Abstract

This study examined the extent of tobacco industry funding of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) organisations and whether leaders of these organisations thought tobacco was a priority health issue for their community. We interviewed leaders of 74 LGBT organisations and publications in the USA, reflecting a wide variety of groups. Twenty-two percent said they had accepted tobacco industry funding and few (24%) identified tobacco as a priority issue. Most leaders did not perceive tobacco as an issue relevant to LGBT identity. They saw smoking as a personal choice and individual right rather than as a health crisis fuelled by industry activities. As such, they were reluctant to judge a legal industry, fearing it might lead to having to evaluate other potential funders. They saw tobacco control as divisive, potentially alienating their peers who smoke. The minority who embraced tobacco control saw the industry as culpable and viewed their own roles as protecting the community from all harms, not just those specific to the gay community. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender tobacco-control advocates should reframe smoking as an unhealthy response to the stresses of homophobia to persuade leaders that tobacco control is central to LGBT health.

Keywords: LGBT, community health, tobacco control, tobacco industry, licit and illicit substances

Introduction

Studies conducted across a range of contexts suggest that lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender (LGBT) people smoke more than the total population (Diamont et al. 2000, Ryan et al. 2001, Thiede et al. 2003, Tang et al. 2004). One recent study in California (Baezconde-Garbanati 2003) noted that smoking prevalence among gay men and women was higher than for any other demographic group in the state. Another (Bye et al. 2005) found that gay and bisexual men smoked 50% more than all men; lesbian and bisexual women smoked three times as much as all women. The prevalence rate for transgender Californians was 30.7%, twice the rate for all Californians (Bye et al. 2005). Tobacco use is estimated to cause the premature death of one-in-two longtime users (Doll et al. 1994), therefore high rates of smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people should be a concern for the community. This study explored how LGBT leaders view tobacco and tobacco industry activities and how an understanding of those views might help advocates reduce tobacco use in the community.

Historically, LGBT people have been stigmatised and ostracised (D’Emilio 1983, Streitmatter 1995). As this began to lessen in the late twentieth century, tobacco companies started to view the LGBT community in the USA as a market. In 1992, the tobacco industry began placing advertisements in gay publications (Smith and Malone 2003) and supporting LGBT organisations (Offen et al. 2003), as it had earlier established ties with other minority communities (Yerger and Malone 2002). Previous research suggests that such tobacco industry outreach is undertaken to normalise tobacco use, gain support for industry positions and thwart community tobacco-control efforts (Yerger and Malone 2002, Portugal et al. 2004, Stone and Siegel 2004). Thus, how community leaders view the tobacco industry is relevant to public health efforts.

Theoretical framework

Problems (such as tobacco use) are recognized not simply because of their objective harms, but rather through a complex process of social definition. Hilgartner and Bosk (1988: 60) suggest that ‘people’s selections of the social conditions that trouble them’ are influenced by their ‘master statuses’, the identities most central to their self-image. However, how people decide whether specific problems are crucial to that status is a complex, socially influenced process. Hilgartner and Bosk theorize that issues compete for space in public arenas with limited ‘carrying capacities’ for the number of social problems that can be addressed at any one time. Minority communities may have an especially difficult time determining which issues to prioritise. They are affected —frequently disproportionately so — by problems common to larger populations, such as breast cancer or drunk driving. In addition, they have the extra burden of problems specific to them, such as racism or the need for bilingual education. Which of these issues are regarded as important by leadership depends on numerous social, political, economic and other factors.

An issue becomes problematised when advocates make the case that it is ‘caused by human actions and amenable to human intervention’ rather than the result of nature, accident or fate (Stone 1989: 281). The strategic portrayal of ‘causal stories’ is essential to problem definition. Advocates have attempted in the last two decades to focus attention on the tobacco industry as the causative factor in the tobacco-related disease epidemic (Yach and Bettcher 2000). This causal narrative posits a powerful opponent. However, it also formulates tobacco as an issue amenable to organisational or political intervention. Previously, advocates had most often framed tobacco as a matter to be addressed by individual action, i.e. smoking cessation. Both individual and social/environmental approaches may be more effective when the dynamics between individual and environmental factors are taken into account (Stokols 1992).

Despite high rates of tobacco use and tobacco industry presence within the LGBT community, tobacco control has not been a visible priority for LGBT organisations. This study suggests two reasons for this. First, LGBT leaders do not perceive tobacco as relevant to LGBT identity. Second, LGBT leaders have not universally adopted the tobacco-control movement’s redefinition of the ‘tobacco problem’ as caused by tobacco industry activity. Therefore, they may regard dealing with tobacco as a matter of making judgements about their peers, rather than confronting an external source of harm to the community.

