interview guide to conduct the one-hour, in-depth qualitative interviews in English in participants’ homes or community settings. The semi-structured interview guide focused on how these working parents managed food and eating. It included open-ended questions and probes about eating and food preparation routines and strategies on work days and non-work days as well as work and family conditions and social processes related to food and eating; food choice coping strategies (e.g. What happens with food and eating when things get busy/on a good day at home/at work?); and personal and family health and nutrition concerns and satisfactions (e.g. How would you describe the way you manage food and eating?). We audio-tape recorded all interviews, produced verbatim transcripts, reviewed transcripts for accuracy, and recorded field notes after each interview. All participants provided written consent according to a protocol reviewed by the University Institutional Review Board and received monetary compensation.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed procedures based on the constant comparative method in continuous data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), and steps were taken to ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of findings. Analytic steps included: 1) review of all interview transcripts and field notes by the research team; 2) weekly peer debriefing on emergent themes; 3) open coding for emergent themes; 4) iterative thematic coding of interviews by three experienced coders using qualitative data analysis software (QSR, 2002); comparison of 2–3 interviews to ensure similar code interpretation; 6) upon emergence of thematic differences between mothers and fathers, re-analysis of interviews to contrast and compare interpretations and themes; 7) selective review of codes related to parents’ satisfaction or dissatisfication with the way work and family demands affected their food and eating; 8) categorization of participants with similar evaluations; 9) comparison of individual characteristics, work and family conditions, food-choice coping strategies, and adaptive strategies by evaluative category and gender; and 10) interpretation of findings in the context of existing conceptualizations and empirical research. Research peers with food choice expertise provided feedback on findings.

RESULTS

The mothers and fathers who participated in this study differed in the ways that they evaluated their ability to integrate work and family demands to feed themselves and their families in a manner that met their personal values, skills, and preferences. While a small number of mothers and fathers expressed satisfaction with the way they were managing food and eating, many others expressed a range of dissatisfaction from overall dissatisfaction with all aspects of their work and family lives to dissatisfaction with only one aspect of their lives including: work (unfulfilling and stressful), family life (demanding and chaotic), or their daily schedule (hectic and rushed). We first briefly describe the general ways that mothers and fathers described their satisfaction and dissatisfaction with food and eating and some similarities in the criteria by which mothers and fathers evaluated their food choice strategies. We then present and illustrate themes emerging from differences in mothers’ and fathers’ evaluations of their food and eating strategies.

Mothers’ and fathers’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with food and eating

These parent’s evaluations included overall satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their food choice strategies in the light of combined work and family demands. Mothers expressed satisfaction when they could achieve work family balance because of flexible work and family schedules. Fathers expressed satisfaction when they had a stable schedule that allowed them to participate in regular family meals. Dissatisfaction was described by mothers as feeling overwhelmed and fathers as feeling overburdened. Parents’ level of satisfaction was distinguished by differences in their depictions of their individual characteristics (e.g. cooking enjoyment, skills, and household food roles), family conditions (e.g. marital status, age and number of children), and work conditions (e.g. schedule, hours, shift), as well as the everyday food-choice coping strategies, and long-term adaptive strategies that they used to manage work and family responsibilities.

Similarities in mothers’ and fathers’ evaluative criteria and strategies

There were several similarities in the criteria used by mothers and fathers to evaluate their satisfaction with their food and eating strategies. Both mentioned individual characteristics (having cooking skills and enjoying cooking) and family conditions (having fewer and older children, fewer family activities at meal times, and a partner who cooked at least some of the time) as conditions that made them feel satisfied with the way they managed food and eating.

Negative work conditions mentioned by both mothers and fathers included stressful jobs, few breaks, long work hours, shifts incompatible with family meals, and disliking jobs or coworkers. Positive work conditions included jobs that provided mental challenges and positive social contacts and occasionally free food. Food choice coping strategies described by both mothers and fathers included meal simplification, multitasking, planning, and speeding up. Changes in household food roles (e.g. who shops and/or cooks) were cited by parents as adaptations that made it possible for them to better integrate work and family responsibilities and feel more satisfied with their choices.

