Abstract

Neural stem cells (NSCs) lie at the heart of central nervous system development and repair, and deficiency or dysregulation of NSCs or their progeny can have significant consequences at any stage of life. Immune signaling is emerging as one of the influential variables that define resident NSC behavior. Perturbations in local immune signaling accompany virtually every injury or disease state and signaling cascades that mediate immune activation, resolution, or chronic persistence influence resident stem and progenitor cells. Some aspects of immune signaling are beneficial, promoting intrinsic plasticity and cell replacement, while others appear to inhibit the very type of regenerative response that might restore or replace neural networks lost in injury or disease. Here we review known and speculative roles that immune signaling plays in the postnatal and adult brain, focusing on how environments encountered in disease or injury may influence the activity and fate of endogenous or transplanted NSCs.

Introduction

Neural stem cells play many roles during prenatal development and throughout adult life. Although it is an over simplification to classify NSCs as being identical at all stages of life, many of the regulatory mechanisms that control stem cell behavior are conserved in development and in the adult. While the specific identity of NSCs in vivo is still debated, there are cells present within the central nervous system (CNS) at all stages of life that self renew and have the capacity to generate all three major cell types of the CNS: neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. The earliest NSCs arise as a single layer of columnar neuroepithelium that forms the neural tube and gives rise to neuron or glia-restricted progenitor cells. Through sequential proliferation and differentiation, neuroectodermal stem cells ultimately generate the entire CNS during prenatal and early post-natal development (Merkle and Alvarez-Buylla, 2006).

Stem and progenitor cells continue to produce neurons and glia well into childhood and maintain low-level cell replacement/addition throughout life (Ming and Song, 2005). Although glial progenitor cells are abundant and mediate continued production of glia throughout the brain, the natural production of new neurons is restricted to two locations in the adult: the subventricular zone (SVZ), which generates neuroblasts that migrate to the olfactory bulb where they participate in networks that mediate olfaction; and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus, which generates granular cell layer neurons involved in networks that modulate mood as well as short term learning and memory (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008; Ming and Song, 2005).

It is thought that stem cells residing in other areas of the brain have similar potential to generate neurons and injury can evoke an abortive production of new neurons outside of the two neurogenic areas, a fleeting phenomenon that provides a sliver of hope for future NSC-based therapies (Carmichael, 2008). However, the local signaling within these areas clearly restricts both the abundance and type of cell produced and the practical effect is that the mature CNS does not undergo substantial regeneration. The dogma of “no new neurons” is well deserved in virtually all regions of the adult brain. Accumulating evidence suggests that failure to produce neurons is not due to the absence of cells that could mediate neurogenesis since removal of NSCs from many areas of the brain allow them to generate neurons in vitro (Palmer et al., 1999) but rather due to local signaling that tightly constrains neurogenesis to a diminutive level in vivo (Dayer et al., 2005; Tamura et al., 2007). Ultimately, there is a broad continuum of homeostatic signals that act on self-renewing multipotent stem cells, committed progenitor cells and the terminally differentiated cells of the brain to control function, daily maintenance and minor repair (Ming and Song, 2005). Understanding these signals may provide methods for modifying or amplifying NPC response for repair.

Restoration of damaged neural networks in the adult remains one of the strongest forces driving research in NSC biology and the study of native process of neurogenesis within the hippocampus or olfactory system continues to provide new insights into how this might be achieved. The complex signaling environments that regulate the production of neurons and glia are adaptive and can respond to changes in local demand. For example, within the hippocampus, the production of new neurons is stimulated by local neuronal network activity, physical activity (such as running), environmental enrichment, and even simply the act of learning (Duan et al., 2008; Emsley et al., 2005). In the olfactory bulb, exposure to novel smells or other experiences that provide olfactory enrichment also promotes the production and retention of new neurons (Magavi et al., 2005; So et al., 2008). The implication is that areas which can produce neurons are more efficient at producing and retaining new neurons when natural demand on the local network is high.

Conversely, chronic stress and depression, as well as local or systemic inflammation are potent inhibitors of neurogenesis (Butovsky et al., 2006a; Cameron and Gould, 1994; Ekdahl et al., 2003; Monje et al., 2003; Tanapat et al., 1998). Disease and injury states also invoke immune and stress responses and understanding the both the natural positive and negative signaling networks that regulate NSCs in these unique neurogenic areas is relevant for designing future strategies to enhance regeneration.

While the global effects of manipulating an animal's health or experience on adult neurogenesis are incontrovertible, the specific molecules or cells that mediate each effect are still hotly debated. The intimate co-regulation of mood, stress response, the HPA axis, and immune cytokine signaling make it even more difficult to uncouple the specific effects of one physiology over another. For example, chronic stress is a well known inhibitor of NSC-mediated hippocampal neurogenesis. Early work implicated the HPA axis and elevated glucocorticoids as the primary inhibitory mechanism (Cameron and Gould, 1994; Tanapat et al., 1998) while more recent work shows that the stress effects are equally dependent on IL-1β signaling, one of the cardinal proinflammatory cytokines (Koo and Duman, 2008). In this case, the primary insult is not an immune challenge or tissue damage but rather a life experience or other environmental stressor that operates through an immune signaling intermediate. The complexity of feedback/feed-forward interactions (both systemic and local to the CNS) highlight the hazards that lie ahead in charting the role of immune signaling in adult neural stem and progenitor cell biology.

Immune Signaling in the CNS

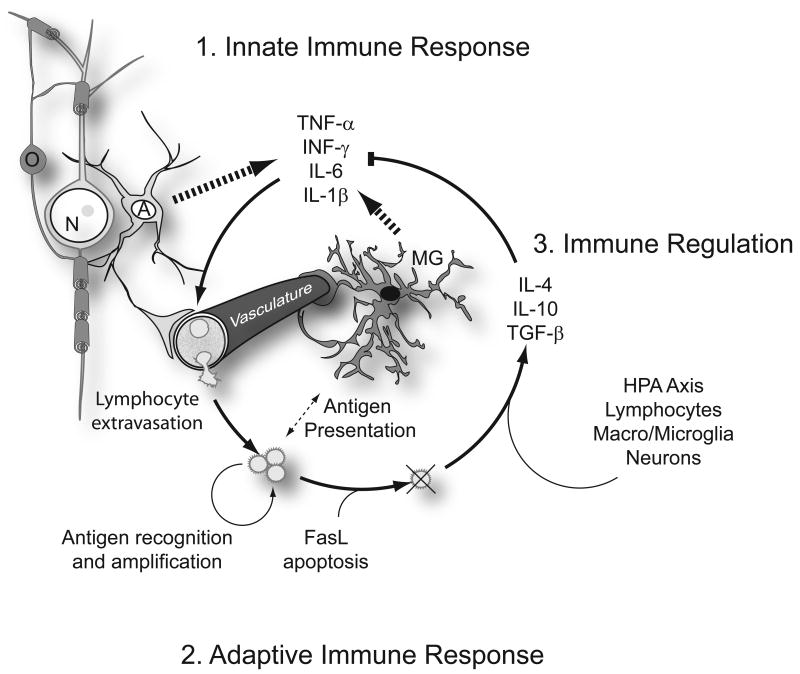

The immune system is best known for its protective role in the response to pathogens and tissue injury. An immune response follows a stereotypical sequence of events (Figure 1). Infection, injury or cell death initially triggers a local innate immune signaling cascade, mediated primarily by tissue resident cells that respond to pathogen-associated molecular patterns or proteins released by damaged cells. These molecular patterns bind and activate Toll-like receptors expressed by both immune cells and glia within the brain. Receptor activation initiates a pro-inflammatory cascade involving the transcriptional upregulation and subsequent release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in numerous cell types. In the brain, both microglia as well as macroglia and neurons express TLRs and associated cytoplasmic signaling elements (Bsibsi et al., 2002). Microglia are the largest source of proinflammatory cytokines following immune challenge. Cytokines then aid in the second phase of the immune response, the activation and recruitment of peripheral immune cells to sites of infection or injury. Dozens of signaling molecules are released in this first response but the primary mediators of the initial proinflammatory cascade include tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β. Cytokines act locally as well as within the circulation to activate vasculature and circulating lymphocytes. Circulating lymphocytes then bind to activated endothelium and extravasate into the site of immune response. Along with tissue-resident immune cells, they then mediate the elimination of pathogens through antigen recognition and T cell-mediated cytolysis and B cell-mediated antibody production.

