In 1509, at the age of 18 years, Henry VIII ascended the throne of England and the recent 500th anniversary of this event has prompted a resurgence of interest in his life, politics and health. Henry was a fascinating character: initially blessed with good looks and stature; tremendous sporting prowess; a renaissance scholar revered by his subjects as ‘Bluff King Hal’. However, over the course of his 38-year reign, he underwent a dramatic personal metamorphosis to become a despotic, cruel and tyrannical sovereign, vile of temper and cursed by his deteriorating health and his ‘sorre legge’.1 While the changes in his character undoubtedly mirrored the pressures and political machinations of the day, it is interesting to reflect on the impact that persistent ulceration would have had on his life, personality and political administration. Five hundred years later, with the advent of vascular surgery and a modern understanding of the factors inherent in ulceration, it is also possible to reconsider the underlying aetiology of his leg ulcers.

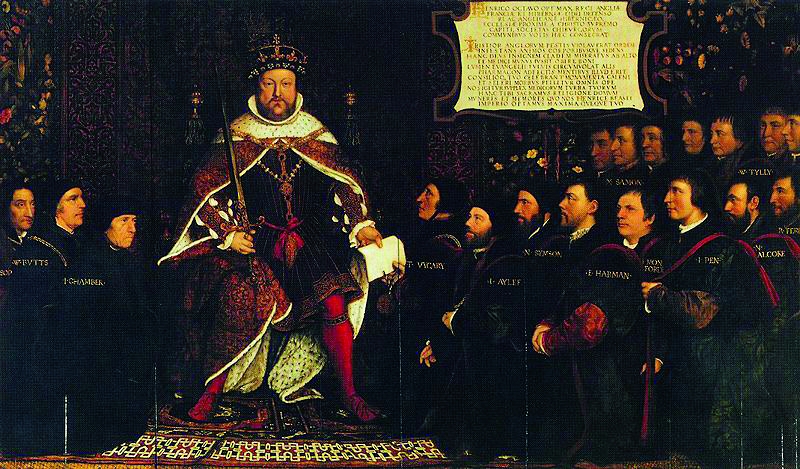

Henry himself was keenly interested in medicine. He founded the Royal College of Physicians in 15182 and amalgamated The Barbers Company of London and the Guild (or Fellowship) of Surgeons to form the Company of Barber-Surgeons3 in 1540 (Figure 1). His administration passed seven separate Acts of Parliament aimed at regulating and licensing medical practitioners, legislature that required no further amendment for 300 years.4 Guided by Sir Thomas More, the Under-Sherriff of London, Henry presided over great improvements in public health; installing public water supplies and sewers, and implementing segregation and crude disinfection during epidemics of plaque and sweating-sickness.5 Henry also personally prepared medicines in the form of salves and ointments from compounds such as ground pearls and white lead for the treatment of his friends and, later, for himself:6 ‘An Oyntment devised by the kinges Majesty made at Westminster. And devised at Grenwich to take away inflammations and to cease payne and heale ulcers called gray plaster.’

Figure 1.

Henry VIII and the Barber-Surgeons. This large work was commissioned from Hans Holbein the Younger to commemorate the grant of a royal charter to the Company of Barbers and the Guild of Surgeons on their merger in 1540. Henry is shown wearing his famous garter around his left calf (although in other portraiture the garter is sometimes seen on the right leg). The importance of Thomas Vicary, himself instrumental in the merger, is indicated by his proximity to the King