Thematic differences in mothers and fathers evaluative criteria and strategies

There were many differences in mothers’ and fathers’ evaluations of the way they managed food and eating (summarized in Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in mothers’ (n=34) and fathers (n=35) criteria for evaluating and strategies for managing work and family demands

| Individual Characteristics | Family Conditions | Work Conditions | Daily Food Choice Coping Strategies | Long-term Adaptive Strategies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | + Has help with food | + Older children | + Flexible schedule | Get help with meals | Change job/hours |

| − Wants more help with food | − Many children | + PT schedule | Treat with food | Limit family activities | |

| − Young child | + Morning shift | Trade off own nutrition | Change household food roles | ||

| − Need to get children ready in AM | − Inflexible schedule | Trade off child nutrition | |||

| Skip meals | |||||

| Fathers | + Prefer partner cook | + Regular family meals | + Regular schedule | Plan work meals | Change attitude towards job |

| + Partner works ≤ PT | + Regular hours | Trade off family meals | |||

| + Food low priority | + Good family relationships | + Flexible breaks | |||

| + Overtime | |||||

| − Wants partner to cook more/better | − Partner works | + Valued at work | |||

| − Partner works FT | − Irregular schedule | ||||

| − Step child | − Job insecurity | ||||

| − Blended home | − Opposite shift from partner | ||||

| − Hostile family relationships | |||||

| − Partner fatigue | |||||

| − Partner stress | |||||

| − Many family activities |

Seeking Balance and Stability

Mothers explained that satisfaction was based on their ability to balance work and family demands through flexible work and home conditions. One single mother described how flexible work hours, the ability to turn down overtime when she didn’t have childcare coverage, a decision to home school her son, and a good neighbor who was willing to look after her son while she worked the evening shift, made it possible for her to make healthy meals and spend more time with her son during the day.

Fathers’ evaluations were based on their ability to achieve schedule stability, particularly to take part in regular family meals. One satisfied father described how his wife’s part-time work hours and flexible schedule allowed him to enjoy a family meal most nights: “[her hours] were just flexed for her so she can work from ten to two and what that allowed us to do is not need a baby sitter in the evenings as before, but now she can get the kids off to school and then pick them up.” A divorced father described meals with his two sons as “the stable island in the rest of the chaos of their lives.” In contrast, a dissatisfied father’s second shift job meant that he could only eat with his family on weekends.

Getting Help and Giving Help

Mothers emphasized that getting help from family members with household food tasks was positive, while having young children who could not help and limited help from other family members created difficulties. Satisfied mothers typically held the primary household food role, liked to cook, and expected and received help with food tasks. A mother with a 15 year old daughter and a husband who returned from work at mid-afternoon said, “I have wonderful help, my husband and my daughter, I mean without them, I couldn’t do it. You know I think that would be more stress on me, you know, running home, cooking, cleaning up… because of them it’s easier… and I’m very fortunate for that.”

Fathers’ expressed satisfaction when they had a partner who took the primary household food role and made regular family meals. One father explained differences in the way he and his partner viewed cooking at home:

“I think it [home cooking] makes it [eating] less stressful but I think my partner [laughs] would say it makes it more stressful… I’m sure she would like to have someone cook for her more but… I will [cook] once in a while... cause once in a while like if she’s only gonna be home for a certain amount of time, I’ll [cook]... one of our compromises is we have spaghetti.. cause it’s.. easy.

Family conditions: lifestage, family size, and relationships

Satisfied mothers described having older children who helped with household food tasks. Half of the mothers who expressed satisfaction had children over 13 years of age; only two had children less than five years old. Dissatisfied mothers described how multiple family demands, especially having young children, made them feel overwhelmed. Four of the nine mothers expressing overall dissatisfaction had children less than five years of age. All of the mothers who said that they were dissatisfied with their jobs and two-thirds of those who described demanding family lives had more than two children. One mother with a full-time clerical job, a husband who traveled for his work, and a pre-school daughter described her family pressures this way:

“I’m the one who cooks, all the time. [My husband’s] a courier, so a lot of times he won’t even be home. It’s hard… because… I can’t come home and decompress.”

“I have to work around [my daughter’s] time schedule. … A lot of times… I get so caught up in doing things, sometimes I will forget to eat. … I’ll snack on something here and there but as far as making a meal I won’t. … It’s a lot on my plate. … There’s times that I could go and just cry for a little bit and then just breathe and then start back up on my normal routine again.”

