Abstract

Many RNA viruses exist as a cloud of closely related sequence variants called a quasispecies, rather than as a population of identical clones. In this article, we explain the quasispecies nature of RNA viral genomes, and briefly review the principles of quasispecies dynamics and the differences with classical population genetics. We then discuss the current methods for quasispecies analysis and conclude with the biological implications of this phenomenon, focusing on the hepatitis C virus.

Keywords: HCV, quasispecies, RNA, consensus sequence, viral persistence, compartmentalization, interferon resistance, diversity, complexity

General Introduction

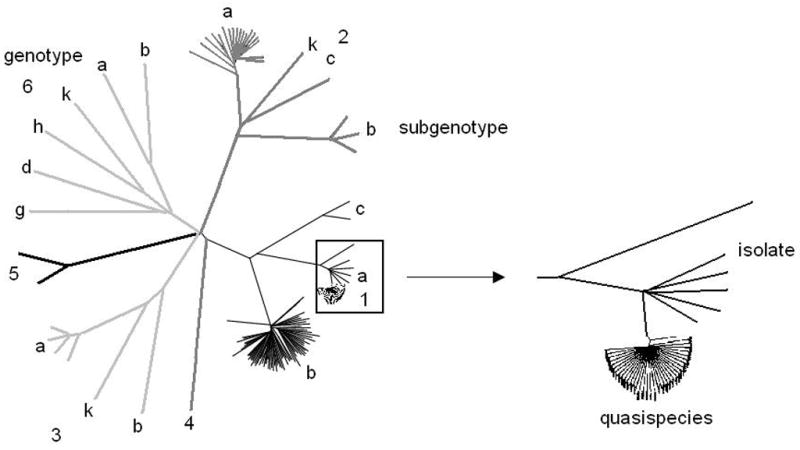

Due to an error prone replication mechanism, and the ability to survive mutation, hepatitis C virus (HCV) evolves rapidly and has extensive sequence diversity (Choo et al., 1991; Domingo et al., 1985). Viral isolates are divided into six major groups called genotypes, and within the genotypes there are many subgenotypes. Between genotypes there is 66%–69% sequence identity among isolates at the nucleotide level across the entire genome, 77%–80% between subtypes, and 91%–99% within a given subtype (Bukh et al., 1995; Simmonds, 1995). Within an infected individual, HCV circulates as a set of closely related variants referred to collectively as quasispecies (Domingo et al., 1985; Martell et al., 1992; Steinhauer and Holland, 1987b), rather than as a clonal population (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HCV sequences have been classified into six major genotypes with approximately 65% sequence identity. Within each genotype, sequences are further classified into subtypes with 78% sequence identity. Different isolates within the same subtype share 91–99% sequence identity. Within a host, HCV circulates as a population of very closely related, but not identical, variants called a quasispecies. Genotypes are denoted by numbers (1–6) and subgenotypes by lower case letters.

The sequence heterogeneity in the quasispecies is a common feature of viruses that have a replication intermediate composed of RNA. One of the first physical demonstrations of the quasispecies nature of RNA viruses was revealed during the sequencing of the RNA phage QB by T1-finger printing (Domingo et al., 1978). After re-cloning the phage from a single plaque, the observed fingerprint of the new isolate deviated from the parental clone. When this process was repeated, several different fingerprint patterns were observed that deviated from the original pattern and from each other, usually by one nucleotide, but occasionally by two or more nucleotides. After serial passages of these clones, the original “wildtype” fingerprint pattern was restored. The investigators concluded that the phage population was heterogeneous, but that there was a defined “average” sequence for the population. Today, the existence of quasispecies has been shown in a number of viruses. The biological implications of this phenomenon have been demonstrated in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) (Wain-Hobson, 1992), hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Forns et al., 1999), foot-and-mouth disease virus (Domingo et al., 1992), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (Steinhauer et al., 1989), polio (Vignuzzi et al., 2006) and others.

The rapid mutation of such viruses is due to the error prone nature of RNA dependent RNA polymerases that generally lack the proof reading ability of DNA polymerases associated with 3′ -> 5′ exonuclease activity (Duarte et al., 1994; Kohlstaedt et al., 2009; Steinhauer et al., 1992) leading to mutation rates of 1 mutation per 103 to 105 bases copied per replication cycle (Drake and Holland, 1999). In conjunction with small genomic size, such viruses may incorporate one point mutation with each round of replication (Drake and Holland, 1999). The mutations are frequently well tolerated, allowing mutants to survive. As a result, these organisms can exist in a host as a cloud of closely related sequence variants, differing by as little as one nucleotide from a population average sequence. Collectively these variants are referred to as quasispecies.

Many viral factors, such as the error rate of the polymerase, short replication cycle, and compact genome contribute to the generation of the cloud of variants. Additionally, host factors and immune responses exert a selection pressure that contributes to evolution and diversification of the quasispecies. The variation between individual viral genomes in vivo is thought to contribute to persistence, resistance to treatment, tissue tropism, and the failure of experimental vaccines (Holland et al., 1992).

Quasispecies Theory

To explain the adaptability of self replicating RNA elements, Eigen and Schuster first developed mathematical models of quasispecies behavior, based on principles of evolution and information theory (Eigen and Schuster, 1979). The equations describing quasispecies dynamics are out of the scope of this review, but the interested reader is referred to (Bull et al., 2005; Eigen, 1996; Eigen, 2000; Eigen and Schuster, 1979; Wilke, 2005). Quasispecies theory of RNA viruses differs from classical population genetics in a number of its fundamental assumptions about the nature of genomic replication. These include a high mutation rate of the genome, a small genome size, an extremely large (approaching infinite) population of organisms, and an equilibrium state where effects of mutations equal the effects of selection (Comas et al., 2005). According to quasispecies theory, under such conditions in a stable environment, one can ignore the effects of neutral mutations (mutations that neither hurt nor promote the fitness of a variant) and genetic drift that are assumed in classical population genetics (Eigen, 1987; Holmes and Moya, 2002; Jenkins et al., 2001).

