SYNOPSIS

Objective

We examined the associations among perceived discrimination, racial/ethnic identification, and emotional distress in newly homeless adolescents.

Methods

We assessed a sample of newly homeless adolescents (n=254) in Los Angeles, California, with measures of perceived discrimination and racial/ethnic identification. We assessed emotional distress using the Brief Symptom Inventory and used multivariate linear regression modeling to gauge the impact of discrimination and racial identity on emotional distress.

Results

Controlling for race and immigration status, gender, and age, young people with a greater sense of ethnic identification experienced less emotional distress. Young people with a history of racial/ethnic discrimination experienced more emotional distress.

Conclusion

Intervention programs that contextualize discrimination and enhance racial/ethnic identification and pride among homeless young people are needed.

Homeless adolescents experience higher levels of mental health problems than other young people.1,2 Factors that have been linked to mental health problems include family conflict,3,4 a history of physical and/or sexual abuse,2,5 and deviant peer groups.5,6 However, these factors account for only some of the differences in mental health problems between housed vs. homeless young people. One overlooked process is the negative impact of perceived discrimination on the mental health of homeless young people. A growing body of literature has demonstrated a negative relationship between discrimination and mental health in racial/ethnic minority populations in the United States, especially among African Americans7–14 and, to a lesser extent, among Latinos10,14–22 and Asian Americans.10,14,21–24

While evidence for the negative impact of self- perceived discrimination on mental health among minority adults has been increasingly well documented, there remains a relative paucity of research on this relationship among adolescent and young adult populations. A few important studies have demonstrated that for African American young people, increased perceived discrimination was related to increased emotional distress.7–11 Similarly, in a small number of studies of Latino and Asian American young people,21,22 perceived discrimination has been associated with emotional distress.

In one of the few studies of multiethnic young people, Fisher and colleagues demonstrated that perceived discrimination was highest among older, African American, and Latino young people. They reported that regardless of ethnicity, increased perception of discrimination was associated with reduced self-esteem.10 In contrast, Phinney and colleagues22 found no significant differences in levels of perceived discrimination when comparing young people of Armenian, Mexican, and Vietnamese origins in the U.S.; yet, regardless of ethnicity, discrimination was associated with emotional distress.

A greater sense of racial/ethnic identity may be able to reduce some of the negative impacts of perceived discrimination for young people of racial/ethnic minority backgrounds.25–28 Racial/ethnic awareness becomes most prominent during adolescence, as young people begin to develop their self-identity.27–30 Developing a positive sense of racial/ethnic identity and pride should be a protective factor for adolescents who experience discrimination based on their racial/ethnic background.21,27,28 The argument is that a strong sense of racial/ethnic identity for adolescents adds to a strong sense of belonging, which in turn serves as a buffer against the negative impact of discrimination.28

Several recent studies using samples of African American adolescents have found evidence to support this hypothesis.7–9 In particular, a greater sense of racial identity was associated with a reduction in the negative association between perceived racial discrimination and increased emotional distress among African American adolescents,8 and increased racial identity was associated with decreased psychological distress among African American young adults.7 Likewise, in a sample of Chinese and Mexican American adolescents, ethnic identity had a protective effect on psychological well-being.21 This hypothesis regarding the protective effects of racial/ethnic identification has yet to be demonstrated in a multiethnic sample, which includes Latino, African American, and mixed-race young people. Moreover, no high-risk minority populations (e.g., homeless young people) have been assessed in this regard, despite the fact that discrimination impacts major life outcomes for such young people, including housing stability over time.31

Discrimination is defined as intolerant behavior to those who are perceived to be different, including harassment that stems from bias and emotional responses such as fear and hate.32 Discrimination is a multidimensional process that includes the source of the discrimination (e.g., police) or actor who engages in the intolerant behavior, and the social status (e.g., race/ethnicity) that is the target of the discrimination or triggers the intolerant behavioral response.10,33,34 This way of conceptualizing discrimination has been adapted from Fisher and colleagues10 and Diaz and Ayala,33 with the specific problems of adolescent homelessness in mind. However, this is not the only way discrimination can be defined and measured.34–37 Adolescents have reported distress associated with instances of perceived racial/ethnic prejudice encountered in educational contexts, and with institutional discrimination in stores and by police. Perceptions of discrimination tend to be higher among racial/ethnic minority adolescents than among European American young people.10,12

We investigated the relationship between perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health in a diverse sample of homeless adolescents, and whether racial/ethnic identity is a protective factor that moderates the relationship. We expected African American, immigrant Latino, U.S.-born Latino, and mixed-race/ethnicity homeless adolescents to be more likely to report perceived racial/ethnic discrimination than European American homeless adolescents.10,12 We expected homeless adolescents who experienced perceived racial/ethnic discrimination to be more likely to report emotional distress.7–10 Finally, we expected homeless adolescents with high racial/ethnic identity to be less likely to report mental health problems.7–9

