Abstract

In this study we generated 3D poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogel arrays to screen for the individual and combinatorial effects of extracellular matrix (ECM) degradability, cell adhesion ligand type, and cell adhesion ligand density on human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) viability. In particular, we explored the influence of two well-characterized ECM-derived cell adhesion ligands: the fibronectin-derived Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro (RGDSP) sequence, and the laminin-derived Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV) sequence. PEG network degradation, the RGDSP ligand, and the IKVAV ligand each individually increased hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner. The RGDSP ligand also improved hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner in degradable PEG hydrogels, while the effect of IKVAV was less pronounced in degradable hydrogels. Combinations of RGDSP and IKVAV promoted high viability of hMSCs in nondegradable PEG networks, while the combined effects of the ligands were not significant in degradable PEG hydrogels. Although hMSC spreading was not commonly observed within PEG hydrogels, we qualitatively observed hMSC spreading after 5 days only in degradable PEG hydrogels prepared with 2.5 mM of both RGDSP and IKVAV. These results suggest that the enhanced throughput approach described herein can be used to rapidly study the influence of a broad range of ECM parameters, as well as their combinations, on stem cell behavior.

Introduction

Hydrogel networks have emerged as an important component of several stem cell–based tissue engineering strategies, which aim to use engineered biomaterials to promote tissue formation by stem cells. For example, human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) have been included within various synthetic [e.g., poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)1 and poly(ethylene glycol fumarate)]2 and naturally derived (e.g., collagen,3 fibrin,4 and agarose3) hydrogel matrices, and induced to differentiate into functional osteoblasts,5 chondrocytes,1 myoblasts,6 and adipocytes.7 These previous studies have generated cartilage,8 bone,9 skeletal muscle,10 and adipose11 tissues within hydrogel matrices, and recent studies have made significant advances toward forming composite tissue structures as well. For example, Mao and coworkers have demonstrated that MSC-derived chondrocytes and osteoblasts embedded in hydrogels can generate tissues that mimic the structure of the natural articular condyle.9 Taken together, these previous studies suggest that combinations of hydrogels and hMSCs may serve as useful constructs for a range of musculoskeletal tissue engineering applications. However, control over MSC behavior within hydrogel matrices remains a significant challenge.

Early studies of hMSCs embedded within hydrogel matrices indicate that extracellular matrix (ECM)–derived signals strongly influence stem cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation, and differentiation in a 3D context.12 The recognition that stem cell behavior can be influenced by characteristics of the local 3D environment has led several investigators to develop controllable 3D environments for stem cell culture. A subset of these approaches has focused on presenting specific biological moieties (e.g., cell adhesion ligands, and growth factors) while avoiding nonspecific interactions with other biological molecules. Notable examples of these “blank slate” biomaterials include PEG,13,14 agarose,15 and alginate12 hydrogels. PEG hydrogels have been a particularly prevalent biomaterial in stem cell–based tissue engineering applications, as they are resistant to nonspecific protein interactions, amenable to simple chemical modification schemes,16 and readily processed to form stem cell–laden hydrogels.14 For example, Elisseeff and coworkers have shown that ECM-derived cell adhesion ligands or soluble growth factors incorporated into PEG hydrogels can promote osteogenesis and chondrogenesis by MSCs.17 In addition, Anseth and coworkers have demonstrated that the polysaccharide heparin18 or the corticosteroid dexamethasone19 can promote osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs when immobilized within a PEG network. These studies and others demonstrate that stem cell behavior within synthetic hydrogels can potentially be regulated by controlled exposure to inductive biological molecules. However, it remains challenging to identify and deliver the optimal signaling environments needed to encourage stem cell viability, lineage-specific differentiation, and tissue formation.

Hydrogel matrices can, in principle, be designed to mimic elements of natural extracellular environments and to present inductive environments to stem cells.12 However, different natural ECMs contain widely variable concentrations of particular signals, such as particular cell adhesion proteins. In addition, natural ECMs typically present complex combinations of signals to cells simultaneously to orchestrate cell behavior. In contrast, it is often not practical to examine the effects of widely variable signal concentrations, or complex combinations of signals, within synthetic ECMs such as hydrogel networks. Therefore, novel engineering approaches are needed to efficiently examine the effects of specific ECM-derived signals and signal combinations on stem cell behavior. To that end, we and others have recently focused on developing 3D cell culture systems with enhanced throughput capabilities. In one approach, photolithographic methods have been used to generate spatially patterned hydrogel structures with distinct regions that contain specific cell types,20 cell adhesion ligands,21 or ECM chemistries.21 For example, Pishko and coworkers have used photopolymerization within microchannels21 or spots22 to generate PEG microstructures, and demonstrated that multiple mammalian cell types remain viable in hydrogels for up to 7 days. We have previously developed an automated approach to generate PEG hydrogel arrays, which were designed to present a widely adaptable range of ECM-derived signals to multiple cell types in a 3D context.23 This general approach can be used to locally present a wide range of signal concentrations and signal combinations to cells in a 3D context. Taken together, these previous studies demonstrate that it is possible to create spatially patterned, cell-laden hydrogel “arrays,” and that 3D hydrogel array formats provide a promising platform for enhanced throughput stem cell culture studies.

