Abstract

Infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL), also known as Santavuori-Haltia disease, is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the lysosomal enzyme palmitoyl-protein-thioesterase-1 (PPT1). Fatty acid-modified proteins are not degraded and accumulate as granular osmiophilic deposits in cells in the CNS; patients have blindness, seizures, progressive psychomotor deterioration and die in early childhood. Although the disease manifests clinically primarily with neurological symptoms, visceral storage also accumulates. A murine model of INCL, due to PPT1 deficiency, exhibits clinical findings and pathology similar to that seen in patients with INCL. Homozygous PPT1 deficient mice have a shortened life span and neurological abnormalities including seizures, blindness and mental and motor deficits. Widespread granular osmiophilic deposits (GROD) accumulate in lysosomes in neurons and glia in the brain, retinal cells, kidney glomerular cells, aortic smooth muscle cells, and, in lesser amounts, in the fixed-tissue macrophage system. Accumulation of GROD in aortic smooth muscle cells is accompanied by abnormalities in cardiac function and aortic root dilatation. This PPT1 deficient murine model is a well-defined genetic system that can be used to test potential therapies for lysosomal storage disease (LSD) and to study the pathophysiology of INCL.

Keywords: Infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, lysosomal storage disease, palmitoyl protein thioesterase

Introduction

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) are a heterogeneous group of more than 40 genetic disorders. Most are due to the deficiency of a lysosomal hydrolase important for lysosomal degradation of macromolecules such as sphingolipids, glycosaminoglycans, glycogen or glycoproteins. The pathology in patients with LSD depends on the nature of the accumulated undegraded substrate and the tissues in which the accumulated material is stored. Many LSDs affect the central nervous system; cells in the fixed-tissue macrophage system are also often the site of storage.

The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL), previously called Batten disease, are a heterogeneous group of at least eight inherited LSDs that are, together, the most common cause of progressive encephalopathy in childhood with a world-wide incidence of approximately 1:10,000 births and a carrier frequency of 1% (1;2). Common to NCL patients are progressive neurodegenerative disease and accumulation of autofluorescent ceroid lipopigments in lysosomes in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues (3). Infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL), also referred to as Santavuori-Haltia disease, is the most rapidly progressive form of NCL and is caused by mutations in the CLN1 gene that encodes for the lysosomal enzyme palmitoyl-protein thioesterase-1 (PPT1) (4). PPT1 cleaves fatty acyl chains from cysteine residues in proteins and is trafficked into lysosomes via the mannose 6-phosphate receptor (5;6). It is one of the most abundant lysosomal enzymes in the brain (7). Patients deficient in this enzyme inherit INCL as an autosomal recessive and have rapid disease progression beginning at around 1.5 years of age with blindness, motor and mental decline, seizures, and lysosomal accumulation of granular osmiophilic deposits (GROD) apparent by electron microscopy in many cell types including neurons. The GROD consists of saposins A and D and morphologically appear as lipopigment (2). Brain atrophy with cortical and CA2 hippocampal neuronal storage and loss with associated astrogliosis occur (2;8). Death in childhood is due to neurodegenerative disease. Although autofluorescent lipopigment accumulates in many tissues, few studies of patients with INCL have described functionally significant manifestations of disease outside of the CNS (9). One explanation for this lack of visceral symptoms is that patients succumb to neurological disease before visceral manifestations are apparent. Therapy for patients with INCL is limited; hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is not recommended (10) but brain-directed gene therapy (5) and drug therapy directed at disruption of thioester linkages (11;12) have been proposed.

A murine knockout model of INCL in mice homozygous for a mutation in the gene that encodes the lysosomal enzyme PPT1 (13) has many clinical features similar to those seen in patients with INCL. Affected mice have neurological abnormalities by 8 months of age and usually die by 10 months of age. Myoclonic seizures, progressive spastic motor abnormalities (13) and retinal dysfunction (5), are accompanied by progressive accumulation of GRODs in lysosomes in brain, microglial activation, loss of GABAergic neurons, apoptosis, widespread astrocytosis and cortical atrophy (14;15). PPT1 mice have secondary elevation of other lysosomal enzymes, a biochemical feature common to many LSDs (5) possibly mediated at both transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (16). This model has been used to test the efficacy of CNS-directed viral-mediated gene therapy using recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) encoding the human PPT1 cDNA (5;17).

