Abstract

Problem

India has the world’s largest number of maternal deaths estimated at 117 000 per year. Past efforts to provide skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care in rural areas have not succeeded because obstetricians are not willing to be posted in government hospitals at subdistrict level.

Approach

We have documented an innovative public–private partnership scheme between the Government of Gujarat, in India, and private obstetricians practising in rural areas to provide delivery care to poor women.

Local setting

In April 2007, the majority of poor women delivered their babies at home without skilled care.

Relevant changes

More than 800 obstetricians joined the scheme and more than 176 000 poor women delivered in private facilities. We estimate that the coverage of deliveries among poor women under the scheme increased from 27% to 53% between April and October 2007. The programme is considered very successful and shows that these types of social health insurance programmes can be managed by the state health department without help from any insurance company or international donor.

Lessons learned

At least in some areas of India, it is possible to develop large-scale partnerships with the private sector to provide skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care to poor women at a relatively small cost. Poor women will take up the benefit of skilled delivery care rapidly, if they do not have to pay for it.

Résumé

Problématique

L'Inde est le pays du monde subissant la plus forte mortalité maternelle, estimée à 117 000 décès par an. Les efforts consentis dans le passé pour fournir une assistance à la naissance par du personnel qualifié et des soins obstétricaux d'urgence dans les zones rurales n'ont pas abouti car les obstétriciens étaient peu disposés à être affectés dans des hôpitaux publics de niveau inférieur au district.

Démarche

Nous avons réuni des informations sur un partenariat public/privé innovant entre le Gouvernement du Gujarat en Inde et des obstétriciens privés exerçant dans des zones rurales, ayant pour objectif de proposer des soins à l'accouchement aux femmes pauvres.

Contexte local

En avril 2007, la majorité des femmes pauvres accouchaient à domicile, sans recevoir de soins qualifiés.

Modifications pertinentes

Plus de 800 obstétriciens ont accepté de participer au schéma et plus de 176 000 femmes pauvres ont accouché dans des établissements privés. Nous estimons que la couverture par l'assistance à l'accouchement dans le cadre du schéma chez les femmes pauvres est passée de 27 % à 53 % entre avril et octobre 2007. Ce programme est considéré comme très fructueux et montre que les programmes sociaux d'assurance santé de ce type peuvent être gérés par le Ministère de la santé, sans l'aide d'une compagnie d'assurance ou d'un donateur international.

Enseignements tirés

Dans certaines zones de l'Inde au moins, il est possible de développer des partenariats à grande échelle avec le secteur privé pour offrir une assistance à la naissance par du personnel qualifié et des soins obstétricaux d'urgence aux femmes pauvres, à un coût relativement faible. Les femmes pauvres seront rapidement demandeuses de soins à l'accouchement qualifiés si elles n'ont pas à les payer.

Resumen

Problema

La India es el país con mayor número de defunciones maternas, estimadas en 117 000 al año. Los esfuerzos desplegados hasta ahora para dotar de parteras cualificadas y atención obstétrica de urgencia a las zonas rurales no han tenido éxito porque los obstetras no están dispuestos a trabajar en hospitales públicos a nivel subdistrital.

Enfoque

Hemos documentado una innovadora fórmula de colaboración publicoprivada acordada entre el gobierno de Gujarat, India, y obstetras privados que ejercen en zonas rurales para proporcionar atención obstétrica a las mujeres pobres.

Contexto local

En abril de 2007, la mayoría de las mujeres pobres dieron a luz en el hogar sin atención cualificada.

Cambios destacables

Más de 800 obstetras participaron en ese sistema, y más de 176 000 mujeres pobres dieron a luz en centros privados. Estimamos que la cobertura de partos asistidos entre las mujeres pobres en el marco de ese sistema aumentó del 27% al 53% entre abril y octubre de 2007. El programa, que se considera que ha tenido gran éxito, muestra que este tipo de iniciativas de seguro social de enfermedad pueden ser administradas por el ministerio de salud sin ayuda de ningún donante internacional o aseguradora.

Enseñanzas extraídas

Al menos en algunas zonas de la India, es posible forjar alianzas en gran escala con el sector privado al objeto de proporcionar parteras cualificadas y atención obstétrica de urgencia para las mujeres pobres a un costo relativamente bajo. Si saben que pueden obtenerla gratuitamente, las mujeres pobres no tardan en recurrir a la atención obstétrica de urgencia.

ملخص

المشكلة

تعاني الهند من أكبر عدد من وفيات الأمهات التي تقدر بـ 117 ألف وفاة سنوياً. ولم تنجح الجهود التي بذلت سابقاً لتوفير الرعاية الماهرة للولادة والرعاية التوليدية الطارئة في المناطق الريفية بسبب عدم رغبة أطباء التوليد في التعيين في المستشفيات الحكومية في المناطق الريفية والنائية.