Seven of the nine overall dissatisfied mothers were single and by default had the primary household food role; two were married, but did not get help with food. Six worked full-time. These mothers described their food responsibilities as an unwanted burden and expressed frustration over a lack of family support and help with food tasks.

Fathers who had stable work and family schedules expressed satisfaction with the way they integrated demands. One father, when asked how he dealt with food and eating in spite of a hectic life, talked about eating on schedule; “It’s all the same… no change in the meals… still gotta eat no matter how stressed you get… it’s a repetitive thing. I mean every day is the same thing.” For these fathers, satisfaction often went hand-in-hand with having a partner who did not work outside the home or worked only part-time. Ten of the eleven fathers expressing overall satisfaction were married or had a partner; nine of these partners either did not work outside the home or worked only part-time.

Dissatisfied fathers talked about partners who were not available to take charge of food and meals at home. Five of these fathers had partners who worked, four of them full-time. Two of these fathers complained that they had the primary food role at home because their wives were at school or work in the evening. Dissatisfied fathers described irregular family meal schedules as a major strain. One father described meals in his house as, “sporadic, fly-by-the-seat-of -our pants type cooking.” He listed some of the circumstances that contributed to unpredictability of meals: “[my wife] has to do overnights… [I’m] double shift which is required… when the kids are sick… There’s a lot of things going on.” For fathers, but not mothers, other family members’ problems contributed to unpredictable meals and dissatisfaction. These fathers described the challenges of coordinating with their partner’s work schedule, coping with their partner’s work stress, and hostile family relationships or blended households as sources of dissatisfaction. A father of three whose wife worked a late afternoon shift wished his family could: “get away from the take out. More away from that, and more at home. You know hopefully in five years my wife won’t be workin til six, seven o’clock at night, and we can have meals earlier. We can plan out better meals.” Another father said that when things got: “too stressful for my wife she doesn’t feel like cooking.” Some of these conditions were seen as temporary while partners finished school or recovered from illness or post-partum depression. Like single mothers, single fathers described having little or no help at home when their children were staying with them. One single father had arranged for a daycare provider to feed his children.

Work conditions: flexibility and regularity

Flexible work schedules, short commutes, and jobs that allowed them to be home in the afternoon and evening were named as key resources in mothers’ efforts to integrate multiple demands. One mother’s job was “nearby… a pleasant work environment. They… allow me flexibility.” Half of the overall satisfied mothers worked part-time.

Dissatisfied mothers described poor work conditions, inflexible schedules, and disliked jobs as contributors to dissatisfaction. One mother gave an example:

“[work] gets crazy where you’re almost sick to your stomach, because you’re just trying to get everything done, you’re completely frazzled so you don’t even think about eating” … “if [my boss] wants you to stay late, you have to stay late. If she wants you in early, you have to be in early.” … “Everything seems to revolve around my hours of work.”

Satisfied fathers described full-time jobs, consistent schedules that allowed regular family meals, flexible breaks, optional overtime, free food, good relationships with coworkers, and jobs they liked. One father said, “I love the people I work with.”

Fathers who expressed dissatisfaction described insecure, stressful jobs, and unsatisfying jobs, irregular schedules, and shifts that meant missing their families. One father said: “There’s no job security. [A] lot of our work is leaving the plant. And that leaves a lot of stress amongst the employees… I’ve been laid off before and it’s no fun… and that puts a lot of stress on the family.” Another father said “We don’t have any breaks… we get paid flat rate, so if you’re working you’re getting paid… You don’t get paid by a clock pay … for me I get the worst jobs and it gets harder.” Food choice coping strategies: skipping, treating, and trading off

In most households one adult had a primary food role; mothers were twice as likely as fathers to say they held this role (Table 1). Mothers also described using more kinds of food-choice coping strategies than fathers. Satisfied mothers manged by getting help with meals, planning meals, and treating themselves and others with food. Dissatisfied mothers also described treating themselves or others with food and asking for help with meals, but in addition they skipped meals and traded-off personal and occasionally child nutrition to save time and energy. Mothers with less family support described multiple trade-offs. One mother said, “If I don’t have time to cook, I will just… microwave something quick… which I don’t like to do a lot… instead of the healthier meals that I want to cook.” All of these mothers described pushing through, coping, and getting things done with the little time, energy, or resources available.

