Abstract

Background & Aims

Irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by altered sensory qualities, namely discomfort/pain and colorectal hypersensitivity. In mice, we examined the role of P2X3 receptors in colon mechanosensitivity and intracolonic zymosan-produced hypersensitivity, a model of persistent colon hypersensitivity without colon inflammation.

Methods

The visceromotor response (VMR) to colon distension (15 – 60 mmHg) was determined before and after intracolonic saline or zymosan (30 mg/mL, 0.1 mL, daily for 3 days) treatment. Colon pathology and intracolonic ATP release was assessed in parallel experiments. To examine P2X3 receptor contributions to colon mechanosensation and hypersensitivity, electrophysiological experiments were performed using an in vitro colon-pelvic nerve preparation.

Results

VMRs to distension were significantly reduced in P2X3+/−and P2X3−/− mice relative to wildtype mice. Colon hypersensitivity produced by zymosan was virtually absent in P2X3−/− relative to wildtype or P2X3+/− mice. Intralumenal release of the endogenous P2X receptor ligand ATP did not differ between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice or change after intracolonic zymosan treatment. Responses of muscular and muscular-mucosal pelvic nerve afferents to mechanical stretch did not differ between P2X3−/− and wildtype mice. Both muscular and muscular-mucosal afferents in wildtype mice sensitized to application of an inflammatory soup, whereas only muscular-mucosal afferents did so in P2X3−/− mice.

Conclusions

These results suggest differential roles for peripheral and central P2X3 receptors in colon mechanosensory transduction and hypersensitivity.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) afflicts 10%–15% of the population in developed countries.1–3 It is characterized by abdominal discomfort and pain, changes in bowel activity (constipation and/or diarrhea) and colorectal hypersensitivity in the absence of obvious colon pathology. The pathophysiology of IBS is likely multifactorial4 and the mechanism(s) contributing to discomfort and pain remains unclear, which continues to stimulate study of peripheral and central nociceptive mechanisms and mediators of hypersensitivity.

Many experimental models of colon hypersensitivity have been developed, all of which are associated with increases in visceral nociceptive behaviors (replicating the visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients), but most also involve significant inflammatory damage to the colon, which independently may contribute to the increased mechanosensitivity measured. Accordingly, we developed a non-inflammatory model of visceral hypersensitivity in the mouse5 that reproduces these two important features of IBS. Because changes in colonic mechanosensory transduction have been postulated to be partially responsible for IBS discomfort and pain, a variety of molecular targets have been studied. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 (TRPV1)-immunopositive nerve fibers are increased more than three-fold in rectosigmoid biopsies from IBS patients.6 Correspondingly, TRPV1 knockout mice are resistant to development of zymosan-produced colon hypersensitivity.5, 7 Acid-sensing ion channels (ASIC) also have been documented to play a role in gastrointestinal (stomach and colon) mechanosensation,5, 7–9 although evidence for their role in human IBS has yet to be reported. Most recently, TRPV4 has been implicated in colon mechanosensitivity.10

Two endogenous mediators appear to be important in visceral pain and hypersensitivity. Proteases, which are released from the colon in IBS patients, can directly stimulate sensory neurons and generate hypersensitivity through activation of a proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2).11 Adenosine- 5′-triphosphate (ATP), released from intestinal epithelial cells during colon distension, also activates P2X receptors on afferent nerve endings innervating the colon.12–14 In addition, P2X3 receptors are reported to be increased in human colon inflammation.15 However, it is not known whether P2X receptors also contribute to pain and hypersensitivity in non-inflammatory disorders such as IBS, or whether their contribution is peripheral and/or central. In the present study, we examined the role of P2X3 receptors in colon mechanosensory transduction and hypersensitivity in mice using the intracolonic zymosan model that produces hypersensitivity in the absence of colon inflammation. Portions of these data have been reported in abstract form.16

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male mice (20–30 g) of the following strains were used in these experiments: C57BL/6 (Taconic, Germantown, NY) and wildtype, heterozygous and congenic P2X3 knockout (backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 genetic background for ≥10 generations). The genetic status of mice was established by PCR for the P2X3 gene. All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intracolonic Treatments

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (87.5/12.5 mg/kg ip) and either 0.1 mL of vehicle (saline) or of a suspension of 30 mg/mL zymosan (a protein-carbohydrate cell wall derivative of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in saline; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) administered transanally via a 22-gauge, 24-mm-long stainless-steel feeding needle. Intracolonic treatment with saline or zymosan was performed daily for 3 consecutive days after obtaining baseline response measures to colorectal distension (CRD) before assessing colon hypersensitivity.

In some experiments, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (as above) and 0.1 mL of 10 mg/mL 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid (TNBS) (in 50% ethanol; Sigma) was administered transanally as above for zymosan.

Electromyographic Electrode Implantation and CRD Testing

As previously described,5, 17 mice were anesthetized (2% isoflurane; Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL), the left abdominal musculature exposed by incision of the skin, and the bare ends of two lengths of Teflon (DuPont, Wilmington, DE)-coated stainless-steel wire (Cooner Wire Sales, Chatworth, CA) inserted into the abdominal muscles and secured in place with 5–0 polyglactin sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). The other wire ends were tunneled subcutaneously to a small incision made on the nape of the neck and externalized for access during testing. Four days was allowed for recovery from surgery before initiating the CRD protocol.

On the day of testing, mice were briefly sedated with isoflurane for balloon insertion. Distension balloons were made from polyethylene (length, 1.5 cm; diameter, 0.9 cm)18 coated with lubricant, inserted transanally until the proximal end of the balloon was 0.5 cm from the anal verge (total balloon insertion = 2 cm), and secured to the mouse tail with tape. Mice were placed in a restraint device (manufactured as described previously16, 17) inside a sound-attenuating, dark chamber and allowed to recover from isoflurane sedation (30 min) before CRD testing.

