Abstract

AIM: To compare clinical presentation and ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) sensitivity between intraluminal and infiltrating gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA).

METHODS: This retrospective study evaluated 65 cases of GBCA that were categorized morphologically into the intraluminal-GBCA (n = 37) and infiltrating-GBCA (n = 28) groups. The clinical and laboratory findings, presence of gallstones, gallbladder size, T-staging, nodal status, sensitivity of preoperative US and CT studies, and outcome were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS: There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to female predominance, presence of abdominal pain, serum aminotransferases level, T2-T4 staging, and regional metastatic nodes. Compared with the patients with intraluminal-GBCA, those with infiltrating-GBCA were significantly older (65.49 ± 1.51 years vs 73.07 ± 1.90 years), had a higher frequency of jaundice (3/37 patients vs 13/28 patients) and fever (3/37 patients vs 10/28 patients), higher alkaline phosphatase (119.36 ± 87.80 IU/L vs 220.68 ± 164.84 IU/L) and total bilirubin (1.74 ± 2.87 mg/L vs 3.50 ± 3.51 mg/L) levels, higher frequency of gallstones (12/37 patients vs 22/28 patients), smaller gallbladder size (length, 7.47 ± 1.70 cm vs 6.47 ± 1.83 cm; width, 4.21 ± 1.43 cm vs 2.67 ± 0.93 cm), and greater proportion of patients with < 12 mo survival (16/37 patients vs 18/28 patients). The sensitivity for diagnosing intraluminal-GBCA with and without gallstones was 63.6% and 91.3% by US, and 80% and 100% by CT, respectively. The sensitivity for diagnosing infiltrating-GBCA with and without gallstones was 12.5% and 25% by US, and 71.4% and 75% by CT, respectively.

CONCLUSION: In elderly women exhibiting small gallbladder and gallstones on US, especially those with jaundice, fever, high alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels, CT may reveal concurrent infiltrating-GBCA.

Keywords: Gallbladder neoplasms, Carcinoma, Ultrasound, Computed tomography

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA) is the sixth most common gastrointestinal malignancy in the United States, following cancer of the colon, pancreas, stomach, liver, and esophagus[1,2]. Nevertheless, GBCA is relatively uncommon with an estimated annual incidence of 1 or 2 cases per 100 000 people[2]. The nonspecific nebulous symptoms associated with GBCA make the early diagnosis of this uncommon entity a challenge. Approximately 50% of cases of GBCA are found incidentally during cholecystectomy or surgery for other reasons[3,4]. GBCA is a highly aggressive neoplasm with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%[1-5]. Although most patients present with advanced disease, aggressive radical surgical resection of GBCA has been reported with encouraging results[3-5]. Furthermore, survival of GBCA can be improved if early detection of the tumor can be achieved so that curative resection can be performed. Ultrasound (US) is the main initial diagnostic tool for suspected biliary lesions. It may be helpful for detecting GBCA although the infiltrative morphology of some tumors and the presence of gallstones, inflammation and debris may preclude tumor detection[6-9]. Computed tomography (CT) has been reported as a comprehensive tool for imaging and staging of GBCA[7-11].

To the best of our knowledge, the influence of different tumor morphology on clinical presentation, as well as on US and CT sensitivity of GBCA detection, have not been well studied. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences in clinical presentation and sensitivity of preoperative US and CT assessment between GBCA presenting as an intraluminal mass and an infiltrating tumor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The computer data bank of our hospital was searched for cases from 1995 to 2008 with the index terms “malignant neoplasm of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts” and “malignant neoplasm of gallbladder” (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, clinical modification code = 156, 156.0). The medical records of all patients with these discharge diagnoses were reviewed. Patients who had surgery and pathologically proven GBCA, as well as preoperative US and/or CT were included in this case series. The patients were categorized into two groups according to the gross tumor morphology and histopathological features of the GBCA. The intraluminal-GBCA group comprised patients with intraluminal tumor growths that protruded into the gallbladder lumen, which grossly appeared as polypoid, fungating or large intraluminal masses. The infiltrating-GBCA group consisted of patients with infiltrating carcinomas that appeared grossly as focal or diffuse areas of wall thickening, or induration in the gallbladder wall. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and anonymous nature of the analysis.