METHODS

Sample

We recruited a representative sample of homeless adolescents accessing services and frequenting known homeless young people street hangouts in Los Angeles County for a longitudinal investigation of trajectories into homelessness and risk for human immunodeficiency virus. We used three criteria to select participants: (1) aged 12 to 20 years; (2) spending at least two consecutive nights away from home without parent/guardian's permission if younger than age 17, or having been told to leave home if aged 18 to 20 years; and (3) having been away from home for six months or less.

The screening instrument included 15 short items to obscure eligibility criteria. Aside from age, four questions were relevant to assessing eligibility: (1) “Are you currently homeless or not living at home with your parent/guardian?” Only young people who answered “yes” to this question were eligible; (2) “How long in total have you been away from home?” Only young people reporting less than six months were eligible; (3) “Since the first time, how many times have you left home again for two days or more?” Young people reporting at least one such incident were eligible, if the young people reported that this was their first incident of homelessness; and (4) “What is the date you first left home without parent/guardian permission or were told to leave home?” If the answer was more than two days, then that participant was eligible.

For the purpose of the current analysis, we further limited the sample to those reporting their racial/ethnic background as Caucasian, African American, mixed race/ethnicity, or Latino. The resulting sample consisted of 254 newly homeless adolescents. Seven participants who reported Asian American or “other” racial backgrounds were removed due to insufficient sample size. All participants were followed longitudinally for 24 months; however, this analysis used baseline data.

We selected recruitment sites through a systematic process. First, we identified all of the potential recruitment sites for homeless adolescents in Los Angeles County by interviewing line and supervisory staff in agencies that served homeless adolescents throughout the county.38 We identified 30 sites, including 17 shelters and drop-in centers and 13 street hangout sites. Next, we audited the sites at preselected times and days per week during three different week-long time periods. This audit determined the number of homeless adolescents that could be found at each site to develop a representative sampling plan that encompassed the entire geographic region of the county. A more comprehensive description of the sampling strategy has been published elsewhere.39,40

Based on the sampling plan, interviewers were sent out in pairs to screen and recruit eligible homeless adolescents from July 2000 to March 2002. Interviewers screened adolescents using a 15-item screening instrument to determine whether they were eligible to participate in the study. The screening instrument masked the eligibility criteria, confirmed eligibility, and established the length of time the adolescent had been away from home. All newly homeless adolescents who were eligible and agreed to participate were included in the sample. The refusal rate was 9.3%.

Results from overall Chi-square tests examining race/ethnicity, gender, and age showed that those who refused to participate were European American and older adolescents. Participants were assured of confidentiality and the informed consent process was reviewed. Participants were also told that interviewers were required to report current physical or sexual abuse (if younger than 17 years of age) and serious suicidal or homicidal feelings. Following screening, voluntary informed consent was obtained from each adolescent, and informed consent was obtained from people aged 18 years and older. For minors, en loco parentis consent was obtained from a member of the outreach (recruitment) team present, and assent was obtained from the minor. The study fulfilled all human subjects guidelines and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California at Los Angeles.

Procedure

The interviewers received approximately 40 hours of training, which included lectures, role-playing, mock surveys, ethics training, emergency procedures, and technical training. All interviews were conducted face-to-face by trained interviewers using an audiotaped computer-assisted interview schedule that lasted between one and one and a half hours. Paper-and-pencil surveys were used at a few street sites out of necessity. Participants received $20 as compensation for their time spent on the baseline interview.

Measures

We assessed race/ethnicity using two items. The first was, “Which of these would you say is your main racial or ethnic group? White or Caucasian but not Hispanic or Latino; black or African American but not Hispanic or Latino; Hispanic or Latino; American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian/Pacific Islander; mixed race; or other.” In addition, Latino participants were categorized as non-immigrant or immigrant based upon their responses to the question, “Were you born in this country?” Five categories were used for the analysis involving racial/ethnic comparisons: European American, African American, nonimmigrant Latino, immigrant Latino, or mixed race/ethnicity. As noted previously, we excluded from our analyses adolescents indicating that they were American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, or other racial/ethnic group.

We defined racial/ethnic discrimination as being verbally or physically hassled or abused because of one's race/ethnicity. We derived the discrimination measure from Fisher et al.10 and Diaz and colleagues.33 Our adaptation of the discrimination questions combined psychometric testing from previous research with Latino gay men33 and discussions with service providers and other investigators to tailor the items to the experiences of homeless adolescents.