Colorectal distension was performed as previously described.17 Briefly, electromyographic (EMG) activity was recorded for 10 sec before and during phasic balloon inflation (15, 30, 45 or 60 mmHg) of the colon. Each distension lasted 10 sec and each pressure was tested three times with 4 min between distensions. EMG electrode activity was amplified, filtered, rectified and quantified using Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design [CED], Cambridge, UK) and recorded on a PC. Responses to CRD were quantified as the total area of EMG activity during balloon inflation minus baseline activity in the 10 sec prior to distension.

Histological Examination of Colon

Mice from intracolonic saline, zymosan and TNBS treatment groups were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (as above) and transcardially perfused with saline followed by a cold fixative (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid dissolved in 0.16 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.9). The colons were removed and immersed in the same fixative for 4 hr at 4°C, then embedded in Tissue Tek (Sakura Finetechnical, Tokyo, Japan), cut in the horizontal plane along the long axis of the colon on a cryostat at a thickness of 10 µm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin and evaluated microscopically.

ATP assay

In other ketamine/xylazine anesthetized mice, the distal colon was exposed and catheterized proximally and distally for controlled distension and perfusion of the lumen to collect and quantify ATP released in saline-, zymosan- or TNBS-treated mice. A 10 mm length of colon was perfused proximal to distal from a reservoir of Krebs solution positioned at various heights to achieve intralumenal pressures of 15, 30, 45 or 60 mmHg when the distal outflow was clamped. As in CRD experiments, each pressure was maintained for 10 sec and applied 3 times at 4 min intervals. The intralumenal perfusate (100 µl) was assayed for ATP using a luciferin-luciferase reagent (100 µl; ATP Bioluminescent Assay Kit, Sigma). Bioluminescence was measured using a luminometer (TD-20/20; Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA) whose detection limit was ~5 fmol ATP/sample. ATP concentrations were extrapolated from a standard-curve.

In Vitro Colon-Pelvic Nerve Electrophysiology

As described previously,7, 19 mice were killed via CO2 inhalation for electrophysiological characterization of pelvic nerve afferent fibers. Briefly, the distal 5–6 cm of colon, mesentery, major pelvic ganglion and pelvic nerves were removed intact, transferred to ice-cold Krebs solution, opened longitudinally along the antimesenteric border and pinned mucosal side up in a Sylgard (Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI)-lined organ bath consisting of two adjacent chambers machined from clear acrylic. The pelvic nerves were extended from the tissue chamber through a small opening into the recording chamber, which was filled with paraffin oil. The colon was superfused with a modified Krebs solution (in µmol/L: 117.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4(H2O)7, 2.5 CaCl2, 11.1 D-Glucose, 2 butyrate, and 20 acetate), bubbled with carbogen (O2 95%/CO2 5%) at a temperature of 33–34°C to which was added the L-type calcium channel antagonist nifedipine (1 µmol/L) and the prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor indomethacin (3 µmol/L). Under a dissecting microscope, the pelvic nerve sheath was gently peeled back to expose the nerve trunk, which was teased into 6–10 bundles using fine forceps. Recordings were made using a platinum recording electrode; an adjacent reference platinum reference electrode was placed in a small pool of Krebs solution. Neural activity was amplified, filtered, sampled at a rate of 20 kHz using a 1401 interface (CED) and stored on a PC. The amplified signal was viewed on-line and also used for audio monitoring.

Mechanosensitive receptive fields were identified by stroking the mucosal surface with a fine brush and then tested with mechanical stimuli to enable classification (serosal, muscular, mucosal and muscular-mucosal) as previously described:19 probing with calibrated von Frey hairs (70 mg - 4 g force), mucosal stroking with calibrated von Frey filaments (10 – 1000 mg force), and circumferential stretch. Custom-built claws were attached at 1mm intervals along the length of the antimesenteric edge of the colon and fixed to a rigid plastic block whose displacement was regulated by a servo-controlled force actuator (series 300B dual mode servo system, Aurora Scientific, Toronto, Canada). This stimulus produced a homogeneous circumferential stretch using a slow ramped force (from 0 to 170mN at 5mN/sec) more closely related to balloon distension and allows mathematical conversion of the circumferential force to intralumenal pressure (Pressure = 2πForce/(LD), where L is colon length and D the circumference). The forces applied convert to pressures between 0 – 45 mmHg distension.

In subsequent experiments in P2X3−/− and wildtype mice, pelvic nerve afferent fiber mechanosensitivity and sensitization after application of inflammatory soup (IS) was tested. The IS consisted of: bradykinin, PGE2, serotonin, and histamine (all at 10mM) with pH adjusted to 6.0.7, 20 A stainless-steel square (4×4 mm; height, 1 cm) was placed over the mechanosensitive receptive field, the Krebs solution removed and IS applied directly to the receptive ending. Inflammatory soup, rather than zymosan,5 was used to evaluate the ability of receptive endings of colon afferents to sensitize; zymosan and IS are similarly effective in sensitizing afferents, but IS is more efficient to apply and wash out. Stretch-sensitive pelvic nerve afferents (muscular and muscular-mucosal groups) were tested before (baseline) and 2 min after application of IS (3 min) to their receptive fields. At least 5 min separated successive ramped stretch of the colon. Data were saved to a PC and analyzed using spike 2 software (CED). Responses to ramped stretch are presented in 15 mmHg bins (0–15, 16–30 and 31–45 mmHg). Response threshold was determined as the force (converted to pressure) that elicited the first action potential; none of the 39 afferent fibers studied were spontaneously active.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Responses to CRD are presented as mean ± SEM percentage EMG activity normalized to 60 mmHg CRD (100%) to generate stimulus-response functions. To compare responses to CRD in wildtype, P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice, total EMG activity is plotted vs. distension pressure. Similarly, to compare the spike numbers to ramped circumferential force in wildtype and P2X3−/− mice after application of IS, spike numbers are normalized by the spike number from the 31–45 mmHg bin (100%) prior to IS application and presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using paired t-tests and 2-way or repeated-measures ANOVAs followed, where appropriate, by Bonferroni-protected post hoc tests; P < 0.05 was set for significance.

