Abstract

PAX3-FKHR is a fusion oncoprotein generated by the 2;13 chromosomal translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS), a cancer associated with the skeletal muscle lineage. Previous studies determined that high-level PAX3-FKHR expression is a consistent feature in ARMS tumors. To investigate the relationship between expression and phenotype in human myogenic cells, PAX3-FKHR was introduced into immortalized human myoblasts to produce a low overall PAX3-FKHR expression level. Although PAX3-FKHR alone failed to exert transforming activity, a combination of PAX3-FKHR and MYCN induced transforming activity in cell culture assays. Furthermore, myoblasts expressing PAX3-FKHR with or without MYCN formed tumors in SCID mice. These tumors demonstrated invasive features and expressed myogenic markers, consistent with rhabdomyosarcoma. Comparisons of tumor and parental cells revealed that only a subset of parental cells developed into tumors and that tumor cells expressed high PAX3-FKHR levels compared with transduced parental cells. Subcloning of parental PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-transduced myoblasts identified rare high PAX3-FKHR-expressing subclones with high transforming and tumorigenic activity; however, most subclones expressed low PAX3-FKHR and showed neither transforming nor tumorigenic activity. Finally, RNA interference experiments in myoblast-derived tumor and ARMS cells revealed that high PAX3-FKHR expression plays a crucial role in regulating proliferation, transformation, and differentiation. These findings support the premise that high PAX3-FKHR-expressing cells are selected during tumorigenesis.

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is an aggressive pediatric soft tissue sarcoma associated with the skeletal muscle lineage. The most common cytogenetic feature of this cancer is a chromosomal translocation, t(2;13)(q35;q14), which generates a fusion between the PAX3 and FKHR (FOXO1) genes.1 In addition, a PAX7-FKHR fusion gene is generated by a variant translocation, t(1;13)(p36;q14), which occurs in a smaller subset of cases. The PAX3- or PAX7-FKHR fusion genes encode proteins, which contain the intact PAX3 or PAX7 DNA binding domain fused with the FKHR transcriptional activation domain. These fusion proteins have greater transcriptional activity than wild-type PAX3 or PAX7 and function as aberrant transcription factors, which deregulate downstream target genes2,3 to contribute to tumorigenesis.

A striking feature of the 2;13 translocation is the overexpression of PAX3-FKHR relative to wild-type PAX3, at both the RNA and protein levels.4 In a small subset of cases, the PAX3-FKHR fusion gene is amplified and the basis for overexpression is copy number-dependent. However, in the majority of cases, there are comparable numbers of PAX3-FKHR and PAX3 gene copies, and the basis for overexpression seems to be a copy number-independent increase in transcriptional rate. The consistent finding of high PAX3-FKHR expression in ARMS tumors suggests that the high fusion product level is needed to surpass a critical threshold for oncogenic activity. Of note, PAX7-FKHR is also consistently overexpressed in ARMS tumors with the 1;13 translocation although the underlying mechanism is usually gene amplification.4

Several phenotypic activities are attributed to the PAX3-FKHR protein. Oncogenic activity was demonstrated in chicken embryo and murine fibroblasts in the soft agar colony assay.5,6 However, our previous studies indicated that transformation of NIH3T3 fibroblasts is only optimal at low PAX3-FKHR levels.7 In contrast, at high PAX3-FKHR levels, comparable with the levels in human ARMS tumor cells, the predominant effect in several immortalized murine lines is growth suppression and/or cell death. Based on the ability of human ARMS cells to tolerate these high PAX3-FKHR levels, we hypothesize that additional collaborating alterations occur during ARMS tumorigenesis and permit these cells to tolerate high fusion protein expression.

In this report, we now move our studies of PAX3-FKHR into a human myoblast system. Based on the association of ARMS with the skeletal muscle lineage and the frequent occurrence of ARMS in skeletal muscle, the human myoblast is postulated to be a potential cell of origin and an important cell type for investigating PAX3-FKHR action. For these reasons, we selected a human myoblast line that is immortalized with BMI1 and TERT.8 BMI1 functions as a transcriptional repressor of the CDKN2A locus, and down-regulates both p16INK4a and p14ARF expression,9 thereby disrupting the Rb and p53 pathways. These pathways are often inactivated by a variety of mechanisms in ARMS tumors.10 TERT encodes the catalytic telomerase subunit and is required during immortalization to prevent senescence.11 In this human myoblast system, we investigate the role of PAX3-FKHR and oncogenic cofactors in regulating the phenotypic activities of proliferation, transformation, differentiation, and tumorigenicity. Furthermore, we evaluate the significance of PAX3-FKHR expression levels in these regulatory activities. Our findings highlight the importance of high PAX3-FKHR expression in ARMS oncogenesis and provide further evidence for a collaborating event associated with high PAX3-FKHR expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Growth Assay, and Retroviral Transduction

A human DMD myoblast cell line, immortalized by transduction with TERT and BMI1, was obtained from Dr. D. Trono (University of Geneva).8 This line was cultured in F10 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) with 15% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Gibco), 1 mmol/L creatine, 100 ng/ml pyruvate, and 50 μg/ml uridine. For growth curves, 5 × 104 cells/well were seeded in six-well plates, and the cell number was counted every other day using the trypan blue exclusion method. To isolate subclones, myoblasts were diluted to 0.3 cell/well in 96-well plates, transferred to 12-well plates after 2 weeks, and then further expanded.

