Abstract

Sexual minorities are at increased risk for multiple mental health burdens compared to heterosexuals. The field has identified two distinct determinants of this risk, including group-specific minority stressors and general psychological processes that are common across sexual orientations. The goal of the present paper is to develop a theoretical framework that integrates the important insights from these literatures. The framework postulates that (a) sexual minorities confront increased stress exposure resulting from stigma; (b) this stigma-related stress creates elevations in general emotion dysregulation, social/interpersonal problems, and cognitive processes conferring risk for psychopathology; and (c) these processes in turn mediate the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychopathology. It is argued that this framework can, theoretically, illuminate how stigma adversely affects mental health and, practically, inform clinical interventions. Evidence for the predictive validity of this framework is reviewed, with particular attention paid to illustrative examples from research on depression, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders.

Keywords: stigma-related stress, general psychological processes, mediation, LGB populations, mental health disparities

Epidemiological research has revealed multiple mental health burdens among sexual minority1 populations, relative to heterosexuals (Cochran, 2001). Having established this risk, two separate literatures have focused on identifying factors creating this risk. The first literature has focused on group-specific processes, in the form of sexual minority stress (Meyer, 2003), whereas the second literature has emphasized general psychological processes (Diamond, 2003; Savin-Williams, 2001) that explain the development of psychopathological outcomes in both sexual minorities and heterosexuals. The field now requires a framework that draws on and integrates the important insights gained from these three distinct literatures: (a) psychiatric epidemiology; (b) social generation of stigma through stress; and (c) general psychological processes. The goal of the present paper is the development of such a framework that elucidates potential psychological pathways linking stigma-related stressors to adverse mental health outcomes. The paper’s central premise is that a comprehensive framework of mental health disparities must take into account both group-specific stressors and general psychological processes. Indeed, exclusive focus on either of these processes alone—without consideration of their interrelationships—may hinder the development of effective theory on the determinants of mental health disparities among sexual minorities, as well as prevention and intervention efforts with this population.

The psychological mediation framework advanced in this paper proposes three primary hypotheses: (a) sexual minorities confront increased stress exposure resulting from stigma; (b) this stigma-related stress2 creates elevations (relative to heterosexuals) in general coping/emotion regulation, social/interpersonal, and cognitive processes conferring risk for psychopathology; and (c) these processes in turn mediate the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychopathology. This framework is theoretically grounded in transactional definitions of stress (Monroe, 2008), which posit that both environmental and response (i.e., appraisals) components of stress are important in determining health outcomes. In identifying the psychological processes that stigma-related stress initiates, this framework also draws upon insights from the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), which provided an elegant synthesis of the role of stress in the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations.

Despite these complementary approaches, the psychological mediation framework advanced in the present paper differs in several important respects from the minority stress theory. The first distinction relates to where stress is situated within these two models. The minority stress theory describes how societal stressors contribute to mental health disparities in LGB populations (Meyer, 2003). According to this theory, stress is a mediator in the relationship between social structure/status and illness (i.e., status → stress → psychopathology). However, as noted by Monroe (2008) in his recent review of the general stress literature, “In a strange and circular way, stress seems to stand on its own as a plausible, complete, self-contained explanation” (p. 47). This indictment of the general stress literature is also germane to research on minority stress, as it points to the need for mediational research explaining how stigma-related stressors “get under the skin” and lead to psychopathology.

The psychological mediation framework, in contrast, examines the intra- and interpersonal psychological processes through which stigma-related stress leads to psychopathology. Consistent with research from the general literature on stressors (e.g., Grant, Compas, Stuhlmacher, Thurm, MacMahon, & Halpert, 2003), this framework takes stress as an initial starting point (i.e., risk factor) in the causal chain leading to psychopathology (i.e., stress → psychological mediators → psychopathology). This approach then focuses on isolating the emotion regulation, social, and cognitive processes that stigma-related stress causes. Meyer’s (2003) comprehensive review of minority stress specifically identified this research question as the crucial next step in the literature on mental health disparities in LGB populations: “To understand causal relations, research needs to explain the mechanisms through which stressors related to prejudice and discrimination affect mental health” (p. 689–690; emphasis added).

A second, related distinction between the minority stress theory and the psychological mediation framework has to do with the inclusion of “general” psychological processes, which refer to established cognitive, affective, and social determinants of mental health outcomes.3 The minority stress theory focuses on the group-specific processes that sexual minorities confront as members of a stigmatized group, in the form of distal and proximal stressors resulting from their minority status. As Meyer (2003) states, an “underlying assumption” of the theory is that minority stress is “unique—that is, minority stress is additive to general stressors that are experienced by all people, and therefore, stigmatized people require an adaptation effort above that required of similar others who are not stigmatized” (p. 676).

An alternative approach to assessing characteristics that distinguish sexual minorities from their heterosexual peers (i.e., minority stress) has been to examine the numerous general psychological processes that these groups share (Diamond, 2003; Savin-Williams, 2001). Importantly, clinical research from this approach has demonstrated that general psychological processes conferring risk for psychopathology are elevated in sexual minorities relative to heterosexuals (e.g., Austin, Ziyadeh, Fisher, Kahn, Colditz, & Frazier, 2004; Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). This literature on general psychological processes was absent from the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), given its emphasis on group-specific stressors. Consequently, the minority stress theory overlooked an entire class of risk factors that appear to be important in explaining disparities in psychiatric morbidity among LGB populations. The psychological mediation framework proposed here incorporates the literature on general psychological processes and demonstrates that these processes are set in motion by stigma-related stress and mediate the stress-psychopathology association.

Finally, the psychological mediation framework has important implications for interventions that are not addressed in the minority stress theory. The minority stress theory points to interventions at a societal level, including stigma reduction and policies that eliminate structural forms of prejudice and discrimination (Meyer, 2003). These kinds of interventions are important and much needed. Nevertheless, a substantial body of research indicates that changes at the structural level are protracted (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2000; Hinshaw & Stier, 2008) and, in some cases, may not be effective (Kalev, Dobbin, & Kelly, 2006). As Meyer (2003) noted, “Purported shifts in the social environment have so far failed to protect LGB youth from prejudice and discrimination and its harmful impact” (p. 690). Consequently, individual-level clinical interventions that address mental health morbidity among individuals currently suffering from stigma-related stressors are also needed.

The importance of targeting the role of stigma-related stressors in clinical work with sexual minority clients has been recognized for some time (e.g., Division 44/Committee on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Concerns Joint Task Force, 2000). However, because the minority stress theory did not focus on the psychological processes through which stigma-related stress contributes to psychopathology, it remains unclear what processes should be the target of clinical interventions with sexual minority clients. Research emerging from the psychological mediation framework, in contrast, points to several psychological processes that are amenable to intervention, including emotion dysregulation (e.g., rumination-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT); see Watkins et al., 2007), pessimism/hopelessness (e.g., CBT; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), and, in the area of alcohol use disorders, positive alcohol expectancies (Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001). As such, this framework provides novel information that may contribute to the development of clinical interventions that can reduce disparities in LGB populations, a central priority of Healthy People 2010 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

The remainder of the paper builds an argument for the development of this theoretical framework. In the following sections, research on established risk factors—including group-specific stressors and general psychological processes—is briefly synthesized. Because aspects of these literatures have been reviewed elsewhere (Meyer, 2003; Diamond, 2003), I provide a selective review of illustrative research in order to update work since these reviews were published and to highlight research that is germane to the development of the psychological mediation framework. Next, I discuss research on the psychological mediation framework, with particular attention paid to ways in which the framework advances our understanding of the important contributions from prior research. I then review evidence for the framework’s predictive validity, highlighting research on depression, anxiety and alcohol use disorders. The paper concludes with directions for future research that address specific aspects of the framework requiring further evidence, as well as implications for prevention and intervention work that seeks to reduce disparities in psychiatric morbidity among sexual minorities.