Ultrastructural analysis of lysosomal storage accumulation over time in CNS and other tissues of PPT1 knockout mice reported here extends previous observations of the clinical, radiological and morphological abnormalities in these mice. Alterations in cardiac morphology and function identified by ultrasound are also described.

Methods

PPT1 deficient mice were bred on a congenic C57BL/6 background (18). Homozygous PPT1 null mice (ppt/ppt, PPT −/−) were generated through mutant-to-mutant mating; wild type control animals from the same colony (+/+) were also evaluated. A three-primer PCR assay was used to determine the genotype of the wild type and PPT 1 mice (13). All mice were maintained by MSS at Washington University (St. Louis, MO) and all animal procedures were carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations of Washington University.

Morphological analysis was performed on tissues from mice at 1, 3, 5, and 7 months of age. Three PPT1 −/− mice and three wild-type control mice from each group were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Immediately following excision, tissue samples were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide and embedded in Spurr’s resin. The parietal neocortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, liver, spleen, heart, aorta, kidney, retina and bone and marrow from the rib were evaluated by light and electron microscopy for presence of storage material. Toluidine blue-stained 0.5 μ thick sections were examined by light microscopy. For ultrastructural study, ultra-thin sections stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate were viewed in a 100CX JEOL transmission electron microscope.

Cardiac ultrasound was performed on PPT1 −/− mice and age matched controls from 6 to 7.5 months of age. Non-invasive ultrasound examination of the cardiovascular system was performed using a Vevo770 Ultrasound System (VisualSonics Inc, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Mice were anesthetized with continuous inhalation of 1% gaseous isoflurane administered through a customized nose cone. The animals were secured on an imaging platform in supine position; physiologic parameters including heart rate, respiratory rate, and core body temperature were continuously monitored by built-in monitoring system. The anterior chest was shaved and ultrasonic coupling gel was applied. Ultrasound studies were performed using multiple transducers with different ultrasound frequencies (30-60 MHz) depending on the size and depth of the cardiovascular structure of interest. Care was taken to maintain adequate contact while avoiding excessive pressure on the chest. Complete two-dimensional, M-mode, and Doppler ultrasound examination was performed from multiple views.

Results

Clinical description

Prior to 7 months of age, the PPT1 −/− mice were phenotypically indistinguishable from normal littermates and bred normally. By 7 months of age PPT1 −/− mice had significant motor abnormalities in both the constant speed and accelerating rotarod assay (17). At 5 and 7 months, there was decreased retinal function and subtle decrease in the number of photoreceptors (18). At 7 months, PPT 1 −/− mice developed progressive hunched posture with weight loss, scruffy fur and decreased activity. By 8 months the affected mice had myoclonic seizures, the frequency of which increased with age. At 6, 6.5, 7 and 7.5 months of age, electroencephalography indicated that 0, 0, 50 and 100% of the animals, respectively, had seizures (15). There was a significant change in interictal score at 7 and 7.5 months (15;17) , unpublished data).

Pathology

At necropsy, none of the mice had enlarged spleens or pancreases as has been described in another PPT deficient mouse model (19), and there were no gross abnormalities seen. The PPT1 −/− mice accumulated membrane-bound GROD in multiple sites including brain, eye, liver, spleen, heart, aorta, peripheral nerve and kidney (Table 1). The ultrastructure of the storage was similar in all sites and resembled that seen in another murine model of INCL (20) as well as in infants with this disorder. Within all tissues examined, storage was progressive from 3 to 7 months of age (Table 1).

Table 1.

