Abstract

Phylogenetic relationships, species concepts and morphological evolution of the coprinoid mushroom genus Parasola were studied. A combined dataset of nuclear ribosomal ITS and LSU sequences was used to infer phylogenetic relationships of Parasola species and several outgroup taxa. Clades recovered in the phylogenetic analyses corresponded well to morphologically discernable species, although in the case of P. leiocephala, P. lilatincta and P. plicatilis amended concepts proved necessary. Parasola galericuliformis and P. hemerobia are shown to be synonymous with P. leiocephala and P. plicatilis, respectively. By mapping morphological characters on the phylogeny, it is shown that the emergence of deliquescent Parasola taxa was accompanied by the development of pleurocystidia, brachybasidia and a plicate pileus. Spore shape and the position of the germ pore on the spores showed definite evolutionary trends within the group: from ellipsoid the former becomes more voluminous and heart-shaped, the latter evolves from central to eccentric in taxa referred to as ‘crown’ Parasola species. The results are discussed and compared to other Coprinus s.l. and Psathyrella taxa. Homoplasy and phylogenetic significance of various morphological characters, as well as indels in ITS and LSU sequences, are also evaluated.

Keywords: Agaricales, Coprinus section Glabri, deliquescence, gap coding, morphological traits, Psathyrella, species concept

INTRODUCTION

Within Psathyrellaceae, the genus Parasola is considered a fairly homogeneous group of mushrooms, with a small umbrella-like pileus, which is deeply plicate (= grooved, Fig. 1f) up to the centre. Their fruiting bodies are completely devoid of veil (velum universale), hence the sectional name ‘Glabri’ was formerly applied to the group. They are common decomposers of different types of organic substrates (leaf-litter, wood, herbivore dung) and are distributed world-wide with most of the records being from Europe and North America, including scattered notes from Asia, Venezuela, Australia, Lesser Antilles and Africa (Pegler 1966, 1983, 1986, Dennis 1970, Grgurinovic 1997).

Fig. 1.

Examples of different species of Parasola. a. P. conopilus; b, c. P. auricoma, young and mature fruitbodies; d. fruitbody of P. misera, the only obligate coprophilous taxon. e. P. leiocephala; f. mature fruitbody of P. lilatincta showing typical plicate pileus surface; g. young fruitbody of P. lilatincta with conspicuous lilaceous coloration. — Photos by: a–f. L.G. Nagy; g. Derek Schafer.

Much attention was paid to species delimitation within the group (Orton & Watling 1979, Uljé & Bas 1988, Uljé & Bender 1997, Roux 2006). However, problems pertaining to species identification still exists which can either be attributed to the excessive morphological variability of taxa or to incorrect circumscription of some species (Nagy 2005). Characters used to delimit species include colour and size of fruitbodies, shape and size of spores, pleuro- and cheilocystidia, position of the germ-pore on the spores, and habitat. For instance, according to the most recent treatment of the group (Uljé 2005), P. kuehneri is defined as having smaller spores, a more reddish pileus and more cylindrical cheilocystidia than the closely related P. leiocephala. An important role was attributed to the angle of the germ pore with regard to the longitudinal axis of the spores. In Psathyrella conopilus and P. auricoma the germ pore is central (i.e. this angle is c. 90°) whereas in other taxa it is eccentric (< 90°). Parasola megasperma and P. plicatilis can have transitional states as well. Parasola lilatincta is considered the only species with lilaceous colours, caused by the presence of a pigment in tissues (Uljé & Bender 1997). It was suggested that these characters do not always co-occur and that therefore the presence of lilaceous tints is not diagnostic for P. lilatincta (Nagy 2005).

Recent phylogenetic studies drew attention to the contradictory phylogenetic position of Psathyrella conopilus. This taxon recurrently appeared in a sister position to other Parasola taxa (Walther et al. 2005, Larsson & Örstadius 2008, Padamsee et al. 2008, Vasutová et al. 2008). Possible support for this rather unexpected relationship of a non-deliquescent species with coprinoid fungi is, as suggested by Walther et al. 2005, provided by the presence of brown setae on the pileus of both Psathyrella conopilus and P. auricoma. However, this suggestion should be tested as in none of the foregoing studies did these two species cluster together. Summarising phylogenies published to date, Larsson & Örstadius (2008) introduced the name Parasola conopilus. Inconsistent with this is the opinion of Padamsee et al. 2008: they stressed the need for a separate genus that would accommodate P. conopilus. However, their morphological arguments for a new genus are incorrect (as noted also by Larsson & Örstadius 2008), because P. conopilus has no thin-walled pileocystidia at all, but thick-walled hairs, equal to those of P. auricoma. The possible relationship of P. conopilus to P. auricoma raises fundamental questions about the new classification of psathyrelloid and coprinoid fungi, i.e. how Psathyrella and its allies can be taxonomically separated from the phylogenetically related Coprinus-like genera (Redhead et al. 2001, Padamsee et al. 2008).

Within Parasola, the placement of P. auricoma is also controversial: it was often segregated in subsect. Auricomi from the rest of the group (subsect. Glabri) (Uljé & Bas 1988, Uljé & Bender 1997), while admitting its affinity to these taxa by being classified in sect. Pseudocoprinus (together with taxa of subsect. Setulosi, e.g. Coprinellus disseminatus). Phylogenetic studies published so far agree that P. auricoma is a member of the Parasola clade (Hopple & Vilgalys 1999, Moncalvo et al. 2002, Walther et al. 2005, Padamsee et al. 2008), but its position within that group is still obscure due to limited sampling of Parasola taxa.

Studies on fungal trait evolution mainly concentrated on features that are conserved at the family-phylum level (Lutzoni et al. 2001, Hibbett & Donoghue 2001, Hibbett 2004, Aanen & Eggleton 2005). Hence, very little is known about the phylogenetic value of morphological characters at or below genus level. However, before extrapolating phylogenetic results to classification, we think it is essential to know how morphological traits evolve. Upholding classification, comparative phylogenetic methods may facilitate selection of morphological features that are less homoplasious or show definite trends. Within dark-spored agarics, Frøslev et al. 2007 reported extensive conservation of distribution of certain chemical characters at species or group level in callochroid taxa of the genus Cortinarius. Padamsee et al. 2008 mapped a series of morphological features on the phylogeny (e.g., cystidial wall, presence of brachybasidia or pleurocystidia) of coprinoid fungi, but found most of them strongly homoplasious, which suggests characters in this group should be mapped on a smaller scale to get more reliable estimates of the nature of these traits.

