Abstract

In Pakistan more than 10 million people are living with Hepatitis C virus (HCV), with high morbidity and mortality. This article reviews the prevalence, genotypes and factors associated with HCV infection in the Pakistani population. A literature search was performed by using the keywords; HCV prevalence, genotypes and risk factors in a Pakistani population, in Pubmed, PakMediNet and Google scholar. Ninety-one different studies dating from 1994 to May 2009 were included in this study, and weighted mean and standard error of each population group was calculated. Percentage prevalence of HCV was 4.95% ± 0.53% in the general adult population, 1.72% ± 0.24% in the pediatric population and 3.64% ± 0.31% in a young population applying for recruitment, whereas a very high 57% ± 17.7% prevalence was observed in injecting drug users and 48.67% ± 1.75% in a multi-transfused population. Most prevalent genotype of HCV was 3a. HCV prevalence was moderate in the general population but very high in injecting drug users and multi-transfused populations. This data suggests that the major contributing factors towards increased HCV prevalence include unchecked blood transfusions and reuse of injection syringes. Awareness programs are required to decrease the future burden of HCV in the Pakistani population.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Prevalence, Genotypes, Blood transfusions, Injections

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was discovered in 1989 as the major causative agent of non-A, non-B hepatitis[1]. It belongs to the Flaviviridae family and is a plus-stranded RNA virus[2]. About 200 million people are infected with HCV worldwide, which covers about 3.3% of the world’s population[3,4]. HCV infection leads to chronic hepatitis in 50% to 80% of individuals[5]. It was estimated by the WHO in 2004 that the annual deaths due to liver cancer caused by HCV and cirrhosis were 308 000 and 785 000 respectively[6].

Pakistan is a developing country of 170 million people with low health and educational standards. According to the human development index of the United Nations, it was ranked 134th out 174 countries[7]. In Pakistan 10 million people are presumed to be infected with HCV[8]. Public health authorities are creating awareness about hepatitis through print and electronic media[9], but still tremendous efforts are required to increase the awareness regarding various risk factors involved in HCV transmission. In developing countries, due to non-implementation of international standards regarding blood transfusion, reuse of needles for ear and nose piercing, reuse of syringes, injecting drug users, tattooing, shaving from barbers, unsterilized dental and surgical instruments are the main source of transmission of HCV. This article briefly presents the prevalence, genotypes and risk factors associated with HCV transmission in the Pakistani population.

LITERATURE SEARCH

Articles were searched for in Pubmed, Google scholar and PakMediNet (for non-indexed Pakistani journals), by using the key words; HCV in Pakistan, prevalence of HCV in Pakistan, epidemiological patterns of HCV in Pakistan, HCV in multi-transfused Pakistani population, HCV in general Pakistani population, HCV in Pakistani injecting drug users (IDUs) population, HCV in Pakistani health care workers, sexual transmission of HCV, injection use in Pakistan, blood banks/transfusion in Pakistan, awareness about HCV in Pakistani population and HCV genotypes in Pakistan. Inclusion criteria entailed the studies demonstrating the prevalence, genotypes and risk factors of HCV in the Pakistani population while studies with incomplete references were excluded. Two hundred and eighty-one different articles/abstracts/reports were obtained from the literature search, out of which 91, published from 1994 to May 2009, were included in this study.

ANALYSIS

Table 1 includes various reports showing the percentage prevalence of HCV in different groups. Weighted mean of each population was calculated by using the formula:

|

Table 1.

Percentage prevalence of HCV among different communities in Pakistan

| Population type | Author | Region | Methods | Population size | HCV (%) |

| General population | Luby et al[10], 1997 | Hafizabad | RIBA | 309 | 6.50 |

| Parker et al[11], 2001 | Lahore | EIA | 417 | 6.70 | |

| Khokhar et al[12], 2004 | Islamabad | ELISA | 47 538 | 5.31 | |

| Muhammad et al[13], 2005 | Buner | ELISA | 16 400 | 4.57 | |

| Hashim et al[14], 2005 | Attock | ELISA | 4552 | 4.00 | |

| Zaman et al[15], 2006 | Bahawalpur | ICT | 6815 | 4.41 | |

| Alam et al[16], 2006 | Central Punjab | ELISA, ICT | 2038 | 4.41 | |

| Chaudhary et al[17], 2007 | Rawalpindi | MEIA | 1428 | 2.52 | |

| Hakim et al[18], 2008 | Karachi | ELISA,ICT,PCR | 3820 | 5.20 | |

| Tunveer et al[19], 2008 | Lahore | ICT | 203 | 1.48 | |

| Pediatric population | Agboatwalla et al[20], 1994 | Karachi | ELISA | 236 | 0.44 |