Imaging evaluation

Transabdominal US was performed with various scanners including the Aloka SSD-650 (Aloka Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the Acuson 128 XP/10 and Sequoia 512 scanners (Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA) using a 3.5-MHz sector transducer. Abdominal CT was performed using a ProSpeed scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) or a Somatom Plus 4 scanner (Volume Zoom; Siemens, Forchheim, Germany) from the liver dome to the pelvic floor. An intravenous bolus of 85-100 mL iodinated contrast material (60%-76% diatrizoate meglumine) was injected at a rate of 2-3 mL/s via the antecubital vein before scanning. All images were reconstructed at intervals of 5-10 mm. Starting in 2003, all CT images were interpreted on a high resolution monitor (MGD 521MK II; BarcoView, Kortrijk, Belgium) via the picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) system (Centricity Workstation, version 2.0; GE Healthcare). All CT images recorded in hard copy before 2003 were scanned into the PACS system for review, and all measurements were done by applying the tools provided by the Centricity Workstation. A detailed retrospective review of the medical records, US and CT images and pathological findings of each patient was conducted jointly by two radiologists, a surgeon and a pathologist, and any discordance was resolved by consensus.

Measurements

The clinical features (age, sex and presenting symptoms and signs), laboratory data (serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels), and pathological findings (gallstones, tumor morphology, gallbladder size, histopathological evaluation of T-staging and nodal metastasis) were recorded. With pathology as the gold standard, the true-positive and false-negative results of preoperative US and CT were obtained, and the sensitivity of the imaging modalities was determined. The outcomes of our patients were also documented.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean ± SD or number (%). The clinical, laboratory and pathological findings were analyzed and compared between the intraluminal-GBCA and infiltrating-GBCA group using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test for categorical variables. The sensitivity of preoperative US and CT for the diagnosis of GBCA between the two groups with and without gallstones also was analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed with SYSTAT software (SPSS, version 11.0, Chicago, IL, USA) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical and laboratory information

Eight of 73 patients with a discharge diagnosis of GBCA were excluded from further study. Three of these patients refused surgery; three were considered poor candidates for surgery because of concurrent cardiac or pulmonary disease or old age; and the other two lacked preoperative US or CT images for review. A total of 65 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included. According to the pathological findings, 37 patients (female:male = 23:14; mean age, 65.5 years) formed the intraluminal-GBCA group and the other 28 patients (female:male = 18:10; mean age, 73.1 years) formed the infiltrating-GBCA group.

The clinical and pathological data of both groups are compared in Table 1. Female preponderance was noted in both groups but the patients in the infiltrating-GBCA group were significantly older than those in the intraluminal-GBCA group (P = 0.02). The presenting symptoms were, in combination or alone, right upper abdominal or epigastric pain or discomfort in 51 patients, jaundice in 23 and fever in 13. Ten patients were asymptomatic and were diagnosed incidentally. The infiltrating-GBCA group had a higher frequency of jaundice (46.4% vs 8.1%, P < 0.001) and fever (35.7% vs 8.1%, P = 0.006) than the intraluminal-GBCA group. There were no significant differences in the serum aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels between the groups. However, the infiltrating-GBCA group had significantly higher levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (220.68 IU/L vs 119.36 IU/L, P = 0.03) and total bilirubin (3.50 mg/dL vs 1.74 mg/dL, P = 0.011) than the intraluminal-GBCA group.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological data from 37 patients with GBCA presented as intraluminal mass, and 28 patients with GBCA presented as infiltrating tumor (mean ± SD) n (%)

| Intraluminal mass | Infiltrating tumor | P value | |

| Age (yr)2 | 65.49 ± 1.51 | 73.07 ± 1.90 | 0.020a |

| Sex ratio (female)1 | 23 (62.1) | 18 (64.3) | 0.861 |

| RUQ or epigastric pain or discomfort1 | 28 (75.7) | 23 (82.1) | 0.530 |

| Jaundice1 | 3 (8.1) | 13 (46.4) | < 0.001a |

| Fever1 | 3 (8.1) | 10 (35.7) | 0.006a |

| Incidental finding | 7 (18.9) | 3 (8.1) | 0.364 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L)2 | 89.36 ± 101.14 | 74.37 ± 88.62 | 0.914 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L)2 | 113.21 ± 103.97 | 78.87 ± 82.04 | 0.252 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L)2 | 119.36 ± 87.80 | 220.68 ± 164.84 | 0.030a |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL)2 | 1.74 ± 2.87 | 3.50 ± 3.51 | 0.011a |