In this study we address generic limits of Parasola based on a broad sampling of nrLSU and ITS sequences. Data from the two genes (nrLSU and ITS) and indel characters of 38 Parasola specimens, representing all but one morphologically distinct species, are combined in order to investigate species limits and intrageneric relationships. Specimens identified as P. galericuliformis and P. hemerobia were also included. Special attention is paid to the limits of P. lilatincta as compared to P. leiocephala and P. schroeteri, in order to ascertain the diagnostic utility of lilaceous coloration and spore size. Homoplasy and the extent of conservation exhibited by the morphological characters used to delineate species are estimated by mapping them onto the phylogeny of Parasola taxa. A resulting hypothesis of evolution of morphological traits in Parasola is presented and discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Taxon sampling

Specimens for this study were either field-collected or loaned from public herbaria. Identifications were based on type studies and two revisions (Uljé & Bas 1988, Uljé & Bender 1997) supplemented with experiences of a revision of > 500 herbarium specimens of all Parasola taxa by L.N. Freshly collected fruitbodies were dried in Silica gel to prevent tissues from collapsing. Collections within one species were chosen preferably from diverse geographical regions to reflect potential intraspecific differences.

In order to infer species limits, it was intended to sample at least three independent specimens from each morphological species of Parasola recognised by us during morphological studies (Nagy et al. unpubl.); thus we sampled 38 collections of the following 11 taxa: Parasola auricoma, P. galericuliformis, P. hemerobia, P. hercules, P. kuehneri, P. leiocephala, P. lilatincta, P. megasperma, P. misera, P. plicatilis and P. schroeteri (Table 1). Other taxa combined in Parasola were ignored in this study either because they are widely accepted synonyms of other taxa we included (P. nudiceps) or are considered dubious or insufficiently known (Uljé & Bas 1988, Nagy et al. unpubl.). The only well-characterised species for which we did not generate sequence data is P. setulosa, as this taxon is known only from the type specimen from the 1870s. GenBank sequences were not included in the LSU dataset because species limits are not settled in this group, so misidentifications are likely; the more so because little is known about the specimens from which the sequences were generated. Three additional specimens of P. conopilus were sampled to assess the phylogenetic position of this species with regard to Parasola taxa. Sequences for further 15 taxa, representatives of Coprinellus, Coprinopsis and Psathyrella were generated in order to infer deep branchings of Psathyrellaceae.

Table 1.

Origin, herbarium number, and GenBank accession numbers of specimens used in this study.

| Species | Locality | Voucher No. | Identifier | GenBank No. |

|

| LSU | ITS | ||||

| Coprinellus impatiens | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-1164 | L. Nagy | FM160732 | FM163177 |

| Coprinellus heptemerus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2144 | L. Nagy | FM160731 | FM163178 |

| Coprinopsis lagopus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2143 | L. Nagy | FM160730 | FM163179 |

| Coprinopsis narcotica | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2342 | L. Nagy | FM160729 | FM163180 |

| Coprinopsis pseudoniveus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2340 | L. Nagy | FM160728 | FM163181 |

| ‘Coprinus’ poliomallus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2336 | L. Nagy | FM160727 | FM163182 |

| ‘Coprinus’ bellulus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2341 | L. Nagy | FM160680 | FM163176 |

| Lacrymaria lacrymabunda | Sweden, Stockholm | SZMC-NL-0082 | L. Nagy | FM160726 | FM163183 |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-2140 | L. Nagy | FM160725 | FM163184 | |

| Parasola auricoma | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0087 | L. Nagy | FM160724 | FM163185 |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0268 | L. Nagy | FM160723 | FM163187 | |

| Parasola conopilus | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0465 | L. Nagy | FM160686 | FM163223 |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0286 | L. Nagy | FM160685 | FM163224 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0285 | L. Nagy | FM160684 | FM163225 | |

| Parasola galericuliformis | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-6601 | L. Nagy | FM160722 | FM163187 |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0095 | L. Nagy | FM160721 | FM163188 | |

| Parasola hemerobia | Hungary, Északi Középhegység | SZMC-NL-0284 | L. Nagy | FM160720 | FM163189 |

| Parasola hercules | Netherlands, Rijswijk | Uljé 1269 (L) | C.B. Uljé | FM160719 | FM163190 |

| Parasola kuehneri | Netherlands, Alphen aan den Rijn | Uljé 904 (L) | C.B. Uljé | FM160718 | FM163191 |

| Parasola leiocephala | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0466 | L. Nagy | FM160717 | FM163192 |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0288 | L. Nagy | FM160716 | FM163193 | |

| Germany, Tübingen | SZMC-NL-0283 | L. Nagy | FM160715 | FM163194 | |

| Parasola lilatincta | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0660 | L. Nagy | FM160714 | FM163195 |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0296 | L. Nagy | FM160713 | FM163196 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0281 | L. Nagy | FM160712 | FM163197 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0667 | L. Nagy | FM160711 | FM163199 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0472 | L. Nagy | FM160710 | FM163199 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0468a | L. Nagy | FM160709 | FM163200 | |

| England, Perthshire | D. Schafer 2382004 | L. Nagy | FM160708 | FM163201 | |

| Netherlands, Leiden | Arnolds 6939 (L) | C.B. Uljé | FM160707 | FM163202 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0683 | L. Nagy | FM160706 | FM163203 | |

| Parasola aff. lilatincta | Hungary, Északi Középhegység | SZMC-NL-0086 | L. Nagy | FM160705 | FM163204 |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0096 | L. Nagy | FM160704 | FM163205 | |

| Parasola megasperma | Denmark, Jutland | C 19683 (C) | L. Nagy | FM160703 | FM163206 |

| Spain, Gurmá Zuzones | AH 13089 | L. Nagy | FM160702 | FM163207 | |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-1924 | L. Nagy | FM160701 | FM163208 | |

| Parasola misera | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0490 | L. Nagy | FM160700 | FM163209 |

| Hungary, Északi Középhegység | SZMC-NL-0280 | L. Nagy | FM160699 | FM163210 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0677 | L. Nagy | FM160698 | FM163211 | |

| Parasola plicatilis | Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0477 | L. Nagy | FM160697 | FM163212 |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0075a | L. Nagy | FM160696 | FM163213 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0075 | L. Nagy | FM160695 | FM163214 | |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0097 | L. Nagy | FM160694 | FM163215 | |

| Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-0295 | L. Nagy | FM160693 | FM163216 | |

| Parasola schroeteri | Denmark, Arslev | Klamer 061998 (C) | L. Nagy | FM160692 | FM163217 |

| Sweden, Öland | SZMC-NL-0287 | L. Nagy | FM160691 | FM163218 | |

| Netherlands, Hilversum | Briër 1051999 (L) | C.B. Uljé | FM160690 | FM163219 | |

| Psathyrella ammophila | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2151 | L. Nagy | FM160689 | FM163220 |

| Psathyrella bipellis | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2535 | L. Nagy | FM160688 | FM163221 |

| Psathyrella prona var. utriformis | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-2534 | L. Nagy | FM160687 | FM163222 |

| Psathyrella leucotephra | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-1953 | L. Nagy | FM160683 | FM163226 |

| Psathyrella magnispora | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-1954 | L. Nagy | FM160682 | FM163227 |

| Psathyrella phaseolispora | Hungary, Alföld | SZMC-NL-1952 | L. Nagy | FM160681 | FM163228 |

1Herbarium of Szeged Microbiological Collection.

To root all coprinoid taxa, we used LSU and ITS sequences of Mythicomyces corneipes as well as three taxa of Agaricaceae which formerly appeared suitable outgroups for the Psathyrellaceae (Moncalvo et al. 2002, Matheny et al. 2006, Padamsee et al. 2008).

Laboratory protocols

DNA extraction was performed according to a modified CTAB extraction method (Hughes et al. 1999). In cases when this technique did not work well, we used the QIAGEN DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In many cases, a brown pigment (putatively that of the spores) appeared in the final extract which seemed to interfere with the PCR reaction. To remove this pigment, the DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Fermentas) was applied; this allowed removal of the majority of this stain and arbitrary enhancement of DNA concentration. Subsequent dilution of templates before PCR reactions was chosen so as to optimise yield of the desired fragment.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was used to amplify ITS and LSU regions of the nuclear ribosomal DNA repeat, employing the following primers: ITS1, ITS1F, ITS4, ITS4B for the ITS region and ITS1F, LR7, LR5, 5.8SR and LROR for the first 1.5 kb of the LSU gene (Gardes & Bruns 1993, http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm). PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 20 μL, following the protocol outlined in White et al. 1990 for both genes. For sequencing we used the same primers as described above for the ITS fragments and LR3R, LR16 or LR22 as additional sequencing primers in case of the LSU fragments (http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm). Cycle sequencing was performed by Macrogen Inc. (Korea). Sequences were assembled and edited in the programs Pregap v. 1.5 and Gap4 v.4.10 of the Staden Package (Staden et al. 1998). All sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table 1), and the alignment in TreeBASE (M4246).

Alignments and phylogenetic analyses

Assembled sequences were first aligned by ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) and inspected by eye. ITS alignments often showed high percentage of ambiguously aligned sites, which needed very time-consuming manual correction. To evade this problem we performed profile-to-profile alignments in MUSCLE (Edgar 2004), which gave improved alignments requiring much less manual correction. Profile-to-profile alignments were carried out on alignments computed with MUSCLE and edited manually. Before subjected to phylogenetic analyses, ambiguously aligned regions were excluded, non-overlapping start positions and ends of sequences were trimmed from the alignments. Gaps were coded in FastGap v. 1.0.8 (Borchsenius 2007) by means of the simple indel coding method of Simmons & Ochoterena (2000) in a separate, binary data partition.

Maximum Parsimony (MP), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian analyses of resulting alignments were performed to infer phylogenetic relationships of the group. Equally weighted MP searches were executed in PAUP v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003) according to the following strategy: initial heuristic searches were performed in 1 000 replicates to identify tree islands with saving a maximum of 5 trees per replicate (nchuck = 5, chuckscore = 1, TBR branch-swapping, MAXTREES set to autoincrease). Subsequent, more thorough branch swapping was conducted on the trees resulting from the search outlined above (start = current, nchuck = 0, chuckscore = 0). Gaps were treated as missing data. Nodal support was estimated by 1 000 bootstrap replicates with 10 random sequence additions per replicate. To assess the phylogenetic utility of gaps when coded as separate characters, a separate matrix containing only binary gap data was subjected to the same MP analyses as described above for the DNA matrix. Gaps were coded by means of the simple indel coding regime (Simmons & Ochoterena 2000) excluding leading and trailing gaps, with the expectation to provide more resolving power and nodal support (Simmons & Ochoterena 2000, Simmons et al. 2001, Kawakita et al. 2003). Rescaled Consistency Index (RCi) and Retention index (Ri) (Farris 1989) were calculated in PAUP for indel data in order to describe the homoplasy exhibited by this character type.

Best-fit substitution models used in the likelihood-based analyses were selected by the model testing algorithm implemented in Topali v. 2.19 (Milne et al. 2004). During model selection, results of the AICc criterion was considered, with sample size set to alignment size, as suggested by Posada & Buckley (2004).

ML estimation was performed in PhyML v. 2.4.4 (Guindon & Gascuel 2003) with 1 000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates. To discover tree space effectively, the program was run several times by using parsimony trees, recovered in the initial MP searches described above, as user-defined starting trees. Thus in case of the ITS+LSU dataset this number was 88 as the initial MP search recovered these trees. In all bootstrap analyses, values above 70 % were considered significant (Fig. 2).

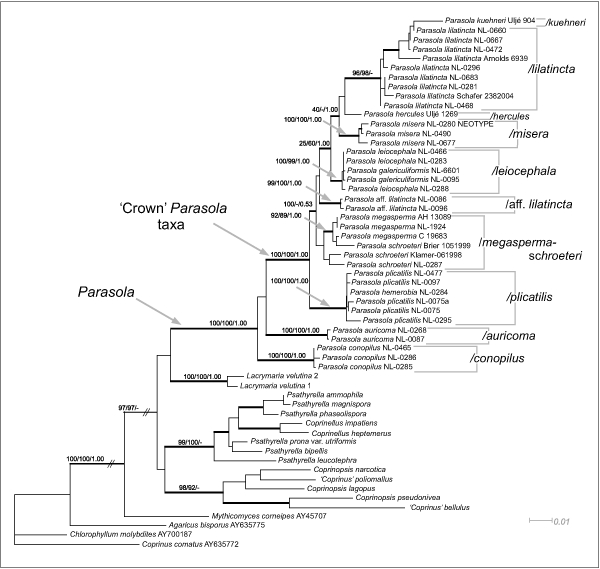

Fig. 2.