| Khan et al[21], 1996 | Lahore | EIA,RIBA | 538 | 4.09 | |

| Parker et al[22], 1999 | Lahore | ELISA | 538 | 1.30 | |

| Hyder et al[23], 2001 | Lahore | ELISA | 171 | 0.58 | |

| Jafri et al[24], 2006 | Karachi | ELISA | 3533 | 1.60 | |

| Aziz et al[25], 2007 | Karachi | EIA | 380 | 1.40 | |

| Recruitment | Ali et al[26], 2002 | Rawalpindi | ICT | 5371 | 3.29 |

| Zakaria et al[27], 2003 | Karachi | ICT-ELISA | 966 | 2.20 | |

| Masood et al[28], 2005 | Lahore | ELISA | 4552 | 4 | |

| Mirza et al[29], 2006 | Mardan | ELISA | 15 550 | 3.69 | |

| Sharif et al[30], 2006 | Risalpur | ELISA | 2558 | 3.40 | |

| Alam et al[31], 2006 | Sargodha | unknown | 2038 | 4.41 | |

| Pregnant women | Zafar et al[33], 2001 | Lahore | PCR | 300 | 4 |

| Khokhar et al[34], 2004 | Islamabad | ELISA | 503 | 4.80 | |

| Jaffery et al[35], 2005 | Islamabad | ELISA,PCR | 947 | 3.27 | |

| Yousfani et al[36], 2006 | Hyderabad | ICT, ELISA | 103 | 16.50 | |

| Blood donors | Mujeeb et al[37], 1996 | Karachi | EIA | 839 | 2.40 |

| Bhatti et al[38], 1996 | Rawalpindi | EIA | 760 | 4.80 | |

| Mujeeb et al[39], 2000 | Karachi | ELISA | 7047 | 2.40 | |

| Ali et al[40], 2003 | Quetta | ELISA | 1500 | 1.87 | |

| Asif et al[41], 2004 | Islamabad | MEIA | 3430 | 5.14 | |

| Ahmad et al[42], 2004 | Peshawar | MEIA | 4000 | 2.20 | |

| Zaidi et al[43], 2004 | Peshawar | ELISA | 49 037 | 2.60 | |

| Chaudry et al[44], 2005 | Lahore | ELISA | 890 | 6.06 | |

| Abdul Mujeeb et al[45], 2006 | Karachi | ELISA | 7325 | 3.60 | |

| Chaudhary et al[17], 2007 | Rawalpindi | MEIA | 1428 | 2.52 | |

| Sultan et al[46], 2007 | Different Areas | EIA | 41 498 | 4.99 | |

| Khattak et al[47], 2008 | Different Areas | ELISA | 103 858 | 4 | |

| IDU | Kuo et al[52], 2006 | Lahore | ELISA | 351 | 88 |

| Achakzai et al[53], 2007 | Quetta | ELISA | 50 | 60 | |

| Altaf et al[54], 2009 | Karachi | ELISA | 161 | 94 | |

| Platt et al[55], 2009 | Abbottabad | ELISA | 102 | 8 | |

| Platt et al[55], 2009 | Rawalpindi | ELISA | 302 | 17.30 | |

| Thalassemic | Bhatti et al[58], 1995 | Rawalpindi | ELISA | 35 | 60 |

| Muhammad et al[59], 2003 | Peshawar | ELISA | 80 | 36 | |

| Shah et al[60], 2005 | NWFP | ELISA | 250 | 57 | |

| Hussain et al[61], 2008 | Islamabad/Peshawar | ELISA | 180 | 41.70 | |

| Hemophilia | Hussain et al[62], 2003 | Peshawar | ELISA | 40 | 25 |

| Malik et al[57], 2006 | Lahore | ELISA | 100 | 56 | |

| Health care workers | Mujeeb et al[64], 1998 | Karachi | EIA | 114 | 4.40 |

| Aziz et al[65], 2002 | Karachi | ELISA | 250 | 5.60 | |

| Sexual/spousal | Irfan et al[70], 2004 | Islamabad | PCR | 23 | 4.30 |

| Kumar et al[71], 2004 | Karachi | MEIA | 50 | 18 | |

| Khokher et al[72], 2005 | Islamabad | ELISA | 227 | 4.40 | |

| Qureshi et al[73], 2007 | Karachi | EIA/PCR | 153 | 38 |

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; RIBA: Recombinant strip immunosorbent assay; ICT: Immunochromatographic test; ELISA: Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; MEIA: Micro-enzyme immunoassay; EIA: Enzyme immunoassay; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

Standard error of mean was calculated by using the formula:

|

Results of each population group are presented in the form of mean ± SE with 95% confidence interval.