Epidemiology of Risk

Early studies with sexual minorities had significant methodological limitations, including sampling issues (i.e., reliance on non-probability samples) and lack of appropriate comparison groups. More recently, studies improving upon these limitations have revealed consistent disparities in the mental health of sexual minorities relative to heterosexuals. A recent meta-analysis found that sexual minorities are two-and-a-half times more likely to have a lifetime history of mental disorder compared with heterosexuals, and twice as likely to have a current mental disorder (Meyer, 2003). Below, population- and community-based studies demonstrating these disparities across internalizing and externalizing domains are briefly reviewed.

Sexual minority adults appear to be at increased risk for psychiatric morbidity across a wide spectrum of internalizing outcomes, including depression and anxiety disorders (Cochran & Mays, 2000a; 2000b; Cochran, Mays, & Sullivan, 2003; Gilman, Cochran, Mays, Ostrow, & Kessler, 2001; Sandfort, deGraaf, Bijl, & Schnabel, 2001). These disparities emerge early in the life course, with LGB young adults (Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999; Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005) and sexual minority youth (D’Augelli, 2002; Fergusson et al., 1999; Fergusson et al., 2005; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Lock & Steiner, 1999; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Safren & Heimberg, 1999) exhibiting elevated symptomatology compared to heterosexuals.

Disparities in externalizing disorders are also consistently found in the literature. Sexual minority youth have higher rates of externalizing behaviors, including alcohol, tobacco use, and poly-substance use (Garofalo, Wolf, Kessel, Palfrey, & DuRant, 1998; Russell, Driscoll, & Truong, 2002; Ziyadeh et al., 2007), compared to heterosexuals. These disparities persist among young adults (Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a) as well as adults in general (Burgard, Cochran & Mays, 2005; Cochran, Keenan, Schober, & Mays, 2000; Drabble, Midanik, & Trocki, 2005).

Psychiatric comorbidity, early onset, and chronicity/persistence of disorder are important indicators of illness severity as well as adverse consequences (Aharonovich, Liu, Nunes, & Hasin, 2002; Hirschfield, Hasin, Keller, Endicott, & Wunder, 1990; Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998), and several recently published studies with representative samples suggest that sexual minorities have elevated risk in each of these domains. Sexual minorities have higher rates of comorbidity than heterosexuals (Cochran et al., 2003; Fergusson et al., 2005; Sandfort et al., 2001). It appears that sexual minorities may also have an earlier age of onset for certain disorders, namely depression among gay men and substance use disorders among lesbians (Gilman et al., 2001). Although only one general population study has examined chronicity of disorder, lesbians were found to have greater persistence of past-year substance use disorders than heterosexual women (Gilman et al., 2001). The presence of multiple co-occurring disorders, earlier onset, and greater persistence of disorder among sexual minorities is striking and highlights the need for evidence-based treatments to address the increased mental health burden in this community.

In sum, research from epidemiological studies has indicated that sexual minorities have increased prevalence of mental disorders (Meyer, 2003) and comorbid psychiatric conditions (Cochran et al., 2003; Fergusson et al., 2005), as well as earlier disorder onset and greater persistence (Gilman et al., 2001), at least among a subset of disorders. Despite the methodological improvements of these epidemiological studies over previous research, the small sample sizes of sexual minorities (typically under 100 participants) have reduced the ability to detect significant effects (e.g., persistence; Gilman et al., 2001) and to examine potentially important sub-group differences (e.g., sex; Fergusson et al., 1999). In addition, studies have used different operationalizations of sexual orientation (e.g., self-identification, sexual behavior), which can affect the observed relationships between same-sex sexual orientation and health outcomes (McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, & Boyd, 2005; Midanik, Drabble, Trocki, & Sell, 2007). Future research with larger samples of sexual minorities is needed to address these issues. The addition of questions assessing multiple dimensions of sexual orientation, including self-identification, sexual behavior, and attraction, to recent large-scale epidemiological surveys (e.g., Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Study and Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions) represents an important example of recent efforts to gather data on mental health outcomes in LGB populations (Sell & Becker, 2001).

Group-Specific vs. General Processes

Given the increased risk across multiple indicators of mental health burdens, researchers have turned to identifying factors that can explain this elevated risk in LGB populations. Two quite distinct classes of processes have been proposed to account for the higher rates of mental disorders among sexual minorities. The first focuses on unique, group-specific processes that sexual minorities confront as members of a stigmatized group. This approach, as reviewed in the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), emphasizes distal and proximal stress processes as predictors of psychopathology. The second approach examines the role of general psychological processes that have been shown to predict developmental and clinical outcomes in heterosexual samples (Diamond, 2003; Savin-Williams, 2001). Research emerging from this approach therefore focuses on common psychosocial processes that sexual minorities share with their heterosexual peers.

Group-Specific Processes

According to Meyer’s (2003) minority stress theory, sexual minorities are exposed to multiple forms of stressors, including discrimination, expectations of rejection, concealment/disclosure, and internalized homophobia. The minority stress theory draws upon the extensive literature documenting an association between stress and psychopathology (Brown, 1993; Dohrenwend, 2000) and is conceptually related to other social psychological and sociological theories that have highlighted the deleterious consequences of prejudice and stigma (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Link & Phelan, 2001). Just as general life stressors are believed to exceed an individual’s ability to cope (Dohrenwend, 2000; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), stigma creates several unique demands (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Major & O’Brien, 2005; Miller & Kaiser, 2001; Pachankis, 2008) that may prove to be especially stress-inducing. In turn, these additional stressors are hypothesized to account for disparities in rates of mental health problems among sexual minorities.

Although one longitudinal study has failed to document a relationship between sexual minority stress and changes in psychological distress (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002), an emerging body of empirical research indicates that stigma-related stress has deleterious consequences for behavioral and mental health outcomes among sexual minorities. Evidence of the association between specific stigma-related stressors and adverse mental health outcomes is briefly reviewed below. This review is organized around the distal-proximal distinction advanced in the minority stress model.

Distal stressors

Meyer (2003) defined distal stressors as prejudice-inspired events, including violence/victimization and discrimination. Several studies have documented increased exposure to these distal stressors in LGB populations (e.g., (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008). With respect to victimization, studies that include representative samples and heterosexual comparison groups document high rates of victimization among LGB adults (Corliss, Cochran, & Mays, 2002; Tjaden, Thoeness, & Allison, 1999). A particularly novel application of this methodology, published after Meyer’s (2003) review, used a comparison sample of heterosexual sibling(s) of the LGB proband (Balsam, Rothblum & Beauchaine, 2005). This study found a greater prevalence of multiple forms of victimization among the LGB participants, including both physical abuse and sexual assault. Studies of peer victimization among sexual minority youth have revealed similar trends, with this group at elevated risk for peer violence compared to their heterosexual peers (Russell, Franz, & Driscoll, 2001). Group differences in peer victimization partially account for the association between sexual orientation and multiple adverse mental health outcomes, including suicide risk (Russell & Joyner, 2001; Garofalo, Wolf, Wissow, Woods, & Goodman, 1999). Future studies are needed to determine whether this result is generalizable to specific classes of mental disorders.

Another distal stressor is experiences with discrimination based on sexual minority status. Several within-group studies have shown that perceived discrimination is predictive of multiple forms of mental health problems in LGB individuals, including psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008), anxiety (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 1999), and substance use disorders (McKirnan & Peterson, 1988; 1989). Between-group studies have also demonstrated greater discrimination among sexual minorities relative to heterosexuals. For instance, analyses of population-level data have shown that gay men earn 10–32% less than similarly qualified heterosexual men with the same job (Badgett, Lau, Sears, & Ho, 2007). Importantly, research with probability samples has documented increased exposure to discrimination experiences among LGB individuals relative to heterosexuals; when discrimination was statistically controlled, the association between sexual orientation and psychopathological outcomes was significantly attenuated (Mays & Cochran, 2001).