In quasispecies theory, the frequency of a particular variant is dependent not only on its inherent fitness, but also on its relatedness to other variants. The closer a particular sequence is to other variants, the more likely that sequence will arise again independently as a result of mutations introduced into other variants by error prone replication. It follows that in a quasispecies, evolution and selection act on the population as a whole, rather than on individuals (Biebricher and Eigen, 2005; Eigen, 1987; Eigen, 1993; Eigen, 1996). Each variant contributes to the fitness of the population. Even a particularly fit variant, will be unable to maintain itself indefinitely in the population due to the high mutation rate leading to reversions of fitness. Studies of VSV in cell culture have demonstrated physically that having a population of closely related variants can allow an individual with low fitness to out-compete an individual of higher fitness, provided the high fitness species is a minor component of the population (de la Torre and Holland, 1990). This has been described as the triumph of the “mean” (average) over the fittest (Gomez and Cacho, 2001). Usually, there exists a dominant sequence that is most frequently represented in the population (Eigen, 1987; Eigen, 1993; Eigen, 1996; Nowak and May, 1992) although this may amount to as little as 10% of the population. Classically, the dominant sequence is assumed to be the one best adapted to the environment in which it was observed.

The applicability of quasispecies theory to the behavior of RNA viruses remains somewhat controversial among evolutionary biologists (Comas et al., 2005; Holmes, 2003; Holmes and Moya, 2002; Jenkins et al., 2001; Moya et al., 2000; Wilke, 2005). Specifically, some argue that in practice the main implication of quasispecies theory, that selection acts on the population rather than on the individual, is invalid because the effects of genetic drift can not be ignored. Furthermore, while sequencing studies have found that over half of the positions in a typical viral genome can be mutated and still lead to a viable offspring (Duarte et al., 1994), in practice, few nucleotide sites in the viral genome are truly neutral and many single mutations confer a lethal, non replicating phenotype. Synonymous sites in the genome have generally been the source of neutrally evolving positions. However, since selection on these sites might arise for reasons other than protein coding including codon bias of the host and restrictions imposed by RNA secondary structures, the effects of supposedly neutral mutations can not be ignored. Additionally, others argue that the mutation rate in RNA viruses is not sufficiently high to establish a population that can be accurately described by quasispecies theory. Studies using systems of “digital organisms,” computer models representing linear RNA viral sequences, suggest that the necessary mutation rates for stable quasispecies development are not attainable in nature (Comas et al., 2005).

Regardless of whether the kinetics of quasispecies theory applies to RNA viruses, their existence in a host as a cloud of related but not identical of viral variants has important biological implications.

Methods of quasispecies analysis

When analyzing a quasispecies, it is useful to begin by determining the consensus sequence of all variants in the population. Obtaining the consensus sequence is relatively straightforward. Viral RNA is isolated from a clinical specimen or from an experimental system, amplified by RT-PCR, and the amplicon is sequenced directly. Automated sequencing machinery typically selects the base that is most common in the amplicon at each position. If two or more bases are present with roughly equal frequencies at a particular position, the automated sequencing machinery may not be able to identify the single most common base. Review of the chromatogram accompanying the sequencing results is useful in resolving such discrepancies and in obtaining a rudimentary sense of the variation in the population.

Cloning and nucleotide sequencing

The sequencing of individual variants in the quasispecies is a multi-step and costly endeavor, but it can provide many details about the composition of the quasispecies. This process begins with amplification of the viral genome using primers that bind to highly conserved areas of the genome surrounding the region of interest. Sequence variations in the primer binding site may prevent the amplification of a minority of the population. The PCR product is cloned into a plasmid vector that can be used to transform bacteria. Transformed bacteria are plated at a low density to allow for the selection of individual colonies, which are assumed to be carrying only one plasmid and therefore only one viral variant. By retrieving and sequencing the plasmid DNA from an individual bacterial colony, one can obtain the sequence of a single variant.

In all reports of quasispecies sequencing, only a small fraction of the viral genome is sampled. Studies of translation in HCV often include analysis of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES), while investigations of viral entry and immune evasion typically focus on the envelope and hypervariable region (HVR1). The core, HVR1, and NS5A genes are often selected for analyses that predict IFN treatment outcomes. When analyzing a single gene or region, it is important to consider that downstream and/or upstream mutations may modulate the effects of mutations in the region of interest. Furthermore, the choice of region to study can greatly impact the conclusions, as demonstrated in studies by Farci and colleagues (described below) who reported an association between increased quasispecies complexity in the HVR1 and HCV disease progression, but did not find a similar association with other regions of the genome (Farci et al., 2000).

Opinions vary on the number of clones that need to be sequenced to appropriately investigate the quasispecies. For mutational frequency and entropy analysis, 20–100 clones per sample are recommended (Gretch and Polyak, 1997). It has been estimated that sequencing 99 clones of HVR1 will identify 95% of all variants present at a frequency of at least 3% in the population (McCaughan et al., 2003). Another estimate suggests 20 clones is sufficient to sample 95% of the major variants (those with at least 10% frequency in the population) (Gretch and Polyak, 1997), however most minor variants may be undetected, leaving out useful information (Gretch et al., 1996). It is important to consider the conservation of the gene or genomic region when deciding how many clones to sequence.