Results

Colon Hypersensitivity in Wildtype, P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− Mice

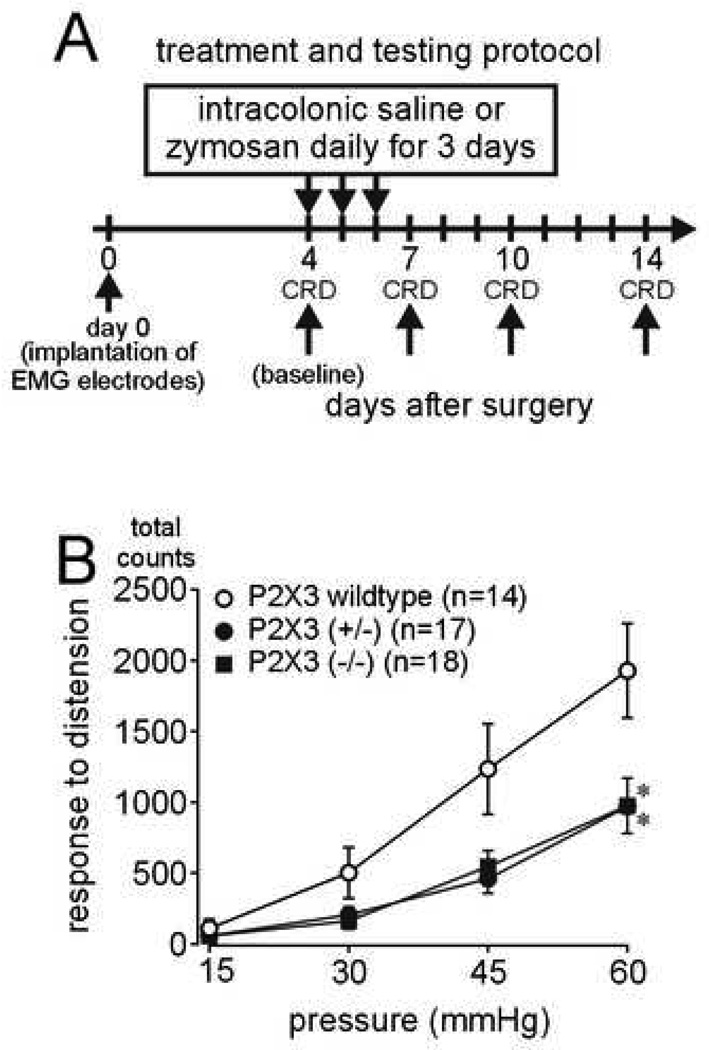

Responses to colon distension were recorded before (day 4; Figure 1A) and after (days 7, 10 and 14) intracolonic administration of saline or zymosan. On day 4 (baseline, before any intracolonic treatment), wildtype, P2X3+/− (heterozygous) and P2X3−/− (homozygous) knockout mice all responded in a graded manner to increasing pressures of colon distension (Figure 1B). However, visceromotor responses to distension in P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice were significantly attenuated relative to wildtype litter mates, revealing decreased mechanosensitivity in these genetically altered mice.

Figure 1.

(A) Treatment and testing protocol. (B) Baseline (day 4) responses to colon distension are significantly less in P2X3+/− (heterozygous) and P2X3−/−(homozygous) null mice relative to P2X3 wildtype mice (F2,200 = 12.82; *P<0.001 compared with P2X3 wildtype mice). Data are expressed as percentage (mean ± SEM) of the visceromotor response to colon distension on the day of baseline testing (day 4) for each animal and normalized to the response to 60mmHg distension (100%) to generate stimulus-response functions.

