Abstract

Background:

Cystic fibrosis (CF) lung disease is characterized by structural changes in the airways and parenchyma. No sputum biomarker exists to measure the degree of active structural destruction during pulmonary exacerbation in patients with CF. The noninvasive measurement of desmosine, a breakdown product of elastin, may reflect ongoing lung injury and serve as a biomarker of short-term damage. Our objectives were to measure desmosine in the sputum of patients with CF hospitalized for treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation and to explore the correlation between desmosine levels and other markers of clinical improvement, including lung function and inflammatory mediators, following hospitalization.

Methods:

Sputum and blood samples collected and lung function measurements were made at multiple time points during hospitalization. We used a repeated measures model, adjusted for age and time between measurements, to compare log-transformed sputum desmosine levels across multiple time points and to correlate those levels with related variables.

Results:

Desmosine levels were measured by radioimmunoassay in 71 expectorated sputum samples from 19 patients with CF hospitalized for 26 pulmonary exacerbations (range of results, 0 to 200 pmol/L desmosine/mL). Sputum desmosine levels decreased significantly during the first week of hospitalization (p = 0.04). Desmosine levels were positively associated with plasma C-reactive protein (ρ = 0.59; p = 0.03), sputum interleukin-8 (ρ = 0.86; p < 0.01), and sputum neutrophil elastase (ρ = 0.78; p < 0.01).

Conclusions:

Sputum desmosine, a novel measure of acute structural lung injury, may serve as a marker of structural lung damage occurring during exacerbations of lung disease in CF.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) produces progressive lung disease and related morbidity and mortality in >90% of patients.1 Abnormalities in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator protein result in abnormal airway surface liquid that impairs mucociliary clearance. Mucus becomes a site for bacterial colonization and a resulting neutrophilic inflammatory response. These neutrophils release oxidants and proteases that degrade tissue and eventually cause permanent fibrotic change of the airways and lung parenchyma of patients with CF.2

The search for sputum biomarkers to monitor airway inflammation and structural change in CF is ongoing.3 Sputum provides a noninvasive source of potential biomarkers, given the direct involvement of airway inflammation in the pathophysiology of CF lung disease.4 Lung disease in CF patients, including structural change and bronchiectasis, begins early and often in the absence of pulmonary symptoms.5–7 Lung function declines at a rate of 1% to 2% per year, with the conditions of some patients progressing more rapidly.8 This decline is related to chronic bacterial colonization, pulmonary exacerbations, persistent airway inflammation, and remodeling of the respiratory system. The early identification and aggressive treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation may prevent ongoing lung damage and may have the potential to preserve lung function and improve quality of life. A biomarker of structural injury during an exacerbation may provide the opportunity to both intervene earlier and more accurately monitor the CF lung during times of illness.

Aggressive treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation decreases sputum bacterial burden, improves pulmonary function, and decreases airway markers of inflammation and infection.9–11 However, no biomarker has been identified to reflect the degree of active lung destruction occurring during a pulmonary exacerbation in CF. Thus, the relationship between an exacerbation and lung injury is currently not known.

Desmosine, a breakdown product of the airway and alveolar matrix component elastin may reflect ongoing lung injury and may serve as a biomarker of active damage during pulmonary exacerbation. In multiple cross-sectional analyses of small numbers of adult patients with COPD, sputum levels of desmosine were determined to be elevated compared with nonsmoking control subjects.12–14 Desmosine is also excreted in the urine, and levels can be elevated in patients with CF.15,16 No investigator, however, has examined sputum desmosine concentrations serially in a cohort of well-characterized patients with CF during pulmonary exacerbation. We hypothesized that pulmonary exacerbations in patients with CF cause active airway and parenchymal injury, and result in measurable levels of desmosine in sputum. Our aim was to measure sputum desmosine levels during inpatient treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation in patients with CF and to explore the use of desmosine as an objective biomarker through correlation with previously reported markers of clinical improvement.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Nineteen patients who had been given a confirmed diagnosis of CF were identified on admission to the Children's Hospital, Denver, for treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation and were recruited into our study.17 A pulmonary exacerbation was defined as an increase in pulmonary symptoms (ie, cough or sputum production), a >10% decrease in FEV1 compared with baseline and/or attending physician clinical judgment. Patients were required to have two or more IV antibiotics administered for treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation and be able to spontaneously expectorate sputum to enroll in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and informed consent and/or assent were obtained from each of the subjects and/or their parents or guardians.