Methods

In the study reported on in this paper, we interviewed leaders of LGBT organisations in the USA (n=74) to explore their perceptions of the extent and significance of tobacco use and tobacco industry presence in the community. Using web-based resource lists of LGBT organisations and publications compiled by umbrella groups such as the National Association of LGBT Community Centers (2002), and the National Coalition for GLBT Youth (2002), we selected the largest and most prominent national and regional groups known to us. Our grant’s advisory board, composed of national experts in tobacco control and the LGBT community, assisted in the selection process. We sought to include different kinds of community groups. We contacted the heads of newspapers, magazines, political organisations, community centres, health groups, AIDS organisations, food banks, parade committees, street fairs, film festivals and other LGBT community institutions. We interviewed executive directors, editors, publishers or their high-level associates who were familiar with their organisation’s history of policy-making.

Sample selection

We mailed introductory letters to 100 community leaders and followed-up with telephone calls. We informed contacts that we were studying LGBT leadership perspectives on tobacco industry involvement and smoking in the community and asked permission to tape a 10–30 minute confidential telephone interview. Thirteen leaders failed to respond after a minimum of four calls, including those representing seven media organisations, two community centres, two political organisations, one film festival and one social group. Twelve refused to participate, reflecting five political organisations, three AIDS organisations, two film festivals and two media organisations, saying they had no interest in the study, were too busy to take part or had nothing of value to contribute. Another leader, the head of an AIDS organisation, withdrew after the interview with no explanation. According to public records, among the 26 non-participating organisations, three of the four AIDS groups, two of the seven political groups and two of the nine media outlets had accepted tobacco industry money.

Procedures and data analysis

Audiotaped telephone interviews were conducted between September 2002 and July 2004 using a semi-structured interview guide. We asked community leaders about their funding sources and whether they had been asked to do anything for funders (such as publicize support, take a position on an issue or promote a product); whether they had solicited or accepted advertisements, sponsorships or donations from the tobacco industry; whether and how they took organisational policy positions; whether and how they had adopted a tobacco-related policy; what they considered the most important LGBT health issues; what their experiences were with tobacco-control organisations; and the extent to which they viewed tobacco as an issue of concern for the community. Quantifiable data, such as organisation type, presence or absence of policy regarding tobacco money, and health concerns named were analysed using descriptive statistics. Textual data were coded and iteratively reviewed by the authors and two research assistants to identify major themes inductively, using an approach consistent with tenets of interpretive social science (Rabinow and Sullivan 1979). Further analysis involved repeated readings of the text in an effort to understand leaders’ responses as making sense from within their world.

Results

Two principal themes emerged from analysis: first, the majority of leaders believed that tobacco control was extraneous to their missions and, second, tobacco use was largely seen as an issue of individual choice. However, almost all the leaders reported that their organisations had at least discussed tobacco-related concerns. These included whether or not to adopt smokefree policies in their workplaces, accept tobacco industry sponsorship or advertising or devote organisational resources to addressing tobacco as an LGBT health concern. Twenty-two percent (n=16) of leaders reported that they had accepted funding from the tobacco industry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of groups by acceptance of tobacco industry money (n=74).

| Accepted industry funding | No industry funding* | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publications | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Health/AIDS groups, food banks | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Political groups | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Parades, fairs, film festivals | 1 | 10 | 11 |

| Community centers | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Other | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Total all respondents (%) | 16 (22) | 58 (78) | 74 (100) |

These organizations may have declined or never been offered industry funding.

Tobacco control as extraneous to LGBT priorities

More pressing concerns

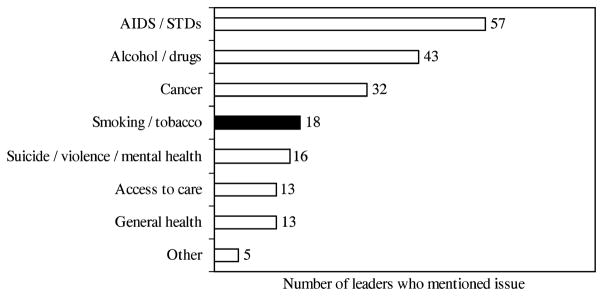

Tobacco control was not a priority for the majority of the leadership: only 24% of leaders (n=18) named tobacco as one of the three most pressing LGBT community health concerns (Figure 1). One editor explained that tobacco control was not a priority for LGBT organisations because ‘Issues that can only be addressed by gay activists…take priority over issues that are also being addressed by the general populace’. Similarly, a community centre director said, ‘We’ll do it [tobacco-control activity] as long as it doesn’t bother any of the important stuff that we’re doing’. Anything that was perceived to distract from core missions was problematic. Few leaders felt that their organisations had the capacity to engage in tobacco-control activities.

Figure 1.

Health issues of concern to LGBT leaders.* Leaders were asked to name the three health issues they thought were of greatest concern to the LGBT community. Not all respondents named three issues and several catagories were consolidated.

Tobacco was also frequently regarded as less important than other problems to LGBT individuals. The head of a community centre said that tobacco was ‘often just not an issue for a person who’s got a lot going on in their life in terms of mental health, self-esteem, self-worth, probable alcohol abuse, club drugs, etc’. The LGBT community has higher rates of alcoholism and drug use (Stall and Wiley 1988, McKirnan et al. 2006) and suicide (Ploderl and Fartacek 2005) than the mainstream, as well as higher rates of tobacco use (Ryan et al. 2001, Tang et al. 2004, Bye et al. 2005, Greenwood et al. 2005). The problem of smoking was not a priority because other problems were more immediate and devastating.