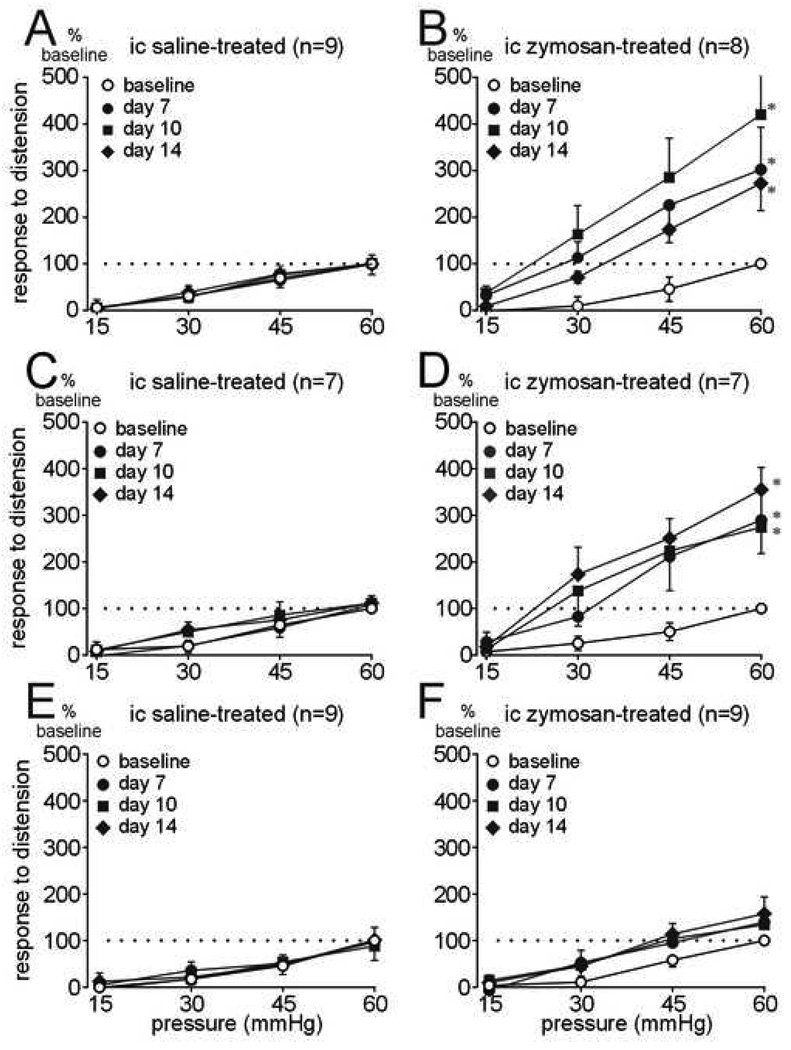

To compare visceromotor responses to distension over time, responses within genetically identical groups of mice are normalized to 60 mmHg in subsequent data presentations. Figure 2A shows that intracolonic saline treatment does not, whereas intracolonic zymosan treatment does (Figure 2B) produce persistent colon hypersensitivity in wildtype litter mate mice. Intracolonic saline treatment had no effect on visceromotor responses to distension in either P2X3+/− or P2X3−/− mice (Figure 2C and 2E). Similar to wildtype mice, intracolonic zymosan treatment in P2X3+/− mice resulted in a significant and persistent colon hypersensitivity (Figure 2D). Despite the difference in response magnitude to colon distension between wildtype and P2X3+/− mice, the relative increase in sensitivity to distension after zymosan treatment was similar (compare Figure 2B with 2D). In contrast, colon hypersensitivity did not develop in P2X3−/− mice after intracolonic treatment with zymosan (Figure 2F), suggesting a role for homomeric P2X3 receptors in processes of colon hypersensitivity.

Figure 2.

(A) Responses to colon distension in P2X3 wildtype mice before (baseline) and after intracolonic (ic) treatment with saline or (B) zymosan (F3,84 = 12.16; *P<0.01 on days 7, 10 and 14 compared with baseline). (C) Responses to colon distension in P2X3+/− mice before (baseline) and after intracolonic (ic) treatment with saline or (D) zymosan (F3,72 = 14.86; P<0.01 on days 7, 10 and 14 compared with baseline). (E) Responses to colon distension in P2X3−/− mice before and after intracolonic (ic) treatment with saline or (F) zymosan. Colon hypersensitivity did not develop in zymosan-treated P2X3−/− mice. Data are expressed as percentage (mean ± SEM) of the visceromotor response to colon distension on the day of baseline testing (day 4) for each animal and normalized to the response to 60mmHg distension (100%) to generate stimulus-response functions.

Colon Histology

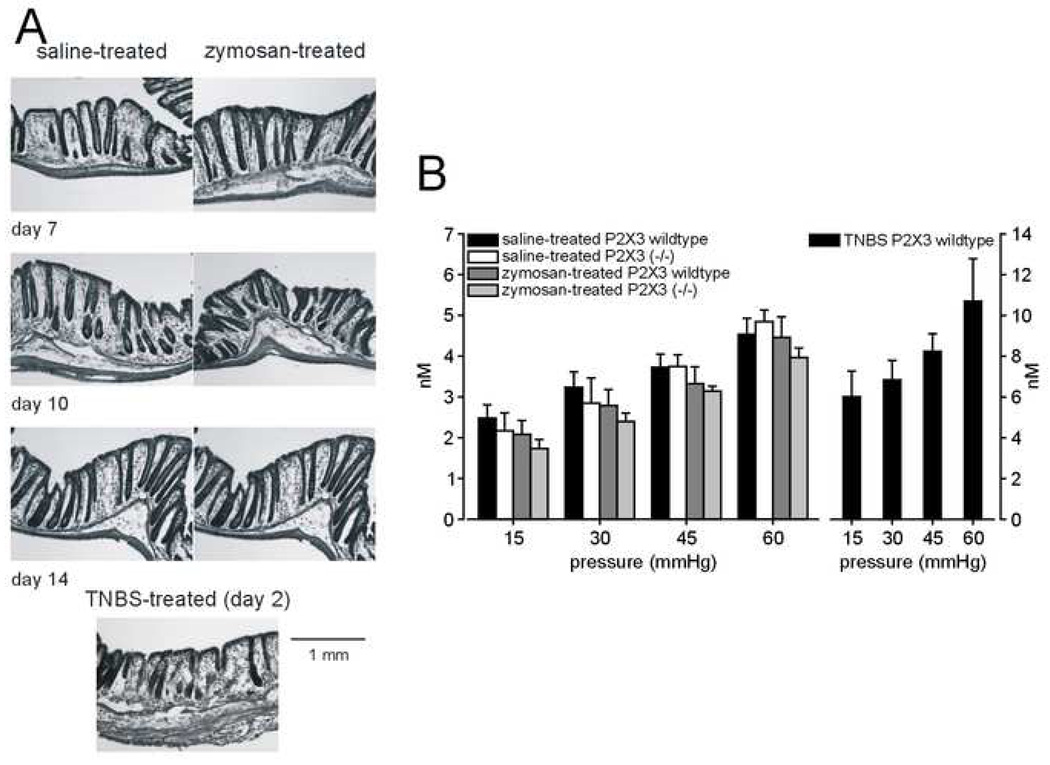

Consistent with previous findings,5 colon hypersensitivity produced by zymosan was not associated with colon inflammation whereas intracolonic TNBS was inflammatory (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Representative histology of mouse colons from saline- and zymosan-treated mice 7, 10 and 14 days after surgical implantation of EMG electrodes. An example of TNBS-produced colon inflammation (2 days after Intracolonic instillation of TNBS) is given for comparison. (B) ATP (nM) released into the lumen of the colon during distension (15, 30, 45 and 60 mmHg, 10 sec) in P2X3 wildtype and P2X3−/− mice after intracolonic treatment with saline or zymosan (left) or TNBS (right; note different vertical scales). ATP release from TNBS-treated P2X3 wildtype mice was significantly greater than from zymosan-treated P2X3 wildtype mice (F3,20 = 6.86; P<0.005). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 6/group.