Progressive accumulation of lysosomal storage in PPT −/− mice

| Cell Type | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 3 month | 5 month | 7 month | |

| Kidney | ||||

| Visceral epithelial cells | NS | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ |

| Parietal epithelial cells | NS | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ |

| Mesangial cells | NS | NS | 1+ | 2+ |

| Liver | ||||

| Hepatocytes | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Kupffer cells | NS | NS | NS | 1+ |

| Spleen | ||||

| Macrophages | NS | NS | 1+ | 2+ |

| Sinus lining cells | NS | NS | 1+ | 1+ |

| Bone | ||||

| Osteocytes | NS | Trace | 1+ | 1+ |

| Macrophages | NE | 1+ | 1+ | 1+ |

| Brain | ||||

| Cortical neurons | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ |

| Hippocampal neurons | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ |

| Purkinje cells | 1+ | 1+ | 2+ | 2+ |

| Glia | Trace | 1+ | 1+ | 1+ |

| Eye | ||||

| Retinal pigment epithelium | NS | Trace | Trace | 1+ |

| Inner cell layer | NS | NS | Trace | 1+ |

| Outer cell layer | NS | NS | Trace | NS |

| Heart | ||||

| Endothelial and valve cells | NE | NE | NE | 1+ |

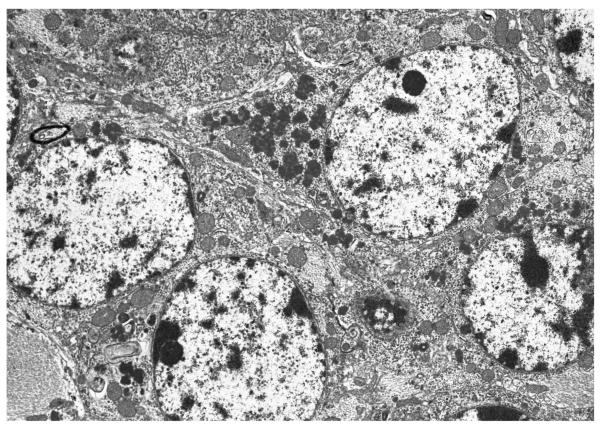

In glomeruli, visceral and parietal glomerular epithelial cells and occasional mesangial cells had well circumscribed membrane bound accumulation of GRODs by 3 – 5 months of age and the amount of storage increased progressively in 3, 5 and 7 month old PPT1 −/− mice (Figure 1A and B, Table 1). Tubular epithelial cells in PPT −/− mice had no osmiophilic storage at any age.

Fig. 1 A and B.

Glomerular visceral and parietal epithelial cells from a 5 month old (A) and Glomerular mesangial cell from a 7 month old (B) PPT −/− mouse have membrane bound electron-dense coarse granular cytoplasmic storage (asterix). (A and B: uranyl acetate-lead citrate, A 8,300X and B 6,600X magnification)

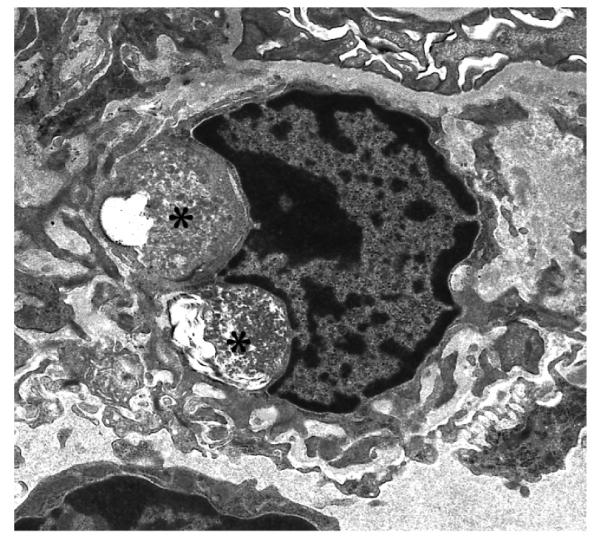

Large macrophages and rare sinus lining cells in the spleen and Kupffer cells in the liver had storage in older PPT1 −/− mice (Figure 2, Table 1), but splenic lymphocytes and hepatocytes had no storage apparent by light or electron microscopy. There was no evidence of lysosomal storage material in spleens or livers from PPT −/−mice younger than 5 months of age.