The retroviral transduction protocol and retroviral constructs were described previously.7,12 A pBabe-based retroviral construct was used to deliver PAX3-FKHR with puromycin selection (0.8 μg/ml) and a pK-hyg-based construct was used to deliver MYCN with hygromycin selection (120 μg/ml). The transduction efficiencies for these two constructs are ∼15 and ∼45%, respectively. A minidystrophin gene in a lentiviral vector was provided by Dr. J. Chamberlain (University of Washington).13 To target the PAX3-FKHR fusion point, a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) construct was designed with a 29-bp sequence (shown as underlined) corresponding to the PAX3-FKHR fusion point (5′-GATCCGCCTCTCACCTCAGAATTCAATTCGTCATTTCAAGAGAATGACGAATTGAATTCTGAGG TGAGAGGCTTTTTACGCGTG-3′). This shRNA construct was cloned into the retroviral vector pSIREN-RetroQ-ZsGreen (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and transduced into cells based on our previously published protocol using FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and 293T cells.7,12

Expression Assays

Cell lysates were prepared as described,7 and nuclear extracts were prepared using nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For Western blots, cell lysates (40 μg) or nuclear extracts (20 μg) were fractionated on 4 to 12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies included anti-PAX3 rabbit polyclonal and anti-myosin heavy chain monoclonal (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-MYCN rabbit polyclonal, anti-myogenin monoclonal, anti-ARF goat polyclonal, anti-Bmi1 rabbit polyclonal, anti-p16 rabbit polyclonal, anti-actin goat polyclonal, anti-dystrophin monoclonal, and anti-histone H1 rabbit polyclonal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

RNA was extracted from frozen tumors using RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). RNA was screened for PAX3-FKHR expression using reagents from a previously described quantitative (q) RT-PCR assay.14 For quantitation, a standard curve was prepared with RNA from the Rh30 ARMS cell line. The qRT-PCR assays were run on 384-well plates in the ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System. To normalize for RNA content, the control gene 18S RNA was assayed in separate wells of the same run using a premade qRT-PCR assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Transformation Assays

For the soft agar colony assay, 105 cells in 0.35% agar (Agar Noble, Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) were seeded on top of 0.7% agar and then monitored, as described previously.12 For the focus formation assay, 103 cells were mixed with 106 NIH3T3 cells, seeded into a 10-cm dish and then monitored, as described previously.12 Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 12, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Establishing Xenograft Tumor Model in SCID Mice

To evaluate tumorigenesis of transduced myoblasts, cells were injected into 4- to 5-week-old female mice (Fox Chase SCID Mice, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). For s.c. xenografts, 106 exponentially growing cells were harvested and washed with PBS, resuspended in 200 μl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and injected subcutaneously into the flank region. For i.m. xenografts, 5 × 105 cells were resuspended in 50 μl of PBS and injected intramuscularly into the rear thigh. Tumor size was measured three times per week, and when tumors reached 1.5 cm, animals were euthanized for tumor harvest and pathological analysis. All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. To culture tumor cells, harvested tumor was minced into small pieces and incubated for 30 minutes with collagenase/dispase (1 U/ml, Roche Applied Science) in F10 medium at 37°C with shaking. After centrifugation and washing to remove enzymes, the cells were cultured in medium with 15% fetal bovine serum.

Histopathology and Immunochemistry

Harvested tumors were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for histological studies. Four-micrometer tissue sections were stained with H&E and assessed histologically by a pathologist (B.R.P.). For immunohistochemical analysis, sections were cut at 4 μm onto charged glass slides. The slides were deparaffinized, and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% H2O2. Antigen retrieval (for myogenin) was performed by heating in a pressure cooker in antigen-unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunohistochemical staining was performed on a Dako Autostainer (Dako, Carpenteria, CA), using the M.O.M. immunodetection kit (Vector Laboratories). Primary mouse monoclonal antibodies were applied at the following dilutions: myogenin (Dako) at 1:50, desmin (Dako) at 1:20, MyoD1 (Dako) at 1:80, and muscle specific actin (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY) at 1:50 for 30 minutes at room temperature. Detection was done using the Vectastain Elite ABC standard kit (Vector Laboratories) and diaminobenzidine (Dako).

Southern Blotting Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from cultured cells and tumors using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). For Southern blot transfer, 5 μg of DNA was digested with BglII, fractionated by electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels, and transferred onto Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). For the labeling probe, a DNA fragment from the pBabe puromycin resistance gene was isolated by ClaI/HindII digestion, and a fragment from the pK-Hyg hygromycin resistance gene was isolated by NotI/SalI digestion. The purified DNA fragments were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Kit, Roche Applied Science), and hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

PAX3-FKHR Transforms Human Myoblasts in Culture in the Presence of MYCN

A human myoblast cell line (referred to as Dbt), which is derived from a Duchenne muscular dystrophy donor and immortalized by BMI1 and TERT,8 was used as the starting point for our studies of PAX3-FKHR action. To verify expression characteristics of this myoblast cell line, Western blotting analysis was performed to reveal BMI1 expression and absent ARF and p16 expression as a result of BMI1 action (data not shown). To explore the properties of PAX3-FKHR in these human myoblasts, this fusion product was introduced using the retroviral vector pBabe. Western blot analysis showed low-level PAX3-FKHR expression (Figure 1A), which is significantly less than expression in ARMS cell lines (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the inability of most cell types to tolerate high PAX3-FKHR expression without some event that attenuates growth suppression/cell death associated with high-level expression.