| Presence of gallstones1 | 12 (32.4) | 22 (78.6) | < 0.001a |

| Gallbladder size | |||

| Length (cm)2 | 7.47 ± 1.70 | 6.47 ± 1.83 | 0.032a |

| Width (cm)2 | 4.21 ± 1.43 | 2.67 ± 0.93 | 0.026a |

| T1 tumor1 | 8 (21.7) | 1 (3.6) | 0.038a |

| T2 tumor1 | 11(29.7) | 9 (32.1) | 0.835 |

| T3 tumor1 | 17 (45.9) | 16 (57.1) | 0.267 |

| T4 tumor1 | 1 (2.7) | 2 (7.2) | 0.581 |

| Metastatic lymph nodes1 | 13 (35.1) | 15 (53.6) | 0.712 |

| Survival < 12 mo1 | 16 (43) | 18 (68) | 0.017a |

Fisher's exact test or χ2 test;

Wilcoxon rank sum test;

Significant at 0.05; RUQ: Right upper quadrant; GBCA: Gallbladder carcinoma.

Pathological findings

The histological types in the intraluminal-GBCA group included 34 adenocarcinomas, one papillary adenocarcinoma, one sarcomatoid adenocarcinoma and one adenosquamous carcinoma. The maximal tumor length ranged from 1.1 to 3.8 cm (mean 2.3 cm). Among 34 intraluminal adenocarcinomas, five patients had no associated gallstones, while histopathological examinations revealed tumor development from the tubular or villotubular polypoid adenomas. The histological types in the infiltrating-GBCA group included 24 adenocarcinomas, two adenosquamous carcinomas, one clear cell carcinoma and one squamous cell carcinoma. The maximal thickness of the tumor ranged from 0.7 to 1.2 cm (mean 0.9 cm). Thirty-four of these 65 patients had gallstones and the number of stones ranged from one to 35. Twenty-six of these patients had > 3 stones with sizes ranging from 0.5 to 2.9 cm, and the other eight patients had 1-3 stones, with sizes varying from 0.3 to 2.7 cm. The infiltrating-GBCA group exhibited a significantly higher frequency of gallstones than the intraluminal group (78.6% vs 32.4%, P < 0.001). Compared with the intraluminal-GBCA group, the infiltrating-GBCA group exhibited a significantly shorter gallbladder length (7.47 cm vs 6.47 cm, P = 0.032) and width (4.21 cm vs 2.67 cm, P = 0.026), and had a significantly lower frequency of T1 tumors (21.7% vs 3.6%, P = 0.038). On the other hand, there were no significant differences between our two groups with respect to the frequencies of T2, T3, or T4 tumors, and the presence of regional metastatic lymph nodes.

Preoperative US and CT

Comparison of preoperative US and CT diagnosis is summarized in Table 2. Twelve out of 37 (32.4%) patients in the intraluminal mass group had gallstones and 11 of them underwent US, with a sensitivity of 63.6% for preoperative diagnosis of GBCA, while five underwent CT, with a sensitivity of 80%. Twenty-two out of 28 (78.6%) patients in the infiltrating-GBCA group had gallstones and 16 of them underwent US, with a sensitivity of only 12.5% for preoperative diagnosis of GBCA, while 14 underwent CT, with a sensitivity of 71.4%.

Table 2.

Comparison of preoperative US and CT diagnosis of 37 patients with GBCA presented as intraluminal mass, and 28 patients with GBCA presented as infiltrating tumor

| Intraluminal mass | Infiltrating tumor | |

| With gallstones | 12 | 22 |

| Preoperative US | 11 | 16 |

| True positive | 7 | 2 |

| False negative | 4 | 14 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 63.6 | 12.5 |

| Preoperative CT | 5 | 14 |

| True positive | 4 | 10 |

| False negative | 1 | 4 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 80.0 | 71.4 |

| Without gallstones | 25 | 6 |

| Preoperative US | 23 | 4 |

| True positive | 21 | 1 |

| False negative | 2 | 3 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 91.3 | 25.0 |

| Preoperative CT | 20 | 4 |

| True positive | 20 | 3 |

| False negative | 0 | 1 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 100 | 75 |

US: Ultrasound; CT: Computed tomography.