These other issues were perceived to be more damaging to both the individual and the community. The head of a religious organisation suggested that tobacco competed poorly with alcohol as an LGBT issue: ‘If you’re going to make tobacco the bad guy, alcohol has to be equally the bad guy’. He suggested that ‘alcohol kills actively’ (e.g. through drinking irresponsibly and driving drunk) as opposed to tobacco killing ‘passively’. The head of an AIDS food bank also thought that ‘alcohol kills far more people…People don’t miss work because they smoked too much the night before and they don’t trash company cars…and have unsafe sex and all that with tobacco’. Tobacco was perceived to be risky primarily to the user and not associated with bad behaviour, whereas alcohol abuse was perceived to be a public harm with dramatic consequences for the individual and the community.

For some respondents, tobacco was not regarded as an LGBT health priority because of its association with identity-forming experiences for LGBTs. For example, the head of an AIDS service centre observed, ‘Drinking and smoking have been part of most lesbians’ coming out that I know of’. A magazine editor agreed: ‘So much of our [gay] culture revolves around alcohol and tobacco’. The normalisation of smoking as part of the coming out process made it difficult for respondents to see tobacco use as a threat.

‘Business decisions’

Reluctance to prioritise tobacco control may have been related to funding considerations, a concern for many non-profit organisations. Tobacco company sponsorship or support was described as important to LGBT organisations’ work. While allowing that smoking ‘is considered bad for one’s health’, a pride festival organiser said the decision to accept tobacco industry funding ‘was really a business decision…that helps us make a better festival’. In this locution, the harm of tobacco is a matter of opinion, while the benefit of accepting industry money is clear and concrete.

The head of an LGBT chamber of commerce believed his organisation would have taken tobacco industry money in the past, ‘just because of the [financial] situation they were in’. However, he added that, ‘this year, they’re more solvent, so I think that they would think twice about it’. An editor spoke of similar constraints: ‘We weren’t about to cut ourselves off from any potential advertising income from tobacco companies’. She felt it was ‘fiscally necessary and defensible ideologically’ to her readers. Like many respondents who accepted tobacco industry funding, these leaders volunteered justifications for doing so, suggesting that the decision was problematic. ‘When financial times are hard and somebody’s waving money at you, I understand that it’s hard’ noted an editor of a lesbian publication with a policy against taking tobacco advertisements. She expressed empathy for the tenuous financial situation in which many leaders found themselves.

The responses of several leaders indicated that, for them, ties to tobacco companies were a painful price of organisational effectiveness. The director of a community centre said, ‘If we can take the blood money and use it to do good work, we’re going to take it’. The head of an AIDS service centre that received tobacco industry funding remarked that ‘It’s not a pure world…in an ideal world, we would like not to benefit from anything like that’. Likewise, a director of an AIDS food bank described the money his organisation received as ‘Our tobacco bribe…corruption—that’s what it is’. Accepting a grant from a source he viewed as impure was the cost of keeping his programme solvent.

Some leaders described scenarios in which they might reluctantly accept tobacco money. In a discussion of funding sources, one festival director said he would not seek out tobacco corporations, ‘but at the same time, would not turn them down’. A strategy of passivity mitigated the distaste that actively pursuing tobacco industry contributions might invoke. This distaste could also be reduced by working with industry subsidiaries; the head of an LGBT chamber of commerce thought his organisation would not accept funds directly from Philip Morris, ‘but we would maybe take money from…[then Philip Morris subsidiary] Kraft Foods’. The head of a pride festival committee said his organisation would probably partner with a tobacco company that ‘came to us and said we want to send a no-smoking message out to your youth’. Under the right circumstances even otherwise-reluctant LGBT organisations might engage with the tobacco industry. Leaders did not want to preclude possible funding options for their organisations, but sought to set justifiable funding parameters. That leaders consistently saw the issue as requiring justification suggests an underlying anxiety about the moral dimensions of taking tobacco industry money.

Maintaining solidarity

Leaders also sought to avoid issues that might provoke organisational conflict. One director of a political organisation said, ‘We have a hesitancy about taking on issues that cause internal stress, and this [smoking] is one of them’. Other issues, such as AIDS funding and anti-LGBT initiatives, were seen by this participant as ‘non-controversial’. Those issues — focused on external forces — inspired the organisation to unite; in contrast, she observed, ‘smoking becomes an issue of dividing’. Addressing smoking required drawing distinctions between smoking and non-smoking members, which could harm organisational cohesiveness.

Judging the industry

In many cases, leaders were unwilling to engage in critical assessment of the industry. A director of a political advocacy group told us, ‘We can’t get into judging the morality of different corporations unless their stated purpose opposes our agenda’. In this formulation, only those who self-identified in opposition to the LGBT community warranted attention. Tobacco industry presence in the community fell outside this definition of LGBT issues. This leader added that he did not ‘have the time or the resources to investigate every company’, fearing the expansion of his responsibilities beyond his capacity. An editor said, ‘If I start targeting one company or one industry, based on whether or not I like their product or whether or not they’re doing something that may or may not serve the community or the public at large, I’ve got to do it with everyone’. These leaders seemed anxious to avoid a potential cascade of decision-making that might ensue if they made judgements in any one instance.