In this study we used 3D PEG hydrogel arrays as platforms to screen for the individual and combinatorial effects of multiple ECM parameters on hMSC viability. Specific ECM parameters explored here include cell concentration, ECM degradability, cell adhesion ligand type, and cell adhesion ligand concentration. We specifically studied two ECM-derived cell adhesion peptides, the fibronectin-derived Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro (RGDSP) sequence and the laminin-derived Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV) sequence. These sequences were chosen based on previous studies that indicate that fibronectin and laminin mediate hMSC attachment in standard cell culture conditions, thereby influencing hMSC adhesion and differentiation.24 In this study we specifically characterize hMSC viability, since tissue formation in most stem cell–based tissue engineering applications is likely to require a high concentration of viable, tissue-forming stem cells. Previous studies from Anseth and coworkers indicate that when hMSCs are cultured in PEG hydrogels with no biological cues provided, cell viability drops dramatically to less than 30% within 7 days in vitro,14,23 and to less than 10% after 4 weeks in vitro.23 Therefore, it is critical to identify environments that promote and maintain long-term hMSC viability in 3D PEG hydrogel networks. The results presented here provide an initial demonstration that hydrogel arrays can be used to identify ECM signals that promote hMSC viability in a 3D context. This hydrogel array format may ultimately represent a useful general platform for enhanced throughput screening of various ECM parameters on multiple stem cell behaviors, including self-renewal and differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of synthetic PEG hydrogel arrays

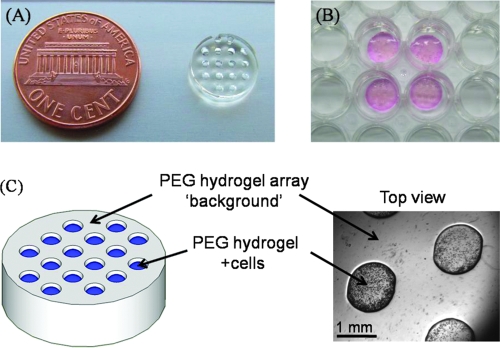

Poly(ethylene glycol) with a molecular weight of 8 kDa was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The synthesis of PEG-diacrylate (PEGDA) was performed as described elsewhere,25 and PEG hydrogels were prepared as described previously.23 Briefly, hydrogel “precursor solution” was prepared by mixing 10 wt% PEGDA and 0.05%w/v photoinitiator Irgacure 2959 (I2959; BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) in serum-free minimum essential medium, alpha 1× (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 2.2 g/L NaHCO3 (ACROS Organics, Geel, Belgium) and 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin, and was passed through a 0.22 μm filter for sterilization. Then the precursor solution was added to a Teflon® (DuPont, Wilmington, DE) mold containing 16 cylindrical posts (1 mm diameter, 1.25 mm depth), and crosslinked via exposure to UV radiation (λ = 365 nm, intensity = 4.5 mW/cm2) for 5 min to form a hydrogel “background,” which contained an array of 16 cylindrical spots (Fig. 1). The array spots were then automatically filled with the aforementioned precursor solution, with hMSCs included, using an automated liquid handler (as detailed below).

FIG. 1.

(A) 8 kDa PEG hydrogel array “background” showing an array of 16 cylindrical spots. (B) Image demonstrating four representative PEG hydrogel arrays within a 12-well tissue culture plate. (C) Schematic representation and brightfield image of array spots filled with cell-laden PEG hydrogels. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

In some experiments, PEG hydrogel arrays were designed to degrade hydrolytically over time using an approach described elsewhere.23,25 Briefly, 8 kDa PEGDA chains were reacted with variable amounts (2.5 or 5 mM) of dithiothreitol (DTT; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) in serum-free medium at 37°C for 60 min to form water-soluble, acrylate-terminated (PEG-DTT)n-PEG conjugates. Cells were then added to the polymer solution, and the solution was photocrosslinked as described above to create PEG hydrogels with “DTT bridges” included. The ester bonds adjacent to thioether groups in these bridges degrade hydrolytically, and the concentration of the bridges therefore dictates the hydrolytic degradation rate of PEG network, as detailed in our previous studies.23,25 As a result, PEG hydrogels containing DTT bridges are referred to as “degradable” networks in subsequent sections of this manuscript, while PEG hydrogels without DTT bridges are referred to as “nondegradable.” Degradation of DTT-containing PEG hydrogel arrays was characterized by measuring their equilibrium swelling ratio after various incubation times in PBS, as described previously.25 Briefly, hydrogel arrays were placed in a 2 mL PBS solution and incubated at 37°C for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Hydrogel arrays were weighed (wet weight, ws), then incubated in DI water to remove buffer salts, lyophilized for 48 h, and weighed again (dry weight, wd). Three replicates were used. The mass equilibrium swelling ratio (Qm) was calculated according to the equation:

|

In some experiments, acrylate-terminated PEG chains or (PEG-DTT)n-PEG conjugates were reacted with peptides containing the fibronectin-derived cell adhesion ligand RGDSP or the laminin-derived cell adhesion ligand IKVAV to generate cell-interactive hydrogel networks. In these experiments a 10× excess of acrylate-terminated PEG chains (Mw = 8 kDa) or (PEG-DTT)n-PEG conjugates were incubated with a CGGRGDSP and/or a CGGIKVAV peptide for 90 min in PBS (37°C, pH 7.4) to allow for Michael-type addition of the cysteine sulfhydryl group to the acrylate group, as described previously.16,26,27 The resulting solutions contained PEGDA and acrylate-PEG-CGGRGDSP and/or acrylate-PEG-CGGIKVAV molecules, which were subsequently photocrosslinked to form cell-interactive hydrogel networks.

A standard protocol for solid-phase peptide synthesis using Fmoc-chemistry was followed for the synthesis of CGGRGDSP and CGGIKVAV. Peptides were synthesized on Rink Amide resin (0.72meq functional amine group/g) (Novabiochem, San Diego, CA) at a scale of 0.2 mmol on a C036s automated peptide synthesizer (CSBio, Menlo Park, CA). Briefly, amino acid couplings were performed by introducing a 2.5 × molar excess of Fmoc-protected amino acids (Novabiochem) activated with N-Hydroxybenzotriazole · H2O (Advanced Chemtech, Louisville, KY) and N,N-diisopropylcarbodiimide (Anaspec, San Jose, CA) to the resin in sequencing-grade dimethylformamide (Fisher Scientific). Prior to each coupling, Fmoc-protecting groups were removed using a 20% solution of Piperidine by volume (Sigma-Aldrich) in dimethylformamide. Upon completion of synthesis, peptides were cleaved from the resin using a solution of 95% Trifluoracetic Acid (Fisher Scientific), 2.5% Triisopropylsilane (Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 2.5% H2O, and precipitated into 4°C ethyl ether (Fisher Scientific). The peptides were washed three times in ethyl ether and left for 2 days to dry. The amino acid compositions of the peptides were verified on a Bruker REFLEX II MALDI-ToF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) and via HPLC (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MO).