Proximal stressors

In contrast to distal stressors, proximal stressors are associated with identities that “vary in the social and personal meanings that are attached to them” (Meyer, 2003; p. 676–677). One such proximal stressor is self-stigmatization (Thoits, 1985), which involves a process of incorporating negative societal views of homosexuality into the self-concept. A review of self-stigmatization among sexual minorities—termed internalized homophobia—indicated significant relationships between self-stigma and adverse mental health outcomes (Williamson, 2000).

Two additional proximal stressors identified by Meyer (2003) include concealment and expectations of rejection. Homosexuality is a stigma that can be concealed. Although this can often serve a protective function, there are numerous ways in which concealment can lead to negative mental health outcomes, including hypervigilance, threat of discovery, and social isolation (Pachankis, 2008). One consequence of discrimination is that individuals begin to expect rejection based on their stigmatized identity (Mendoza-Denton, Downey, Purdie, Davis, & Pietrzak, 2002). Among sexual minorities, sensitivity to status-based rejection is predictive of both adverse physical (Cole, Kemeny & Taylor, 1997) and mental (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008) health outcomes.

General Psychological Processes

Whereas the minority stress theory focused almost exclusively on stress, an alternative emphasis has been on general psychological processes which, as previously mentioned, refer to established cognitive, affective, and social risk factors for mental health outcomes. Proponents of this approach have argued that the assumption underlying most research with sexual minorities is that the stressors they confront inevitably result in the clinical and developmental differences between heterosexuals and sexual minorities (Diamond, 2003; Savin-Williams, 2001). According to these researchers, the result has been an under-appreciation for the full range of normative psychological processes through which a sexual minority identity influences development and mental health (e.g., Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dubé, 1999).

Rather than assessing characteristics that distinguish sexual minorities from their heterosexual peers, this research instead examines the numerous psychological processes that these groups share. For example, researchers studying disparities in rates of suicide would evaluate whether general psychological processes associated with suicidal behavior in heterosexuals (e.g., substance use, depression, social support, family functioning) also predict increases in suicidal behavior among sexual minority youth. Factors that are unique to LGB status (e.g., age of awareness of homoerotic attractions, internalized homophobia) are rarely included in this approach. The principal proponents of general psychological processes have produced a line of research on the relationship between these processes and developmental trajectories of LGB adolescents, such as peer/romantic relationships (Diamond, 2003; Diamond et al., 1999). Other researchers have applied the study of general psychological processes to specific classes of psychopathology and risk behaviors in within-group analyses of sexual minorities (Savin- Williams & Ream, 2003; Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996).

Although this approach has confirmed the predictive validity of general psychological processes in the development of psychopathological outcomes, it cannot explain mental health disparities. In order to do so, this line of research must produce evidence from between-group analyses that the general psychosocial processes conferring risk for psychopathology are more prevalent among sexual minorities relative to heterosexuals. Currently, there is a growing body of research providing support for this point (see Table 1). Indeed, compared to heterosexuals, LGB populations exhibit elevations in general psychological risk factors, including hopelessness (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Safren & Heimberg, 1999), low self-esteem (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003; Ziyadeh et al., 2007), emotion dysregulation (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Matthews, Hughes, Johnson, Razzano, & Cassidy, 2002), social isolation (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Safren & Heimberg, 1999; Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003), permissive social norms for alcohol and tobacco use (Austin et al., 2004; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; Trocki, Drabble, & Midanik, 2005), and positive expectancies for drinking (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; Ziyadeh et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Support for Elevated General Psychological Processes in LGB Populations Relative to Heterosexuals

| Internalizing Psychopathology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Citation | Design/Sample | Predictor | Support? |

| Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008 | Longitudinal; 29 LGB and 1235 heterosexual adolescents (grades 6–8); representative, community-based sample | Emotion dysregulation (rumination and emotional awareness) | Yes. LGB had higher rumination and poorer emotional awareness. |

| Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006 | Cross-sectional; 2,255 sexual minority and 19672 heterosexual adolescents; representative sample of Minnesota youth | Family connectedness, teacher & adult caring, school safety | Yes. LGB had lower levels of all forms of support. |

| Matthews et al., 2002 | Cross-sectional; 583 lesbians and bisexuals and 270 heterosexual women; community-based sample from 3 urban cities | Coping (e.g., suppression, distraction) | Yes. Higher suppression and lower distraction among lesbians. |

| Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005 | Cross-sectional; 358 LGB and 267 matched heterosexual comparison; convenience sample | Hopelessness, self-esteem, social support | Yes. LGB were more hopeless, had lower self-esteem and lower support |

| Russell & Joyner, 2001 | Cross-sectional; 867 sexual minority and 11,073 heterosexual youth (grades 7–12); nationally representative survey (Add Health Study) | Hopelessness | Partial. Mean levels of hopelessness were higher in girls with same-sex attractions, but not boys. |

| Safren & Heimberg, 1999 | Cross-sectional; 56 LGB and 48 heterosexual youth; convenience sample | Social support, hopelessness | Yes. LGB had greater hopelessness and less social support. |

| Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003 | Longitudinal; 190 sexual minority and 2,734 heterosexual adolescents; nationally representative study | Global self-worth, low social support | Yes. Sexual orientation was associated with low self-worth and low social support |

| Substance Use | |||

| Citation | Design/Sample | Predictor | Support? |

| Austin et al., 2004 | Cross-sectional; 511 LGB and 9296 heterosexual adolescents; community-based population of adolescents living throughout U.S. | Social norms | Yes. More permissive social norms among lesbian/bisexual girls. |

| Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a | Longitudinal; 111 LGB and 2109 heterosexual young adults; representative, community-based sample | Social norms, positive alcohol expectancies | Yes. More permissive norms and greater alcohol expectancies among LGBs. |

| Trocki, Drabble, & Midanik, 2005 | Cross-sectional; 324 sexual minority men and women; national probability survey | Social norms (time spent in bars and parties) | Yes. Both sexual minority men and women spend more time in bars. |

| Ziyadeh et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional; 100 LGB adolescents; 9,631 heterosexual; nationally representative study | Self-esteem, positive alcohol expectancies | Yes. LGB had lower self-esteem and greater positive alcohol expectancies. |

Summary

Research has documented two broad classes of determinants of psychiatric morbidity in LGB populations. The first has focused on unique risk factors, in the form of stress exposure resulting from stigma-related processes. Several lines of evidence indicate that sexual minorities experience greater exposure to stress than heterosexuals—including workplace employment and discrimination (Badgett et al., 2007) and victimization (Balsam et al., 2005; Russell et al., 2001; Tjaden et al., 1999)—and that this increased stress exposure may account for higher rates of psychopathology among sexual minorities (Mays & Cochran, 2001).

An alternative approach has focused on common risk factors in the form of general psychological processes. Within-group studies have supported the role of these processes as predictors of psychopathological outcomes in sexual minorities (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in press; van Heeringen & Vincke, 2000; Walls, Freedenthal, & Wisneski, 2008). Moreover, between-group studies have shown that sexual minorities have higher levels of certain general psychological risk factors for psychopathology (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Safren & Heimberg, 1999), suggesting that general psychological processes may also be important for explaining disparities in psychopathology among LGB populations, relative to heterosexuals.

Although this research has provided important insights into the risk factors contributing to higher rates of psychopathology among sexual minorities, the field is left with several unanswered questions. In particular, what are the processes whereby group-specific stressors “get under the skin” and lead to disparities in psychiatric morbidity? Additionally, how do group differences in general psychosocial processes develop between sexual minorities and heterosexuals?