Study Design

This was a single-center, prospective cohort study of patients with CF who were hospitalized for a pulmonary exacerbation. All patients received standard-of-care therapies including airway clearance, nutritional support, and IV antibiotics. Standard doses of IV antibiotics were used, and blood levels were monitored where appropriate. Each subject provided an expectorated sputum sample and a blood sample, and underwent pulmonary function tests within 72 h of the initiation of therapy with IV antibiotics on day 3 to 8 of therapy and on day 8 to 12 of therapy. Sputum was processed as previously described and frozen immediately after collection at −80°C prior to shipment for desmosine analysis.18

Laboratory Assays

Sputum Sample Analysis:

Desmosine concentration was measured in sputum samples treated with protease inhibitors using a radioimmunoassay (RIA) [Elastin Products, Inc; Owensville, MO].19–22 Results are expressed as picomoles of desmosine per milliliter of sputum. The lower limit of detection was 2 pmol/L. Sputum interleukin (IL)-8 and free neutrophil elastase (NE) were measured on each sputum specimen in duplicate. IL-8 was measured by using assays (Luminex Multiplex Beads; R&D Systems; Abingham, Oxon, UK), and free NE activity was quantified by spectrophotometric assay (Sigma Diagnostics; St. Louis, MO). The lower limits of detection for these assays were 0.5 μg/mL and <2.0 pg/mL, respectively. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures were performed during each hospital admission.

Blood Sample Analysis:

C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-8 were measured on each sample. CRP was measured by nephelometry (Cardiophase hsCRP, BN11 instrument; Siemens; DeerField, IL) and IL-8 was measured by assays (Luminex Multiplex Beads; R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN). The lower limits of detection for these assays were 0.01 mg/L and <2.0 pg/mL, respectively.

Pulmonary Function Testing:

Testing was performed according to American Thoracic Society guidelines.23 The functional indexes measured included FEV1 and FVC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated by using medians, ranges, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) where specified, for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Log transformation (base 10) was used to normalize the distribution of all variables. To estimate the means in the outcome variables for multiple time points, a repeated measures model was fit with age and time between measurements included as covariates. This model included a compound symmetric covariance structure for the repeated measures and contrasts testing the least square means between two time points. To assess the correlation between sputum desmosine levels and other outcome variables, a bivariate version of the repeated measures model was fit. This modeling approach is achieved by simultaneously fitting two univariate repeated measures models, one for each outcome, and specifying a joint multivariate distribution on the random effects and calculating their correlation.24 Differences between a patient's first and last log-transformed measurements were used to investigate the correlation of changes in the outcome variables. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which a nested random effect was included in the mixed effects models to account for the repeated admissions. All models were fit by using a statistical software package (SAS PROC MIXED, version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Demographics

Demographic data from 19 patients, involving 26 hospitalizations for pulmonary exacerbation, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Hospital admissions | 26 |

| Subjects | 19 |

| Length of stay, d | 13 (9–21) |

| Age, yr | 19.8 (6.7–36.8) |

| Female patients | 13 (50) |

| F508 mutation | 23 (88.5) |

| White patients | 26 (100) |

| Admission FEV1, % predicted | 42.0 (26–110.0) |

| Duration of antibiotic treatment, d | 12.5 (8–21) |

| Antibiotics used | |

| Azithromycin | 23 (88) |

| Aminoglycoside | 22 (85) |

| Cephalosporin | 14 (54) |

| Meropenem | 12 (46) |

| Fluoroquinolone | 11 (42) |

| Antifungal agent | 8 (31) |

| Other | 14 (54) |

| Time between IV antibiotics and first sputumsample collection, d | 1 (−1–3) |

| Culture positive | |

| > 1 pathogen | 23 (88) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 20 (77) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 7 (27) |

| MRSA | 7 (27) |

| Atypical mycobacteria | 4 (15) |

| Fungus | 9 (35) |

| Other | 3 (12) |

Values are presented as No. (%) or median (range).