Figure 1. Immune response in the CNS.

Immune signaling in the CNS follows a well characterized and stereotypical progression. 1. The innate immune response is stimulated as a consequence of infection, injury or cell death, which releases molecules recognized by Toll-like receptors. The initial immune recognition and signaling cascade is mediated primarily by astrocytes (A) and microglia (MG), tissue resident cells that recognize and respond to molecular patterns released by pathogens or damaged cells Astrocytes and microglia are also well known for their intimate contact with the vasculature astrocytic end feet form a tight vascular barrier that modulates immune cell and cytokine trafficking from the periphery. Toll-like receptor activation initiates production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Key among these are tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon- γ (INF-γ), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-1β. 2. The adaptive immune response is triggered by these cytokines and involves the activation and recruitment of peripheral leucocytes to sites of infection or injury. Cytokines act locally to activate cells of the vasculature as well as within the circulation to activate circulating lymphocytes, which then bind to activated endothelium and extravasate into the site of immune response. Relative to other tissues of the body, peripheral lymphocyte recruitment is attenuated by the astrocytic blood brain barrier (BBB) but injuries that damage the BBB or aggressive acute proinflammatory signaling can degrade BBB function and permit a full-scale adaptive response. Lymphocytes, along with tissue-resident immune cells, then mediate the elimination of pathogens through antigen presentation, recognition and amplification of effector T and B cells. 3. Immune regulation and resolution of the innate and adaptive responses follows clearance of the initiating molecular patterns and Fas-ligand (FasL)-mediated apoptosis of effector lymphocytes. The HPA axis, lymphocytes, macroglia, microglia, and neurons all further contribute to the production of anti-inflammatory hormones and cytokines such as glucocorticoids (via the HPA axis), TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-4.

The amplitude and duration of the immune response is largely self limiting as the molecular patterns that trigger and sustain the innate response are cleared and the effector T-cells and B-cells undergo programmed cell death. HPA axis activation during inflammation also elevates glucocorticoid synthesis which further attenuates proinflammatory signaling and ultimately the acute proinflammatory cytokine signaling cascade is superseded by an immunoregulatory profile of cytokines, many of which have anti-inflammatory properties, such as TGF-β, IL-4 and IL-10 (Elenkov and Chrousos, 2002). Direct brain-immune interactions also regulate the amplitude of the systemic immune response, mediated in large part by parasympathetic cholinergic signaling that acts to regulate the systemic elaboration of TNF-α (Wang et al., 2003). In the end, immune activation in the brain invokes both local and systemic responses through tightly coupled neuro-immune interactions at many levels.

Although the brain was once thought to be an immune privileged tissue, it is now recognized that classical immune responses do occur within the CNS, albeit with slightly different characteristics than in the periphery (Bailey et al., 2006). As for other tissues that utilize immune adaptations, such as the eye or the uterus during pregnancy, the brain utilizes a series of molecular mechanisms that attenuate the entry of leukocytes into the brain parenchyma and tightly regulate T-cell mediated adaptive immune recognition. This is accomplished in part by constitutive expression of Fas ligand (FasL) by astrocytes and neurons, which triggers the FasL-mediated apoptosis of activated T cells (Niederkorn, 2006). However, when the immune stimulus or injury is sufficiently large, resident glial cells (both astrocytes and microglia) are capable of producing a full complement of cytokines and chemokines and subsequently mediating the recruitment and activation of cells of the peripheral immune system (Bailey et al., 2006).

Glial activation, and particularly microglial activation, is a hallmark of inflammation in the CNS. Activated astroglia and microglia a produce a host of immune mediators and many studies over the last few years have shown that this immune signaling is able to perturb adult NSC activity and fate. NSCs themselves express receptors and ligands related to the innate and adaptive immune responses, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a variety of cytokine and chemokine receptors, major histocompatibility complex I (MHC I), numerous cell adhesion molecules utilized for extravasation by lymphocytes (Covacu et al., 2009; Imitola et al., 2004; Johansson et al., 2008; Pluchino et al., 2003; Rolls et al., 2007; Tran et al., 2007). The range of molecules expressed supports the surprisingly broad influence of signaling molecules previously thought relevant only to cells of the immune system.

Tissue injury, degenerative disease or infection in the CNS is invariably accompanied by immune activation (Bailey et al., 2006) but the impact of activated microglia or astroglia and the effectors they release proves to be complex, as immune signaling has both pro-inflammatory and pro-regenerative components that undergo temporal and contextual changes. The literature is rife with conflicting reports about the specific influence of a given molecular ligand or receptor, perhaps due in part to the dynamic nature of this response and the varied roles that a given cell or cytokine can play within the changing inflammatory environment. For example, conditioned media from normal microglia has been shown to increase neurogenesis in cultures of NSCs while others show that conditioned media inhibits neurogenesis (Aarum et al., 2003; Nakanishi et al., 2007). Other reports discriminate between resting, activated and immunomodulatory (or anti-inflammatory) microglial states, each having minimal, negative, or positive effects respectively (Butovsky et al., 2006a; Monje et al., 2003). In many cases, conflicting data can later be reconciled by taking into account the broader role that each cell or cytokine might play in the ongoing of symphony of immune signaling. In a sense, immune signaling is never absent but instead maintained in a constant balance between quite but active surveillance, stimulus response, and modulation of the response to restore stateful vigilance (Figure 1).

