SYNOPSIS

Objective

Long-haul truck drivers and their commercial sex contacts (CCs) have been associated with the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the developing world. However, there is a paucity of information about the STI risk behaviors of these populations in the U.S. We conducted a qualitative phase of a two-phase study to gather information about STI-related risk behaviors in drivers and their CCs in New Mexico.

Methods

Between July and September 2004, we conducted face-to-face unstructured and semistructured qualitative interviews at trucking venues, health department facilities, and a community-based organization to solicit information on sexual behavior and condom and illicit drug use. The interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, reviewed for quality control, and then coded and analyzed for emerging themes using NVivo® software.

Results

Thirty-three long-haul truck drivers and 15 CCs completed the interview. The truck drivers were mostly male and non-Hispanic white with a mean age of 41 years. The majority of the CCs were female, the largest percentage was Hispanic, and the mean age was 36 years. Data suggested risky sexual behavior and drug use (i.e., inconsistent condom use, illicit drug use including intravenous drug use, and the exchange of sex for drugs) that could facilitate STI/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis virus transmission. Results also showed a low knowledge about STIs and lack of access to general health care for both populations.

Conclusions

Additional studies are needed to further assess risk and inform the development of prevention interventions and methods to provide STI/HIV and other medical services to these populations.

Long-haul truck drivers and their commercial sex contacts (CCs; women and men with whom they exchange money and/or drugs for sex) have been implicated in the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) along major transportation routes in developing countries.1–11 Results from studies of long-haul truck drivers suggest that they have low HIV/STI knowledge,12 have higher reported rates of STIs,5,12–19 engage in sex with multiple regular and commercial partners while on the road,5,9,18,20–26 report low condom use,12,16,22,23 and engage in illicit drug use.23

There is a paucity of literature on the HIV/STI risk behaviors of the approximately 800,000 to 1.2 million long-haul truck drivers27 and their CCs in the United States. The available literature suggests, however, that truck drivers in the U.S. also engage in risky sexual behavior with regular and commercial contacts28 and report illicit drug use.28,29 Further, in a qualitative study conducted in Florida,28 truck drivers reported stressful working conditions, lack of access to information about and treatment for HIV and STIs, inconsistent condom use with multiple partners including spouses, and limited access to health care. Few studies have focused on the environment in which sexual exchanges occur between truck drivers and their CCs in the U.S. Additionally, there are no published studies that include both drivers and their CCs.

This article reports results from the qualitative phase of a two-phase, qualitative and quantitative30 study to gather information about STI-related risk behaviors and the environment in which these behaviors occur among long-haul truck drivers and their CCs along major interstate and international trucking routes crossing New Mexico. Data from the qualitative phase were used to inform the development of a quantitative STI risk assessment used in the quantitative and screening phase. Results from the quantitative phase are not included in this article.

METHODS

Participants

Between July and September 2004, study staff conducted face-to-face, anonymous, semistructured and unstructured interviews with long-haul truck drivers and their CCs at trucking venues and health department facilities in Albuquerque, New Mexico. New Mexico Department of Health staff received appropriate training and conducted participant recruitment, interviews, and the consent process.

The truck driver interviews were conducted at a trucking terminal and truck stops, and the CC interviews were conducted at New Mexico AIDS Services, a community-based organization (CBO), and the Stanford Public Health Clinic in Albuquerque. The objectives of the interviews were to (1) solicit information on sexual behavior, as well as condom and illicit drug use to define the environment in which STI/HIV transmission to and from long-haul truck drivers might occur in New Mexico; (2) determine the best sites and methods for recruiting participants into the study; and (3) inform the development of a quantitative instrument for phase two of the study.

Truck drivers were recruited via flyers distributed by study staff at trucking venues and referrals from other truck drivers who participated in the interviews. CCs were recruited from the participating CBO and by referrals from CCs who were in the study. Drivers were eligible for the study if they had a current commercial driver's license and were at least 21 years of age. CCs were eligible if they were at least 18 years of age. We obtained informed consent from the participants prior to the interview, and each participant was compensated $25 for their time and participation. The interviews were approximately 30 minutes long and were audiotaped with consent. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); the New Mexico Department of Health deferred to CDC for this study.