Biological characterization of hydrogel arrays

Cell culture

hMSCs (passage 6; Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD) were cultured in minimum essential medium, alpha (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cambrex), 2.2 g/L NaHCO3 (ACROS Organics), and 100 units/mL of penicillin/streptomycin. Cell cultures were maintained at 37°C/5% CO2, and media was replaced every 3–4 days. To maintain multipotency, hMSCs were grown at low density using the method described previously by Sotiropoulou et al.28

Cell-seeding within PEG hydrogel arrays

Cells were photoencapsulated in a 10 wt% polymer solution (final concentration) in serum-free media at a seeding density of 5 × 105 cells/mL, unless otherwise stated. The cell/polymer solution (1 μL) was pipetted in the wells of the hydrogel array using a Gilson automated liquid handler (Model: 223 Sample Changer) and Trilution LH version 1.2 control software (Gilson Inc., Middleton, WI) at a rate of approximately 5 spots/min. Upon ultraviolet light exposure for 3 min, PEG-based hydrogels were cross-linked and cells were physically entrapped within the networks. The arrays were then placed in media and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2, replacing media every 2–3 days.

Cell viability within hydrogel arrays

After photoencapsulation, the arrays were removed from culture at various time points (1, 3, 5, and 7 days) and were stained using the LIVE/DEAD assay (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This assay identifies esterase activity in live cells via green fluorescence emission from calcein AM and nuclear permeability in dead cells via red fluorescence emission from ethidium homodimer-1. Arrays were analyzed using an inverted, compound fluorescence microscope (IX51, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Cell viability was visualized, and the total percentage of viable cells was determined by manual analysis of live and dead cells in photomicrographs for at least four images (40× magnification) per condition. The cell density in wells was measured by obtaining at least five images of the same well in different focal planes from the top to the bottom of the well. At least three samples per condition were analyzed. It is noteworthy that during the analysis of seeding density (Fig. 2D) the total number of all live and dead cells in all planes of each array spot was counted 24 h after encapsulation, and averaged. In some conditions, cell morphology in hydrogel array spots was also characterized qualitatively using the same fluorescence microscope described above.

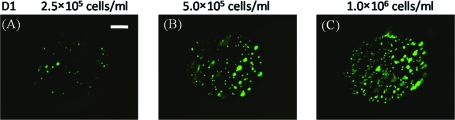

FIG. 2.

(A–C) hMSCs seeded in wells of a nondegradable PEG hydrogel array at various cell seeding densities: (A) 2.5 × 105 cells/mL, (B) 5 × 105 cells/mL, and (C) 1.0 × 106 cells/mL, respectively. Scale bar = 200 μm. (D) Relationship between cell concentration in the hydrogel precursor solution and cell concentration measured in the wells. Data are shown for both nondegradable (no DTT) and degradable (2.5 and 5 mM DTT) hydrogels. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviations for four samples per condition or three samples per condition (in cell density analysis). Note that conditions with 0 mM ligand concentrations are presented in multiple bar graphs in Figures 4–6 (white bars) to facilitate comparison between the 0 mM ligand conditions and other experimental conditions. Differences between data sets were assessed by one-way ANOVA analysis. In some cases, Tukey's two-way analysis was performed using the R software package. Regardless of the test, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

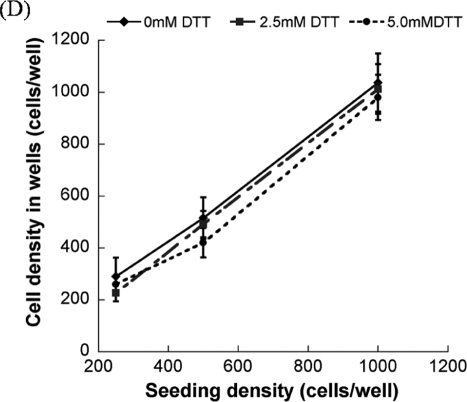

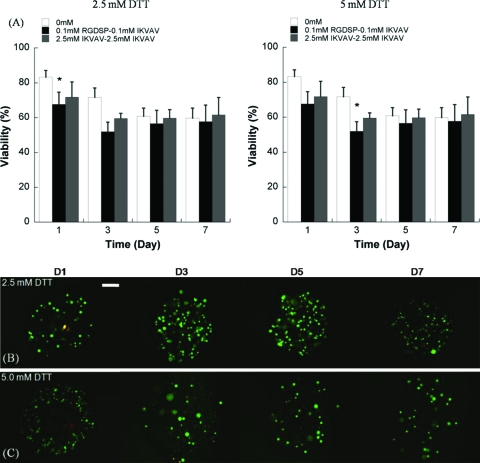

FIG. 4.

Quantitative analysis of hMSC viability within nondegradable PEG hydrogel arrays containing (A) variable concentrations of the RGDSP ligand and (B) variable concentrations of the IKVAV ligand. (C) Quantitative analysis of hMSC viability in nondegradable PEG hydrogel arrays with various combinations of the RGDSP and IKVAV ligands. (D–G) hMSC viability does not decrease significantly between day 1 and day 7 in PEG hydrogels containing both 2.5 mM RGDSP and 2.5 mM IKVAV, as demonstrated here via live/dead staining. Scale bar = 200 μm. Asterisks (*) denote a significant difference compared to 0 mM ligand concentration at the same time point; ANOVA p < 0.05. Color images available online at www .liebertonline.com/ten.