Fig. 2 A and B.

Rare sinus lining cells in the spleen (A) and Kupffer cells (B) in the liver have electron-dense granular storage (asterix) in an adult PPT1 −/− mouse. (A and B: uranyl acetate-lead citrate, A 10,000X and B 6,600X magnification)

Rare osteocytes in bone from 3, 5 and 7 month old PPT1 −/− mice had a small amount of storage. There was no storage in bone marrow cells or in chondrocytes and bone architecture appeared normal by light microscopy.

Lysosomal storage material was most prominent in the CNS. Ultrastructural evidence of CNS storage was present as early as 1 month of age and then accumulated progressively with aging. Neocortical neurons, hippocampal pyramidal neurons and Purkinje cells had abundant lysosomal storage of GROD (Figure 3) and a lesser amount of storage was present in glial and endothelial cells (Figure 4A and B). Additional cellular changes of neuronal loss, astrocytosis and prominent histiocytes were present in the CNS at 5 and 7 months. The neuronal loss affected the cerebral neocortex (Figure 5) and hippocampal pyramidal cell layers. Astrocytosis was present in these areas as well as in the cerebral and cerebellar white matter. The eyes from PPT −/− mice had GROD lysosomal storage in scleral fibroblasts, retinal pigment epithelium, and retinal neurons most prominent in the oldest mice examined.

Fig. 3 A and B.

Neocortical neurons (A) and hippocampal pyramidal neurons (B) from a 7 month old PPT −/− mouse have abundant lysosomal storage of GROD in the cytoplasm. (A and B: uranyl acetate-lead citrate, A 5,000X and B 10,560X magnification)

Fig. 4 A and B.

A. Storage is present in glial cells throughout the central nervous system in PPT −/− mice. In the neocortex, a glial cell (A) from an adult PPT −/− mouse has abundant cytoplasmic GROD. B. Endothelial cells, here in the brain of a 7 month old PPT −/− mouse, also contain lysosomal storage. (A and B: uranyl acetate-lead citrate, A 6,600X and B 10,000X magnification)

Fig. 5 A and B.

A. The parietal neocortex from a normal wild-type 7 month old mouse is of normal thickness. The meningeal surface is on the top of the figure and the white matter tract of the corpus callosum is at the lower aspect of the figure. B. The same region of the parietal neocortex from a 7 month old PPT −/− mouse shows atrophy with a marked decrease in thickness of the neocortical layer. (A and B: Toluidine blue, bar = 100 microns)

In the heart, endothelial cells and occasional valve stromal cells contained GROD lysosomal storage in the 7 month old mice. Very rare small GROD accumulations were also present in myocardial cells. Samples of tissue from the media of the aortic arch showed abundant GROD in smooth muscle cells in 7 month old PPT mice (Figure 6).

Fig. 6.

The media of the aortic arch has abundant GROD in lysosomes in smooth muscle cells in an adult PPT −/− mouse. This storage may contribute to the aortic dilatation apparent by ultrasound. (uranyl acetate-lead citrate 5,000X magnification)