The recent development of massively parallel ultra-deep pyrosequencing has allowed investigators to sequence a much larger fraction of the quasispecies. This increase in genomes sampled comes at the expense of sequence coverage with reads of often less than 200 base pairs. Ultra-deep sequencing works by separating individual DNA molecules from the cDNA amplicon and attaching them to specialized beads. Local in-vitro amplification of each DNA molecule is performed in an emulsion, and beads are then loaded into wells on a plate for pyrosequencing. Light from the pyrosequencing reactions are recorded and used to determine the sequence of the input DNA molecules. This method allows rapid sequence determination of a large number of variants by eliminating the need to separate molecules by cloning in bacterial vectors (Eriksson et al., 2008; Margulies et al., 2005). Ultra-deep sequencing has been used to identify extremely minor variants in the quasispecies that may be related to the development of drug resistance in HIV infected patients (Hoffmann et al., 2007; Simen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2007) and is emerging as a technology for quasispecies analysis of HCV.

Nucleotide sequencing is essential to studies of transmission, phylogenetics, and outbreaks. During HCV transmission events, a small subset of the population in the initial host is transferred to the new host and then subjected to the pressures of the new host’s genetic background and immune system. The quasispecies in the two individuals are related but genetically distinct, as shown by experiments involving infected chimps, vertical transmission, and transplant recipients (Kudo et al., 1997; Murakami et al., 2000; Ni et al., 1997; Power et al., 1995; Prince et al., 2004; Wyatt et al., 1998). Sequencing is also useful in demonstrating replication and tropism of the virus for particular host compartments (Fishman et al., 2008).

Although nucleotide sequencing provides very detailed information about the individual members of the quasispecies, this method is subject to some notable artifacts. Sequence errors may be introduced by the reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase during amplification of the template. DNA polymerases with proofreading activity should always be used when performing PCR for quasispecies analysis to minimize such errors. Studies of quasispecies complexity can be skewed by template re-sampling during PCR when the input nucleic acid concentration is low. When this occurs, the apparent complexity is lower than the true value. In addition, the major variants of the population may be obscured by the repeated copying of minor variants. Given the error rate of the viral polymerase, and the length of the fragment of interest, one can estimate the number of species to expect based on the initial viral RNA concentration (Airaksinen et al., 2003). Significant deviations from this value should be viewed cautiously. In practice, if a 1:100 dilution of the viral RNA is sufficient to generate an RT-PCR product, then template re-sampling is unlikely to occur (Domingo et al., 2006).

Analyzing quasispecies sequences with bioinformatics

Once the sequences of the variants are obtained, a number of bioinformatics based analyses can be performed. The proportion of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in the sequences is often examined. Synonymous or silent mutations (those that do not change the amino acid sequence of the protein) are traditionally considered evolutionarily neutral. Due to the degeneracy of the genetic code, synonymous substitutions can be made for all amino acids except methionine and tryptophan, which each have only one codon. Nonsynonymous substitutions change the amino acid sequence of the protein. The ratio of nonsynonymous substitutions per eligible site (dn) to synonymous substitutions per eligible sites (ds) is an indicator of the strength of the positive or negative selection acting on the population. A dn/ds ratio greater than one is in indicative of “positive selection” acting on the population (Kimura, 1977). Positive selection results in the increased frequency of a nonsynonymous mutation in the population due to the reproductive advantage it confers. Conversely, a ratio of less than one indicates “negative selection,” specifically that nonsynonymous mutations are unfit and have been culled.

Although dn/ds ratios are frequently reported for quasispecies populations, the validity of these ratios as an indicator selective pressure is controversial in these groups. The use of dn/ds ratios as an indicator of selective pressures rests on the assumption that nonsynonymous changes are fixed in the sequence. However, when comparing closely related sequences of the same rapidly evolving species, the majority of observed nonsynonymous substitutions are transient (Rocha et al., 2006). Studies have shown that the relationship between dn/ds ratios and the type of selective pressure acting on the population is dependent on the divergence of sequences within the sample. Sequence samples drawn from different lineages will have dn/ds ratios that accurately reflect the nature of the selective pressure acting on the population. However, dn/ds ratios calculated from sequence samples drawn from a single population (for example, a quasispecies) are not an indicator of the type of selection (Kryazhimskiy and Plotkin, 2008). Since quasispecies are inherently dynamic, selection pressures as reflected by dn/ds ratios can be skewed by a delay in the removal of variants with mutations that reduce viral fitness. In addition, sites in the genome may be subjected to pressures acting on RNA structures embedded in coding regions and/or on overlapping coding sequences that lead to altered dn/ds ratios (Domingo, 2003; Xing and Lee, 2006).

Other parameters commonly of interest when studying the quasispecies composition are the complexity and diversity of the population. Complexity refers to the number of different sequences present in the population. Usually complexity is presented as either the ratio of unique variants to the total number of clones analyzed or as the Shannon entropy:

where n is the number of different species identified, fi is the observed frequency of the particular variant in the quasispecies, and N is the total number of clones sequenced. Dividing by N normalizes for differences in the number of clones analyzed. Statistical comparisons of complexity between two groups are usually made using the Wilcoxon rank sum test or other non parametric tests of the median. A broad spectrum of variants (high complexity) may indicate similar fitness among viral variants and a long duration of stability of the population. Similarly, low complexity may reflect larger differences in fitness and a more recent change in the environment. Alternatively, low complexity may reflect a lack of selection pressures.

The diversity of a quasispecies refers to the relatedness of individuals within the population. The most basic measure of diversity is the average hamming distance, that is, the number of mutated positions in a particular sequence relative to a dominant sequence, consensus sequence, or other reference. More often, diversity is measured using a genetic distance algorithm such as the Jukes-Cantor or Kimura-2-parameter metric, that consider additional factors such as the probabilities of transitions (purine to purine or pyrimidine to pyrimidine substitutions), transversions (pyrimidine to purine and vice versa substitutions), and the global nucleotide or amino acid composition of the sequences. Genetic distances within and between quasispecies are often used to generate multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees. Sequences that cluster or are assigned to the same clades are most closely related to each other. The strength of the clustering of sequences on a phylogenetic tree can be evaluated by repeatedly randomizing the sequences and recreating the tree (bootstrapping).

