Abstract

Background & Aims

T-cell–mediated hepatitis is a leading cause of acute liver failure; there is no effective treatment and the mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis are obscure. The aim of this study was to investigate the immune-cell signaling pathways involved—specifically the role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)—in T-cell–mediated hepatitis in mice.

Methods

T-cell–mediated hepatitis was induced in mice by injection of concanavalin A (Con A). Mice with myeloid cell-specific and T-cell–specific deletion of STAT3 were generated.

Results

STAT3 was activated in myeloid and T cells following Con A injection. Deletion of STAT3 specifically from myeloid cells exacerbated T-cell hepatitis and induced STAT1-dependent production of a Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ), and to a lesser extent of Th17 cytokines (IL-17 and IL-22), in a STAT1-independent manner. In contrast, deletion of STAT3 in T cells reduced T-cell mediated hepatitis and IL-17 production. Furthermore, deletion of IFN-γ completely abolished Con A-induced T-cell hepatitis whereas deletion of IL-17 slightly but significantly reduced such injury. In vitro experiments indicated that IL-17 promoted liver inflammation but inhibited hepatocyte apoptosis.

Conclusion

Myeloid STAT3 activation inhibits T-cell–mediated hepatitis via suppression of a Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ) in a STAT1-dependent manner whereas STAT3 activation in T cells promotes T-cell hepatitis to a lesser extent, via induction of IL-17. Therefore, activation of STAT3 in myeloid cells could be a novel therapeutic strategy for patients with T-cell hepatitis.

Keywords: STAT3, liver, T-cell hepatitis, myeloid cells, IL-17

Introduction

Viral hepatitis, which affects half a billion people worldwide, is a major cause of chronic liver injury, leading to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatoceullar carcinoma. Although hepatitis viruses themselves are not cytopathogenic and do not kill hepatocytes, T cell-mediated immune responses play central roles in inducing hepatocellular injury during viral infection.1, 2 Moreover, T-cell-mediated liver injury also contributes to the pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis,3 primary biliary cirrhosis,4 alcoholic liver disease,5 hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury6 and allograft rejection.7 In the past two decades, major progress has been made in the understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying T-cell-mediated liver injury through use of a murine model of T-cell hepatitis induced by concanavalin A (Con A).8 Evidence suggests that Con A-induced T-cell hepatitis is initiated and tightly controlled by interactions between multiple cell types, a variety of cytokines, and their downstream signaling pathways.9 Immune cells involved in Con A-induced hepatitis include CD4+ T cells, natural killer T cells,10 Kupffer cells/macrophages,11 neutrophils,12 and eosinophils.13 Natural killer cells do not play a role in this model.10 Of the cytokines, both IFN-γ (Th1 cytokine) and IL-4 (Th2 cytokine) have been shown to play a central role in Con A-induced hepatitis,14, 15 while the role of IL-17 (Th17 cytokine) has been controversial.16, 17 The inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, has also been shown to play an essential role in T-cell hepatitis.18 In contrast, research findings show that IL-6, IL-22, and IL-10 protect against Con A-induced liver injury.15, 16, 19, 20 The effects of many cytokines mentioned above on Con A-induced hepatocelluar injury are mediated, at least in part, by directly targeting activation of various signaling pathways in hepatocytes that control hepatocyte survival and proliferation. For example, activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) by IFN-γ induces hepatocyte apoptosis and cell cycle arrest,15, 21, 22 while activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-22 induces anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidative stress proteins and consequently promotes hepatocyte survival and proliferation.15, 16, 19, 23 Additionally, activation of I kappa B kinases or STAT3 in hepatocytes protects against hepatocyte apoptosis,24-28 while JNK activation in hepatocytes has no effect on Con A-induced hepatitis.29

Although the roles of various signaling pathways in hepatocytes in Con A-induced hepatitis have been extensively investigated, their functions in immune cells in this model have just recently been revealed. For example, while deletion of JNK1/2 in hepatocytes does not yield any effects, deletion of JNK1/2 in hematopoietic cells protects against Con A-induced hepatitis by inhibiting TNF-α production.29 Here, we demonstrated that STAT3 is activated in myeloid linage cells and T cells during Con A-induced hepatitis. To clarify the role of STAT3 in immune cells during T-cell mediated hepatitis, we generated T-cell-specific STAT3 knockout (STAT3T-cell-/-) and myeloid cell-specific STAT3 knockout (STAT3Mye-/-) mice. Our findings suggest that STAT3 in myeloid cells and T cells plays an opposing role in controlling T-cell hepatitis via modulating differentially expression of innate, Th1, and Th17 cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Eight- to 10-week old male mice were used in all studies performed. T-cell specific-STAT3 knockout (STAT3T-cell-/-), myeloid-specific-STAT3 knockout (STAT3Mye-/-), STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/-, and STAT3Mye-/-IL-17-/- mice were described in the supporting materials. For each group, respective littermates were used as wild-type mice. IL-17A-/- mice on a C57BL/6 background were provided generously by Dr. Iwakura of the University of Tokyo. IL-6-/-, IL-10-/-, and IFN-γ-/- mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All animals were housed in a pathogen-free environment and used in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis were performed with t test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for significance using PRISM software (GraphPad). A P-value of less than 0.05 indicated a significant difference between groups.

All other materials and methods are described in the supporting document.

Results

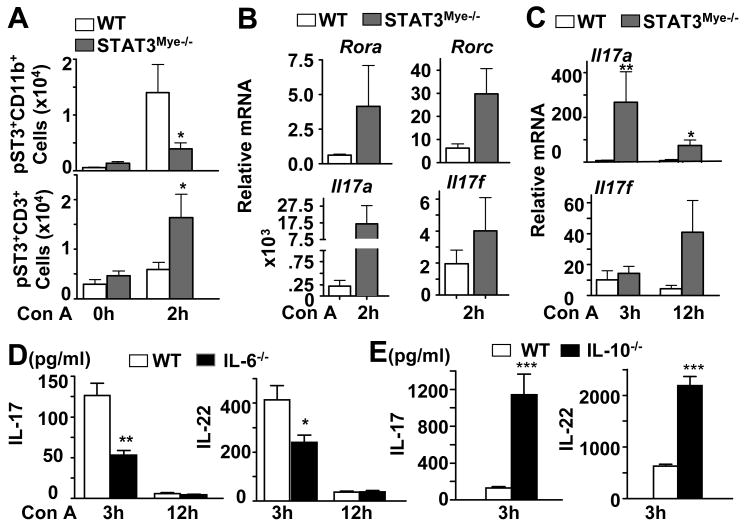

Activation of STAT3 in myeloid cells and T cells during Con A-induced hepatitis

Our previous studies showed that STAT3 and STAT1 were activated in the liver during Con A-induced hepatitis.15 Here we showed by immunostaining that STAT3 activation occurs not only in hepatocytes, but also in virtually all other non-parenchymal cells including inflammatory cells (Fig. 1A). Next, we found that STAT3 and STAT1 were also activated in the spleen after Con A injection (Fig. 1B). Flow cytometry analyses further revealed that STAT3 and STAT1 phosphorylation occurred in CD3+ T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells obtained from the spleen 2 hours after Con A administration (Fig. 1C), which is summarized in Fig. 1D showing that the absolute number of CD11b+ and CD3+ T with activated STAT3 and STAT1 significantly increased after Con A treatment.