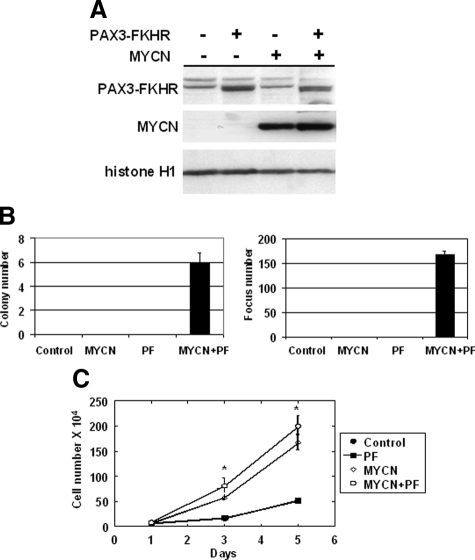

Figure 1.

Contributions of PAX3-FKHR and MYCN to transformation of immortalized human myoblasts in cell culture. A: Western blot analysis of protein expression in transduced Dbt cells. Nuclear extracts (20 μg/lane) were prepared from cells expressing the designated constructs. The transduced genes are indicated on the top, and the positions of PAX3-FKHR, MYCN, and histone H1 are indicated at the left. B: Soft agar colony assay (left panel) and focus formation assay (right panel) of Dbt cells transduced with control (vector only) or PAX3-FKHR (PF), with or without MYCN; 105 test cells were seeded for the soft agar colony assay and 103 test cells mixed with 106 NIH3T3 cells were seeded for the focus formation assay. Colony and focus numbers are averages of triplicate measurements (±SD). C: Cell growth curves of Dbt cells transduced with control or PAX3-FKHR, with or without MYCN. Cell numbers are averages of triplicate measurements (±SD). The significant difference in growth rate between cells with and without MYCN expression is indicated (*P < 0.05).

To analyze transformation, soft agar colony and focus formation assays were performed. Cells expressing PAX3-FKHR alone failed to demonstrate evidence of transformation in either assay (Figure 1B). However, previous reports indicated that multiple genetic alterations are required to transform human cells.15,16,17 An important role for Myc family proteins in tumorigenesis is evidenced by the finding of elevated Myc proteins in many cancers along with their key role in cell cycle regulation.18 Many human cell culture models of transformation require small t antigen, which inhibits protein phosphatase 2A and results in stabilization and accumulation of Myc protein.15,19 We decided to investigate MYCN as an oncogene in ARMS based on the findings of increased MYCN expression in most cases of ARMS and MYCN gene amplification in a subset of cases of ARMS along with our finding that MYCN collaborates with PAX3-FKHR in NIH3T3 transformation.20 When MYCN was introduced into immortalized human myoblasts with PAX3-FKHR (Figure 1A), the myoblasts scored positive in both soft agar and focus formation assays (Figure 1B). In contrast, cells transduced with vector, MYCN, or PAX3-FKHR alone were not transformed. Of note, the cells expressing MYCN only as well as cells expressing MYCN plus PAX3-FKHR grew faster than cell lines without MYCN (Figure 1C). However, this faster growth in cells expressing MYCN only was not sufficient for transformation (Figure 1B).

We investigated whether the dystrophin deficiency contributed to the transformed phenotype. To correct the dystrophin defect, a lentiviral vector expressing a minidystrophin gene fused with green fluorescent protein13 was introduced into Dbt cells. Fluorescence microscopic detection of green fluorescent protein-expressing cells revealed that greater than 90% of cells were transduced, and Western blot analysis confirmed that the minidystrophin-green fluorescent protein fusion protein was expressed in the transduced cells (data not shown). When these minidystrophin-expressing cells (Dbt-Dys) were transduced with MYCN and PAX3-FKHR, they scored positive in both transformation assays (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), thus indicating that the presence or absence of dystrophin does not have an impact on cell transformation induced by PAX3-FKHR and MYCN.

PAX3-FKHR Collaborates with MYCN to Promote Tumorigenesis in SCID Mice

To study tumorigenesis mediated by PAX3-FKHR and MYCN in vivo, we used a xenograft tumor system in SCID mice. In particular, 106 Dbt cells transduced with PAX3-FKHR and MYCN, or either oncogene and the corresponding vector, or both vectors were injected in an s.c. site of the flank region of SCID mice. In these studies, all mice (four of four) injected with cells expressing both PAX3-FKHR and MYCN developed tumors rapidly; tumors were palpable in 8 days and reached 1.3 cm in size in 21 days. Surprisingly, all mice (four of four) injected with cells expressing PAX3-FKHR only also showed tumor formation, but at a very slow rate; tumors were palpable at 21 days and 1.3-cm size tumors were formed in 38 days. Cells transduced with MCYN or vector only did not show any tumor formation during the 52-day observation period.

Similar results were obtained with an i.m. injection of 5 × 105 Dbt cells into the hindlimb of SCID mice. Although cells transduced with vector or MYCN alone did not show any tumors during the 52-day observation period, all (four of four) mice injected with cells expressing both PAX3-FKHR and MYCN developed tumors rapidly; by 28 days, the diameter of the injected limb was 1.5 cm compared with a 0.8-cm diameter of the opposite uninjected limb. Intramuscular injection of cells expressing PAX3-FKHR alone also resulted in delayed tumor formation; the injected limb reached a diameter of 1.5 cm in 50 days. Further analysis of mice with s.c. or i.m. tumors did not reveal any gross evidence of metastatic disease.