Measures

The study instruments for truck drivers and CCs were developed to meet the phase I objectives for the study and consisted of open-ended questions that solicited demographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, residence, information about typical daily activities, knowledge and history of STIs, sexual behavior (e.g., types and number of sex partners, condom use, venues where sex is sought), best venues including location and time of day for interviewing truck drivers and CCs, and best recruitment strategies for truck drivers and CCs. Additionally, questions related to driving history (e.g., driving status [independent vs. company driver], and driving history [number of years driving, mean number of miles driven per month, and mean number of nights away from home per month]) were included on the instrument for truck drivers, and questions related to length of time exchanging sex for money and/or drugs were included on the instrument for CCs.

Data analysis

The audiotaped interviews were transcribed by the co-principal investigator, transcripts were reviewed for quality control by the principal investigator and co-principal investigator, and appropriate feedback was provided to the interviewers. Following preliminary coding and analysis, the transcripts were imported into NVivo® 7 software for additional coding and analysis.31 Using the constant comparison method for noting emerging themes, three researchers routinely compared and discussed preliminary findings. The constant comparison method provides a systematic framework for data analysis that allows the opportunity to simultaneously analyze multiple transcripts.32–34 We analyzed descriptive data using SPSS® version 10.1.35

RESULTS

Demographics

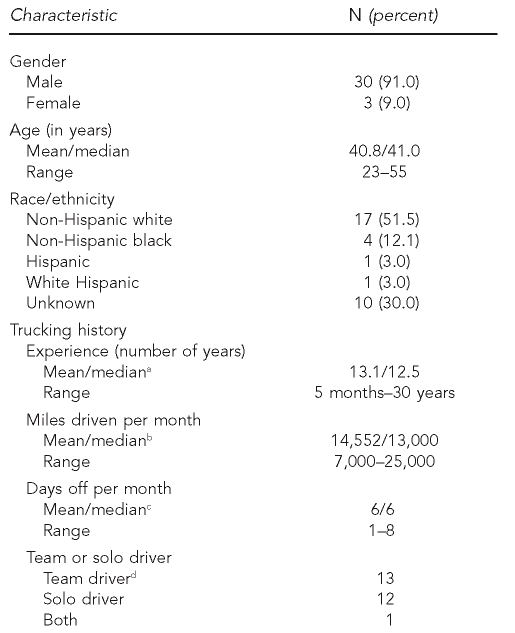

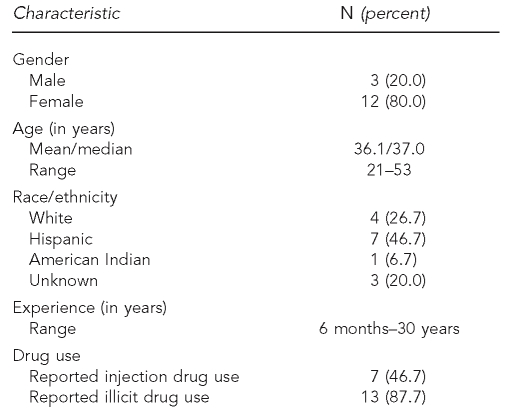

We completed a total of 48 interviews—15 with CCs and 33 with long-haul truck drivers. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the demographics and driving history of the truck drivers, and the demographics for the CCs. The majority of the truck drivers were male (91%) and non-Hispanic white (52%). Their mean age was 41 years, they had been driving a mean of 13 years, and they were off the road (i.e., not driving their trucks) for a mean of six days per month. Conversely, the CCs were mostly female (80%), the largest percentage (47%) reported Hispanic ethnicity, the mean age was 36 years, and they had been working as CCs from six months to 30 years. All reported using illicit drugs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of truck drivers in New Mexico, July through September 2004

aSix truck drivers were unreported (e.g., either refused to answer or answered “do not know”).

bNine truck drivers were unreported (e.g., either refused to answer or answered “do not know”).

cTwelve truck drivers were unreported (e.g., either refused to answer or answered “do not know”).

dSeven truck drivers were unreported (e.g., either refused to answer or answered “do not know”).