A community centre director referred to her organisation’s discussion about ‘sin money’. Although they had not taken any tobacco company funds, they declined to adopt a formal policy against it: ‘The discussion was about, on the one hand, the damage those things [cigarettes] do in our community and on the other hand the slippery slope [of] defining what is good and evil money’. Not wanting to limit her options, she suggested that making distinctions among potential donors could harm her organisation. Many respondents expressed the concern that developing policies against tobacco funding would require them to make similar judgements about other issues, something they were reluctant to do. Making judgements was seen as complicating, if not violating, their core missions. An editor was worried about ‘becoming moral police on what we will and will not run, and then we’d have to have very extensive guidelines to justify to other groups why we do or do not run certain ads’. An aversion to making judgements of others and a desire for consistent policy made many leaders feel that taking a position might lead to more work than they could handle.

The head of an AIDS food bank focused on the tobacco industry employees with whom he dealt. ‘They are involved, progressive, there are many gay and lesbian people themselves. And our conversations are only about how can we do more to relieve the suffering, to help your project, to be more innovative and to get the money where it’s needed’. Social acceptance and the industry’s employment of LGBTs trumped any concerns about alliances with a tobacco company. He added that their ‘corporate interests may be different, but I don’t get involved in that at all’. Compartmentalizing his knowledge about the source of the money allowed him to suspend judgement.

It’s not advertising

Despite the belief that tobacco control was not their responsibility, some leaders expressed reluctance to promote tobacco. The director of a religious group said she might take advertising or sponsorship money from an industry affiliate, ‘but we would not run tobacco ads’. The head of an AIDS service centre that accepted tobacco industry funding argued that it required minimal organisational commitment: ‘I don’t have to advertise [the tobacco company]…the only thing they get is [a mention in] the annual report’. The head of an AIDS food bank emphasised that the tobacco company did not advertise with his organisation: ‘They don’t ask anything in return. We don’t publicise their names. It’s almost an anonymous gift’. These leaders distinguished their financial involvement with the industry from overtly advertising or promoting tobacco; they also minimised any public acknowledgment of their connection to the companies. This sensitivity suggests that their engagement with the industry was problematic.

Individual choice

Avoiding paternalism

Most leaders saw tobacco use as a matter of individual choice. The head of a community centre emphasised the importance of this creed in the LGBT community: ‘Choice is the foundation of most of the civil rights we’re arguing for, choice and privacy’. She cautioned that personal and social responsibility ought to follow from those rights, for example, containing secondhand smoke. The head of an LGBT historical society said that ‘people should have in the American system of checks and balances and freedom, the ability to name their own poisons’. In this view, tobacco use was an issue of almost patriotic stature, a matter of rights and freedom rather than a community health problem of addiction and disease.

Acceptance was an important element of choice. An organiser of a pride festival remarked that, ‘We’re about people accepting who they are and being proud…-not…determin[ing] what they do, what they smoke, don’t smoke, what they drink, what they don’t drink’. The director of a political organisation concurred, saying, ‘A lot of individuals come here and already feel somewhat marginalised…this is…their safe space’. In this view, addressing smoking was equivalent to judging individuals, contrary to the organisations’ mission of instilling acceptance and pride.

Concern about ‘choice’ also led some leaders — particularly editors — to avoid what they saw as paternalism. One publisher said his newspaper took tobacco ads because: ‘Part of our work as activists is to give people a choice to make their own decisions’. He was concerned about using his influence appropriately while, ironically, suggesting that ‘choice’ was something the publication ‘gave’. He added, ‘We shouldn’t make decisions for them by refusing to run such ads’, intimating that refusing tobacco advertisements was tantamount to censorship. Another publisher said, ‘By running advertisements from any company, we weren’t necessarily endorsing their products’. She asserted that it was not her role to judge the product in question; rather, ‘Our readers were smart enough to decide for themselves whether or not they wanted to use them’.

Allowing decisions about tobacco to devolve to the individual level let some interviewees abdicate responsibility for leadership. The director of a pride festival thought peer pressure was critical to promoting a smokefree community, not ‘whether organisations take a position on whether to take tobacco money or not’. When asked if he thought community institutions might influence such peer pressure, he responded, ‘We don’t feel it’s our place to set personal agendas’. On the issue of tobacco money, the head of a film festival described accepting tobacco donations as a way to redeem some good from tobacco’s inevitable harm: ‘People are going to smoke. We’ll take the money’. Such perspectives forward a conception of health behaviours as solely determined by individual factors and minimise the power of media and community organisations to shape health practises.