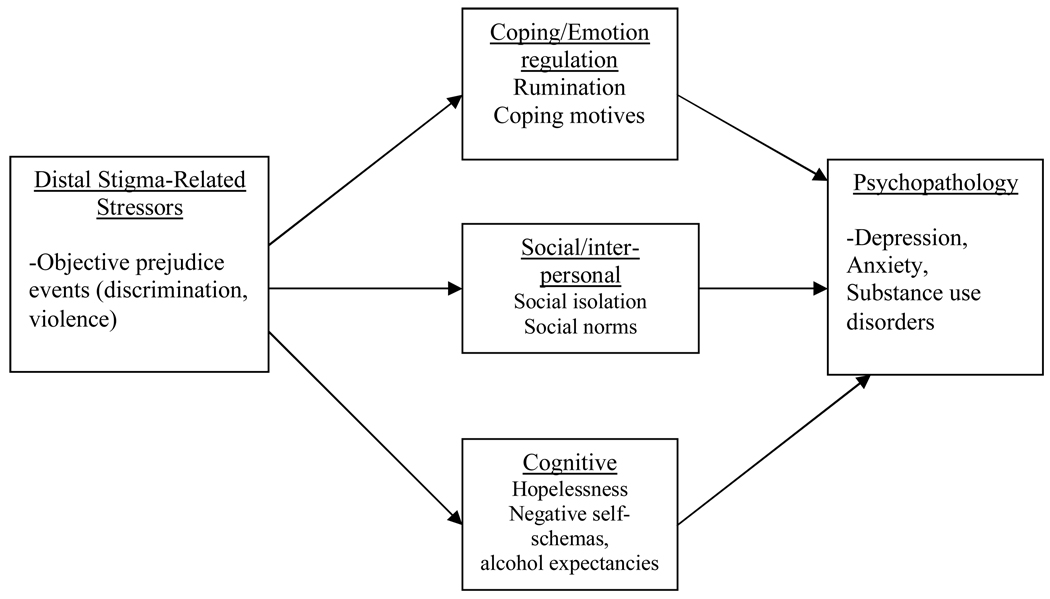

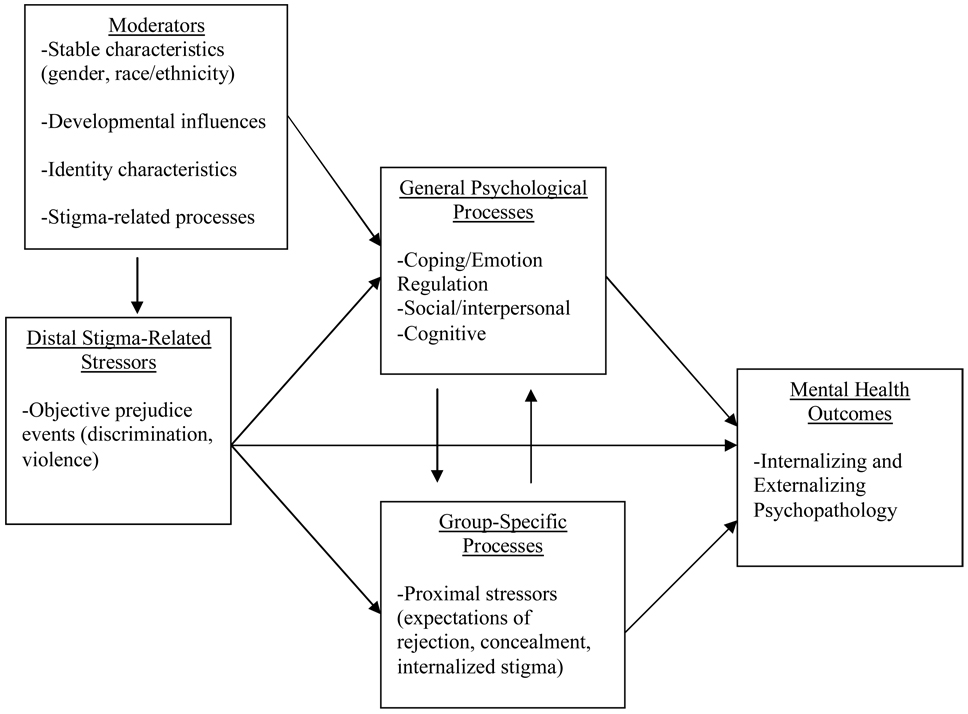

The Psychological Mediation Framework

In this section, I discuss the development of a psychological mediation framework to address these significant gaps in the knowledge base. As reviewed above, three distinct literatures on mental health burdens in LGB populations have emerged: (a) psychiatric epidemiology; (b) group-specific social stressors resulting from stigma; and (c) general psychological processes. To date, however, these literatures have largely been pursued separately, with little consideration of how group-specific and general psychological processes may jointly operate to produce disparities in psychopathology among sexual minorities. The psychological mediation framework proposed here synthesizes and integrates the key observations from these distinct literatures, highlighting the interrelationships among group-specific and general psychological processes in the development of mental health disparities. Specifically, the framework suggests that stigma-related stress renders sexual minorities more vulnerable to general psychological processes that are known to predict psychopathology in heterosexuals (see Figure 1). This integrative framework argues that one risk factor is a consequence of the other, and that both contribute to the pathogenesis of mental disorders in LGB populations. Additionally, this theoretical approach takes into account the unique stressors that sexual minorities confront, while also emphasizing the common vulnerabilities in psychological and social processes that sexual minorities and heterosexuals share. Thus, the novelty of the framework is that it simultaneously addresses how general psychological processes become initiated and how stigma-related stress leads to psychopathology, thereby providing an important theoretical and practical advancement toward understanding—and eventually reducing—mental health disparities in LGB populations.

Figure 1.

Psychological Mediation Framework

This psychological mediation framework is based on two lines of research. General stress models have identified stress-initiated psychological processes that may lead to mental health problems. For instance, the stress process model (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981) has identified two “mediating resources,” coping and social support, that people utilize in order to attenuate the effects of stressful life events. A more recent model linking chronic stress to health problems in youth (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002) proposes that the stress of growing up in a “risky” family environment leads to negative health outcomes in part through psychological pathways involving poor social competence and emotion regulation. Taken together, although these two models focus on somewhat different stressors, they both contend that stress initiates a cascade of responses that directly and indirectly lead to mental health problems. Although researchers have recognized that discrimination creates differential exposures to stress that may account for group disparities in mental health (e.g., Meyer, 2003; Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005), there are currently no models that explicate the general psychological processes through which social stressors related to sexual minority status ultimately produce mental health problems. The psychological mediation framework advanced in this paper therefore represents a particularly important application of general stress process models to the context of a distinct stressor (one that is related to stigma) and a specific understudied group (sexual minorities) evidencing disparities in stress-related psychiatric morbidity.

The second literature the psychological mediation framework draws upon is the social psychology of stigma. Beginning with the seminal work of Goffman (1963), social psychological research has been interested in understanding the negative effects of stigma. Much of the research that has emerged from this tradition has focused on adverse outcomes such as academic performance and self-esteem (for a review, see Major & O’Brien, 2005; see also Crocker et al., 1998) rather than the development of mental disorders per se. In addition, although this research has examined individual responses to discrimination and stigma (e.g., re-appraisal), the focus is often on group-level processes (e.g., disidentification) that protect against low self-esteem. The psychological mediation framework advanced in this paper extends this prior research in two important respects: (a) it focuses on processes previously shown to contribute to psychopathology, and (b) the outcomes of interest are specific classes of psychopathology.

Thus, adapting insights from existing stress process models and the stigma literature to LGB populations, the psychological mediation framework proposes three central hypotheses: (a) sexual minorities confront increased stress exposure resulting from stigma; (b) this stigma-related stress creates elevations (relative to heterosexuals) in general emotion dysregulation, social/interpersonal problems, and cognitive processes conferring risk for psychopathology; and (c) these processes in turn mediate the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychopathology.

In the following section, preliminary evidence for each of these hypotheses is reviewed, with particular attention paid to research on depression, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders, which are all elevated among LGB individuals according to a recent meta-analysis (Meyer, 2003). Although the minority stress theory makes predictions that are general and uniform across types of disorder (Meyer, 2003), the processes through which minority stress contributes to psychopathology may differ by disorder. Research on general psychological processes related to the development of psychopathology provides evidence in support of this position. For example, psychiatric and substance use disorders differ in symptoms, etiologic pathways, and the types of treatment that are appropriate, suggesting that they should be considered separately. Thus, although stigma-related stress is an important aspect of the integrative framework for all forms of psychopathology, discussion of the framework is organized around outcome to account for the different psychological processes through which this distal predictor is associated with clinical outcomes. Mental disorders are increasingly separated into “internalizing” and “externalizing” domains (e.g., Krueger, 1999). Thus, internalizing disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety) are discussed first, followed by externalizing disorders (i.e., alcohol use disorders).