Sputum Desmosine Levels

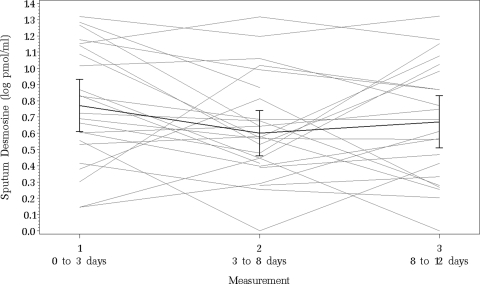

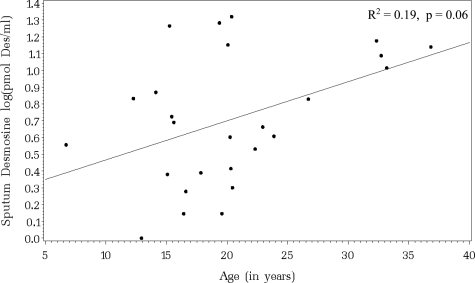

We collected 71 expectorated sputum samples during 26 hospitalizations for pulmonary exacerbation. The untransformed sputum desmosine measurements ranged from 0 to 200 pmol desmosine/mL. The initial median sputum desmosine level was 43.0 pmol desmosine/mL (IQR range, 24.0 to 128.0 pmol desmosine/mL; n = 23). The interim median sputum desmosine level was 27.3 pmol desmosine/mL (IQR range, 15.0 to 5.0 pmol desmosine/mL; n = 26), and the final median sputum desmosine level was 34.8 pmol desmosine/mL (IQR range, 11.5 to 86.0 pmol desmosine/mL; n = 22). Figure 1 illustrates the log-transformed sputum desmosine measurements for each patient at each time point. The association between the initial log-transformed sputum desmosine value and age is shown in Figure 2. The linear relationship shows a trend toward significance with older patients having higher initial sputum desmosine values (R2 = 0.19; p = 0.06).

Figure 1.

Log-transformed sputum desmosine concentrations for each patient hospitalized for pulmonary exacerbation at each of three collection points. The bold line represents the average concentration with ± 2 SE bars for each collection point. Sputum desmosine concentration decreased significantly between the first and second time point (p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Linear association between initial sputum desmosine values regressed on age (R2 = 0.37; p = 0.06).

Change in Sputum Desmosine, Lung Function, Blood, and Sputum Inflammatory Markers During Hospitalization

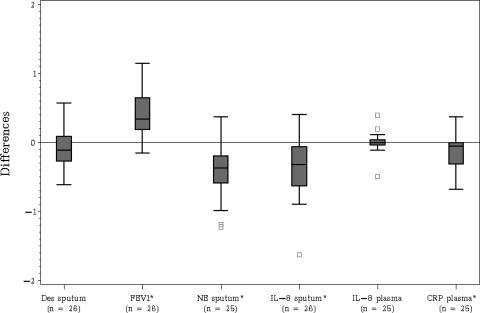

Table 2 summarizes the differences among each of three time points in the primary outcome variables during inpatient treatment for exacerbation. Our patient population improved clinically as demonstrated by a significant increase in absolute FEV1 and a significant decrease in sputum NE, sputum IL-8, and plasma CRP concentrations. Sputum desmosine values decreased significantly between the first and second measurements (p = 0.04), as did the values of sputum NE (p = 0.05), sputum IL-8 (p<0.01), and plasma CRP (p<0.01). Sputum desmosine levels trended toward an increase between the second and third measurements, as did sputum IL-8, plasma IL-8, and plasma CRP. Overall, sputum desmosine showed a trend toward decreasing, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.30). A sensitivity analysis performed to evaluate the effect of repeat hospital admissions on the change in sputum desmosine did not change the estimates; however, the related statistical significance was affected due to a loss of power.

Table 2.