Table 2.

Characteristics of commercial sex contacts in New Mexico, July through September 2004

The sections that follow provide results from the qualitative interviews, beginning with a description of how CCs routinely solicit business from long-haul truck drivers. Interviews were not conducted in a systematic fashion. The open-ended interview was designed to allow the interviewer to ask follow up questions based on the respondents' comments. Most interviews captured the themes of the study, but the interviews were not the same from person to person.

We identified several key domains: intravenous and illicit drug use, inconsistent condom use (especially in relation to drug use), the exchange of sex for drugs, increasing demand for male CCs by male truck drivers, limited STI/HIV knowledge, and lack of access to general medical care. An additional domain raised by CCs was exposure to violence. Illustrative quotes from truck drivers and CCs are provided for each of the key domains identified.

Solicitation

CCs described several methods for soliciting truck drivers. The CCs in this study typically arrived at the truck stop around 7 or 8 p.m. and used Citizens' Band (CB) radios to find truck drivers who were interested in “commercial company.” If the truck driver expressed interest, then the truck driver and potential contact would agree to meet on a designated CB channel to discuss specifics of the transaction and designate a meeting location. According to the CCs in the study, sexual interaction usually occurred in the truck driver's cab. After the transaction was completed, CCs would either use that truck driver's CB or knock on other truck drivers' doors to identify additional customers. This process often continued for a few hours; CCs in this study reported up to seven transactions a night. Many spoke of discontentment with their career, but most indicated that this was their only available method of earning money.

Truck stops often hire security in an attempt to protect the site from events such as CC solicitations. However, even with given security arrangements at truck stops, CCs found ways to solicit transactions. They reported having truck drivers pick them up outside of truck stops or driving into truck stops with friends. Additionally, they often used terms such as “commercial company” on the CB to avoid direct identification of sex work, or used CB channels that were less likely to be monitored. For example, when asked, “If there's security at the truck stop, is there a problem and how do you get around it?” one interviewee—a 21-year-old male CC, ethnicity not provided—responded:

Usually there's security at night. I've never had any problem. Usually you go around in a car and act like you're getting gas. Or something is set up ahead and… the women point out likely customers and then I'll go around to them.

Often, CCs reported that they would hang out in restaurants at truck stops and wait for a truck driver to pass by and offer a ride. Other approaches were made at rest areas or casinos frequented by truck drivers. To avoid security entirely, some CCs would only see their regular customers (also called “regulars”), making appointments and specifying meeting locations with them in advance. The contact would be made via cell phone before a truck driver arrived at the location. CCs in the study spoke of having up to 20 regulars who visited at varying times throughout the year. Some maintained a social relationship with their regulars, including dinner or drinks before their interaction. For example, when asked, “Can you tell me about your regulars. How do you make that connection when they come into town?” a 45-year-old Hispanic female CC responded:

They usually tell me what dates they'll come through. I have a calendar and they'll come through and I'll wait for them to call me. And when they do call me, we'll [set up] a meeting place. And when we do get together, we'll go out to eat first because we're more like friends.

CCs also reported that many of their regular truck driver customers have wives or girlfriends—a situation that creates a potential bridge for STIs between the general population and CCs via truck drivers' sexual activity. For example, when asked, “Is it your experience that most of the drivers have families?” a 37-year-old white female CC responded, “Oh yeah, sure, most of them—70% to 80%. They have pictures in their trucks or a wedding ring and they'll tell you.”

In response to questions about the extent and availability of commercial sex throughout the U.S., truck drivers mentioned that CCs were available at truck stops nationwide. As one 43-year-old black male truck driver indicated:

You know, you can get sex anywhere, any city and state. You'll notice that most truck stops are in urban areas, low-income, convenient to truck drivers getting in and out. And they draw all kinds of things. You can buy drugs at a truck stop, you can buy sex, and now they got gay people hanging out, whatever you want to call it—the down low—whatever.

A 52-year-old white male truck driver stated:

I'd say truck stops and rest areas are probably for most people the place to get AIDS. I remember one rest area not too far out of Oklahoma City—they had to close it down because there were too many prostitutes out there all the time, night and day. I stopped there one time about 8 or 9 at night and I was there maybe 35 minutes and there were five different women that came up to my truck.