ATP Release by Colon Distension

Figure 3B (left) shows that the pressure-dependent release of ATP into the colon did not differ between saline-treated wildtype and P2X3−/− mice; further, the intralumenal release of ATP was not increased after intracolonic zymosan treatment in either wildtype or P2X3−/− mice. The intralumenal release of ATP in TNBS-treated wildtype mice, however, was about two-fold greater than in saline or zymosan-treated wildtype mice, confirming that colon inflammation in mice increases ATP release during colon distension as it does in rats (Figure 3B – right).13

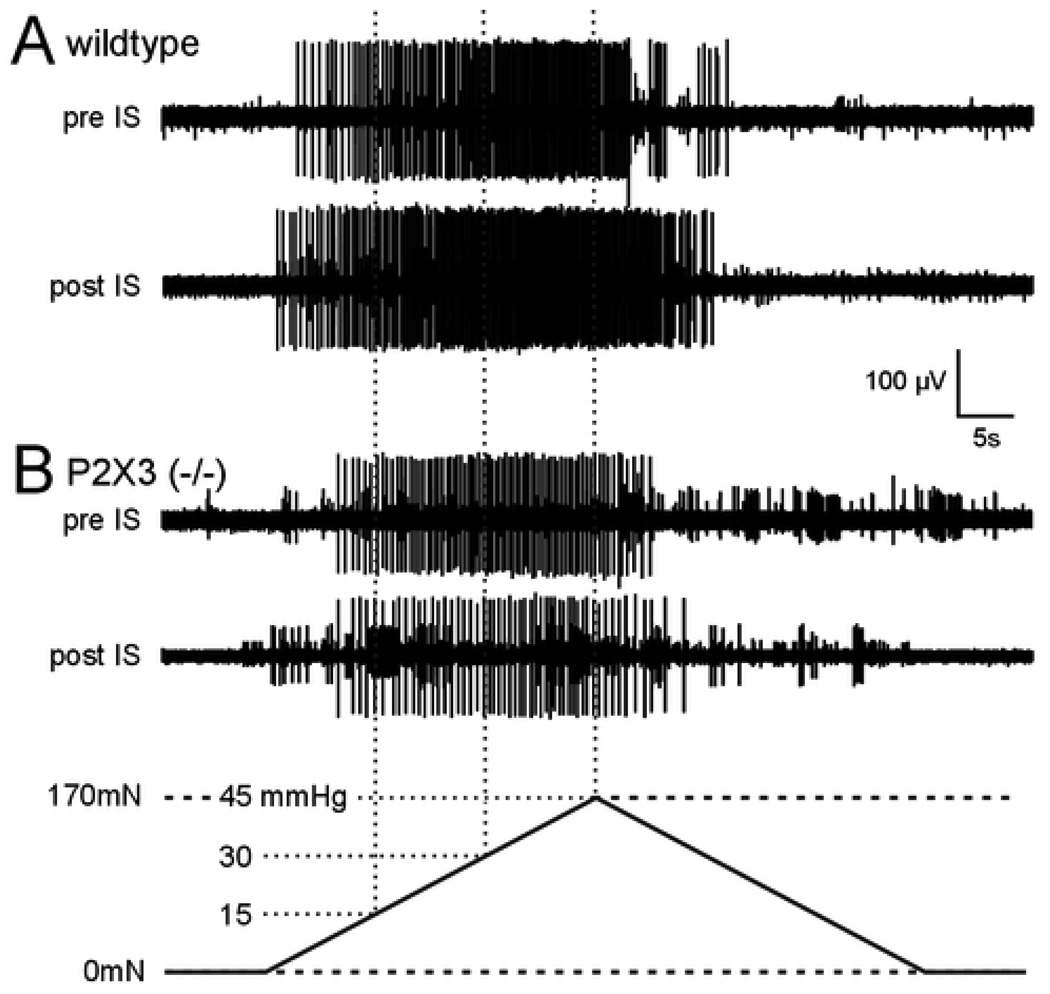

Sensitization of Pelvic Nerve Afferents by IS

Recordings of 39 pelvic nerve afferents that responded to stretch were made in 9 wildtype and 8 P2X3−/− mice (examples are presented in Figure 4). The experimenter was blinded as to mouse genotype while recording and during data-processing. Of the 39 fibers, 8 muscular and 12 muscular-mucosal fibers were recorded from wildtype and 10 and 9, respectively, from P2X3−/− mice. The data are summarized in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Representative examples of responses of two muscular afferents to circumferential stretch before (pre) and 2 min after (post) application of an inflammatory soup (IS). Responses of fibers from wildtype (A) and P2X3−/− (B) mice are shown. Bottom: the circumferential stretch stimulus (5mN/sec force) was applied to the longitudinal edge of the colon preparation. The forces generated translate to intralumenal pressures between 0 and 45 mmHg.

Figure 5.

Responses of muscular (A) and muscular-mucosal (B) afferents to ramped circumferential stretch in wildtype and P2X3−/− mice. Responses to stretch (converted to corresponding pressures) are presented as total number of action potentials in successive bins of 15 mmHg (see Figure 4). There were no significant differences in baseline responses of either fiber type between wildtype and P2X3−/−mice.