HCV PREVALENCE IN VARIOUS GROUPS

General population

Ten different studies showed that the percent prevalence of HCV in the general adult population was 4.95% ± 0.53%[10-19], while six studies showed a percent prevalence of 1.72% ± 0.24% in the pediatric population[20-25]. In Pakistan, military recruits are screened for HCV before induction; six different studies showed a percent prevalence of 3.64% ± 0.31% in candidates for military recruitment[26-31]. About 5% of infants obtained HCV infection transmitted from a mother carrying both HCV antibody and HCV RNA[32]; four studies in pregnant women showed the percent prevalence to be 4.54% ± 3.5%[33-36]. Volunteer blood donors are the healthiest population in a community and HCV prevalence in these individuals is a true reflector of a general population’s health[9]; twelve different studies showed the percent prevalence to be 3.78% ± 0.41% in blood donors[17,37-47].

IDUs

It was estimated that there were about 5 million drug users in Pakistan, out of which 15% were regular IDUs[48]. There has been an increased shift among addicts from inhalatory to injectable drugs due to decrease in quality and availability of heroin (common inhalatory drug used in Afghanistan and Pakistan)[49]. The effect of injecting drugs is more intense and satisfying, and young drug users who switch over to injectables usually adopt it as the main route of their drug administration[50]. Approximately 50% of IDUs reported by Altaf et al[51] in 2007 were in a treatment program; the majority of them wanted to get rid of their addiction but could not do so due to non availability or high charges by rehabilitation centers. The main reason for relapse was the economic crisis which most addicts suffer because the rehabilitation centers are not involved in the development of vocational skills among addicts. Four different reports showed a high 57% ± 17.7% prevalence of HCV among the IDUs[52-55].

Multi-transfused population

Thalassemic and hemophilic patients require life-long blood transfusions, so it is necessary to obtain screened blood from a reputable source, because the multi-transfused population is more prone to blood-borne pathogens. Arif et al[56] reported that only 15.8% of parents of thalassemic children knew the importance of blood screening. Six different reports showed an HCV percent prevalence of 48.67% ± 1.75% among the thalassemic and hemophilic population[56-62].

Health care workers

Health care workers are at high risk of HCV infection because they are dealing with blood, blood-related products and instruments which may carry transmittable pathogens. Hamid et al[63] reported that recapping of syringes is the key factor for receiving needle stick injuries in health care workers and that transmission of HCV by needle stick injury ranges from 2% to 10%. Two different reports showed an HCV percent prevalence of 5.2% ± 0.63% in health care workers[64,65].

Sexual transmission

It has been reported from the US that up to 20% of new HCV infections are due to sexual activity[66]. Two different reports from the USA and Congo indicate low HCV prevalence among commercial sex workers[67,68]. The main problems in Pakistan are illiteracy, lack of awareness about sexually transmitted diseases and low use of condoms among the sex workers. Saleem et al[69] reported in 2005 that 17% of female sex workers, 3% of male sex workers and 4% of hijras (transgender men) consistently used condoms during the previous month; 67% of female sex workers were illiterate, 34% of female sex workers were suffering from sexually transmitted infections. Homosexual activities were very high among street children who are sexually victimized or indulge in such activities; later on they adopt commercial sex in order to raise their income. Condom usage among the male homosexual population was very low. Four different studies showed an interspousal percent prevalence of 17.24% ± 7.98%[70-73].

RISK FACTORS

Unsafe and unnecessary needles

The reuse of syringes and needles was a major factor contributing towards increased HCV prevalence[74,75]. It was reported that there are several small groups involved in recycling and repacking of used unsterilized syringes, which were available in various drug stores. It was difficult for the public to differentiate between new sterilized syringes and recycled unsterilized syringes[76]. Janjua et al[77] reported that 68% of individuals received injections during the previous three months in Digri and Mirpur khas, two districts of Pakistan, out of which only 54% were from freshly opened syringes. The incidence of sharing of injection equipment for the last injection was 8.5% in Hyderabad and 33.6% in Sukkur[54].

In Pakistan, the number of estimated injections per person per year ranged from 8.2 to 13.6, which was the highest among developing countries, out of which 94.2% were unnecessary[51]. Household members who received four injections per year were 11.4% more prone to HCV infection than who did not receive injection[78]. Khan et al[74] reported that if both oral and injectable medicine were equally effective, 44% of the Pakistani population preferred injectable medicine.

