Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

In contrast to microalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients, the factors correlated with urinary albumin excretion are less well known in normoalbuminuric patients. This may be important because even within the normoalbuminuric range, higher rates of albuminuria are known to be associated with higher renal and cardiovascular risk.

Methods

At the time of screening for the Randomised Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) Study, the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) was 0.44 mg/mmol in 4,449 type 2 diabetic patients. The independent correlates of UACR were analysed.

Results

Independent correlates of UACR during baseline were (in descending order): night-time systolic BP (r s = 0.19); HbA1c (r s = 0.18); mean 24 h systolic BP (r s = 0.16); fasting blood glucose (r s = 0.16); night-time diastolic BP (r s = 0.12); office systolic BP, sitting (r s = 0.11), standing (r s = 0.10); estimated GFR (r s = 0.10); heart rate, sitting (r s = 0.10); haemoglobin (r s = −0.10); triacylglycerol (r s = 0.09); and uric acid (r s = −0.08; all p ≤ 0.001). Significantly higher albumin excretion rates were found for the following categorical variables: higher waist circumference (more marked in men); presence of the metabolic syndrome; smoking (difference more marked in males); female sex; antihypertensive treatment; use of amlodipine; insulin treatment; family history of diabetes; and family history of cardiovascular disease (more marked in women).

Conclusions/interpretation

Although observational correlations do not prove causality, in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients the albumin excretion rate is correlated with many factors that are potentially susceptible to intervention.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov ID no.: NCT00185159

Funding:

This study was sponsored by Daichii-Sankyo.

Keywords: Albuminuria, Diabetes, Diabetic nephropathy, Epidemiology, Hypertension, Proteinuria

Introduction

In both diabetic and non-diabetic patients, albuminuria has been recognised as an important renal and cardiovascular risk factor [1]. Although, using chemical methods, albuminuria had been detected in patients without primary renal disease more than 100 years ago [2], it was only after the introduction of immune detection methods [3] and the recognition that albuminuria is a predictor of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes [4, 5] that there was an explosive growth of information in this field.

The issue whether there is a safe threshold value of albuminuria has recently provoked intense discussion, mainly because in both non-diabetic [6] and diabetic [7] patients, urinary albumin concentrations in the upper normal range have been found to predict both cardiovascular [6] and renal plus cardiovascular events [7] in high risk [6] and low risk [8] populations. For these and other reasons it has been proposed by some authors to abandon microalbuminuria as a diagnostic category and to treat urinary albumin excretion (UAE) as a continuous variable, much like BP or serum cholesterol concentration [9].

A great number of past and recent studies have evaluated the evolution of UAE from normoalbuminuria to microalbuminuria and its correlates in adolescent [10–12] and adult [13, 14] type 1 diabetic patients. Information on type 2 diabetic patients is scarcer and is available only for some small cohorts [15].

The ROADMAP (Randomised Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention) Study [16] started in 2004 and provided a unique opportunity to investigate the factors which correlate with albumin excretion rates across the range of normoalbuminuric values in a large cohort of type 2 diabetic patients. Knowledge of these factors is of interest because albuminuria is correlated with cardiovascular and renal risk. It is the goal of the ROADMAP Study to provide further information on the selection of strategies for primary prevention of diabetic nephropathy.

In normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients, it has already been shown that an ACE inhibitor reduces the risk of de novo onset of microalbuminuria [17], but, as recently emphasised in a Cochrane review [18], there is a deficit of information on angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). The aim of the ROADMAP study is to provide evidence of whether or not it is possible to prevent the development of microalbuminuria by administration of the ARB olmesartan medoxomil.

In the present study, we analysed the baseline albuminuria levels in the ROADMAP cohort and determined which factors correlate with the degree of albuminuria within the so-called normoalbuminuric range.

Methods

The design of the ROADMAP Study has been described in detail previously [16]. In the following details relating to the baseline data will be briefly summarised.

Study design and organisation

ROADMAP is a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre phase 3 study that is being conducted in 262 collaborating centres in 19 European countries. The study protocol, which complies with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, has been approved by the relevant ethics committee at each participating centre. Written informed consent was required from each patient before enrolment in the trial.