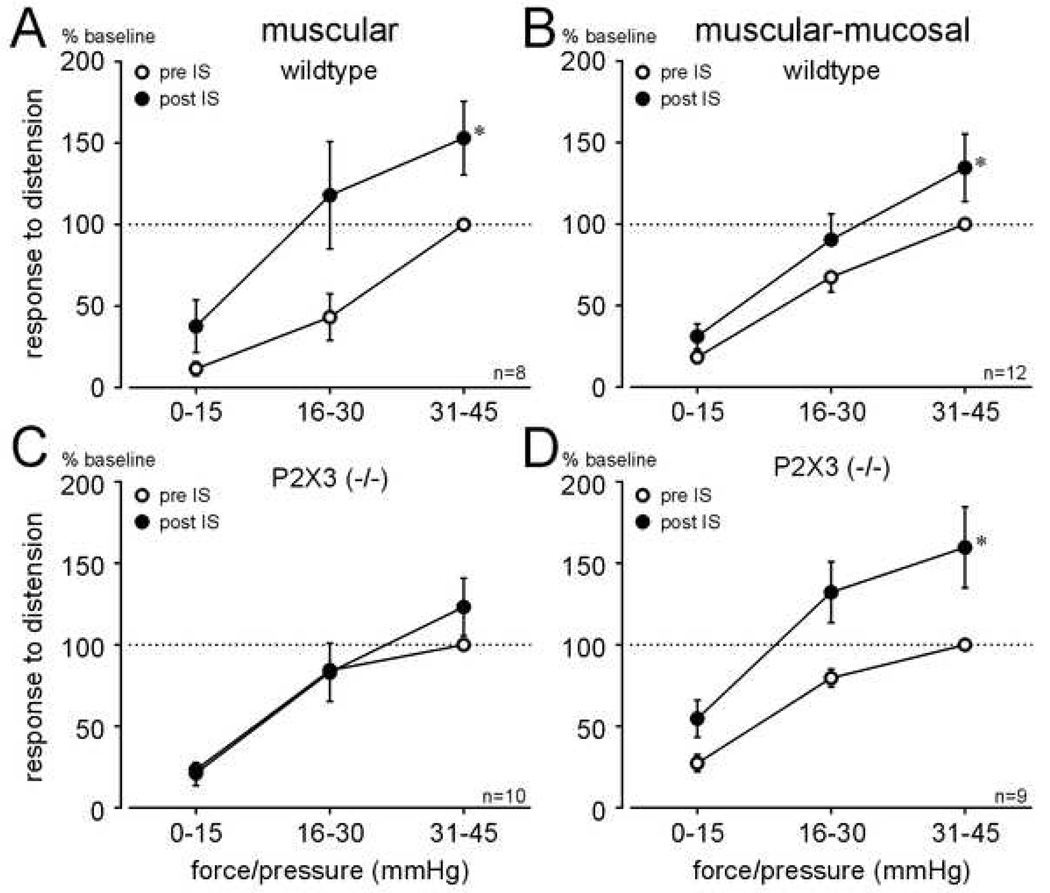

Figure 6.

Responses of muscular (A, C) and muscular-mucosal (B, D) afferents to ramped circumferential stretch in wildtype and P2X3−/− mice before and after application of inflammatory soup (IS) to their receptive endings. Responses to circumferential stretch of both muscular and muscular-mucosal fiber types (presented as in Figure 5) in wildtype mice (A, B) were sensitized by application of IS (A: F1,18 = 10.18; B: F1,33 = 7.71; P<0.01 for both), whereas only muscular-mucosal afferents (D) were sensitized in P2X3−/− mice (F1,24 = 17.91, P<0.001).

Baseline responses to graded forces of ramped circumferential stretch, illustrated as responses to calculated pressures of distension (see Methods), did not significantly differ between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice for either muscular (Figure 5A; F1, 44= 1.41, P>0.05) or muscular-mucosal (Figure 5B; F1, 54= 0.05, P>0.05) pelvic nerve afferents. Figure 6A and B illustrates, for these same fibers, that responses of muscular and muscular-mucosal fibers to stretch in wildtype mice were significantly increased after IS application (i.e., both fiber types were sensitized by IS; (A: F1,18 = 10.18 and B: F1,33 = 7.71, both P<0.01; examples given in Figure 4). In addition, the response threshold, determined as the extrapolated force/pressure that produced the first action potential during stretch (e.g., see Figure 4), of muscular fibers was significantly decreased (P<0.05) in wildtype mice. In contrast, IS failed to sensitize muscular fibers in P2X3−/− mice (Figure 6C). Sensitization of muscular-mucosal fibers to stretch in P2X3−/− mice, however, was produced by IS application as in wildtype mice (F1,24 = 17.91, P<0.001; Figure 6D).

Discussion

The present results reveal peripheral and central roles for ionotropic purinergic P2X3 receptors in colon mechanosensation and colon hypersensitivity. The principal findings are: 1] visceromotor responses to colon distension are significantly (and equally) attenuated in P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice relative to wildtype litter mate control mice, 2] zymosan-produced colon hypersensitivity is robust and persistent in wildtype and P2X3+/− mice, but absent in P2X3−/− mice, 3] muscular and muscular-mucosal afferent fiber responses to circumferential stretch do not differ between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice and 4], stretch-sensitive muscular-mucosal afferents sensitize, whereas muscular afferents do not sensitize in P2X3−/− mice. These findings support important contributions of P2X3 receptors to colon mechanosensitivity and hypersensitivity in the periphery (pelvic nerve) and central nervous system.

The visceromotor response to colon distension is an integrated spinal-bulbospinal response that persists after decerebration (mid-collicular), but is eliminated after either pelvic nerve or spinal cord transection.17, 21 To evaluate peripheral contributions to the results reported here, we recorded directly from afferents innervating the colon, using circumferential stretch to mimic balloon distension of the colon. Mechanosensitive endings in the mouse colon have been characterized in both the lumbar splanchnic and pelvic nerve pathways.19 Two of the five classes of mechanosensitive endings characterized respond to circumferential stretch: muscular and muscular-mucosal. Only 10% of lumbar splanchnic nerve endings respond to stretch (all of which are muscular) whereas 44% of pelvic nerve mechanosensitive endings respond to stretch (about equally divided between muscular and muscular-mucosal endings; the latter are not present in the splanchnic innervation of the colon). We previously documented that reduced baseline visceromotor responses to colon distension were associated in TRPV1 and ASIC3 knockout mice with reduced responses of mechanosensitive pelvic nerve afferents to stretch,7 confirming a peripheral contribution to their reduced visceromotor responses to colon distension. Similarly, TRPV4 knockout mice exhibit reduced responses to colon distension and, using an in vitro nerve-colon preparation as used here, attenuated responses of mechanosensitive endings to probing and circumferential stretch of the colon.10 Accordingly, TRPV and ASIC channels have been directly linked to mechanosensory transduction in colonic afferents and thus underlie, at least in part, behavioral (visceromotor) responses to balloon distension of the colon.

Baseline visceromotor responses to colon distension were reduced to the same extent in P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice, revealing a role for the P2X3 receptor subunit in the reduced mechanosensitivity to colon distension. We hypothesized that P2X3 receptors contributed directly to mechanosensory transduction in the colon (as opposed to, or in addition to a contribution of central P2X3 receptors). However, responses to circumferential stretch (equivalent to 45 mmHg colon distension) of the mechanosensitive endings in mouse colon that respond to stretch (muscular and muscular-mucosal) were found not to differ between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice. Thus, the attenuated visceromotor responses to colon distension in P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice, unlike in TRPV or ASIC knockout mice, are not a reflection of reduced mechanosensory transduction in pelvic nerve colon afferents. Similarly, a recent report failed to find differences in responses of mesenteric afferents to fluid filling of the isolated jejunum between wildtype and P2X2- P2X3 double knockout mice22 which, in concert with the present results, suggests that mouse visceral afferents does not require P2X2 or P2X3 receptors for mechanosensory transduction of distending stimuli.