Fig. 1. Activation of STAT3 and STAT1 in myeloid and T cells in Con A-induced hepatitis.

C57BL/6 mice were injected with vehicle (saline) or Con A for various time points. A, Phospho-STAT3 immunostaining on liver tissues from control and Con A-treated mice. Blue and red arrows depict pSTAT3 in hepatocytes and small cells in the sinusoids, respectively. B, Western blot analyses of the spleen tissues. C, Flow cytometry analyses of CD11b+ myeloid cells and CD3+ T cells from the spleen of mice treated with Con A for 2 hrs with pSTAT3 or pSTAT1 antibodies. D, Absolute number of CD11b+ and CD3+ cells stained with pSTAT3 or pSTAT1. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

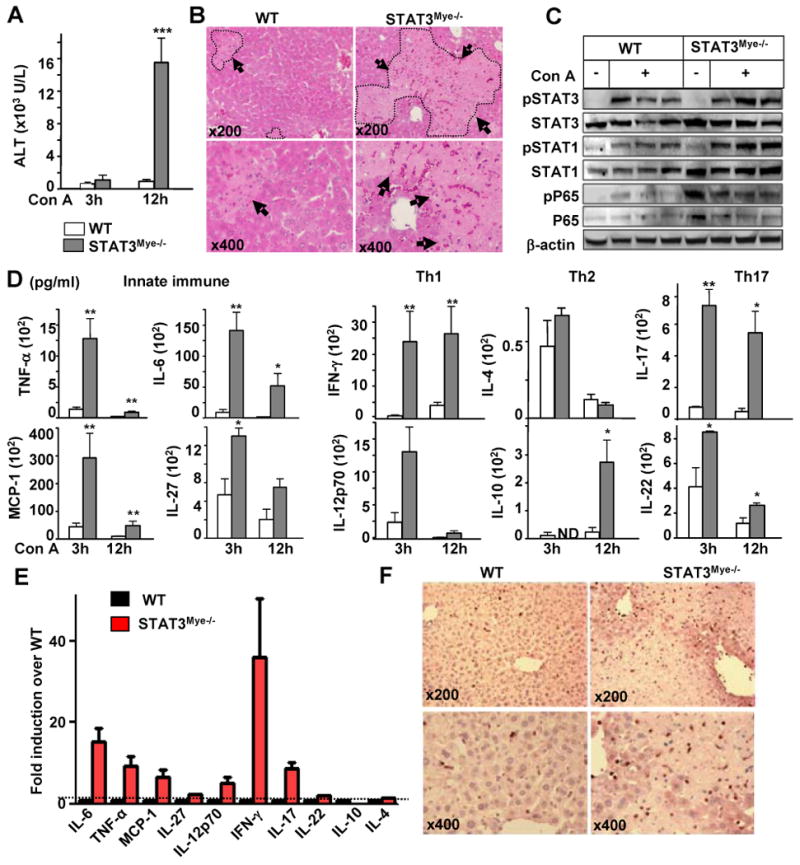

Deletion of myeloid STAT3 enhances preferentially Th1 cytokine response, and Th17 cytokine response to a lesser extent, exacerbating liver injury in Con A-induced hepatitis

To assess the role of STAT3 activation in CD11b+ myeloid cells in Con A-induced hepatitis, we generated myeloid-cell specific STAT3 knockout mice (STAT3Mye-/-). Serum ALT activity and liver histology analyses (Figs. 2A and 2B) revealed that Con A injection induced much greater liver injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice than in wild-type mice. Hepatic expression of pSTAT3, pSTAT1, pNF-κB was higher in STAT3Mye-/- mice than in wild-type mice 3 hours post Con A injection (Fig. 2C). The enhanced hepatic injury observed in STAT3Mye-/- mice was also associated with a marked increase in serum TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-27, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-17, IL-22 (Fig. 2D). Among these cytokines, IFN-γ had the highest induction (about 35 fold), followed by IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, MCP-1, and IL-12p70 (5-10 fold), IL-27 and IL-22 (about 2 fold) (Fig. 2E). Levels of Th2 cytokine IL-4 were comparable between STAT3Mye-/- and wild-type mice. Immunohistochemical analyses of myeloperoxidase (MPO) showed that the number of neutrophils was much greater in the livers of STAT3Mye-/- mice compared with wild-type mice post Con A injection (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2. Myeloid STAT3 depletion exacerbates Con A-induced hepatitis and promotes preferentially innate inflammatory, Th1 (IFN-γ) cytokines and Th17 cytokines to a lesser extent without affecting Th2 (IL-4) cytokine.

A, Serum ALT levels. B, H & E staining of liver sections 12 hrs post Con A injection. Arrows indicate necrotic areas. C, Western blot analyses of liver protein extracts from mice 3 hrs post Con A injection. D, Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines. E, Relative induction of cytokines 2 hrs post Con A injection. The values from wild-type mice were set as 1. F, Myeloperoxidase immunostaining of liver tissues 12 hrs post Con A injection. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.005 (n=5-8), in comparison with the corresponding WT groups. ND for Not Detected.