The Impact of Inflammatory Signaling on Adult Neurogenesis

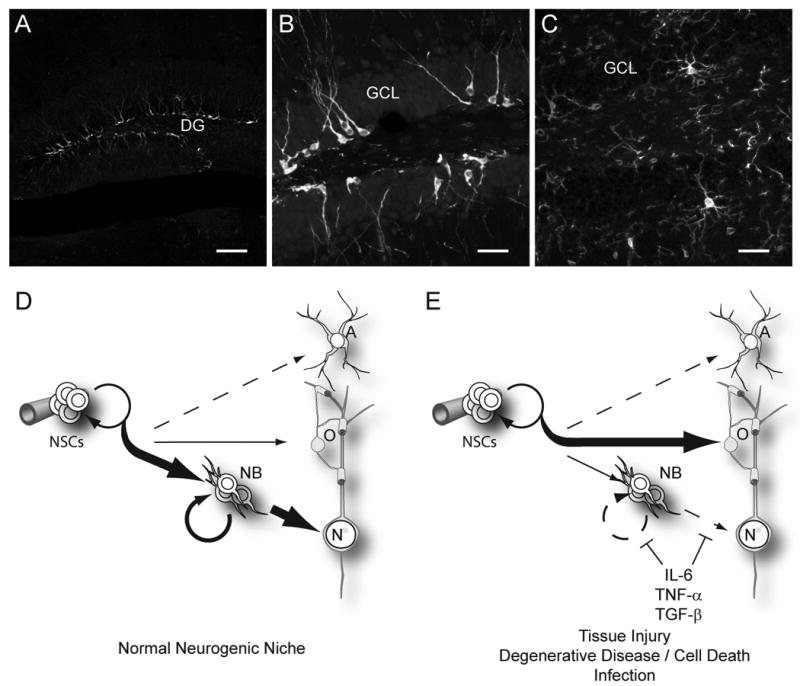

One area where agreement seems to have been reached is that acute activation of local or systemic innate pro-inflammatory cascades has a profound negative effect on postnatal and adult neurogenesis (Figure 2). Proinflammatory signaling can be experimentally modeled in many ways but one of the most common methods is through the injection of pathogen molecular pattern that mimic viral or bacterial infections. Commonly, researchers use viral mimics such as polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly IC) or bacterial cell wall components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), each potent activators of the innate immune system via Toll-like receptors. LPS injection is more widely used to model neuroinflammation and produces an acute innate response through activation of TLR4. LPS activation leads to a variety of responses in immune cells, including the production of cytokines and chemokines as well as activating antigen presenting cell functions to promote recruitment of the adaptive immune system (Uematsu and Akira, 2006). LPS infused chronically into the brain causes widespread microglial and astroglial activation and strongly suppresses neurogenesis in the adult rodent hippocampus (Ekdahl et al., 2003). Remarkably, even a single injection of LPS into the periphery of rodents is sufficient to cause a chain of immune signaling in the periphery that ultimately causes microglial activation in the brain and suppress neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Monje et al., 2003). Hippocampal neurogenesis can be partially restored by broad spectrum nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) under these conditions (Bastos et al., 2008; Monje et al., 2003) suggesting that simple immunomodulatory approaches can be beneficial. In addition, one of the target pathways, prostaglandin synthesis, appears to be key in this process since the absence of prostaglandin receptors E1 and E2 protects neurogenesis from the inflammatory signaling cascade evoked by LPS (Keene et al., 2009). Although system wide modulation of immune signaling does influence the amplitude of effect on neurogenesis, there is still considerable uncertainty about the specific NSC intrinsic vs. extrinsic signaling that mediates these effects.

Figure 2. Impact of proinflammatory signaling on neurogenesis in the adult.

A, B. Neurogenesis naturally occurs within the dentate gyrus (DG) of the adult mouse hippocampal formation. Neural stem cells (NSCs) divide to produce progeny that differentiate into an abundant population of doublecortin expressing newborn neurons (white). These immature neurons decorate a thin neurogenic lamina underlying the granular cell layer (GCL). C. As for other regions in the brain, Iba-1-stained microglia (white) in the dentate gyrus send highly ramified processes throughout the tissues, leaving no cell untouched. This intimate association with all cells of the brain allows microglia to constantly and efficiently monitor for infection or cell death and respond by initiating an innate immune response. D. Under normal conditions, the neurogenic niche of the hippocampus strongly favors the production of new neurons (N). This involves first generating a transient amplifying neuroblast (NB) pool, which subsequently differentiate and mature to become integrated within the pre-existing neural networks. Within this region, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes are also produced, though to a much lesser extent. Neurogenesis is supported in this region as well as within the SVZ of the olfactory system by local cues, some of which are provided by cells of the vasculature. In other areas of the brain, oligodendrocytes are the primary product of cycling progenitor cells. E. Upon activation of the innate proinflammatory response, NSC behavior is strongly altered to favor oligodendrocyte production. Of the proinflammatory cytokines released in this initial cascade, IL-6, and TNF-α are well known for their inhibitory effects on neurogenesis. Although TGF-β also plays a role in immune modulation and resolution, it has pleiotropic effects in immune signaling and is also known to impair neurogenesis when chronically over-produced (Buckwalter et al., 2006). In combination, these cytokines impair neuroblasts proliferation as well as reduce survival, maturation, and integration of newly generated postmitotic neurons. (Scale bars = 100 μm in A, 25 μm in B, C)

NSCs reportedly express TLR4 in the adult SVZ some have reported that TLR activation might influence NSC proliferative activity (Covacu et al., 2009; Rolls et al., 2007). It is possible, although not yet shown, that hippocampal NSCs also express TLR4 in vivo, which could give them the ability to directly respond to LPS. However, animals appear to have normal levels of BrdU labeling and production of immature neurons in the hippocampus immediately after LPS challenge, indicating that LPS does not directly inhibit the proliferation or initial neuronal fate of NSCs (Bastos et al., 2008; Ekdahl et al., 2003). Yet if the animals are sacrificed at later times after BrdU administration, the total number of surviving BrdU labeled newborn neurons is decreased (Bastos et al., 2008; Ekdahl et al., 2003; Monje et al., 2003), suggesting that the inflammatory cascade is inhibiting neuron maturation and survival rather than influencing the NSC proliferative activity directly. Though again results seem to differ between groups with some reporting TLR-mediated effects on undifferentiated stem cells while others finding no evidence of a direct effect in vitro. (Bastos et al., 2008; Monje et al., 2003). One confounding variable is that LPS preparations are not always equivalent and can show varied specificity for TLR4 vs. other TLR family members and the genetic modeling to selectively ablate TLR4 only within neural stem cells vs. differentiating neuroblasts has not yet been done.

The consequences of proinflammatory signaling on NSCs go beyond simple changes in the abundance of new neurons. Recent evidence also suggests that those few neurons that are produced during an inflammatory episode are functionally altered (Jakubs et al., 2008). The neurons generated during the period of inflammation are morphologically normal, with normal cell body location, polarity, and branching, yet they display an accentuated inhibitory or excitatory responses in immature vs. mature neurons respectively (Jakubs et al., 2008). This implies that both that quantity of new neurons as well as the synaptic quality of newborn neurons are affected by immune signaling.

The effects of LPS-induced inflammation on the brain are not limited to micro and macroglia but microglia do become strongly activated are likely to be the most significant source of cytokines that inhibit neurogenesis (Ekdahl et al., 2003; Monje et al., 2003). Microglia ubiquitous and highly ramified throughout the CNS and this complex arborization ensures that all cells of the brain are capable of intimate communication with the primary immune monitoring cell of the CNS (Figure 2C). Activation of microglia with LPS causes the production of factors in vitro that inhibit the generation of neurons from NSCs including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF- α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Monje et al., 2003). However, modification of microglial status by other cytokines, such as IL-4 or low dose interferon-γ (IFN-γ), changes their phenotype to strongly promote neurogenesis(Butovsky et al., 2006b). The positive effects are at least partly dependent on microglia production of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a potent pro-neurogenic growth factor. Though controversial, this raises the possibility that some types of controlled inflammation may be exploited in CNS regeneration or in combating neurological diseases that have pronounced chronic pro-inflammatory components (Rolls et al., 2009; Schwartz, 2000).

Inflammation and impact on NSCs and Neurogenesis in Neurological Disease

Neural stem cells have the ability to mediate limited repair in the CNS, however, this process is largely limited to the production of oligodendrocytes or astrocytes and rarely achieves a full restoration of function after disease or traumatic injury. Currently only one group has reported the regeneration of complex long-tract projection neurons following a highly selective and non-traumatic elimination of cortical projection neurons (Magavi et al., 2000). Here, caged compounds were used to retrogradely label neurons and photo-activated apoptosis caused precise dropout of cortical projection neurons while provoking very little collateral damage or inflammation. Although an interesting proof-of-principle experiment, injury conditions this “clean” rarely exist in real life. By the time a degenerative disease becomes clinically detected, inflammation is rampant and endogenous neuronal repair, if present, is influenced by the ongoing inflammatory processes. In a disease setting, it is likely that pro-inflammatory signaling plays a central role in inhibiting neuronal replacement in the CNS. Immunomodulation may be an important adjunct therapy in many contexts and several disease or injury models are beginning to shed light on how immune signaling influences the endogenous or transplanted NSC.

Insights from Neurodevelopment

Although immune signaling is highly relevant in adult disease or injury, the potential effects of inflammation on networks produced during fetal development are equally relevant and provide plausible mechanism by which immune modulation during pregnancy might produce far-reaching functional changes in the adult (see accompanying reviews by Boulanger as well as Deverman and Patterson in this issue). Recent observations show that molecules classically involved in the immune response are also naturally involved in CNS development (Huh et al., 2000; Ma et al., 1998; Stevens et al., 2007; Zou et al., 1998) and it seems likely that lessons learned in developmental models may have relevance in the adult.

