It took no time at all for Dr. Khaled El Emam’s colleague to identify an infant who had been a patient at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa.

But there was a major problem: The colleague had identified the infant from a prescription record and discharge data that was believed to be anonymous or, in privacy jargon, “de-identified.”

“We asked if anyone in the office knew a child who had been admitted to CHEO during the period [of the data set]. Somebody said yes, my neighbour’s one-year-old girl, at this postal code, around this time. We re-identified her and found all her drugs and her diagnosis,” says Dr. El Emam, a Canada research chair in electronic health information at the University of Ottawa’s faculty of medicine.

The data sets had been requested in mid-2008 by Brogan Inc., a private Ottawa-based commercial research firm. The company indicated that the same data had already been obtained from 100 hospitals across Canada, El Emam says.

“Without a formal analysis of the risk of re-identification, assurances of data anonymity may not be accurate,” he stated in an recent article detailing the episode (Can J Hosp Pharm 2009; 62:307–19).

The increase in secondary use of health care data is forcing institutions to become more cognizant of privacy issues, El Emam says. Data can be used as a revenue source, for health research (in areas such as postmarket surveillance of drugs), or to facilitate management and improve patient care, he adds. But because obtaining consent from patients is not possible with secondary use of health care data, the only privacy safeguard is de-identification.

In the United Kingdom, the electronic medical record system was built to facilitate the use of data for research, he adds. Canada, by contrast, must retrofit its health records to ensure privacy.

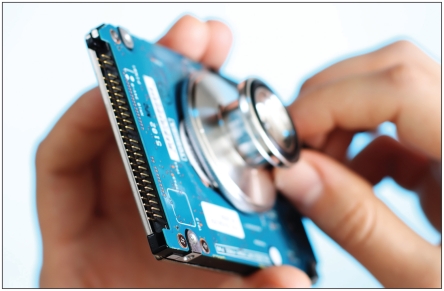

Staff at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario were readily able to identify an infant from prescription and discharge data that was believed to be anonymous.

El Emam’s team “generalized” data provided to Brogan Inc. by, for example, including region instead of a full postal code, age in weeks instead of days and quarter and year of admission instead of day, month and year.

In exchange for providing the prescription and discharge data, Brogan will provide CHEO with benchmarking information comparing it with other pediatric hospitals on important issues such as “finding out what drugs are used for what purposes,” dosage, length of stay and health outcomes, El Eman says. Under the agreement, Brogan Inc. cannot resell the raw data from CHEO, although it could produce analyses and reports.

El Emam says CHEO is eager to obtain benchmarked information since “there aren’t many studies on the right dosage for particular drugs for children” and between 60%–70% of drugs are now prescribed to children on an “off label” basis because few pharmaceuticals are tested on children before being marketed.

“Generally speaking, hospitals are really horrible at using data. They have a lot of data sets but have never integrated them,” says El Eman. “Very few hospitals are managed by data.”

Tom Brogan, president of Brogan Inc., says there is “zero” likelihood that any information that leaves his company can allow a patient to be identified.

Any employee discovered trying to re-identify patients would be immediately fired, adds Brogan, who compares his firm’s statistical reports to those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information and the Toronto, Ontario-based Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

The firm also brokers prescription drug information obtained from public drug plans, insurance companies and pharmacies, Brogan adds. The company began collecting hospital data five years ago and has taken “extraordinary measures” to clean up and standardize the information.

But aggregating the data is “an unbelievable nightmare” because there are so many different ways that information such as date of birth or reasons for admission are entered, Brogan says.