In 2000, the WHO recommended that countries should implement strategies to change the behavior of health care workers and patients in order to decrease the over-use of injections, to ensure the practice of sterile syringes and needles, and to properly destroy sharp waste after use[79]. It was reported that 59% of syringes were dumped into the general waste and not properly disposed of in the healthcare waste. Scavengers seeking valuable things from the waste are at high risk of receiving needle stick injuries from contaminated needles[76].

Blood transfusion

People in developing countries are mostly anemic, and are more prone to traumatic injuries and obstetric complications. Blood transfusion in these situations is life-saving. If blood is not properly stored or is carrying blood-borne pathogens, then the situation becomes more complicated. According to the WHO office in Pakistan about 1.2 to 1.5 million transfusions are carried out annually in Pakistan[80]. In 2000, Luby et al[81] reported that 50% of blood banks in Karachi recruited paid donors, 25% of donations were from volunteer donors and only 23% of the blood banks screened for HCV while 29% of them were storing blood outside the WHO recommended temperature.

In developing countries, blood transfusion is still a problem due to lack of organized infrastructure, continuous supply of electricity, and properly trained and educated staff. In Pakistan the main source of blood donations are replacement donors and the majority of these are friends and relatives of the patient. These donors donate blood due to fear of death of a relative, chance of further complication of disease or under family pressure. These donors mostly hide their health conditions from their relatives. Selection of donor and their proper screening are key factors to ensure safe transfusion. Safe blood donors are those whose donations are repeatedly negative on screening[17]. Sixty-six percent of Pakistanis are residents of rural areas where there is less access to blood transfusion services. To provide proper transfusion facilities to underdeveloped areas requires economic growth. Efforts are required to eliminate the transfusions from paid donors, to improve the safety of the blood supply[81]. These conditions can be overcome by development of a fair and organized system of blood screening and transfusion.

Barbers

In third world countries like Pakistan, most of the barbers are illiterate and unaware of transmission of infectious agents through the repeated use of razors and scissors for different customers without sterilizing them first[82]. Janjua and Nizamy reported that only 13% of the barber community knew that hepatitis is a liver disease and that it could be transmitted by contaminated razors; 11.4% of them were cleaning razors with antiseptic solution while 46% of them were re-using razors[83]. Recent reports suggested that only 42% knew about hepatitis, 90% did not wash hands, 80% were not changing aprons and 66% were not changing towels after each customer. Circumcision is a very important religious procedure performed during early infancy both in rural and urban areas, and the barber community performing this procedure are mostly unaware of transmission of hepatitis by contaminated instruments[84]. Bari et al[85] identified the risk factors involved in transmission of HCV and reported that 70% and 48% of HCV patients had histories of facial and armpit shaving from barbers respectively.

Awareness

In the Pakistani population there was moderate knowledge about HCV infection whereas awareness about various HCV risk factors was very low[31,86,87]. In a survey conducted at a family medicine clinic in Karachi, most of the participants had some educational background and were living in Karachi city. It was reported that 61% of participants believed that HCV was a viral disease, 49% believed that it could be transferred by needles and injections, 5.3% believed that it could be transmitted by ear and nose piercing, and 20.6% knew that it can cause cancer[86]. Kuo et al[52] reported in 2006 that HCV awareness was only 19% in the IDU population of Lahore and Quetta. Zuberi et al[88] reported that knowledge about HCV infection was related to the educational background of the participants. Public awareness programs are required to decrease the future burden of HCV infection in the Pakistani population.