Many groups have reported an epidemiologic linkage between maternal infection during pregnancy with neurodevelopmental disease in the offspring, including developmental delay, cerebral palsy, schizophrenia and autism (Ellman and Susser, this issue). The link between schizophrenia and autism and maternal infection appears to occur early in gestation (late first or second trimester) (Beversdorf et al., 2005; Brown et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2007), a time at which NSCs in the brain are rapidly cycling and generating neurons. Multiple reports confirm that an inflammatory challenge to a pregnant rodent can lead to behavioral abnormalities in the offspring (Meyer et al., 2006; Shi et al., 2003; Zuckerman et al., 2003). In a mouse model of maternal immune activation by poly I:C or maternal viral infection at embryonic days 9.5-12.5, there are lower numbers of Purkinje cells in the post natal brain and some appear to be ectopically placed (Shi et al., 2009). This is consistent with altered NSC proliferation or neuronal progenitor migration through cytokine signaling in the fetal brain, which can occur following maternal inflammation (Cai et al., 2000). Indeed, maternal blockade of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 is able to restore normal behavior in mice exposed to prenatal inflammation (Smith et al., 2007). It appears that similar mechanisms are conserved between NSCs in development and in the adult since over expression of IL-6 by astrocytes in the adult also impairs neurogenesis within the hippocampus (Vallieres et al., 2002) and much can be gleaned from the ongoing neurodevelopmental studies for potential application in adult NSC biology.

Neuroinflammation and impaired postnatal neurogenesis following treatment for pediatric brain cancers

Cranial radiation therapy is crucial to the successful treatment of many primary brain tumors, cancers metastatic to the brain, CNS involvement of leukemia/lymphoma, and head and neck cancers. Unfortunately, irradiation of the brain causes a debilitating cognitive decline in the years following treatment, especially in young children (Monje and Palmer, 2003). It has been hypothesized that this cognitive decline is in part due to the ablation of NPCs and the dependent processes of postnatal gliogenesis and neurogenesis. Rodent models showed that the effects of irradiation were surprisingly selective for neurogenesis (Monje et al., 2002). Isolation of NPCs from the irradiated brain showed that NPCs were present and capable of generating neurons but for some reason were not being utilized within the adult hippocampus. It was subsequently determined that irradiation injury induced a chronic inflammatory state that did not resolve and that treatment of irradiated rodents with NSAIDs was able to partially restore hippocampal neurogenesis (Monje et al., 2002; Monje et al., 2003). These results, along with similar data on inflammatory inhibition of neurogenesis in an epilepsy model (Ekdahl et al., 2003) were the first to uncover the ties between neurogenesis and inflammatory signaling. Subsequent studies have confirmed that the normally abortive regenerative response evoked by injury such as stroke can also be potentiated by simple NSAID-mediated attenuation of the proinflammatory response (Hoehn et al., 2005b).

A balance of inductive and inhibitory stimuli in epilepsy

In animals, the induction of status epilepticus causes a dramatic increase in neurogenesis in the hippocampus for two weeks following the initiation of seizures (Parent et al., 1997), in part due to the large increase in neuronal activity which promotes the generation of new neurons. Network activity within the hippocampus amplifies neurogenesis through several mechanisms. NSCs can sense local elevations in excitatory neural transmitters that are released when networks are active (Deisseroth et al., 2004) and the resulting signaling through NMDA receptors and L-type calcium channels promotes transcriptional activation of proneural genes within the NSC. Elevated network activity can also cause transcriptional alterations in mature neurons leading to persistent changes in the transcription of neuron-produced growth factors such as VEGF or BDNF, each also known to promote neurogenesis through their direct actions on NSC and neural progenitor cells (Ma et al., 2009; Schmidt and Duman, 2007; Segi-Nishida et al., 2008).

In contrast, at longer time points after the seizure, neurogenesis is severely depressed (Bonde et al., 2006; Borges et al., 2003; Hattiangady et al., 2004) and is accompanied by evidence of gliosis and neurodegeneration (Blumcke et al., 2001). Persistent microglial activation accompanies the seizure activity and treatment of mice that have experienced seizures with the anti-inflammatory drug minocycline further increases the abundance of new neurons surviving following seizure (Ekdahl et al., 2003). Minocycline is used primarily as an antibiotic with good blood-brain barrier permeability but it also used extensively for its effective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory properties (Kim and Suh, 2009). Emerging evidence suggests it may also have direct anti-apoptotic actions, though its exact molecular target is still elusive (Kim and Suh, 2009). In this experimental seizure model, minocycline treatment decreased the number of activated microglia in the brain along with increasing the number of newborn neurons, and this effect was seen even in the context of little overt tissue damage (Ekdahl et al., 2003). In contrast, a commonly used cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitor actually has the opposite effect and inhibits neurogenesis induced by seizures, which may be due to direct effects on COX-2 activity in NSCs (Jung et al., 2006). In epilepsy, while later stages would appear to benefit from increased neurogenesis, the robust native increase in neurogenesis immediately after seizure is likely pathogenic (Parent et al., 1997). Here, the timing of an intervention may be critical. Use of anti-inflammatory strategies to increase neurogenesis at the onset of seizure activity may be counterproductive while immunomodulatory drugs to target the later period of degeneration and impaired neurogenesis may be beneficial. It is likely that inflammation is one of several factors that mediate the decline in neurogenesis in chronic epilepsy, as alterations in pro-neurogenic growth factors or the depletion of NSCs could also play a role (Hattiangady and Shetty, 2008).

Neurogenesis, stress and clinical depression

The hippocampus and its interactions with the limbic system are thought to be critical to the pathogenesis of depression (Sahay and Hen, 2007). Patients with depression generally show decreases in hippocampal volume and deficits in hippocampus-dependent learning and memory similar to those noted in animals following chronic stress. In animals, stress is accompanied by decreased hippocampal neurogenesis and there has been speculation that the absence of neurogenesis may itself lead to depression. However current evidence suggests that loss of neurogenesis is not causative (Sahay and Hen, 2007) but may in play an unsuspected role in mediating the relative efficacy of anti-depressants that inhibit serotonin reuptake (Malberg et al., 2000; Santarelli et al., 2003). In the absence of neurogenesis this class of antidepressants has little effect in animals.

Depression is often the consequence of severe chronic stress and, as mentioned above, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 β also appear to be involved in the reduction of neurogenesis in animal models of depression (Goshen et al., 2008; Koo and Duman, 2008). Given the dynamic interactions between HPA axis, glucocorticoid modulation of immune signaling, the glucocorticoid and cytokine effects on neurogenesis and consequent efficacy of SSRIs in treating depression, it seems likely that novel therapies for depression may ultimately include targeted manipulation of immune signaling or other approaches that promote neurogenesis.

Multiple sclerosis, oligodendrogenesis, and evidence for reciprocal signaling between NSC and immune cells

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system characterized by an early loss of white matter followed later by degeneration of the demyelinated neurons. A large amount of work has focused on how to replace oligodendrocytes (the myelinating cells of the CNS), which are lost during disease. There are two types of progenitor cells which have the capacity to generate oligodendrocytes: the neural stem cell and the more lineage restricted oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC). Naturally occurring OPCs are capable of remyelinating axons under some circumstances, especially in toxin induced models of demyelination in rodents (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008). However, these are acute models which lack the chronic inflammation in the CNS of MS patients. In patients, some remyelination may occur natively, but the process ultimately fails to restore normal nerve conduction (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008).

The focus on oligodendrocyte generation by NSCs or OPCs in MS offers different challenges from diseases which requiring neuron generation. Not only do NSCs in the SVZ naturally generate OPCs and oligodendrocytes but OPCs migrate and are present throughout the neuraxis (Franklin and Ffrench-Constant, 2008). Furthermore, inflammation, thought to be detrimental to neurogenesis, may actually promote the generation and functional maturation of oligodendrocytes. In three distinct models of demyelination, artificially increasing the level of inflammation in the area promotes remyelination from endogenous or exogenous OPCs, possibly due to the induction of growth factors which support oligodendrocyte development (Foote and Blakemore, 2005; Glezer et al., 2006; Setzu et al., 2006). However, these authors examined genetic and toxin-induced models of demyelination with acute inflammatory stimuli. In MS patients, where inflammation is chronic and specifically targets the oligodendrocyte, the potential detrimental effects of inflammation may prevail (also see accompanying Review by Bhat and Steinman, this issue, for more information on neural-immune crosstalk in MS).