Twenty-five out of 37 (67.64%) patients in the intraluminal mass group had no gallstones and 23 of them underwent US, with a sensitivity of 91.5% for preoperative diagnosis of GBCA, while 20 underwent CT, with a sensitivity of 100%. Only six out of 28 (21.4%) patients in the infiltrating-GBCA group had no gallstones and four of them underwent US, with a sensitivity of only 25% for preoperative diagnosis of GBCA, while four underwent CT, with a sensitivity of 75%.

None of the 22 patients (15 without and seven with gallstones) in the intraluminal-GBCA group with both preoperative US and CT (Figures 1 and 2), had a false-negative result for GBCA. However, among 10 patients (two without and eight with gallstones) in the infiltrating-GBCA group, US and CT results were true-positive for GBCA in only four patients (Figure 3). The US results were false-negative for GBCA in the remaining six patients (five with gallstones), and CT was true-positive in four (Figures 4 and 5).

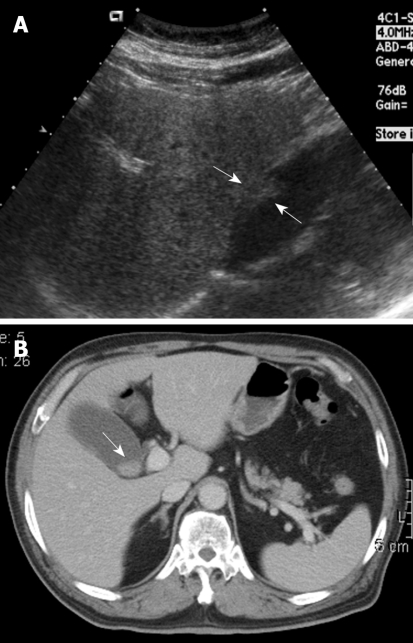

Figure 1.

A 68-year-old woman with intermittent dull right upper quadrant pain for 6 mo. A: Ultrasound (US) showed a sessile polypoid lesion (arrows) with a mildly uneven surface; B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed an intraluminal polypoid lesion (arrow) with no apparent enlarged regional lymph node.

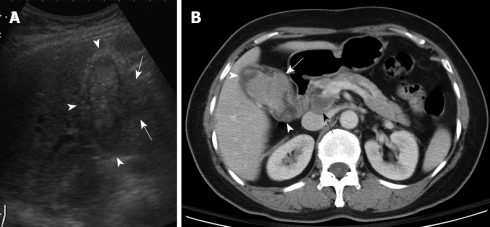

Figure 2.

A 78-year-old woman with right upper abdominal pain and progressive jaundice for 2 mo. A: US showed an intraluminal heteroechoic mass that occupied nearly the whole gallbladder (arrowheads), with focal extraluminal invasion (arrows); B: Contrast-enhanced CT showed a large lobulated mass within the gallbladder (arrowheads), with extracholecystic invasion (white arrow) and hepatoduodenal ligament lymph node metastasis (black arrow).

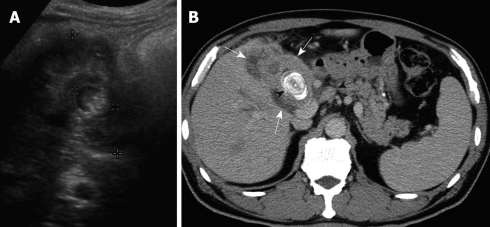

Figure 3.

A 77-year-old woman with right upper abdominal pain and jaundice for 1 mo. A: US showed a large gallstone (× cursors) encased by the diffusedly thickened gallbladder wall, with a heteroechoic appearance (+ cursors); B: Contrast-enhanced CT showed diffuse, uneven wall thickening of the gallbladder (white arrows), with a large laminated gallstone (arrowhead) and hepatoduodenal ligament lymph node metastasis (black arrow).