We assessed discrimination using 12 items, each asking, “In the last three months, have you ever been verbally or physically hassled, abused, and/or assaulted because of your race/ethnicity by [source]?” The 12 sources included police, store owners, people you have sex with, drug dealers, gangs, teachers, friends, family, acquaintances, other kids you don't know, other adults, and boyfriend/girlfriend. We used a five-point Likert scale for responses, where 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = most of the time, and 5 = always. Adolescents who responded sometimes, most of the time, or always to any of the 12 items were coded as having experienced discrimination due to their race/ethnicity, while those who responded never or rarely to all 12 questions were coded as not having experienced discrimination. The items were asked for all of the participants regardless of their race/ethnicity.

We measured racial/ethnic identification using two questions: “How important is [your race/ethnicity] to the way you think of yourself?” and “How close do you feel to other people who are [your race/ethnicity]?” Responses to these items were on three- and five-point Likert scales, respectively. The items were rescaled to range from 0 to 4 and summed to create one score (range: 0–8).

We assessed mental health status—the outcome of interest in the analysis—using the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a measure of psychological distress.41 The BSI has been shown to be robust across multiethnic samples.42 Responses on the BSI are on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely for each of the 53 symptoms. We scored the BSI using the Global Severity Index (BSI-GSI), which is calculated as the mean of responses, subsequently ranging from 0–4. The Cronbach alpha for this measure was 0.95 in the sample analyzed. We offered the interview in Spanish for those whose preferred language was Spanish. All items were forward and back translated and, in the case of the BSI, we used the standardized Spanish language version of the assessment.

Data analysis

We constructed a bivariate table to examine the association of racial/ethnic group with the variables of interest. We performed analysis of variance and Chi-square tests to determine whether there were any statistically significant relationships. Then we created a linear regression model, with BSI-GSI as the dependent variable, and racial/ethnic discrimination, racial/ethnic identity, age, gender, and racial/ethnic category as the independent variables. Because of its skewed distribution, the BSI-GSI received a square-root transformation to conform to the normality assumption of ordinary least-squares regression. In estimating predicted values of BSI-GSI based upon this regression, we used the smearing retransformation method of Duan.43 Interactions of perceived discrimination with racial/ethnic group and racial/ethnic identification score were tested in the regression model.

RESULTS

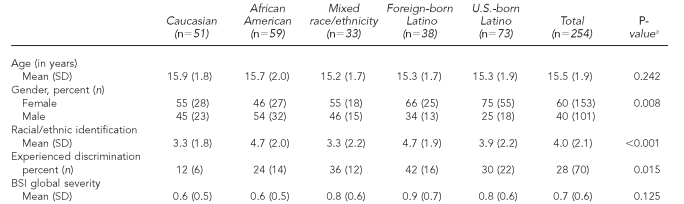

Table 1 shows the characteristics of young people of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. We found no significant difference in age among the groups, but there was a difference by gender (p=0.008), with a higher percentage of females among the two groups of Latinos. There was also a significant difference in racial/ethnic identification (p<0.001). Caucasian and mixed race/ethnicity adolescents had comparably low identification scores, while African American, nonimmigrant, and immigrant Latino adolescents had higher levels of identification. We also found a significant difference (p=0.015) in whether or not adolescents reported having experienced discrimination. Caucasians had the lowest incidence (12%) and foreign-born Latinos had the highest incidence (42%) of discrimination. The BSI-GSI did not differ significantly by racial/ethnic group (p=0.125).

Table 1.

Characteristics of newly homeless young people in Los Angeles County, by race/ethnicity

aAnalysis of variance test for variables expressed as means; Chi-square test for variables expressed as percentages.

SD = standard deviation

BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory

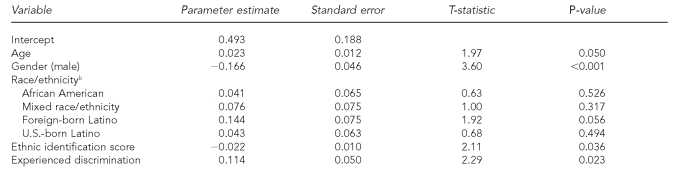

Results of the regression predicting BSI-GSI are shown in Table 2. Terms were inserted in preliminary versions of this model to test whether there was any interaction between race/ethnicity and the experience of discrimination (i.e., whether the impact of perceived discrimination upon BSI-GSI differs by racial/ethnic group). These interaction terms were not significant and were not retained in the model. In addition, an interaction between racial/ethnic identification and perceived discrimination (i.e., whether the impact of perceived discrimination differs by degree of racial/ethnic identification) was also tested, was not found to be significant, and was not retained in the final model.