The personal medical history of Henry VIII

Henry's medical history is documented, not by his personal physicians or surgeons (most notably Sir William Butts, Thomas Vicary, Dr Chambre, Dr Owen and Dr Clement who either did not keep records – probably for their own safety – or whose case-notes have been lost or destroyed), but within State Papers and contemporaneous letters of the time, particularly the despatches sent from the English Court by foreign ambassadors reporting the state of the King's health to their own governments.1 Much of this information would have been based on pronouncements by the King's physicians and surgeons. Henry enjoyed rude health during his early years, suffering only a bout of smallpox (1514) and occasional malaria, which was endemic in the English marshlands at that time (1521 onwards).1 He was physically fit, described by Giustinian, the Venetian Ambassador to the English Court as: ‘… the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on; above the usual height, with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion very fair and bright with auburn hair combed straight and short in the French fashion, and a round face so very beautiful that it would become a pretty woman, his throat being rather long and thick’.7 Henry's prowess at jousting, tilting, hunting and tennis was legendary: ‘not only very expert in arms, and of great valour, and most excellent in his personal endowments, but … likewise so gifted and adorned with mental accomplishments of every sort that we believe him to have few equals in the world’. However, his propensity for vigorous sport led to a variety of injuries of varying severity. In 1527 Henry injured his left foot playing tennis, and the resultant swelling led him to adopt a single loose black velvet slipper, rapidly prompting a new fashion among his courtiers.8 In the same year Henry was laid up at Canterbury with a ‘sorre legge’, the first record of a wound thought to be an ulcer, possibly on the thigh. Thomas Vicary was summoned to his aid and the ulcer healed, with the King's gratitude earning Vicary the post of sergeant-surgeon and an annual salary of 20 shillings.1

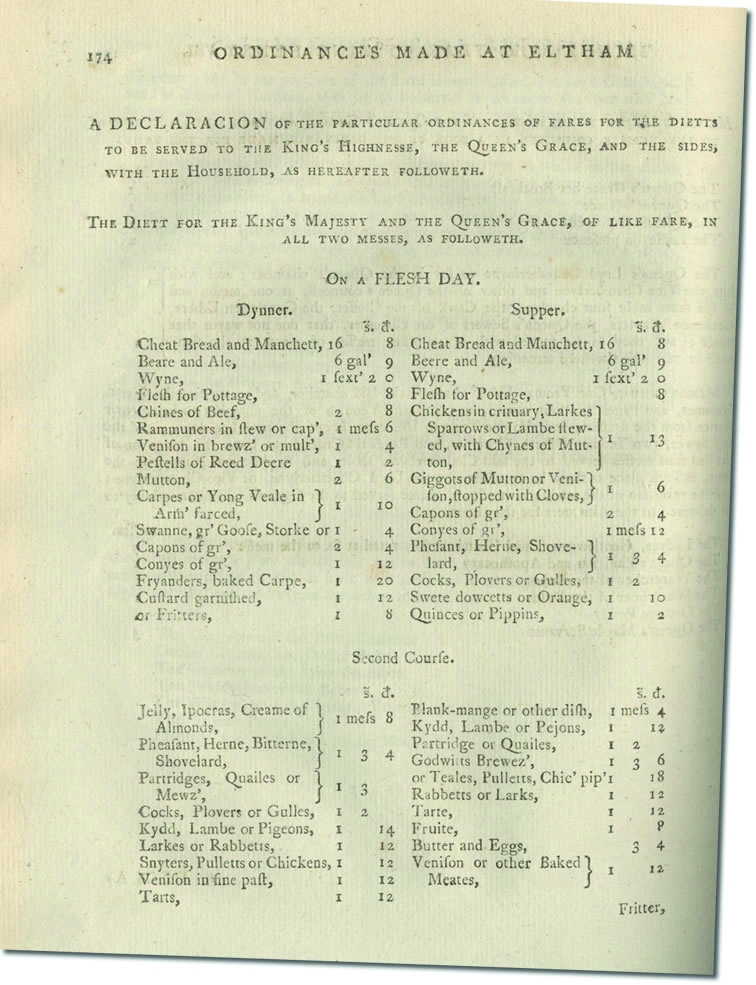

Henry remained relatively healthy throughout the following decade (1527–1536), despite tumultuous religious and political upheaval. The absence of a male heir and the presence of Anne Boleyn, a pretty young consort to the Queen, prompted his break with the Catholic Church in Rome, a divorce from Catherine of Aragon and the dissolution of the monasteries. Henry, the self-appointed head of both the Church and the State was released from any constraints upon his behaviour. Life at court remained one of spectacular excess. A bon-viveur renowned for his appetite, Henry's weight gradually increased despite his early athleticism. In 1526 Henry drew up the Ordinances of Eltham ( Figure 2), a detailed set of instructions as to what he should be served with each day, clearly documenting a massive appetite for meat, pastries and wine. His expanding girth is easily pictured by comparison between his personal suits of armour. Henry was tall at over six feet, and in his 20s weighed about 15 stone with a 32″ waist and 39″ chest but by his 50s his waist had increased to 52″ and, by the time of his death in 1547 at the age of 56 years, he is thought to have weighed about 28 stone ( Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The Ordinances at Eltham. Henry dictated his requirements for the King's table on a ‘flesh’ day

Figure 3.