Study population

The study has recruited 4,449 white patients (2,054 male and 2,395 female; age range, 18–75 years) with: type 2 diabetes (fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or treatment for diabetes); normoalbuminuria (≤35 mg [women] or ≤25 mg [men] albumin/g urinary creatinine); and at least one additional cardiovascular risk factor, including a lipid disorder defined as >5.2 mmol/l cholesterol or statin treatment, HDL-cholesterol <1.04 mmol/l, triacylglycerol >1.70 mmol/l, high systolic BP (SBP) (≥130 mmHg) and diastolic BP (DBP) (≥80 mmHg) or antihypertensive medication, obesity (BMI ≥ 28 m2/kg), high waist circumference (>102 cm [men], >88 cm [women]) or smoking more than five cigarettes per day.

Exclusion criteria included documented renal and/or renal–vascular disease, estimated GFR (eGFR) <60 ml min−1 m−2, recent cardiovascular event, severe hypertension (SBP > 200 mmHg and/or DBP > 110 mmHg) and recent (<26 weeks) treatment with ARBs or ACE inhibitors. Patient recruitment commenced in 2004 and was completed in the first half of 2006.

Office BP measurements were performed between 06:00 and 11:00 hours as trough readings and made three times in the sitting position (with mean calculated) and once standing, using standardised oscillometric OMRON HEM-907 BP monitors (Omron, Stuttgart, Germany).

In 1,234 patients, 24 h ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) was performed at baseline visit, using BOSO TM-2430 ambulatory BP measurement devices (Boso, Jungingen, Germany). BP was recorded for a 24 h period. During the day (07:00–22:00 hours) measurements were performed every 15 min and during the night (22:00–07:00 hours) every 30 min.

The urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) and all other laboratory values were determined in a central laboratory (CRL-Medinet, Breda, the Netherlands) within 24 h after obtaining the urine and blood samples from the patient. Urinary albumin was measured using immunoturbidimetry (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

In a screening visit the potential eligibility for the study was established by determining the UACR by morning spot urine testing. After a pre-randomisation phase (maximum duration 4 weeks) during which normoalbuminuria was confirmed by two additional independent morning spot urine tests. For the analysis of baseline values the average of three UACR spot urine samples was used.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were analysed by the following descriptive statistics: for dichotomous and categorical variables absolute and relative frequencies (counts and percents) were calculated, whereby the denominator for per cents is defined as the number of patients with non-missing values.

Comprehensive data summaries were performed by means of sample characteristics for all continuous variables (n; missing n; arithmetic mean; SD; minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, maximum and geometric mean if appropriate).

Correlations with albuminuria at screening were calculated for continuous variables by means of Spearman rank correlation coefficients (univariate and multivariate analysis; multivariate regression model with stepwise selection for loge albumin/creatinine ratio) and for categorical variables by means of a Wilcoxon rank sums test (two-sided test, normal approximation of test statistics of this non-parametric test).

|

where PCr is serum creatinine measured in micromole per litre.

Results

Patient data at baseline

The baseline data are summarised in Table 1. A total of 4,449 type 2 diabetic patients were included in the study: 90.3% of the patients had hypertension, defined as a BP > 130/80 mmHg or antihypertensive treatment; 67.5% of patients were receiving antihypertensive treatment; 71.6% had lipid disorders. A high percentage of the patients were overweight and had central obesity.

Table 1.

Patient data at baseline

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| Total | 4,449 |

| Women, n (%) | 2,395 (53.8) |

| Age (years) | 57.7 ± 8.7 (58) |

| Known duration of diabetes (years) | 6.1 ± 6.0 (4.3) |

| Insulin treatment, n (%) | 821 (18.5%) |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agents | 3,752 (84.3) |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6 ± 1.6 (7.3) |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/l) | 9.1 ± 3.1 (8.4) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 140.8 ± 16.3 (140.0) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 84.0 ± 9.8 (84.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.0 ± 4.9 (30.5) |

| Central obesity, n (%)a | 3,181 (71.5) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%)b | 3,528 (79.3) |

| Current smokers, n (%)c | 831 (18.7) |

| eGFR (ml min−1 1.73 m−2) | 84.5 ± 16.8 (83.8) |

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 142 ± 13 (141) |

| Triacylglycerol (mmol/l) | 2.1 ± 1.3 (1.8) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.3 ± 1.1 (5.2) |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.2 ± 0.9 (3.1) |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.2 ± 0.3 (1.2) |

| Uric acid (µmol/l) | 321 ± 83 (321) |

| Known family history of diabetes, n (%) | 2,194 (49.3) |

| Known family history of CV events, n (%) | 1,678 (37.7) |

Values are means±SD (median) for continuous variables, or n (%) for categorical variables