GENOTYPES

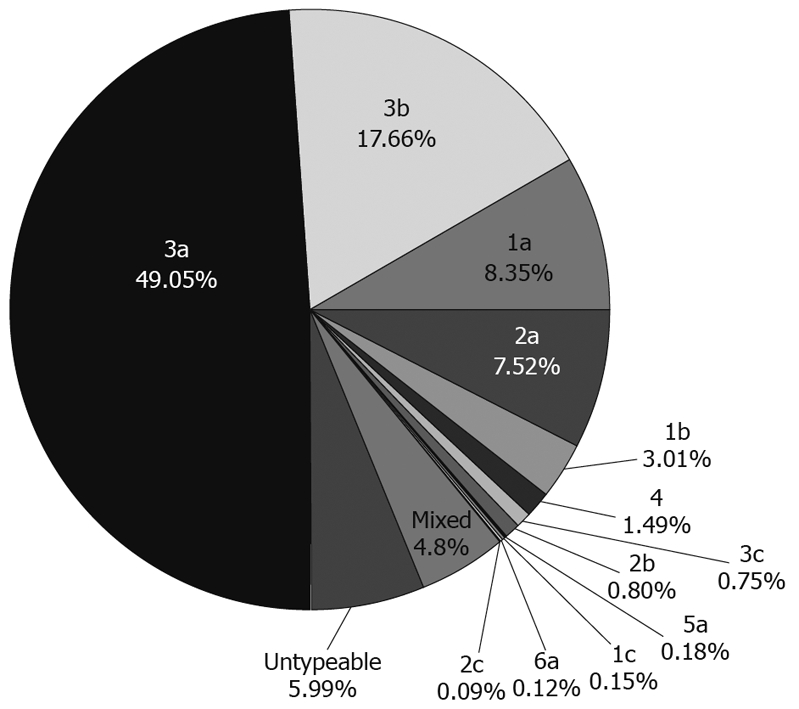

HCV is classified into eleven different genotypes, of which six are the major genotypes and these genotypes are further classified into many subtypes[89,90]. In 1997 it was reported in a small study that 87% of the individuals in Pakistan had genotype 3[91]. In 2004, a panel of 30 top gastroenterologists of the country met at a conference and reported that 75%-90% of HCV patients in Pakistan had genotype 3a[8]. Qazi et al[92] reported in 2006 that 71% of patients had genotype 3 while only 10% had genotype 1. In 2007 it was reported that 81% of individuals had genotype 3 while only 9.5% had genotype 1[93]. Hakim et al[18] reported in 2008 that 51% of HCV patients had genotype 3a; 24% had 3a/3b co-infection and 16% had genotype 3b, while similar results were also reported by Afridi et al[94] who stated that 50% of HCV patients had genotype 3a followed by 3b and 1a. The most detailed study was conducted by Idrees and Riazuddin in 2008, who performed genotyping of 3351 patients and reported that genotype 3a was the most prevalent genotype in Pakistan; their results are summarized in Figure 1[95].

Figure 1.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes in Pakistan (2008)[95].

CONCLUSION

This study reviewed the seroprevalence of HCV among various population groups, along with risk factors and genotypes in Pakistan. HCV prevalence was observed in nearly 5% of the general population which is in parallel with the WHO estimates of HCV in Pakistan. High prevalence was observed in IDUs and the multi-transfused population, suggesting that the reuse of syringes was common among the injecting drug users, and that blood transfusions were not properly screened. Most prevalent genotype of HCV was 3a. The majority of HCV-positive patients had a history of facial and armpit shaving by barbers suggesting that the barbers shop was the key place for viral transmission. Condom usage was very low among the commercial sex workers and there was low awareness about sexually transmitted diseases amongst this group. In Pakistan, the number of estimated injections per person per year was very high because most Pakistanis think that injectable drugs are more efficacious than oral drugs. There was low awareness in people about the various risk factors associated with HCV transmission. Treatment of hepatitis is very expensive and is creating a huge burden on the country’s economy. More emphasis should be given to the preventive measures of the disease in order to decrease the future health and economic burden; these include screened blood transfusions, proper sterilization techniques in clinics and hospitals, use of disposable syringes and razor blades. The government should take aggressive steps to create awareness among the general public by the use of media or by modifying the school syllabus.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Mr. Abdul Shakoor, Assistant Professor, Department of Statistics, Pir Mehr Ali Shah University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi, Pakistan for his help in data analysis.

Footnotes

Supported by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan Grant No. 829, and Pak-US Science and Technology Cooperative Program, entitled “HCV management in Pakistan”