The King's Armour. Henry's appetite and reduced capacity for exercise took its toll on his waistline. His mounted armour (a) dates from 1515 whereas the later suit (b) was forged around 1540

By the age of 44 years, Henry was already significantly obese, reportedly requiring a hoist in order to mount his horse, but in good enough health to continue with his favourite sporting pursuits. However, in January 1536, while jousting at Greenwich, the King was unseated from his horse, crashing to the ground with the fully-armoured horse landing on top of him. He remained unconscious (‘without speech’) for two hours, a head injury that would certainly have warranted a CT scan to exclude intracranial haemorrhage by the criteria of today. His legs were crushed in the fall and he may have sustained fractures to one or more of his long bones. There was such concern over the potential severity of his injuries that the Queen (Anne Boleyn) is said to have miscarried a male child shortly after hearing of the accident. Several authors attribute a further acute deterioration in Henry's subsequent mood and behaviour to the head injuries sustained in this fall.1,9 He suffered from headaches, and although the wounds Henry sustained to his legs initially healed, ulceration reappeared shortly afterwards, being particularly unpleasant and difficult to manage during 1536–1538. The year of 1536 has been described as an ‘annus horribilis’ for the King:9 his injuries, the loss of his potential heir, the death of his illegitimate son (the Duke of Richmond) and accusations of Anne's adultery made him increasingly unpredictable, irascible and cruel, and prompted him to brutally rid himself of another wife.

By now his ulcers appear to have been bilateral, purulent and seeping, and Henry himself wrote to the Duke of Norfolk, excusing himself from travelling and confessing: ‘to be frank with you, which you must keep to yourself, a humour has fallen into our legs and our physicians advise us not to go far in the heat of the day’. Transient superficial healing of the fistulous communications between abscess cavities and skin inevitably led to episodes of sepsis and bouts of fever: ‘and for ten to twelve days the humours which had no outlet were like to have stifled him, so that he was sometime without speaking, black in the face and in great danger’ (Castillon to Montmorency from the English Court). Henry's physicians attempted to keep these fistulae open to allow drainage of the ‘humours’, often lancing the ulcers with red-hot pokers; a therapy unlikely to have improved the King's ill-temper. Courtiers and ambassadors alike were aware of the King's problems. Witnesses called at the 1537 trial of the Marquis of Exeter and Lord Montagu (who were accused of treason and plotting to replace Henry with a Yorkist monarch) alleged that the traitors had disrespectfully discussed Henry's health saying of the King: ‘he has a sorre legge that no pore man would be glad off, and that he should not lyve long for all his auctoryte next God’ and ‘he will die suddenly, his legge will kill him, and then we shall have jolly stirring’. After such treacherous sentiments both men were, unsurprisingly, beheaded. Execution for treason (by hanging, eviscerating, beheading, burning at the stake or boiling alive) had become increasingly commonplace in the latter part of Henry's reign. This king was responsible for more deaths than any monarch before or since. In a brutal age, Henry was known and feared for his cruelty. Indeed, in 1558, a French physician commenting upon the fate meted out to those who had aroused the King's wrath wrote: ‘in this country you will not meet with any great nobles whose relations have not had their heads cut off …’.