PAX3-FKHR-Expressing Myoblast-Derived Tumors Are Myogenic and Invasive

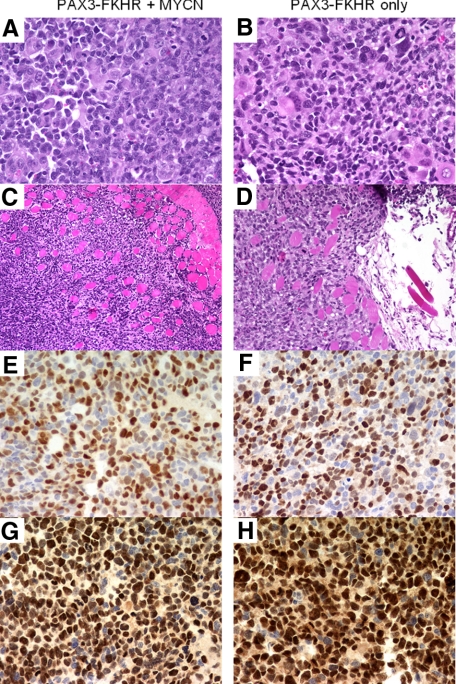

To further characterize these s.c. and i.m. tumors, multiple samples were examined microscopically with standard H&E staining. At high power, this analysis revealed that the tumor cells can be divided into several populations (Figure 2A). One major population consists of small- to intermediate-sized cells with pleomorphic nuclear features, conspicuous nucleoli, and sparse to moderate amounts of cytoplasm. A second subset consists of large cells with large vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Finally, there are rare tumor giant cells, which are similar to the giant cells seen in ARMS. Although these tumors do not demonstrate the typically monotonous small round cell appearance of many human ARMS tumors, they are similar to the subset of human ARMS that contain giant cells, with the small- and intermediate-sized population resembling the small cells of ARMS and the large and giant cells reflecting a higher than usual number of differentiated cells. A high proliferative rate was indicated by frequent mitoses in all high-power fields. At lower power, the tumors tended to be circumscribed with occasional areas of invasion into surrounding muscle fibers and adipose tissue, indicative of a malignant neoplasm (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemical staining with the myogenic markers desmin, muscle-specific actin, MyoD1, and myogenin demonstrated strong reactivity, consistent with the diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma (Figure 2, E and G). In particular, the percentage of cells demonstrating nuclear myogenin reactivity was high, a finding that is frequent in ARMS tumors. These histopathological findings are similar in both s.c. and i.m. tumors and in tumors from cells expressing PAX3-FKHR with or without MYCN (Figure 2, B, D, F, H).

Figure 2.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses of myoblast-derived tumors. A and B: High-power view of cells in tumor (H&E; original magnification, ×400). C and D: Low-power view of tumor cells infiltrating into surrounding skeletal muscle from i.m. tumor (H&E; original magnification, ×200). E and F: Expression of myogenin by tumor cells (original magnification, ×400). G and H: Expression of MyoD1 by tumor cells (original magnification, ×400). Tumors were derived from myoblasts transduced with PAX3-FKHR and MYCN (A, C, E, and G) or PAX3-FKHR alone (B, D, F, and H).

In addition to histological characteristics, a gene expression signature has been defined in fusion-positive ARMS tumors, consisting of PAX3-FKHR target genes and other effects.2,3 To further confirm that the tumors derived from MYCN/PAX3-FKHR-transduced myoblasts have similar molecular characteristics relative to ARMS, qRT-PCR analyses were performed for MYCN (endogenous), CXCR4, FGFR4, MYOD1, and KCNN3. The qRT-PCR assays reveal that expression of all five genes tested was increased to varying degrees in PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-expressing cells and then further increased in tumor-derived cells (Supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Xenograft Tumors Were Selected from a Subset of Parental Cells

To further characterize both s.c. and i.m. xenograft tumors, we used viral integration sites as clonal markers to examine whether tumors were composed of the same cell population as the transduced myoblasts. Restriction endonuclease-digested genomic DNA was analyzed by Southern blot/hybridization analysis with probes from the retroviral constructs. When the puromycin or hygromycin resistance gene was used as a probe, DNA from parental cells transduced with PAX3-FKHR with or without MYCN showed a hybridization pattern different from that of the DNA from corresponding s.c. and i.m. tumors, with some smaller differences among tumor samples (Figure 3, A and B). These findings reveal important differences between cells before injection and cells comprising the actual tumors and suggest that tumors developed from similar but not identical subsets of parental cells. The results suggest that there is selection of a subset of transduced myoblasts with properties that favor tumor progression.

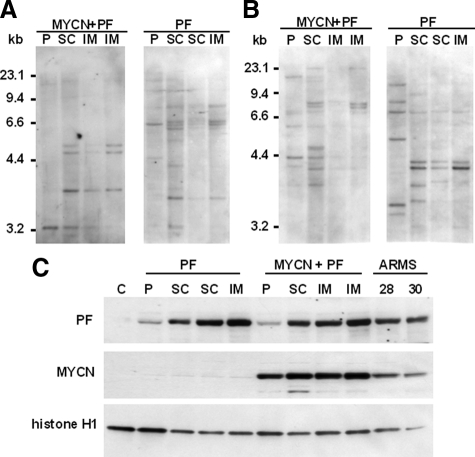

Figure 3.

Characterization of tumors, tumor-derived cells, and parental cells. A: Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from parental cells (P) transduced with PAX3-FKHR (PF) and/or MYCN, and from tumors (subcutaneous [SC] or intramuscular [IM]) derived from these parental cells. Southern blots were hybridized with a probe for the puromycin resistance gene. The sizes of DNA molecular weight markers are shown on the left. B: Southern blot analysis of the same DNA samples with a probe for the hygromycin resistance gene. C: Western blot analysis of PAX3-FKHR and MYCN expression in parental cells transduced with PAX3-FKHR and/or MYCN, in cultured cells from tumors (SC or IM) derived from these parental cells and ARMS cell lines (Rh28 and Rh30). Lanes (loaded with 20 μg of nuclear protein) are labeled on the top, and positions of PAX3-FKHR, MYCN, and histone H1 (loading control) are indicated at the left.