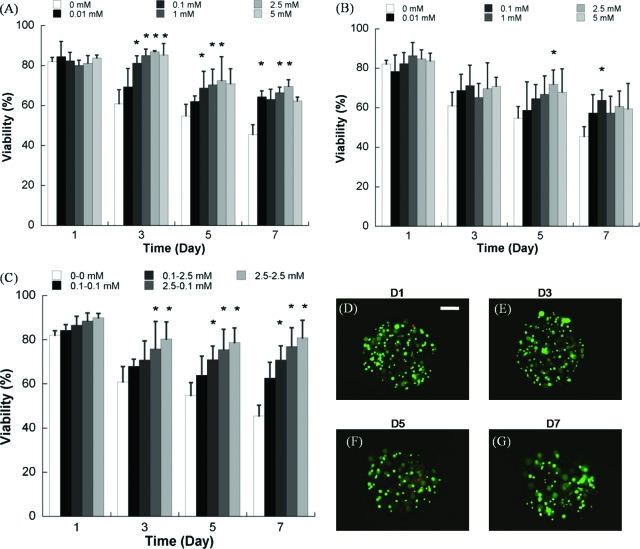

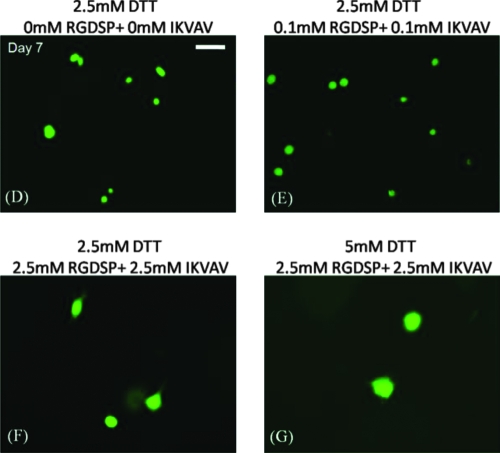

FIG. 6.

(A) Quantitative analysis of hMSC viability within degradable hydrogel arrays (2.5 or 5 mM DTT) containing various combinations of RGDSP and IKVAV. (B, C) Live/dead images of hMSC cultured in degradable PEG hydrogel spots containing 2.5 mM RGDSP and 2.5 mM IKVAV, and (B) 2.5 mM DTT or (C) 5 mM DTT. Scale bar = 200 μm. (D–G) Higher magnification images of hMSCs cultured in degradable PEG hydrogel arrays at 7 days: (D) 2.5 mM DTT + no adhesion ligands; (E) 2.5 mM DTT + 0.1 mM RGDSP + 0.1 mM IKVAV; (F) 2.5 mM DTT + 2.5 mM RGDSP + 2.5 mM IKVAV; and (F) 5 mM DTT + 2.5 mM RGDSP + 2.5 mM IKVAV. Scale bar = 50 μm. Asterisks (*) denote a significant difference from 0 mM ligand concentration at the same time point; p < 0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Results

hMSC culture in 3D PEG hydrogel arrays without cell adhesion ligands

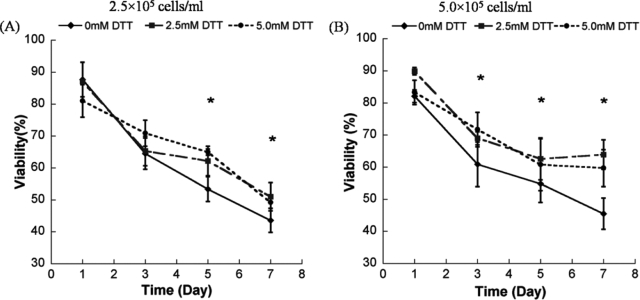

The hMSC seeding density in hydrogel array spots can be controlled and varied over a range of 2.5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells/mL by simply varying the cell concentration in the solution added to array spots (Fig. 2A–C), as described previously.23 There was a direct correlation between the number of cells initially seeded during array preparation and the number of cells quantitatively measured within both nondegradable and degradable PEG hydrogel array spots 24 h after array preparation (Fig. 2D; R2 > 0.99). An increase in cell seeding density from 2.5 × 105 to 1.0 × 106 resulted in a slight, but not significant, trend of increasing hMSC viability at 5 and 7 days after initial cell seeding (Fig. 3A–C).

FIG. 3.

Viability of hMSC's seeded in wells of nondegradable and degradable PEG hydrogel arrays at various cell seeding densities: (A) 2.5 × 105 cells/mL, (B) 5 × 105 cells/mL, and (C) 1.0 × 106 cells/mL, respectively. (D–F) Live/Dead images demonstrating the influence of matrix degradation on viability of hMSCs seeded at 5.0 × 105 cells/mL into arrays with varying degradability: (D) 0 mM DTT (nondegradable), (E) 2.5 mM DTT, and (F) 5 mM DTT. Scale bar = 200 μm. Asterisks (*) denote a significant difference compared to nondegradable hydrogel condition within the same time point; ANOVA p < 0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

The initial equilibrium swelling ratio (Qm) of hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 mM DTT bridges (25.5 ± 1.1) or 5 mM DTT bridges (29.7 ± 1.0) was higher than the Qm of hydrogels containing no DTT (22.2 ± 1.3) (Table 1). This trend of increasing equilibrium swelling ratio can be attributed to an increase in the average molecular weight of chains at the outset of photocrosslinking, which is due to step growth polymerization of PEGDA in the presence of DTT.25 In addition, hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 or 5 mM DTT increased their equilibrium swelling ratio with incubation time in PBS, consistent with hydrolytic degradation of ester bonds in the network (Table 1), as described previously.23,25

Table 1.

Equilibrium Swelling Ratio (Qm) Over Time of Nondegradable PEG Hydrogels and Degradable PEG Hydrogels Containing DTT

| |

Equilibrium swelling ratio (Qm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTT (mM) | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 5 | Day 7 |

| 0 | 22.2 ± 1.3 | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 22.1 ± 0.2 | 22.20 ± 0.3 |

| 2.5 | 25.5 ± 1.1 | 25.8 ± 1.2 | 26.5 ± 0.7 | 27.48 ± 2.1 |

| 5 | 29.70 ± 1.0 | 29.9 ± 0.6 | 30.3 ± 0.4 | 31.88 ± 1.8 |

We observed that there was a significant increase in hMSC viability in degradable PEG hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 or 5 mM DTT when compared with PEG hydrogel arrays without DTT included (Fig. 3). This influence of degradation on hMSC viability was apparent at multiple time points (3, 5, and 7 days) and with multiple cell seeding densities (2.5 × 105, 5.0 × 105, and 1.0 × 106 cells/mL) (Fig. 3; ANOVA p < 0.05). Cells displayed a rounded morphology, and cell spreading was not observed in any degradable or nondegradable PEG hydrogels prepared without cell adhesion peptides included.