Henry's legs remained persistently and badly ulcerated, but his overwhelming desire was to safeguard the succession of the Tudor dynasty and the stench did not curtail his quest for an heir. His spirits were eventually buoyed by the birth of his son, Edward VI, and then dashed by the death of his wife, Jane Seymour, 12 days later from puerperal sepsis. Two further marriages followed in quick succession; a political match with the plain Anne of Cleves and a fateful liason with the pretty young Katherine Howard. Both were rapidly despatched, Anne divorced to the country and Katherine to the Tower. Despite his ulcerated legs and ignoring the advice of his physicians to rest, fearful of a rumoured alliance between Rome, France and Spain with the threat of invasion, Henry personally travelled to the coast to oversee fortification of the harbours, often spending many hours on horseback. His ulcers failed to heal and in March 1541 he was again laid low with fever: ‘one of his legs, formerly opened and kept open to maintain his health, suddenly closed to his great alarm, for, five or six years ago, in the like case, he thought to have died. This time prompt remedy was applied and he is now well and the fever gone’ (Marillac, French Ambassador from the English Court). Now unable to take any exercise at all, and refusing to curb his daily intake, Henry's weight climbed steadily: ‘the King is very stout and marvellously excessive in eating and drinking, so that people worth credit say he is often of a different opinion in the morning than after dinner’. His marriage in 1543 to the kindly Katherine Parr has been interpreted by some as acquiring a convenient nursemaid in the final years of his life. His legs deteriorated further and the stench from his infected ulcers could be identified three rooms away, often heralding the monarch's arrival. He was in constant pain but Henry, ever mindful of the threats facing England from her immediate neighbour, France, refused to rest, extensively visiting ports and cities around his kingdom and even personally travelling to wage war overseas at the Battle of Boulogne. His sudden and terrible rages would send his courtiers fleeing and none but his wife could calm him. By 1546, his activities had been seriously limited although he continued to travel to his estates in the south of England and even to hunt in between periods of ill-health, refusing to rest despite the advice of his physicians. Towards the end of this year Henry was forced to return to Westminster and, unable to walk due to his grossly swollen legs and morbid obesity, he was carried around his palace in a chair. Further bouts of fever and cautery to his leg ulcers followed and he deteriorated rapidly, dying in the early hours of 28 January 1547.

The aetiology of Henry's ulceration

As a young man, Henry was inordinately proud of his fine calves, displaying them by use of a garter fastened around his leg just below the knee (Figure 1). The same legs were to torture him for the last two decades of his life, described by Chapuys, the Spanish Ambassador as: ‘… the worst legs in the world’. The aetiology of the King's ulceration may encompass a range of different potential diagnoses, making Henry an interesting and educational case study. The first reports of the King's ulcer refer to an area on the thigh when Henry was still a relatively young man. Many authors have attributed this to the chancre of primary syphilis but there is little evidence to support this diagnosis. Tudor physicians were familiar with syphilis, ‘the great pox’, and treated Treponema pallidum infection with mercury10 until ‘the gums were sore and the saliva [one of the four ‘humours’ described by Galen whose works were translated by Henry's physician Thomas Linacre, and on whose teaching Tudor medicine was still firmly anchored11] ran freely’. There is no evidence that Henry was ever treated for syphilis and his apothecaries' accounts do not record any purchases of mercury.1 Neither Henry nor his wives developed any other manifestations of untreated secondary or tertiary syphilis. Henry was a great sportsman in his youth and no stranger to the injuries that accompanied the joust or the tilt and it is possible that this lesion represents an infected wound, slow to heal.

Subsequent ulceration affected Henry's legs bilaterally below the knee and may have been due to venous disease. The wearing of a garter (Figure 1) and the references to the King's shapely calf make it unlikely that Henry had prominent primary varicose veins. However, he may have acquired venous hypertension as a result of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). History does not record how tightly the garter was bound around his upper calf and he had several injuries to his legs as a result of his sporting activities, both of which represent risk factors for DVT. The most severe injuries were sustained during the fall from his horse that rendered him unconscious and crushed his legs in 1536. Crush injury with or without associated fracture of one or more long bones with obesity and relative immobility would increase the risk of DVT,12 damage to the deep venous system and subsequent venous insufficiency.13 Severe venous hypertension may therefore have resulted in ulceration. An untreated compound fracture may also result in diffuse infection with cellulitis, osteomyelitis, deep abscess formation and a persistently discharging sinus.14 A compound fracture may well have rendered Henry unable to walk and such a suggestion is absent in the records of the time. It is therefore much more likely that Henry suffered an extensive DVT as a result of his injuries and subsequent immobility resulting in the classical pattern of venous ulceration.