Intravenous and illicit drug use

The nearly unanimous rationale CCs provided for their occupation was drug addiction, and heroin was the reported drug of choice. Results suggest that the CCs were caught in a situation in which they worked to feed the addiction and used the addiction to complete the work. For example, a 37-year-old white female CC said:

The girls, you know…there are no high-dollar hookers out there at the truck stops. They're usually there, like I said, just for the dope. This is a means of getting it. But other than that, that's just about all that's happening there.

Some participants in the study reported that the drugs of preference for truck drivers were methamphetamine and cocaine. The harsh working conditions were said to promote the use of drugs that allow truck drivers to remain awake and focused for long periods of time. According to CCs, stimulants such as methamphetamine and crack cocaine were used by drivers while driving, with CCs during sex, and during parties. For example, when asked if the truck drivers used any other drugs besides crack, a 30-year-old Hispanic male CC responded:

Mostly crack. But there are methamphetamines there. Once in a while there's heroin, but that's kind of a rarity to the truckers. It's mostly the people that are working that are heroin addicts.

Additionally, one CC discussed being offered drugs in exchange for sex. When asked, “One of the things we are trying to learn about truck drivers is drug use, and we have been told by some other sex workers that drug use is high. Can you tell me what your experience has been with that?” a 45-year-old Hispanic female CC responded, “Yeah, they've come up to me and said they have speed and coke with them sometimes, and they'll even offer that to me instead of money.” Another interviewee was asked, “Out of maybe 10 truck drivers, how many do you think that you come across are using drugs?” The 38-year-old white male CC interviewee answered, “Out of 10, I would guess half. Some smoke pot and all that, but it's mostly crack and crystal meth to stay awake.”

Throughout the interviews, numerous discrepancies arose between responses provided by the truck drivers and the CCs. All of the CCs in the study reported that truck drivers used drugs and paid for sex while on the road. However, none of the 33 truck drivers interviewed reported using CCs or drugs. With regard to drug use, CCs reported that the produce drivers and furniture haulers were drug users because they were often required to wait several days to receive their next load. They were known as the party guys. With regard to CCs, company drivers claimed that the independent drivers used the CCs because they were on the road longer and, therefore, were more often away from home, more lonely, and awake for longer periods of time. Conversely, the company drivers stated that they could be fired if they were caught with a CC. Company drivers also reported that regulations in the industry hindered their use of CCs or drugs. They also reported random drug tests performed by the companies they served. For example, one interviewer asked, “Do you think there is a certain type of driver who is at more risk—by age or type of goods they are hauling—such as independent drivers?” The 24-year-old Hispanic male truck driver responded:

I think the younger drivers because they take more risks generally in everything. I think the independent drivers might take more risks because they own their trucks and can do whatever they want. But if I got caught with a [CC] in my cab or with drugs, I'd lose my license. That's it—I'm out.

Condom use

Study results suggest that condoms were available at most of the major truck stops. For example, when asked, “Are there condoms at the truck stops, in the store only, or are there any in the bathrooms?” a 41-year-old white male truck driver said, “Yeah. You can get them anywhere—vending machines in the restrooms. A lot of truck stops will have machines in the restrooms. You can buy them on the shelves, too.”

However, based on the results, condom use was not necessarily associated with availability in this study. The CCs reported being forced to choose between having sex without a condom and losing a sale. A few CCs said they would leave if a truck driver refused to use a condom; others did not. They discussed the difficulties they often faced. For example, if they chose to walk away, another CC would make himself or herself available to the truck driver and, therefore, the original transaction would be canceled, leaving that individual without money. The CCs in this study reported that most of their truck driver customers preferred to have sex without a condom. For example, in response to the question, “How often do truck drivers refuse to use condoms?” a 53-year-old Hispanic female CC said:

Some of them, they don't like to use a condom and they offer you $200 or $300 more. Some girls take it, but I leave the truck. A lot. Say, like, if I go to 10 different men, say like seven of those guys won't use condoms, so they drop me off and find somebody else. There are lots of young girls—there are girls out there that are 16 or 17—and they think it's a joke and they don't have any condoms. I give them some condoms but they say they don't want to use condoms. “They won't pay me. I'll do what the customer wants.” The young girls have to be educated. They do what the customer wants, and they don't seem to want to take care of themselves.