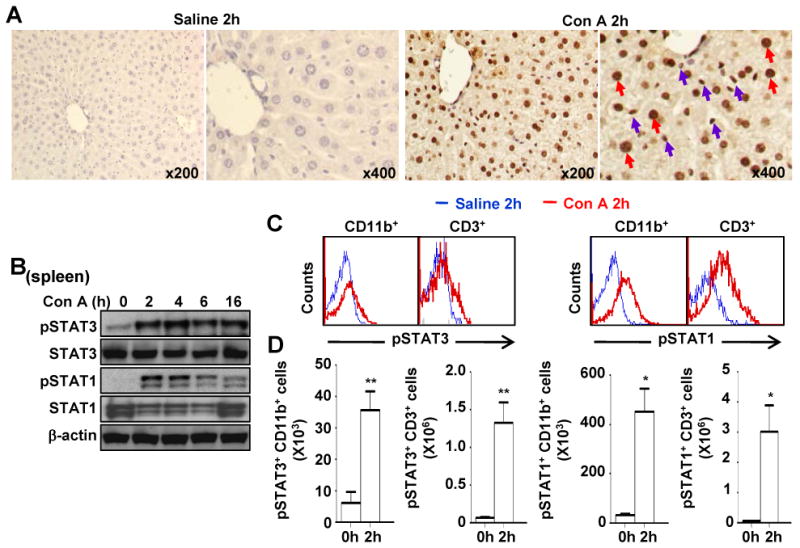

Myeloid-cell specific STAT3 deficiency promotes T-cell STAT3 activation

The inhibitory effect of STAT3 in myeloid cells (such as macrophages) on inflammatory and Th1 cytokines has been well documented;30 however how myeloid STAT3 controls IL-17 response in T-cell hepatitis remains unknown. As STAT3 is required for IL-17 expression in T-cells,31, 32 we analyzed its activation on isolated liver CD3+ T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells 2 hours after Con A administration. As expected, the number of pSTAT3+CD11b+ myeloid cells increased in the livers of wild-type mice, but not in STAT3Mye-/- mice, while pSTAT3+CD3+ T cell accumulation was greater in the livers of STAT3Mye-/- mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 3A). Isolated spleen CD4+ T cells from STAT3Mye-/- mice showed higher levels of Rora and Rorc mRNA (Fig. 3B), encoding for two transcription factors indispensable for IL-17 synthesis.31, 32 Induction of these 2 transcription factors was associated with 70-fold induction of Il17a and 2 fold induction of Il17f mRNA expression in splenic CD4+ T cells from STAT3Mye-/- mice vs. wild-type mice post Con A injection (Fig. 3B). Induction of Il17a and Il17f mRNA expression was also more profound in the livers of STAT3Mye-/- mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). In addition, induction of IL-17 and IL-22 was reduced in IL-6-/- mice, but was enhanced in IL-10-/- mice (Figs. 3D, 3E), suggesting that IL-6 promotes, while IL-10 inhibits, Th17 cytokine production.

Fig. 3. Myeloid-cell specific STAT3 deficiency promotes T-cell STAT3 activation and IL-17 response.

A, STAT3 activation (pSTAT3+ cells) in hepatic CD11b+ and CD3+ T cells 2 hrs post Con A treatment analyzed by flow cytometry. B-C, Real-time PCR analyses of mRNAs from spleen CD4+ T cells (B) and liver tissues (C) of mice treated with Con A. D, E, Serum levels of IL-17 and IL-22. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.005 (n=4-8), in comparison with the corresponding WT groups.

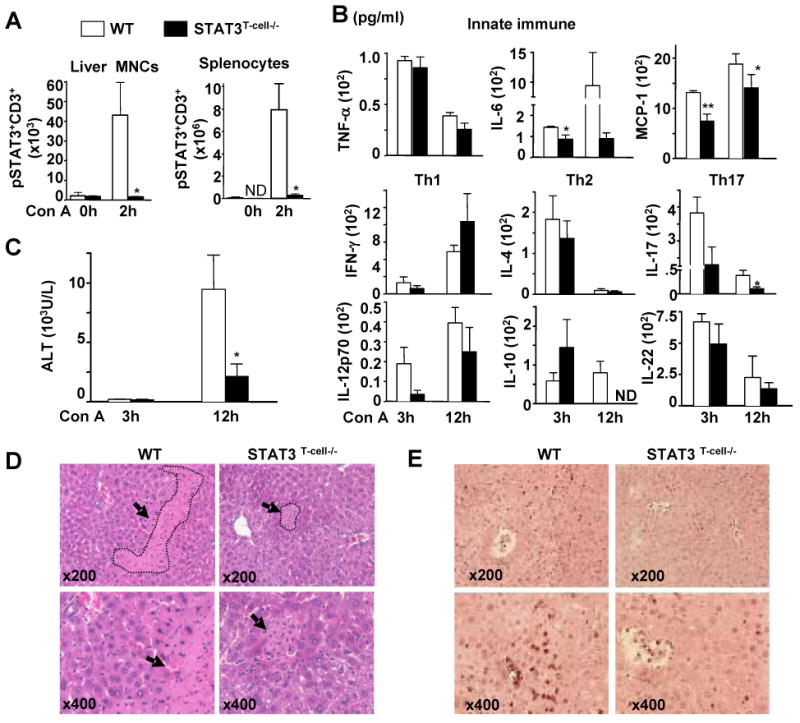

Activation of STAT3 in T cells contributes to the Th17 cytokine IL-17, but not Th1/Th2 cytokine production, and promotes Con A-induced hepatitis

To further define whether STAT3 activation in T cells is responsible for IL-17 production in T-cell hepatitis, we generated T cell specific STAT3 knockout mice (STAT3T-cell-/-). STAT3 depletion in T cells was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 4A). As expected, STAT3 phosphorylation was enhanced in CD3+ T cells from wild-type liver lymphocytes and splenocytes, but was completely abolished in STAT3T-cell-/- mice. Induction of serum IL-17 after Con A injection was markedly diminished (reduced 8-fold) in STAT3T-cell-/- mice, while induction of many other cytokines were comparable between wild-type and STAT3T-cell-/- mice (Fig. 4B). Induction of IL-6 and MCP-1 was slightly reduced in STAT3T-cell-/- mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). Finally, serum ALT activity, liver necrosis, and neutrophil infiltration were lower in STAT3T-cell-/- mice than in wild-type animals 12 hours after Con A administration (Figs. 4C-E). These results suggest that STAT3 activation in T cells promotes Con A-mediated hepatitis.

Fig. 4. Deletion of STAT3 in T cells reduces IL-17 production and liver injury in Con A-induced hepatitis.

A, Phosphorylated STAT3 detection in CD3+ T cells in liver mononuclear cells (MNCs) and splenocytes from mice treated with Con A for 2 hrs by flow cytometry. B, Serum inflammatory cytokines. C, Serum ALT levels. D, Liver tissues stained by Hematoxylin and eosin 12 hrs post Con A injection. Arrows indicate necrotic areas. E, Myeloperoxidase immunostaining of liver tissues 12 hrs post-Con A injection. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (n=6-12). The number of mice used in the all groups in panel B was the same. ND for Not Detected.