As Henry's weight increased and he became morbidly obese, his risk of hypertension and Type II diabetes must also have been high. His doctors repeatedly exhorted him to reduce his tremendous consumption of meat and wine, his penchant for high cholesterol foodstuffs clearly documented in the Ordinances of Eltham (Figure 2). Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and Type II diabetes are known to accelerate peripheral vascular disease and, more recently, abdominal obesity has been identified as a marker of arterial insufficiency.15 The onset of peripheral vascular disease would seriously exacerbate venous ulceration, reducing the capacity for healing and causing difficulties in the fight against distal infection. Additionally, the grossly swollen legs that Henry suffered towards the end of his life may represent congestive cardiac failure in an arteriopath.16 Clearly, we are unlikely ever now to know the truth.

Persistent chronic leg ulcers have been shown to seriously adversely affect quality of life even in the age of modern medical treatment and analgesia.17 For Henry, racked with pain and repetitive infection, his ulcers regularly cauterized with red-hot irons, the situation must have been intolerable. The effect of chronic pain on the temperament is well recognized and the actions of many a historical figure have been linked to their personal physical misery. Judge Jeffries (1645–1689), widely known as the ‘Hanging Judge’ for his merciless punishment of King James II's enemies after the Monmouth Rebellion, was reputed to be in such a foul temper because of the bladder stones bouncing up and down on his trigone while travelling to the Bloody Assizes in a poorly-sprung carriage over potholed roads;18 and Napoleon Bonaparte's painful haemorrhoids left him sullen and quick to anger, unable to survey his troops by horseback at the Battle of Waterloo.19 Henry's vile temper was undoubtedly influenced by his clinical situation. Although he did not bear his suffering with fortitude, and his latter years were characterized by frequent tempestuous rages and cruelty, viciously turning on those that he had once patronised, he was courageous in his refusal to lie a-bed, allowing a fleeting glimpse of the valiant prince he used to be.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding None

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor CRC

Contributorship The idea for this paper was conceived by EJC and researched and executed by CRC. Both authors were involved in manuscript preparation

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank David Starkey for his helpful comments on this subject

References

- 1.MacNalty AS. Henry VIII: A Difficult Patient. London: Christopher Johnson Publishers; 1952 [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Roll of the Royal College of Physicians. See http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/history-heritage/College-history-new/Munks%20Roll/Pages/Munks-Roll.aspx .

- 3.Bagwell CE. “Respectful image”: revenge of the barber surgeon. Ann Surg 2005;241:872–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes JT. The licensing of medical practitioners in Tudor England: legislation enacted by Henry VIII. Vesalius 2006;12:4–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacNalty AS. Sir Thomas More as a public health reformer. Nature 1946;158:732–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starkey D, Doran S, eds. Henry VIII: Man and Monarch. London: British Library Publishing; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giustinian S. Four Years at the Court of Henry VIII. London: Smith, Elder & Co.; 1854 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayward M. Dress at the Court of Henry VIII. London: Maney Publishing; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipscombe S. Who was Henry VIII? History Today 2009;59:14–20 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane Furdell E. The Royal Doctors, 1485–1714: medical personnel at the Tudor and Stuart courts. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron R. Thomas Linacre at the portal to scientific medicine. BMJ 1964;2:589–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knudson M, Ikossi D, Khaw L, et al. Thromboembolism after trauma: an analysis of 1602 episodes from the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank. Ann Surg 2004;240:490–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prandoni P, Khan S. Post-thrombotic syndrome: prevalence, prognostication and need for progress. Br J Haematol 2009;145:286–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zalavras C, Marcus R, Levin L, et al. Management of open fractures and subsequent complications. Instr Course Lect 2008;57:51–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu B, Zhou J, Waring M, et al. Abdominal obesity and peripheral vascular disease in men and women: A comparison of waist-to-thigh ratio and waist circumference as measures of abdominal obesity. Atherosclerosis 2009, Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keynes M. The personality and health of King Henry VIII (1491–1547). J Med Biogr 2005;13:174–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herber O, Schnepp W, Reiger M. A systematic review on the impact of leg ulceration on patients' quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;25:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kemble J. Idols and Invalids. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc.; 1936 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welling D, Wolff B, Dozois R. Piles of defeat. Napoleon at Waterloo. Dis Colon Rectum 1988;31:303–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]