Fathers described fewer and less varied food choice strategies, although those with more responsibility for food talked about speeding-up and making family meal trade-offs. A father with one full time and two part-time jobs described some dissatisfactory trade offs:

“I never would have… been using like [brand name], uh, canned ravioli and stuff, but the kids like it. … So, when time is short, and because it’s usually coupon-based and on-sale, that’s in the cupboard, but it’s not… it’s not my first choice and it’s usually done because… it’s either that or a fast food restaurant, so this would be 2 compromises that go against my jib, so to speak…”

Family adaptive strategies: changing jobs and changing attitudes

Mothers who expressed satisfaction described family adaptive strategies they had used to ease up work and family demands. These adaptations included changes in jobs and schedules and the number of family evening and weekend activities. One mother described her choices this way: “My number one thing is to make sure that my kids are well taken care of… … You can always change jobs but you don’t want to see your kids mess up.” Satisfied mothers talked less about guilt than other mothers and, although tired, were proud of their ability to manage multiple demands and enjoy family meals. Dissatisfied mothers described having made few adaptations, but many talked about wanting to make changes. One mother said, “[my job] gets very wearing, and tired and boring. So I go ‘oh my god I need to find me another jooobb.”

Satisfied fathers adaptive strategies were more commonly described as changes in their attitudes to ‘keep work issues at work,’ minimize family stress, and adapt to changes in household food roles. One father had slowly transitioned to become the family cook when his wife “finally told me “You’re gonna have to help me.” Then when I started doing it I realized I enjoyed it… I know she was busy and after awhile it just got to the point where I prefer to do it and I got better at it.” A few fathers wished they could change their jobs to spend more time with the family, but none had done so. Rather they described job changes by their partners to make things flow more smoothly at home.

DISCUSSION

Differences in the experiences and evaluations of mothers and fathers reflected intersecting gender and structural explanations for the ways these employed parents managed and evaluated personal and family food choices. While both mothers and fathers felt tired, rushed and stressed, they evaluated these experiences to a large extent on their ability to enact household food roles.

A gender perspective suggests that differences in mothers’ and fathers’ use and evaluation of food-choice coping strategies are related to persistent gender-role expectations that reinforce gender inequality and power relationships between men and women (Sayer, 2005). Descriptions of work and family demands in this study reflected between-gender differences and similarities in affective, evaluative and behavioral domains. While both mothers and fathers described feeling rushed, stressed and tired, only mothers expressed guilt about the ways they integrated demands and how that affected their food-choice coping strategies. Most mothers described working and trying to hold onto food roles at home as part of what has been called an effort to sustain their “moral identities” as good mothers (Backett-Milburn, Airey, & McKie, 2008 p. 16). Fathers, more than mothers, described financial worries. With a few exceptions, fathers were trying to be good providers while trying to help out with food and meals at home. These differences in interpretation reflect traditional gender orientations with mothers holding cultural responsibility for food and meals (Charles & Kerr, 1988; DeVault, 1991; Murcott, 2000;Schafer & Schafer, 1989), and fathers for financial support.

Mothers and fathers described a range of food-choice coping strategies but their use of strategies reflected gender differences. Satisfied mothers reported many more food-choice coping strategies and more frequent trade-offs. Fathers’ infrequent reports of trade-offs may have reflected that mothers were often in charge, even if the work was shared. Mothers who were responsible for family food and meals depended on skills and multiple trade-offs to find balance. These findings are supported by quantitative differences in the food choice coping strategies used by mothers and fathers in response to demanding work conditions (Devine et al., in press). DeVault (1991) described mothers use of the resources at hand to make adjustments and trade-offs. The strategies that were the focus of this study are typical of low schedule control household tasks frequently done by women (Barnett & Shen, 1997).

Mothers and fathers also differed in their interpretation of shared responsibilities for cooking and reasons for taking primary responsibility. Mothers managed their own skills and time, sometimes requesting or receiving help. With some exceptions, fathers talked of providing help to someone else, like Coltrane’s (1989) observation that cooking help is viewed differently by the giver and the receiver. It is interesting that some fathers with primary food roles who lived in two-parent households described this choice in terms of enjoying cooking or cooking skills. Mothers who enjoyed cooking focused more on their ability to meet the needs of other family members, especially children, as has been described previously (DeVault, 1991).