Within each class of psychopathology, the primary components of the integrative framework are the psychosocial processes, which will constitute the focal point for discussion of the framework. Consistent with general stress models that have identified coping/emotion regulation, social, and cognitive mediators (Pearlin et al., 1981; Repetti et al., 2002), this section will be organized around those processes that are plausible sequelae of stigma-related stress.

Moderation versus Mediation Hypotheses

The psychological mediation framework seeks to gain a better understanding of the processes that can explain or account for the relation between stigma-related stressors and psychopathology among sexual minorities. Consequently, this research question requires theories and analyses of mediation, rather than moderation. It is important to note that some of the variables that we consider as mediators (e.g., social support) may also serve a moderating role. The crucial distinction, however, is that mediators are “activated, set off, or caused by” a stressor (Grant et al., 2003; p. 453) and therefore explain the relation between the predictor (i.e., stigma-related stressors) and the outcome (i.e., psychopathology) (Baron & Kenny, 1986). As explained by Grant and colleagues (2003), “Whereas moderators are characteristics of the individual and/or his or her social network prior to the stressor, mediators become characteristics of the individual and/or his/her social network in response to the stressor” (p. 453). Although the individual may possess some of the mediating characteristic prior to experiencing the stigma-related stressor, within a meditational framework the mediator will be significantly altered subsequent to experiencing the stressor (Grant et al., 2003). Applied to the current topic, it may be the case that LGB individuals engage in rumination before they are exposed to stigma-related stress, but the current framework posits that stigma-related stress will intensify ruminative self-focus following a stigma-related stressor; rumination will, in turn, statistically account for the association between stress and the development of depression.

Both mediators and moderators may be viewed as mechanisms that explain psychopathological outcomes, but my primary interest is in mediational processes that can explain why stigma-related stressors lead to psychopathology. This is in contrast to moderation analyses, in which the emphasis is on processes that increase or decrease the likelihood that stressors contribute to psychopathology (Grant et al., 2003). Although this review will focus on mediators, I devote a section to moderation in the future directions section, given the importance of questions of moderated mediation to the present research.

Depression and Anxiety Disorders

Stigma-related stress appears to create a cascade of responses that increase risk for depression and anxiety (see Table 2). There are other psychosocial processes that may mediate the relationship between stigma-related stress and internalizing disorders, such as fewer opportunities for romantic involvement (Diamond et al., 1999). However, this paper focuses on processes that have the strongest empirical support as risk factors for psychopathology, that are the most plausible sequelae of stigma-related stress, and that are amenable to clinical intervention.

Table 2.

General Psychosocial Processes as Mediators of the Association between Sexual Orientation and/or Stigma-related Stress and Psychopathology

| Between-Group Studies of LGB and Heterosexuals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation | Design/Sample | Stressor/Status | Mediator(s) | Outcome | Results consistent with mediation? |

| Coping/Emotion Regulation | |||||

| Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008 | Longitudinal; 29 LGB and 1235 heterosexual adolescents (grades 6–8); representative, community-based sample | Sexual Minority Status (same-sex attraction) | Emotion dysregulation (rumination and emotional awareness) | Depressive and anxiety symptoms | Yes |

| Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008b | Cross-sectional; 111 LGB and 2275 heterosexual young adults; representative, community-based sample | Stressor (Discrimination) | Coping motives | Alcohol-related problems | Yes |

| Matthews et al., 2002 | Cross-sectional; 583 lesbians and bisexuals, 270 heterosexual women; community-based sample from 3 urban cities | Sexual minority status (sexual attraction and behavior) | Coping (e.g., suppression, distraction), emotionality | Suicidality and depressive distress (treatment for depression) | No |

| Safren & Heimberg, 1999 | Cross-sectional; 56 LGB and 48 heterosexual youth; convenience sample | Sexual minority status (self-identification as LGB) | Acceptance coping (e.g., reappraisal) | Depressive symptoms, suicidality | Partial mediation for suicide; full mediation for depression |

| Social/interpersonal | |||||

| Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006 | Cross-sectional; 2,255 sexual minority and 19672 heterosexual adolescents; representative sample of Minnesota youth | Sexual minority status (sexual behavior) | Family connectedness, teacher & adult caring, school safety | Suicidality | Yes |

| Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003 | Cross-sectional; 630 LGB college students; national random sample | Sexual minority status (self-identification as LGB) | Social norms, social support (campus LGB resources) | Alcohol use (binge drinking); tobacco use | Reduction in association between LGB status and substance use not tested. |

| Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a | Longitudinal; 111 LGB and 2109 heterosexual young adults; representative, community-based sample | Sexual minoritystatus (self-identification as LGB and sexual behavior) | Social norms | Alcohol use | Yes |

| Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005 | Cross-sectional; 358 LGB and 267 matched heterosexual comparison; convenience sample | Sexual minority Status (attraction, behavior and identification) | Social support (from family) | Suicidality | Yes |

| Safren & Heimberg, 1999 | Cross-sectional; 56 LGB and 48 heterosexual youth; convenience sample | Sexual minority status (self-identification as LGB) | Social support | Depressive symptoms, suicidality | Partial mediation for suicide; full mediation for depression |

| Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003 | Longitudinal; 190 sexual minority and 2,734 heterosexual adolescents; nationally representative study | Sexual minority status (sexual behavior) | Social support | Suicide attempts | No |

| Cognitive | |||||

| Austin et al., 2004 | Cross-sectional; 511 LGB and 9296 heterosexual adolescents; community-based population of adolescents living throughout U.S. | Sexual minority status (feelings of attraction) | Self-esteem | Tobacco use and dependence. | No. |

| Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008b | Cross-sectional; 111 LGB and 2275 heterosexual young adults; representative, community-based sample | Stressor (Discrimination) | Positive alcohol expectancies | Alcohol-related problems | Yes |

| Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005 | Cross-sectional; 358 LGB and 267 matched heterosexual comparison; convenience sample | Sexual minority status (attraction, behavior and identification) | Hopelessness, self-esteem | Suicidality | Yes |

| Russell & Joyner, 2001 | Cross-sectional; 867 sexual minority and 11,073 heterosexual youth (grades 7–12); nationally representative survey (Add Health Study) | Sexual minority status (same-sex attraction) | Hopelessness | Suicide | Partial reduction in association between sexual minority status and suicidal thoughts and behaviors |

| Safren & Heimberg, 1999 | Cross-sectional; 56 LGB and 48 heterosexual youth; convenience sample | Sexual minority status (self-identification as LGB) | Hopelessness | Depressive symptoms, suicidality | Partial mediation for suicide; full mediation for depression |

| Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003 | Longitudinal; 190 sexual minority and 2,734 heterosexual adolescents; nationally representative study | Sexual minority status (sexual behavior) | Global self-worth | Suicide attempts | No |

| Ziyadeh et al., 2007 | Cross-sectional; 100 LGB adolescents; 9,631 heterosexual and “mostly heterosexual”; nationally representative study | Sexual minority status (attraction and identification) | Positive alcohol expectancies, self-esteem | Alcohol use behaviors | Partial (for girls, but not boys); results not consistent for all alcohol outcomes |

| Within-Group Studies of LGB individuals | |||||

| Citation | Design/Sample | Stressor | Mediator(s) | Outcome | Results consistent with mediation? |

| Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001 | Cross-sectional; 912 adult Latino gay men; probability sample from 3 cities | Discrimination | Social isolation | Psychological distress (depression and anxiety) | Yes |

| Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, in press | Longitudinal (experience sampling study); 31 LGB young adults; convenience sample | Stigma-related stress (discrimination, rejection sensitivity, felt stigma) | Rumination, suppression, social isolation | Psychological distress | Support for rumination and social isolation; Suppression occurred more on days when stigma stressors were reported, but did not mediate the stigma-distress association |

| Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in press | Longitudinal; 74 bereaved gay men; convenience sample | Perceived danger | Rumination, social support, pessimism | Depressive and anxiety symptoms | Yes |

| Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995 | Cross-sectional; 165 LGB young adults (aged 15–21); convenience sample | Victimization | Family support, self-acceptance (self esteem and comfort with gay identity) | Psychological distress and suicidality | Partial (support for psychological distress but not for suicidality) |

| Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996 | Cross-sectional; 136 gay and bisexual male youths; convenience sample | Gay-related stress | Self-esteem | Emotional distress; problem behaviors | No |

| Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003 | Cross-sectional; 681 sexual minority male youth; on-line convenience sample | Gay-related stressors and identity variables (victimization, disclosure, gender expression) | Self-esteem | Suicide attempts | Yes |

