Abstract

Background

The shikimate pathway is an attractive target for the development of antitubercular agents because it is essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, but absent in humans. M. tuberculosis aroE-encoded shikimate dehydrogenase catalyzes the forth reaction in the shikimate pathway. Structural and functional studies indicate that Lysine69 may be involved in catalysis and/or substrate binding in M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase. Investigation of the kinetic properties of mutant enzymes can bring important insights about the role of amino acid residues for M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase.

Findings

We have performed site-directed mutagenesis, steady-state kinetics, equilibrium binding measurements and molecular modeling for both the wild-type M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase and the K69A mutant enzymes. The apparent steady-state kinetic parameters for the M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase were determined; the catalytic constant value for the wild-type enzyme (50 s-1) is 68-fold larger than that for the mutant K69A (0.73 s-1). There was a modest increase in the Michaelis-Menten constant for DHS (K69A = 76 μM; wild-type = 29 μM) and NADPH (K69A = 30 μM; wild-type = 11 μM). The equilibrium dissociation constants for wild-type and K69A mutant enzymes are 32 (± 4) μM and 134 (± 21), respectively.

Conclusion

Our results show that the residue Lysine69 plays a catalytic role and is not involved in substrate binding for the M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase. These efforts on M. tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase catalytic mechanism determination should help the rational design of specific inhibitors, aiming at the development of antitubercular drugs.

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health concern. It has been estimated that one-third of the world population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of TB, and that 30 million people died from this disease in the last decade [1]. The epidemic of the human immunodeficiency virus, the increase in the homeless population, and the decline in health care structures and national surveillance are contributing factors to TB resurgence. Inappropriate treatment regimens and patient noncompliance in completing the therapies are associated with the emergence of multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB), defined as strains of M. tuberculosis resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, two pivotal drugs used in the standard treatment of TB [2]. It has been reported the emergence of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB cases, defined as cases in persons with TB whose isolates are MDR as well as resistant to any one of the fluoroquinolone drugs and to at least one of the three injectable second-line drugs [3]. XDR-TB is widespread raising the prospect of virtually incurable TB worldwide [3]. There is thus an urgent need for new drugs to improve the treatment of MDR- and XDR-TB, and to provide more effective drugs to shorten the duration of TB treatment. Enzyme inhibitors make up roughly 25% of the drugs marketed [4], and are thus important promising drug targets.

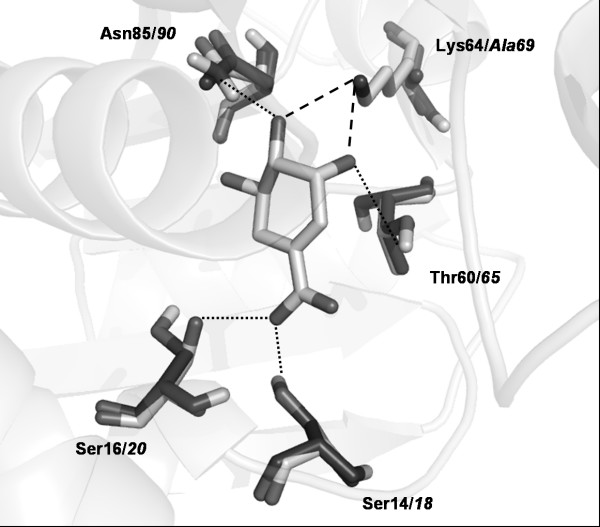

The shikimate pathway is an attractive target for the development of herbicides and antimicrobial agents because it is essential in algae, higher plants, bacteria, and fungi, but absent from mammals [5]. The mycobacterial shikimate pathway leads to the biosynthesis of precursors of aromatic amino acids, naphthoquinones, menaquinones, and mycobactins [6], and is essential for M. tuberculosis viability [7]. Shikimate dehydrogenase (SD; EC 1.1.1.25), the fourth enzyme of this pathway, catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of 3-dehydroshikimate (DHS) to shikimate (SHK, Fig. 1). We have previously reported production, characterization, and determination of kinetic and chemical mechanisms of aroE-encoded SD from M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain (MtbSD) [8-10]. Multiple sequence alignment, comparative homology modeling, and pH-rate profiles suggested that the Lysine69 in the DHS/SHK binding site of MtbSD plays a role in substrate binding and/or catalysis [10,11]. Here we describe site-directed mutagenesis, steady-state kinetics, fluorimetric measurements and structural analyses to probe the role of Lys69 in MtbSD and provide insight into the molecular basis of DHS/SHK recognition and/or catalysis.