Table 2.

Linear regression model of newly homeless young people in Los Angeles Countya

aOutcome is square root of Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index.

bReference is Caucasian.

Table 2 shows that age was a significant predictor of psychological distress, with older adolescents reporting greater distress (p=0.05). Gender was also predictive, with females having significantly higher BSI-GSI scores (p<0.001). In this model, which controlled for degree of ethnic identification and the experience of discrimination, racial/ethnic group was not significant. A multiple-partial F-test of the group of racial/ethnic indicator variables did not show a statistically significant impact (p=0.39). Although not significant in this sample, there was a notable trend toward greater distress among the foreign-born Latino group.

The ethnic identification score had a significant negative impact on BSI-GSI (p=0.036), indicating that those with a greater sense of identification experienced less distress. Those who experienced discrimination reported significantly greater distress (p=0.023). To illustrate the impact of these measures, we calculated predicted values of BSI-GSI scores, retransformed to the original (squared) scale. In the case of a 15-year-old U.S.-born Latina female with an ethnic identification score at the sample mean (4), we would expect a BSI-GSI score of 0.74 if she did not report any experience of discrimination, and a score of 0.94 if she did. If this same individual had an ethnic identification score that was roughly one standard deviation above the mean (6), we would expect a BSI-GSI score of 0.66 without any history of discrimination, and a score of 0.86 if there was such a history.

DISCUSSION

Several important findings emerged from this study. First, controlling for race/ethnicity and immigration status among homeless young people, perceptions of discrimination were associated with increased emotional distress. This finding is in keeping with previous studies that have also demonstrated this association in African American,7–10,14 Latino,14,21,22 and Asian American21,22 young people. This finding is important because it is the first time such results have been demonstrated among high-risk young people (i.e., homeless young people in this case) and in a multiethnic sample that included African American, foreign-born Latino, U.S.-born Latino, mixed-race, and Caucasian young people.

Moreover, not surprisingly, all racial/ethnic minority young people reported higher levels of perceived discrimination relative to Caucasian young people. The group that reported the highest levels of perceived discrimination were foreign-born Latinos. With the exception of a few noteworthy studies that have compared Latino and Asian American young people,21,22 relatively few studies have looked at multiethnic samples. Hence, these differences are noteworthy, if intuitive.

Third, higher levels of racial/ethnic identification were likewise associated with lower emotional distress. This finding is consistent with the growing literature on the negative impact of perceived discrimination on emotional distress among racial/ethnic minority adolescents and the protective nature of racial/ethnic identification in moderating this association.7–10 To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate these associations in a population of high-risk adolescents. Moreover, these findings hold for African American, mixed-race, foreign-born Latino, and U.S.-born Latino young people, and expand the base of knowledge regarding this phenomenon into a diverse, multiethnic sample of adolescents.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we only investigated the subjective experiences of discrimination based upon self-reports. However, such experiences have been linked to negative physical and mental health outcomes.37 Also, we only examined one form of discrimination—the relationship of racial/ethnic discrimination with mental health problems. Other forms of discrimination such as gender and sexual orientation may be related to mental health problems. Nonetheless, race has been an important social marker since the inception of the U.S. and has been measured in some form since the 1790 Census.44 Racial/ethnic discrimination is particularly salient35,37,45 and has been widely studied in areas other than mental health.46

Additionally, protective factors such as racial/ethnic identity that may buffer the deleterious consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination could not be examined.8 We only considered the direct relationship of racial/ethnic discrimination to mental health problems and not the possibility that racial/ethnic discrimination can increase mental health problems through its relationship to other risk factors (e.g., family conflict).8 Nonetheless, for African American, U.S.-born Latino, and mixed race/ethnicity adolescents, racial/ethnic discrimination was related to mental health problems, as has been found in previous research, primarily among African American young people.7–10

Second, the study group was a representative sample of young people accessing services and frequenting known homeless young people street hangouts. Young people less well integrated to street culture (e.g., first-time runaways) may be underrepresented in our final sample. This sample may be biased toward young people who are more fully integrated into street culture and, thus, more emotionally distressed.1–5

Third, the measure of ethnic identification used in this article was the sum of only two items and was not as subtle as some other scales, such as the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure.47 The measure we used, however, conforms to the findings of previous literature suggesting that ethnic identification among adolescents has a protective association with respect to emotional distress.7–11,14,21,22