Organisational tobacco-control policy as an inhibitor of individual choice

Leaders frequently invoked the ‘rights’ of both individuals and tobacco companies. The legality of tobacco was often used to justify having commerce with the tobacco industry. One editor emphasised that, ‘As long as smoking was legal in the US, each and every individual had a right to make a decision whether they were going to smoke or not: therefore they could advertise’. Another agreed: ‘I don’t feel it’s our role to censor that information about legal products’. Such views suggest that the US legal system’s focus on individual rights provides effective justification for continued promotion of lethal products. As a third editor noted: ‘It’s a corporation that has the right to do what they want to do to people who are over 18. It’s not for me to tell someone what product to use or brand to use when they’re smoking’. Some respondents drew comparative analogies. A publisher opined, ‘There are many things that are bad for your health…we don’t outlaw those things’, suggesting that any attempt to address tobacco would equate with prohibition.

For these respondents, the tobacco industry’s legal standing conferred an automatic moral acceptability. Its legal status protected the industry from judgements about its products and practices, especially from a community already disinclined to judge. Furthermore, respondents suggested that taking any organisational stand on tobacco issues was equivalent to censorship or criminalisation. This perception of the power of their actions seemed to contribute to reluctance to act.

Tobacco control as a relevant LGBT issue

A minority of LGBT leaders embraced tobacco control, believing that protecting the community from tobacco-related disease was integral to LGBT leadership. The director of a pride festival spoke of a lucrative sponsorship offer from a tobacco company that her organisation had declined. Her board of directors ‘felt strongly that this is not the issue we wanted out there. It was not within…[our] mission and purpose to accept that kind of sponsorship money’. In this instance, refusing tobacco funding was seen as consistent with the organisation’s mission.

Some leaders saw industry activities as contrary to LGBT goals. For example, one director of a health centre asserted, ‘I don’t want to see the gay community become the target of alcohol and tobacco companies. These people are not invested in our overall survival as a people’. The leader of a political organisation explained why she thought her organisation would not accept tobacco money: ‘…partly because of the health issues, but also because of the positions of the corporations and how those relate to our political values’. This may have been a reference to a 1990 gay community boycott of Philip Morris in protest of the company’s support of Senator Jesse Helms, a leading opponent of AIDS funding and LGBT rights (Offen et al. 2003). This boycott popularised the idea that tobacco companies were allied politically with enemies of the community. These leaders suggested a fundamental incompatibility between the values of their organisations and those of the industry. Concern about health was the starting point, reinforced by political considerations.

Other respondents were motivated both by personal conviction and protecting the organisation’s image. One film festival director explained, ‘Other than our own personal beliefs, we also did feel it would…have a negative public relations effect on us, that especially the lesbian community would be very disappointed in us if we accepted a tobacco sponsor’. She added, ‘The lesbian community is particularly hit by cancer although it’s not necessarily lung cancer’. Being motivated by these multiple concerns may have reinforced this leader’s resolve against tobacco funding. Others were also concerned about the opinions of their constituents, but primarily prompted by health concerns for the community. A faith group leader explained that all organisational events were non-smoking due to ‘member concerns, people who either had health concerns or allergies to smoking, asking that they not have to be exposed to smoke’. Members had made their wishes explicitly known. Sometimes feedback for policy decisions came from the larger community. When a pride festival organisation was honoured by a group of LGBT physicians for its policy of not accepting money from the tobacco industry, the director said, ‘It was really good for me to hear that it was appreciated, even outside of our own organisation’. She was pleased to be singled out as a role model for other LGBT leaders.

Some leaders saw tobacco as uniquely harmful. For them, the decision not to accept tobacco money did not lead to a ‘slippery slope’ of constant judgement calls. The director of a film festival with a ‘no tobacco money’ policy described her board’s discussion: ‘We do accept alcohol money…Alcohol can be used responsibly…with tobacco…there’s just no redeeming factor whatsoever’. In addition to singling out the product, this leader singled out the industry: ‘The tobacco industry itself is evil…We wanted absolutely no affiliation with…tobacco… There’s no way we could justify it’. She believed there could be ‘questionable ethics’ attached to other corporate money but felt that tobacco was a ‘clear-cut case’.

The head of an AIDS-related organisation with a written policy prohibiting tobacco money bemoaned the fact that his organisation was financially supported by just one industry, pharmaceuticals. However, his desire to diversify did not extend to the tobacco industry: ‘Part of our mission is to promote health, so it would be really hypocritical for us…to be selling cigarettes’. The desire to be consistent and authentic took precedence over potential revenue. In addition, he expressed the view that taking tobacco industry money would equate to his organisation ‘selling cigarettes’, a perspective in sharp contrast with many leaders of organisations that accepted tobacco funding.

Study limitations

Some participants were unfamiliar with their group’s history with the tobacco industry; in three instances, interviewees reported no industry ties, contradicting other evidence such as news coverage of industry donations to their organisations. In these cases, we report participants’ responses as provided; thus, our findings under-report the full extent of industry financial ties to LGBT organisations. We introduced ourselves as tobacco-control researchers, which may have influenced leaders’ responses. At the time of the study, there were few prominent bisexual or transgender organisations, thus preventing us from obtaining findings specific to these populations; one leader identified himself as transgender and none identified as bisexual. The non-random sample was chosen partially on the basis of the researchers’ and advisory board’s awareness of the groups and does not permit statistical generalisation; however, to our knowledge this is the only study of LGBT organisational leadership to date that addresses tobacco issues.