OPCs are present in MS plaques, but they ultimately fail to remyelinate denuded axons (Kuhlmann et al., 2008; Wolswijk, 1998). Recent in vivo evidence suggests this failure is due to a block in the differentiation of these cells rather than their survival or recruitment (Kuhlmann et al., 2008). It therefore appears that the environment is a key factor in remyelination failure in MS, and the presence of chronic inflammation is a likely factor. Several cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β, have been reported to have block OPC differentiation, as well as proliferation and survival, in vitro (Agresti et al., 1996; Andrews et al., 1998; Vela et al., 2002).

Overall, this work suggests a simple NSC or OPC transplant strategy for the treatment of this disease is unlikely to be successful due to the hostile environment to remyelination. However, several groups have shown that transplant of NSCs, derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) or adult mouse SVZ, into mouse models of multiple sclerosis are effective in ameliorating disease symptoms (Aharonowiz et al., 2008; Pluchino et al., 2003; Pluchino et al., 2005). Surprisingly, in two of these three studies the authors were unable to detect a significant amount of transplanted cells differentiating into myelinating oligodendrocytes, and failed to detect any increased remyelination despite the functional improvement (Aharonowiz et al., 2008; Pluchino et al., 2005). Rather, two independent groups have reported that the effects of NSC transplant in this model are due to unexpected immunosuppressive properties of the NSCs (Einstein et al., 2007; Pluchino et al., 2005). Both these studies and subsequent in vitro studies have implicated T cells as the target of this immunosuppression, by inhibiting T cell proliferation and differentiation or inducing T cell apoptosis (Einstein et al., 2007; Pluchino et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2009). Perhaps the most convincing of these studies is the observation that primed T cells from a mouse treated with NSCs are deficient in their ability to adoptively transfer disease, demonstrating a lasting inhibition of the encephalitogenicity of the T cells rather than an effect specific to their environment (Einstein et al., 2007). These studies serve to remind us that immune-NSC signaling is not a one-way street and that NSCs also exert some control over local immune responses.

Stroke and the abortive induction of native neurogenesis

Stroke increases the number of newborn neurons in peri-infarct areas of the cortex and striatum, presumably through the induction of injury-related signals that recruit the migration of neuron progenitor cells from the ventricular zone into the damaged parenchyma (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2006; Parent et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2001). These newborn cells persist for at least 5 weeks after stroke and ultimately express markers of mature neurons (Parent et al., 2002). Furthermore, those cells which persist in the striatum express specific markers of medium spiny neurons, the major neuronal cell type in the striatum (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Parent et al., 2002), as well as demonstrating appropriate neurotransmitters, synaptic structures, and the ability to send and receive electric signals (Hou et al., 2008). The source of these cells is the SVZ, where stroke appears to increase the pool of NSCs by inducing a switch from asymmetric to symmetric amplifying divisions (Zhang et al., 2004). In spite of this native response, the number of newborn cells surviving under normal conditions in the striatum or cortex is very low (on the order of a few dozen to a few hundred per mm3) (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2006; Parent et al., 2002). In contrast, the increase in newborn neurons within the SVZ proper is more robust with a 50% increase over the 2 weeks after stroke, corresponding to an extra 1000 cells/mm3 (Zhang et al., 2001). These numbers suggest that a majority of the new cells generated in the SVZ in response to stroke are not recruited into the parenchyma and are ultimately eliminated.

Although not without controversy, studies using different NSAIDs now indicate that anti-inflammatory treatments around the time of stroke is able to enhance the accumulation of newborn neurons (Hoehn et al., 2005a; Kauppinen et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2007). Currently, only one of these groups has examined functional outcome, and found that minocycline was protective (Liu et al., 2007). However, it is unclear whether the behavioral protection was due to increased neurogenesis, decreased inflammation, or other factors. One further study has examined NSC transplants and has shown, similar to studies in MS models (Einstein et al., 2007; Pluchino et al., 2005), that NSC transplants are protective in stroke though few new neurons were produced and there is speculation, largely on the basis of earlier reports that NSCs can be immunomodulatory (see MS section above), that the protection is due to anti-inflammatory effects of the transplanted NSCs (Lee et al., 2008).

Neurodegenerative disease and chronic microglial activation

Many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, are accompanied by increasingly widespread neuroinflammation characterized by chronic activation of microglia and production of proinflammatory cytokines (see accompanying article from Lucin and Wyss-Coray, this issue). Studies in multiple animal models (and putatively in Parkinson's patients) report a decrease in neurogenesis during disease, especially in the SVZ and olfactory bulb (Baker et al., 2004; Hoglinger et al., 2004; Winner et al., 2004). Whether inflammation contributes to this phenotype is unclear, because the loss of dopamine may itself lead to decreased neurogenesis (Borta and Hoglinger, 2007). In Alzheimer's disease, there is no current consensus on whether neurogenesis is impacted. In a majority but not all animal models, neurogenesis is inhibited, most likely after the beginning of amyloid plaque deposition, the primary pathological hallmark of AD, but human studies have largely failed to confirm these results (Kuhn et al., 2007). These conflicts await resolution, but maybe related to age, length of disease, and different characteristics of the different disease models, each of which mimics loss of neurons but does not recapitulate the native neurodegenerative process.

Curiously, in both Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's diseases, there are behavioral manifestations in humans suggestive of defects in hippocampal networks that are influenced by neurogenesis (decreased spatial memory and high rates of depression) as well as deficits in olfactory networks that are also influenced by adult neurogenesis. (Gabryelewicz et al., 2007; Hawkes, 2006; Matsuda, 2007; Poewe, 2008). In fact, loss of olfactory acuity has been cited as one of the earliest clinical manifestations of degeneration in both Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease (Hawkes, 2006). Similarly, symptoms of depression and changes in hippocampal volume and activity are often seen as antecedents of clinical diagnosis for both these diseases (Bruck et al., 2004; Gabryelewicz et al., 2007; Matsuda, 2007; Poewe, 2008). Though highly speculative, it is possible that inflammation impairs neurogenesis in these areas and that NPC dysregulation contributes to the early disease biomarkers as well as to overall degenerative process, particularly within the respective neurogenic areas of the brain.

Transplantation of NSCs and Inflammation

The use of NSCs for transplantation has been suggested as a therapy for many neurodegenerative diseases (Ormerod et al., 2008). In general, the goal of such a transplant would be to replace cells lost during the disease process, usually neurons or oligodendrocytes. One benefit of this approach in the CNS is that allogeneic cellular grafts into the CNS can exhibit long term survival even after immunosuppressive withdrawal (Chen and Palmer, 2008). In addition to cell replacement, stem cell therapy may be used to improve outcome by other means. NSCs can be genetically modified to produce supportive growth factors and cytokines to protect the remaining cells from loss rather than seeking to replace them (as reviewed in (Ormerod et al., 2008). Furthermore, the unexpected anti-inflammatory properties of NSC transplants may serve to improve disease state by modifying the injury or inflammatory process without having to differentiate at all (Einstein et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2008; Pluchino et al., 2005).

The environment of the diseased brain almost invariably has an inflammatory component which could affect the outcome of the transplant in several ways. It is possible that inflammation may benefit the efficacy of a transplant by directing NSCs to the site of injury. NSCs express a variety of chemokine receptors in vivo (Tran et al., 2007), and chemokines are widely expressed during CNS inflammation (Bailey et al., 2006), suggesting that NSCs could be specifically recruited to areas of injury of inflammation. Indeed, NSCs are able to migrate in response to chemokines generated after injury in vivo, with particularly important roles for the chemokines CCL2 and CXCL12 (Imitola et al., 2004; Yan et al., 2007). Recently, it has been shown in multiple disease models that even NSCs injected intravenously are able to infiltrate sites of CNS injury (Chu et al., 2004; Fujiwara et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2005; Pluchino et al., 2003). Although vascular delivery not the most efficient method of delivering cells (Tang et al., 2003), the obvious advantage of intravenous administration (should it prove compellingly effective for unknown reasons) is its clinical ease and lack of invasiveness.