Coping and emotion regulation processes

Maladaptive coping/emotion regulation is one potential psychological process that is initiated by exposure to chronic stigma-related stress. Emotion regulation refers to the “conscious and nonconscious strategies we use to increase, maintain, or decrease one or more components of an emotional response” (Gross, 2001). Emotion regulation deficits are risk factors for depression (e.g., Rottenberg, Kasch, Gross, & Gotlib, 2002) as well as anxiety disorders (e.g., Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005).

Because stigma conveys a devalued social identity within a particular context (Crocker et al., 1998), it creates unique stressors that contribute to negative affect (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Stigmatized individuals must therefore use strategies to effectively manage these emotional responses. Current research, including the minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003), has examined coping as a moderator of the stigma-health association.

In contrast, the psychological mediation framework conceptualizes coping/emotion regulation as a mediator of the stress-psychopathology relationship. Specifically, stress is hypothesized to result in maladaptive coping and emotion regulation strategies that in turn confer risk for psychopathology. Studies have indicated that chronic life stressors can lead to emotion regulation deficits (for a review, see Cicchetti & Toth, 2005), including increased sensitivity to anger (Davies & Cummings, 1998), difficulty understanding negative affect (Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000), and inappropriate expression of emotions (Camras, Ribordy, Hill, Martino, Spaccarelli, & Stefani, 1988). The relationship between chronic stress and emotion regulation deficits suggests the possibility that stigma-related stressors might also lead to emotion regulation deficits among sexual minorities. How might this occur? Both social exclusion (Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005) and stigma (Inzlicht, McKay, & Aronson, 2006) have been shown to be ego depleting, a process whereby “exerting self-control on one task drains the capacity for self-control and impairs performance on subsequent tasks requiring this same resource” (Inzlicht et al., 2006). It has been hypothesized that stigmatized individuals use and deplete self-control in order to manage their devalued social identity (Inzlicht et al., 2006), which requires a flexible use of emotion regulation strategies in the short term. Over time, however, the effort required may eventually diminish individuals’ resources and therefore their ability to understand and adaptively regulate their emotions, leaving them more vulnerable to depression and anxiety.

Emotion regulation involves a number of distinct processes (Gross, 2001), many of which may be salient for sexual minorities (Miller & Kaiser, 2001). Rumination is one specific emotion regulation response that may be especially likely to account for the association between stigma-related stress and internalizing disorders. Rumination is defined as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy in which an individual passively and repetitively focuses on his/her symptoms of distress and the circumstances surrounding these symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Rumination is a robust predictor of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008) as well as the onset and maintenance of depressive and anxiety disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000).

In addition to serving as a risk factor for depression and anxiety, rumination is also a consequence of general life stressors. A longitudinal study of adults found that participants who experienced greater chronic stress showed increased tendencies to ruminate and, in turn, increases in depressive symptoms over one year (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999). Similarly, in a recent prospective study of adolescents, rumination mediated the relationship between stressful life events and symptoms of depression and anxiety (McLaughlin & Hatzenbuehler, 2009). In addition to general life stress, specific stressors, such as childhood sexual abuse, lead to greater rumination (Conway, Mendelson, Giannopoulos, Csank, & Holm, 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2002).

Stigma-related stress is another specific stressor that may contribute to the development of rumination among sexual minorities, in part because chronic experiences of discrimination and rejection engender increased hypervigilance (Major & O’Brien, 2005; Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002), an element of rumination (Lyubomirsky, Tucker, Caldwell, & Berg, 1999). Additionally, several characteristics involved in managing a concealed identity like homosexuality could also serve to potentiate rumination. In particular, preoccupation with the stigma and whether it will be discovered is a common experience for those with concealed identities (Pachankis, 2008). Because preoccupation with the secret of a concealed stigma can be upsetting, individuals often attempt to suppress or inhibit thoughts about the stigma (Smart & Wegner, 1999), which can lead to subsequent rumination (King, Emmons, & Woodley, 1992). Facing constant decisions about when and whether to conceal the stigma also increases uncertainty and ambiguity in interpersonal interactions, which is associated with ruminative self-focus (Lyubomirsky et al., 1999). Finally, those with concealed identities engage in frequent self-monitoring (Pachankis, 2008). This increased focus on the self can, over time, develop into the passive and repetitive self-focus that characterizes much of rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991).

A recent longitudinal study with sexual minorities substantiates the hypothesis that stigma-related stress initiates rumination. The study included 74 bereaved gay male caregivers of loved ones who died from AIDS. Participants were assessed before the partner or close friend died and then at 1, 6, 13, and 18 months post-loss. Those who reported experiencing a specific stigma-related stressor (operationalized as perceived danger due to being gay) showed increased tendencies to ruminate and, in turn, increased depressive and anxious symptoms over time (Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in press). A strength of this study was its use of Hierarchical Linear Modeling, which enabled the estimation of a mediation model for each individual, using all available measurements at each time point. Although most studies of social stress focus on inter-individual differences in stress and subsequent mental health problems (Pearlin et al., 1981), this is the first study to demonstrate significant intra-individual variability in coping/emotion regulation processes (i.e., rumination) associated with changes in a specific stigma-related stressor (i.e., perceived danger).

A second longitudinal, community-based study also offers evidence for the psychological mediation framework. In this racially/ethnically diverse sample of over 1,000 adolescents, sexual minority youth experienced greater emotion dysregulation, a latent variable comprised of rumination (and emotional awareness). This increased emotion dysregulation accounted for the higher rates of depression and anxiety among the sexual minority youth, controlling for baseline symptom levels (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008).

The previous study only examined same-sex attraction; specific stigma-related stressors were not assessed. However, support for all three pathways of the psychological mediation framework comes from a recent experience sampling study with 31 LGB young adults, who completed measures on stigma-related stressors (e.g., discrimination experiences, sensitivity to rejection, and felt stigma), responses to these stressors, and mood over the course of ten days. Results indicated that rumination occurred more on days when stigma-related stressors were reported, and rumination mediated the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychological distress. In a follow-up experimental study, LGB participants who were induced to ruminate following the recall of an autobiographical discrimination event exhibited prolonged distress on both implicit and explicit measures relative to those who were induced to distract, providing support for a causal role of rumination in the stigma-distress relationship (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, in press).

Social/interpersonal processes

Social and interpersonal processes may also be important sequelae of stigma-related stress. Interpersonal theories of depression (Hammen & Rudolph, 1996) have indicated that stressors exert negative influences on mental health outcomes by interfering with interpersonal relations, suggesting that stigma-related stressors may also significantly alter social processes that in turn render sexual minorities more vulnerable to the development of internalizing psychopathology.

There is a large literature on the role of social support in buffering against the deleterious effects of stress on mental health (Cohen & Willis, 1985; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001), and research with sexual minorities has demonstrated the importance of parental/family (Goldfried & Goldfried, 2001), school (e.g., presence of Gay-Straight Alliances; Walls et al., 2008), and peer (Radkowsky & Siegel, 1997) support in protecting against adverse mental health outcomes. Although research has examined social support as a protective mechanism for sexual minorities, there has been less investigation of low social support as a possible consequence of exposure to stigma-related stress. Many individuals turn to others for support in times of stress (Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). Stigma-related stress, in contrast, could actually diminish social support among sexual minorities because it may lead them to isolate themselves from others in order to avoid future rejection (Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan, & Nuttbrock, 1997).