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest several reasons why tobacco control is not a priority for most LGBT community leaders. Many saw tobacco control as peripheral to their missions. The fact that tobacco-related disease is not unique to the LGBT community played a role in leaders’ demotion of the issue. Many considered their priority to be addressing issues arising directly or exclusively from homophobia or gay identity. This perspective meant that many leaders were reluctant to take up tobacco control and willing to accept tobacco industry money. Although the actions of the tobacco industry were frequently regarded as morally questionable, leaders who accepted industry funding regarded it as necessary for their work. Despite calling it ‘bribery’ or ‘blood money’, leaders felt the funding enabled them to fulfil their primary organisational functions.

The normalisation of tobacco use and the tobacco industry, combined with the perception that tobacco issues fell outside LGBT organisations’ purview, made refusing tobacco money problematic. Many leaders did not see the tobacco industry as either ‘anti-gay’ or illegal. Thus the justification for rejecting tobacco money was unclear, raising the concern that such action would compel them to justify all sources of income, using an externally imposed value-system. Becoming ‘moral police’ might require overwhelming amounts of time and energy and violate community values of acceptance and inclusion.

However, despite this reluctance to judge the industry, leaders were equally reluctant to be associated with promoting it or its products. Even editors who accepted cigarette advertising denied that this was ‘endorsement’, but rather saw it as offering ‘choice’ or ‘information’. However, LGBT periodicals devote little attention to tobacco and disease (Smith et al. 2005, 2006), which undercuts this claim to neutrality.

Leaders’ perception of tobacco use as an individual activity positioned the issue outside their realm of responsibility. These organisations were primarily focused on changing systems or institutions or creating community resources or events. They did not address issues on an individual level. From these leaders’ perspective, tobacco-related disease was too diffuse a problem for them to address; they had no realistic ‘solutions’ to offer. Focus on the individual diverted leaders’ attention from the tobacco industry as an external source of the problem. Rather, tobacco-control issues were seen as dividing the community into ‘smokers’ and ‘non-smokers’. The idea that problematizing smoking was exclusionary or judgemental may have discouraged their adoption of tobacco as an LGBT issue.

Many other issues not exclusive to the LGBT community, such as drug and alcohol abuse, were regarded as more important than tobacco. This perception was partly due to the erroneous belief that alcohol abuse caused more fatalities. In fact, tobacco kills more people than alcohol, AIDS, cocaine, heroin, fire, automobile accidents, homicide and suicide combined (Warner 1989). The higher visibility of drug and alcohol abuse also contributed to this notion; tobacco kills slowly, while the consequences of drunk driving and unsafe sex are often more immediate.

These findings suggest that giving tobacco control ‘master status’ within the LGBT community may be crucial in persuading leaders to adopt the issue. Leaders who saw tobacco control as integral to their role of protecting the well-being of the community were inclined to advocate for it. Those who defined their master statuses through traditionally and exclusively LGBT-focused issues (e.g. gay bashing, LGBT civil rights) tended to feel that their core missions had no room for tobacco control — or might even be harmed by embracing it. When leaders defined tobacco control as external to an organisation’s mission, they also invoked limited carrying capacity, contrasting tobacco issues with the ‘important stuff’ they considered their main priorities.

Redefining tobacco use as a systemic, rather than individual, problem will also be important. Despite efforts of tobacco-control advocates to frame the tobacco issue around the industry’s role as a ‘vector’ of disease, the rhetoric of ‘choice’ and ‘freedom’ was salient to LGBT leaders. Stone’s (1989) contention, that issues are taken up when they are perceived to be responsive to human solutions, helps explain the positions of leaders about accepting tobacco money. Those who refused funding believed that the tobacco industry bore responsibility for tobacco-related disease. They also held themselves accountable: that is, they believed association with the industry contributed to tobacco promotion. Many who thought it was acceptable to take industry funding saw smoking as inevitable and individual and did not believe their actions contributed to the problem of smoking.

The importance of drama in capturing the attention of a community (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988) may also help explain why tobacco has been ignored. Leaders compared tobacco to issues they perceived as more dramatic, such as AIDS and alcoholism. Because tobacco use is normalised, especially within the LGBT community, it lacks the newsworthiness of a drug epidemic of methamphetamine, for example, or the emergence of a drug-resistant sexually-transmitted disease. As a result, tobacco-related issues have difficulty competing for community attention.

Those leaders who saw tobacco as a relevant issue accepted the industry as a threat because of the disease consequences of smoking and the industry’s political alliances. Leaders who saw the industry as the vector did not fear the slippery slope of moral judgement because they viewed the industry as unique. Others believed the industry had already declared itself to be an enemy of the LGBT community through its political positions; thus, opposition to the industry was inherently an LGBT issue. Also, unlike leaders who accepted tobacco money, they believed that taking tobacco money would make their organisations complicit with the industry.