Figure 1.

The shikimate dehydrogenase-catalyzed reaction.

Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis

A previously constructed pET-23a(+)::aroE recombinant vector [8] was used as a template for PCR-based mutagenesis using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The synthetic oligonucleotides employed were as follows: 5'-ggtgtttcggtgaccatgccgggcgcgttcgccgccctgcggttcg-3' (forward) and 5'-cgaaccgcagggcggcgaacgcgcccggcatggtcaccgaaacacc-3' (reverse) (in bold is the codon for alanine). PfuTurbo® DNA polymerase and standard PCR amplification program were employed. The PCR product was treated with DpnI endonuclease that specifically digests the methylated DNA template, and selects for the mutation-containing synthesized DNA.

Expression, release and purification of recombinant MtbSD

The recombinant plasmid was introduced into E. coli C41 (DE3) host cells (Novagen, Madison, WI) by electroporation. Single colonies were used to inoculate 2 L of LB medium containing 50 μg mL-1 ampicillin, and 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added to cultures reaching an OD600 of 0.4 - 0.6, and grown for 24 h at 37°C at 180 rpm. Cells (5 g) were harvested by centrifugation at 14,900 g for 30 min at 4°C, and stored at -20°C. The freeze-thaw method was used to release the proteins in the soluble fraction [8]. The purification protocol was as previously described [12]. Samples of the purification steps were analyzed by SDS-PAGE [13] and protein content by the Bradford's method [14].

Enzyme activity assays and determination of kinetic parameters

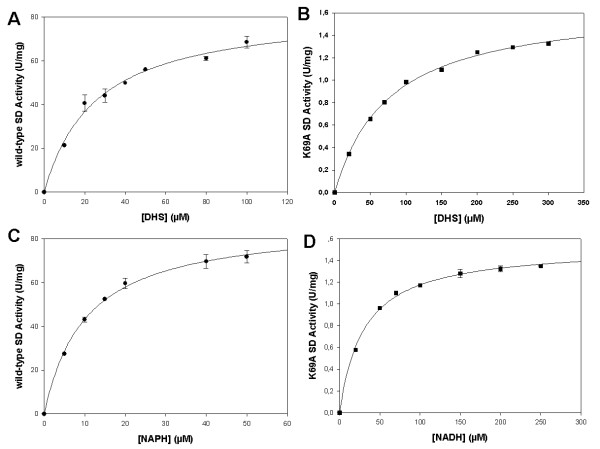

Steady-state kinetics measurements of homogeneous MtbSD K69A mutant activity were carried out for the forward direction at 25°C in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (ε = 6220 M-1 cm-1 for NADPH) accompanying the conversion of NADPH and DHS to NADP+ and SHK. The K69A activity was measured at varying final concentrations of DHS (20-300 μM) and NADPH at constant saturating level (200 μM); and varying NADPH concentrations (20-250 μM) and DHS at constant saturating level (250 μM; Fig. 2B and 2D). The wild-type SD activity was measured at various DHS concentrations (10-100 μM) and NADPH at constant saturating level (200 μM); and various NADPH concentrations (5-50 μM) and DHS at constant saturating level (250 μM; Fig. 2A and 2C). All measurements were in duplicate. Steady-state kinetic constants were obtained by non-linear regression analysis of the kinetic data fitted to the the Michaelis-Menten equation (v = Vmax × [S]/Km + [S]) using the SigmaPlot software (SPSS, Inc).

Figure 2.