Screening for the influence of ECM-derived ligands on hMSC viability

PEG hydrogel arrays were used as an enhanced throughput culture system to screen for the effects of multiple ECM parameters, individually or in combination, on hMSC viability. Covalent incorporation of the fibronectin-derived cell adhesion peptide RGDSP or the laminin-derived cell adhesion peptide IKVAV into nondegradable PEG hydrogel networks enhanced hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A, B). After 7 days in culture hMSC viability decreased to 45.5 ± 4.9% of initial cell viability in nondegradable arrays without RGDSP included, while viability was significantly higher in hydrogel arrays containing 0.01, 0.1, 1, 2.5, and 5 mM RGDSP (64.4 ± 2.9%, 63.1 ± 5.1%, 66.5 ± 2.7%, 69.6 ±3.4%, and 62.3 ± 1.8%, respectively). hMSCs in hydrogel arrays containing 0.01, 0.1, 1, 2.5, and 5 mM IKVAV also showed significant increases in viability at 7 days (57.4 ± 9.3%, 63.9 ± 5.1%, 57.4 ± 8.4%, 60.7 ± 7.8%, and 59.4 ± 12.9%, respectively). Combinations of RGDSP and IKVAV included into the PEG hydrogel arrays also improved hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner at all time points (Fig. 4C). Seven days after initial cell seeding hMSC viability was 62.6 ± 7.2% in hydrogel containing 0.1 mM RGDSP and 0.1 mM IKVAV, while viability increased to 70.8 ± 6.4%, 76.9 ± 8.6%, and 80.9 ± 7.9% in hydrogel array spots with RGDSP/IKVAV concentration of 0.1 mM/2.5 mM, 2.5 mM/0.1 mM, and 2.5 mM/2.5 mM, respectively. It is noteworthy that in the case of 2.5 mM/2.5 mM RGDSP/IKVAV, there was no significant decrease in hMSC viability from day 1 to day 7, indicating that the combination of these ligands support hMSC viability for extended timeframes.

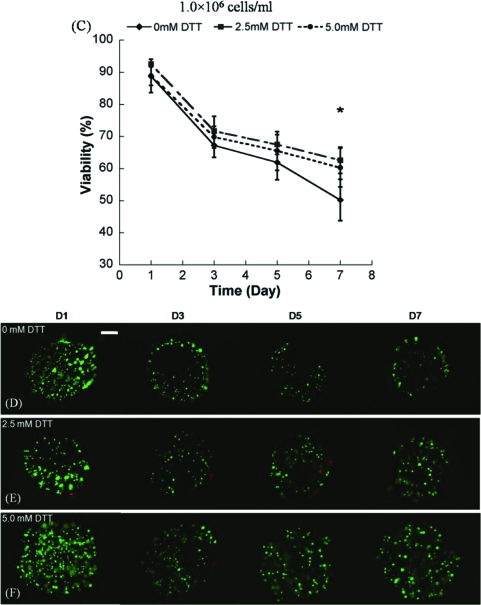

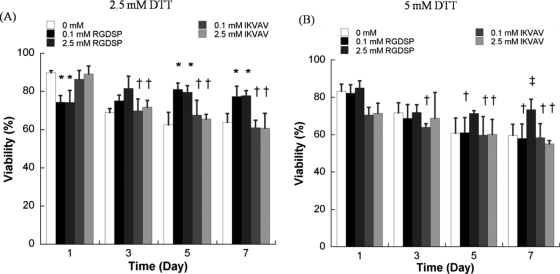

The effects of RGDSP on hMSC viability were also apparent in degradable hydrogel arrays (Fig. 5). The presence of 0.1 or 2.5 mM RGDSP significantly enhanced hMSC viability 5 and 7 days after cell seeding in degradable hydrogels prepared with 2.5 or 5 mM DTT (Fig. 5). In contrast, the presence of IKVAV did not improve hMSC viability 3, 5, or 7 days after cell seeding in degradable hydrogels prepared with either 2.5 or 5 mM DTT. It is noteworthy that in degrading hydrogel arrays with the maximum amount of RGDSP included (2.5 mM), there is no decrease in viability of hMSCs between day 1 and day 7 (Fig. 5), indicating that the presence of a high concentration of RGDSP alone supports hMSC viability during synthetic ECM degradation.

FIG. 5.

Quantitative analysis of hMSC viability within degradable PEG hydrogel arrays with varying degradability, cell adhesion ligand type, and cell adhesion ligand concentration. (A) hMSC viability in degradable PEG hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 mM DTT with variable concentrations of RGDSP or IKVAV, (B) hMSC viability in degradable PEG hydrogel arrays prepared with 5 mM DTT with variable concentrations of RGDSP or IKVAV. Asterisks (*) denote a significant difference from 0 mM concentration at the same time point. Double dagger (‡) denotes a significant difference from all other experimental conditions at the same time point. Daggers (†) denote a significant difference from the T = 1 day value for the same experimental condition; p < 0.05.