Clinical cardiac abnormalities and morphological abnormalities have been described in patients with NCLs as well as in the canine model of NCL (9;21). To characterize the cardiovascular phenotype in PPT1 −/− mice, a comprehensive non-invasive echocardiographic examination of the heart and ascending aorta was performed by a high-resolution ultrasound system (spatial resolution ~ 100 micron). Results are summarized in Table 2. Although the difference in body weights did not reach statistical significance between wild type and PPT1 −/− mice used in the ultrasound studies, it is well recognized that PPT1 −/− mice have smaller body mass, therefore, linear measurements of the left ventricle (LV) and aorta were indexed to body weight. Two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography was used to evaluate LV structure and function. Measurements of LV wall thickness and chamber dimension showed a trend toward increased values in the PPT1 −/− mice, and calculated values based on these measurements revealed significantly increased LV mass index in comparison with wild type controls (4.0±0.3 mg/g vs. 3.6±0.3 mg/g, p<0.05). Non-invasive parameters of LV systolic function (FS, VCFC) showed no significant difference between the groups. To evaluate diastolic function of the LV, Doppler echocardiography was performed to measure trans-mitral blood flow velocities. There was no significant difference detected between the groups in respect to early or late (atrial) absolute filling velocities (data not shown) or the ratio of these values (E/A, Table 2). To characterize physiologically significant valvular involvement, Doppler echocardiography was performed to evaluate the presence of aortic and mitral stenosis and regurgitation. Pulse-wave Doppler mapping of proximal and distal trans-valvular flow velocities showed no evidence of significant valvular abnormalities (data not shown).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic characterization of cardiovascular structure and function.

| WT | PPT1 KO | |

|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 26.7±2.7 | 24.4±2.3 |

| HR (bpm) | 446±23 | 432±44 |

| LV Parameters | ||

| LVWdI (mm/kg) | 28.1±2.5 | 30.7±1.4 |

| LVIDdI (mm/kg) | 139.1±13.5 | 155.0±15.5 |

| LVMI (mg/g) | 3.6±0.3 | 4.0±0.3* |

| FS (%) | 36.8±4.2 | 34.5±2.3 |

| VCFC | 8.8±1.4 | 8.9±0.6 |

| E/A | 1.2±0.2 | 1.3±0.2 |

| Aortic Parameters | ||

| SOVDI (mm/kg) | 71.0±6.1 | 87.1±11.5* |

| STJDI (mm/kg) | 57.8±4.9 | 66.9±8.5* |

| AscAoDI (mm/kg) | 60.0±4.1 | 67.8±6.9* |

BW, body weight in grams; HR, heart rate in beats per minute; LVWdI, end-diastolic left ventricular wall thickness indexed to body weight; LVIDdI, end-diastolic internal diameter of the left ventricular indexed to body weight; LVMI, left ventricular mass indexed to body weight; FS, left ventricular fractional shortening; VCFC, velocity of circumferential shortening of the left ventricle; E/A, ratio of the early over late (atrial) velocity of trans-mitral diastolic blood flow; SOVDI, internal diameter of the ascending aorta at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva indexed to body weight; STJDI, internal diameter of the ascending aorta at the level of the sinu-tubular junction indexed to body weight; AscAoDI, internal diameter of the ascending aorta at the level immediately proximal to the innominate artery indexed to body weight.

p < 0.05.

To non-invasively evaluate in vivo aortic structure, two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography was used to measure the diameter of the ascending aorta from orthogonal views at multiple levels. These measurements showed significantly increased luminal diameters of the aorta in the PPT1 −/− mice at three different levels of the ascending aorta, most significantly at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva; even the non-indexed absolute values were significant at this level (Figure 7).

Fig. 7 A and B.

A. Ultrasound evaluation of the aortic root of a normal wild type mouse shows the normal caliber of the aorta. Arrows: valve leaflets, arrow heads: aortic root wall at sinus of Valsalva. B. There was significantly increased luminal diameter of the aorta in a PPT1 −/− mouse, most prominent at the level of the sinuses of Valsalva. Arrows: valve leaflets, arrow heads: aortic root wall at sinus of Valsalva.

Discussion

INCL is a LSD that causes widespread progressive neurodegenerative changes with cerebral atrophy. The murine model of PPT1 deficiency shares many clinical features with INCL including seizures and progressive motor and visual deficits. The storage material in the mice is morphologically identical to that seen in children with INCL. This model has been previously shown to have a thickened calvarium and autofluorescent lysosomal storage in neurons and glial cells in the cerebral cortex, cerebellar Purkinje and granular cell layers, hippocampus, thalamus and hypothalamus, dentate nucleus, pons and regions of the medulla (14;15). The cortex and hippocampus are atrophic. Neurons in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex and Purkinje cell layer have ballooning degeneration and apoptosis with gliosis (13). In the eye, there is progressive disorganization of the retina with pronounced thinning of the outer nuclear layer with aging. The number of photoreceptors in the outer nuclear layer decreases with age and macrophage-like cells infiltrate the retina in INCL mice (18).