Next, we compared PAX3-FKHR expression in parental and tumor cells. After expanding cells from individual tumors in culture, we prepared nuclear extracts and performed Western blot analysis. This analysis showed that PAX3-FKHR expression is much higher in tumor cells than in myoblasts transduced with PAX3-FKHR with or without MYCN (Figure 3C). The PAX3-FKHR expression level in the tumor cells is comparable with or even greater than the level in ARMS cell lines. Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis indicated that PAX3-FKHR expression is also increased at the RNA level in both tumors and tumor-derived cells (data not shown). The finding of increased PAX3-FKHR mRNA in tumors as well as cell lines derived from these tumors indicates that this expression change is not related to cell culture. In addition, comparison of the growth rate in culture showed very little difference between parental cells and corresponding tumor cells (Supplemental Figure S3, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), thus indicating that tumor cells tolerate higher PAX3-FKHR levels without overt toxic effects. These data suggest that molecular mechanisms requiring high PAX3-FKHR expression in human ARMS tumors are also active in this myoblast xenograft model. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the presence of a collaborating alteration that allows tumor cells to tolerate high-level PAX3-FKHR expression.

High PAX3-FKHR Expression in a Subset of Parental Cells Is Necessary for Transformation

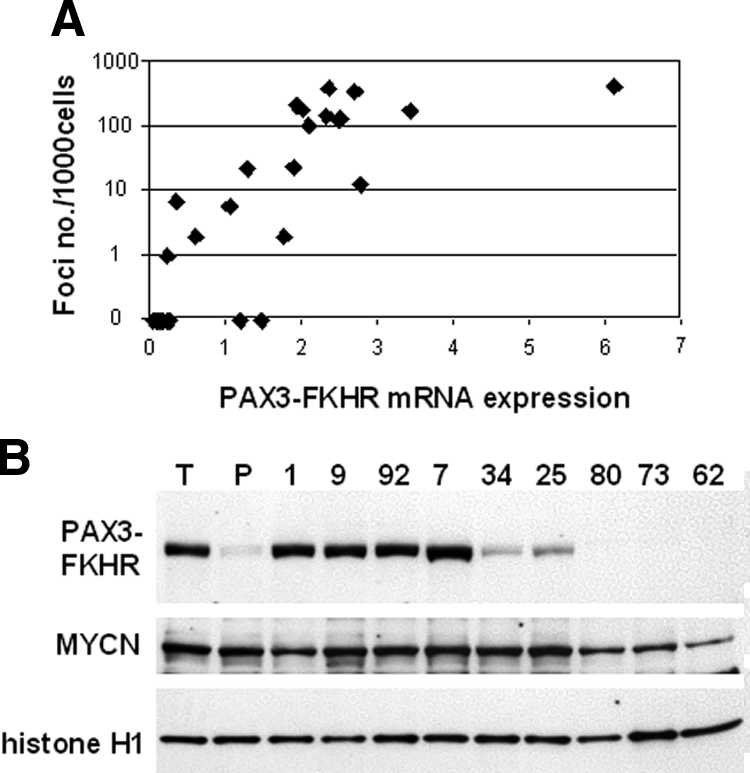

In the preceding experiment, PAX3-FKHR up-regulation may be a new change that occurs during tumorigenesis, or the cells with high PAX3-FKHR expression and collaborating events may preexist in the population and be selected during tumorigenesis. To test this latter hypothesis directly, we subcloned a population of PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-expressing myoblasts by limiting dilution and isolated 100 subclones. These subclones were initially screened by focus formation, revealing 10 subclones with greater than 100 foci per dish (high), 8 subclones with 1 to 25 foci per dish (medium), and 82 subclones with no foci (low). PAX3-FKHR mRNA was measured in all high and medium subclones and in 20 low subclones by qRT-PCR. There was an overall association between expression and focus formation with mean PAX3-FKHR mRNA levels in the high, medium, and low categories of 2.58 ± 1.32, 1.20 ± 0.87, and 0.21 ± 0.38, respectively (Figure 4A). The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.804 (P < 0.001, two-tailed), indicating that there is significant correlation between focus formation and the PAX3-FKHR expression level in these clones. Western blot analysis of PAX3-FKHR protein expression also generally correlated with qRT-PCR data (Figure 4B). In particular, there was high-level PAX3-FKHR protein expression in most high subclones, which was comparable with the level seen in the myoblast-derived tumors. These findings indicate that a small subset of high PAX3-FKHR-expressing cells preexists within PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-expressing myoblasts and when injected into mice, these cells are apparently selected during tumorigenesis.

Figure 4.

Analysis of PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-transduced myoblast subclones. A: Comparison of focus formation and PAX3-FKHR expression in myoblast subclones. The focus formation assay was performed as described in the legend to Figure 1. PAX3-FKHR mRNA was assayed by qRT-PCR and normalized for 18S expression. B: Western blot analysis of subclones. Nuclear extracts (20 μg/lane) were prepared from selected high (1, 9, 92, and 7), medium (34 and 25), and low (80, 73, and 62) subclones as well as myoblast-derived tumor (T) and parental (P) samples. The samples are indicated at the top, and the position of PAX3-FKHR, MYCN, and histone H1 are indicated at the left.