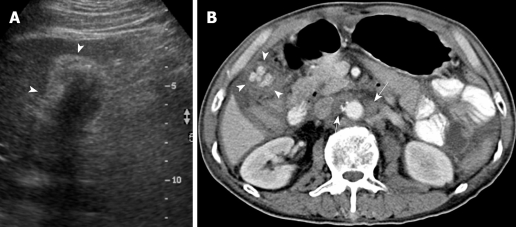

Figure 4.

A 61-year-old man with dull right upper abdominal pain for 3 wk. A: US showed a relatively small gallbladder with focal wall thickening (arrows), which was misinterpreted initially as inadequate gallbladder distension; B: Contrast-enhanced CT was done because of persistent abdominal discomfort. It revealed relatively poor distension of the gallbladder with prominent enhancement of the focally thickened gallbladder wall (white arrows) and celiac lymph node metastasis (black arrow).

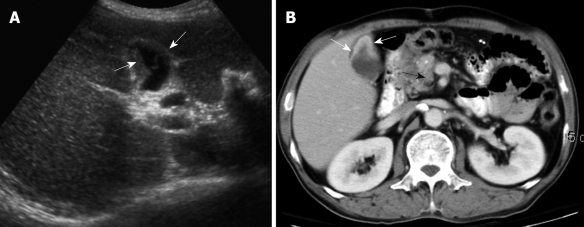

Figure 5.

A 78-year-old man admitted to the emergency room with right upper abdominal pain, fever and jaundice for 1 d. A: US showed a contracted gallbladder with a thickened wall (arrowheads) and multiple gallstones that obliterated underlying details, which mimicked chronic cholecystitis; B: Contrast-enhanced CT showed a relatively small gallbladder with uneven wall thickening (arrowheads), multiple gallstones and pericholecystic inflammatory stranding and fluid suggestive of gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA), with coexistent acute cholecystitis. Note the intercavoaortic and left para-aortic lymph node metastasis (white arrows).

Outcomes

In the intraluminal-GBCA group, T1 tumors were found in eight patients, T2 in 11, T3 in 17, and T4 in one. Follow-up ranged from 3 to 115 mo (average 28.8 mo) and 16 patients (43%) survived < 12 mo (average survival, 9 mo). In the infiltrating-GBCA group, a T1 tumor was found in only one patient, T2 in nine, T3 in 16, and T4 in two. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 160 mo (average 15.5 mo) and 19 patients (68%) survived < 12 mo (average survival, 4 mo). The percentage of patients with < 1-year survival in the infiltrating group was significantly higher than in the intraluminal-GBCA group (P = 0.017).

DISCUSSION

GBCA is a relatively uncommon cancer and is found incidentally in < 1% of 750 000 open cholecystectomies performed annually for gallstones in the United States[12]. Although GBCA is characterized by early local invasion of the liver and biliary tree, early diagnosis remains difficult because most patients present with nonspecific abdominal symptoms[2-5]. In the present study, most patients in both groups harbored T2 and T3 tumors and complained of chronic right upper quadrant or epigastric discomfort at presentation, but our results showed that intraluminal and infiltrating-GBCA might demonstrate different clinical manifestations. In patients with intraluminal-GBCA, T1 tumors were detected more commonly by US or CT incidentally as an asymptomatic gallbladder nodule, while patients with infiltrating GBCA exhibited a higher frequency of jaundice and fever, which mimicked acute cholecystitis. Although both groups showed similar abnormal mean levels of serum aminotransferases, patients with infiltrating-GBCA had significantly higher levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (220.7 IU/L vs 119.4 IU/L) and total bilirubin (3.5 mg/dL vs 1.7 mg/dL) than patients with intraluminal-GBCA.