Steady-state kinetic measurements for wild-type (A and C) and K69A (B and D) MtbSD in the forward direction. A and B: DHS concentrations were varied while NADPH concentration was maintained at a fixed saturating level. C and D: NADPH concentrations were varied while DHS concentration was maintained at a fixed saturating level.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence titration was performed in a Shimadzu spectrofluorophotometer RF-5301PC at 25°C by making microliter additions of DHS substrate stock solutions to 2 mL of 1 μM of MtbSD in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.3. The binding of DHS to MtbSD causes a quench in the intrinsic protein fluorescence (λexc = 300 nm; 310 ≤ λem ≤ 450 nm; maximum λem at 340 nm), which allowed monitoring of MtbSD-DHS binary complex formation at equilibrium. To assess the DHS inner-filter effect in the fluorimeter, two cuvettes were placed in series so that the contents of the first cuvette acted as a filter of the excitation light and the light emitted from the second cuvette detected. DHS was added to the first cuvette, while the second cuvette contained the protein. In this manner, DHS inner-filter effect on protein fluorescence could be assessed. The results were plotted to a rectangular hyperbola by using the nonlinear regression function of SigmaPlot 2004 (SPSS, Inc.).

MtbSD K69A structural analysis

The wild-type MtbSD three-dimensional (3D) model was built previously by comparative homology modeling using Escherichia coli SD as template (PDB ID: 1NYT) [10], however, a more recent 3D structure for Thermus thermophilus SD (PDB ID: 2EV9), solved by X-ray crystallography at 1.90 Å in complex with shikimate [15], was used as a template for MtbSD K69A mutant modeling, as well as to evaluate DHS/SHK substrate binding mode to MtbSD. T. thermophilus SD shows higher primary structure identity to MtbSD (~30% identity and 13% strong similarity) than E. coli SD (26% identity and 15% strong similarity), and the presence of both enzyme's cofactor and substrate bound at its active site makes such structure a more suitable template for MtbSD comparative homology modeling.

Target and template pair-wise sequence alignment required small gaps inclusion on both M. tuberculosis and T. thermophilus SD primary sequences. MtbSD K69A model was built by restrained-based homology modeling implemented in MODELLER9v1 [16], with the standard protocol of the comparative protein structure modeling methodology, by satisfaction of spatial restrains [17,18]. Atomic coordinates of SHK heteroatoms were copied from template structure into the MtbSD K69A model. The best model was selected according to MODELLER objective function [19] and subjected to energy minimization for amino acid side chain and main chain rearrangements with GROMACS package [20] using the 43a1 force-field. The system was submitted to an initial steepest descent energy minimization in vacuo with a maximum number of 400 minimization steps, followed by a maximum of 3000 steps of conjugate gradient energy minimization.

The program PROCHECK and VERIFY 3D were employed to, respectively, analyze stereochemical quality and validate the 3D profile of the model, as previously described [10]. Structural correspondence between MtbSD K69A model and T. thermophilus was evaluated by their root-mean square deviation (RMSD). H-bond interactions were evaluated with LIGPLOT v4.4.2 [21], considering an atomic distance cut off of 3.9 Å (program default values).

Findings and Discussion

Site-directed mutagenesis, protein expression and purification

Total sequencing of aroE mutant DNA into pET-23a(+) vector confirmed that the mutation was introduced into the expected site and that no unwanted mutations were introduced by the PCR amplification step. The recombinant MtbSD protein purification protocol resulted in a protein yield of 13%, according to the previous protocol [12].

Steady-state kinetic parameters

The apparent steady-state kinetic parameters for K69A (Fig. 2B and 2D) and wild-type MtbSD (Fig. 2A and 2C) are given in Table 1. It is noteworthy that the catalytic constant (kcat) value for wild-type MtbSD (50 s-1) is 68-fold larger than K69A (0.73 s-1), whereas there was a modest increase in the Km values for DHS (K69A = 76 μM; wild-type MtbSD = 29 μM) and NADPH (K69A = 30 μM; wild-type MtbSD = 11 μM). The apparent second-order rate constant (kcat/Km) values for DHS (K69A = 9.6 × 103 M-1s-1; wild-type MtbSD = 1.7 × 106 M-1s-1) and NADPH (K69A = 24 × 103 M-1s-1; wild-type MtbSD = 4.5 × 106 M-1s-1) indicate that the mutant has a lower specificity constant for both substrates. A comparison of kcat/Km values is an appropriate method to assess the effect(s) of a mutation on substrate(s) binding and catalysis since it includes the activation energies and the binding energies [22]. A change of 12.8 kJ mol-1 can be calculated when we compare the values of kcat/Km of DHS reduction for wild-type and K69A MtbSD. These results indicate that the conserved Lys69 residue in MtbSD plays a critical role in catalysis, but plays no role in substrate binding. Moreover, the fact that the K69A MtbSD mutant protein still binds DHS and NADPH with only slightly larger Km values as compared to wild-type enzyme indicates that the mutant protein is properly folded giving more confidence that the results are not an artifact generated by the mutation. Linearity of each measurement and dose dependence when adding different volumes of the enzyme solution were confirmed for all enzyme activity assays (data not shown).