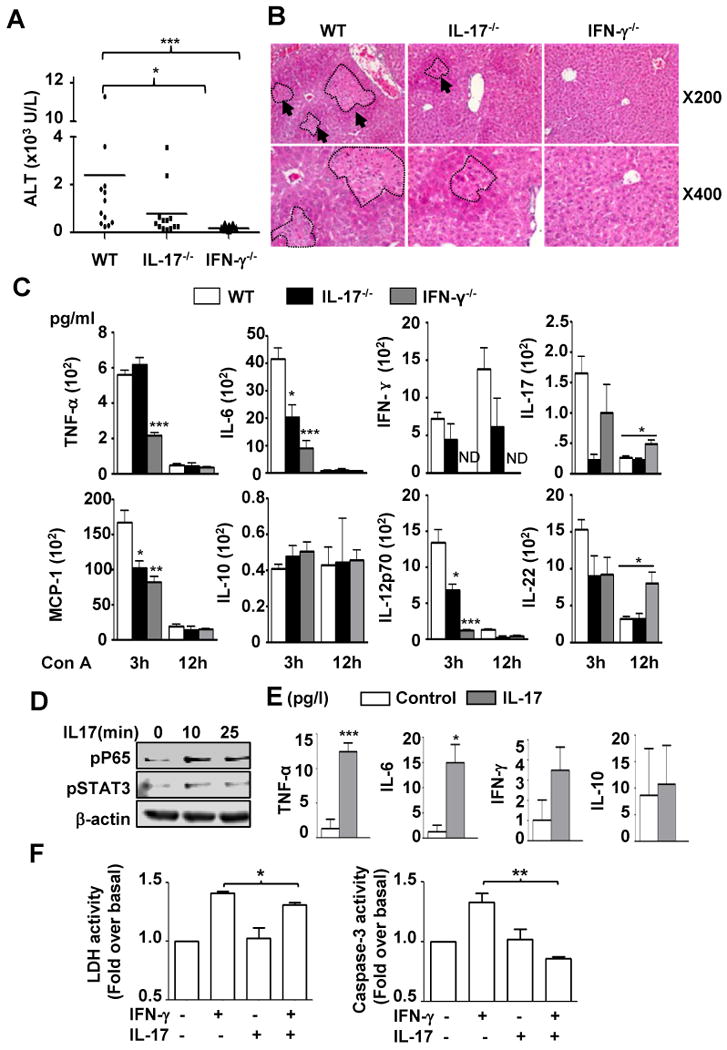

IFN-γ plays an essential role, while IL-17 plays a minor but significant role in T-cell-mediated liver injury

Since both IFN-γ and IL-17 have been shown to play an important role in inducing inflammation,15, 32, 33 we hypothesized that higher levels of IFN-γ and IL-17 may contribute to enhanced liver injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice. To test this hypothesis, we first defined the role of IL-17 and IFN-γ in Con A-induced liver injury by using IL-17-/- and IFN-γ-/- mice, respectively. Histological and biochemical analyses (Figs. 5A-B) revealed a marked reduction (90%) of serum ALT levels in IFN-γ-/- mice compared with wild-type mice, in agreement with earlier findings.15 Unlike the diminished Con A-induced liver injury found in IFN-γ-/- mice, which was very significant and repeatable, the difference in Con A-induced liver injury between wild-type and IL-17-/- mice varied from experiment to experiment. In order to see the true effect, we performed 3 independent experiments (total 12 control mice and 13 IL-17-/- mice), which showed that serum ALT levels were slightly but significantly reduced in IL-17-/- mice post Con A injection compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 5A). Similarly, inflammatory cytokine release was reduced in both IL-17-/- and IFN-γ-/- mice with a stronger inhibition observed in the latter especially for TNF-α and IL-12 (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that both IL-17 and IFN-γ are involved in Con A-induced hepatitis where IFN-γ plays a dominant role in inducing hepatocellular injury.

Fig. 5. IFN-γ plays an essential role, while IL-17 plays a minor but significant role in T-cell-mediated liver injury: IL-17 stimulates Kupffer cells to produce cytokines but prevents IFN-γ-induced hepatocyte apoptosis.

A, Serum ALT levels 12 hrs post Con A injection. B, H & E staining of liver sections 12 hrs post Con A injection. C, Serum inflammatory cytokines. D, Western blot analyses of phospho-P65 and phospho-STAT3 in IL-17-treated liver macrophages. E, Inflammatory cytokines from IL-17-treated liver macrophage culture medium 24 hrs later. F, Isolated hepatocytes were cultured for 3 days without or with IFN-γ (10ng/ml), IL-17 (10ng/ml), or both cytokines. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity and caspase 3 were measured. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. ND for Not Detected.

The proinflammatory effect of IFN-γ in T-cell hepatitis is probably due to activation of STAT1 in various cell types including hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and endothelial cells.34 However, how IL-17 modulates T-cell hepatitis remains unknown. Here we examined the pro-inflammatory effect of IL-17 in liver Kupffer cells. As shown in Figs. 5D and 5E, treatment of liver Kupffer cells with IL-17 induced NF-κB activation and production of TNF-α and IL-6 without affecting IFN-γ and IL-10.

As NF-κB activation in hepatocytes is known as an important key signal in hepatocyte survival,25, 35 we next asked whether in addition to its pro-inflammatory function on macrophages, IL-17 can also modulate IFN-γ-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5F, IL-17 treatment reduced IFN-γ-induced lactate dehydrogenase release and caspase-3 activity in primary hepatocytes. Taken together, these data showed that IL-17 may play a double edged-sword role, by promoting liver inflammation through activation of macrophages, and by protecting hepatocytes from IFN-γ-induced apoptosis.