Summary of Differences in Primary Outcome Variables at Each of Three Time Points During Inpatient Treatment for Pulmonary Exacerbation

| Variables | Time 2 vs 1 | Time 3 vs 2 | Time 3 vs 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sputum desmosine, log pmol/mL | −0.14 ± 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.07 | 0.33 | −0.07 ± 0.07 | 0.30 |

| FEV1 absolute, L | 0.32 ± 0.06 | < 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | < 0.01 |

| Sputum NE, log μg/mL | −0.18 ± 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.19 ± 0.09 | 0.05 | −0.36 ± 0.09 | < 0.01 |

| Sputum IL-8, log pg/mL | −0.31 ± 0.09 | < 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.09 | 0.98 | −0.31 ± 0.10 | < 0.01 |

| Plasma IL-8, log pg/mL | −0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.83 |

| Plasma CRP, log mg/L | −0.17 ± 0.04 | < 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.84 | −0.16 ± 0.05 | < 0.01 |

Values are given as the estimate ± SE and p values for differences between least square means. Results of a repeated measures analysis of covariance model, adjusted for differences in time between measurements and age are given.

Correlations of Sputum Desmosine With Lung Function, Blood, and Sputum Inflammatory Markers

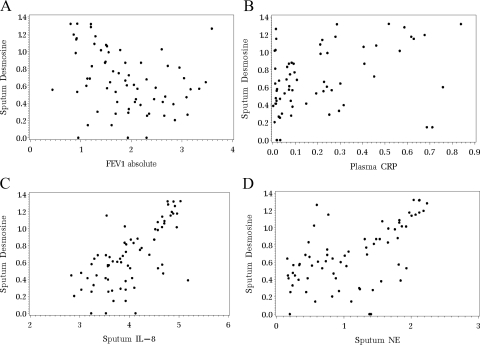

Figure 3 illustrates the correlation (ρ) between log-transformed sputum desmosine levels and the log-transformed primary outcome variables. There was a nonsignificant, negative association observed between sputum desmosine and absolute FEV1 (ρ = −0.31; p = 0.20). Positive associations were observed between levels of sputum desmosine and plasma CRP (ρ = 0.59; p = 0.03), sputum IL-8 (ρ = 0.86; p<0.01), and sputum NE (ρ = 0.78; p<0.01).

Figure 3.

Results of a bivariate version of the repeated measures model to determine correlations between sputum desmosine values and primary outcome variables. A: sputum desmosine is not significantly correlated with absolute FEV1, although a negative association was observed (ρ = −0.31; p = 0.20). B: sputum desmosine is positively associated with plasma CRP (ρ = 0.59; p = 0.03). C: sputum desmosine is positively associated with sputum IL-8 (ρ = 0.86; p<0.01). D: sputum desmosine is positively associated with sputum NE (ρ = 0.78; p<0.01).

Correlations of Changes in Sputum Desmosine With Changes in Lung Function, Blood, and Sputum Inflammatory Markers

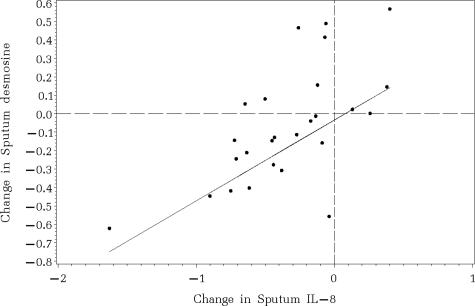

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of the differences in log-transformed values between the first and last measurements for each outcome variable. After inpatient treatment for pulmonary exacerbation, absolute FEV1 increased significantly (p<0.01), and sputum NE, sputum IL-8, and plasma CRP all decreased significantly (p<0.01). Only the difference in sputum IL-8 levels yielded a significant association with the difference in sputum desmosine levels (Pearson correlation = 0.64; p = 0.02) [Fig 5].

Figure 4.

Boxplots displaying the distribution of the unadjusted differences between the first and last measurement separately for each outcome variable. * = mean difference significantly different from 0 by using p<0.05.

Figure 5.