aHigh waist circumference: >102 cm in men, >88 cm in women

bNCEP ATP III criteria

cMore than five cigarettes per day

CV, cardiovascular

Albuminuria at screening

In these patients the albumin/creatinine ratio in morning spot urine tests was loge normally distributed with a median of 0.44 mg/mmol creatinine (interquartile range 0.28–0.81; Fig. 1). In men, the median was 0.41 mg/mmol creatinine (interquartile range 0.24–0.75, mean 0.58 ± 0.78, geometric mean 0.43) and in women the median was 0.46 mg/mmol creatinine (interquartile range 0.31–0.88, mean 0.67 ± 0.54, geometric mean 0.52).

Fig. 1.

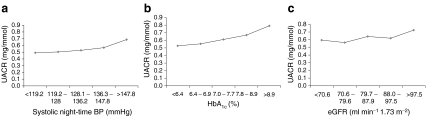

Relationship of UACR with quintiles of night-time SBP (a), HbA1c (b) and eGFR (c)

The median uncorrected albumin concentration in morning spot urine tests in men was 4.2 mg/ml (interquartile range 2.0–7.7, mean 6.11 ± 10.26, geometric mean 4.2) and in women 3.2 mg/ml (interquartile range 1.5–6.2, mean 5.04 ± 5.27, geometric mean 3.6). The albumin/creatinine ratio is higher in women, as expected, because of the higher UACR exclusion values for female patients (≥3.96 mg/mmol) than for men (≥2.83 mg/mmol); however the absolute uncorrected albumin concentration is lower in women as a result of markedly lower urinary creatinine concentrations in women.

Ambulatory BP (Holter monitoring) in a sub-cohort of patients

The values of 24 h ABPM prior to taking the study medication were available in a sub-cohort of 1,234 of the 4,449 patients (567 men, 667 women). The values of different ABPM variables are given in Table 2. The average BP was 139.6/81.5 mmHg, confirming the results obtained in the office BP cohort.

Table 2.

Twenty-four hour data from ABPM

| Reading | Value (n = 1,234) |

|---|---|

| 24 h SBP | 139.6 ± 15.4 (138.9) |

| 24 h DBP | 81.5 ± 8.1 (81.1) |

| Daytime SBP | 143.6 ± 15.6 (143.4) |

| Daytime DBP | 84.3 ± 8.5 (83.8) |

| Night-time SBP | 133.8 ± 17.9 (131.7) |

| Night-time DBP | 77.4 ± 9.4 (6.9) |

| 24 h pulse pressure | 58.1 ± 10.3 (57.6) |

| Daytime pulse pressure | 59.3 ± 10.7 (59.0) |

| Night-time pulse pressure | 56.5 ± 11.7 (55.1) |

| Mean daytime SBP minus mean night-time SBP | 9.7 ± 12.1 (10.0) |

| Mean daytime DBP minus mean night-time DBP | 6.9 ± 7.3 (6.9) |

Values are means ± SD (median)

Correlation of albuminuria with continuous variables

The correlations for different continuous variables were calculated. We found a correlation with several commonly measured variables. The strongest correlation was observed for night-time SBP and HbA1c levels (Table 3 and Fig. 1a, b). eGFR was correlated as well, but the correlation was moderate (Fig. 1c). Multivariate analysis in the total cohort and in the sub-cohort of patients with ABPM confirmed that HbA1c and SBP had the best correlation with UACR (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients (r s) by univariate analysis with UACR (morning spot urine) as the dependent variable

| Variable | r s | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Night-time SBPa | 0.19 | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Mean 24 h SBPa | 0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose | 0.16 | <0.0001 |

| Night-time DBPa | 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Mean 24 h DBP* | 0.11 | 0.0001 |

| Office SBP (sitting) | 0.11 | <0.0001 |

| Office SBP (standing) | 0.10 | <0.0001 |

| eGFR | 0.10 | <0.0001 |

| Haemoglobin | −0.10 | <0.0001 |

| Triacylglycerols | 0.09 | <0.0001 |

| Office pulse pressure (amplitude) | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Uric acid | −0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of diabetes | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Office DBP (standing) | 0.07 | <0.0001 |

| Office DBP (sitting) | 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| BMI | 0.06 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol | 0.05 | 0.0014 |

No univariate Spearman correlation to: ABPM SBP variability (maximum−minimum during 24 h period), LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol or neutrophil counts

aABPM (Holter monitoring) data in sub-cohort of 1,234 patients

Table 4.