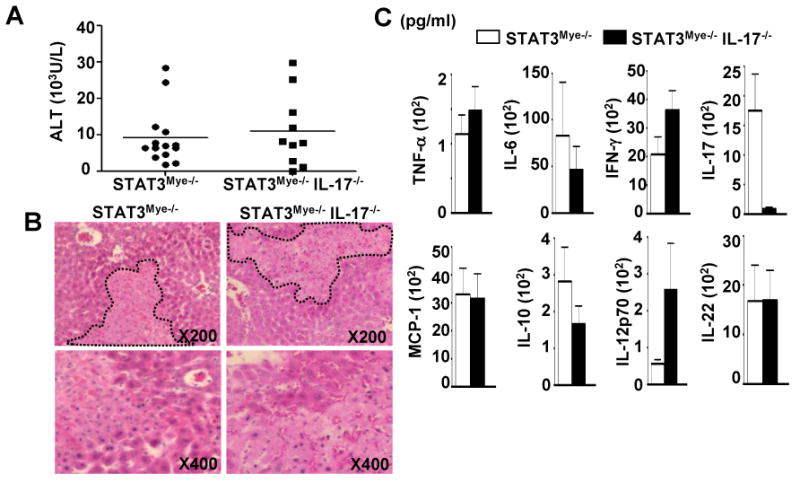

Deletion of IL-17 in STAT3Mye-/- mice does not reduce Con A-induced hepatitis

To further determine the role of IL-17 in liver inflammation and injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice, we generated myeloid-specific STAT3 and IL-17 double knockout mice (STAT3Mye-/-IL-17-/-). Surprisingly, the deletion of IL-17 in STAT3Mye-/- mice did not protect them from Con A-induced liver injury, as shown in Figs. 6A-B by similar levels of serum ALT and liver necrosis compared to STAT3Mye-/- mice. In addition, the high level of the pro-inflammatory cytokine release observed in STAT3Mye-/- mice was not affected in STAT3Mye-/- IL-17-/- double knockout animals (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6. Deletion of IL-17 in STAT3Mye-/- mice does not reduce Con A-induced hepatitis.

A, Serum ALT levels 12 hrs post Con A injection. B, H & E staining of liver sections 12 hrs post Con A injection. C, Serum inflammatory cytokines 12 hrs post Con A injection.

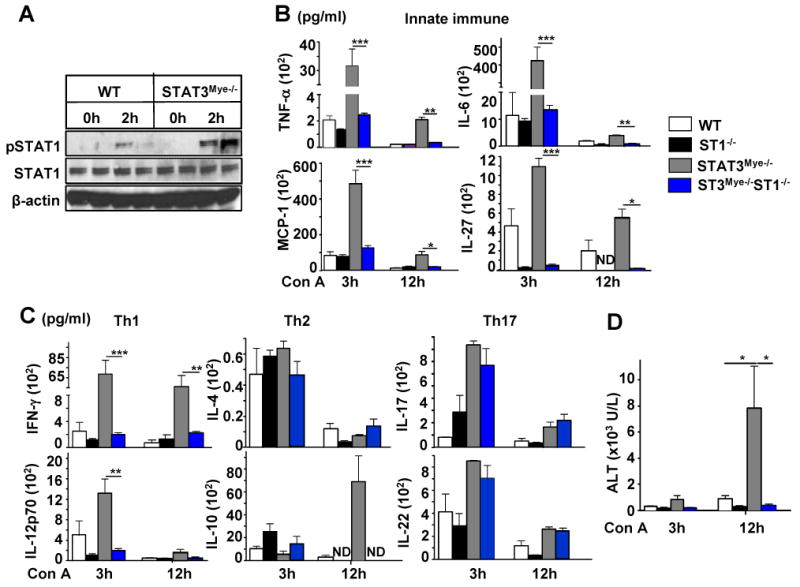

Deletion of STAT1 reduces innate and Th1 cytokines, but not Th2/Th17 cytokine production, and ameliorates liver injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice during T-cell hepatitis

Compared to wild-type mice, STAT3Mye-/- mice had enhanced pSTAT1 activation in the liver after Con A injection (Fig. 2C). Moreover, enhanced pSTAT1 activation was also observed in the splenocytes of STAT3Mye-/- mice compared with cells from wild-type mice (Fig. 7A). To define whether the enhanced STAT1 is responsible for the elevated Con A-induced liver injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice, we generated STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/- double knockout mice in which the STAT3 gene was disrupted in myeloid cells and the STAT1 gene was disrupted globally. Figs. 7B and 7C show serum cytokine levels from four lines of mice, including wild-type, STAT1-/-, STAT3Mye-/-, and double knockout mice. Serum levels of many inflammatory cytokines post Con A injection were comparable between STAT1-/- and wild-type mice, except for IL-27, IL-12, and IL-17. Both IL-12 and IL-27 were downregulated, while IL-17 was upregulated in STAT1-/- mice. Compared with wild-type mice, STAT3Mye-/- mice had markedly higher levels of many inflammatory cytokines, except IL-4, which was consistent with the findings in Fig. 2. The pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-27 and the chemokine MCP-1, as well as Th1 cytokines, were found at a significantly lower level in STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/- mice compared with STAT3Mye-/- mice (Figs. 7B-C). In contrast, serum levels of the Th2 cytokine, IL-4, and the Th17 cytokines, IL-17 and IL-22, were not repressed when STAT1 was additionally deleted in STAT3Mye-/- mice (STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/- mice) compared with STAT3Mye-/- mice (Fig. 7C). IL-10 production was also reduced in STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/- mice compared with STAT3Mye-/- mice. Finally, deletion of STAT1 completely prevented Con A-induced liver injury in STAT3Mye-/- mice (STAT3Mye-/- vs. STAT3Mye-/-STAT1-/-)(Fig. 7D). Compared with wild-type mice, STAT1-/- mice were resistant to Con A-induced liver injury, in agreement with earlier findings.15, 22

Fig. 7. Deletion of STAT1 in STAT3Mye-/- mice ameliorates liver injury and abolishes innate immune and Th1 but not Th2/Th17 cytokine production during Con A-induced hepatitis.

A, Activation of pSTAT1 in WT and STAT3Mye-/- splenocytes 2 hrs post Con A injection analysed by Western blotting. B-C, Serum levels of cytokines. D, Serum ALT levels. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.005 (n=3-6). ND for Not Detected.