Association between the differences of sputum desmosine and sputum IL-8. Values below zero indicate a decrease in the measurements over time. Sputum desmosine and sputum IL-8 decreased significantly together during hospitalization (Pearson correlation = 0.64; p = 0.02).

Discussion

We sought to explore sputum desmosine as a biomarker of acute structural lung injury during hospitalization for a CF pulmonary exacerbation. We chose an acute pulmonary exacerbation because subjects treated with IV antibiotics and enhanced mucus clearance generally display clinical improvement within 2 weeks. Our study demonstrates that desmosine can be detected by RIA in the expectorated sputum of patients with CF during exacerbation. This finding is important, given that sputum can be obtained noninvasively and obviates the need for bronchoscopy. Few studies have previously demonstrated the measurement of sputum desmosine, and none have examined it serially and longitudinally, or explored its potential applications. Ma and colleagues12,13 measured sputum desmosine by using mass spectrometry in a small number of patients with COPD and adult control subjects without lung disease. Boschetto et al14 measured sputum desmosine levels in patients with COPD and healthy nonsmokers by using capillary electrophoresis. Our sputum desmosine concentrations are higher than those reported by these investigators, likely secondary to a difference in technique or to a difference in disease state. Although our reported levels are dissimilar, the correlation of sputum desmosine levels with well-studied inflammatory markers lends validity to our conclusion that desmosine may be a marker of structural injury.

To date, there have been no published reports of desmosine concentration in the sputum of CF patients. This may be secondary to specimen availability, given that even patients with CF who are experiencing an exacerbation have difficulty expectorating.18,25 However, it is interesting that our patients who could expectorate tended to be older and had relatively low lung function on hospital admission. We found that sputum desmosine levels exhibited a positive trend with age, suggesting that the older population tended to be sicker with biochemical evidence of more structural airway damage on admission than their younger counterparts.

We arbitrarily chose to collect specimens at up to three time points. Sputum desmosine levels tended to mirror those of other mediators. From measurement 1 to 2, sputum desmosine levels decreased significantly, as did levels of sputum NE, sputum IL-8, and plasma CRP. From measurement 2 to 3, sputum desmosine levels tended to increase slightly, as did levels of sputum IL-8 and plasma CRP. Finally, between measurements 1 and 3 sputum desmosine levels tended to decrease, as did levels of sputum NE, sputum IL-8, and plasma CRP. The overall decrease in sputum desmosine was nonsignificant, but this may be due to a small sample size. It also may be that sputum desmosine may be most sensitive during the first 3 to 8 days of therapy, and its decrease may signify a rapid decrease in inflammation in the CF airway. This observation remains to be fully elucidated.

Elastin is a major component of the airway wall and lung interstitium.26,27 Desmosine cross-links elastin to provide the lung with its tensile strength and stability.28 It is known that CF lung disease involves proteolytic destruction of connective tissue which results in structural changes to airways and alveolar parenchyma.16 Sputum NE activity, which destroys elastin in the airway wall, is known to be higher in patients with CF compared with that in normal control subjects.18 Hilliard et al29 showed that total elastin levels in BAL fluid are significantly higher in patients with CF compared with those in children with chronic respiratory symptoms and normal control subjects. These levels correlated with NE activity, matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels, and neutrophil concentration.29 Our findings of increased levels of desmosine in expectorated sputum, coupled with the absence of desmosine in normal control subjects in previous studies, serves to further indicate that elastin breakdown is occurring and desmosine may serve as a marker of this injury.

Urinary desmosine concentration is known to be increased in patients with destructive lung diseases such as COPD and CF compared with control subjects.12,13,15,16,30,31 Using a similar RIA, Starcher et al31 found a wide range of urinary desmosine levels in patients with CF (75 to 325 pmol desmosine/mg creatinine) with a significant amount of day-to-day variation. Downey et al32 found that higher levels of urinary desmosine were associated with a poorer outcome at 1 year in a CF population. Desmosine is an intriguing potential biomarker of lung damage, but, given the significant variability in its concentration in urine, sputum desmosine may be more representative of true lung structural damage given its proximity to the site of injury.