Transmission and outbreak studies often measure genetic diversity and create phylogenetic trees of the quasispecies of different patients. Usually patients are infected with a single quasispecies that is recognizable as a unique clade on a phylogenetic tree when compared with sequences from other individuals. Infection of multiple people with a single isolate typically leads to divergence in the new hosts. Multiple, closely-related quasispecies evolve from the original quasispecies (Ray et al., 2005). As a result of super-infection, genetically distinct quasispecies can circulate in an individual patient.

Many studies relate intra-patient quasispecies diversity to other clinical features of infection such as progression of disease and response to treatment. Since there is no one standard way to measure diversity, it is difficult to compare results between these studies. In addition, the observed diversity of the quasispecies is partially dependent on the region of the genome analyzed because the conservation of viral genomes is non-uniform.

Single stranded conformation polymorphism (SSCP)

While nucleotide sequencing provides valuable information on the composition of the individual variants, a popular, rapid alternative is SSCP. Denatured single stranded PCR products are separated on a non-denaturing gel at constant temperature by electrophoresis to resolve different variants based on the secondary structure of the nucleic acid (Hayashi, 1991; Hongyo et al., 1993; Orita et al., 1989). It was originally though that variants differing by as little as one base may adopt different secondary structures, and therefore have measurable differences in gel mobility (Melcher, 2000), although more recent studies have found that single nucleotide changes may not resolve as different bands (Vera-Otarola et al., 2009). The gel bands are visualized either by a radiolabel on the control sequence, Southern hybridization, or staining. The number of bands in the lane reflects the number of variants in the sample. This method can detect only those variants that comprise approximately 3% or more of the population (Laskus et al., 1996). Extremely minor variants are unlikely to be detected.

Many variables can affect the performance of SSCP (reviewed in (Hayashi and Yandell, 1993)). For example, the mobility of DNA is affected by the temperature and consistency of the polyacrylamide gel. Reproducible results require electrophoresis to be performed at the same temperature every time. Long fragments may not resolve as clearly as shorter fragments, the optimal range being between 150 and 300 base pairs, although the addition of glycerol can add resolution when larger fragments are used (Kukita et al., 1997). Other factors affecting the sensitivity of SSCP include the concentration of the DNA fragments, the G/C content of the nucleic acids, and properties of the buffer solution.

While SSCP can be a convenient, inexpensive tool for assessing the general composition of the quasispecies, there are important drawbacks. Information on the complexity of the population is obtained by inspection of the gel, but more detailed knowledge of the diversity and specific information on the nature of mutations present in the quasispecies requires the excision and sequencing of the individual bands on the gel, which is both labor intensive and expensive. In addition, because the isolation of individual variants by SSCP is sensitive to a variety of parameters, experimental conditions must be optimized empirically.

Heteroduplex gel shift assays

Heteroduplex gel shift assays are similar in concept to SSCP. This method has been applied to HIV (Delwart et al., 2003) and HCV quasispecies (Wilson et al., 1995). The advantages and drawbacks of heteroduplex gel shift assays are similar to SSCP methods in that the entire population can be readily sampled, but there is no information about the specific substitutions in the population.

There are two types of heteroduplex shift assays: The homo duplex tracking assay (HTA) and clonal frequency analysis (CFA). In both cases, the viral RNA is first isolated and amplified, and a radio-labeled probe is synthesized to hybridize to the region of interest. In the HTA assay, the labeled probe is hybridized to the mixed population of variants present in the PCR amplicon. The heteroduplex products are resolved by electrophoresis under partially denaturing conditions. The different variants in the heterogeneous amplicon will have varied migration due to mismatches with the probe resulting in bubbles that hinder gel mobility and create distinct bands. The number of distinct bands in the lane reflects the number of variants in the quasispecies. In the CFA assay, the variants are separated by cloning into plasmids (as is done for quasispecies sequencing). A number of clones are individually hybridized to the probe. The resulting duplexes are resolved in neighboring lanes using gel electrophoresis. Genetic distance can be calculated by measuring the heteroduplex mobility ratio (HMR): the distance in millimeters from the origin of the gel to a specific heteroduplex divided by the distance in millimeters from the origin to the homoduplex control (the band with the farthest migration). The HMR is calculated for each variant and then averaged to give a measure of genetic diversity for the population. The reduced migration of a mismatched heteroduplex relative to a homoduplex, and the resulting HMR value, is proportional to the number of different nucleotides between two variants (Delwart et al., 1993; Polyak et al., 1997; Wilson et al., 1995). HMR values for two populations can be compared statistically by t-tests (Polyak et al., 1998). The ability to estimate the population diversity is an advantage of heteroduplex gel shift assays over SSCP. However, these assays require variants of a uniform length to differ in sequence by about 1.5% for accurate resolution (Delwart and Gordon, 1997).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF)

In this assay, the extracted RNA templates are reverse transcribed and amplified by RT-PCR, and subsequently used to synthesize tagged peptides. The peptides are subjected to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to identify the amino acid composition of the peptides. This method of analysis is inexpensive and rapid relative to sequencing multiple cloned fragments (Farci et al., 2000; Farci et al., 2002; Yea et al., 2007). An advantage of the MALDI-TOF method of quasispecies analysis over other rapid methods such as SSCP and heteroduplex gel shift assays is the knowledge of the amino acid composition of the fragments, from which information can be deduced about nonsynonymous nucleotide mutations. However, variants comprising less than 5% of the population are not identified.