A structural perspective suggests that differences in use and evaluations of food-choice coping strategies are related to gender-specific economic and structural conditions that affect access to resources (Sayer, 2005). Our findings provide some support for this interpretation. Our small purposive sample was like the population at large in that a greater proportion of mothers were single parents, worked part-time, had lower incomes, and worked in service-sector jobs (BLS, 2006,BLS, 2007). This combination left many of these mothers, especially the single mothers, feeling the effects of work-family spillover more acutely, having less money, and usually less time.

Adaptive strategies to reduce conflicting demands were more commonly described by mothers in this study, consistent with the work of Keene and Reynolds (2005). These mothers may have seen their employment as more expendable because they made less money or their caretaking time at home was more valuable. Crompton (2006) has written that the high demands and low satisfaction offered by many low-wage jobs means that low income women may seek satisfaction at home. Many parents, but especially mothers, wished they could work fewer hours or not at all, only one job, or different shifts to allow more time for children and family meals. However, these adaptive strategies were not presented as possible by many respondents. This reflects the low-wage jobs of our study participants and stands in contrast to studies of higher income parents where mothers, in particular, reported using a variety of adaptive strategies (Becker & Moen, 1999; Gerson, 1985).

The food roles of these parents mirrored the current population with more than half of married or partnered participants saying mothers held the main responsibility for family food. This matches the continued dominance of women as family food managers who spend twice as much time as men on family food preparation. The shared cooking roles described by about a fifth of the married study participants reflect the closing gap between men and women (Jabs, 2006; Murcott, 2000; Sayer, 2005; Schafer & Schafer, 1989). It was notable that participants attributed shared cooking roles, not to mothers’ employment, but to employment conditions (e.g. opposite shifts), family conditions (e.g. presence of an infant), or individual characteristics (e.g. poor health). This is consistent with women’s roles as default family food managers. In households where fathers had primary food responsibility, family conditions contributed to this arrangement, but so did personal preferences and skills. Taking a lead cooking role at home and pride in cooking skills may be one of a number of new scripts for masculinity related to food (Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Jastran, & Devine, 2008; Sobal, 2005).

Our findings provide support for an interpretation in which work and family role conditions such as quality, fit, and satisfaction provided clues to food-choice coping strategies (Barnett & Gareis, 2006; Barnett, Gareis, & Brennan, 1999). Among these low-wage parents both work and family conditions were described as contributors to the use of and evaluation of food-choice coping strategies. Becker (1965) wrote of the dependence of household time allocation on the skills held by and the opportunities open to family members. In our study fathers typically reported higher incomes and mothers more cooking skills. When fathers had greater cooking skills or mothers more earning opportunities, food roles were reversed. Parents, but especially fathers, also expressed dissatisfaction with missing meals because of overtime or late shifts, often undertaken for higher wages or reduced child care costs. Additional support for a structural explanation is seen in the ways food roles changed with changing work and family conditions. This is consistent with Swidler’s (1986) interpretation of culture in action in the way that parents in this study expressed preferences for idealized traditional food roles but were able to act strategically as the situation demanded.

The intersection of gender and structural explanations became most apparent when we considered emergent within-gender differences in evaluations. Both mothers and fathers described a level of satisfaction that was based on structural and demographic conditions, interpreted in gendered ways. The relationship between food roles and dissatisfaction among fathers and the relationship between help at home and dissatisfaction among mothers clearly demonstrate the intersection of gendered and structural explanations. When both parents were employed, fathers were most satisfied when work schedules allowed them to be home for meals prepared by their partners, and mothers were most satisfied when their schedules were flexible enough to allow them to prepare those meals, albeit with some help from other family members.

Goals for the integration of demands differed by gender. These mothers sought flexibility and balance while fathers sought schedule stability. Like the young working women in Scotland described by Backett-Milburn, Burley & Kemmer (2001), mothers who could achieve balance through a flexible work schedule felt better able to adjust to the needs of their families. In fact, mothers’ flexible work schedules allowed them to set up and implement personal and family food routines that made schedule stability possible for the rest of the family. Family meals have been recognized as highly symbolic rituals (Fiese et al., 2002) that, when routinized provide a setting for enactment of family roles. Routines and rituals such as family meals have been described as patterns of activity that demonstrate power relationships and sustain families (DeVault, 1991). The schedule stability exemplified by regular family meals may have allowed the fathers in our study to find a familiar place in families where formerly well-defined gender roles had become blurred.