Multivariate regression model with stepwise selection of loge UACR

| Order | Variable | Partial R 2 | p value | Regression coefficienta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HbA1c | 0.0344 | <0.0001 | 0.05419 |

| 2 | Sex (females higher) (coded 0=male, 1=female) | 0.0137 | <0.0001 | 0.16693 |

| 3 | Office SBP (sitting) | 0.0126 | <0.0001 | 0.00422 |

| 4 | eGFR | 0.0123 | <0.0001 | 0.00574 |

| 5 | Triacylglycerols | 0.0047 | <0.0001 | 0.03430 |

| 6 | Haemoglobin | 0.0034 | <0.0001 | −0.00420 |

| 7 | Family history of diabetes | 0.0028 | 0.0002 | −0.06626 |

| 8 | Age | 0.0023 | 0.0010 | 0.00533 |

| 9 | Heart rate (sitting) | 0.0020 | 0.0021 | 0.00313 |

| 10 | Antihypertensive treatment | 0.0021 | 0.0015 | 0.08129 |

| 11 | Smoking status (ordinally coded 0=non-smoker, 1=ex-smoker, 2=smoker) | 0.0019 | 0.0027 | 0.04451 |

| 12 | Fasting glucose | 0.0009 | 0.0326 | 0.01034 |

| 13 | HDL-cholesterol | 0.0009 | 0.0409 | −0.07907 |

| 14 | Family history of CVD | 0.0008 | 0.0436 | −0.04354 |

aVariables with a positive sign for the regression coefficient, increasing albuminuria; with a negative sign, decreasing albuminuria

CVD, cardiovascular disease

Table 5.

Multivariate regression model with stepwise selection of loge UACR in the sub-cohort with ABPM (n = 1,234)

| Order | Variable | Partial R 2 | p value | Regression coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HbA1c | 0.0484 | <0.0001 | 0.08013 |

| 2 | ABPM night-time SBP | 0.0267 | <0.0001 | 0.00405 |

| 3 | Office SBP (sitting) | 0.0103 | 0.0002 | 0.00484 |

| 4 | Family history of diabetes | 0.0094 | 0.0004 | −0.14284 |

| 5 | Antihypertensive treatment | 0.0062 | 0.0037 | 0.14548 |

| 6 | eGFR | 0.0061 | 0.0039 | 0.00405 |

| 7 | Sex (females higher) (coded 0=male, 1=female) | 0.0047 | 0.0113 | 0.11502 |

| 8 | Duration of type 2 diabetes | 0.0042 | 0.0159 | 0.00063 |

| 9 | Standing minus sitting office DBP | 0.0031 | 0.0397 | 0.00768 |

| 10 | Standing minus sitting office heart rate | 0.0031 | 0.0372 | −0.00815 |

Correlation of albuminuria with categorical variables

The correlations for a set of categorical variables were calculated. A highly significant correlation existed between the degree of UACR and variables of the metabolic syndrome, BP and female sex (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation of UACR with categorical variables

| Variable | Effect on albuminuria | p valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Increased waist circumference | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Men >102 cm | Higher | 0.0171 |

| Women >88 cm | Higher | NS |

| Metabolic syndrome (yes) (NCEP-ATP-III) | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Family history of diabetes | Lower | 0.0068 |

| Family history of CVD | Lower | 0.0252 |

| Antihypertensive medication | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Amlodipine treatment | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Insulin treatment | Higher | 0.0280 |

| Office SBP >140 mmHg or DBP >90 mmHg | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Office SBP >130 mmHg or DBP >85 mmHg | Higher | <0.0001 |

| Smoking: male ex-smokers vs non-smokers and smokers | Higher | 0.0002 |

Categorical factors that were not significant included: family history of renal disease, family history of hypertension, current use of aspirin or statins, ethnic origin, smoking in women

aTwo-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test; normal approximation of test statistics

CVD, cardiovascular disease

Night-time BP as determinant of albuminuria

As the night-time BP showed a high correlation in the uni- and multivariate analysis (ABPM sub-cohort), the effect of BP changes from day to night were analysed. The mean UACR was 0.63 ± 0.53 mg/mmol in patients with an increased BP during the night and 0.54 ± 0.44 mg/mmol in patients with an inverted BP profile (i.e. increased BP during the day; Table 7).