Our study is not without limitation. One limitation is the lack of control sputum specimens for comparison. Although we do not report control specimens, previous publications have documented nondetectable levels of desmosine in the sputum of adults without lung disease.12,13 During our analysis, we chose not to normalize sputum desmosine levels. Unlike BAL fluid, which requires normal saline solution for collection, expectorated sputum samples do not, negating the need to account for dilution. Sagel et al18 measured levels of inflammatory mediators in CF sputum both with and without a normalizing factor and found no significant difference.17 A final issue involves the level of disease severity within our study population. With a low median FEV1 percent predicted value, our patients with CF were sicker, resulting in a selection bias. However, examining desmosine levels in sick patients with CF provides the best opportunity to investigate its behavior to see if it warrants further study.

We selected an RIA to measure desmosine because this was a technique used in previous studies. While the RIA provides reproducible results and the specificity of the antibody for desmosine has been documented in both urine and lung homogenates,19,33 recent methodological advances34 in liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry may allow for more sensitive and specific measurements of desmosine for future studies.

The first step in evaluating a sputum biomarker as a potential outcome measure for a CF clinical study is to establish it has clinical and biological relevance.35 This study aimed to explore the use of sputum desmosine as a noninvasive biomarker of structural lung injury in a CF population who experienced pulmonary exacerbation by using a novel technique. Our results confirm that sputum desmosine may represent a valuable marker of tissue injury that might capture valuable information that lung function alone does not. It may also serve as an outcome measure in future studies or as one component of a future panel of biomarkers used to evaluate structural lung damage in a host of lung diseases. This study provides support for the continued investigation of sputum desmosine as a biomarker of acute structural lung injury in CF patients.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr. Laguna was involved in the conception and design of this protocol, as well as the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. She drafted the submitted article and provided final approval of the version to be published. She was the primary investigator for this study. Dr. Wagner was involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. She revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. Ms. Luckey made substantial contributions to the design of this study as the Bioinformatics Database Developer in the Pediatric Pulmonary Department at the University of Colorado. She revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. Ms. Mann made substantial contributions to the design of this study as the Research Coordinator in the Pediatric Pulmonary Department at the University of Colorado. She revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Sagel was involved in the conception and design of this protocol. He revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Regelmann made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of the data. He revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published. Dr. Accurso was involved in the conception and design of this protocol. He revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the version to be published.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: Dr. Laguna has received grant support from the American Thoracic Society and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. She has provided an educational symposium sponsored by Hill-Rom. Dr. Sagel has received grant support from the University of Colorado Clinical Translational Science Award, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. He has also received industry funding from Yasoo Health, Incorporated, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Incorporated. Dr. Regelmann has received grant support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutic Development Network. He serves as an advisor for the National Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis sponsored by Genentech. Dr. Accurso has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. He has served as a consultant to Inspire Pharmaceuticals, Inc, in the last 3 years. He has participated in industry studies through the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutic Development Network (Gilead Sciences, Inc; Targeted Genetics, Inc; PTC Therapeutics, Inc; Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Altus Biologics, Inc; Digestive Care, Inc; KalobBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc). Dr. Wagner, Ms. Luckey, and Ms. Mann have reported to the ACCP that no significant conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Abbreviations:

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- IL

interleukin

- IQR

interquartile range

- NE

neutrophil elastase

- RIA

radioimmunoassay

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This study was funded by grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF LAGUNA06A0) and the National Institutes of Health [grants 1U01HL081335-01 and M01RR00069].

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml).