Epidemiological studies have shown that female sex, age, postmenopausal status, ethnic differences and gallstones are the most well-known factors for GBCA development[9,13-16]. A high prevalence of GBCA has been reported in New Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, Israel and Northern Japan, and a high prevalence of gallstones in these ethnic groups has also been found[14,15]. Chronic irritation of the gallbladder caused by gallstones and tumor-promoter activity in the bile in cholelithiasis patients may account for the development of GBCA[16,17]. In the present study, gallstones were identified in 34/67 patients (54%), with a lower incidence than in previous reports (64%-98%)[18-20]. Of note, our results showed that significantly more patients with infiltrating-GBCA (22/28 patients, 78.6%) harbored coexisting gallstones than patients with intraluminal-GBCA (12/37 patients, 32.6%). Coupled with the fact that patients with infiltrating-GBCA were significantly older (mean age, 73 years) and had significantly smaller gallbladders than those with intraluminal-GBCA, we concur with the postulation that gallstones with a long duration of gallbladder wall irritation may lead to mucosal dysplasia and subsequent neoplasia[19].

In contrast, more than two-thirds of patients with intraluminal-GBCA had no gallstones, and other predisposing factors of GBCA development including polypoid gallbladder lesions, choledochal cyst, pancreatobiliary duct anomalies, sclerosing cholangitis, porcelain gallbladder, cigarette smoking, typhoid carrier state, certain occupational and environmental carcinogens, and hormonal changes in women have also been described[9,13-15]. None of our patients had any history of congenital bile duct or pancreatobiliary lesions, porcelain gallbladder or sclerosing cholangitis, but they did have other less common factors such as chemical or carcinogen exposure. Gallbladder polyps that are > 1 cm, single, sessile, and echogenic have been associated with a higher risk of malignancy, especially in patients > 60 years old[15,21-23]. The present study showed that the maximal diameter of intraluminal-GBCA varied from 1.1 to 3.8 cm (mean 2.3 cm), while the mean age of the patients was 65.5 years. Of note, five of our patients with intraluminal adenocarcinoma had no gallstones, while histopathological examination revealed tumor development from tubular or villotubular polypoid adenomas. Furthermore, all eight T1 tumors in the intraluminal-GBCA group had diameters between 1.1 and 1.4 cm. Therefore, our results supported prophylactic cholecystectomy of a single intraluminal polyp or mass > 1 cm in diameter[15].

Although many physicians express a relatively nihilistic approach to the treatment of GBCA, several studies have encouraged an aggressive surgical approach that might lead to improved survival[3-5]. Early detection and accurate preoperative diagnosis of GBCA is highly beneficial for surgical planning, especially in avoidance of laparoscopic surgery, which may induce recurrent tumors in the abdominal wall along the port track[24,25]. Abdominal US and CT are the most common modalities for assessing suspected hepatobiliary malignancies[6-11]. US allows the correct diagnosis in 70%-80% of advanced and 20%-30% of early gallbladder carcinoma cases[6-9]. The present study disclosed that US was fairly sensitive for detecting intraluminal-GBCA with gallstones (sensitivity 63.6%) and highly sensitive for intraluminal-GBCA without gallstones (sensitivity 91.3%). Intraluminal-GBCA may appear as a hypoechoic polypoid lesion (> 1 cm) that projects into the lumen, a fungating mass, or a large mass that replaces the gallbladder, on US[6-9]. In contrast, benign cholesterol or inflammatory polyps are usually multiple, hyperechoic and < 1 cm in diameter[6,21-23]. Intraluminal-GBCA with a fungate appearance or large mass can be distinguished by a heterogeneous echotexture and irregular border of the lesions, as well as intralesional or perilesional echogenic foci and acoustic shadowing caused by coexisting gallstones and tumoral calcification[7-9]. On the contrary, US has poor sensitivity for detecting infiltrating-GBCA, with and without gallstones (sensitivity of 12.5% and 25.0%, respectively). As demonstrated in the present study, possibly as a result of chronic gallbladder wall irritation by gallstones, and the infiltrating nature of the tumor, which might limit gallbladder expansion, the mean gallbladder size was significantly smaller in patients with infiltrating-GBCA than in those with intraluminal-GBCA. Subtle gallbladder wall thickening that leads to misinterpretation as chronic inflammatory changes, coexistence of acute cholecystitis and obliteration by concurrent gallstones or bile sludge are also factors that might hamper the US detection of infiltrating-GBCA[6].