Several lines of evidence suggest that the experience of stigma and discrimination may cause social isolation. Experimental research has shown that the experience of social exclusion leads to selective memories for negative social information (Gardner, Pickett, & Brewer, 2000). As these memories for social rejection become more salient and therefore chronically available, research on construct accessibility (Higgins, King, & Mavin, 1982) suggests that they may become a source of avoidance of future interactions. In addition, people who are especially vigilant for signs of danger and rejection often communicate these expectations to others, ironically creating the very rejection they fear (Major & O’Brien, 2005). Finally, the decision to conceal one’s stigma may also lead to social avoidance and isolation (Pachankis, 2008). In an experience sampling study, those with concealable stigmas (e.g., gay and lesbian students, poor students) experienced a lift in mood and self-esteem only when in the presence of those who shared their stigma; however, they were significantly less likely to experience such occasions compared to those with visible stigmas (Frable, Platt, & Hoey, 1998). Fears of rejection and negative evaluation lead individuals with concealed stigmas to avoid entering close relationships for fear of others’ discovering their stigma (Pachankis, 2008). Although this avoidance enables them to escape rejection, research indicates that secret-keeping leads to more loneliness, introversion and social anxiety, compared to those who do not keep secrets (Kelly, 1998).

With few exceptions (e.g., Matthews et al., 2002), studies that have examined group differences in social support tend to reveal that sexual minorities have less social support than do heterosexuals, including less family connectedness and adult caring (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006) and lower satisfaction with social support networks (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). Controlling for social support (along with other general psychological processes) attenuated the association between sexual orientation and psychological distress, including depressive symptoms (Safren & Heimberg, 1999) and suicidality (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005). These studies did not assess specific stigma-related stressors in relation to social isolation; however, support for the psychological mediation framework comes from several investigations. For example, in a sample of over 900 Latino gay men, discrimination was associated with greater social isolation, which in turn led to greater psychological distress, including both depressive and anxiety symptoms (Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001). Another within-group study of sexual minority adolescents found that family support mediated the association between victimization experiences and psychological distress (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995).

Although these studies suggested a role for social support as a mediator of the stress-psychopathology association, they relied on cross-sectional data. A recent prospective study with bereaved gay men was able to address this methodological limitation and demonstrated that stigma-related stress (in the form of perceived danger) predicted less social support, which led to increases in depressive and anxious symptoms over 18 months (Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in press).

Similar results were obtained in an experience sampling study of 31 LGB young adults. Over the course of 10 days, LGB respondents reported more isolation and less social support subsequent to experiencing stigma-related stressors. Social isolation accounted for the prospective association between stigma-related stress and psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, in press).

Taken together, these findings suggest that variations in social context may cause intra-individual changes in social factors conferring risk for psychological problems. Thus, current evidence indicates that lack of social support contributes to the increased rates of internalizing symptoms among sexual minorities.

Cognitive processes

The cognitive processes affected by exposure to stigma-related stress are conceptualized as thought processes (both the content of thoughts as well as the process of thinking) that exacerbate, maintain, or prolong symptoms of depression and anxiety. According to cognitive theories, general life stressors may influence mental health through their impact on cognitive processes (e.g., Cole & Turner, 1993), suggesting that stigma-related stressors may also initiate changes in cognitions that in turn confer risk for internalizing psychopathology. Two related cognitive risk factors for internalizing disorders considered in this section are hopelessness (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989) and pessimism (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Carver & Scheier, 1998).

One cognitive mechanism that is likely to be a result of stigma-related stress is hopelessness, a risk factor for depression (Abramson et al., 1989). Hopelessness is defined as the belief that negative events will occur (or, conversely, that desired events will not occur) and that there is nothing the individual can do to change the situation (Abramson et al., 1989). According to the hopelessness theory of depression, individuals who exhibit this “negative inferential style” are more likely to experience depressive episodes, especially when they face stressful life events. Individuals exposed to chronic stressors in their environments, including a history of childhood maltreatment (Gibb, 2002) and emotional abuse from peers (Gibb, Abramson, & Alloy, 2004), appear to develop more negative cognitive styles, including hopelessness.

Given the association between life stress and vulnerability to negative cognitive styles, it is probable that the chronic nature of the stressors that sexual minorities confront engenders feelings of hopelessness. Indeed, the knowledge that prejudice and discrimination events are likely to continue to occur can, over time, convince individuals that there is nothing they can do to change their situation, which can lead to the development of depression. In within-group studies of sexual minorities, hopelessness is a significant predictor of suicidal behavior and ideation (van Heeringen & Vincke, 2000; Walls et al., 2008). Between-group comparisons indicate higher levels of hopelessness among LGB individuals compared to heterosexuals (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). When hopelessness is entered along with other general psychological processes in regression models, it has been shown to attenuate the association between sexual orientation and depressive symptoms (Safren & Heimberg, 1999) as well as suicidality (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005). In a nationally representative study of adolescents, there was a partial reduction in the relationship between same-sex attraction and suicidality when general psychological processes (including hopelessness) were statistically controlled (Russell & Joyner, 2001), providing partial support for mediation. No studies have examined hopelessness as a mediator of the relationship between specific stigma-related stressors (e.g., discrimination experiences) and internalizing symptoms, an important area for future research on the cognitive processes that are created by stigma-related stress.

Pessimism is a related cognitive risk factor for the development of internalizing disorders. Much of the research on the personality dimension of pessimism has focused on how pessimistic individuals exhibit negative expectations of future outcomes across a variety of life domains (Chang, 2001; Scheier & Carver, 1985). These expectations have important implications for how individuals cope with stressful life events, with pessimistic individuals typically withdrawing effort, leading to greater psychological distress over time (e.g., Carver, Pozo, Harris, Noriega, Scheier, & Robinson, 1993). The construct of pessimism is also central to the learned helplessness theory of depression, which posits that after experiencing events that are uncontrollable and aversive, individuals become helpless (Abramson et al., 1978). Pessimistic individuals typically make attributions for negative events that are internal (caused by the individual), global, and stable, and this pessimistic explanatory style has been shown to be a risk factor for depression following adversity and negative life events (Peterson & Seligman, 1984).

Recent research, building on this earlier work on pessimism, has suggested that individuals who are exposed to stressors based on their stigmatized identity may, over time, develop a pessimistic explanatory style. In particular, stigma-related stress that is recurrent can ultimately be viewed as stable, pervasive, and uncontrollable. For those individuals who also believe they are responsible for these experiences (i.e., make an internal attribution), a pessimistic explanatory style is likely to develop. A nationally representative study in the Netherlands found that, relative to heterosexual men, sexual minority men exhibited lower self-mastery—the belief that one has control over what occurs in his life (Sandfort, de Graaf, & Bijl, 2003)—a construct that is closely related to pessimism (Peterson & Seligman, 1984). In turn, this lower self-mastery explained lower quality of life among the sexual minority men (Sandfort et al., 2003). Pessimistic women experience more distress following prejudice-inspired events than optimistic women (Kaiser, Major, & McCoy, 2004). Although this study did not specifically address sexual orientation, it provides evidence for pessimism as a moderator, but not mediator, of the stigma-distress association. Support for mediation comes from a longitudinal study of (bereaved) gay men. Stigma-related stress led to greater pessimism, which in turn predicted internalizing symptoms over the 18 months of the study (Hatzenbuehler, Hilt, & Nolen-Hoeksema, in press).