When asked, “Are you using protection or condoms?” a 30-year-old male CC said:

I'll try to, but not a lot of them want it. With other people, not truck drivers, if I'm getting it—you know, real sex—or if I'm having sex with a woman or a man, then I try to every time I have the chance, but not oral sex. But just because of the desperate lifestyle I live, I guess that's why I don't always do that [use condoms], why a lot of people ignore it.

It's often difficult to turn down a sale, even if it means not using a condom, and the decision about condom use is often left up to the customer. A 24-year-old white female CC stated:

I don't always use protection. They'll call the shots on that. Well, I have them on me. The ones I know that'll use, then I bring them out and everything. But there are some that won't and they just do it and I won't get a sale if I don't do it. And if I really need the money, you know, especially if I'm broke that day and have no other way of getting money, there's no choice.

As previously mentioned, making money and satisfying an addiction were higher priorities for the CCs than protection. When asked, “Do you ever use protection—condoms? Did the issue ever come up?” a 37-year-old white female CC responded:

Not that much. Some of the girls will have condoms and some won't. If you don't have any money and you're out there, you know. .. . Until you do at least one or two tricks you don't have any money. And then when you get your first tricks, that first bit of money is usually gonna go for your dope—you use the money for drugs first. So condoms aren't the first thing on the list, I don't believe. Because you're not gonna say, “Hey, let me stop.” Don't even say, “Hey, let me stop and go get a clean needle,” let alone, “Stop and let me get a condom.”

Nearly every sex worker spoke of being a victim of violence, including rape, burglary, and assault. Many had taken precautionary protective measures such as carrying razor blades or soliciting with a friend to avoid violence or to defend themselves. For example, when asked, “Have you had any close calls yourself?” a 24-year-old white female CC said,

Yeah, I've been raped before. I remember this one time, this guy raped me, took my money, and threw me out of the truck while it was still going. I was pretty laid up in the hospital for that. I guess if I play that game, that's what happens. When I'm not with my regulars, I'm always with another girl or that guy I was with this morning. He helps me out, too.

Use of male CCs among male truck drivers

Three male CCs participated in the interview process. The male CCs in this study made themselves available to both male and female truck drivers. More female CCs were available at truck stops on average, but the presence of males seemed to be increasingly popular. Solicitation styles, however, were quite different. Male CCs did not seek out truck drivers; instead, they were referred by female CCs. Other tactics employed to engage customers for sex work included making eye contact with potential clients at gas pumps and being available in the truck stop restrooms. One male CC described solicitation as follows:

Sometimes, when they blow off a girl, that's pretty much when I know it's a green light for me to make a move as far as soliciting, whatever. That's pretty much the sign I wait for. That's probably one out of every seven to eight truck drivers.

A 21-year-old male CC added, “They [male CCs] go to the truck stop to hang out in case specifically they want a guy. A lot of time they'll pay more for a guy than a girl.”

Lack of access to health care

Both drivers and CCs reported a lack of access to adequate health care. CCs did not have insurance, so their predominant health care was through programs at the health department and the methadone clinic. Conversely, truck drivers tended to be insured, but reported issues related to health-care access due to the mobile nature of their occupation and being away from their approved sources of health care. Even with insurance, it was difficult for truck drivers to make and keep an appointment during business hours. For these reasons, many signs and symptoms of illness or disease would go untreated. A 43-year-old black male truck driver stated:

Insurance for independent drivers and new companies is high for them. They should make some kind of law where insurance is half if you can show you're going to be away from home five days a week. Have some type of program or have it where we can go to a center. If they had good health care they'd probably go. And some of these guys, you know, they might ride a while if they have some type of sexually transmitted disease—they're embarrassed or they don't have the money.

A white female truck driver in her 40s noted, “They have health insurance but can only go to certain people, and that's tough because they only have the weekends off and doctors' offices are usually closed on weekends.”