Maximum Likelihood (-lnL = 9989.930326) tree inferred from combined LSU+ITS dataset. Numbers above branches represent Maximum Likelihood, Maximum Parsimony bootstrap values and Bayesian Posterior Probabilities, respectively. Thickened branches receive strong support in at least one of the analyses (MP, ML or Bayesian). Two branches indicated by slanted parallel lines have been truncated for viewing.

Bayesian p(MC)3 analyses were run in MrBayes v. 3.1 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003). Metropolis Coupled Markov Chains with Monte Carlo simulation were run until likelihoods reached stationarity and the 2 independent runs converged (as deduced from the average standard deviation of split frequencies, i.e. < 0.01). Accordingly the chains were run three million generations in case of the ITS+LSU dataset, while the LSU+ITS+binary matrix required eight million generations (in this case burn-in was established in 5.5 × 106). By sampling every 100th generations from the 2 independent runs in MrBayes, the analyses resulted in 45 002 and 50 002 trees, respectively (after the first 25 % was discarded as burn-in for the ITS+LSU dataset and the first 5.5 × 106 generations for the LSU+ITS+binary matrix), which were used to construct 50 % majority rule consensus phylograms. The phylogeny inferred from the ITS+LSU+binary dataset is presented on Fig. 3. The Binary model implemented in MrBayes for restriction sites was used for the binary (gap) dataset with the command coding = variable to adjust for characters not included in this matrix, as suggested by Ronquist et al. 2005. Clades that received posterior probabilities > 0.95 were considered strongly supported.

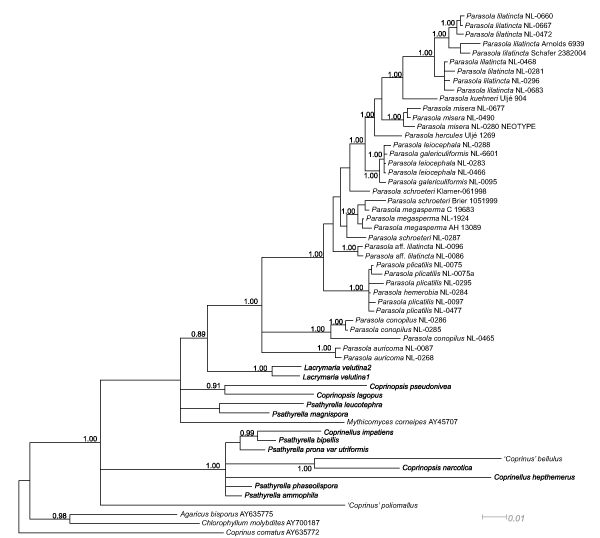

Fig. 3.

50% Majority Rule Bayesian phylogram inferred from the ITS+LSU+binary dataset. Trees used to compute the consensus were sampled for every 100th generations through 2.5 × 106 iterations in MrBayes. Significant posterior probability values are depicted on the branches. In the case of the Lacrymaria + Parasola clade, the posterior probability is presented on the branch although it is only moderately significant (0.89).

Character evolution

Various morphological characters were mapped onto the phylogeny of Parasola taxa under the parsimony principle. Parsimony mapping was performed in Mesquite v. 2.01 (Maddison & Maddison 2007) by using both the ML tree and the 50 % majority rule MP and Bayesian trees. The following traits were coded in a binary matrix and traced on the trees: veil (present/absent), fruitbody collapsing (Yes/No), pileus surface (smooth/plicate), thick-walled hairs on pileus (present/absent), pleurocystidia (present/absent), brachybasidia (present/absent), germ-pore (central/eccentric), spore shape (rounded triangular/ellipsoid), granules in tramal tissues (present/absent). Many studies treat Parasola as non-deliquescent (Redhead et al. 2001, Padamsee et al. 2008) while others claim that they show deliquescence to some extent (Orton & Watling 1979, Uljé & Bas 1988, Uljé 2005). By all means, Parasola taxa do differ from closely related psathyrelloid taxa (including P. conopilus) in that their fruitbodies rapidly lose turgor and collapse upon maturing. Hence, the process exhibited by Parasola taxa is interpreted here as an intermediate state between deliquescence and non-deliquescence and hereafter referred to as ‘collapsing’. Accordingly, we evaluated the phylogenetic utility of this character as well. The Rescaled Consistency index (RCi) and the Retention index (Ri) were calculated in PAUP v. 4.0b10 (Swofford 2003) for each character.

RESULTS

Sequence data, alignments and utility of gaps as characters in phylogenetic analyses

The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 regions and approximately the first 1 500 bp of the LSU gene were successfully sequenced for 38 specimens of the ingroup taxa. Old or extremely minute specimens often proved difficult to use for DNA extraction, accordingly, P. hercules and P. kuehneri are represented by one sequence each in the alignment. Additional 15 taxa from the genera Psathyrella, Coprinellus and Coprinopsis were sequenced for the ITS and LSU regions to serve as outgroups. To root Psathyrellaceae eight sequences of Agaricus bisporus, Chlorophyllum molybites, Coprinus comatus and Mythicomyces corneipes (AY635775, DQ404388, AY700187, DQ200928, AY635772, AY854066, AY745707, DQ404393, LSU followed by ITS in order of the taxa mentioned, respectively) were retrieved from GenBank. We used Agaricaceae as outgroup instead of choosing one of the genera within Psathyrellaceae because we were interested in the hitherto poorly understood deep branchings of the phylogeny as well (Hopple & Vilgalys 1999, Walther et al. 2005, Padamsee et al. 2008).

After exclusion of ambiguously aligned regions, the combined ITS+LSU dataset comprised 57 taxa and 2 114 characters of which 1 529 were constant, 155 were parsimony-uninformative and 430 sites were parsimony-informative. The ITS alignment contained large numbers of gaps, due to the high divergence of this region within Psathyrellaceae. By using more rigorously edited alignments of both LSU and ITS sequences, 397 binary coded gap characters were appended at the end of the combined matrix. Homoplasy of gap data in our case proved lower than in DNA sequence data: RCi gapmatrix : 0.6849 and Ri gapmatrix : 0.9006 vs RCi DNA : 0.3871 and Ri DNA : 0.7748.