Discussion

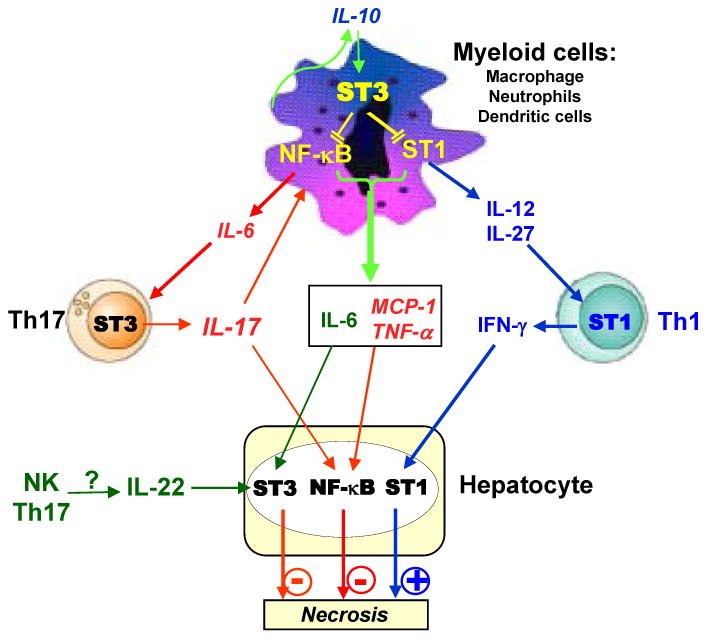

T cell activation in antigen-dependent (e.g. HCV and HBV) as well as in antigen-independent (e.g. drug intoxication, alcoholic liver diseases) mediated hepatitis has been shown to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of liver diseases.1-7 For example, in chronic HCV infection, while the virus itself has a non-cytolytic function, activation of CD8+ T cells kills viral infected hepatocytes via releasing perforin and granzyme, while activation of CD4+ T cells produces inflammatory cytokines and controls CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity, contributing to the progression of liver disease.1, 2 It has been well documented that T-cell hepatitis is controlled by the interplay between multiple signaling pathways induced by a wide variety of inflammatory, Th1 and Th2 cytokines.9 Data from the current study suggest that activation of STAT3 signaling pathway in myeloid cells and T cells play opposing roles in controlling Con A-induced hepatitis through differential regulation of these cytokines. The proposed interaction and effect of these cytokines are summarized in the model shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. A model depicting the hepatoprotection of myeloid cell STAT3 in T-cell hepatitis.

During T-cell hepatitis, myeloid cell STAT3 inhibits STAT1 signaling in these cells, followed by preventing IL-12/IL-27 production and subsequently inhibiting IL12/IL-27 stimulation of IFN-γ production by Th1 cells. Myeloid cell STAT3 inhibits STAT1 and NF-κB activation, followed by reducing production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) and subsequently inhibiting IL-6 stimulation of IL-17 production by Th17 cells. IFN-γ plays an essential role in T-cell hepatitis via induction of inflammation and hepatocyte death, while IL-17 only stimulates weakly liver inflammation but prevents hepatocyte death, thereby playing a double-edged sword role in T-cell hepatitis. Myeloid cell STAT3 also inhibits IL-22 production via unknown mechanisms.

Deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells enhanced preferentially the Th1 cytokine response during Con A-induced hepatitis (Fig. 2). Based on our findings, it is plausible to speculate that deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells results in enhanced STAT1 activation, which stimulates myeloid cells to produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-27, and IL-12. The latter 2 cytokines stimulate Th1 cells to produce IFN-γ, which subsequently contributes to liver injury. This cascade is supported by several lines of evidence. First, myeloid linage cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells, are the major producers of IL-12 and IL-27.36 Deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells promoted IL-12 and IL-27 production during Con A induced liver injury, while deletion of STAT1 diminished this effect (Fig. 7), suggesting that STAT3 inhibits while STAT1 promotes IL-12 and IL-27 production in myeloid cells. Second, both IL-12 and IL-27 have been shown to be the major cytokines to stimulate Th1 cells to produce IFN-γ.36 Deletion of IL-27 abrogated IFN-γ production during T-cell hepatitis,37 suggesting that IL-27 plays an important role in induction of IFN-γ in this model. Third, IL-27 can activate both STAT1 and STAT3 in T cells.38 Since deletion of STAT1 abolished (Fig. 7), but deletion of STAT3 in T cells had no effect on the production of IFN-γ (Fig. 4), it is likely that IL-27 induces IFN-γ production in T cells via activation of STAT1 during T-cell hepatitis. Lastly, the critical roles of this cascade have been clearly demonstrated in mice with ablation of the genes encoding STAT1 (Fig. 7),15, 22 IL-27,37 or IFN-γ.15 The latter 2 cytokines can activate STAT1 in hepatocytes, leading to hepatocellular injury.21, 39

Deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells also enhanced Th17 cytokine IL-17 in Con A-induced hepatitis. Several lines of evidence suggest that enhanced IL-17 production in STAT3Mye-/- mice after Con A injection is due to elevated IL-6 and T cell STAT3 activation. First, it has been well documented that IL-6 is required for Th17 cell differentiation and IL-17 production.31, 32 Production of IL-6 was higher in STAT3Mye-/- mice after injection of Con A (Fig. 2) and deletion of IL-6 markedly diminished IL-17 production (Fig. 3). Second, T cells from STAT3Mye-/- mice had enhanced activation of STAT3 (Fig. 3A), a signal that is essential for Th17 cell differentiation and IL-17 production.31, 32 Third, deletion of STAT3 in T cells markedly diminished IL-17 production during Con A-induced hepatitis. These findings suggest that myeloid and T cell STAT3 inhibits and promotes IL-17 production during T-cell hepatitis, respectively. Interestingly, IL-17 production showed an increasing, but not significant, trend in STAT1-/- mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 7C). This increase may be due to downregulation of IL-27 in STAT1-/- mice (Fig. 7B) as IL-27 is an important inhibitor for IL-17 production.40 In contrast, additional global deletion of STAT1 did not affect IL-17 production in STAT3Mye-/- mice (Fig. 7C). This may be because deletion of STAT1 not only abolished IL-27 production but also reduced IL-6 synthesis, an IL-17 stimulatory cytokine (Fig. 7B), leading to a minimal effect on IL-17 production.

Production of IL-22, another Th17 cytokine, was also higher in STAT3Mye-/- mice after Con A injection compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 2). This production was not affected after deletion of STAT3 in T cells (Fig. 4) or global deletion of STAT1 (Fig. 7), but was reduced in IL-6-/- mice (Fig. 3). This suggests that IL-6 may promote IL-22 production in a T cell STAT3-independent manner via activation of STAT3 in other cell types rather than T cells, as IL-22 can be produced by NK cells in addition to T cells.41 In contrast to STAT3, STAT1 had no effect on IL-22 production because global deletion of STAT1 did not modulate IL-22 production (Fig. 7).