Overwhelmed mothers and overburdened fathers felt that they could not even attempt the goals of balance and stability, so instead they coped by adjusting their goals downwards. It is striking that in seven two-parent households no one took responsibility for food and eating. Devine et al. (2006) have described the devaluing of food and meals among working parents when work and family conflict. This raises questions about who will do the food work, if it is viewed as no one’s responsibility. Brannen and Nilsen (2005) and Kristensen and Holm (2006) have pointed out the need to consider the conditions in which people make choices, with particular attention to whether the resources are available to meet needs and goals. Many of these parents did not believe they had the time, money, or skills to achieve their ideals for family food and meals. While some parents may be able to make adaptations and shift priorities to achieve their food and eating ideals; many others will not be able to do this without broad societal support for changes in work and family policies.

This study had a number of strengths and some limitations. Low-wage workers are an important group due to their higher risk for poor nutrition and health. Our focus on low- and medium-wage parents allowed us to understand their perspectives in-depth, including important differences in mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of work-family spillover. There is a need to investigate these findings in a more economically diverse sample. Differences between mothers and fathers in employment and family characteristics make this especially important. Those who participated may have been able to better manage their time than parents who did not participate.

Macintyre and Hunt (1997 p. 328) called for a need to understand how social structural positions such as those created by employment and income “actually mean for the everyday lives of men and women” and how these things “impact on health, health-related behaviour, and ability to cope with threats in the physical and social environment.” The findings of this study show the practical effect of the intersection of structural conditions, interpreted in gendered ways, on working parents’ management of stressors from often conflicting work and family demands and the effect on their food choices. The good news is that, in spite of often considerable barriers, most of these mothers were striving to be actively involved in providing healthy meals for their families and most of these fathers were striving to participate in family meals. The bad news is that gendered work and household structures often served as significant barriers to parents trying to fulfill these valued family food roles. Family meals have been positively associated with diet quality (Gillman et al., 2000; Larson, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, & Story, 2007; Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, Story, Croll, & Perry, 2003; Videon & Manning, 2003) and protection from obesity among children and adolescents (Fulkerson, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, & Story, 2008; Gable, Y., & Krull, 2007; Larson et al., 2007; Sen, 2006). In addition, mothers’ work status affects the frequency of family meals, with full-time working mothers having fewer family meals than those who work part-time, who have fewer than those who are not employed (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2003). These relationships highlight a need to address work-family spillover among employed parents as a way to promote child nutrition and prevent excess weight gain.

Jacob et al., (2008) have recently shown a mediating effect of family dinnertime on some of the negative outcomes of long work hours including success in personal life, family relationships, and the perception of an emotionally healthy workplace. Among women, these authors showed that being present for family dinners could reduce the work-family conflict that has been associated with long work hours. Thus satisfaction with food and eating and being able to participate in family dinners may have benefits for employers as well as employees and their families.

Because we found a broad range of family food provisioning models and strategies, different workplace policies and supports may be needed for workers with different work and family conditions (Barnett & Rivers, 2004). Employers need to take into account the importance of workplace policies and practices such as work hours, overtime work, work breaks, shift work and schedules on their employees’ food choice strategies and satisfaction and foster parents’ ability to share healthy meals with their families. For example, these could include schedule flexibility for working mothers, schedule stability for working fathers, or healthy take home meals for parents.

These findings also point to the need to consider the intersecting influences of gender and social structure in research on adults’ food choices and dietary intake. Research in this area needs to acknowledge the different ways that mothers and fathers experience work and family integration using a wide range of coping strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jennifer Jabs, PhD, RD for conducting interviews, organizing and coding data, and providing feedback on findings. Funding was provided by the National Cancer Institute (RO1CA102684-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christine E. Blake, Email: ceblake@sc.edu.

Carol M. Devine, Email: cmd10@cornell.edu.

Elaine Wethington, Email: ew20@cornell.edu.

Margaret Jastran, Email: mmc17@cornell.edu.

Tracy J. Farrell, Email: tjf6@cornell.edu.

Carole A. Bisogni, Email: cab20@cornell.edu.