Unfortunately, vast majority of gaps in the ITS and LSU alignments was confined to the connection of large clades (Coprinopsis, Coprinellus, Parasola and Psathyrella clades) and only few informative gaps reflected relationships within Parasola. The only exception is the pair P. conopilus – P. auricoma, which relationship was reflected in high degree by gap characters. For instance, at position 510 of the LSU alignment, there was an indel of a guanine (G), in the ITS alignment from position 667 to 681 there was a long gap unique to P. auricoma and P. conopilus, but lacking in all other Parasola taxa. Positions 82 (T), 126 (G), 188-9 (CA) and 297 (T) of the ITS alignment were represented by nucleotides in P. conopilus, while all other taxa of the alignment had gaps in these sites. The relationship of these two species to the rest of Parasola was also supported by gap characters.

Maximum parsimony analyses of gap data only, recovered congruent topologies as the combined ITS+LSU dataset, with 100 % bootstrap support for P. conopilus as sister group to all deliquescent (= collapsing) Parasola taxa (data not shown). In contradiction with this, Bayesian analysis of the ITS+LSU+gap dataset failed to recover this relationship with significant support (Fig. 3). Similarly, the Bayesian consensus tree of ITS+LSU data placed P. auricoma, P. conopilus and the ‘crown’ Parasola taxa in a tritomy. With regard to the topology within the genus Parasola, this tree (ITS+LSU) was congruent with those inferred from the ITS+LSU+gap dataset. Relationships of Coprinopsis and Coprinellus were better resolved when gap characters were neglected, probably due to alignment difficulties in these genera.

In our alignments, the large groups Coprinopsis, Coprinellus and Psathyrella clades were represented only by few taxa which – in some cases – hampered unambiguous interpretations of homology of certain indels during alignment. However, with denser sampling of taxa in these clades, this should be easier, thereby saving more characters to phylogeny inference.

Phylogenetic analyses

Model selection for likelihood-based analyses suggested the GTR+I+G and GTR+G as best-fit models for the LSU and the ITS datasets, respectively. The Maximum Likelihood tree is presented on Fig. 2. For Bayesian analyses all data (LSU+ITS+gap) were combined into a single file, resulting in a matrix of 2 511 characters. Convergence of runs in this case was difficult to get, only after 5.5 × 106 generations did the runs converge enough. Inclusion of gap characters did not influence the inferred branching order of Parasola specimens, only support values were increased to some extent. The 50 % Majority Rule Bayesian phylogram (Fig. 3) shows the same large clades as ML (Fig. 2) and MP (data not shown) trees. On this tree, however, the genus Coprinopsis was split into smaller clades, which may be attributed to the high divergence of ITS fragments of Coprinopsis, making the interpretation of positional homology often doubtful in our case (due to limited number of sequences).

All trees recovered provide evidence for the monophyly of Parasola including P. conopilus with strong support from all analyses (MLBS: 100 %, MPBS: 100 % BPP: 1.00). Clades corresponding to the genera Coprinopsis and Coprinellus were also recovered.

Within Parasola, individual clades for the following taxa received strong support: P. conopilus (MLBS: 100 %), P. auricoma (100 %), P. plicatilis (100 %), P. leiocephala (100 %), P. misera (100 %), P. lilatincta (96 %) and P. aff. lilatincta (99 %). Parasola hercules and P. kuehneri were represented in the analyses by a single sequence, so their monophyly cannot be addressed. Parasola conopilus was recovered as sister taxon of the clade containing all other Parasola taxa in MP and ML analyses with low bootstrap values (MP: 55 %, ML: 58 %), whereas Bayesian analysis groups P. conopilus with P. auricoma with no support (BPP: 0.66). In support of the ML and MP trees is the dataset comprised of gaps only (MPBS: 100 %).

The clade containing P. plicatilis specimens forms an early diverging lineage with regard to the rest of ‘crown’ Parasola taxa (excluding P. auricoma = subsect Glabri sensu Uljé 2005) on the ML and Bayesian trees (MLBS: 100 %, BPP: 1.00). Parasola hemerobia is nested in the P. plicatilis clade (MPBS: 100 %, MLBS: 100 %, BPP: 1.00) indicating that these species should be synonymised. This agrees well with results of morphological revisions (Uljé 2005, Nagy et al. unpubl.). Parasola plicatilis is characterised by lacking thick-walled hairs on the pileus, narrowly ovoid to almost ellipsoid spores measuring 10–13 μm in length. It colonises roadsides, lawns and other habitats rich in nutrients and is among the common species of Parasola, although it is far less common than was formerly supposed. Coprinus plicatilis was the name most commonly assigned to Parasola taxa, but vast majority of such specimens are misidentified (Nagy et al. unpubl.).

Parasola leiocephala includes P. galericuliformis, a species that should differ in having more subglobose spores (Orton & Watling 1979, Uljé & Bas 1988, Uljé 2005). Our morphological observations on the holotype of P. galericuliformis support this finding: it contains immature fruitbodies, so aberrant shape of spores is a consequence of incomplete ripening (Nagy et al. unpubl.). Parasola leiocephala is the most common species in the genus and is characterised by ovoid to rounded triangular spores, measuring 9–12 × 7–11 μm on average and the lack of granules in tramal tissues. It colonises various habitats, roadsides, lawns, but can be found on dung as well.

The clade containing P. schroeteri and P. megasperma is also remarkable. These species are characterised by large spores, medium-sized fruitbodies and occasional occurrence on dung. Parasola schroeteri is stated to differ from P. megasperma in having 12–15 μm long, rounded triangular (‘heart-shaped’) spores, whereas P. megasperma has larger (13–20 μm), ellipsoid spores (see Fig. 2).

Three taxa, P. lilatincta, P. misera and P. kuehneri, cluster together on a moderately supported (MPBS: 60 %, BPP: 0.85) clade in all analyses. Parasola misera is the smallest taxon in the genus (cap 3–15 mm broad), the only obligate coprophilous one, lacking pleurocystidia. According to the original description, P. lilatincta is characterised by having lilaceous colours on the pileus at least in young stages and cells that contain large amounts of oily, yellowish granules (‘pigment’) (Uljé & Bender 1997). However, our results clearly demonstrate that these characters are not linked to each other. Six of nine collections in the P. lilatincta clade lacked lilaceous coloration, but contained the oily granules mentioned in the original description. The position of P. kuehneri within this clade is unclear. On the ML tree (Fig. 2) it is nested in the P. lilatincta clade, but the relatively long branch it occupies implies some kind of error in the phylogenetic reconstruction. Consistent with this, Bayesian and MP analyses place this taxon outside the P. lilatincta clade with significant support.