Table 7.

UACR (mg/mmol) in patients (ABPM sub-cohort) with night-time SBP lower or higher than daytime SBP

| Data | SBP at night ≤SBP in day (n = 1,001) | SBP at night ≥SBP in day (n = 229) | Total (n = 1,230) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | 0.54 ± 0.44 | 0.63 ± 0.53a | 0.55 ± 0.46 |

| Q1/median/Q3 | 0.26/0.37/0.68 | 0.31/0.45/0.82 | 0.27/0.42/0.68 |

| Minimum to maximum | 0.11–3.42 | 0.11–4.03 | 0.11–4.03 |

a p = 0.0076 vs SBP at night ≤SBP in day

Q, quartile

Discussion

This large study comprised 4,449 relatively young type 2 diabetic patients (mean age 57.7 years, range 28–75) with an average duration of diabetes of 6.1 years. At baseline they had moderately controlled median BP (140/84 mmHg), but attenuated lowering of night-time SBP (−6.8%). The median HbA1c was relatively low (7.3%), but the cardiovascular risk factor profile was high (67.0% had ≥4 cardiovascular risk factors).

As evaluated by Spearman correlation coefficient analysis, the factors most strongly correlated with the variation in albuminuria within the normoalbuminuric range comprised BP variables, most strongly, night-time SBP and further BP indices: mean 24 h SBP, night-time SBP, office SBP in men (but not in women), mean 24 h DBP and office DBP as well as pulse pressure as an index of vascular stiffness [19].

The BP data are in good agreement with previous reports in smaller cohorts reported in the literature. In type 1 diabetes, higher night-time SBP predicted the onset of microalbuminuria [20] and the occurrence of cardiovascular events [21], respectively. Similarly in type 2 diabetes, attenuated dipping and elevated night-time BP are frequent [22]. Night-time SBP was higher than daytime SBP in adult diabetic patients who developed microalbuminuria [22]. Attenuated dipping was also found to be correlated with coronary events [23]. In one relatively small recent study, however, the correlation of albuminuria to night-time BP dipping was less tight than to absolute BP [24]. Furthermore, masked hypertension is also correlated with albuminuria [25]. In the present study, the ABPM sub-cohort with higher night-time than daytime BP had significantly higher (p = 0.0076 by Wilcoxon rank sum test) albumin excretion compared with patients with lower night-time than daytime BP.

In a very small sample of patients with type 2 diabetes, a recent report found that pulse pressure (as a potential indicator of vascular stiffness) was related to albumin excretion [26]. This finding is confirmed in our much larger cohort. The present study, in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients, extends the findings on pulse pressure in the large cross-sectional study in microalbuminuric and proteinuric type 2 diabetic patients by Tanaka et al. [27]: the present study documents that a relationship between pulse pressure and albuminuria is found even in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients. Tanaka et al. had also noted a correlation with aortic pulse wave velocity and carotid intima–media thickness. In a small sample of normo- and microalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients, albuminuria was correlated with markers of endothelial cell dysfunction [28], and this may explain, at least in part, this correlation to pulse wave velocity.

In the present study albuminuria was also significantly correlated with indices of glycaemic control, i.e. HbA1c, fasting glucose and duration of diabetes, as well as insulin treatment as a categorical variable. Individuals requiring insulin treatment and individuals with longer duration of diabetes presumably have more advanced renal lesions.

Furthermore, BMI and the categorical variables of elevated waist circumference and the metabolic syndrome according to NCEP-ATP-III criteria [29] were correlated with albuminuria as well. This observation is again in line with previous communications and the observation that UAE reflects insulin resistance [30].

In the general non-diabetic population [31] and in essential hypertension [32] impaired glucose tolerance increases the risk of microalbuminuria. Even sub-diabetic glycaemia increased the risk of microalbuminuria in the ‘Framingham Offspring’ study [33]. In the UKPDS study, the patients who presented with type 2 diabetes and had lower glycaemia had also a lower risk of albuminuria [34]. In the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study [35], the prevalence of albuminuria increased significantly with increasing glycaemia. It is particularly postprandial glycaemia, not measured in the present study, which is best correlated with albuminuria [36], so that the overall impact of glycaemia may even have been somewhat underestimated in the present study.

In the general population the metabolic syndrome is associated with both microalbuminuria and chronic kidney disease [37] and the same is observed in hypertensive patients [32].