We and others have previously demonstrated that the Th2 cytokine, IL-4, plays an essential role in inducing Con A-induced hepatitis via activation of STAT6.14 Here we demonstrated that deletion of STAT3 in myeloid cells or T cells, or global deletion of STAT1 had no effect on Th2 cytokine IL-4 production during T-cell hepatitis. This suggests that myeloid and T cell STAT3 and STAT1 do not affect IL-4 production during Con A-induced hepatitis, which is consistent with earlier findings that IL-4 is controlled by STAT6/GATA3.42

The extensive liver damage observed in STAT3Mye-/- mice was associated with an increase in innate and Th1 inflammatory cytokine production. Enhanced elevation of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-27 likely contributes to the exacerbated liver injury observed in STAT3Mye-/- mice because all of these cytokines have been shown to play an important role in Con A-induced hepatitis,15, 37 while enhanced elevation of hepatoprotective cytokines IL-6 15 and IL-22 16, 19 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 20 may play a compensatory role in preventing hepatitis in STAT3Mye-/- mice. Surprisingly, deletion of IL-17 did not reduce hepatitis in STAT3Mye-/- mice, suggesting enhanced IL-17 levels did not contribute to the enhanced hepatitis in these mice. This is probably because IFN-γ plays a dominant role while IL-17 has a less important function in inducing liver injury in this model (see discussion below), and the fold of IFN-γ elevation (35 fold) was much higher than IL-17 induction (9 fold) in STAT3Mye-/- mice after Con A injection compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 2F).

The critical roles of Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and Th2 cytokine IL-4 in T-cell hepatitis have been well documented;14, 15 while the findings regarding the role of IL-17 in this model have been controversial.16, 17 Zenewicz et al 16 reported that IL-17 did not play a role in Con A-induced hepatitis, while Nagata et al 17 showed that IL-17RA contributed to liver injury in this model. Our findings showed the difference in serum ALT between IL-17-/- and wild-type mice is small but reached statistical difference, which is consistent with Nagata et al.17 The reason for the discrepancy between our findings and Zenewicz et al 16 is not clear and could be attributed to the different environment of the animal facilities that may affect IL-17-/- mice. In contrast to the small difference in serum ALT levels between IL-17-/- and wild-type mice, the serum ALT levels were reduced by 90% in IFN-γ-/- mice compared to wild-type mice after Con A injection. These findings suggest that both IL-17 and IFN-γ participate to T-cell-mediated hepatitis, and that IL-17 plays a mild role as compared to the major contribution of IFN-γ. The essential role of IFN-γ in T-cell hepatitis is probably attributed to multiple detrimental functions of IFN-γ in the liver, including IFN-γ induction of hepatocyte apoptosis and cell cycle arrest,21 IFN-γ induction of expression of chemokines and their receptors on liver cells,34 and IFN-γ activation of Kupffer cells/macrophages.43 Although IL-17 also targets multiple cell types in the liver to induce expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines44 (Fig. 5D), IL-17 protects against rather than potentiates IFN-γ-induced hepatocyte apoptosis (Fig. 5F). In addition, intraperitoneal injection of IL-17 caused recruitment of neutrophils into the peritoneum 45 and intratracheal instillation of IL-17 markedly induced recruitment of neutrophils into the lung.46 However, neither intraperitoneal nor intrahepatic injection of IL-17 caused liver injury and neutrophil recruitment into the liver (Lafdil and Gao, unpublished observation). Taken together, these findings suggest that IL-17 appears to play a less important role in T-cell hepatitis than IFN-γ. Although serum levels IFN-γ were comparable between STAT3T cell-/- and wild-type mice after Con A injection (Fig. 4B), liver injury (serum ALT) was reduced in STAT3T cell-/- than wild-type mice. Such reduced liver injury in STAT3 T cell-/- mice may be attributed to a decrease in IL-17 in these mice as IL-17 has been shown to contribute to Con A-induced hepatitis (Fig. 5).

Taken together, our findings suggest that myeloid STAT3 inhibits T-cell hepatitis via downregulation of a variety of cytokines. In macrophage, STAT3 inhibits STAT1 signaling pathway, followed by attenuating IL-12, IL-27, and IFN-γ production. STAT3 may also inhibit NF-κB signaling pathway,47 leading to a decrease in IL-6, MCP-1, and TNF-α production. Finally, many of these cytokines can target hepatocytes, leading to enhanced activation of several signaling pathways including STAT1, STAT3, and NF-κB (Fig. 2C) that either promote or prevent hepatocellular injury during T-cell hepatitis. The outcome and progression of liver injury are determined by the balance between these signaling pathways. Activation of STAT3 in myeloid cells or blocking IFN-γ could be novel therapeutic strategies to treat T-cell hepatitis in patients, while blockage of IL-17 may not be effective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural program of NIAAA, NIH.