The CCs also reported problems with health-care access. For example, one interviewer asked, “For the girls who do want to take care of themselves, how do they access medical care or see a doctor? Do they know where to go to get an exam?” A 37-year-old white female CC responded:

I don't know too many of them out there that do. Because when you start going to a doctor, they want blood work; they want to know if you're on drugs… and these are questions that most people… not that they're not comfortable with what they do, but they just don't want to go and get put through that. There are women out there who get abscesses real bad and won't even go to the doctor for that.

Further, in the following interview, a 45-year-old Hispanic female CC spoke of HIV being untreated because of difficulty accessing health care. The interviewer asked, “Is that your access to health care? Do you know if most of the girls are as conscientious as you are about doing those kinds of things—getting checked regularly and using protection?” She responded:

There are some that know that they have AIDS and they don't care. There are some girls, and I've tried to talk to them, and they say, “You're not my preacher.” So I just let them be. If they say they don't have transportation, I'll tell them I'll get them transportation. I'll take you there and stuff like that. Some of them are really off, really out of it, so they don't care. If I know a trucker that goes to them, I won't go to that trucker.”

Some drivers also indicated that they have a general mistrust of the health-care system, particularly in the area of confidentiality and reporting of STIs/HIV. For example, a 40-year-old male driver said:

Once you are diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases, it's going on the World Wide Web… your name is there. Medical people pick it up. They know if you've ever been diagnosed with any of this, and the medical staff is going to prevent the contraception of themselves through the safety they have to take. They get out and talk. Your name is gonna get around some way or another.

Lack of knowledge about STIs/HIV

Responses from some truck drivers indicated a lack of knowledge about STIs. Truck drivers spoke of getting diseases through toilet seats and contact with others who don't clean themselves. For example, a 43-year-old black male truck driver said:

And they ain't gonna tell you they got something. And I ain't gonna be with no woman she ain't putting no water [not taking a bath or shower] on her there. I'm not going to mess with no woman who jumps from one truck and don't put no water on her tail and she goes and gets into the next truck.

Truck drivers in this study also reported lack of exposure to STI literature. One interviewer asked, “What do you think about drivers who are having sex with prostitutes or others on the road—do you think they know about sexually transmitted diseases and whether or not they think they're at risk?” The 43-year-old black male truck driver responded:

They know, but I've heard some of them say, “If I'm gonna die, I'm gonna die happy.” Some do protect themselves but you know the majority of them are pigs, to tell you the truth, and they really don't care. There's no literature in the truck stops telling people about that. I think that'd be a good idea.

In response to the same question, a 41-year-old white male truck driver answered:

We use the XM radio and cell phones to talk with friends. We've never discussed sexual diseases. Well, as for the normal person, they'd probably think the best way to catch it is from a prostitute. You know they're having sex with a lot of people. I wouldn't know about a public restroom or not. You know, if you were to go to a public restroom and sit down on the toilet, because that'd be the place I'd probably catch it.

Most CCs appeared to be knowledgeable about STIs. Many in this study spoke of being tested frequently for STIs and HIV. For example, when an interviewer asked, “If something happens, if you end up coming down with symptoms, how do you take care of that? How do you access care?” a 24-year-old white female CC answered, “I get tested every month.”

Another question addressed a method for improving testing accessibility. The interviewer asked, “Is there a way we can make it easier so that even if people didn't care that much it would be easier for them to fall into it?” A 21-year-old male CC answered, “Yeah, you could do it at the methadone clinic. They do the testing on the spot so you don't have to go anywhere else. Have flyers and pull up the Winnebago across the street.”

DISCUSSION

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to include long-haul truck drivers in the U.S. and their CCs to address the risk environment in which STI/HIV transmission may occur between these populations. These data were collected to inform the development of a follow-up study involving a larger sample, a standardized instrument to collect uniform data, and biological markers for STIs including HIV.