Interestingly, the combined influence of RGDSP and IKVAV on hMSCs was less pronounced in degradable PEG hydrogel arrays (Fig. 6) when compared to nondegradable PEG hydrogel arrays (Fig. 4C). hMSC viability after 7 days in degradable hydrogel arrays prepared with 5 mM DTT with RGDSP/IKVAV concentrations of 0.1 mM/0.1 mM (57.7 ± 9.6%) and 2.5 mM/2.5 mM (61.6 ± 9.9%) was lower when compared with hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 mM DTT with RGDSP/IKVAV concentrations of 0.1 mM/0.1 mM (66.7 ± 7.3%) and 2.5 mM/2.5 mM (73.3 ± 3.7%). hMSC behavior in nonmodified PEG hydrogels, in degradable PEG hydrogels without adhesion ligands, or in PEG hydrogels with low concentrations of one or more cell adhesion ligands (0.1 mM) all displayed a rounded morphology (Fig. 6D–E). This rounded morphology is consistent with a variety of previous studies of cell encapsulation in PEG networks (e.g., ref. 14). However, we observed uncommon hMSC spreading after 7 days in degradable PEG hydrogels prepared with 2.5 mM of both RGDSP and IKVAV (Fig. 6F, G).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that an automated approach can be used to generate PEG hydrogel arrays, in which the stem cell concentration and hydrogel network properties can be modulated. Our results indicate that hydrogel array spots can be filled automatically at a rate of 5 spots/min, and that the hMSC concentration in each hydrogel array spot is directly correlated to the stem cell concentration in the hydrogel precursor solution (Fig. 2; R2 > 0.99). Therefore, these arrays can be used to characterize the influence of cell concentration on hMSC behavior. An increase in hMSC concentration led to a slight, but not significant, increase in hMSC viability. Although it was not specifically studied here, hMSC concentration has been previously shown to impact differentiation down the chondrogenic and osteogenic pathways.29–31 Therefore, the array-based approach described here may ultimately be used to explore the impact of cell density on hMSC differentiation with enhanced throughput.

PEG hydrogel arrays can also be designed to degrade hydrolytically over time using a simple, previously described chemistry.23,25 The propensity of hydrogels to change their physical properties over time during degradation has been an inherent challenge in previously developed high-throughput approaches for 3D cell culture.32 For example, when hydrogels are synthesized within the confines of a rigid mold (e.g., PDMS and silicon), they are not able to undergo isotropic swelling to equilibrium, and their physical properties during swelling, degradation, and erosion are likely to differ from the properties of a free-standing hydrogel. The approach described herein creates a background material and spots that degrade in a controllable manner.23 Therefore, the background can be designed to swell and degrade in concert with array spots to explore the influence of degradation on cell behavior. Our results indicate that hydrogel degradation significantly increases hMSC viability, even in the absence of ECM-linked cell adhesion ligands. Increased viability may be attributed to enhanced mass transport in degrading hydrogel networks, as well as a decrease in the physical confinement of hMSCs. It is noteworthy that this result is consistent with previous studies from our group25 and Wang et al.,33 which indicate that ECM degradation is a key factor that directly influences hMSC viability.

The array-based format described herein can also be used to control the type and concentration of ECM-derived cell adhesion ligands, and results indicate that the fibronectin-derived RGDSP ligand enhances hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner. Previous studies have shown that RGDSP improves hMSC viability upon and within PEG hydrogels.14,17,34 For example, Nuttelman et al. reported that PEG hydrogel networks prepared with covalently linked RGD ([RGD] = 2.8 mM) improved hMSC viability up to 75% when compared with the unmodified PEG hydrogel (15% viability) after 1 week in culture, and they postulated that an increase in RGD concentration could perhaps result in even higher hMSC viability.14 Our results corroborate their observation that RGDSP promotes hMSC viability in 3D PEG hydrogels. However, when RGDSP was included at a series of concentrations (0.01–5 mM), the maximal enhancement in hMSC viability was found at [RGDSP] = 2.5 mM at all time points studied (Fig. 4A). This result suggests that PEG hydrogel arrays can be used to screen for the influence of a broad range of ligand concentration on stem cell behavior and to optimize the effects of a particular signal on 3D hMSC behavior.

When hMSCs were cultured in degradable hydrogel arrays, hMSC viability was dependent on both RGDSP concentration and hydrogel degradability. Both lower (0.1 mM) and higher (2.5 mM) RGDSP concentrations promote greater hMSC viability in degradable hydrogel arrays prepared with 2.5 mM DTT, while only the higher concentration (2.5 mM) significantly enhanced hMSC viability in degradable hydrogel arrays prepared with 5 mM DTT. This result indicates that hydrogel swelling has a negative effect on RGDSP-mediated increases in hMSC viability. This effect may be attributed, in part, to decreases in the effective ligand concentration when the swollen volume increases, as higher initial ligand concentrations would be needed to maintain a high ligand presentation to cells within a degrading network.

The laminin-derived IKVAV sequence also promotes enhanced hMSC viability in a dose-dependent manner in nondegradable PEG hydrogels. The IKVAV sequence, found in laminin's α1 chain, has previously been shown to promote cell adhesion, neurite outgrowth, and tumor metastasis.35–37 Our results show that the incorporation of IKVAV into nondegradable PEG networks enhances hMSC viability during 7 days of culture (Fig. 4B). This result is consistent with a previous study, in which Gronthos et al.38 demonstrated that bone marrow stromal stem cells in 2D culture adhered and proliferated on several ECM proteins, including fibronectin, laminin, collagen, and vitronectin. It is noteworthy that the effect of IKVAV on hMSC viability was more modest when compared with the aforementioned effect of RGDSP. These comparative results are consistent with a previous study, in which Salasznyk et al. reported six- to eightfold greater hMSC adhesion to fibronectin when compared to laminin-1, and implicated distinct integrin receptors in adhesion to each of these ECM proteins.24

Interestingly, we have shown here that the presence of IKVAV alone neither improved hMSC viability nor promoted hMSC spreading when included within degradable PEG hydrogels (Fig. 5). It is possible that the effects of IKVAV on hMSCs require a high ligand concentration, and that the ligand concentration is depleted during hydrogel degradation, as postulated above for RGDSP. In addition, it is possible that hMSCs in degradable PEG networks are able to elaborate their own ECM more effectively when compared with nondegradable hydrogel networks, and the cell-secreted ECM proteins may mask the impact of the IKVAV ligand linked to the PEG network.