Inflammation in the CNS likely to limit the efficacy of current transplant strategies. The preponderance of evidence indicates that transplanted NSCs will be ineffective at generating neurons in particular, given the inhibitory effect of proinflammatory signaling on neurogenesis in adult animals (Ekdahl et al., 2003; Monje et al., 2002). Furthermore, it should also be recognized that not only will transplanted cells encounter an inflamed environment, but they may contribute to it. The use of allogeneic embryonic stem cells or fetal brain-derived neural stem cells is widely contemplated and entering clinical trials yet these cells would not be immunologically matched to the host. There is even a long history of both experimental and clinical use of xenografts (cells from another species) with mixed outcome. There should be careful consideration of the source of cells for transplantation into the CNS, and in particular the immune response that an allograft or xenograft may elicit from the host after transplant.

MHC I is a critical mediator of graft rejection and plays a key role in the ability of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells to recognize “non-self” tissue, including the presence of foreign MHC as well as the absence of “self” MHC. The constitutive expression of MHC I on NSCs has been reported (Corriveau et al., 1998; Johansson et al., 2008). Although others have found expression weak or undetectable under baseline conditions (Hori et al., 2003; Mammolenti et al., 2004; Preynat-Seauve et al., 2009c), there is wide consensus that exposure to inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α stimulates MHC expression in NSC (Hori et al., 2003; Johansson et al., 2008; Mammolenti et al., 2004; Preynat-Seauve et al., 2009b). This renders the NSC recognizable by T cells or natural killer cells in vitro, leading to classical immune mediated cytolysis. (Mammolenti et al., 2004; Preynat-Seauve et al., 2009a). Although some have argued that stem cell grafts would be “invisible” due to the lack of MHC expression, the inflammatory contexts in which these cells would be used virtually guarantees that transplanted NSCs would express high levels of MHC and would be readily recognized by infiltrating T cells.

Despite differences in adaptive immune signaling between the periphery and the CNS, the CNS is still fully capable of rejecting xenografts and allografts (reviewed in (Chen and Palmer, 2008). For example, in one study, xenograft transplants of embryonic brain tissue into the brains of mice were rejected, but allografts survived at least 42 days (Mirza et al., 2004). Allograft survival is due in part to the low immune surveillance and active inhibition of T cell responses in the CNS (Bailey et al., 2006), but it may also be due to the properties of the transplanted cells themselves. One study has reported that NSCs transplanted into the kidney capsule survive at least 28 days, whereas control CNS tissue is rejected in the same time frame (Hori et al., 2003). Determining the properties of cells which allow for relatively long survival times in some allografts, and how these conditions might be leveraged to improve outcome, is crucial to moving forward with CNS transplantation using mass-produced allogeneic cellular reagents.

Ultimately, however, allografts do elicit an immune response in the CNS and this can lead to graft rejection. In a rat models of spinal cord injury, NSC allografts were ultimately rejected after an extended period of growth and maturation (Theele et al., 1996). Even when grafts survive, numerous CD45+ cells are observed around the allograft in both mice (Ideguchi et al., 2008b) and in humans who received grafts of fetal nigral tissue to treat Parkinson's disease (Kordower et al., 1997). Numerous immune lineage cells were observed around the graft, including macrophages, T and B cells, although the grafts survived over a period of 18 months in humans, even after withdrawal of immunosuppression, the consequences of this chronic inflammatory state are unlikely to be beneficial. Indeed, when compared to syngeneic grafts, allografts not only show decreased survival (Muraoka et al., 2006b; Theele et al., 1996), but also decreased migration away from the transplant site and decreased differentiation of neurons (Muraoka et al., 2006a), an effect that can be partially prevented using the immune suppressive effects of cyclosporine A (Ideguchi et al., 2008a; Theele et al., 1996). These results suggest that immune suppression an accompanying risks of chronically compromised immune function may be a necessary reality for allografts to survive and efficiently generate neurons. However, we await studies to determine whether milder immunosuppressants or the tapering off of immunosuppression is compatible with long-term efficacy.

The use of patient-derived fibroblasts to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) (Takahashi et al., 2007) may ultimately supersede allograft transplantation. There is a great deal of excitement over the use of iPSCs for transplant therapy in a variety of diseases. iPSC lines have been created from patients with neurological disease such as Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) (Dimos et al., 2008; Ebert et al., 2009b; Soldner et al., 2009). One obvious advantage of using these cells for transplant would be that they are a perfect immunological match to the host. However, they could have disadvantages as well; neurons derived from iPSCs from SMA patients have defects in cell survival in vitro (Ebert et al., 2009a), likely as a result of this genetic mutation which causes this disease. In diseases arising from a single or well defined genetic alteration, the mutated genes could be altered in the iPSCs prior to transplant. This has been shown to be effective strategy in mice with sickle cell anemia treated with iPSCs which were genetically altered to express normal hemoglobin (Hanna et al., 2007). However, it is worth noting the normal protein produced in a deficient host could be seen by the immune system as “non-self” and targeted for an immune response. Whether this type of immune attack of an altered autologous cell will occur in this NSC-transplant scenario is entirely unknown, but will be important to determine prior to clinical use. It is also very important to keep in mind that most cases of neurodegenerative diseases are idiopathic with no known genetic anomaly. It is unclear whether patient-derived cells in these diseases will carry an intrinsic defect, and whether this would need to be corrected to allow for normal function and survival. In this case, allografts of normal cells, even if not perfectly immunologically matched, may be preferable. A great deal of research still needs to be done to determine the best type of cells to transplant for any given disease, and possibly for any given patient. The most fundamental of these experiments are those that critically test whether stem-cell based treatments are in fact beneficial.

To date, there has been limited exploration of iPSCs in treatments for neurologic disease. In a toxin-induced model of Parkinson's disease in rats (Wernig et al., 2008a), the cells survived and integrated in the host brain, but the authors noted the appearance of teratomas arising from undifferentiated cells (Wernig et al., 2008b). Addressing the propensity of iPSCs to form cancers following transplantation (or indeed any undifferentiated cell regardless of source) will be key to moving stem cell-based therapies into the clinic.

Proinflammatory cytokines and their impact on NSCs and neurogenesis

One of the common effects of immune activation is the production of cytokines, and in the CNS cytokines are primarily produced by activated microglia but also generated by astrocytes, and infiltrating immune cells (Bailey et al., 2006). Cytokines are the secreted molecules that mediate communication between immune cells and between immune system and host. Cytokines encompass a broad class of signaling molecules that have the potential to influence an immense variety of signals which regulate NSC function, including growth factor production, electrical activity, synaptic function, and axonal path finding. Cytokine-mediated effects on neural development are discussed in detail elsewhere in this issue and we refer interested readers to the review by Deverman and Patterson for further information. For the purposes of this review, we will limit our discussion to an overview of the cardinal proinflammatory cytokines that are known to have a prominent inhibitory effect on adult neurogenesis in vivo and which have been strongly implicated in the injury and disease models discussed above. These include TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β.

TNF-α

TNF-α is well known for its pro-inflammatory functions in the immune system, where it is produced by a variety of cells including T cells and macrophages. In the brain, TNF-α has the paradoxical ability to both protect and destroy neurons (McCoy and Tansey, 2008). TNF-α signals through 2 distinct receptors: TNF-α receptor 1 (TNFR1), the major mediator of pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic functions of TNF-α, and TNFR2, which activates more pro-growth and survival pathways.