Biological implications of a quasispecies distribution for RNA viruses

Viruses that circulate as a quasispecies present a unique set of challenges to the host. Variants may differ in their biological properties such as virulence, ability to escape the immune system, resistance to antiviral therapies, and tissue tropism. A specific variant within the quasispecies can have a phenotype that differs from the majority of the population. If such variants arise de novo they can change the course of disease (Duarte et al., 1994). For example, in measles virus infection, certain variants contribute to high virulence, central nervous system tropism, and distinct disease manifestations (Steinhauer and Holland, 1987a). In lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, a single amino acid change can alter the tissue tropism (Dockter et al., 1996). The quasispecies nature of viruses such as HCV and HIV may contribute to the challenge of vaccine development because the use of live attenuated viruses in vaccines is risky due to the potential of these viruses to mutate rapidly and become virulent.

The major implications of a quasispecies distribution are discussed below with examples from studies of HCV.

Transmission and quasispecies divergence

For viruses that circulate as a quasispecies, there are usually multiple variants present at the time of transmission of infection. Transmission of all variants within a quasispecies is not uniform (Gao et al., 2002; Sugitani and Shikata, 1998; Weiner et al., 1993). Often transmission results in a population bottleneck, with only a small fraction of the variants in the original quasispecies passing to the new host. The dominant variants in the inoculum are often poorly adapted to the new environment. As a result, a minor variant in the quasispecies often becomes dominant in the new host. When multiple variants successfully make the transition into the new host, there is high quasispecies diversity during the early phase of infection (Herring et al., 2005).

Within an infected individual HCV quasispecies diversity can vary greatly. Herring et al., reported sequences differing by 1 to 7.8% at the nucleotide level in HVR1 in the quasispecies of 12 subjects during the early phase of infection. A study of an outbreak in which patients were infected from a single source showed that variants present in the inoculum may give rise to divergent populations within an individual patient. The two populations can be as different from each other as they are from the progeny sequences in other patients (Ray et al., 2005). However, the generation of two distinct populations from a single infection event within an individual patient is uncommon.

Compartmentalization

Analysws of variants isolated from different body compartments show that the members of the quasispecies are not randomly distributed. Variants with different tissue tropisms and compartmentalization of genomes have been observed for a number of RNA viruses including HIV and HCV. Sequence variants that are restricted to a particular body compartment have been found in the serum (Cabot et al., 2000; Jang et al., 1999; Shimizu et al., 1997), peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Ducoulombier et al., 2004; Laskus et al., 1998; Navas et al., 1998; Roque-Afonso et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 1997), CNS (Fishman et al., 2008; Forton et al., 2004; Radkowski et al., 2002; Vargas et al., 2002), and other extrahepatic sites in specimens from patients with HCV, suggesting that some portions of the quasispecies may replicate in isolation from other portions. Individuals infected with multiple distinct quasispecies may show complete segregation of the two populations. In extreme cases, sequences of one HCV genotype are isolated from a specific compartment (e.g., liver) and sequences of a different genotype are isolated from a different compartment (e.g., PBMCs). We previously described a patient infected with both genotype 1a and genotype 1b HCV. Genotype 1b variants were found exclusively in the liver, while genotype 1a variants were found in the liver, plasma, and brain tissue (Fishman et al., 2008).

Tissue-specific mutations often occur in the HCV IRES, presumably because the cellular proteins that facilitate IRES function differ between cell types, driving the evolution of variants adapted for the local set of proteins. Investigations have shown that IRES mutations alter translation efficiency (Forton et al., 2004; Gallegos-Orozco et al., 2006). It has been suggested that inefficient variants evolve as a means of down-regulating viral protein expression, thereby evading the immune system (Gallegos-Orozco et al., 2006; Laporte et al., 2000; Laporte et al., 2003); however, it is also possible that IRES mutations promote efficient translation in a specific cell type that was not included in the assay.

The demonstration of sequence compartmentalization of a single quasispecies is usually shown by construction of a phylogenetic tree where variants from a given compartment cluster together, although complete segregation of variants by compartment in separate clades is rare. It is also possible to demonstrate that the genetic distances observed between variants isolated from different compartments are significantly greater than the genetic distances observed between variants in the same compartment using Mantel’s test (see methods of (Roque Afonso et al., 1999)). This method has been applied to compartmentalization studies in both HCV (Roque Afonso et al., 1999) and HIV (Poss et al., 1998).

Viral persistence and progression of disease

A few RNA viruses, including HCV, can establish a chronic infection. It is thought that changes in antigen epitopes may contribute to persistence by allowing the virus to escape from the adaptive immune system. According to this hypothesis, in the absence of immune pressure, there should be little or no antigenic diversity in the viral population. Indeed, one small study of HCV patients with agammaglobulinemia, found limited quasispecies diversity (Kumar et al., 1994). More recent studies of HCV patients undergoing liver transplantation for HCV-related cirrhosis showed that post transplant viral complexity and diversity was lower in HVR1 than pre-transplant, suggesting that immunosuppression can decrease the introduction of new variants into the quasispecies (Feliu et al., 2004; Moreno et al., 2003; Schvoerer et al., 2007). Furthermore, in patients co-infected with HIV, immunosuppression is associated with reduced quasispecies diversity (Canobio et al., 2004; Toyoda et al., 1997).

However, the diversification of quasispecies due to immune pressure remains controversial, and may not be true of all viruses that circulate as a quasispecies. Studies with foot-and-mouth-disease virus and influenza virus show that antigenic diversity and fluctuation can occur even in the absence of immune pressure (Borrego et al., 1993; Domingo et al., 1993; Umetsu et al., 1992). It is likely that the presence of variants whose proteins are not recognized by the immune system contributes to persistence of the virus.