Combinations of RGDSP and IKVAV ligands positively influenced hMSC viability in nondegradable PEG networks at all time points tested (Fig. 4C; p < 0.05). Interestingly, hMSC viability is not enhanced within degradable hydrogel arrays with both peptides incorporated when compared to unmodified hydrogel networks. Although cell spreading is not commonly observed within PEG hydrogels with or without cell adhesion ligands, we observed hMSC spreading after 7 days in degradable PEG hydrogels prepared with high concentrations (2.5 mM) of both RGDSP and IKVAV (Fig. 6F, G).

Taken together, our results indicate that a combination of cell adhesion ligand type, ligand density, and ECM degradability influence hMSC viability in 3D PEG hydrogel arrays. Appropriate combinations of ECM parameters, identified herein, may be used to enhance stem cell viability and spreading in PEG networks, and therefore these results may provide useful insights for stem cell–based tissue engineering. This enhanced throughput approach to 3D stem cell culture is not limited to the signals explored in this study. It is possible to incorporate other ECM-derived ligands, cell types, or soluble factors directly within hydrogel arrays in an automated fashion. Therefore, these hydrogel arrays could be a useful platform for development of new tissue engineering matrices and for studying the influence of a variety of extracellular signals on stem cell behavior. Although the current study focuses on screening for environments that promote hMSC viability, stem cell proliferation, and differentiation may ultimately be explored in these 3D environments.39–41 Previous studies indicate that the cell adhesion ligands studied here42 or their corresponding ECM proteins43–48 are capable of regulating osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs. Therefore, it is possible that hMSCs incorporated into the PEG hydrogel arrays described here can differentiate to varying extents based on the characteristics of the ECM environment. The approach described here may ultimately be used to construct a more complete analysis of the impact of ECM-derived signals on stem cell behavior.

Conclusions

hMSCs can be exposed to controlled ECM-derived signaling environments within PEG hydrogel arrays spots using an automated process. Here we demonstrate that these arrays can be used to screen for the individual and combinatorial effects of cell concentration, ECM degradability, cell adhesion ligand type, and cell adhesion ligand density on hMSC viability. Results indicate that both the fibronectin-derived RGDSP ligand and the laminin-derived IKVAV ligand have significant, dose-dependent effects on hMSC viability in nondegradable PEG hydrogel networks. In degradable hydrogel networks, only a higher concentration of RGDSP positively influenced hMSC viability when compared with nondegradable networks. In degradable hydrogels, IKVAV incorporation did not improve hMSC viability, indicating that the influence of IKVAV is dependent on network degradability. Incorporation of both RGDSP and IKVAV into nondegradable PEG hydrogels significantly enhanced hMSC viability, and this effect was less pronounced in degradable PEG hydrogels. Importantly, hMSCs generally displayed a rounded morphology, and only demonstrated spreading within degradable PEG hydrogels containing higher concentrations (2.5 mM) of both RGDSP and IKVAV combined. Taken together, these results suggest that hydrogel arrays can be used to rapidly study the influence of a broad range of synthetic ECM parameters on stem cell viability, which is vital to emerging stem cell–based tissue engineering approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R21EB005374 and R21HL084547 to W.L.M) and the National Science Foundation (CAREER award 0745563 to W.L.M. and graduate fellowship to W.J.K.). We also acknowledge Jay Warrick and Dr. David Beebe at the University of Wisconsin for assistance with automated liquid handling.