Reported effects of TNF-α on NSC proliferation and differentiation are highly conflicting, with various groups reporting increases or decreases in proliferation and the differentiation of neurons (Ben-Hur et al., 2003; Bernardino et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2005; Widera et al., 2006). The source of this variation is not entirely clear but could be related to the species of cell, age or location of isolation, amount of time in vitro, concentration or time of treatment during differentiation, or the cells predominant expression of TNFR1 vs. TNFR2. The only consistency seems to be that several groups have now reported that TNF-α can induce apoptosis in NSCs or newborn neurons via TNFR1 (Cacci et al., 2005; Sheng et al., 2005; Widera et al., 2006). TNFR1 signaling, but not TNFR2, has been demonstrated to inhibit neurogenesis in the normal hippocampus (Iosif et al., 2006). In contrast, direct injection of TNF-α into the ventricles increased proliferation of SVZ cells (Wu et al., 2000), though it is not immediately clear which cell lineage was proliferating (immune vs. neural progenitor) and whether this effect was TNFR1 or TNFR2 mediated was not addressed.

There is significant evidence that TNF-α signaling plays a role in a variety of disease processes, and whether that effect is positive or negative appears to depend on whether activation of TNFR1 or TNFR2 predominates. For example, TNFR1 deficient mice have increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus following seizure, but TNFR2 deficient mice have decreased seizure induced neurogenesis (Iosif et al., 2006). Similarly, TNFR1 deficient mice have increased proliferation and newborn neurons in the SVZ following stroke (Iosif et al., 2008). However, the infusion of anti-TNFα antibody after stroke to block all TNF-α signaling is detrimental to the survival of stroke-induced newborn neurons (Heldmann et al., 2005), likely due to the loss of TNFR2 signaling. TNF-α has a similar role in the generation of new oligodendrocytes, as TNFR2 signaling is specifically required for remyelination by OPCs in a toxin-induced model of demyelination (Arnett et al., 2001).

IL-6

IL-6 is a member of a family of cytokines which signal through the gp130 receptor which includes ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF). CNTF and LIF have roles in promoting neural stem cell self renewal and astrocyte differentiation from NSCs (Shimazaki et al., 2001; Taga and Fukuda, 2005). Since they all use the same signal transducing molecule (gp130) to signal into the cell, it is likely that IL-6 also promotes the generation of astrocytes. In vivo, gp130 deficient animals die perinatally and demonstrate a lack of astrocytes in the CNS, supporting a role for this family of cytokines in astrocyte differentiation (Ware et al., 1995). However, IL-6 deficient mice do not have constitutive deficits in the numbers of astrocytes, although they appear to have reduced activation in response to injury (Klein et al., 1997).

IL-6 also has a direct effect on adult or neonatally derived NSCs in vitro, increasing astrocyte production and decreasing neuron production (Monje et al., 2003; Nakanishi et al., 2007). Blocking IL-6 in media conditioned by normal microglia inhibits the astrocyte-inducing properties of the conditioned media (Nakanishi et al., 2007). Furthermore, the reduction of neurogenesis caused by LPS-activated microglial conditioned media is attenuated by blocking IL-6 (Monje et al., 2003).

In vivo, there is little direct evidence linking IL-6 production with alterations in neurogenesis or gliogenesis observed during disease. However, mice with chronic overproduction of IL-6 by astrocytes demonstrate a reduction in hippocampal neurogenesis (Vallieres et al., 2002). Although profound astrogliosis was observed in the hippocampus, it did not appear that NSCs were differentiating into astrocytes more frequently in IL-6 overproducing hippocampi (Vallieres et al., 2002). This could provide support for a recent hypothesis which suggested that gp130 signaling does not promote commitment of NSCs to a glial fate, but rather promotes astrocyte differentiation from an already committed glial progenitor (Shimazaki et al., 2001). The role of IL-6 in disease induced changes in neurogenesis warrants further study.

IL-1β

The IL-1 family of cytokines is known primarily for its role in pro-inflammatory responses, but recent emerging evidence suggests it has interesting roles in normal learning and memory as well as changes induced by inflammation and stress (McAfoose and Baune, 2009). The strongest evidence for an anti-neurogenic effect of IL-1 comes from studies of animal models of depression. Chronic mild stress of animals induces depression-like behaviors and decreases in neurogenesis in the hippocampus, both of which are dependent on IL-1β (Goshen et al., 2008; Koo and Duman, 2008). Treatment of mice with IL-1β either intracerebroventricularly (icv) or subcutaneously is sufficient to decrease hippocampal neurogenesis (Goshen et al., 2008; Koo and Duman, 2008). However, mice over expressing soluble IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) which blocks normal IL-1 signaling in the brain also show decreased neurogenesis in the hippocampus, both constitutively and following seizure, and deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory (Goshen et al., 2007; Spulber et al., 2008). These results suggest that constitutive IL-1 signaling is important for normal hippocampal neurogenesis and function. It appears that responses to IL-1β are highly dose dependent, as low doses of IL-1β infused icv increase performance on hippocampal-dependent tasks while high doses inhibit performance (Goshen et al., 2007).

Summary

The complexities of immune states that accompany neurological disease or injury make it difficult to draw concise conclusions about immune signaling and the effects on neural stem cells. In the end, the specific therapeutic or regenerative goal will define whether native immune signaling in a given context is “bad” or “good”. One consistent finding is that the acute innate proinflammatory signaling cascade strongly inhibits the production and retention of new neurons in the adult brain. At the same time, this signaling appears to favor the recruitment and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, a valuable natural component of the injury response. Many vertebrate species are able to fully regenerate lost brain tissue and the reason why neurogenesis is so strongly inhibited in mammals remains obscure but immune signaling seems a likely contributor to the phenomenon. Though speculative, evolutionary pressures may have selected for injury response mechanisms that favor remyelination and rescue of pre-existing neural networks over the formation of entirely new networks. The refinement that occurs over years of learning and adaptation within higher order adult neural networks would be absent in newly generated networks. In one sense, the consequences of complete neural regeneration may actually be loss of function – at least until the new networks are “re-trained” by subsequent experience and become usefully integrated within the pre-existing networks. In childhood, functional refinement takes years, perhaps even two decades, before many neural networks achieve their peak capabilities. One is left wondering if aggressive regenerative approaches are realistic goals for all diseases if such time frames are needed to realize an improvement. Obviously, this is highly speculative since even experimental models have yet to achieve this level of regeneration but it is also a notion worth holding in reserve as we begin to interpret the short term outcomes following the aggressive re-direction of NSCs into a neuronal fate in experimental models.

Despite the uncertainties, the failure of the brain to natively regenerate and the possibility that we might leverage stem cell biology to overcome this failure remains a central driving force in NSC research. Here, the injury environment and related immune signaling are facts of life that must be addressed and future studies can no longer rely on the naïve supposition that the brain will efficiently utilize injected stem cells as substrates for neural network regeneration. It is increasingly obvious that the CNS is not able to efficiently generate replacement neurons without aggressive interventions that overcome the natural inhibition of neurogenesis within the injured or diseased CNS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Pamela A. Carpentier, Email: pcarpent@stanford.edu.

Theo D. Palmer, Email: tpalmer@stanford.edu.