With respect to colon hypersensitivity, the contribution of P2X3 receptors likely includes a peripheral in addition to a central role. Visceromotor responses in wildtype and P2X3+/− mice were significantly increased throughout the period of testing after zymosan treatment whereas colon hypersensitivity failed to develop in P2X3−/− mice. To address a potential peripheral contribution to colon hypersensitivity, we evaluated the ability of pelvic nerve muscular and muscular-mucosal receptive endings in the colon to sensitize (i.e., to increase response magnitude to stretch) after exposure of the receptive ending to sensitizing mediators. We have previously shown that exposure of mouse pelvic nerve receptive endings to zymosan (a suspension of yeast cell walls) sensitizes stretch responsive receptive endings in the colon.5 Inflammatory soup was used in the present study because its application and termination is more efficient than zymosan and results are qualitatively similar to those produced by zymosan. Consistent with previous work,7 application of IS to colonic muscular or muscular-mucosal endings of wildtype mice in the present study sensitized responses to circumferential stretch As further evidence of sensitization, the response threshold of muscular afferents was significantly reduced by IS. In P2X3−/− mice, responses of muscular-mucosal endings in P2X3−/−mouse colon were sensitized by IS whereas responses of muscular afferent endings to stretch did not sensitize. The interpretation of these results is that colon hypersensitivity is contributed to at least in part by P2X3 receptors associated with stretch-sensitive muscular endings in the colon.

P2X receptors located in the colon have been implicated in mechanosensation and hypersensitivity based on two observations: 1] release of ATP from colon epithelium and 2] activation of colon afferents by ATP. ATP is released from the rat colorectal epithelium in proportion to intralumenal pressure,12, 13 which we replicated in the present study in mice. ATP is also released from epithelial cells during distension of the urinary bladder23, 24 and ureter25 and ATP thus appears to be an important endogenous mediator in visceral sensation. Further, ATP release from rat colon13 and bladder urothelium26, 27 is enhanced after organ inflammation, and greater release of ATP in mouse colon was also documented in the present study following colon inflammation by intracolonic instillation of TNBS. The release of ATP from epithelial cells likely represents a mechanism of indirect signaling with respect to activation and/or sensitization of nearby nerve terminals located in the epithelium and/or sub-epithelium. Consistent with a mechanism of indirect signaling, mRNA encoding P2X3 has been detected in canine colonic circular and longitudinal muscle28 and P2X3 receptor immunoreactive fibers are present in the rat enteric nervous system in the distal colon wall.29 Importantly, the expression of P2X3 receptors has been reported to be increased in human inflammatory bowel disease,15 supporting a role for ATP release and colonic P2X3 receptors in colon mechanosensation and hypersensitivity. However, because neither the amount of ATP released by colon distension nor mechanosensory transduction in mouse colon stretch-sensitive afferents differed between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice (or between wildtype and P2X2-P2X3 double knockout mice22), release of ATP locally appears not to be necessary and sufficient to explain the reduced visceromotor responses to colon distension in P2X3−/− mice.

That local, colonic ATP can activate pelvic nerve afferents12 has been interpreted as supporting a role for P2X receptors in colon mechanosensation. In a previous study 30, we examined responses of serosal endings (which respond to perpendicular probing of the receptive ending, but not to stretch or stroking of the mucosa) in the mouse colon to application of α,β-methylene ATP, a P2X2/3 and 3 receptor-selective agonist. Endings in the splanchnic but not the pelvic innervation of the colon were responsive, suggesting differential sensitivities to ATP of classes of mechanosensitive endings in the two pathways of colon innervation. These and other findings suggest that ATP and other purinergic receptor agonists have the ability to sensitize peripheral nerve terminals to mechanical stimuli. For example, P2X receptor agonists sensitize high-threshold mechanosensitive units in skin12 and P2X receptor activation increases the sensitivity of sensory neurons to heat, an effect abolished after removal of ATP.31 Similarly, α,β-methylene ATP sensitizes mechanoreceptors on vagal afferent fibers in a model of acute esophagitis.32 In the aggregate, it appears that endogenous ATP released during colorectal distension contributes principally to sensitization of mechanically-sensitive receptive endings, an action supported in the present study by the absence of colon hypersensitivity in P2X3−/− mice.

P2X receptors exist in heteromeric and homomeric configurations. The presence of homomeric P2X3 receptors in colon sensory neurons is supported by the observation that the predominant inward current produced by ATP in mouse colon sensory neurons (lumbosacral and thoracolumbar) is a rapidly activating and desensitizing current consistent with a homomeric P2X3 receptor configuration.13 Because mechanosensitivity of pelvic nerve afferents was not different between wildtype and P2X3−/− mice, whereas visceromotor responses to colon distension were significantly attenuated in both P2X3+/− and P2X3−/− mice, P2X3 receptors in either homo- or heteromeric configurations in the pelvic nerve afferent innervation appear not to be required for normal colon mechanosensory transduction. Because responses of muscular afferent endings could not be sensitized in P2X3−/− mice, and colon hypersensitivity does not develop in P2X3−/− mice, muscular afferent endings appear to contribute to development of colon hypersensitivity. The present results thus support the conclusion that central P2X3 receptors contribute to the visceromotor response to colon distension whereas peripheral and central contribuitons of P2X3 receptors are important to colon hypersensitivity.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH award NS 19912. P2X3 knockout mice were graciously provided by D. A. Cockayne, Neurobiology Unit, Roche Bioscience, Palo Alto, USA. We gratefully acknowledge the advice and assistance provided by Lori Birder, University of Pittsburgh, in measuring ATP release into the lumen of the colon and thank Michael Burcham for preparation of the graphics.