It remains unclear if the increasing complexity and diversity of the quasispecies, and in particular immune escape mutants are the cause or result of chronic infection. Studies of HCV show that progression from acute to chronic infection is associated with an increase in complexity in HVR1 sequences of the quasispecies (Farci et al., 2000). In patients with transfusion acquired HCV, viral clearance was associated with stasis of the quasispecies during acute phase, while progression to chronic infection was associated with evolution of the quasispecies (Farci et al., 2000). In serum samples taken before seroconversion, there was a significant decrease in the diversity of the quasispecies relative to pre-seroconversion serum samples in patients who cleared the virus spontaneously. No such decrease in quasispecies diversity was observed in those who progressed to develop chronic infection. These changes in the quasispecies were observed only in the HVR1 region, underscoring the importance of HVR1 in HCV-host interactions. This study also illustrates how the choice of the region under investigation can impact the results of quasispecies analysis. Furthermore, GB virus B, a distant relative of HCV, has limited quasispecies diversity during acute infection, and rarely progresses to chronic infection and persistence (McGarvey et al., 2008).

During chronic HCV infection, many factors affect the rate of liver disease progression. Advanced disease is associated with a longer duration of infection, male sex, older age at time of infection, HIV and/or hepatitis B virus co-infection, and high consumption of alcohol (Domingo and Gomez, 2007). Interestingly, the disease progression rate is independent of viral load in the circulation and viral genotype. Studies of the relationship between the diversity/complexity of the quasispecies and liver damage, progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and extrahepatic manifestations have yielded conflicting results (Arenas et al., 2004; Canobio et al., 2004; Gonzalez-Peralta et al., 1996; Hayashi et al., 1997; Honda et al., 1994; Koizumi et al., 1995; Lopez-Labrador et al., 1999; Naito et al., 1995; Qin et al., 2005; Sookoian et al., 2000; Vallet et al., 2007; Yuki et al., 1997). High levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are indicative of liver injury. Rothman et al. reported an association between increased complexity of the HCV quasispecies in HVR1 and ALT levels (Rothman et al., 2005). In a study of children, Farci and colleagues found no association between the diversity and complexity of HVR1 sequences and ALT levels before seroconversion, but found that high levels of ALT after conversion correlated with a decrease in complexity and diversity of the quasispecies relative to the pre-seroconversion measurements (Farci et al., 2006). Over time, children with low ALT values had changing populations of virus, with sequential shifts in the populations, while children with high ALT values did not have temporally segregated populations of virus.

Drug and IFN response

The standard therapy for HCV infection consists of weekly injections of pegylated IFN alpha and daily doses of ribavirin for 6 months or a year. The duration depends on the genotype. This regimen leads to a sustained virological response in approximately 42% of patients infected with genotype 1 and 82% of patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3 (Fried et al., 2002; Hadziyannis and Koskinas, 2004; Manns et al., 2001; Pawlotsky, 2003). Many studies have sought to predict the outcome of IFN treatment based on pre-treatment sequence features including specific viral mutations and quasispecies parameters (diversity and complexity). The presence of a quasispecies may contribute to the low success rate of treatment since individual variants may have different levels of natural IFN induction (Pellerin et al., 2004).

Young patients with little or no liver damage, low viral load, non-genotype 1, and a short duration of infection are most likely to achieve a sustained virological response with pegylated IFN alpha/ribavirin treatment (Domingo and Gomez, 2007). Many recent studies associate pre-treatment high complexity and diversity of the HCV quasispecies in HVR1 in chronic infection (Chambers et al., 2005; Kumar et al., 2008; Moreau et al., 2008; Puig-Basagoiti et al., 2001; Sarrazin et al., 2000; Thelu et al., 2001; Ueda et al., 2004) with treatment failure. A decrease in quasispecies complexity over the initial treatment period is associated with sustained virological response (Farci et al., 2002; Salmeron et al., 2008), while conversely no change in the composition of the population is associated with treatment failure (Pawlotsky et al., 1998b; Pawlotsky et al., 1999; Quesnel-Vallieres et al., 2008). Interestingly, some analyses of quasispecies in the NS5A region associate high complexity and diversity with interferon sensitivity (Enomoto et al., 1995; Pawlotsky et al., 1998a; Puig-Basagoiti et al., 2001; Puig-Basagoiti et al., 2005; Saiz et al., 1998; Sarrazin et al., 2002; Ueda et al., 2004; Veillon et al., 2007), however this finding has not been universal (Puig-Basagoiti et al., 2005).

Induction of error catastrophe as an antiviral strategy

In viruses that circulate as a quasispecies, the polymerase error rate is such that on average one point mutation is made per replication cycle (Drake and Holland, 1999). This mutation rate works to the advantage of the virus. Among mammalian viruses, the error rate contributes to fitness by helping the virus evade the immune system (Kamp and Bornholdt, 2002). The beneficial effects of the viral error rate have been demonstrated in a study of poliovirus (Vignuzzi et al., 2006). When the fidelity of the polio polymerase was increased, leading to the generation of fewer variants, the virus showed reduced pathogenicity and neurotropism. The addition of mutagens to the culture media restored fitness (Vignuzzi et al., 2006).

Although RNA viruses incorporate new mutations at extremely high rates, there is a limit to their capacity to absorb mutations. When this capacity is exceeded, the integrity of the genome is compromised, and the virus is eliminated through a process known as error catastrophe. The fact that viral RNA replicases operate at an error level near the threshold for error catastrophe suggests that pharmaceuticals that increase the error rate would be potentially useful anti-viral agents. Holland et al., first applied this concept to the poliovirus by demonstrating a negative effect on replication with the addition of mutagens (Holland et al., 1990). Mutagens have since been used to treat infection with HCV, HIV, and many other RNA viruses (reviewed in (Anderson et al., 2004; Domingo et al., 2005)). A number of hurdles remain in the development of antiviral therapies based on enhanced mutagenesis. The compounds are often toxic and impact cellular enzymes as well as viral polymerases causing mutation of the host genome. In addition, the concentration of the mutagenic agent must be maintained at the optimal level, as suboptimal levels would lead to the selection of resistance mutations or the appearance of variants with new biological properties (Domingo, 2003).