Reference List

- Aarum J, Sandberg K, Haeberlein SL, Persson MA. Migration and differentiation of neural precursor cells can be directed by microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15983–15988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237050100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agresti C, D'Urso D, Levi G. Reversible inhibitory effects of interferon-gamma and tumour necrosis factor-alpha on oligodendroglial lineage cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1106–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonowiz M, Einstein O, Fainstein N, Lassmann H, Reubinoff B, Ben-Hur T. Neuroprotective effect of transplanted human embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursors in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews T, Zhang P, Bhat NR. TNFalpha potentiates IFNgamma-induced cell death in oligodendrocyte progenitors. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:574–583. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981201)54:5<574::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett HA, Mason J, Marino M, Suzuki K, Matsushima GK, Ting JP. TNF alpha promotes proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitors and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nn738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med. 2002;8:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nm747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Carpentier PA, McMahon EJ, Begolka WS, Miller SD. Innate and adaptive immune responses of the central nervous system. Crit Rev Immunol. 2006;26:149–188. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SA, Baker KA, Hagg T. Dopaminergic nigrostriatal projections regulate neural precursor proliferation in the adult mouse subventricular zone. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:575–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos GN, Moriya T, Inui F, Katura T, Nakahata N. Involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 in lipopolysaccharide-induced impairment of the newborn cell survival in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2008;155:454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Ben-Menachem O, Furer V, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Grigoriadis N. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardino L, Agasse F, Silva B, Ferreira R, Grade S, Malva JO. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulates survival, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation in neonatal subventricular zone cell cultures. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2361–2371. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beversdorf DQ, Manning SE, Hillier A, Anderson SL, Nordgren RE, Walters SE, Nagaraja HN, Cooley WC, Gaelic SE, Bauman ML. Timing of prenatal stressors and autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-5037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R, Steinman L. Innate and adaptive autoimmunity directed to the central nervous system. Neuron. 2009;(this issue) doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumcke I, Schewe JC, Normann S, Brustle O, Schramm J, Elger CE, Wiestler OD. Increase of nestin-immunoreactive neural precursor cells in the dentate gyrus of pediatric patients with early-onset temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2001;11:311–321. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonde S, Ekdahl CT, Lindvall O. Long-term neuronal replacement in adult rat hippocampus after status epilepticus despite chronic inflammation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:965–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges K, Gearing M, McDermott DL, Smith AB, Almonte AG, Wainer BH, Dingledine R. Neuronal and glial pathological changes during epileptogenesis in the mouse pilocarpine model. Exp Neurol. 2003;182:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borta A, Hoglinger GU. Dopamine and adult neurogenesis. J Neurochem. 2007;100:587–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger LM. Immune proteins in brain development and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2009;(This issue) doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS, Schaefer CA, Wyatt RJ, Goetz R, Begg MD, Gorman JM, Susser ES. Maternal exposure to respiratory infections and adult schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a prospective birth cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:287–295. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck A, Kurki T, Kaasinen V, Vahlberg T, Rinne JO. Hippocampal and prefrontal atrophy in patients with early non-demented Parkinson's disease is related to cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1467–1469. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bsibsi M, Ravid R, Gveric D, van Noort JM. Broad expression of Toll-like receptors in the human central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1013–1021. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.11.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter MS, Yamane M, Coleman BS, Ormerod BK, Chin JT, Palmer T, Wyss-Coray T. Chronically increased transforming growth factor-beta1 strongly inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:154–164. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, Landa G, Talpalar AE, Pluchino S, Martino G, Schwartz M. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006a;31:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, Landa G, Talpalar AE, Pluchino S, Martino G, Schwartz M. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006b;31:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacci E, Claasen JH, Kokaia Z. Microglia-derived tumor necrosis factor-alpha exaggerates death of newborn hippocampal progenitor cells in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:789–797. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Pan ZL, Pang Y, Evans OB, Rhodes PG. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysaccharide administration. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:64–72. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Gould E. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1994;61:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST. Themes and strategies for studying the biology of stroke recovery in the poststroke epoch. Stroke. 2008;39:1380–1388. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.499962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Palmer TD. Cellular repair of CNS disorders: an immunological perspective. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R84–R92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu K, Kim M, Chae SH, Jeong SW, Kang KS, Jung KH, Kim J, Kim YJ, Kang L, Kim SU, Yoon BW. Distribution and in situ proliferation patterns of intravenously injected immortalized human neural stem-like cells in rats with focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Res. 2004;50:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corriveau RA, Huh GS, Shatz CJ. Regulation of class I MHC gene expression in the developing and mature CNS by neural activity. Neuron. 1998;21:505–520. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covacu R, Arvidsson L, Andersson A, Khademi M, Erlandsson-Harris H, Harris RA, Svensson MA, Olsson T, Brundin L. TLR activation induces TNF-alpha production from adult neural stem/progenitor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:6889–6895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayer AG, Cleaver KM, Abouantoun T, Cameron HA. New GABAergic interneurons in the adult neocortex and striatum are generated from different precursors. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:415–427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Singla S, Toda H, Monje M, Palmer TD, Malenka RC. Excitation-neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron. 2004;42:535–552. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deverman BE, Patterson PH. Cytokines and CNS development. Neuron. 2009;(This issue) doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, Goland R, Wichterle H, Henderson CE, Eggan K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Kang E, Liu CY, Ming GL, Song H. Development of neural stem cell in the adult brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA, Svendsen CN. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009b;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA, Svendsen CN. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009a;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein O, Fainstein N, Vaknin I, Mizrachi-Kol R, Reihartz E, Grigoriadis N, Lavon I, Baniyash M, Lassmann H, Ben-Hur T. Neural precursors attenuate autoimmune encephalomyelitis by peripheral immunosuppression. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:209–218. doi: 10.1002/ana.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Claasen JH, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234031100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Chrousos GP. Stress hormones, proinflammatory and antiinflammatory cytokines, and autoimmunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966:290–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman L, Susser E. XXX. Neuron. 2009;(this issue) doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley JG, Mitchell BD, Kempermann G, Macklis JD. Adult neurogenesis and repair of the adult CNS with neural progenitors, precursors, and stem cells. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:321–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote AK, Blakemore WF. Inflammation stimulates remyelination in areas of chronic demyelination. Brain. 2005;128:528–539. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara Y, Tanaka N, Ishida O, Fujimoto Y, Murakami T, Kajihara H, Yasunaga Y, Ochi M. Intravenously injected neural progenitor cells of transgenic rats can migrate to the injured spinal cord and differentiate into neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Neurosci Lett. 2004;366:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryelewicz T, Styczynska M, Luczywek E, Barczak A, Pfeffer A, Androsiuk W, Chodakowska-Zebrowska M, Wasiak B, Peplonska B, Barcikowska M. The rate of conversion of mild cognitive impairment to dementia: predictive role of depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:563–567. doi: 10.1002/gps.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glezer I, Lapointe A, Rivest S. Innate immunity triggers oligodendrocyte progenitor reactivity and confines damages to brain injuries. FASEB J. 2006;20:750–752. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5234fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ounallah-Saad H, Renbaum P, Zalzstein Y, Ben-Hur T, Levy-Lahad E, Yirmiya R. A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattiangady B, Rao MS, Shetty AK. Chronic temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with severely declined dentate neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:473–490. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. Implications of decreased hippocampal neurogenesis in chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49 5:26–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. Olfaction in neurodegenerative disorder. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;63:133–151. doi: 10.1159/000093759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldmann U, Thored P, Claasen JH, Arvidsson A, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. TNF-alpha antibody infusion impairs survival of stroke-generated neuroblasts in adult rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn BD, Palmer TD, Steinberg GK. Neurogenesis in rats after focal cerebral ischemia is enhanced by indomethacin. Stroke. 2005b;36:2718–2724. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190020.30282.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn BD, Palmer TD, Steinberg GK. Neurogenesis in rats after focal cerebral ischemia is enhanced by indomethacin. Stroke. 2005a;36:2718–2724. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190020.30282.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglinger GU, Rizk P, Muriel MP, Duyckaerts C, Oertel WH, Caille I, Hirsch EC. Dopamine depletion impairs precursor cell proliferation in Parkinson disease. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:726–735. doi: 10.1038/nn1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori J, Ng TF, Shatos M, Klassen H, Streilein JW, Young MJ. Neural progenitor cells lack immunogenicity and resist destruction as allografts. Stem Cells. 2003;21:405–416. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-4-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou SW, Wang YQ, Xu M, Shen DH, Wang JJ, Huang F, Yu Z, Sun FY. Functional integration of newly generated neurons into striatum after cerebral ischemia in the adult rat brain. Stroke. 2008;39:2837–2844. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]