In the general non-diabetic population, waist circumference, an index of visceral obesity, also predicted higher albumin excretion [38]. In type 1 [39] and type 2 diabetes as well [40], waist circumference had been found to be a predictor of microalbuminuria.

In the above study a positive relationship was found between albuminuria and estimated GFR [41], indicating that hyperfiltration presumably plays a role in the pathogenesis of high normal albuminuria in type 2 diabetes. A note of caution is appropriate, however, since in diabetic patients eGFR is not a reliable indicator of true GFR, at least in individual patients [42].

In agreement with reports in the literature on patients with type 1 [43] and type 2 diabetes [44], albuminuria was also correlated, although not markedly, to triacylglycerol, total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol.

A recent report found a positive correlation between uric acid and albuminuria in male type 2 diabetic patients [45] in whom confounding factors had been excluded, such as use of allopurinol, diuretics or alcohol consumption. In the present ROADMAP Study the correlation was negative and this persisted even when adjusted for the potential confounding effect of alcohol use.

The use of and presumably need for antihypertensive medication, particularly amlodipine, was positively related to albuminuria. The correlation with antihypertensive medication may be an example of confounding by indication, i.e. that patients with more severe and more advanced disease required antihypertensive medication and had also higher rates of albuminuria. The significant effect of amlodipine, however, may be more complex. At the time of screening the patients had not yet received, or were off, renin–angiotensin receptor blockers for at least 6 months.

The strength of our study is that we analysed UACR in a large sample of type 2 diabetic patients without kidney disease (no microalbuminuria, eGFR > 60 ml min−1 1.73 m−2). As the inclusion and exclusion criteria were fulfilled by the majority of the screened patients, this study population is representative of the majority of type 2 diabetic patients. Moreover, our data on UACR are based on the measurement of albuminuria in three morning spot urines.

It should be noted that only 10% of the total variance of the UACR could be explained by the degree of blood glucose control, BP variables, lipids and age. Verhave et al. analysed the correlation of albumin excretion (UAE) with cardiovascular risk factors in 7,841 patients of the PREVEND cohort [45]. In their cohort, taken from the general population, only 3.5% had diabetes and 14% microalbuminuria at baseline. They found a correlation between UAE and male sex, age, SBP, DBP, fasting glucose levels, BMI, smoking and creatinine clearance. In a multivariate analysis only 22% of the variance of UAE could be explained by these variables. In the PREVEND cohort the strongest correlation existed between glucose level and UAE. Since all patients in the ROADMAP Study had diabetes, this observation might explain why we were only able to explain 10% of the variance of the loge UACR. The relatively modest correlation may also be because of the fact that most of the patients were in the low normoalbuminuric range at baseline. In this low range the variability is known to be relatively high. The intra-individual variability of the three repeated UACR measurements was 55% in the ROADMAP cohort.

Therefore, the correlation observed points more to the direction (thus providing a potential target of treatment) rather than reflecting the magnitude of the relationship. The identified variables correlate not only with the degree of albuminuria within the normoalbuminuric range but might also be predictors for the development of microalbuminuria (Table 8).

Table 8.

Determinants of baseline values for the development of microalbuminuria

| Value | Study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct [49]a | Hope [50]b | Benedict [17]c | |

| Age | n.d. | + | n.d. |

| Male sex | + | + | n.d. |

| SBP | n.d. | + | = |

| DBP | n.d. | = | = |

| Pulse pressure | n.d. | n.d. | = |

| BMI kg/m2 | n.d. | + | n.d. |

| Cholesterol | n.d. | = | n.d. |

| Low HDL-cholesterol | n.d. | = | n.d. |

| Smoking | n.d. | + | n.d. |

| Baseline UAE | + | n.d. | n.d. |

| Retinopathy | + | n.d. | n.d. |

| HbA1c | + | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d., not determined; +, positive correlation; =, no significant correlation

aThe Diabetes Incidence after REnal Transplantation (DIRECT) Study: 3,326 and with type 1 and 1,905 type 2 diabetes were followed for 4.7 years

bThe Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study: 9,043 patients with and without type 2 diabetes were followed for 4.5 years and determinants of albuminuria assessed

cThe Bergamo NEphrologic Diabetes Complications Trial (BENEDICT): 1,204 patients with type 2 diabetes were followed for 3.6 years and risk factors for the development of microalbuminuria analysed

Studies in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients have additional limitations. First, on the one hand in diabetic patients albuminuria is certainly correlated with the severity of glomerular lesions [46], but the correlation is not strict, particularly in type 2 diabetes [47]. Albuminuria therefore does not permit conclusions with respect to diabetic glomerular lesions. On the other hand, diabetic glomerular lesions may even precede the onset of albuminuria [11].