Conclusions

There is currently a growing LGBT tobacco-control movement in the US (National Association of LGBT Community Centers 2007, National LGBT Tobacco Control Network 2007). This study suggests that advocates should reframe tobacco control as an inherently ‘gay’ issue with the tobacco industry as the vector of the problem. Leaders understood alcohol and drug abuse to be gay issues — unhealthy coping mechanisms for living with the stresses of homophobia. They also understood tobacco use to be part of the coming out process. Advocates should link these ideas, redefining tobacco use as a self-destructive way that LGBTs mitigate psychological stress. This understanding would both encourage adoption of tobacco-control issues and justify rejecting tobacco company money.

Transforming the perception of tobacco from an individual to a systemic issue might be facilitated by referring to the LGBT movement itself. The success of the LGBT movement rests on its redefinition of being gay from a personal issue to a political one. By examining the role of societal institutions in perpetuating homophobia, LGBT activists identified parties responsible for harming the community. They helped gay people see their self-hatred in the context of institutionally-enforced homophobia and mobilised the community to confront it. In a mere two generations, psychiatry, the courts and the church, for example, were forced to take steps to reduce the stigma associated with being LGBT.

With these methods and successes in mind, advocates might emphasise that tobacco use is a systemic problem. To those leaders who saw smoking as a personal choice, advocates might point out how the tobacco industry promotes a highly addictive and deadly product. Awareness of the 2006 racketeering conviction of the major US tobacco companies (Zuckerbrod 2006) might challenge those leaders who stressed the legality of the tobacco industry. Advocates might show how engagement with the industry helps keep smoking normalised and perpetuates the epidemic.

This study revealed misconceptions held by LGBT leaders, for example, that alcohol killed more people than tobacco or that breast cancer killed more lesbians than lung cancer. At least one leader thought the tobacco industry might be an appropriate partner for LGBT youth smoking prevention initiatives (tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programmes are ineffective public relations exercises [Landman et al. 2002]). Exposing these and other myths offers an opportunity. Advocates might address the high rates of smoking among LGBT people and the specific consequences of smoking for different sub-populations of the community, such as the impact of smoking on HIV-positive people (Crothers et al. 2005), the interaction of smoking on hormone replacement therapy (Feldman and Bockting 2003) and the connection between second-hand smoke and breast cancer (Miller 2007), an important lesbian concern (Burnett et al. 1999, Fish and Wilkinson 2003, Case et al. 2004).

Another misconception was the idea that taking on tobacco issues meant marginalizing smokers. Advocates might help leaders realise that helping smokers quit does not mean judging or marginalizing them, but providing a welcome service. More than 70% of smokers wish they did not smoke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2002) and a majority support policies to help them quit, such as clean indoor air ordinances (Spears School of Business — Oklahoma State University 2006). Leaders might appreciate recognizing their power to influence the well-being of both individual and community.

Leadership concerns about financing may also provide a way to promote tobacco control. In recent years, funding from the American Legacy Foundation (2007) and other sources has been made available to promote tobacco-control projects in the LGBT community. This support is often contingent on organisational agreement not to accept tobacco industry funding for the period of the grants, policies which often remain in place after the grants expire. Tobacco-control advocates might urge funders to offer more grants that tackle the LGBT tobacco epidemic and encourage LGBT organisations to apply for them.

The LGBT community has not yet identified tobacco use as a gay issue, despite high rates of smoking and particular vulnerabilities to tobacco-caused disease. Many groups and publications are more than willing to accept industry funding and reluctant to prioritise tobacco control. Rejecting funds or taking on tobacco as an issue is perceived to threaten LGBT organisations’ missions. Advocates should help LGBT leaders see that preventing tobacco-caused disease and death is central to their mandates and crucial to the health and well-being of the community they serve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Katherine Thompson and Guadalupe Salazar for assistance in coding transcripts; Teresa Scherzer, Irene Yen and Sue Kim for helpful comments on this paper; and three anonymous reviewers for their excellent suggestions. The research described in this paper was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant #CA90789. Human subjects approval was granted by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

References

- American Legacy Foundation. [accessed 18 May, 2007];Grants Priority Population Initiative. 2007 Available at: http://www.americanlegacy.org/PDF/PriorityPopulations.pdf.