To examine whether intrinsic heterogeneity in the starting population is responsible for the high and low PAX3-FKHR-expressing subclones, we isolated four subclones from the initial myoblast population before any manipulation and transduced each with PAX3-FKHR and MYCN. If the heterogeneity demonstrated in the former experiment exists in the initial population, we expect that most subclones would express low to undetectable PAX3-FKHR levels and show no focus formation. In contrast, each subclone expressed a similar PAX3-FKHR protein level, which was comparable with the level in the original PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-transduced population (Supplemental Figure S4A, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Furthermore, the four subclones tested all showed transforming activity (Supplemental Figure S4B, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In these control experiments, we acknowledge that we analyzed only four clones from the population, which do not necessarily represent the whole parental population and may not have reproduced all of the effects that would be generated in a heterogeneous population. However, our findings do not support the premise of intrinsic heterogeneity in the starting population as the cause for heterogeneity in the PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-transduced myoblast population.

To provide further evidence for our hypothesis that high-level PAX3-FKHR expression in transduced myoblasts is necessary for tumorigenesis, two subclones with high PAX3-FKHR expression and two subclones with very low expression were injected subcutaneously into SCID mice. During the 43-day observation period, the two subclones with high PAX3-FKHR expression produced tumors (each occurring in four of four mice) and the two subclones with low expression did not produce tumors. These data support our hypothesis that high-level PAX3-FKHR expression in the transduced myoblasts is necessary for tumorigenesis.

Oncogenic Significance of High PAX3-FKHR Expression

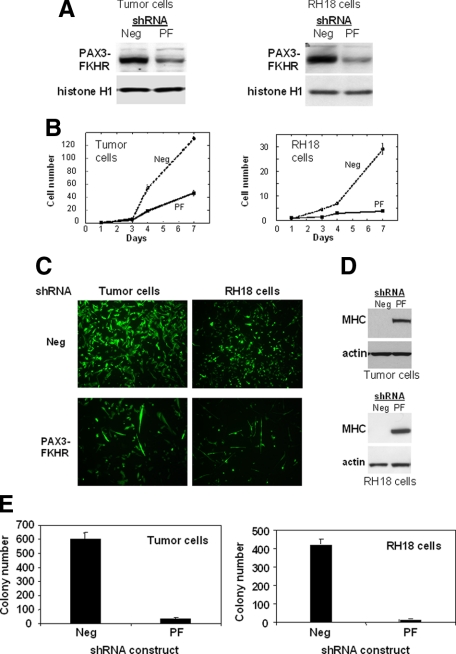

To further study the role of high PAX3-FKHR expression in oncogenesis, retroviral constructs containing an shRNA directed to the PAX3-FKHR fusion point and a negative control shRNA were introduced into the myoblast-derived tumor cells. In parallel to the studies with the myoblast-derived tumor cells, shRNA constructs were also introduced into a human ARMS cell line (Rh18) to assess whether PAX3-FKHR is functioning comparably in the myoblast system. In contrast with published studies using siRNA oligonucleotides, which only have a transient effect,21 this stable shRNA expression strategy exerts a sustained effect and allows more assays of oncogenic function to be performed. Western blot analysis of myoblast-derived tumor cells and Rh18 cells harvested 3 days after transduction showed a significant decrease in PAX3-FKHR expression in cells transduced with the test construct compared with cells transduced with control constructs (Figure 5A). When each of these PAX3-FKHR shRNA-treated cells was plated in a dish, there was a decreased rate of cell accumulation compared with that for the negative control (Figure 5B). Staining with trypan blue did not reveal many dying cells and thus decreased accumulation is mostly attributed to decreased proliferation. This decreased accumulation was also documented by fluorescence microscopy for both tumor cell types (Figure 5C). Among the detectable cells treated with PAX3-FKHR shRNA, multiple cells showed elongated morphology, suggestive of myogenic differentiation. Western blot analysis revealed increased expression of myosin heavy chain, a late myogenic marker, compared with no detectable myosin heavy chain in control shRNA-treated cells (Figure 5D). Furthermore, a soft agar colony formation assay revealed a dramatic decrease in the transformation ability of PAX3-FKHR shRNA-treated cells compared with that of control shRNA-treated cells (Figure 5E). Therefore, both ARMS and PAX3-FKHR/MYCN-transduced myoblast tumor cells are dependent on PAX3-FKHR for proliferation, transformation, and inhibition of myogenic differentiation.

Figure 5.

Effects of shRNA against PAX3-FKHR in myoblast-derived tumor and ARMS cells. A: Analysis of PAX3-FKHR protein expression. Retroviral constructs with shRNA against PAX3-FKHR (PF) or a negative control (Neg) were transduced into myoblast-derived tumor and Rh18 ARMS cells. After 3 days, protein was extracted and analyzed by Western blot analysis as described in Figure 1. B: Cell growth analysis. PAX3-FKHR shRNA- and control-transduced cells were plated in plastic dishes and counted at designated time points. C: Fluorescence microscopic analysis of PAX3-FKHR shRNA- and control-transduced cells 7 days after transduction. D: Protein analysis of myogenic differentiation. Extracts were prepared 6 days after transduction and analyzed by Western blot. E: Soft agar colony analysis of PAX3-FKHR shRNA- and control-transduced cells (as described in the legend to Figure 1).