References

- Backett-Milburn K, Airey L, McKie L. Family comes first or open all hours?: how low paid women working in food retailing manage webs of obligation at home and work. Sociological Review. 2008;56(3):474–496. [Google Scholar]

- Backett-Milburn K, Cunningham-Burley S, Kemmer D. Caring and Providing: Lone and Partnered Mothers Working in Scotland. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation/Family Policy Studies Centre; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett R, Gareis K. Role theory perspectives on work and family. In: Pitt-Catsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S, editors. The Work and Family Handbook: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett R, Rivers C. Same Difference: How Gender Myths are Hurting our Relationships, Our Children, and Our Jobs. New York: Basic Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Gareis KC, Brennan RT. Fit as a mediator of the relationship between work hours and burnout. Journal of Occupational and Health Psychology. 1999;4:307–317. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Shen Y-C. Gender, high- and low- schedule control housework tasks, and psychological distress. Journal of Family Issues. 1997;18(4):403–428. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A theory of the allocation of time. The Economic Journal. 1965;75(299):493–517. [Google Scholar]

- Becker PE, Moen P. Scaling back: dual earner couples’ work-family strategies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61(4):995–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces. 2000;79(1):191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. “What gives” when mothers are employed? Time allocation of employed and nonemployed mothers: 1975 and 2000. Department of Sociology and Maryland Population Center. University of Maryland; 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. “What gives” when mothers are employed? Parental time allocation in dual earner and single earner two-parent families. Department of Sociology and Maryland Population Center. University of Maryland; 2006. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie M. Changing Rhythms of American Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bird CE, Rieker PP. Gender matters: an integrated model for understanding men’s and women’s health. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake C, Bisogni C, Sobal J, Jastran M, Devine CM. How adults construct evening meals: scripts for food choice. Appetite. 2008;51:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blisard N, Lin B-H, Cromartie J, Ballenger N. America’s changing appetite: food consumption and spending to 2020. Food Review. 2002;25(1):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, DeLongis A, Kessler R, Wethington E. The contagion of stress across multiple roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brannen J, Nielsen A. Individualisation, choice and structure: a discussion of current trends in sociological analysis. Sociological Review. 2005;53(3):412–428. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments By Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. (BLS) Wages by Area and Occupation - data for men and women in 200 occupations. 2005 Retrieved July 17, 2006, from the World Wide Web: http://www.bls.gov/bls/blswage.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U. S. (BLS) Women in the labor force: A databook. 2006 Retrieved, from the World Wide Web: http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook2006.htm.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U. S. (BLS) Employment characteristics of families in 2007. 2007 Retrieved 8/20/2008, from the World Wide Web: www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.nr0.htm.

- Census Bureau, U. S. Median household income. 2003 Retrieved July 17, 2006, from the World Wide Web: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Products/Ranking/2003/R07T050.htm.

- Census Bureau, U. S. Family structure and children’s living arrangements: percentage of children ages 0–17 by presence of married parents in household, race and Hispanic origin, selected years 1980–2004. 2004 Retrieved, from the World Wide Web: www.census.gov/population/www/sodemo/hh-fam.html.

- Census Bureau, U.S. Percent Distribution of Households, by Selected Characteristics within Income Quintile and Top 5 Percent in 2004. 2005 June 24; Retrieved June 13, 2007, from the World Wide Web: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032005/hhinc/new05_000.htm.