Second, microalbuminuria is present in 16% of patients at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes [47]. Microalbuminuria frequently precedes the onset of overt type 2 diabetes [35] and one potential explanation may be the relatively strong correlation between albuminuria and the metabolic syndrome, a prediabetic state with insulin resistance [48].

In conclusion, the present baseline data of the ROADMAP Study suggest that albuminuria is a continuous variable, and that even in normoalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients albumin excretion rates are correlated with a number of factors which are potentially susceptible to therapeutic intervention, although certainly correlation does not necessarily imply causality.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Daichii-Sankyo. The statistical support of L. Pecen (Institute of Computer Science Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic) is gratefully acknowledged.

Duality of interest

All authors have received honoraria from Daichii-Sankyo.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- ABPM

Ambulatory BP monitoring

- ARB

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- DBP

Diastolic BP

- eGFR

Estimated GFR

- ROADMAP

Randomised Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention (Study)

- SBP

Systolic BP

- UACR

Urinary albumin/creatinine ratio

- UAE

Urinary albumin excretion

Footnotes

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1623-1

References

- 1.Lambers Heerspink HJ, Brinkman JW, Bakker SJ, Gansevoort RT, de Zeeuw D. Update on microalbuminuria as a biomarker in renal and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:631–636. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000247496.54882.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senator H. Albuminuria in health and disease. London: The New Sydenham Society; 1884. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mogensen CE. Urinary albumin excretion in diabetes. Lancet. 1971;2:601–602. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mogensen C. Microalbuminuria predicts clinical proteinuria and early mortality in maturity-onset diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:356–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198402093100605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viberti GC, Hill RD, Jarrett RJ, Argyropoulos A, Mahmud U, Keen H. Microalbuminuria as a predictor of clinical nephropathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1982;1:1430–1432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Olsen MH, et al. Albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE Study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:901–906. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rachmani R, Levi Z, Lidar M, Slavachevski I, Half-Onn E, Ravid M. Considerations about the threshold value of microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus: lessons from an 8-year follow-up study of 599 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;49:187–194. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(00)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnlov J, Evans JC, Meigs JB, et al. Low-grade albuminuria and incidence of cardiovascular disease events in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic individuals: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112:969–975. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Time to abandon microalbuminuria? Kidney Int. 2006;70:1214–1222. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallego PH, Gilbey AJ, Grant MT, et al. Early changes in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure are associated with high normal albumin excretion rate in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18:879–885. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrin NE, Torbjornsdotter TB, Jaremko GA, Berg UB. Follow-up of kidney biopsies in normoalbuminuric patients with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1004–1013. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone ML, Craig ME, Chan AK, Lee JW, Verge CF, Donaghue KC. Natural history and risk factors for microalbuminuria in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2072–2077. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giorgino F, Laviola L, Cavallo Perin P, Solnica B, Fuller J, Chaturvedi N. Factors associated with progression to macroalbuminuria in microalbuminuric type 1 diabetic patients: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1020–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovind P, Tarnow L, Rossing P, et al. Predictors for the development of microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria in patients with type 1 diabetes: inception cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:1105–1109. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38070.450891.FE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada T, Komatsu M, Komiya I, et al. Development, progression, and regression of microalbuminuria in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes under tight glycemic and blood pressure control: the Kashiwa Study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2733–2738. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haller H, Viberti GC, Mimran A, et al. Preventing microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes: rationale and design of the Randomised Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:403–408. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000202820.56201.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruggenenti P, Fassi A, Ilieva AP, et al. Preventing microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1941–1951. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strippoli GF, Craig M, Navaneethan SD, Craig JC (2006) Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists for preventing the progression of diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006, CD006257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Strain WD, Chaturvedi N, Dockery F, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in Europeans and African Caribbeans with type 2 diabetes cannot be accounted for by conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lurbe E, Redon J, Kesani A, et al. Increase in nocturnal blood pressure and progression to microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:797–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Astrup AS, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Pietraszek L, Riis Hansen P, Parving HH. Improved prognosis in type 1 diabetic patients with nephropathy: a prospective follow-up study. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1250–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afsar B, Sezer S, Elsurer R, Ozdemir FN. Is HOMA index a predictor of nocturnal nondipping in hypertensives with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus? Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:133–139. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3280b08379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamura K, Tsurumi Y, Sakai M, et al. A possible relationship of nocturnal blood pressure variability with coronary artery disease in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2007;29:31–42. doi: 10.1080/10641960601096760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano S, Ito T, Furuya K, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure level rather than dipper/nondipper status predicts vascular events in type 2 diabetic subjects. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:647–656. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leitao CB, Canani LH, Kramer CK, Boza JC, Pinotti AF, Gross JL. Masked hypertension, urinary albumin excretion rate, and echocardiographic parameters in putatively normotensive type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1255–1260. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anan F, Masaki T, Umeno Y, et al. Correlations of urinary albumin excretion and atherosclerosis in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka M, Babazono T, Takeda M, Iwamoto Y. Pulse pressure and chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:345–352. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen ST, Jeppesen P, Frederiksen CA, et al. Endothelial dysfunction, ambulatory pulse pressure and albuminuria are associated in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabet Med. 2007;24:911–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Executive Summary of the Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (2001). JAMA 285:2486–2497 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Parvanova AI, Trevisan R, Iliev IP, et al. Insulin resistance and microalbuminuria: a cross-sectional, case-control study of 158 patients with type 2 diabetes and different degrees of urinary albumin excretion. Diabetes. 2006;55:1456–1462. doi: 10.2337/db05-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franciosi M, Pellegrini F, Sacco M, et al. Identifying patients at risk for microalbuminuria via interaction of the components of the metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional analytic study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:984–991. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascual JM, Rodilla E, Gonzalez C, Perez-Hoyos S, Redon J. Long-term impact of systolic blood pressure and glycemia on the development of microalbuminuria in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:1125–1130. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000167151.52825.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meigs JB, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Nathan DM, Rifai N, Wilson PW. Longitudinal association of glycemia and microalbuminuria: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:977–983. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colagiuri S, Cull CA, Holman RR. Are lower fasting plasma glucose levels at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes associated with improved outcomes?: U.K. prospective diabetes study 61. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1410–1417. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapp RJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, et al. Albuminuria is evident in the early stages of diabetes onset: results from the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:792–798. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(04)01079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XL, Lu JM, Pan CY, Tian H, Li CL. A comparison of urinary albumin excretion rate and microalbuminuria in various glucose tolerance subjects. Diabet Med. 2005;22:332–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, et al. The metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease in U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:167–174. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnet F, Marre M, Halimi JM, et al. Waist circumference and the metabolic syndrome predict the development of elevated albuminuria in non-diabetic subjects: the DESIR Study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1157–1163. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226206.03560.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer IH, Sibley SD, Kestenbaum B, et al. Central obesity, incident microalbuminuria, and change in creatinine clearance in the epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:235–243. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tseng CH. Waist-to-height ratio is independently and better associated with urinary albumin excretion rate than waist circumference or waist-to-hip ratio in Chinese adult type 2 diabetic women but not men. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2249–2251. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function—measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossing P, Rossing K, Gaede P, Pedersen O, Parving HH. Monitoring kidney function in type 2 diabetic patients with incipient and overt diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1024–1030. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas MC, Rosengard-Barlund M, Mills V, et al. Serum lipids and the progression of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:317–322. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tseng CH. Lipid abnormalities associated with urinary albumin excretion rate in Taiwanese type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1547–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tseng CH. Correlation of uric acid and urinary albumin excretion rate in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Taiwan. Kidney Int. 2005;68:796–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drummond K, Mauer M. The early natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: II. Early renal structural changes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1580–1587. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fioretto P, Mauer M. Histopathology of diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mykkanen L, Zaccaro DJ, Wagenknecht LE, Robbins DC, Gabriel M, Haffner SM. Microalbuminuria is associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic subjects: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes. 1998;47:793–800. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bilous R, Chaturvedi N, Sjolie AK, et al. Effect of candesartan on microalbuminuria and albumin excretion rate in diabetes: three randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(11–20):W3–W4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mann JF, Gerstein HC, Yi QL, et al. Development of renal disease in people at high cardiovascular risk: results of the HOPE randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:641–647. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000051594.21922.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]