Previous descriptions of CNS and eye morphology in PPT1 −/− mice have documented the occurrence of widespread autofluorescent storage and cell loss in the CNS accompanied by astrocytosis. This is the first description of the ultrastructural appearance and progressive nature of CNS storage in this murine model of INCL. The GROD in PPT1 −/− mice was similar in ultrastructural appearance to that observed in human INCL (22). Increasing accumulation of storage in the CNS and retina of PPT1−/− mice with age correlates with reports of progressive severity of motor dysfunction and visual defects in these animals (18).

We report here for the first time ultrastructural evidence of widespread storage in nonneural tissues in a murine model of INCL. Previous descriptions of storage within viscera in PPT1 −/− mice have been limited to identification of autofluorescent histiocytes in the spleen (13). Here we report GROD in every tissue examined. In particular, prominent progressive storage was observed in glomerular visceral and parietal epithelial cells and in mesangial cells and in smooth muscle cells in the media of the aorta. The visceral storage we observed could become clinically relevant if treatments to correct CNS storage are successful.

We extend previous observations of the morphological changes observed in the PPT1 −/− mouse model of INCL to include ultrastructural changes and evaluation of cardiac structure and function by ultrasound. The dilatation of the aortic root reported here could be due to primary structural abnormalities such as perturbations of the elastic lamina related to the abundant GROD observed in the smooth muscle cells. It has been demonstrated previously that the elastic lamina is disrupted by lysosomal storage material that accumulates in the aorta of mice with MPS I (23). Future detailed study of the architecture of the elastic fibers in the aorta may provide evidence of alteration in PPT −/− mice, but our review failed to show any significant alteration. Dilatation of the aorta can also result as secondary changes from hemodynamic alterations associated with valvular abnormalities such as post-stenotic dilatation which occurs with aortic stenosis. However, we did not detect hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis, and thus we propose that the mild aortic dilatation observed in the PPT1 −/− mice is likely related to structural abnormalities of the aortic wall. Similarly, the increase in left ventricular mass may be due to accumulation of GROD storage in the myocardium or secondary to hemodynamic stress. There was no detectable mitral regurgitation and no significant aortic valve insufficiency or stenosis in the PPT1−/− mice; therefore, pressure or volume overload was not identified as a cause of the LV hypertrophy. Others have observed left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with NCL (24;25) but clinical evidence of aortic dilatation in these disorders has not been well described.

The cardiac findings in the PPT1−/− mice are consistent with anatomical and histological findings in the hearts of children with NCLs. Cardiac pathology is a common finding in a number of lysosomal storage diseases (26). Post mortem analysis of the hearts of several children with NCL, one with GROD, demonstrated the accumulation of ceroid pigment in the muscle and valves with accompanying left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis (9;27). Interestingly, the extent of cardiac disease appears to be more pronounced in children with the more protracted forms of NCL such as JNCL (9;27). Therefore, we believe that mouse model of INCL described here may have clinically relevant cardiac disease that would become more pronounced if CNS disease was effectively treated and the animals lived longer.

Our detailed description of progressive accumulation of storage in the PPT1 −/− murine model of INCL provides a practical benchmark for evaluation of the efficacy of various therapies in correcting the cellular alterations caused by PPT1 deficiency in the CNS and viscera of these animals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health and The Batten Disease Support and Research Association to MSS (DK57586 and NS43205)