Discussion

In this report, we present evidence indicating that PAX3-FKHR and MYCN promote oncogenic changes in immortalized human myoblasts, both in culture and in mice. Although the transduced myoblasts express a low overall PAX3-FKHR level, the tumors express a higher PAX3-FKHR level, which is similar to that in ARMS cell lines and tumors. Comparison of the clonal markers of the starting and tumor cell populations revealed that only a subset of cells from the starting population are present in the tumor. Furthermore, subcloning of the original population identified a small subset of high PAX3-FKHR-expressing clones that have high transforming and tumorigenic activity in contrast with the majority of low PAX3-FKHR-expressing clones without transforming or tumorigenic activity. Similarities in the clonal composition of several tumors derived from the same original transduced population indicate that a similar spectrum of high PAX3-FKHR-expressing transformed cells is selected to generate these tumors. These findings strongly point to the conclusion that there is a critical threshold level of PAX3-FKHR needed for oncogenic activity and that cells with a sufficiently high PAX3-FKHR level are selected for their oncogenic properties. Our previous studies in human tumors showing consistently increased expression of PAX3-FKHR relative to that of wild-type PAX3 indicate the relevance of this model system to human ARMS.4 Furthermore, this expression threshold was more recently evidenced by expression profiling studies showing that tumors with ARMS histology expressing very low levels of the PAX3-FKHR fusion transcript have a global expression pattern more similar to that of fusion-negative embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas than fusion-positive ARMS tumors.2,3

Based on the growth suppression induced in immortalized murine cells by PAX3-FKHR levels that normally occur in ARMS tumors,7 we hypothesized that additional alterations occur in ARMS and permit these cells to tolerate the toxic effects of the fusion protein. In additional studies using inducible PAX3-FKHR constructs in human Dbt myoblasts, we confirmed that the growth-suppressive effects of PAX3-FKHR also occur in the setting of this human myogenic cell line (S. J. Xia and F. G. Barr, unpublished observations). In the current study, we found high PAX3-FKHR expression (similar to the level in ARMS cell lines and tumors) in xenograft tumors and in rare subclones of the parental transduced myoblast line, but did not find evidence of growth suppression in these subclones or tumor lines. These findings indicate that these high PAX3-FKHR-expressing subclones and myoblast-derived tumor cells tolerate this high PAX3-FKHR expression level. These findings are consistent with the premise that an alteration occurred in rare cells to permit these cells to tolerate high PAX3-FKHR levels (which are potentially expressed from the vector in the initial population) and then these cells survived in the initial population and were subsequently selected during tumorigenesis. In a previous study with an inducible PAX3-FKHR construct in NIH3T3 cells, we did not identify a gene that would attenuate the growth-suppressive effects of high-level PAX3-FKHR expression from among a small series of candidate oncogene alterations that occur in ARMS tumors.12 The available human myoblast subclones and tumors will provide a useful system for analyzing collaborating events that attenuate PAX3-FKHR toxicity.

The finding of a susceptibility for rhabdomyosarcomas to develop in mdx mice, which have mutant dystrophin,22 raises the question whether the lack of a functional dystrophin protein in muscle progenitors may have a direct impact on transformation and tumorigenesis. We addressed this question directly by demonstrating that addition of a functional minidystrophin protein does not interfere with transformation by PAX3-FKHR and MYCN (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), and thus the role of the dystrophin deficiency in these oncogenic events seems to be minimal or absent. It should also be noted that tumors occur in mdx mice at old age (mean of 20 months, with a 22-month life span),22 suggesting that dystrophin deficiency does not directly contribute to tumorigenesis but rather that genetic alterations most likely accumulate in the continuously regenerating muscle cells of dystrophic muscle.

We note the interesting finding that PAX3-FKHR alone did not show a positive score in either of the cell culture assays of oncogenic transformation but was capable of promoting xenograft tumors in SCID mice at both s.c. and i.m. sites. In the latter assay, the kinetics of development of tumors from cells expressing PAX3-FKHR alone was substantially slower than that of cells expressing both PAX3-FKHR and MYCN. The difference between the cell culture and mouse assay results suggests that the tissue microenvironment may play a role in the tumorigenesis process.23 The in vivo mouse environment apparently provides more suitable conditions that allow the oncogenic cells to grow, whereas the cell culture environment (medium, cocultured cells, growth factors, and others) does not provide a favorable set of conditions. Based on this evidence, the in vivo environment seems to be a more sensitive assay for oncogenic behavior than the cell culture assays.

Despite differences in myoblast-derived tumors from human ARMS, our phenotypic studies revealed that high PAX3-FKHR expression has a similar oncogenic role in myoblast tumor-derived cells and ARMS cells. When PAX3-FKHR expression was decreased to low levels by shRNA, both cells demonstrated very similar responses. In particular, both ARMS and myoblast-derived tumor cells were dependent on high PAX3-FKHR expression for proliferation, transformation, and inhibition of myogenic differentiation. These findings corroborate and extend previous studies in which other ARMS lines were treated with small interfering RNA oligonucleotides, and thus the dependence of the ARMS oncogenic phenotype on high PAX3-FKHR is consistent in multiple ARMS lines with different RNA interference techniques.21