Similar to US, GBCA may appear as an intraluminal or infiltrating tumor upon CT[7-9]. Our study showed that CT was 80% and 100% sensitive, respectively, for detecting intraluminal-GBCA with and without gallstones. In contrast to US, CT offered 71.4% and 75% sensitivity, respectively, for detecting infiltrating-GBCA with and without gallstones. Focal or diffuse gallbladder wall thickening (maximal thickness from 0.7 to 1.2 cm, mean 0.9 cm) is the most common CT finding. This finding is nonspecific and may occur in a variety of conditions, including extracholecystic inflammatory processes such as hepatitis, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, adenomyomatosis, and chronic or xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis[24-27]. However, CT allows assessment of the condition of the liver, pancreas and kidney, and thus exclusion of secondary involvement of the gallbladder in extracholecystic inflammation is not difficult[24,25]. CT also is helpful for revealing adenomyomatosis with proliferation of the subserosal fat and intramural diverticula with small calculi, chronic cholecystitis with a double-layered small gallbladder and a weakly enhancing thin inner layer, and xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis with intramural hypoattenuated nodules in a thickened gallbladder wall[24-27].

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature. First, all patients had surgically proven GBCA, and thus, it was not possible to establish a false-positive rate for US and CT. A prospective study is needed to validate the accuracy, specificity, and true- and false-predictive values of US and CT for intraluminal and infiltrating-GBCA, but due to the infrequency of GBCA, such a large-scale prospective study may be difficult. Second, only a small proportion of our patients underwent percutaneous cholangiography, radionuclide and magnetic resonance imaging studies and hence, the role of these studies in these two morphologically different types of GBCA could not be determined.

In summary, in contrast to intraluminal-GBCA, infiltrating-GBCA is overlooked easily on US. In elderly women with suspected small gallbladder and gallstones upon US, especially those with jaundice, fever, and high serum alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels, CT is helpful in surveying underlying infiltrating-GBCA.

COMMENTS

Background

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBCA) is a relatively uncommon cancer with early local invasion of the liver and biliary tree, but early diagnosis remains difficult because most patients present with nonspecific abdominal symptoms. Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) have been reported as helpful tools for imaging and staging of GBCA. To the best of our knowledge, the influences of different tumor morphology on clinical presentation, as well as on US and CT sensitivity of GBCA detection have not been well studied.

Research frontiers

US is the main initial diagnostic tool for suspected biliary lesions and may be helpful for detecting GBCA. GBCA may present as an intraluminal mass and an infiltrating tumor, and the infiltrative morphology of some tumors may render US assessment difficult. In addition, the presence of gallstones, inflammation and debris may preclude tumor detection by US. CT has been reported as a comprehensive tool for imaging and staging of GBCA, but its usefulness in patients with different tumor morphology has not been explored.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results demonstrated that, compared with patients with intraluminal-GBCA, patients with infiltrating-GBCA were significantly older, and had a significantly higher frequency of jaundice and fever, higher alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels, higher frequency of gallstones, smaller gallbladder size and shorter survival. The sensitivity for diagnosing intraluminal-GBCA with and without gallstones was 63.6% and 91.3%, respectively, by US, and 80% and 100%, respectively, by CT. The sensitivity for diagnosing infiltrating-GBCA with and without gallstones was 12.5% and 25%, respectively, by US, and 71.4% and 75%, respectively, by CT.

Applications

Intraluminal and infiltrating-GBCA exhibit different clinical presentations and features by US and CT. US and CT are fairly to highly sensitive for detecting intraluminal-GBCA with and without gallstones. Conversely, infiltrating-GBCA, especially when associated with gallstones, is overlooked easily by US. Further CT examination can be useful in revealing underlying infiltrating-GBCA in elderly women with relatively small gallbladders and gallstones noted by US, particularly those with jaundice, fever, and high serum alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels.

Terminology

Intraluminal-GBCA denotes tumor growths that protrude into the gallbladder lumen, which appear grossly as polypoid, fungating or large intraluminal masses. Infiltrating-GBCA denotes infiltrating carcinomas that appear grossly as focal or diffuse areas of wall thickening, or induration of the gallbladder wall.