Implications to New Antiviral Strategy

Unfortunately, the standard of care therapy for HCV is expensive, arduous, fraught with side effects, and ineffective in about 50% of patients with genotype 1 HCV. Recent efforts to improve treatments for HCV have centered on the development of therapies to inhibit specific steps in the HCV life cycle. Over 30 agents that inhibit viral entry, proteolytic cleavage, RNA replication, and assembly are in the pipeline (reviewed in (Thompson and McHutchison, 2009)). However, due to the quasispecies nature of HCV, it will be difficult to develop durable small molecule inhibitors of HCV. Variants harboring resistant mutations to protease inhibitors have been observed in treatment naïve subjects (Bartels et al., 2008; Sarrazin et al., 2007). The emergence of minor variants with drug resistant phenotypes can be anticipated and has been observed in early trials of the STAT-C (specifically targeted anti-viral therapy for HCV) drugs. Although resistance mutations have generally been associated with reduced viral fitness relative to the wild-type (He et al., 2008), these variants can become major species during treatment. As a consequence, resistant mutants are likely to become more prevalent in the population, reducing the success rate of newly developed drugs. Combination therapy of protease inhibitors with interferon and ribavirin should increase the likelihood of achieving a sustained virological response.

Conclusions

The quasispecies nature of RNA viruses, and HCV in particular, has significant implications for the behaviors of these viruses in vivo. The exact mechanisms by which the variants in the population contribute to compartmentalization, viral persistence and progression, and transmission events remain open questions.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IFN