الطريقة

وثّق الباحثون خطة مبتكرة للشراكة بين القطاعين العام والخاص، وذلك بين الحكومة في غوجارات في الهند وأطباء التوليد الذين يعملون في القطاع الخاص في المناطق الريفية لتقديم الرعاية التوليدية للفقيرات.

الوضع المحلي

في نيسان/إبريل 2007، ولدت معظم الفقيرات أطفالهن في المنزل بدون توفّر رعاية ماهرة للولادة.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

التحق أكثر من 800 طبيب توليد في الخطة، ووضعت أكثر من 176 ألف امرأة فقيرة مواليدهن في مرافق القطاع الخاص. وقدّر الباحثون أن تغطية ولادات الفقيرات اللاتي أدرجن في الخطة قد ازدادت من 27% في نيسان/إبريل 2007 إلى 53% في تشرين الأول/أكتوبر 2007. وقد اُعتُبِر البرنامج برنامجاً ناجحاً جداً، وأثبت أن هناك ثلاثة أنماط من برامج الضمان الصحي يمكن إدارتها من قِبَل الإدارة الصحية للدولة دون مساعدة من أية شركة للضمان الصحي أو من أي وكالة دولية مانحة.

الدروس المستفادة

يمكن، على أقل تقدير في بعض مناطق الهند، تطوير شراكات واسعة النطاق مع القطاع الخاص لتقديم رعاية توليدية طارئة للفقيرات وبتكاليف قليلة نسبياً. وستستفيد الفقيرات من الرعاية التوليدية الماهرة بسرعة إذا لم يتوجب عليهن دفع تكاليفها.

Introduction

India has the largest number of births (27 million), maternal deaths (estimated at about 117 000) and neonatal deaths (1 098 000) per year in the world.1,2 There are several reasons for the high maternal mortality rate in India including non-availability of obstetricians and skilled birth attendants in rural areas.3–6

Problem and local setting

One of the key constraints in providing comprehensive emergency obstetric care services to rural people in India is non-availability of obstetricians in the government hospitals.7,8 India (with a population of 1.1 billion) has about 22 000 obstetricians,9 but less than 13007 work in government hospitals in rural areas mainly due to inadequate infrastructure and low fixed salaries.

Gujarat state (with a population of 55 million), on the west coast of India, has 17 738 registered doctors (with about 2000 obstetricians) three quarters of whom work in private health facilities.10 Those working in government facilities are largely in urban areas. In Gujarat, the availability of government obstetricians at subdistrict level is appalling, with only 7–8 government obstetricians serving a total rural population of 32 million.7 One of the probable reasons for this situation is that government policy does not allow government doctors to do private practice. Gujarat has a fairly good number of private obstetricians practising in rural areas.

Approach

In October 2005, the Gujarat government in consultation with the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, the Society for Education, Welfare and Action – Rural (SEWA Rural) in Jhagadia and the German development organization (GTZ) developed a pilot programme in five districts (with a population of 11 million) to provide skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care. It was a pioneering public–private partnership called Chiranjeevi Yojana – a local name meaning “a scheme for long life (of mothers and babies)”. The government selected private obstetricians using simple criteria and contracted them to provide delivery care to poor women in rural areas.

Payment mechanism

Under this scheme, the private obstetricians provided skilled birth attendance and comprehensive emergency obstetric care free of charge to poor women. In return, the government paid the obstetricians US$ 4600 for a package of 100 deliveries including treatment of complications, an average price of US$ 46 per delivery. This is not a very high price considering India’s per capita income (purchasing power parity adjusted) is about US$ 3000.11 The monetary reimbursements were worked out based on costs in a private setting in rural areas by SEWA Rural, a reputable nongovernmental organization.

Even though higher amounts were notionally allocated for treatment of complications – for example 5000 Indian rupees (Rs) or US$ 125 for caesarean section versus Rs 800 or US$ 20 for normal delivery – the key distinguishing feature of the payment package was that it assumed a fixed rate of caesareans (7%) and other complications based on the international epidemiological estimates and local experience. This financial arrangement removed the monetary incentive for doing more caesarean sections – a common problem in fee-for-service private practice in India.12 In addition, out of the US$ 46 they received per delivery, the obstetricians had to pay the women giving birth US$ 5 for transportation to reduce the delay in reaching the hospital. The obstetricians also had to pay US$ 1 to the person who accompanied the woman, in a plan to reduce the tendency of traditional birth attendants to avoid referring women to health facilities.

The scheme is only for poor women. In India, poor people are defined as “below the poverty line” using criteria set for several other social welfare programmes and are issued with a card by the government. This card entitled them to free delivery facilities under the Chiranjeevi scheme in a private hospital.