- Baezconde-Garbanati L. Tobacco Education Network; Sacramento, CA: 2003. [accessed 29 August, 2007]. New data shows smoking rates above state average among California’s ethnic and gay and lesbian communities. Available at: www.scienceblog.com/community/older/archives/K/3/pub3380.html. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett CB, Steakley CS, Slack R, Roth J, Lerman C. Patterns of breast cancer screening among lesbians at increased risk for breast cancer. Women & Health. 1999;29:35–55. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bye L, Gruskin E, Greenwood G, Albright V, Krotki K. California Department of Health Services; Sacramento, CA: 2005. [accessed 29 August, 2007]. California lesbians, gays, bisexuals and trans-gender(LGBT)tobacco-usesurvey, 2004. Availableat: http://www.dhs.ca.gov/ps/cdic/tcs/documents/eval/LGBTTobaccoStudy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Case P, Austin SB, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Malspeis S, Willett WC, Spiegelman D. Sexual orientation, health risk factors and physical functioning in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Journal of Women’s Health. 2004;13:1033–1047. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults, United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2002;51:642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crothers K, Griffith TA, McGinnis KA, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Leaf DA, Weissman S, et al. The impact of cigarette smoking on mortality, quality of life and comorbid illness among HIV-positive veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20:1142–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Emilio J. Sexual politics, sexual communities: The making of a homosexual minority in the United States, 1940–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Diamont AL, Wold C, Spritzer K, Gelberg L. Health behaviors, health status and access to use of healthcare. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Wheatley K, Gray R, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years’ observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal. 1994;309:901–911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6959.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J, Bockting W. Transgender health. Minnesota Medicine. 2003;86:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish J, Wilkinson S. Understanding lesbians’ healthcare behaviour: The case of breast self-examination. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:235–245. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood G, Paul J, Pollack L, Binson D, Catania J, Chang J, et al. Tobacco use and cessation among a household-based sample of US urban men who have sex with men. Tobacco Control. 2005;95:145–151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.021451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgartner S, Bosk C. The rise and fall of social problems: A public arena model. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Landman A, Ling P, Glantz S. Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: Protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:917–930. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Tolou-Shams M, Turner L, Dyslin K, Hope B. Elevated risk for tobacco use among men who have sex with men is mediated by demographic and psychosocial variables. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:1197–1208. doi: 10.1080/10826080500514503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Marty MA, Broadwin R, Johnson KC, Salmon AG, Winder B, et al. The association between exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and breast cancer: A review by the California Environmental Protection Agency. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.015. Epub 2006 Oct 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of LGBT Community Centers. [accessed 18 May, 2002];NALG BTCC Member Directory. 2002 Available at: http://www.lgbtcenters.org/lgbttobaccoresearch.htm.

- National Association of LGBT Community Centers. [accessed 17 May 2007];2007 Available at: http://www.lgbtcenters.org/lgbttobaccoresearch.htm.

- National Coalition for GLBT Youth. [date accessed 18 May 2002];Queer America: Find your way. 2002 Available at: http://www.queer-america.com.

- National LGBT Tobacco Control Network. [accessed 17 May, 2007];Filter out Big Tobacco. 2007 Available at: http://www.lgbttobacco.org/index.php.

- Offen N, Smith EA, Malone RE. From adversary to target market: The ACT-UP boycott of Philip Morris. Tobacco Control. 2003;124:203–207. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploderl M, Fartacek R. Suicidality and associated risk factors among lesbian, gay and bisexual compared to heterosexual Austrian adults. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior. 2005;35:661–670. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portugal C, Cruz TB, Espinoza L, Romero M, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Countering tobacco industry sponsorship of Hispanic/Latino organizations through policy adoption: A case study. Health Promotion Practice. 2004;5:S143–S156. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow P, Sullivan WM. Interpretive Social Science: A Second Look. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H, Wortley PM, Easton A, Pederson L, Greenwood G. Smoking among gays, lesbians and bisexuals: A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:142–149. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Malone RE. The outing of Philip Morris: Advertising tobacco to gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:988–993. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. What makes an ad a cigarette ad? Commercial tobacco imagery in the lesbian, gay and bisexual press. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59:1086–1091. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. Pictures worth a thousand words: Non-commercial tobacco content in the lesbian, gay, bisexual press. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11:635–649. doi: 10.1080/10810730600934492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears School of Business, Oklahoma State University. [accessed 29 August, 2007];Oklahoma survey: Most smokers support restrictions. 2006 Available at: http://ssb.okstate.edu/legacyssb/secondary/creator.php?c=./info_pages/news/pr/summer2006/smoking.php.

- Stall R, Wiley J. A comparison of alcohol and drug use patterns of homosexual and heterosexual men: The San Francisco Men’s Health Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1988;22:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(88)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist. 1992;47:6–22. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. Causal stories and the formation of policy agendas. Political Science Quarterly. 1989;104:281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Stone M, Siegel MB. Tobacco industry sponsorship of community-based public health initiatives: Why AIDS and domestic violence organizations accept or refuse funds. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2004;10:511–517. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streitmatter R. Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. Boston: Faber & Faber; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Greenwood GL, Cowling DW, Lloyd JC, Roeseler AG, Bal DG. Cigarette smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals: How serious a problem? Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:798–803. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000043430.32410.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiede H, Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Celentano DD, Ford WL, Hagan H, et al. Regional patterns and correlates of substance use among young men who have sex with men in seven US urban areas. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1915–1921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States of America v. Philip Morris, Inc. et. [accessed 7 December 2007];United States District Court for the District of Columbia. 2006 Available at: http://www.usdoj.gov/civil/cases/tobacco2/amended%20opinion.pdf.

- Warner KE. Implications of a nicotine-free society. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1989;1:359–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yach D, Bettcher D. Globalisation of tobacco industry influence and new global responses. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:206–216. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: Smoking with the enemy. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:336–345. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]