Two specimens that were initially identified as P. lilatincta based on spore shape and the presence of (few) granules, were grouped together in a separate clade (MLBS: 99 %, MPBS: 100 %, BPP: 1.00), but their position is not well resolved. The LSU dataset strongly supports a sister position to the P. lilatincta clade (BPP: 1.00, results not shown). ITS sequences of these specimens contain a large number of unique characters which could be a reason of being placed in diverse (mainly basal) positions in various analyses. Unfortunately, no morphological differences were found between these two and other P. lilatincta specimens.

Evolution of morphological traits

Results from mapping morphological characters including extent of homoplasy are summarized in Table 2. Measures of homoplasy are calculated only for the Parasola clade (including P. conopilus) so as to exclude effects of outgroup taxa.

Table 2.

Summary of gains and losses of individual characters in the Parasola clade (Homoplasy measures are calculated only for Parasola taxa).

| Characters | Gains ML/MP/B 1 | Losses ML/MP/B | Rescaled Consistency Index | Retention Index |

| Veil | 0/0/0 | 1/1/1 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Hairs on pileus | 1/1/2 | 1/1/0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Spore shape | 1/1/1 | 3/3/3 | 0.1429 | 0.7143 |

| Pileus plicate | 1/1/2 | 0/0/0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Fruitbody collapsing | 1/1/2 | 0/0/0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Brachybasidia | 1/1/2 | 0/0/0 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Granules in cells | 2/2/2 | 0/0/0 | 0.2667 | 0.8000 |

| Germ pore | 1/1/1 | 2/2/2 | 0.1429 | 0.5714 |

| Pleurocystidia | 1/1/2 | 1/1/1 | 0.4000 | 0.8000 |

1ML = Maximum Likelihood, MP = Maximum Parsimony, B = Bayesian Posterior Probabilities.

Presence of veil, hairs on pileus, plicate pileus surface, presence of brachybasidia and the ability of fruitbodies to collapse showed no homoplasy within the Parasola clade, which indicates that these characters can be phylogenetically informative in Parasola and may be used for defining this genus in a phylogenetic context. Of these traits, presence of brachybasidia, pleurocystidia, spore shape and deliquescence were found strongly homoplasious on a much larger scale (Padamsee et al. 2008) in coprinoid fungi, with variable numbers of gains and reversals across different trees. Within Parasola, these traits were found highly informative.

On all trees, most parsimonious reconstructions of the presence or absence of veil imply a single loss before the Parasola clade, viz., on the branch leading to P. conopilus with no homoplasy (RCi: 1.0000). According to our results, thick-walled hairs evolved on the same branch where the veil was lost. Plicate pileus, presence of brachybasidia, pleurocystidia and the ability of fruitbodies to collapse evolved only once, on the branch leading to P. auricoma, showing no reversals in Parasola (RCi: 1.0000), except for the presence of pleurocystidia (RCi: 0.4000). Reconstruction on all trees is consistent in that rounded triangular shape of spores evolved in the ‘crown’ Parasola clades. In the P. plicatilis and P. megasperma/schroeteri clades this character is variable yielding relatively low RCi and Ri (0.1429 and 0.7143). Position of the germ pore correlates with spore shape, except that only two losses are assumed in P. megasperma due to the variable nature of this character within this taxon. Granulous content of the cells was reconstructed as having emerged two times; however, as mentioned above the position of the aff. lilatincta clade is dubious due to excessive variability in the ITS region (long branch attraction). If only LSU data are considered, it becomes a sister group of the P. lilatincta clade reducing the number of gains to 1 and the losses to 0. Pleurocystidia are absent in P. conopilus but are present in all other Parasola taxa except P. misera, so on the ML and MP trees one gain and one loss of this character is inferred.

DISCUSSION

Our study illustrates the potential of gap characters in non-coding DNA sequences to serve as phylogenetic characters. Although generally much fewer in number, they seem to provide more reliable estimates of the phylogeny as judged from measures of homoplasy and the number of parsimony informative sites. In our case, gaps of the ITS dataset turned out to be informative at the genus level with very low resolving power among species of Parasola. This is in concordance with former studies (Simmons & Ochoterena 2000, Simmons et al. 2001, Müller 2006, Egan & Crandall 2008) which emphasised the role of gap characters in family-genus level phylogenetic studies. Some cases were also reported where distribution of gaps is diagnostic for species, however (Kovács & Jakucs 2006). ITS alignments are often characterised by being intermitted by several gaps. Indel regions are treated by several authors as ‘ambiguously’ aligned regions and are excluded from phylogenetic analyses (Álvárez & Wendel 2003). However, the information they encode can and, in our opinion, should be incorporated in phylogenetic analyses with holding positional homology in view (Lutzoni et al. 2000). In this manner, more attention should be paid to the resolving power of ITS regions at the genus-family level when indels are integrated in phylogenetic analyses. From an analytical point of view, it is favourable to include gaps characters as a binary matrix in combined analyses, after testing for significant incongruence (which – to our knowledge – can be done at the moment only under the parsimony principle). Unfortunately, there are very few phylogeny softwares that can handle mixed data (e.g. MrBayes).

Our MP analyses of both the nucleotide and binary matrices as well as the ML tree resolve P. conopilus as an early diverging taxon of the Parasola clade, although uncertainty remains about this topology with respect to the support values and the contradicting topology of the Bayesian phylogram (Fig. 3). Former studies support the basal position of P. conopilus with significant support (Walther et al. 2005, Larsson & Örstadius 2008, Padamsee et al. 2008, Vasutová et al. 2008), so it seems likely that this relationship is correct. Analysis of more genes seems necessary to address the position of P. conopilus. Different classifications of P. conopilus have been proposed: either as a separate, monotypic genus (Padamsee et al. 2008) or as a member of Parasola (Larsson & Örstadius 2008). However, we think inclusion in Parasola is better justified so as to keep the number of new genera as low as possible. Results of the Bayesian analyses also entail a similar viewpoint, as on the Bayesian 50 % majority rule tree (Fig. 3). Parasola auricoma and P. conopilus clades form a tritomy with a clade containing all other Parasola taxa. Parasola auricoma and P. conopilus are morphologically united by the presence of thick-walled hairs on the pileus, warm brown colour of fruitbodies, and ellipsoid spores with central germ-pore.