This model system joins two other recently reported xenograft models of PAX3-FKHR-induced RMS. In one model, PAX3-FKHR was introduced into murine bone marrow stromal cells, which have mesenchymal stem cell properties. Addition of simian virus 40 early region (or large T or dominant-negative p53) and mutant ras resulted in transformed cells that form tumors resembling ARMS when injected into mice.24 In a second model, expression of PAX3-FKHR in primary human myoblasts selects for loss of p16 expression to bypass senescence.25 Addition of MYCN and TERT then produces cells that are able to form myogenic tumors when injected into mice.26 Although there are differences among these three systems, each model reveals similarities to human ARMS, and thus each will have utility in further investigating the pathogenesis of this gene fusion-associated cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Parham (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center) for his contribution to the histological review.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Frederic G. Barr, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, 505C Stellar Chance Laboratories, 422 Curie Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104-6082. E-mail: barrfg@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA64202 and 104896 to F.G.B.), the Joanna McAfee Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant to F.G.B.), and the Alveolar Rhabdomyosarcoma Research Fund.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Barr FG. Gene fusions involving PAX and FOX family members in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2001;20:5736–5746. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davicioni E, Finckenstein FG, Shahbazian V, Buckley JD, Triche TJ, Anderson MJ. Identification of a PAX-FKHR gene expression signature that defines molecular classes and determines the prognosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6936–6946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebauer M, Wachtel M, Niggli FK, Schafer BW. Comparative expression profiling identifies an in vivo target gene signature with TFAP2B as a mediator of the survival function of PAX3/FKHR. Oncogene. 2007;26:7267–7281. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ, Barr FG. Fusion genes resulting from alternative chromosomal translocations are overexpressed by gene-specific mechanisms in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8047–8051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidler S, Fredericks WJ, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Barr FG, Vogt PK. The hybrid PAX3-FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma transforms fibroblasts in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9805–9809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam PY, Sublett JE, Hollenbach AD, Roussel MF. The oncogenic potential of the Pax3-FKHR fusion protein requires the Pax3 homeodomain recognition helix but not the Pax3 paired-box DNA binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:594–601. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia SJ, Barr FG. Analysis of the transforming and growth suppressive activities of the PAX3-FKHR oncoprotein. Oncogene. 2004;23:6864–6871. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudre-Mauroux C, Occhiodoro T, Konig S, Salmon P, Bernheim L, Trono D. Lentivector-mediated transfer of Bmi-1 and telomerase in muscle satellite cells yields a Duchenne myoblast cell line with long-term genotypic and phenotypic stability. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1525–1533. doi: 10.1089/104303403322495034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JJ, Scheijen B, Voncken JW, Kieboom K, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Bmi-1 collaborates with c-Myc in tumorigenesis by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis via INK4a/ARF. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2678–2690. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia SJ, Pressey JG, Barr FG. Molecular pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:97–104. doi: 10.4161/cbt.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutomi K, Possemato R, Wong JM, Currier JL, Tothova Z, Manola JB, Ganesan S, Lansdorp PM, Collins K, Hahn WC. The telomerase reverse transcriptase regulates chromatin state and DNA damage responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8222–8227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503095102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia SJ, Rajput P, Strzelecki DM, Barr FG. Analysis of genetic events that modulate the oncogenic and growth suppressive activities of the PAX3-FKHR fusion oncoprotein. Lab Invest. 2007;87:318–325. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Kimura E, Fall BM, Reyes M, Angello JC, Welikson R, Hauschka SD, Chamberlain JS. Stable transduction of myogenic cells with lentiviral vectors expressing a minidystrophin. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1099–1108. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FG, Smith LM, Lynch JC, Strzelecki D, Parham DM, Qualman SJ, Breitfeld PP. Examination of gene fusion status in archival samples of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma entered on the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study-III trial: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:202–208. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn WC, Counter CM, Lundberg AS, Beijersbergen RL, Brooks MW, Weinberg RA. Creation of human tumour cells with defined genetic elements. Nature. 1999;400:464–468. doi: 10.1038/22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Nakagawa H, Navaraj A, Naomoto Y, Klein-Szanto AJ, Rustgi AK, El-Deiry WS. Tumorigenic conversion of primary human esophageal epithelial cells using oncogene combinations in the absence of exogenous Ras. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10415–10424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardic CM, Downie DL, Qualman S, Bentley RC, Counter CM. Genetic modeling of human rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4490–4495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson JA, Cleveland JL. Myc pathways provoking cell suicide and cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:9007–9021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JD, Hahn WC. Involvement of PP2A in viral and cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2005;24:7746–7755. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado GE, Xia SJ, Zhang C, Ahn EH, Gustafson DM, Lae M, Ladanyi M, Barr FG. Identification of PAX3-FKHR-regulated genes differentially expressed between alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: focus on MYCN as a biologically relevant target. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:510–520. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi K, Tsuchiya K, Otabe O, Gotoh T, Tamura S, Katsumi Y, Yagyu S, Tsubai-Shimizu S, Miyachi M, Iehara T, Hosoi H. Effects of PAX3-FKHR on malignant phenotypes in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain JS, Metzger J, Reyes M, Townsend D, Faulkner JA. Dystrophin-deficient mdx mice display a reduced life span and are susceptible to spontaneous rhabdomyosarcoma. FASEB J. 2007;21:2195–2204. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7353com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzukerman M, Rosenberg T, Reiter I, Ben-Eliezer S, Denkberg G, Coleman R, Reiter Y, Skorecki K. The influence of a human embryonic stem cell-derived microenvironment on targeting of human solid tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3792–3801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren YX, Finckenstein FG, Abdueva DA, Shahbazian V, Chung B, Weinberg KI, Triche TJ, Shimada H, Anderson MJ. Mouse mesenchymal stem cells expressing PAX-FKHR form alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas by cooperating with secondary mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6587–6597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardic CM, Naini S, Herndon JE, 2nd, Kesserwan C, Qualman SJ, Counter CM. The PAX3-FKHR fusion gene of rhabdomyosarcoma cooperates with loss of p16INK4A to promote bypass of cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6691–6699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naini S, Etheridge KT, Adam SJ, Qualman SJ, Bentley RC, Counter CM, Linardic CM. Defining the cooperative genetic changes that temporally drive alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9583–9588. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.