Peer reviewer: Eva Herrmann, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Biomathematics, Saarland University, Faculty of Medicine, Kirrberger Str., 66421 Homburg/Saar, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds , editors. Fields virology. 4th ed, vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2001. pp. 991–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wands JR. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1567–1570. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lausanne. Clinical Update - Debio 025 in Hepatitis C. 2008. Accessed April, 2009. Available from: http://www.debiopharm.com/press-releases/debio-025/clinical-update-debio-025-in-hepatitis-c.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Department of Measurement and Health Information. 2004 Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/bodgbddeathdalyestimates.xls. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report 1996. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid S, Umar M, Alam A, Siddiqui A, Qureshi H, Butt J. PSG consensus statement on management of hepatitis C virus infection--2003. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:146–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhtar S, Rozi S. An autoregressive integrated moving average model for short-term prediction of hepatitis C virus seropositivity among male volunteer blood donors in Karachi, Pakistan. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1607–1612. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luby SP, Qamruddin K, Shah AA, Omair A, Pahsa O, Khan AJ, McCormick JB, Hoodbhouy F, Fisher-Hoch S. The relationship between therapeutic injections and high prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Hafizabad, Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:349–356. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker SP, Khan HI, Cubitt WD. Detection of Antibodies to Hepatitis C Virus in Dried Blood Spot samples from Mothers and Their Offspring in Lahore, Pakistan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:407–411. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2061-2063.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khokhar N, Gill ML, Malik GJ. General seroprevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections in population. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:534–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muhammad N, Jan MA. Frequency of hepatitis "C" in Buner, NWFP. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashim R, Hussain AB, Rehman K. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis-C Virus Antibodies Among Healthy Young Men in Pakistan. Pak J Med Res. 2005:44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaman R. Prevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Viruses in Human Urban Population of Bahawalpur District, Pakistan. J Med Sci. 2006;6:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alam M, Tariq WZ, Akram S, Qureshi TZ. Frequency of Hepatitis B and C in central Punjab. Pak J Pathol. 2006;17:140–141. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhary IA, Samiullah , Khan SS, Masood R, Sardar MA, Mallhi AA. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among the healthy blood donors at Fauji Foundation Hospital Rawalpindi. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakim ST, Kazmi SU, Bagasra O. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Genotypes Among Young Apparently Healthy Females of Karachi-Pakistan. Libyan J Med. 2008:AOP, 071123. doi: 10.4176/071123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tunveer A, Batool K, Qureshi WA. Prevalence of Hepatitis B and C in university of Punjab, Quaid-e-Azam campus, Lahore. ARPN J Agri and Bio Sci. 2008;3:30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agboatwalla M, Isomura S, Miyake K, Yamashita T, Morishita T, Akram DS. Hepatitis A, B and C seroprevalence in Pakistan. Indian J Pediatr. 1994;61:545–549. doi: 10.1007/BF02751716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan HI. A study of seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in mothers and children in Lahore. Pak Ped J. 1996;20:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker SP, Khan HI, Cubitt WD. Detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in dried blood spot samples from mothers and their offspring in Lahore, Pakistan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2061–2063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2061-2063.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyder SN, Hussain W, Aslam M, Sajid M. Seroprevalence of Anti-HCV in asymptomatic children. Pak J Pathol. 2001;12:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jafri W, Jafri N, Yakoob J, Islam M, Tirmizi SF, Jafar T, Akhtar S, Hamid S, Shah HA, Nizami SQ. Hepatitis B and C: prevalence and risk factors associated with seropositivity among children in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aziz S, Muzaffar R, Hafiz S, Abbas Z, Zafar MN, Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis viruses A, C, E, antibodies and hbsag - prevalence and associated risk factors in pediatric communities of karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali N, Khattak J, Anwar M, Tariq W. Z, Nadeem M, Irfan M, Asif M, Hussain AB. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis c anti bodies in young healthy adults. Pak J Pathol. 2002;13:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zakaria M, Ali S, Tariq G. R, Nadeem M. Prevalence of Anti-hepatitis C antibodies and Hepatitis B surface Antigen in healthy male Naval recruits. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2003;53:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masood Z, Jawaid M, Khan RA, Rehman S. Screening for hepatitis B & C: A routine prospective investigation? Pak J Med Sci. 2005;21:455–459. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirza IA, Mirza SH, Irfan S, Siddiqi R, Tariq WUZ, Janjua AS. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in young adults seeking recruitment in armed forces. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2006;56:192–197. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharif BT, Tariq WZ. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in healthy adult male recruits. Pak J Pathol. 2006;17:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alam M, Tariq WZ. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about hepatitis B and C among young healthy males. Pak J Pathol. 2006;17:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conte D, Fraquelli M, Prati D, Colucci A, Minola E. Prevalence and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rate of HCV vertical transmission in a cohort of 15,250 pregnant women. Hepatology. 2000;31:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zafar MAF, Mohsin A, Husain I, Shah AA. Prevalence of Hepatitis C Among Pregnant Women. J Surg Pak. 2001;6:32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khokhar N, Raja KS, Javaid S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and its risk factors in pregnant women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaffery T, Tariq N, Ayub R, Yawar A. Frequency of hepatitis C in pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:716–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yousfani S, Mumtaz F, Memon A, Memon MA, Sikandar R. Antenatal screening for hepatitis B and C virus carrier state at a university hospital. J Lia Uni Med Health Sci. 2006;5:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mujeeb SA, Mehmood K. Prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV infections among family blood donors. Ann Saudi Med. 1996;16:702–703. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1996.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatti FA, Shaheen N, Tariq WZ, Amin A, Saleem M. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in blood donors in Northern Pakistan. Pak Armed Forces Med J. 1996;46:91–92. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mujeeb SA, Shahab S, Hyder AA. Geographical display of health information: study of hepatitis C infection in Karachi, Pakistan. Public Health. 2000;114:413–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali N, Nadeem M, Qamar A, Qureshi AH, Ejaz A. Frequency of hepatitis C virus antibodies in blood donors in combined military hospital, Quetta. Pak J Med Sci. 2003;19:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asif N, Khokhar N, Ilahi F. Seroprevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV infection among volunteer non-renumerated and replacement donors in Northern Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2004;20:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmad J, Taj AS, Rehim A, Shah A, Rehmen M. Frequency of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in healthy blood donors of NWFP: a single center experience. J Post Med Inst. 2004;18:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaidi A, Tariq WZ, Haider KA, Ali L, Sattar A, Faqeer F, Rehman S. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in healthy blood donors in Northwest of Pakistan. Pak J Pathol. 2004;15:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaudry NT, Jameel W, Ihsan I, Nasreen S. Hepatitis C. Prof Med J. 2005;12:364–367. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abdul Mujeeb S, Nanan D, Sabir S, Altaf A, Kadir M. Hepatitis B and C infection in first-time blood donors in Karachi--a possible subgroup for sentinel surveillance. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sultan F, Mehmood T, Mahmood MT. Infectious pathogens in volunteer and replacement blood donors in Pakistan: a ten-year experience. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khattak MN, Akhtar S, Mahmud S, Roshan TM. Factors influencing Hepatitis C virus sero-prevalence among blood donors in north west Pakistan. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29:207–225. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention. Global Illicit Drug Trend. 2002. New York: United Nations; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shah SA, Altaf A. Prevention and control of HIV/AIDS among injection drug users in Pakistan: a great challenge. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:S75–S76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emmanuel F, Attarad A. Correlates of injection use of synthetic drugs among drug users in Pakistan: a case controlled study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altaf A, Janjua NZ, Hutin Y. The cost of unsafe injections in Pakistan and challenges for prevention program. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;16:622–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuo I, ul-Hasan S, Galai N, Thomas DL, Zafar T, Ahmed MA, Strathdee SA. High HCV seroprevalence and HIV drug use risk behaviors among injection drug users in Pakistan. Harm Reduct J. 2006;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achakzai M, Kassi M, Kasi PM. Seroprevalences and co-infections of HIV, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus in injecting drug users in Quetta, Pakistan. Trop Doct. 2007;37:43–45. doi: 10.1258/004947507779951989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altaf A, Saleem N, Abbas S, Muzaffar R. High prevalence of HIV infection among injection drug users (IDUs) in Hyderabad and Sukkur, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:136–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Platt L, Vickerman P, Collumbien M, Hasan S, Lalji N, Mayhew S, Muzaffar R, Andreasen A, Hawkes S. Prevalence of HIV, HCV and sexually transmitted infections among injecting drug users in Rawalpindi and Abbottabad, Pakistan: evidence for an emerging injection-related HIV epidemic. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85 Suppl 2:ii17–ii22. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arif F, Fayyaz J, Hamid A. Awareness among parents of children with thalassemia major. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:621–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malik N, Hussain Z. Markers of viral hepatitis in hemophiliacs. Biomedica. 2006;22:48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatti FA, Amin M, Saleem M. Prevalence of anti body to hepatitis C virus in Pakistani thalassaemics by particle agglutination test utilizing C 200 and C22-3 viral antigen coated proteins. J Pak Med Assoc. 1995;45:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muhammad J, Hussain M, Khan MA. Frequency of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C infection in Thalassemic children. Pak Pediatr J. 2003;27:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah SMA, Khan MT, Zahour Ullah, Ashfaq NY. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in multitransfused thalassaemia major patients in North West Frontier Province. Pak J Med Sci. 2005;21:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hussain H, Iqbal R, Khan MH, Iftikhar B, Aziz S, Burki FK. Prevalence of hepatitis C in Beta thalassaemia major. Gomal J Med Sci. 2008;6:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hussain M, Khan MA, Muhammad J, Jan A. Frequency of Hepatitis B and C in hemophiliac children. Pak Pediatr J. 2003;27:157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamid SS, Farooqui B, Rizvi Q, Sultana T, Siddiqui AA. Risk of transmission and features of hepatitis C after needlestick injuries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:63–64. doi: 10.1086/501547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mujeeb SA, Khatri Y, Khanani R. Frequency of parenteral exposure and seroprevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV among operation room personnel. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aziz S, Memon A, Tily HI, Rasheed K, Jehangir K, Quraishy MS. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C amongst health workers of Civil Hospital Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:92–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alter MJ. Hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:88–91. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buffington J, Murray PJ, Schlanger K, Shih L, Badsgard T, Hennessy RR, Wood R, Weisfuse IB, Gunn RA. Low prevalence of Hepatitis C virus antibody in men who have sex with men who do not inject drugs. Pub Health Rep. 2007;122:63–67. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laurent C, Henzel D, Mulanga-Kabeya C, Maertens G, Larouzé B, Delaporte E. Seroepidemiological survey of hepatitis C virus among commercial sex workers and pregnant women in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:872–877. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saleem NH, Adrien A, Razaque A. Risky sexual behavior, knowledge of sexually transmitted infections and treatment utilization among a vulnerable population in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39:642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Irfan A, Arfeen S. Hepatitis C virus infection in spouses. Pak J Med Res. 2004;43:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar N, Sattar RA, Ara J. Frequency of hepatitis C virus in the spouses of HCV positive patients and risk factors for two groups. J Surg Pak. 2004;9:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khokher N, Gill ML, Alam AY. Interspousal transmission of hepatitis c virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:587–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qureshi H, Arif A, Ahmed W, Alam SE. HCV exposure in spouses of the index cases. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:175–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khan AJ, Luby SP, Fikree F, Karim A, Obaid S, Dellawala S, Mirza S, Malik T, Fisher-Hoch S, McCormick JB. Unsafe injections and the transmission of hepatitis B and C in a periurban community in Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:956–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simonsen L, Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Kane M. Unsafe injections in the developing world and transmission of bloodborne pathogens: a review. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:789–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abdul Mujeeb S, Adil MM, Altaf A, Hutin Y, Luby S. Recycling of injection equipment in Pakistan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:145–146. doi: 10.1086/502175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Janjua NZ, Akhtar S, Hutin YJ. Injection use in two districts of Pakistan: implications for disease prevention. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:401–408. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pasha O, Luby SP, Khan AJ, Shah SA, McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Household members of hepatitis C virus-infected people in Hafizabad, Pakistan: infection by injections from health care providers. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123:515–518. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.World Health Organization. Unsafe Injection Practices Having Serious Large-Scale Consequences. Press Release WHO/14. Geneva: WHO; 2000. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 80.WHO country office in Pakistan, blood safety. Accessed April, 2009. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/pakistan/programmeareas_bloodsafety.htm.