Specimens identified by us as P. lilatincta based on spore shape and presence of granules in tissues, but neglecting lilaceous coloration, grouped together with strong support. This supports the assumption that lilaceous colour of fruitbodies is not linked to the presence of granules (Nagy 2005) and is of limited value in identification. Besides, it clarifies the situation often faced in collections labelled as P. cf. leiocephala or P. schroeteri: most specimens lacking lilac colour with larger spores and granules were assigned to these species, whereas now it is evident that the presence of granules and spore size are diagnostic enough to assign such collections to P. lilatincta.

Two specimens (NL-0096 and NL-0086) identified morphologically as P. lilatincta are clustered on a separate, strongly supported branch appearing in contradicting positions on the trees inferred, which could be attributed to long branch attraction. Oily granules are present in both specimens, in agreement with the (hereby) amended definition of P. lilatincta as well as spore shape and size, which are also similar. Although no morphological differences were found by us, considering the results of the phylogenetic analyses we label these ‘P. aff. lilatincta’, awaiting more specimens to see if they truly represent a unique lineage.

In the present study the taxonomic value of several morphological characters is amended. We found that spore characteristics, such as shape, size and the position of germ pore, are most useful for delimitation of taxa in Parasola. In certain taxa (P. plicatilis, P. megasperma), however, spore shape may vary from almost ellipsoid to rounded triangular. The issue of P. megasperma is further complicated by P. schroeteri, which phylogenetic analyses failed to separate unequivocally from P. megasperma. Of these two species, there are collections, indeed, which show transitional spore shape and size. However, the limitation of ITS to discriminate some species has also been observed in Boletus by Beugelsdijk et al. (2008). More material should be sequenced to clarify whether they should be synonymised or considered to be separate taxa. Other ‘crown’ Parasola taxa (P. hercules, P. kuehneri, P. leiocephala, P. lilatincta, P. misera) have rounded triangular spores, differences can be found in their sizes only. Of these, P. misera is remarkable in lacking pleurocystidia and being obligate coprophilous.

In the present study we evaluated the phylogenetic utility of several morphological characters. Our results revealed a number of characters which appear to be associated with the emergence of the parasoloid lineage: loss of veil (in P. conopilus), appearance of plicate pileus, pleurocystidia, brachybasidia and the ability of fruitbodies to collapse upon maturity (in P. auricoma). This group of characters could be considered diagnostic not only for the emergence of Parasola taxa, but we think also for other coprinoid lineages as well. In line with the loss of veil, thick-walled hairs evolved on the same branch. These two structures may stand for the same function, i.e. protecting the pileus from water droplets or insects. Another species, not included in the phylogenetic analyses, P. setulosa shares the thick-walled hairs with P. auricoma, but has broad, rounded triangular spores with central germ-pore. Hence this can be regarded as an intermediate between ‘crown’ Parasola taxa and P. auricoma. A next step might be P. plicatilis, in which thick-walled hairs are lost, but the spores are (narrowly) rounded triangular and the germ pore is eccentric (although often only slightly). The remainder of the taxa possess rounded triangular spores (except P. megasperma in which this trait is variable) equipped with an eccentric germ-pore and lack hairs on the pileus.

Granules in cells (pileipellis elements, cystidia, basidia) were considered unique to P. lilatincta. However, our phylogenetic analyses recovered another clade of morphologically very similar specimens which shares this character with P. lilatincta. We refer to this clade as P. aff. lilatincta. Hence, for the time being it cannot be concluded with certainty that this character (oily granules) evolved twice in the Parasola clade as suggested by the most parsimonious reconstructions.

The ability of fruitbodies to collapse showed one gain and no losses across Parasola regardless of the tree the character was traced over. In this respect our study should complement to the paper of Padamsee et al. 2008, who examined (among others) the evolution of deliquescence and recovered 3–6 gains across all coprinoid fungi. However, they explicitly treated Parasola as non-deliquescent. In the literature, there is no consensus as to whether Parasola is deliquescent or not. Some authors treat them non-deliquescent and maintain the genus Pseudocoprinus for these taxa (Kühner 1928, McKnight & Allison 1970), while others did not distinguish this way (e.g. Uljé 2005). The phenomenon observed in Parasola (excluding P. conopilus) might be interpreted as incomplete deliquescence, or an ability of the fruitbodies to collapse upon maturity, but anyway, it is markedly different from psathyrelloid taxa (e.g. P. conopilus). Moreover, this study illustrates that certain characters, like presence of veil, hairs on pileus, plicate pileus surface, presence of brachybasidia and pleurocystidia, found highly homoplastic by Padamsee et al. 2008 can be phylogenetically informative when mapped on a smaller scale.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the curators of the herbaria AH, C, L and Derek Schafer (UK) for the loan of specimens. G.M. Kovács is thanked for valuable suggestions on the manuscript. The Synthesys program of the European Union enabled the first author to study Parasola specimens collected by C.B. Uljé in Leiden. Staff members at the Department of Microbiology at the University of Szeged are thanked for their continuous help and fruitful discussions.

REFERENCES

- Aanen DK, Eggleton P. 2005. Fungus-growing termites originated in African rain forest. Current Biology 15: 851 – 855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvárez I, Wendel JF. 2003. Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 29: 414 – 434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk DCM, Linde S van der, Zuccarello GC, Bakker HC den, Draisma SGA, Noordeloos ME. 2008. A phylogenetic study of Boletus section Boletus in Europe. Persoonia 20: 1 – 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchsenius F. 2007. FastGap 1.0.8. Software distributed by the author (http://192.38.46.42/aubot/fb/FastGap_home.htm). [Google Scholar]