Table 1.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters and equilibrium binding constants for wild type and K69A mutant MtbSD

| Parameter | Wild-type | K69A |

|---|---|---|

| Vmax (U mg-1)a | 110 ± 2 | 1.61 ± 0.03 |

| Km DHS (μM)a | 29 ± 2 | 76 ± 4 |

| Km NADPH (μM)a | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 30 ± 2 |

| kcat (s-1)a | 50 ± 1 | 0.73 ± 0.01 |

| kcat/Km DHS (M-1 s-1)a | 1.7 (± 0.1) × 106 | 9.6 (± 0.5) × 103 |

| kcat/Km NADPH (M-1 s-1)a | 4.5 (± 0.2) × 106 | 24 (± 2) × 103 |

| Kd DHS (μM)b | 32 ± 4 | 134 ± 21 |

a steady-state kinetic parameters

b spectroscopic measurements of intrinsic protein fluorescence (equilibrium binding)

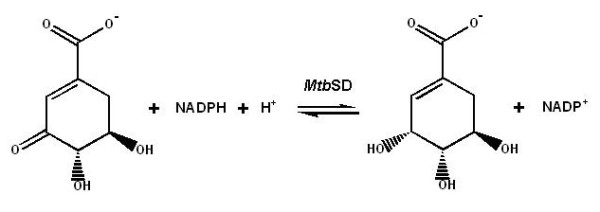

Equilibrium binding

Spectrofluorimetric assays were carried out to determine the equilibrium dissociation constant for MtbSD-DHS binary complex formation (Fig. 3). The change in the intrinsic protein fluorescence at varying DHS concentrations (2-450 μM) yielded equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) values of 32 (± 4) μM for wild-type MtbSD and 134 (± 21) μM for K69A mutant (Table 1). Interestingly, measurements of changes in nucleotide fluorescence upon NADPH binding to wild-type MtbSD (λexc = 370 nm; 380 ≤ λem ≤ 600 nm; maximum λem at 445 nm) did not show any saturation, which indicates a very large Kd value. This is consistent with a steady-state ordered bi-bi mechanism with DHS binding first followed by NADPH binding to MtbSD active site [10]. Moreover, these experiments confirmed our proposal that the Lys69 residue plays a minor role, if any, in substrate binding.

Figure 3.

Spectroscopic measurements of intrinsic protein fluorescence for wild-type (black circles) and K69A (black squares) MtbSD upon DHS binding at varying concentrations.

Structural analysis

Two crystallographic structures of SD in complex with both its coenzyme and SHK (Aquifex aeolicus, PDB ID: 2HK9[23] and T. thermophilus, PDB ID: 2EV9[15], solved by X-ray diffraction at 2.20 Å and 1.90 Å resolution, respectively) are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). T. thermophilus SD structure was chosen as template for comparative homology modeling of MtbSD K69A and for SHK binding analysis because of larger primary sequence identity to MtbSD (~30% identity and 13% strong similarity) as compared to A. aeolicus (24% identity and 16% strong similarity), and lower requirement for inclusion of gaps in primary sequence comparisons.

Analysis of the 3D structures of SDs in complex with NADP+ and SHK suggest that Lys64 in T. termophilus [15] and Lys70 in A. aeolicus [23] interact with C3 of DHS and act as an acid-base catalytic group. Corresponding Lys residue is also suggested to be catalytically active in Staphylococcus epidermidis [24], Haemophilus influenzae [25] and Arabidopsis thaliana [26] SDs.