Peer review

This is an interesting report of gallbladder cancer with differences in clinical presentation. Although it is of clinical significance, the presentation of the paper needs some modification.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Toru Ishikawa, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, Saiseikai Niigata Second Hospital, Teraji 280-7, Niigata, Niigata 950-1104, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fong Y, Malhotra S. Gallbladder cancer: recent advances and current guidelines for surgical therapy. Adv Surg. 2001;35:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557–569. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon E, Vollmer CM Jr, Sahajpal A, Cattral M, Grant D, Doig C, Hemming A, Taylor B, Langer B, Greig P, et al. An aggressive surgical approach leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer: a 12-year study at a North American Center. Ann Surg. 2005;241:385–394. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154118.07704.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogura Y, Mizumoto R, Isaji S, Kusuda T, Matsuda S, Tabata M. Radical operations for carcinoma of the gallbladder: present status in Japan. World J Surg. 1991;15:337–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01658725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchiya Y. Early carcinoma of the gallbladder: macroscopic features and US findings. Radiology. 1991;179:171–175. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.1.2006272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gore RM, Yaghmai V, Newmark GM, Berlin JW, Miller FH. Imaging benign and malignant disease of the gallbladder. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1307–1023, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooholamini SA, Tehrani NS, Razavi MK, Au AH, Hansen GC, Ostrzega N, Verma RC. Imaging of gallbladder carcinoma. Radiographics. 1994;14:291–306. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.14.2.8190955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy AD, Murakata LA, Rohrmann CA Jr. Gallbladder carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21:295–314; questionnaire, 549-555. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr16295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalra N, Suri S, Gupta R, Natarajan SK, Khandelwal N, Wig JD, Joshi K. MDCT in the staging of gallbladder carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:758–762. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SJ, Lee JM, Lee JY, Kim SH, Han JK, Choi BI, Choi JY. Analysis of enhancement pattern of flat gallbladder wall thickening on MDCT to differentiate gallbladder cancer from cholecystitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:765–771. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih SP, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Choti MA, Campbell KA, Yeo CJ, Talamini MA. Gallbladder cancer: the role of laparoscopy and radical resection. Ann Surg. 2007;245:893–901. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31806beec2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan ZR, Neugut AI, Ahsan H, Chabot JA. Risk factors for biliary tract cancers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strom BL, Soloway RD, Rios-Dalenz JL, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, West SL, Kinman JL, Polansky M, Berlin JA. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer. An international collaborative case-control study. Cancer. 1995;76:1747–1756. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10<1747::aid-cncr2820761011>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheth S, Bedford A, Chopra S. Primary gallbladder cancer: recognition of risk factors and the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1402–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta SC, Misra V, Singh PA, Roy A, Misra SP, Gupta AK. Gall stones and carcinoma gall bladder. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2000;43:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Z, Wang Z, Zhang J. [Carcinogenicity of bile from cholecystolithiasis patients] Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2001;81:268–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diehl AK. Gallstone size and the risk of gallbladder cancer. JAMA. 1983;250:2323–2326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csendes A, Becerra M, Rojas J, Medina E. Number and size of stones in patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones and gallbladder carcinoma: a prospective study of 592 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:481–485. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagorney DM, McPherson GA. Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. Semin Oncol. 1988;15:106–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Polypoid lesion of the gallbladder: indications of carcinoma and outcome after surgery for malignant polypoid lesion. Int Surg. 1994;79:106–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang HL, Sun YG, Wang Z. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: diagnosis and indications for surgery. Br J Surg. 1992;79:227–229. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shinkai H, Kimura W, Muto T. Surgical indications for small polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 1998;175:114–117. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zissin R, Osadchy A, Shapiro-Feinberg M, Gayer G. CT of a thickened-wall gall bladder. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:137–143. doi: 10.1259/bjr/63382740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Breda Vriesman AC, Engelbrecht MR, Smithuis RH, Puylaert JB. Diffuse gallbladder wall thickening: differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:495–501. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yun EJ, Cho SG, Park S, Park SW, Kim WH, Kim HJ, Suh CH. Gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis: differentiation with two-phase spiral CT. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:102–108. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chun KA, Ha HK, Yu ES, Shinn KS, Kim KW, Lee DH, Kang SW, Auh YH. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: CT features with emphasis on differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma. Radiology. 1997;203:93–97. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]