- Dennis RWG. 1970. Fungus flora of Venezuela and adjacent countries. Kew Bulletin Additional Series 3: i – xxxiv [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792 – 1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan AN, Crandall KA. 2008. Incorporating gaps as phylogenetic characters across eight DNA regions: Ramifications for North American Psoraleeae (Leguminosae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46: 532 – 546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris JS. 1989. The retention index and the rescaled consistency index. Cladistics 5: 417 – 419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frøslev TG, Jeppesen TS, Lassoe T, Kjoller R. 2007. Molecular phylogenetics and delimitation of species in Cortinarius section Calochroi (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) in Europe. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44: 217 – 227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardes M, Bruns TD. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Molecular Ecology 2: 113 – 118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grgurinovic CA. 1997. Larger fungi of Australia Botanic Garden of Adelaide, Australia: [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. PhyML – A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Systematic Biology 52: 696 – 704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS. 2004. Trends in morphological evolution in Homobasidiomycetes inferred using maximum likelihood: A comparison of binary and multistate approaches. Systematic Biology 53: 889 – 903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett DS, Donoghue MJ. 2001. Analysis of character correlations among wood decay mechanisms, mating systems, and substrate ranges in Homobasidiomycetes. Systematic Biology 50: 215 – 242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopple JS, Vilgalys R. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships in the mushroom genus Coprinus and dark spored allies based on the sequence data from the nuclear gene coding for the large ribosomal ubunit RNA: divergent domains, outgroups, and monophyly. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 13: 1 – 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes KW, McGhee LL, Methven AS, Johnson JE, Petersen RH. 1999. Patterns of geographic speciation in the genus Flammulina based on sequences of the ribosomal ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 area. Mycologia 91: 978 – 986 [Google Scholar]

- Kawakita A, Sota T, Ascher JS, Ito M, Tanaka H, Kato M. 2003. Evolution and phylogenetic utility of alignment gaps within intron sequences of three nuclear genes in bumble bees (Bombus). Molecular Biology and Evolution 20: 87 – 92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács GM, Jakucs E. 2006. Morphological and molecular comparison of white truffle ectomycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 16: 567 – 574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühner R. 1928. Le dévéloppement et la position taxonomique de l’Agaricus disseminatus Pers. Le Botaniste 20: 147 – 195 [Google Scholar]

- Larsson E, Örstadius L. 2008. Fourteen coprophilous species of Psathyrella identified in the Nordic countries using morphology and nuclear rDNA sequence data. Mycological Research 112: 1165 – 1185 doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F, Pagel M, Reeb V. 2001. Major fungal lineages are derived from lichen symbiotic ancestors. Nature 411: 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F, Wagner P, Reeb V, Zoller S. 2000. Integrating ambiguously aligned regions of DNA sequences in phylogenetic analyses without violating positional homology. Systematic Biology 49: 628 – 651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WR, Maddison DR. 2007. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.01 http://mesquiteproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Matheny PB, Curtis JC, Hofstetter V, Aime MC, Moncalvo JM, Ge ZW, Yang ZL, Slot JC, Ammirati JF, Baroni TJ, Bougher NL, Hughes KW, Lodge DJ, Kerrigan RW, Seidl MT, Aanen DK, DeNitis M, Danielle G, Desjardin DE, Kropp BR, Norvell LL, Parker A, Vellinga EC, Vilgalys R, Hibbett DS. 2006. Major clades of Agaricales: a multi-locus phylogenetic overview. Mycologia 98: 982 – 995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight KH, Allison P. 1970. Two new species of Pseudocoprinus. Morris Arboretum Bulletin 20: 75 [Google Scholar]

- Milne I, Wright F, Rowe G, Marshal DF, Husmeier D, McGuire G. 2004. TOPALi: Software for automatic identification of recombinant sequences within DNA multiple alignments. Bioinformatics 20: 1806 – 1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncalvo JM, Vilgalys R, Redhead SA, Johnson JE, James TY, Aime MC, Hofstetter V, Verduin SJW, Larsson E, Baroni TJ, Thorn RG, Jacobsson S, Clémencon H, Miller OK. 2002. One hundred and seventeen clades of euagarics. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23: 357 – 400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K. 2006. Incorporating information from length-mutational events into phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38: 667 – 676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L. 2005. Additions to the Hungarian mycobiota I: Coprinus. Clusiana 46: 65 – 90 [Google Scholar]

- Orton PD, Watling R. 1979. Coprinaceae Part 1: Coprinus. British Fungus Flora. Agarics and Boleti: Part 2 Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, UK: [Google Scholar]

- Padamsee M, Matheny BP, Dentinger BTM, McLaughlin DJ. 2008. The mushroom family Psathyrellaceae: Evidence for large-scale polyphyly of the genus Psathyrella. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46: 415 – 429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegler DN. 1966. Tropical African Agaricales. Persoonia 4: 73 – 124 [Google Scholar]

- Pegler DN. 1983. Agaric flora of the Lesser Antilles. Kew Bulletin Additional Series 9: 1 – 668 [Google Scholar]

- Pegler DN. 1986. Agaric flora of Sri Lanka. Kew Bulletin Additional Series 12: 1 – 519 [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Buckley TR. 2004. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of the AIC and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Systematic Biology 53: 793 – 808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhead SA, Vilgalys R, Moncalvo JM, Johnson J, Hopple JS. 2001. Coprinus Persoon and the disposition of Coprinus species sensu lato. Taxon 50: 203 – 241 [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572 – 1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP, Mark P van der. 2005. MrBayes 3.1 Manual: 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Roux P. 2006. Mille et un champignon Ed. Roux Sainte-Sigolène.France: [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MP, Ochoterena H. 2000. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Systematic Biology 49: 369 – 381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MP, Ochoterena H, Carr T. 2001. Incorporation, relative homoplasy, and effect of gap characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Systematic Biology 50: 454 – 462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staden R, Beal KF, Bonfield JK. 1998. The Staden package. Methods in Molecular Biology 132: 115 – 130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. 2003. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and other methods), Version 4 Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research 22: 4673 – 4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uljé CB. 2005. Coprinus . In: Noordeloos ME, Kuyper TW, Vellinga EC. (eds), Flora agaricina neerlandica 6: 22 – 109 CRC press, Boca Raton, Fl, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Uljé CB, Bas C. 1988. Studies in Coprinus I: Subsections Auricomi and Glabri of Coprinus section Pseudocoprinus. Persoonia 13: 433 – 448 [Google Scholar]

- Uljé CB, Bender H. 1997. Additional studies in Coprinus subsection Glabri. Persoonia 16: 373 – 381 [Google Scholar]

- Vašutová M, Antonín V, Urban A. 2008. Phylogenetic studies in Psathyrella focusing on sections Pennatae and Spadiceae – new evidence for the paraphyly of the genus. Mycological Research 112: 1153 – 1164 doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther G, Garnica S, Weiß M. 2005. The systematic relevance of conidiogenesis modes in the gilled Agaricales. Mycological Research 109: 525 – 544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. 1990. Amplication and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics . In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. (eds), PCR Protocols: a guide to methods and applications: 315–322 Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA: [Google Scholar]