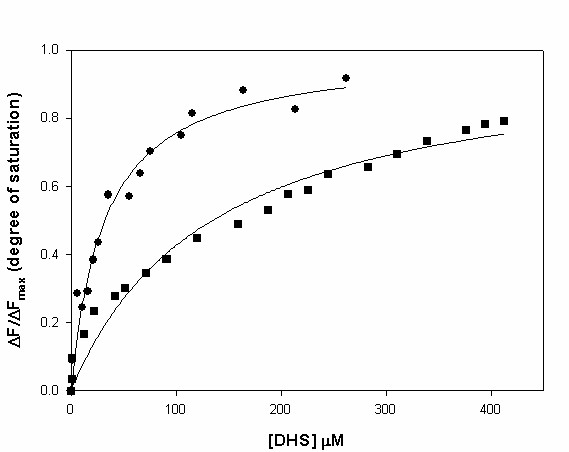

No significant changes were observed on protein's overall tertiary structure and in DHS/SHK binding site after energy minimization of the MtbSD K69A model. The RMSD deviation from template of only 0.55 Å, 99% of amino acids within allowed regions of the Ramachandran's plots and PROCHECK parameters indicate that the K69A model satisfies all stereochemical requirements. Considering only substrate binding site amino acids, MtbSD K69A RMSD values reduced to 0.12 Å when compared to template. Such minor structural variations indicate a strong conservation of the amino acid arrangement at the enzyme's substrate binding site, not only at their α-carbon position but also in regard to their χ rotational angles, where only MtbSD residue Ser20 (Ser16 on template) shows variation on its rotational angle χ1 (2.02 Å for Oγ atom), although not affecting H-bonding to SHK. (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

MtbSD K69A model superimposed on experimentally solved T. thermophilus SD structure. Amino acid side chains involved in SHK binding and SHK molecule are shown as sticks. T. thermophilus and MtbSD K69A amino acids are colored, respectively, in light gray (residue number in bold) and dark gray (residue number in italics). H-bonds are shown as dotted lines; dashed lines represent H-bonds between Lys64/69, missing in MtbSD K69A model.

H-bonding pattern between MtbSD and SHK

LIGPLOT analysis showed that the pattern of H-bonding to SHK is conserved in T. thermophilus SD and MtbSD K69A (Table 2). Gln243 residue in M. tuberculosis (corresponding to Gln235 in T. thermophilus SD) also makes a hydrophobic contact to C5 of SHK, as observed on template's structure. No significant amino acid rearrangements were observed for MtbSD K69A. Not surprisingly, the noticeable change is the loss of two H-bonds with the SHK molecule in K69A mutant. It could be argued that the loss of two H-bonds in K69A MtbSD mutant would demonstrate the role of Lys69 in DHS/SHK binding. The energies of hydrogen bonds have been variously estimated to be between 12 and 38 kJ mol-1 [22]. Spectrofluorimetric measurements showed a reduction of 3.5 kJ mol-1 in binding energy of DHS to K69A MtbSD as compared to the wild-type enzyme.

Table 2.

Hydrogen bonding pattern of SD enzyme and SHK substrate. T. thermophilus values are shown in bold, MtbSD K69A corresponding values are shown in italics.

| SD residue | SD Atom | SHK atom | H bond distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ser14/Ser18 | Oγ | O2 | 2.62/2.55 |

| Ser16/Ser20 | Oγ | O2 | 2.72/2.73 |

| Thr60/Thr65 | Oγ 1 | O11 | 3.28/3.22 |

| Lys64/Lys69 | Nζ | O11 | 2.80/-- |

| Lys64/Lys69 | Nζ | O12 | 3.10/-- |

| Asn85/Asn90 | Nδ 2 | O12 | 3.15/2.93 |

Atom numbering as [24]*.