- Charles N, Kerr M. Women, Food and Families. New York: Manchester University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ciabattari T. Single mothers, social capital, and work-family conflict. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(1):34–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N, Stoddard A, Sarouhkhanians S, Sorensen G. Barriers toward fruit and vegetable consumption in a mutiethnic worksite population. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1998;30:381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Household labor and the routine production of gender. Social Problems. 1989;36(5):473–490. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1208–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Connors M, Bisogni C, Sobal J, Devine C. Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite. 2001:189–200. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton R. Employment and the Family: The Reconfiguration of Work and Family Life in Contemporary Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Denton M, Walters V. Gender differences in structural and behavioral determinants of health: an analysis of the social production of health. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;48:1221–1235. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVault M. Feeding the Family. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Devine C, Connors M, Sobal J, Bisogni C. Sandwiching it in: spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine C, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farrell T, Bisogni C. “A lot of sacrifices:” Work-family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage working parents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(10):2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Farrell T, Blake C, Jastran M, Wethington E, Bisogni C. Work conditions and the food choice coping strategies of low/moderate income employed parents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth JEL. Predictors of negative spillover from family to work. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Margolin G, John RS. The relationship between daily marital interaction, work, and health-promoting behaviors in dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(1):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Research Service. Food CPI, Prices and Expenditures: Food Away from Home. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2007, from the World Wide Web: http://www.ers.usda.gov/briefing/CPIFoodAndExpenditures/Data/table3.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Backer T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:381–390. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch J. Family obligations and social change. Cambridge, MA: B. Blackwell; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family Meal Frequency and Weight Status among Adolescents: Cross-sectional and 5-year Longitudinal Associations. Obesity. 2008;16:2529–2534. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SYC, Krull JL. Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson K. Hard Choices: How Women Decide about Work, Career, and Motherhood. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gillman M, Rifas-Shiman S, Frazier A, Rockett H, Camargo C, Field A, Berkey C, Golditz G. Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(3):235–240. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Googins BK. Work/family conflict: Private lives, public responses. New York: Auburn House; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg L, Moore S, Greenberg ES. Work stress and problem alcohol behavior: A test of the spillover model. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1998;19(5):487–502. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz J, Marks N. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational and Health Psychology. 2000;5(1):111–126. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Lin B-H, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: changes and consequences. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2002;34(3):140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt W, Jeffery R. The association of job strain and health behaviors in men and women. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;26(3):575–583. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J. Time for food: Qualitative and quantitative investigations of issues of time and food preparation. Cornell University; Ithaca, NY: 2006. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob JI, Allen S, Hill EJ, Mead NL, Ferris M. Work interferences with dinnertime as a mediator and moderator between work hours and work and family outcomes. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 2008;36:310–327. [Google Scholar]

- Keene JR, Quadagno J. Predictors of perceived work-family balance: gender difference or gender similarity? Sociological Perspectives. 2004;47:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Keene JR, Reynolds JR. The job costs of family demands. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen S, Holm L. Modern meal patterns: tensions between bodily needs and the organization of time and space. Food & Foodways. 2006;14:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:1502–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenwalter S. Gender poverty disparity in US cities: evidence exonerating female-headed families. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2005;32:75–96. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre S, Hunt K. Socioeconomic position gender and health. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2(3):313–334. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann BS, Warnick GR, Knopp RH. Changes in plasma lipids and dietary intake accompanying shifts in perceived workload and stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1990;52:97–108. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Wethington E. The concept of family adaptive strategies. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Murcott A. Invited presentation: Is it still a pleasure to cook for him? Social changes in the household and the family. Journal of Consumer Studies and Home Economics. 2000;24(2):78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M, Croll JK, Perry C. Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. Journal of The American Dietetic Association. 2003;103(3):317–322. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presser HB. Race-ethnic and gender differences in nonstandard work shifts. Work and Occupations. 2003;30:79–95. [Google Scholar]

- QSR. QSR Nvivo 2 (Version 3) Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer L. Gender, time and inequality: trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work, and free time. Social Forces. 2005;84(1):285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer E, Schafer RB, Keith PM, Bose J. Self-esteem and fruit and vegetable intake in women and men. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1999;31:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer RB, Schafer E. Relationship between gender and food roles in the family. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1989;21:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sen B. Frequency of family dinner and adolescent body weight status: evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth, 1997. Obesity. 2006;14(12):2266–2276. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton BA. Women, men and time: Gender differences in paid work, housework, and leisure. New York: Greenwood Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J. Men, meat and marriage: models of masculinity. Food and Foodways. 2005;13:135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler A. Culture in action: symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review. 1986;51:273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. Women’s Social Roles and Health. In: Berman P, Ramsey R, editors. Women, A Developmental Perspective. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1982. pp. 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM, Manning CK. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: the importance of family meals. J Adolescent Health. 2003;32(5):365–373. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00711-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K, Conger R, Lorenz F. Work, marriage, lifestyle, and changes in men’s physical health. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;18(2):97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01857863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow S. Work-family conflict, gender, and parenthood, 1977–1997. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26(6):727–755. [Google Scholar]