References

- 1.Welsh MJ, Ramsey BW, Accurso FJ, et al. Metabolic and molecular basis of inherited disease. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2001. pp. 521–588. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsui H, Grubb BR, Tarran R, et al. Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell. 1998;95:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagel SD, Chmiel JF, Konstan MW. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:406–417. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-044BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chmiel JF, Berger M, Konstan MW. The role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of CF lung disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002;23:5–27. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:23:1:005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn TZ, Wagener JS, Bost T, et al. Early pulmonary inflammation in infants with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;151:1075–1082. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiddens HAWM, de Jong PA. Imaging and clinical trials in cystic fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:343–346. doi: 10.1513/pats.200611-174HT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranganathan SC, Dezateux C, Bush A, et al. Airway function in infants newly diagnosed with cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2001;358:1964–1965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Que C, Cullinan P, Geddes D. Improving rate of decline of FEV1 in young adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2006;61:155–157. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.043372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AL, Redding G, Doershuk C, et al. Sputum changes associated with therapy for endobronchial exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1988;112:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ordonez CL, Henig NR, Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Inflammation and microbiologic markers in induced sputum after intravenous antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1471–1475. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-731OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downey DG, Brockbank S, Martin SL, et al. The effect of treatment of cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations on airways and systemic inflammation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:729–735. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma S, Lieberman S, Turino GM, et al. The detection and quantitation of free desmosine and isodesmosine in human urine and their peptide-bound forms in sputum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12941–12943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235344100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma S, Lin YY, Turino GM. Measurements of desmosine and isodesmosine by mass spectrometry in COPD. Chest. 2007;131:1363–1371. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boschetto P, Quintavalle S, Zeni E, et al. Association between markers of emphysema and more severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2006;61:1037–1042. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.058321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone PJ, Konstan MW, Berger M, et al. Elastin and collagen degradation products in urine of patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:157–162. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.1.7599816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruce MC, Poncz L, Klinger JD, et al. Biochemical and pathologic evidence for proteolytic destruction of lung connective tissue in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:529–535. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenstein BJ, Cutting GR. The diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: a consensus statement. J Pediatr. 1998;132:589–595. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sagel SD, Kapsner R, Osberg I, et al. Airway inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy children assessed by sputum induction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1425–1431. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.8.2104075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King GS, Mohan VS, Starcher BC. Radioimmunoassay for desmosine. Connect Tissue Res. 1980;7:263–267. doi: 10.3109/03008208009152362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starcher B, Green M, Scott M. Measurement of urinary desmosine as an indicator of acute pulmonary disease. Respiration. 1995;62:252–257. doi: 10.1159/000196458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starcher BC, Conrad M. A role for neutrophil elastase in the progression of solar elastosis. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;31:133–140. doi: 10.3109/03008209509028401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starcher BC. A ninhydrin-based assay to quantitate the total protein content of tissue samples. Anal Biochem. 2001;292:125–129. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thiebaut R, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Chene G, et al. Bivariate linear mixed models using SAS proc MIXED. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2002;69:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griesenbach U, Jeswiet SB, Larsen MD, et al. UK CF Gene Therapy Consortium Tracking Study: change in sputum properties in response to IV antibiotic. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl. 2007;42:229. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starcher B, Peterson B. The kinetics of elastolysis: elastin catabolism during experimentally induced fibrosis. Exp Lung Res. 1999;25:407–424. doi: 10.1080/019021499270169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer RR, Crapo JD. Spatial distribution of collagen and elastin fibers in the lungs. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:756–765. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starcher BC. Lung elastin and matrix. Chest. 2000;117:229–234. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.229s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilliard TN, Regamey N, Shute JK, et al. Airway remodeling in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2007;62:1074–1080. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.074641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bode DC, Pagani ED, Cumiskey WR, et al. Comparison of urinary desmosine excretion in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cystic fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2000;13:175–180. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2000.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starcher B, Green M, Scott M. Measurement of urinary desmosine as an indicator of acute pulmonary disease. Respiration. 1995;62:252–257. doi: 10.1159/000196458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downey DG, Martin SL, Dempster M, et al. The relationship of clinical and inflammatory markers to outcome in stable patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:216–220. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuhn C, III, Engleman W, Chraplyvy M, et al. Degradation of elastin in experimental elastase-induced emphysema measured by a radioimmunoassay for desmosine. Exp Lung Res. 1983;5:115–123. doi: 10.3109/01902148309061508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luisetti M, Ma S, Iadarola P, et al. Desmosine as a biomarker of elastin degradation in COPD: current status and future directions. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1146–1157. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer-Hamblett N, Ramsey BW, Kronmal RA. Advancing outcome measures for the new era of drug development in cystic fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:370–377. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-040BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]