* O2 corresponds to carboxyl negative oxygen atom, O11 to hydroxyl oxygen bound to C3, O12 to hydroxyl oxygen bound to C4, and O7 to hydroxyl oxygen bound to C5, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

Based on double isotope effects and pH-rate profiles, we have previously proposed that the chemical mechanism for MtbSD involves hydride transfer and solvent proton transfer in a concerted manner, and that an amino acid residue with an apparent pKa value of 8.9 is involved in catalysis [10]. Here we demonstrate that the MtbSD Lys69 is important for catalysis and is likely involved in stabilization of the developing negative charge at the hydride-accepting C-3 carbonyl oxygen of DHS for the forward reaction, acting as an acid-base catalytic group that donates a proton to DHS carbonyl group during reduction, playing a minor role, if any, in substrate binding.

In bacteria, four subclasses of SD have been identified, distinguished by their phylogeny and biochemical activity [27]. In agreement with our results, mutagenesis studies showed that the corresponding residues Lys67 in Haemophilus influenzae SD [25] and Lys385 in Arabidopsis thaliana dehydroquinate dehydratase-SD [26] play a critical role in catalysis and no role in substrate binding. Interestingly, site-directed mutagenesis of Escherichia coli YdiB (a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the reversible reductions of 3-dehydroquinate to quinate and 3-dehydroshikimate to shikimate using as co-substrate either NADH or NADPH) has shown that the conserved Lys71 residue plays a primary role in substrate binding in the Michaelis complex and, although it contributes to some extent to transition state stabilization, plays no essential role in catalysis [28].

It should be pointed out that mechanistic analysis should always be a top priority for new enzyme-targeted drug programs since effective enzyme inhibitors take advantage of enzyme chemistry to achieve inhibition [29]. Accordingly, we hope that the results here presented will pave the way for the target-based rational design of novel effective antitubercular agents. The design of inhibitors of MtbSD enzyme activity may contemplate derivatization of C-3 of DHS with functional groups that make strong interactions with the Lys69 side chain. It would appear to be unlikely that a mutation of Lys69 residue would be selected for to afford drug resistance because here is shown that this amino acid residue plays a critical role in MtbSD enzyme activity. However, an important additional point to be considered when selecting a particular enzyme as a successful drug target is to determine a flux control coefficient, which measures the sensitivity of flux to a change in enzyme concentration. An enzyme is likely a good target if the flux control coefficient is high, whereas it is less likely a good target if the flux control coefficient is close to zero (virtually all the activity must be eliminated by an inhibitor to have the desired chemotherapeutic effect). Bifunctional dehydroquinate dehydratase-shikimate dehydrogenases in plants are responsible for preferential routing of carbon to aromatic amino acid synthesis [30]. However, how shikimate dehydrogenase affects the shikimate pathway flux in M. tuberculosis is still unknown. Therefore, strategies for drug design contemplating derivatization of C-3 of DHS should also take into account whether shikimate dehydrogenase has a low flux control coefficient because mutation of Lys69 would be one way of gaining resistance to this enzyme's inhibitors.

List of abbreviations used

TB: tuberculosis; MDR: multi-drug resistant; XDR: extensively drug-resistant; MtbSD: shikimate dehydrogenase from M. tuberculosis; DHS: 3-dehydroshikimate; SHK: shikimate; Km: Michaelis-Menten constant; RMSD: root-mean square deviation; kcat: catalytic constant; Kd: equilibrium dissociation constant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

VSRJ performed most of the experiments and drafted the manuscript. AB performed the structural analysis and helped to write the manuscript. The study was conceived and coordinated by DSS and LAB, who have also helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Valnês S Rodrigues, Junior, Email: valnesjunior@yahoo.com.br.

Ardala Breda, Email: ardalabreda@hotmail.com.

Diógenes S Santos, Email: diogenes@pucrs.br.

Luiz A Basso, Email: luiz.basso@pucrs.br.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Science and Technology on Tuberculosis (Decit/SCTIE/MS-MCT-CNPq-FNDCT-CAPES) and Millennium Initiative Program (CNPq), Brazil, to D.S.S. and L.A.B. D.S.S. and L.A.B. also acknowledge grants awarded by FINEP. D.S.S. (304051/1975-06) and L.A.B. (520182/99-5) are research career awardees from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil (CNPq). We are grateful to Professor John W. Frost, Department of Chemistry of Michigan State University, for his generous gift of 3-dehydroshikimate.