- 81.Luby S, Khanani R, Zia M, Vellani Z, Ali M, Qureshi AH, Khan AJ, Abdul Mujeeb S, Shah SA, Fisher-Hoch S. Evaluation of blood bank practices in Karachi, Pakistan, and the government's response. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:217–222. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khaliq AA, Smego RA. Barber shaving and blood-borne disease transmission in developing countries. S Afr Med J. 2005;95:94, 96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Janjua NZ, Nizamy MA. Knowledge and practices of barbers about hepatitis B and C transmission in Rawalpindi and Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:116–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wazir MS, Mehmood S, Ahmed A, Jadoon HR. Awareness among barbers about health hazards associated with their profession. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bari A, Akhtar S, Rahbar MH, Luby SP. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in male adults in Rawalpindi-Islamabad, Pakistan. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:732–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khuwaja AK, Qureshi R, Fatmi Z. Knowledge about hepatitis B and C among patients attending family medicine clinics in Karachi. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8:787–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Talpur AA, Memon NA, Solangi RA, Ghumro AA. Knowledge and attitude of patients towards Hepatitis B and C. Pak J surg. 2007;23:162–165. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zuberi BF, Zuberi FF, Vasvani A, Faisal N, Afsar S, Rehman J, Qamar B, Jaffery B. Appraisal of the knowledge of Internet users of Pakistan regarding hepatitis using on-line survey. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization. Epidemic and pandemic alert and response, Hepatitis c virus. 2003. Accessed April, 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsrlyo2003/en/index2.html. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zein NN, Persing DH. Hepatitis C genotypes: current trends and future implications. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:458–462. doi: 10.4065/71.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shah HA, Jafri W, Malik I, Prescott L, Simmonds P. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes and chronic liver disease in Pakistan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Qazi MA, Fayyaz M, Chaudhry GM, Jamil Aftab, Malik AH, Gardezi AI, Bukhari MH. Hepatitis C virus Genotypes in Bahawalpur. Biomedica. 2006;22:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ahmad N, Asgher M, Shafique M, Qureshi JA. An evidence of high prevalence of Hepatitis C virus in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Afridi S, Naeem M, Hussain A, Kakar N, Babar ME, Ahmad J. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes in Balochistan. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:1511–1514. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Idrees M, Riazuddin S. Frequency distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in different geographical regions of Pakistan and their possible routes of transmission. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]