CONCLUSION

Several important implications for future intervention research for high-risk racial/ethnic minority populations, such as homeless young people, emerged from this study. Because racial/ethnic identification reduces emotional distress for minority, homeless young people, mental health programs should be designed for these young people that build on racial/ethnic identification and pride. Because we know from previous work that perceptions of discrimination can impact important outcomes (e.g., housing)31 for these young people, interventions that increase racial/ethnic identification may help protect minority young people from the deleterious effects of discrimination and help them to return to more stable living situations that are more conducive to positive health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Unger JB, Kipke MD, Simon TR, Montgomery SB, Johnson CJ. Homeless youths and young adults in Los Angeles: prevalence of mental health problems and the relationship between mental health and substance abuse disorders. Am J Community Psychol. 1997;25:371–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1024680727864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitbeck LB, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, Cauce AM. Mental disorder and comorbidity among runaway and homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kipke MD, Simon TR, Montgomery SB, Unger JB, Iversen EF. Homeless youth and their exposure to and involvement in violence while living on the streets. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:360–7. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringwalt CL, Greene JM, Robertson MJ. Familial backgrounds and risk behaviors of youth with thrownaway experiences. J Adolesc. 1998;21:241–52. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitbeck LB, Simons RL. Life on the streets: the victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth Soc. 1990;22:108–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinze HJ, Toro PA, Urberg KA. Antisocial behavior and affiliation with deviant peers. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:336–46. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:1079–92. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents' school and socioemotional adjustment. J Pers. 2003;71:1197–232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin KH, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: a multilevel analysis. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:371–93. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29:679–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark R, Coleman AP, Novak JD. Brief report: initial psychometric properties of the everyday discrimination scale in black adolescents. J Adolesc. 2004;27:363–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. Am J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–51. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor J, Turner RJ. Perceived discrimination, social stress, and depression in the transition to adulthood: racial contrasts. Soc Psychol Q. 2002;65:213–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbloom SR, Way N. Experiences of discrimination among African American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth Soc. 2004;35:420–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salgado de Snyder VN. Factors associated with acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among married Mexican immigrant women. Psychol Women Q. 1987;11:475–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codina GE, Montalvo FF. Chicano phenotype and depression. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1994;16:296–306. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuber J, Galea S, Ahern J, Blaney S, Fuller C. The association between multiple domains of discrimination and self-assessed health: a multilevel analysis of Latinos and blacks in four low-income New York City neighborhoods. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1735–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryff CD, Keyes CL, Hughes DL. Status inequalities, perceived discrimination, and eudaimonic well-being: do the challenges of minority life hone purpose and growth? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:275–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araujo BY, Borrell LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2006;28:245–66. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiang L, Yip T, Gonzales-Backen M, Witkow M, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Dev. 2006;77:1338–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phinney JS, Madden T, Santon LJ. Pscyhological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. J Appl Soc Psych. 1998;23:937–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dion KL, Dion KK, Pak AWP. Personality-based hardiness as a buffer for discrimination-related stress in members of Toronto's Chinese community. Can J Behav Sci. 1992;24:517–36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:232–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:318–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 1989;9:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erikson EH. Identity: youth and crisis. New York: WW Norton – Co.; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, Stubben JD. Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:405–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milburn NG, Ayala G, Rice E, Batterham P, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Discrimination and exiting homelessness among homeless adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12:658–72. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewstone M, Rubin M, Willis H. Intergroup bias. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:575–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:927–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1200–3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer IH. Minority and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson IR. Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:97–107. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks R, Milburn NG, Witkin A, Rotheram-Borus MJ. System-of-care for homeless youth: service providers' perspective. Eval Program Plann. 2004;27:443–51. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Batterham P, Brumback B, Rosenthal D, Mallett S. Predictors of close family relationships over one year among homeless young people. J Adolesc. 2005;28:263–75. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witkin AL, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Batterham P, May S, Brooks R. Finding homeless youth: patterns based on geographical area and number of homeless episodes. Youth Soc. 2005;37:62–84. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derogatis LR. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): administration, scoring and procedures manual. 3rd ed. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoe M, Brekke J. Testing the cross-ethnic construct validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory. Res Social Work Practice. 2009;19:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan N. Smearing estimate: a nonparametric retransformation method. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:605–10. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mays VM, Ponce NA, Washington DL, Cochran SD. Classification of race and ethnicity: implications for public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corrigan P, Thompson V, Lambert D, Sangster Y, Noel JG, Campbell J. Predictors of discrimination among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1105–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crosby FJ, Bromley S, Saxe L. Recent unobtrusive studies of black and white discrimination and prejudice: a literature review. Psychol Bull. 1980;87:546–63. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phinney JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: a new scale for use with diverse groups. J Adolesc Res. 1992;7:156–76. [Google Scholar]