Abbreviations

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3

- STAT3T-cell-/- mice

T-cell-specific STAT3 knock out mice

- STAT3Mye-/- mice

myeloid cell-specific STAT3 knock out mice

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

Footnotes

FL, HW, OP, WZ, YM, SY, XF: Perform the experiments; FL, BG: study concept and design and drafting of the manuscript; MEG, ZXL, BG: critical revision of the manuscript and study supervision. All authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chang KM. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:89–105. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehermann B. Intrahepatic T cells in hepatitis B: viral control versus liver cell injury. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1263–1268. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamantis I, Boumpas DT. Autoimmune hepatitis: evolving concepts. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He XS, Ansari AA, Ridgway WM, Coppel RL, Gershwin ME. New insights to the immunopathology and autoimmune responses in primary biliary cirrhosis. Cell Immunol. 2006;239:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiele GM, Freeman TL, Klassen LW. Immunologic mechanisms of alcoholic liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:273–287. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell CC, Tschoep J, Lentsch AB. Lymphocyte function during hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:457–464. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen HR. Transplantation immunology: what the clinician needs to know for immunotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1789–1801. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiegs G, Hentschel J, Wendel A. A T cell-dependent experimental liver injury in mice inducible by concanavalin A. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:196–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI115836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiegs G. Cellular and cytokine-mediated mechanisms of inflammation and its modulation in immune-mediated liver injury. Z Gastroenterol. 2007;45:63–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-927397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Van Kaer L, Matsuda H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Critical contribution of liver natural killer T cells to a murine model of hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5498–5503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040566697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakashima H, Kinoshita M, Nakashima M, Habu Y, Shono S, Uchida T, et al. Superoxide produced by Kupffer cells is an essential effector in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2008;48:1979–1988. doi: 10.1002/hep.22561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonder CS, Ajuebor MN, Zbytnuik LD, Kubes P, Swain MG. Essential role for neutrophil recruitment to the liver in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:45–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis H, Le Moine A, Flamand V, Nagy N, Quertinmont E, Paulart F, et al. Critical role of interleukin 5 and eosinophils in concanavalin A- induced hepatitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2001–2010. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaruga B, Hong F, Sun R, Radaeva S, Gao B. Crucial Role of IL-4/STAT6 in T Cell-Mediated Hepatitis: Up-Regulating Eotaxins and IL-5 and Recruiting Leukocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171:3233–3244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong F, Jaruga B, Kim WH, Radaeva S, El-Assal ON, Tian Z, et al. Opposing roles of STAT1 and STAT3 in T cell-mediated hepatitis: regulation by SOCS. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1503–1513. doi: 10.1172/JCI15841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Karow M, Flavell RA. Interleukin-22 but not interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute liver inflammation. Immunity. 2007;27:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata T, McKinley L, Peschon JJ, Alcorn JF, Aujla SJ, Kolls JK. Requirement of IL-17RA in Con A induced hepatitis and negative regulation of IL-17 production in mouse T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7473–7479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gantner F, Leist M, Lohse AW, Germann PG, Tiegs G. Concanavalin A-induced T-cell-mediated hepatic injury in mice: the role of tumor necrosis factor. Hepatology. 1995;21:190–198. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radaeva S, Sun R, Pan HN, Hong F, Gao B. Interleukin 22 (IL-22) plays a protective role in T cell-mediated murine hepatitis: IL-22 is a survival factor for hepatocytes via STAT3 activation. Hepatology. 2004;39:1332–1342. doi: 10.1002/hep.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erhardt A, Biburger M, Papadopoulos T, Tiegs G. IL-10, regulatory T cells, and Kupffer cells mediate tolerance in concanavalin A-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2007;45:475–485. doi: 10.1002/hep.21498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun R, Park O, Horiguchi N, Kulkarni S, Jeong WI, Sun HY, et al. STAT1 contributes to dsRNA inhibition of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:955–966. doi: 10.1002/hep.21344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siebler J, Wirtz S, Klein S, Protschka M, Blessing M, Galle PR, et al. A key pathogenic role for the STAT1/T-bet signaling pathway in T-cell-mediated liver inflammation. Hepatology. 2003;38:1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein C, Wustefeld T, Assmus U, Roskams T, Rose-John S, Muller M, et al. The IL-6-gp130-STAT3 pathway in hepatocytes triggers liver protection in T cell-mediated liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:860–869. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luedde T, Assmus U, Wustefeld T, Meyer zu Vilsendorf A, Roskams T, Schmidt-Supprian M, et al. Deletion of IKK2 in hepatocytes does not sensitize these cells to TNF-induced apoptosis but protects from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:849–859. doi: 10.1172/JCI23493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beraza N, Ludde T, Assmus U, Roskams T, Vander Borght S, Trautwein C. Hepatocyte-specific IKK gamma/NEMO expression determines the degree of liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2504–2517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda S, Chang L, Li ZW, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKbeta is required for prevention of apoptosis mediated by cell-bound but not by circulating TNFalpha. Immunity. 2003;19:725–737. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakamori R, Takehara T, Ohnishi C, Tatsumi T, Ohkawa K, Takeda K, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling within hepatocytes attenuates systemic inflammatory response and lethality in septic mice. Hepatology. 2007;46:1564–1573. doi: 10.1002/hep.21837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haga S, Terui K, Zhang HQ, Enosawa S, Ogawa W, Inoue H, et al. Stat3 protects against Fas-induced liver injury by redox-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:989–998. doi: 10.1172/JCI17970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das M, Sabio G, Jiang F, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Induction of hepatitis by JNK-mediated expression of TNF-alpha. Cell. 2009;136:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsukawa A, Kudo S, Maeda T, Numata K, Watanabe H, Takeda K, et al. Stat3 in resident macrophages as a repressor protein of inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2005;175:3354–3359. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. Signal transduction pathways and transcriptional regulation in the control of Th17 differentiation. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong C. Regulation and pro-inflammatory function of interleukin-17 family cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–467. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaruga B, Hong F, Kim WH, Gao B. IFN-{gamma}/STAT1 acts as a proinflammatory signal in T cell-mediated hepatitis via induction of multiple chemokines and adhesion molecules: a critical role of IRF-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1044–G1052. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geisler F, Algul H, Paxian S, Schmid RM. Genetic inactivation of RelA/p65 sensitizes adult mouse hepatocytes to TNF-induced apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2489–2503. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siebler J, Wirtz S, Frenzel C, Schuchmann M, Lohse AW, Galle PR, et al. Cutting edge: a key pathogenic role of IL-27 in T cell- mediated hepatitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:30–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucas S, Ghilardi N, Li J, de Sauvage FJ. IL-27 regulates IL-12 responsiveness of naive CD4+ T cells through Stat1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15047–15052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536517100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bender HWM, Nordhoff C, Schoenherr C, Haan C, Ludwig S, Weiskirchen R, Kato N, Heinrich PC, Haan S. Interleukin-27 displays interferon-gamma-like functions in human hepatoma cells and hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hep.22988. on line. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida H, Miyazaki Y. Interleukin 27 signaling pathways in regulation of immune and autoimmune responses. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2379–2383. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolk K, Sabat R. Interleukin-22: A novel T- and NK-cell derived cytokine that regulates the biology of tissue cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ansel KM, Djuretic I, Tanasa B, Rao A. Regulation of Th2 differentiation and Il4 locus accessibility. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:607–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zocco MA, Carloni E, Pescatori M, Saulnier N, Lupascu A, Nista EC, et al. Characterization of gene expression profile in rat Kupffer cells stimulated with IFN-alpha or IFN-gamma. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:563–577. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemmers A, Moreno C, Gustot T, Marechal R, Degre D, Demetter P, et al. The interleukin-17 pathway is involved in human alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:646–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witowski J, Pawlaczyk K, Breborowicz A, Scheuren A, Kuzlan-Pawlaczyk M, Wisniewska J, et al. IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO alpha chemokine from mesothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5814–5821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lotvall J, Sjostrand M, Gruenert DC, et al. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol. 1999;162:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Z, Kone BC. The STAT3 DNA-binding domain mediates interaction with NF-kappaB p65 and iuducible nitric oxide synthase transrepression in mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:585–591. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000114556.19556.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.