The data reported by CCs are consistent with previous research. They suggest risky sexual behaviors and drug use in these populations that could facilitate STI/HIV transmission. Participants in the study reported multiple and concurrent partners; inconsistent condom use; illicit drug use, including intravenous drug use; and the exchange of sex for drugs. Given the mobile nature of the trucking industry, the fact that most of the truck drivers were married, and CCs reported sex with partners outside and inside the trucking industry, these behaviors could facilitate the spread of STIs/HIV between and among various populations. Results also suggest low knowledge about STIs and lack of access to health care among participants. These factors could exacerbate the problems posed by the risky sexual and drug use behaviors and may further facilitate the acquisition and transmission of STIs/HIV in this population. Individuals who are unaware of how infections are acquired or transmitted and those who have no or low access to health care are often at greatest risk.

Of interest were the discrepancies reported between the CCs and the drivers regarding use of drugs and commercial sex. Although all of the CCs in the study admitted using drugs and soliciting and participating in commercial sex transactions with truck drivers, none of the truck drivers reported the use of CCs or drugs. Truck drivers did, however, report that these behaviors occurred in the industry. Social desirability could be one possible explanation for these discrepancies. Although the interviews were anonymous, they were conducted in the presence of study staff. Additionally, as mentioned by some truck drivers in the study, regulations regarding drug use in the trucking industry could serve as a deterrent for some truck drivers. Truck drivers discussed routine drug screening and penalties for drug use, including loss of licenses, while driving. Further, these discrepancies could also be attributable to the population recruited for the study. Participation was voluntary, and it is possible that those drivers who volunteered for the study were less likely to use drugs or CCs than those who did not. Finally, truck drivers and CCs were not asked specific questions about individual drug use. Therefore, it may have been more difficult for truck drivers to admit to these behaviors of their own volition.