A final cognitive variable that may also result from stigma-related stress is negative self-schemas. In the cognitive model of depression, depressed cognitions involve negative views of the self, the environment, and the future (Beck et al., 1979). Both cognitive and schema-focused therapies for depression have shown promise in altering these maladaptive cognitions regarding the self (Young, Rygh, Weinberger, & Beck, 2007). Chronic exposure to discrimination, rejection, and abuse can be expected to lead to negative self-schemas. Indeed, studies have shown that LGB individuals have lower self-esteem than heterosexuals (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Sandfort et al., 2003), and within-group studies of sexual minorities have revealed associations between low self-esteem and stigma-related stressors (e.g., Rosario et al., 1996). In turn, negative self-esteem is predictive of psychological distress, including suicidality (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003; van Heeringen & Vincke, 2000).

Support for negative self-schemas as mediators of the association between sexual orientation status and psychopathology is mixed, however. Although one between-group study showed that controlling for lower self-esteem (along with other general psychological processes) attenuated the relationship between sexual orientation and suicidality (Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005), another nationally representative study found that sexual orientation was still significantly associated with psychopathological outcomes after accounting for general psychological processes, including self-esteem (Wichstrom & Hegna, 2003). Within-group studies of sexual minorities have also produced mixed results regarding the extent to which negative self-esteem mediates the stress-psychopathology association. One study indicated that gay-related stress was still associated with psychological distress after accounting for self-esteem (Rosario et al., 1996), whereas two other studies have found reductions in the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychological distress (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995), as well as suicidality (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003), after controlling for self-esteem/self-acceptance. One possible methodological reason for these mixed results is that existing studies have typically entered self-esteem along with other psychological processes into regression models. Because the number and type of these psychological processes differ across studies, the relative influence of self-esteem on psychopathology also varies. Thus, the unique effects of self-esteem on psychopathological outcomes require further investigation.

Alcohol Use Disorders

Relative to research on depression and anxiety, there has been less research on psychosocial mediators of the effects of stigma-related stress on alcohol use. Nevertheless, existing research points to coping/emotion regulation, social/interpersonal, and cognitive processes through which stigma-related stress leads to the development of alcohol use disorders among LGB populations (see Table 2).

Coping and emotion regulation processes

Stress is a significant predictor of alcohol use (Dawson, Grant, & Ruan, 2005; Hasin, Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, Aharonovich, & Alderson, 2007) and associated problems (McCreary & Sadava, 1998; 2000). Stressful life events, including discrimination experiences (Bux Jr., 1996), are believed to challenge an individual’s coping resources, leading to the use of alcohol in an effort to regulate negative affect (e.g., Greeley & Oei, 1999). Coping motives—which refer to the “strategic use of alcohol to escape, avoid, or otherwise regulate negative emotions” (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995, p. 991)—are robust predictors of alcohol-related problems, including alcohol dependence (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998). Stress is associated with stronger coping motives for drinking, which in turn account for the relationship between stress and increased alcohol consumption (Ham & Hope, 2003; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004).

Taken together, this literature suggests that stigma-related stress may contribute to the development of coping motives for drinking. Indeed, discrimination is associated with negative affect (Diaz, et al., 2001; Herek et al., 1999; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 1995), and this increased negative affect may trigger motives to cope by drinking. In addition, positive expectancies about the effects of alcohol (e.g., that it will reduce tension) contribute to motives to cope by drinking (Cooper et al., 1995), and LGB young adults have greater positive alcohol expectancies than heterosexuals (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; Ziyadeh et al., 2007).

Thus, there is suggestive evidence from multiple lines of research that negative affect, drinking motives, and alcohol expectancies may serve mediating roles from discrimination to alcohol-related outcomes. To date, however, only one study has directly tested drinking to cope as a mediator of the relation between discrimination and drinking behaviors (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008b). In this study of over 2,300 young adults (with 109 LGB participants), discrimination among LGB respondents was significantly associated with negative affect as well as positive alcohol expectancies. These processes in turn led to coping motives, which contributed to greater alcohol-related problems, controlling for alcohol consumption.

Social/interpersonal processes

Several researchers have hypothesized that social processes, particularly social norms, may account for the higher rates of alcohol use disorders in LGB populations (Bux Jr., 1996; Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; McKirnan & Peterson, 1989). Social norms refer to the influence of the environment on an individual’s level of alcohol consumption and are predictors of alcohol use and associated problems among general samples of young adults (Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Sher, Bartholow, & Nanda, 2001) as well as in the U.S. adult population (Greenfield & Room, 1997). One nationally representative study of college students found that school-wide prevalence of substance use (i.e., social norms for use) did not predict the substance use behaviors of LGB students (Eisenberg & Wechsler, 2003). However, these norms were based almost exclusively on heterosexual students’ drinking habits, rather than the specific social norms for substance use within sexual minority social networks. In contrast, studies measuring social norms within sexual minority communities have tended to document that these norms are significantly predictive of substance use behaviors among LGB respondents (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a; Trocki et al., 2005).

Researchers have argued that sexual minorities may have more permissive social norms for the use of alcohol because bars were a place that the community often relied upon for interaction, due to a lack of comfort and safety in heterosexual establishments (Hefferman, 1998). In support of the hypothesis that stigma-related stress may contribute to higher social norms for drinking via engagement in a “bar culture,” one study found that discrimination experiences were associated with the use of bars as a primary social setting (McKirnan & Peterson, 1988), which in turn led to greater alcohol-related problems among sexual minority men (McKirnan & Peterson, 1989).

Evidence for a “bar culture” has not been entirely consistent (Bloomfield, 1993), however, and recent research suggests there may be age-cohort effects, in which younger sexual minorities are less reliant on bars for social venues (e.g., Crosby, Stall, Paul, & Barrett, 1998). Moreover, disparities in alcohol consumption appear to emerge in adolescence, long before a bar culture develops. One recent study with younger sexual minorities was able to address the role of social norms in drinking behaviors that did not occur in the context of a “bar culture.” During the transition from high school to freshman year of college, LGB individuals endorsed more permissive social norms among their social networks, which mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and increased alcohol use (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a). Future research is needed to establish whether specific stressors resulting from stigma may play a role in the development of more permissive social norms among sexual minorities.

Cognitive processes

Cognitive theories of alcohol use have suggested several important processes that may serve as explanations for increased alcohol use among at-risk drinkers. For example, a review of problem drinking in young adults identified several thought processes about drinking that confer risk for alcohol-related problems, including drinking motives and alcohol expectancies (Ham & Hope, 2003). According to alcohol expectancy theory (Goldman, Brown, & Christiansen, 1987), the combination of strong positive outcome expectancies (expectations of positive and negative reinforcement from drinking alcohol such as increased sociability and decreased tension) together with low negative expectancies (e.g., that alcohol will lead to cognitive or behavioral impairment) will lead to increased consumption and problems. A substantial literature documents the association between alcohol expectancies and drinking behavior (Jones et al., 2001).

A study of adult gay men showed that discrimination experiences predicted alcohol problems only among men whose cognitions (i.e., tension reduction expectancies) made them vulnerable to alcohol misuse (McKirnan & Peterson, 1988). Whereas this study examined moderation, a longitudinal study of LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers found that positive alcohol expectancies mediated the relationship between sexual orientation and alcohol use, both for men and women (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008a). Although this study suggests that expectancies may be one mechanism accounting for the stress-alcohol use association among sexual minorities, specific stigma-related stressors were not assessed. A nationally representative study of adolescents also found elevated alcohol expectancies among LGB youth relative to heterosexuals; however, controlling for alcohol expectancies (along with other general psychological processes) reduced the relation between sexual orientation and alcohol outcomes only for girls (Ziyadeh et al., 2007).

Discrimination experiences are associated with having greater positive alcohol expectancies in sexual minorities (Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2008b), which may be related to beliefs that alcohol can reduce the negative affect associated with stigma-related stressors. Future research should examine whether particular kinds of alcohol expectancies (e.g., tension reduction, “liquid courage,” negative self-perceptions) are especially likely to develop among those experiencing stigma-related stressors in order to provide a better understanding of how stigma-related stress might influence the development of higher alcohol expectancies among sexual minorities.

Summary and Discussion of Psychological Mediation Framework