References

- 1.Salinas C.N. Cole B.B. Kasko A.M. Anseth K.S. Chondrogenic differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells photoencapsulated within poly(ethylene glycol)-arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-serine thiol-methacrylate mixed-mode networks. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1025. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temenoff J.S. Park H. Jabbari E. Conway D.E. Sheffield T.L. Ambrose C.G. Mikos A.G. Thermally cross-linked oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) hydrogels support osteogenic differentiation of encapsulated marrow stromal cells in vitro. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:5. doi: 10.1021/bm030067p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batorsky A. Liao J.H. Lund A.W. Plopper G.E. Stegemann J.P. Encapsulation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells within collagen-agarose microenvironments. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:492. doi: 10.1002/bit.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim H.J. Kim U.-J. Vunjak-Novakovic G. Min B.-H. Kaplan D.L. Influence of macroporous protein scaffolds on bone tissue engineering from bone marrow stem cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4442. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marom R. Shur I. Solomon R. Benayahu D. Characterization of adhesion and differentiation markers of osteogenic marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:41. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnishi S. Nagaya N. Prepare cells to repair the heart: mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of heart failure. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:301. doi: 10.1159/000102000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H.-K. Lee B.-H. Park S.-A. Kim C.-W. The proteomic analysis of an adipocyte differentiated from human mesenchymal stem cells using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2006;6:1223. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang N.S. Varghese S. Zhang Z. Elisseeff J. Chondrogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cells in arginine-glycine-aspartate modified hydrogels. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2695. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alhadlaq A. Elisseeff J.H. Hong L. Williams C.G. Caplan A.I. Sharma B. Kopher R.A. Tomkoria S. Lennon D.P. Lopez A. Mao J.J. Adult stem cell driven genesis of human-shaped articular condyle. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:911. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000032454.53116.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassem M. Mesenchymal stem cells: biological characteristics and potential clinical applications. Cloning Stem Cells. 2004;6:369. doi: 10.1089/clo.2004.6.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauney J.R. Nguyen T. Gillen K. Kirker-Head C. Gimble J.M. Kaplan D.L. Engineering adipose-like tissue in vitro and in vivo utilizing human bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with silk fibroin 3D scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5280. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drury J.L. Mooney D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutolf M.P. Hubbell J.A. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuttelman C.R. Tripodi M.C. Anseth K.S. Synthetic hydrogel niches that promote hMSC viability. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:208. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uludag H. De Vos P. Tresco P.A. Technology of mammalian cell encapsulation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;42:29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutolf M.P. Hubbell J.A. Synthesis and physicochemical characterization of end-linked poly(ethylene glycol)-co-peptide hydrogels formed by Michael-type addition. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:713. doi: 10.1021/bm025744e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang F. Williams C.G. Wang D.A. Lee H. Manson P.N. Elisseeff J. The effect of incorporating RGD adhesive peptide in polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel on osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5991. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benoit D.S.W. Anseth K.S. Heparin functionalized PEG gels that modulate protein adsorption for hMSC adhesion and differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:461. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuttelman C.R. Tripodi M.C. Anseth K.S. Dexamethasone-functionalized gels induce osteogenic differentiation of encapsulated hMSCs. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;76:183. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albrecht D.R. Tsang V.L. Sah R.L. Bhatia S.N. Photo- and electropatterning of hydrogel-encapsulated living cell arrays. Lab Chip. 2005;5:111. doi: 10.1039/b406953f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh W.G. Itle L.J. Pishko M.V. Molding of hydrogel microstructures to create multiphenotype cell microarrays. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5783. doi: 10.1021/ac034773s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koh W.G. Revzin A. Pishko M.V. Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogel microstructures encapsulating living cells. Langmuir. 2002;18:2459. doi: 10.1021/la0115740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongpaiboonkit L. King W.J. Lyons G.E. Paguirigan A.L. Warrick J.W. Beebe D.J. Murphy W.L. An adaptable hydrogel array format for 3-dimensional cell culture and analysis. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3346. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salasznyk R.M. Williams W.A. Boskey A. Batorsky A. Plopper G.E. Adhesion to vitronenctin and collagen I promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;1:24. doi: 10.1155/S1110724304306017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudalla G.A. Eng T.S. Murphy W.L. An approach to modulate degradation and mesenchymal stem cell behavior in poly(ethylene glycol) networks. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:842. doi: 10.1021/bm701179s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy W.L. Dillmore W.S. Modica J. Mrksich M. Dynamic hydrogels: translating a protein conformational change to a macroscopic volume difference. Angewandte Chemie Int Ed. 2007;46:3066. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutolf M.P. Tirelli N. Cerritelli S. Cavalli L. Hubbell J.A. Systematic modulation of Michael-type reactivity of thiols through the use of charged amino acids. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:1051. doi: 10.1021/bc015519e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sotiropoulou P.A. Perez S.A. Salagianni M. Baxevanis C.N. Papamichail M. Characterization of the optimal culture conditions for clinical scale production of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:462. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kavalkovich K.W. Boynton R.E. Murphy J.M. Barry F. Chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells within an alginate layer culture system. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2002;38:457. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2002)038<0457:cdohms>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt B. Ringe J. Haupl T. Notter M. Manz R. Burmester G.R. Sittinger M. Kaps C. BMP2 initiates chondrogenic lineage development of adult human mesenchymal stem cells in high-density culture. Differentiation. 2003;71:567. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2003.07109003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benoit D.S.W. Durney A.R. Anseth K.S. The effect of heparin-functionalized PEG hydrogels on three-dimensional human mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation. Biomaterials. 2007;28:66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flory P. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1953. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D.A. Williams C.G. Li Q. Sharma B. Elisseeff J.H. Synthesis and characterization of a novel degradable phosphate-containing hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3969. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nuttelman C.R. Benoit D.S.W. Tripodi M.C. Anseth K.S. The effect of ethylene glycol methacrylate phosphate in PEG hydrogels on mineralization and viability of encapsulated hMSCs. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1377. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada M. Kadoya Y. Kasai S. Kato K. Mochizuki M. Nishi N. Watanabe N. Kleinman H.K. Yamada Y. Nomizu M. Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV)-containing laminin alpha 1 chain peptides form amyloid-like fibrils. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nomizu M. Kuratomi Y. Malinda K.M. Song S.Y. Miyoshi K. Otaka A. Powell S.K. Hoffman M.P. Kleinman H.K. Yamada Y. Cell binding sequences in mouse laminin alpha 1 chain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tashiro K. Sephel G.C. Weeks B. Sasaki M. Martin G.R. Kleinman H.K. Yamada Y. A synthetic peptide containing the IKVAV sequence from the a-chain of laminin mediates cell attachment, migration, and neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gronthos S. Simmons P.J. Graves S.E. Robey P.G. Integrin-mediated interactions between human bone marrow stromal precursor cells and the extracellular matrix. Bone. 2001;28:174. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrell E. O'Brien F.J. Doyle P. Fischer J. Yannas I. Harley B.A. O'Connell B. Prendergast P.J. Campbell V.A. A collagen-glycosaminoglycan scaffold supports adult rat mesenchymal stem cell differentiation along osteogenic and chondrogenic routes. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:459. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.George J. Kuboki Y. Miyata T. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts on honeycomb collagen scaffolds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;95:404. doi: 10.1002/bit.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ong S.Y. Dai H. Leong K.W. Inducing hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in pellet culture. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4087. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Au A. Boehm C.A. Mayes A.M. Muschler G.F. Griffith L.G. Formation of osteogenic colonies on well-defined adhesion peptides by freshly isolated human marrow cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1847. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cool S.M. Nurcombe V. Substrate induction of osteogenesis from marrow-derived mesenchymal precursors. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:632. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khlusov I.A. Karlov A.V. Sharkeev Y.P. Pichugin V.F. Kolobov Y.P. Shashkina G.A. Ivanov M.B. Legostaeva E.V. Sukhikh G.T. Osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow in situ: role of physicochemical properties of artificial surfaces. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2005;140:144. doi: 10.1007/s10517-005-0431-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klees R.F. Salasznyk R.M. Kingsley K. Williams W.A. Boskey A. Plopper G.E. Laminin-5 induces osteogenic gene expression in human mesenchymal stem cells through an ERK-dependent pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto J. Kariya Y. Miyazaki K. Regulation of proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by laminin-5. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2346. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salasznyk R.M. Klees R.F. Boskey A. Plopper G.E. Activation of FAK is necessary for the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on laminin-5. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:499. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salasznyk R.M. Klees R.F. Williams W.A. Boskey A. Plopper G.E. Focal adhesion kinase signaling pathways regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:22. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]