Grant Support: NIH award NS 19912

Abbreviations

- ASIC

acid-sensing ion channels

- CRD

colorectal distension

- EMG

electromyography

- IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome

- IS

inflammatory soup

- PAR2

proteinase-activated receptor-2

- TNBS

2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1

- VMR

visceromotor response

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Spiller R. Clinical update: irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2007;369:1586–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilleri M. Mechanisms in IBS: something old, something new, something borrowed. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanson JF. Options for patients with irritable bowel syndrome: contrasting traditional and novel serotonergic therapies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:701–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA, Whitehead WE, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:2120–2137. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast972120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RC, III, Otsuka E, Wagstrom E, Jensen CS, Price MP, Gebhart GF. Short-term sensitization of colon mechanoreceptors is associated with long-term hypersensitivity to colon distention in the mouse. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:184–194. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akbar A, Yiangou Y, Facer P, Walters JR, Anand P, Ghosh S. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1-expressing sensory fibres in irritable bowel syndrome and their correlation with abdominal pain. Gut. 2008;57:923–929. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.138982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones RC, III, Xu L, Gebhart GF. The mechanosensitivity of mouse colon afferent fibers and their sensitization by inflammatory mediators require transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid-sensing ion channel 3. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10981–10989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page AJ, Brierley SM, Martin CM, Price MP, Symonds E, Butler R, Wemmie JA, Blackshaw LA. Different contributions of ASIC channels 1a, 2, and 3 in gastrointestinal mechanosensory function. Gut. 2005;54:1408–1415. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.071084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page AJ, Brierley SM, Martin CM, Hughes PA, Blackshaw LA. Acid sensing ion channels 2 and 3 are required for inhibition of visceral nociceptors by benzamil. Pain. 2007;133:150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brierley SM, Page AJ, Hughes PA, Adam B, Liebregts T, Cooper NJ, Holtmann G, Liedtke W, Blackshaw LA. Selective role for TRPV4 ion channels in visceral sensory pathways. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2059–2069. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cenac N, Andrews CN, Holzhausen M, Chapman K, Cottrell G, ndrade-Gordon P, Steinhoff M, Barbara G, Beck P, Bunnett NW, Sharkey KA, Ferraz JG, Shaffer E, Vergnolle N. Role for protease activity in visceral pain in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:636–647. doi: 10.1172/JCI29255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynn G, Rong W, Xiang Z, Burnstock G. Purinergic mechanisms contribute to mechanosensory transduction in the rat colorectum. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1398–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wynn G, Ma B, Ruan HZ, Burnstock G. Purinergic component of mechanosensory transduction is increased in a rat model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G647–G657. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu GY, Shenoy M, Winston JH, Mittal S, Pasricha PJ. P2X receptor-mediated visceral hyperalgesia in a rat model of chronic visceral hypersensitivity. Gut. 2008;57:1230–1237. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.134221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yiangou Y, Facer P, Baecker PA, Ford AP, Knowles CH, Chan CL, Williams NS, Anand P. ATP-gated ion channel P2X(3) is increased in human inflammatory bowel disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2001;13:365–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2001.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinoda M, Otsuka E, Gebhart GF. Role of P2X receptors in colon hypersensitivity in the mouse. J Pain. 2008;9:P3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamp EH, Jones RC, III, Tillman SR, Gebhart GF. Quantitative assessment and characterization of visceral nociception and hyperalgesia in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G434–G444. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00324.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christianson JA, Gebhart GF. Assessment of colon sensitivity by luminal distension in mice. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2624–2631. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brierley SM, Jones RC, III, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA. Splanchnic and pelvic mechanosensory afferents signal different qualities of colonic stimuli in mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:166–178. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handwerker HO, Kilo S, Reeh PW. Unresponsive afferent nerve fibres in the sural nerve of the rat. J Physiol. 1991;435:229–242. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Colorectal distension as a noxious visceral stimulus: physiologic and pharmacologic characterization of pseudaffective reflexes in the rat. Brain Res. 1988;450:153–169. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rong W, Keating C, Sun B, Dong L, Grundy D. Purinergic contribution to small intestinal afferent hypersensitivity in a murine model of postinfectious bowel disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferguson DR, Kennedy I, Burton TJ. ATP is released from rabbit urinary bladder epithelial cells by hydrostatic pressure changes--a possible sensory mechanism? J Physiol. 1997;505(Pt 2):503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.503bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlaskovska M, Kasakov L, Rong W, Bodin P, Bardini M, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G. P2×3 knock-out mice reveal a major sensory role for urothelially released ATP. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5670–5677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05670.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight GE, Bodin P, De Groat WC, Burnstock G. ATP is released from guinea pig ureter epithelium on distension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F281–F288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00293.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CP, Vemulakonda VM, Kiss S, Boone TB, Somogyi GT. Enhanced ATP release from rat bladder urothelium during chronic bladder inflammation: effect of botulinum toxin A. Neurochem Int. 2005;47:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girard BM, Wolf-Johnston A, Braas KM, Birder LA, May V, Vizzard MA. PACAP-mediated ATP release from rat urothelium and regulation of PACAP/VIP and receptor mRNA in micturition pathways after cyclophosphamide (CYP)-induced cystitis. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;36:310–320. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HK, Ro S, Keef KD, Kim YH, Kim HW, Horowitz B, Sanders KM. Differential expression of P2X-purinoceptor subtypes in circular and longitudinal muscle of canine colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:575–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang Z, Burnstock G. P2X2 and P2X3 purinoceptors in the rat enteric nervous system. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brierley SM, Carter R, Jones W, III, Xu L, Robinson DR, Hicks GA, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA. Differential chemosensory function and receptor expression of splanchnic and pelvic colonic afferents in mice. J Physiol. 2005;567:267–281. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kress M, Guenther S. Role of [Ca2+]i in the ATP-induced heat sensitization process of rat nociceptive neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2612–2619. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page AJ, O'Donnell TA, Blackshaw LA. P2X purinoceptor-induced sensitization of ferret vagal mechanoreceptors in oesophageal inflammation. JPhysiol. 2000;523(Pt 2):403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]