Another interesting finding is related to the availability of STI/HIV educational materials for truck drivers. Some truck drivers in the study reported a lack of these materials at trucking venues. Others stated they were not exposed to STI/HIV public health messages because they often listened to satellite rather than regular radio stations. This finding is important and suggests an area for intervention given the apparent low knowledge of STIs/HIV expressed by the study population.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. As previously mentioned, participation in the study was voluntary, and there may be differences between truck drivers and CCs who volunteered to participate in the study and those who did not. Additionally, the study population was limited to truck drivers and CCs traveling through New Mexico. Therefore, results are not generalizable to truck drivers or CCs across the U.S.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds to the body of literature on the sexual and drug use behaviors of truck drivers and their CCs in the U.S. Based on the results, new areas for intervention may include providing STI/HIV educational materials to truck drivers at trucking venues and exploring avenues for improving access to heath-care services for both truck drivers and CCs. However, additional studies are needed to further assess risk and inform the development of prevention interventions.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karim QA, Karim SS, Soldan K, Zondi M. Reducing the risk of HIV infection among South African sex workers: socioeconomic and gender barriers. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1521–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.11.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Benziger TJ. HIV prevention information, motivation, behavioral skills and behavior among truck drivers in Chennai, India. AIDS. 2000;14:756–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200004140-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Benziger TJ. Determinants of HIV risk among Indian truck drivers. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:1413–26. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carswell JW, Lloyd G, Howells J. Prevalence of HIV-1 in east African lorry drivers. AIDS. 1989;3:759–61. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198911000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris CN, Ferguson AG. Sexual and treatment-seeking behaviour for sexually transmitted infection in long-distance transport workers of east Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:242–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.024117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson DJ, Rakwar JP, Richardson BA, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, Bwayo JJ, et al. Decreased incidence of sexually transmitted diseases among trucking company workers in Kenya: results of a behavioural risk-reduction programme. AIDS. 1997;11:903–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podhisita C, Wawer MJ, Pramualratana A, Kanungsukkasem U, McNamara R. Multiple sexual partners and condom use among long-distance truck drivers in Thailand. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:490–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramjee G, Gouws E. Targeting HIV-prevention efforts on truck drivers and sex workers: implications for a decline in the spread of HIV in Southern Africa. South African Medical Research Council Policy Brief No. 3. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh YN, Malaviya AN. Long distance truck drivers in India: HIV infection and their possible role in disseminating HIV into rural areas. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:137–8. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunmola AM. Sexual practices, barriers to condom use and its consistent use among long distance truck drivers in Nigeria. AIDS Care. 2005;17:208–21. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331325699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taketa K, Ikeda S, Suganuma N, Phornphutkul K, Peerakome S, Sitvacharanum K, et al. Differential seroprevalences of hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug users, commercial sex workers and patients with sexually transmitted diseases in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Hepatol Res. 2003;27:6–12. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meda N, Sangare L, Lankoande S, Compaore IP, Catraye J, Sanou PT, et al. The HIV epidemic in Burkina Faso: current status and the knowledge level of the population about AIDS, 1994–1995. Rev Epidemil Sante Publique. 1998;46:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen XS, Yin YP, Gong XD, Liang GJ, Zhang WY, Poumerol G, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among long-distance truck drivers in Tongling, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:304–8. doi: 10.1258/095646206776790141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gawande AV, Vasudeo ND, Zodpey SP, Khandait DW. Sexually transmitted infections in long distance truck drivers. J Comm Dis. 2000;32:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George S, Jacob M, John TJ, Jain MK, Nathan N, Rao PS, et al. A case-control analysis of risk factors in HIV transmission in South India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:290–3. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199703010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibney L, Saquib N, Macaluso M, Hasan KN, Aziz MM, Khan A, et al. STD in Bangladesh's trucking industry: prevalence and risk factors. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:31–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lankoande S, Meda N, Sangare L, Compaore IP, Catraye J, Zan S, et al. [HIV infection in truck drivers in Burkina Faso: a seroprevalence survey] Med Trop (Mars) 1998;58:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manjunath JV, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ. Sexually transmitted diseases and sexual lifestyles of long-distance truck drivers: a clinico-epidemiologic study in south India. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:612–7. doi: 10.1258/09564620260216317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen W, Anderson PB, Speaker R, Vilches JE. Assessment of condom use among Bolivian truck drivers through the lens of social cognitive theory. Health Promot Int. 2007;22:37–43. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhalla S, Somasundaram C, Bhalla V, Singh S. High risk behaviour and various practices of truck drivers regarding HIV/AIDS and STD. Third International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; 2005 Jul 24–27; Rio de Janeiro. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bwayo JJ, Mutere AN, Omari MA, Kreiss JK, Jaoko W, Sekkade-Kigondu C, et al. Long distance truck drivers. 2: knowledge and attitudes concerning sexually transmitted diseases and sexual behaviour. East Afr Med J. 1991;68:714–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bwayo J, Plummer F, Omari M, Mutere A, Moses S, Ndinya-Achola J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection in long-distance truck drivers in east Africa. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1391–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibney L, Saquib N, Metzger J. Behavioral risk factors for STD/HIV transmission in Bangladesh's trucking industry. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1411–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacerda R, Gravato N, McFarland W, Rutherford G, Iskrant K, Stall R, et al. Truck drivers in Brazil: prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, risk behavior and potential for spread of infection. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl 1):S15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramjee G, Karim SS, Sturm AW. Sexually transmitted infections among sex workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:346–9. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao KS, Pilli RD, Rao AS, Chalam PS. Sexual lifestyle of long distance lorry drivers in India: questionnaire survey. Br Med J. 1999;318:162–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Labor (US). Occupational outlook handbook, 2008–09 edition: truck drivers and driver/sales workers. [cited 2006 Dec 10]. Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos246.htm.

- 28.Stratford D, Ellerbrock TV, Akins JK, Hall HL. Highway cowboys, old hands, and Christian truck drivers: risk behavior for human immunodeficiency virus infection among long-haul truck drivers in Florida. Soc Sci Med. 2002;50:737–49. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeoman B. Forbidden science: what can studies of pornography, prostitutes, and seedy truck stops contribute to society? Discover Magazine. 2004 Aug [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valway S, Jenison SA, Keller N, Vega-Hernandez J, Hubbard McCree D. Risk assessment and screening for sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and hepatitis virus among long-distance truck drivers in New Mexico, 2004–2006. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2063–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.QSR International. NVivo® Version 7.0. Melbourne (Australia): QSR International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dey I. Qualitative data analysis: a user-friendly guide for social scientists. New York: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss AC, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glaser BG, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SPSS Inc. SPSS® Version 10.1. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]