References

- 1.Jalanko A, Tyynela J, Peltonen L. From genes to systems: new global strategies for the characterization of NCL biology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:934–944. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltonen L, Savukoski M, Vesa J. Genetics of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett MJ, Hofmann SL. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease): a new class of lysosomal storage diseases. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1999;22:535–544. doi: 10.1023/a:1005564509027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesa J, Hellsten E, Verkruyse LA, et al. Mutations in the palmitoyl protein thioesterase gene causing infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Nature. 1995;376:584–587. doi: 10.1038/376584a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffey M, Bible E, Vogler C, et al. Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated gene therapy decreases autofluorescent storage material and increases brain mass in a murine model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verkruyse LA, Hofmann SL. Lysosomal targeting of palmitoyl-protein thioesterase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15831–15836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu JY, Verkruyse LA, Hofmann SL. The effects of lysosomotropic agents on normal and INCL cells provide further evidence for the lysosomal nature of palmitoyl-protein thioesterase function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1583:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haltia M, Herva R, Suopanki J, et al. Hippocampal lesions in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(Suppl A):209–211. doi: 10.1053/eipn.2000.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofman IL, van der Wal AC, Dingemans KP, et al. Cardiac pathology in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses--a clinicopathologic correlation in three patients. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5(Suppl A):213–217. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2000.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonnqvist T, Vanhanen SL, Vettenranta K, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurology. 2001;57:1411–1416. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchison HM, Mole SE. Neurodegenerative disease: the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) Curr Opin Neurol. 2001;14:795–803. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200112000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Butler JD, Levin SW, et al. Lysosomal ceroid depletion by drugs: therapeutic implications for a hereditary neurodegenerative disease of childhood. Nat Med. 2001;7:478–484. doi: 10.1038/86554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta P, Soyombo AA, Atashband A, et al. Disruption of PPT1 or PPT2 causes neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13566–13571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251485198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bible E, Gupta P, Hofmann SL, et al. Regional and cellular neuropathology in the palmitoyl protein thioesterase-1 null mutant mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:346–359. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kielar C, Maddox L, Bible E, et al. Successive neuron loss in the thalamus and cortex in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woloszynek JC, Roberts M, Coleman T, et al. Numerous transcriptional alterations in liver persist after short-term enzyme-replacement therapy in a murine model of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Biochem J. 2004;379:461–469. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffey MA, Wozniak D, Wong M, et al. CNS-directed AAV2-mediated gene therapy ameliorates functional deficits in a murine model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Mol Ther. 2006;13:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffey M, Macauley SL, Ogilvie JM, et al. AAV2-mediated ocular gene therapy for infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Mol Ther. 2005;12:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta P, Soyombo AA, Shelton JM, et al. Disruption of PPT2 in mice causes an unusual lysosomal storage disorder with neurovisceral features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12325–12330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033229100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalanko A, Vesa J, Manninen T, et al. Mice with Ppt1Deltaex4 mutation replicate the INCL phenotype and show an inflammation-associated loss of interneurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong D, Lombard C, Ellis A. Electrocardiographic and histologic abnormalities in canine ceroid-lipofuscinosis (CCL) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1986;18:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(86)80986-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santavuori P, Gottlieb I, Haltia J, et al. In: CLN1 Infantile and Other Types of NCl with GROD in the Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinuses (Batten Disease) Goebel HHaeal., editor. IUS Press; 1999. pp. 16–36. C. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Xu L, Hennig AK, et al. Liver-directed neonatal gene therapy prevents cardiac, bone, ear, and eye disease in mucopolysaccharidosis I mice. Mol Ther. 2005;11:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reske-Nielsen E, Baandrup U, Bjerregaard P, et al. Cardiac involvement in juvenile amaurotic idiocy--a specific heart muscle disorder. Histological findings in 13 autopsied patients. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [A] 1981;89:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1981.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michielsen P, Martin JJ, Vanagt E, et al. Cardiac involvement in juvenile ceroid lipofuscinosis of the Spielmeyer-Vogt-Sjogren type: prospective noninvasive findings in two siblings. Eur Neurol. 1984;23:166–172. doi: 10.1159/000115699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilbert-Barness E. Review: Metabolic cardiomyopathy and conduction system defects in children. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2004;34:15–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomiyasu H, Takahashi W, Ohta T, et al. An autopsy case of juvenile neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis with dilated cardiomyopathy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2000;40:350–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]