Enrolment of private doctors

The scheme was promoted via meetings with the community leaders, local obstetric and gynaecological society and district health teams. Auxiliary nurse midwives and other peripheral health functionaries played a key role in promoting institutional deliveries under this scheme. It was managed by the district and block health officers. No incentive was paid to government workers to promote the scheme, nor was any insurance company interested due to the low prices.13

The health commissioner and directors convinced rural obstetricians to join the scheme using personal visits and meetings in the districts. The selection criteria for the enrolment of a private obstetrician were post-graduate qualifications in obstetrics and access to a small maternity facility where caesarean sections could be performed. To allay the fears that the government would not pay dues on time, doctors were given advance payments of about US$ 625 on signing the contract. As deliveries occurred, the obstetricians were reimbursed rapidly by the district health office. Paper work was kept to a minimum.14 Based on the success of the first year of the scheme, it was extended in January 2007 to the entire poor population of the state, approximately 12.65 million people.

Performance, scale-up and sustainability

In the five pilot districts, 180 obstetricians joined the scheme in the first year. From January 2006 to March 2008, around 97 192 poor women delivered in private hospitals under the scheme. Each obstetrician did an average of 540 deliveries and earned US$ 24 840 from the scheme. Thus the scheme turned out to be a win-win situation for the poor women, the private doctors and the district health authorities. After scaling up the scheme to the whole state, 865 of around 2000 private practising obstetricians joined. A total of 176 293 deliveries were conducted under the scheme by March 2008.

Even though the deliveries increased rapidly in the private facilities, the caesarean section rate was under control at about 6.23%. This is much higher than the 2–3% rate seen in poor quintiles of the population in India, suggesting that the scheme has increased their access to caesarean section. Table 1 gives the details of deliveries in each district, complications treated and caesareans done under this scheme. There is substantial variation in the caesarean rate between districts, possibly due to a difference in need, referral patterns and lack of standard protocols in private practice.

Table 1. Number of deliveries, caesarean section, complications and obstetricians contracted in Chiranjeevi Scheme in Gujarat, April 2007 to March 2008.

| District | Normal delivery | Caesarean delivery | Complicated delivery | Total delivery | Caesarean (%) | Doctors enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gandhinagar | 1 648 | 273 | 152 | 2 073 | 13.17 | 22 |

| Mehsana | 9 232 | 796 | 638 | 10 666 | 7.46 | 40 |

| Patan | 9 815 | 912 | 256 | 10 983 | 8.30 | 35 |

| Ahmedabad | 17 704 | 743 | 0 | 18 447 | 4.03 | 202 |

| Kheda | 2 999 | 437 | 100 | 3 536 | 12.36 | 31 |

| Anand | 3 999 | 772 | 17 | 4 788 | 16.12 | 35 |

| Surendranagar | 5 830 | 354 | 72 | 6 256 | 5.66 | 27 |

| Vadodara | 4 371 | 169 | 355 | 4 895 | 3.45 | 51 |

| Bharuch | 1 559 | 226 | 148 | 1 933 | 11.69 | 22 |

| Narmada | 645 | 41 | 48 | 734 | 5.59 | 6 |

| Surat | 1 630 | 100 | 55 | 1 785 | 5.60 | 60 |

| Navsari | 2 017 | 313 | 90 | 2 420 | 12.93 | 18 |

| Valsad | 1 940 | 214 | 62 | 2 216 | 9.66 | 19 |

| Ahwa-Dang | 172 | 36 | 5 | 213 | 16.90 | 4 |

| Rajkot | 2 832 | 139 | 66 | 3 037 | 4.58 | 45 |

| Jamnagar | 954 | 28 | 6 | 988 | 2.83 | 21 |

| Bhavnagar | 1 659 | 197 | 38 | 1 894 | 10.40 | 11 |

| Amreli | 323 | 30 | 8 | 361 | 8.31 | 12 |

| Junagadh | 854 | 146 | 35 | 1 035 | 14.11 | 15 |

| Porbandar | 644 | 182 | 15 | 841 | 21.64 | 9 |

| Total for 20 districts | 70 827 | 6 108 | 2 166 | 79 101 | 7.72 | 685 |

| Total for 5 pilot districts | 82 800 | 4 868 | 9 524 | 97 192 | 5.01 | 180 |

| Total for all 25 districts | 153 627 | 10 976 | 11 690 | 176 293 | 6.23 | 865 |

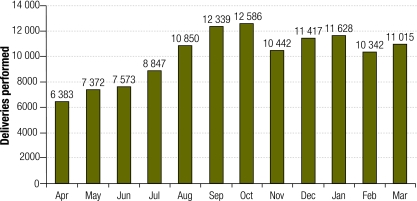

In the whole state, there are a total of about 282 000 deliveries to poor women per year, about 23 500 deliveries per month. The coverage of deliveries done under this scheme among the poor in the state averaged 53% despite some reduction between October 2007 and March 2008 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Number of deliveries per month under Chiranjeevi scheme, Gujarat, April 2007 to March 2008

Currently the scheme is focusing on delivery within private institutions. There is no system yet that monitors quality parameters such as duration of stay after delivery, referral to higher levels of care, who actually conducts the delivery (obstetrician, nurse-midwife under the supervision of obstetrician) and maternal and perinatal mortality following the scheme. The state government is currently working to address some of these issues.