References

- Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso LA, Blanchard JS. Resistance to antitubercular drugs. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;456:115–144. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4897-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman SE, Chaisson RE. From magic bullets back to the Magic Mountain: the rise of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:295–298. doi: 10.1038/nm0307-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JG. Mechanistic basis of enzyme-targeted drugs. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5561–5571. doi: 10.1021/bi050247e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley R. The shikimate pathway - a metabolic tree with many branches. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25:307–384. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducati RG, Basso LA, Santos DS. Mycobacterial shikimate pathway enzymes as targets for drug design. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:423–435. doi: 10.2174/138945007780059004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish T, Stoker NG. The common aromatic amino acid biosynthesis pathway is essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3069–3077. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães MLB, Pereira CP, Basso LA, Santos DS. Cloning and expression of functional shikimate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.25) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Prot Expr Purif. 2002;26:59–64. doi: 10.1016/S1046-5928(02)00509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca IO, Magalhães MLB, Oliveira JS, Silva RG, Mendes MA, Palma MS, Santos DS, Basso LA. Functional shikimate dehydrogenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: purification and characterization. Prot Expr Purif. 2006;46:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca IO, Silva RG, Fernandes CL, de Souza ON, Basso LA, Santos DS. Kinetic and chemical mechanisms of shikimate dehydrogenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;457:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri HA, Borges JC, Fonseca IO, Pereira JH, Neto JR, Basso LA, Santos DS, de Azevedo WF Jr. Structural studies of shikimate 5-dehydrogenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteins. 2008;72:720–730. doi: 10.1002/prot.21953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Junior VS, Basso LA, Santos DS. Homogeneous recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis shikimate dehydrogenase production: an essential step towards target-based drug design. Int J Biol Macromol. 2009;45:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM, McRorie RA, Williams WL. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagautdinov B, Kunishima N. Crystal structures of shikimate dehydrogenase AroE from Thermus thermophilus HB8 and its cofactor and substrate complexes: insights into the enzymatic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:424–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A, Blundell TL. Comparative Protein Modelling by Satisfaction of Spatial Restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sánchez R, Melo F, Šali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling of Genes and Genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A, Overington JP. Derivation of rules for comparative protein modelling from a database of protein structure alignments - Modeling mutations and homologous proteins. Protein Science. 1994;3:1582–1596. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen MY, Šali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Protein Science. 2006;15:2507–2524. doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoel D van der, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comp Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Prot Eng. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. first. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gan J, Wu Y, Prabakaran P, Gu Y, Li Y, Andrykovitch M, Liu H, Gong Y, Yan H, Ji X. Structural and biochemical analyses of shikimate dehydrogenase AroE from Aquiflex aeolicus: implications for the catalytic mechanism. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9513–9522. doi: 10.1021/bi602601e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Hu T, Wu D, Qu S, Zhou J, Ding J, Shen X, Qu D, Jiang H. X-ray crystallographic and enzymatic analyses of shikimate dehydrogenases from Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEBS J. 2009;276:1125–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Korolev S, Koroleva O, Zarembinski T, Collart F, Joachimiak A, Christendat D. Crystal structure of a novel shikimate dehydrogenase from Haemophilus influenzae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17101–17108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412753200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SA, Christendat D. Structure of Arabidopsis dehydroquinate dehydratase-shikimate dehydrogenase and implications for metabolic channeling in the shikimate pathway. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7787–7796. doi: 10.1021/bi060366+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Stavrinides J, Christendat D, Guttman DS. A phylogenomic analysis of the shikimate dehydrogenases reveals broadscale functional diversification and identifies one functionally distinct subclass. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:2221–2232. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner HA, Nadeau G, Matte A, Michel G, Ménard R, Cygler M. Site-directed mutagenesis of the active site region in the quinate/shikimate 5-dehydrogenase YdiB of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7162–7169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JG. Enzymes as a special class of therapeutic target: clinical drugs and modes of action. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. Bifunctional and moonlighting enzymes: lighting the way to regulatory control. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]