If this scheme is fully used by all poor women in the state, it will cost about Rs 500 million (US$ 10 million), approximately 3% of the state health budget. The scheme is funded by money from the state government budget. Given the high utility of the scheme, the state government is likely to sustain it without any external assistance. The scheme can be replicated by other state governments, but will require substantial facilitation and commitment of the top management. Money alone is not enough to replicate the scheme.

Lessons learned

This scheme provides the first practical experience of involving private obstetricians on a large scale to deliver skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care to poor women in one large state in India. It shows that it is possible to contract with the private sector, to rapidly increase availability and utilization of skilled birth attendants for the poor if governments will pay a reasonable price to private sector obstetricians. The parameters of success in this scheme are: enrolment of a large number of obstetricians at a relatively small delivery cost, increasing usage of institutional delivery by the poor and access to treatment of complications and caesareans in remote areas (Box 1).

Box 1. Lessons learned.

Factors for success were:

Large numbers of obstetricians enrolled at a relatively small delivery cost

Increased institutional delivery for poor women

Access to treatment of complications and caesareans in remote areas.

It provides a new direction to maternal health programming in developing countries where private sector resources are available. This experience also shows that such social health insurance arrangements can be developed relatively rapidly and scaled up by existing health departments without much support from insurance companies or international donors. Such efforts require dynamic leadership from top managers and committed team work of peripheral health staff including nurses, health visitors, medical officers as well as private obstetricians. In countries where private obstetricians are not available in rural areas, similar public-private partnership contracts could be made with private general practitioners and/or midwives or nurses with referrals to obstetricians in cities.

It may be possible to develop a model where government obstetricians in rural areas are paid additional incentive money for providing emergency obstetric care above a certain minimum volume of work, although such additional payment to government doctors is administratively not acceptable in many bureaucracies including India.

There is a strong indication that maternal and neonatal mortality rates have declined due to this intervention and we are in the process of assessing this reduction.15

We are not suggesting that such public-private partnerships should be seen as the panacea for providing care to poor women but they are a workable solution in settings like Gujarat state. Governments and international donors should study such schemes and encourage public-private partnership as one of the strategies to achieve the United Nations Millennium Development Goals through new mechanisms of delivering services to the poor. More research is needed to identify the parameters of successful scaling of such schemes. Future research should include measuring mortality impact, satisfaction of clients, reasons for non-participation of some segments and the willingness of providers to continue and to expand their involvement. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007;370:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn JE, Cousens S. Zupan J for the Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mavalankar DV. Human resource management: issues and challenges. In: Pachauri S, ed. Implementing reproductive health agenda in India: the beginning New Delhi: Population Council;1999. pp. 183-205. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mavalankar DV, Rosenfield A. Maternal mortality in resource-poor settings: policy barriers to care. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:200–3. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.036715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George A. Persistence of high maternal mortality in Koppal district, Karnataka, India: observed service delivery constraints. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:91–102. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavalankar D, Vohra K, Prakasamma M. Achieving Millennium Development Goal 5: is India serious? Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:243. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.048454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Government of India. Rural health statistics bulletin 2006 New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare;2006. Available from: http://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/hia2005/content.asp [accessed on 8 October 2009].

- 8.Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, Mavalankar D, Mridha MK, Anwar I, et al. Going to scale with professional skilled care. Lancet. 2006;368:1377–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India [Internet site]. Number of FOGSI members on 30 June 2008. Available from: http://www.fogsi.org/about_us.html [accessed on 8 October 2009].

- 10.Ramesh B, Verma BB, Elan R. Hospital efficiency: analysis of district and grant-in-aid hospitals in Gujarat. J Health Manag. 2001;4:167–97. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Development Indicators database Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2009. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf [accessed on 7 October 2009].

- 12.Mishra US, Ramanathan M. Delivery complications and determinants of Cesarean section rate in India – and analysis of national family health survey, 1992-93 (Working paper no. 314.) Trivandrum: Center for Development Studies; 2001.

- 13.Ramesh B, Singh A, Maheshwari S, Saha S. Maternal health financing – issues and options: a study of Chiranjeevi Yojana in Gujarat (Working paper 2006-08-03). Ahmedabad: Indian Institute of Management; 2006.

- 14.Singh A. Public private partnership: a solution to maternal mortality. J Fam Welf. 2006;52(supp):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavalankar D, Singh A, Patel SR, Desai A, Singh PV. Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: Chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]