interferon

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- HVR1

first hypervariable region

- SSCP

single stranded conformation polymorphism

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus-1

- HTA

homo duplex tracking assay

- CFA

clonal frequency analysis

- HMR

heteroduplex mobility ratio

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Airaksinen A, Pariente N, Menendez-Arias L, Domingo E. Curing of foot-and-mouth disease virus from persistently infected cells by ribavirin involves enhanced mutagenesis. Virology. 2003;311:339–349. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JP, Daifuku R, Loeb LA. Viral error catastrophe by mutagenic nucleosides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2004;58:183–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas JI, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Laskus T, Wilkinson J, Khatib A, Fasola C, Adair D, Radkowski M, Kibler KV, Nowicki M, Douglas D, Williams J, Netto G, Mulligan D, Klintmalm G, Rakela J, Vargas HE. Hepatitis C virus quasi-species dynamics predict progression of fibrosis after liver transplantation. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2037–2046. doi: 10.1086/386338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels DJ, Zhou Y, Zhang EZ, Marcial M, Byrn RA, Pfeiffer T, Tigges AM, Adiwijaya BS, Lin C, Kwong AD, Kieffer TL. Natural prevalence of hepatitis C virus variants with decreased sensitivity to NS3.4A protease inhibitors in treatment-naive subjects. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:800–807. doi: 10.1086/591141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biebricher CK, Eigen M. The error threshold. Virus Res. 2005;107:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego B, Novella IS, Giralt E, Andreu D, Domingo E. Distinct repertoire of antigenic variants of foot-and-mouth disease virus in the presence or absence of immune selection. J Virol. 1993;67:6071–6079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6071-6079.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukh J, Miller RH, Purcell RH. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:41–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull JJ, Meyers LA, Lachmann M. Quasispecies made simple. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabot B, Martell M, Esteban JI, Sauleda S, Otero T, Esteban R, Guardia J, Gomez J. Nucleotide and amino acid complexity of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in serum and liver. J Virol. 2000;74:805–811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.805-811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canobio S, Guilbert CM, Troesch M, Samson J, Lemay M, Pelletier VA, Bernard-Bonnin AC, Kozielski R, Lapointe N, Martin SR, Soudeyns H. Differing patterns of liver disease progression and hepatitis C virus (HCV) quasispecies evolution in children vertically coinfected with HCV and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4365–4369. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.9.4365-4369.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers TJ, Fan X, Droll DA, Hembrador E, Slater T, Nickells MW, Dustin LB, Dibisceglie AM. Quasispecies heterogeneity within the E1/E2 region as a pretreatment variable during pegylated interferon therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:3071–3083. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.3071-3083.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo QL, Richman KH, Han JH, Berger K, Lee C, Dong C, Gallegos C, Coit D, Medina-Selby R, Barr PJ. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2451–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas I, Moya A, Gonzalez-Candelas F. Validating viral quasispecies with digital organisms: a re-examination of the critical mutation rate. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre JC, Holland JJ. RNA virus quasispecies populations can suppress vastly superior mutant progeny. J Virol. 1990;64:6278–6281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6278-6281.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwart EL, Gordon CJ. Tracking changes in HIV-1 envelope quasispecies using DNA heteroduplex analysis. Methods. 1997;12:348–354. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwart EL, Orton S, Parekh B, Dobbs T, Clark K, Busch MP. Two percent of HIV-positive U.S. blood donors are infected with non-subtype B strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:1065–1070. doi: 10.1089/088922203771881149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwart EL, Shpaer EG, Louwagie J, McCutchan FE, Grez M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins JI. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockter J, Evans CF, Tishon A, Oldstone MB. Competitive selection in vivo by a cell for one variant over another: implications for RNA virus quasispecies in vivo. J Virol. 1996;70:1799–1803. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1799-1803.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E. Quasispecies and the development of new antiviral strategies. Prog Drug Res. 2003;60:133–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8012-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Diez J, Martinez MA, Hernandez J, Holguin A, Borrego B, Mateu MG. New observations on antigenic diversification of RNA viruses. Antigenic variation is not dependent on immune selection. J Gen Virol. 1993;74 (Pt 10):2039–2045. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-10-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Escarmis C, Lazaro E, Manrubia SC. Quasispecies dynamics and RNA virus extinction. Virus Res. 2005;107:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Escarmis C, Martinez MA, Martinez-Salas E, Mateu MG. Foot-and-mouth disease virus populations are quasispecies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:33–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77011-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Gomez J. Quasispecies and its impact on viral hepatitis. Virus Res. 2007;127:131–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Martin V, Perales C, Grande-Perez A, Garcia-Arriaza J, Arias A. Viruses as quasispecies: biological implications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;299:51–82. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26397-7_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Martinez-Salas E, Sobrino F, de la Torre JC, Portela A, Ortin J, Lopez-Galindez C, Perez-Brena P, Villanueva N, Najera R. The quasispecies (extremely heterogeneous) nature of viral RNA genome populations: biological relevance--a review. Gene. 1985;40:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo E, Sabo D, Taniguchi T, Weissmann C. Nucleotide sequence heterogeneity of an RNA phage population. Cell. 1978;13:735–744. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake JW, Holland JJ. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13910–13913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte EA, Novella IS, Weaver SC, Domingo E, Wain-Hobson S, Clarke DK, Moya A, Elena SF, de la Torre JC, Holland JJ. RNA virus quasispecies: significance for viral disease and epidemiology. Infect Agents Dis. 1994;3:201–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducoulombier D, Roque-Afonso AM, Di Liberto G, Penin F, Kara R, Richard Y, Dussaix E, Feray C. Frequent compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus variants in circulating B cells and monocytes. Hepatology. 2004;39:817–825. doi: 10.1002/hep.20087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. New concepts for dealing with the evolution of nucleic acids. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:307–320. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. Viral quasispecies. Sci Am. 1993;269:42–49. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0793-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. On the nature of virus quasispecies. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:216–218. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)20011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M. Natural selection: a phase transition? Biophys Chem. 2000;85:101–123. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigen M, Schuster P. The hypercycle. A principle of natural self organization. 1979 doi: 10.1007/BF00450633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto N, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Yamamoto C, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. Comparison of full-length sequences of interferon-sensitive and resistant hepatitis C virus 1b. Sensitivity to interferon is conferred by amino acid substitutions in the NS5A region. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:224–230. doi: 10.1172/JCI118025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson N, Pachter L, Mitsuya Y, Rhee SY, Wang C, Gharizadeh B, Ronaghi M, Shafer RW, Beerenwinkel N. Viral population estimation using pyrosequencing. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farci P, Quinti I, Farci S, Alter HJ, Strazzera R, Palomba E, Coiana A, Cao D, Casadei AM, Ledda R, Iorio R, Vegnente A, Diaz G, Tovo PA. Evolution of hepatitis C viral quasispecies and hepatic injury in perinatally infected children followed prospectively. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8475–8480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602546103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farci P, Shimoda A, Coiana A, Diaz G, Peddis G, Melpolder JC, Strazzera A, Chien DY, Munoz SJ, Balestrieri A, Purcell RH, Alter HJ. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science. 2000;288:339–344. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farci P, Strazzera R, Alter HJ, Farci S, Degioannis D, Coiana A, Peddis G, Usai F, Serra G, Chessa L, Diaz G, Balestrieri A, Purcell RH. Early changes in hepatitis C viral quasispecies during interferon therapy predict the therapeutic outcome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3081–3086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052712599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliu A, Gay E, Garcia-Retortillo M, Saiz JC, Forns X. Evolution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies immediately following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1131–1139. doi: 10.1002/lt.20206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman SL, Murray JM, Eng FJ, Walewski JL, Morgello S, Branch AD. Molecular and bioinformatic evidence of hepatitis C virus evolution in brain. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:597–607. doi: 10.1086/526519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forns X, Purcell RH, Bukh J. Quasispecies in viral persistence and pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:402–410. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forton DM, Karayiannis P, Mahmud N, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thomas HC. Identification of unique hepatitis C virus quasispecies in the central nervous system and comparative analysis of internal translational efficiency of brain, liver, and serum variants. J Virol. 2004;78:5170–5183. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5170-5183.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr, Haussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D, Craxi A, Lin A, Hoffman J, Yu J. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos-Orozco JF, Arenas JI, Vargas HE, Kibler KV, Wilkinson JK, Nowicki M, Radkowski M, Nasseri J, Rakela J, Laskus T. Selection of different 5′ untranslated region hepatitis C virus variants during post-transfusion and post-transplantation infection. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:489–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Buskell Z, Seeff L, Tabor E. Drift in the hypervariable region of the hepatitis C virus during 27 years in two patients. J Med Virol. 2002;68:60–67. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez JC, Cacho I. Can Nietzsche power relationships be experimentally approached with theoretical and viral quasispecies? Contributions to Science (Revista del Institut d’Estudis Catalans) 2001;2:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Qian K, She JY, Davis GL, Ohno T, Mizokami M, Lau JY. Clinical implications of viral quasispecies heterogeneity in chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1996;49:242–247. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199607)49:3<242::AID-JMV14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gretch DR, Polyak SJ. The quasisepcies nature of Hepatitis C Virus: research methods and biological implications. 1997:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gretch DR, Polyak SJ, Wilson JJ, Carithers RL, Jr, Perkins JD, Corey L. Tracking hepatitis C virus quasispecies major and minor variants in symptomatic and asymptomatic liver transplant recipients. J Virol. 1996;70:7622–7631. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7622-7631.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadziyannis SJ, Koskinas JS. Differences in epidemiology, liver disease and treatment response among HCV genotypes. Hepatol Res. 2004;29:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi J, Kishihara Y, Yamaji K, Furusyo N, Yamamoto T, Pae Y, Etoh Y, Ikematsu H, Kashiwagi S. Hepatitis C viral quasispecies and liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 1997;25:697–701. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K. PCR-SSCP: a simple and sensitive method for detection of mutations in the genomic DNA. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:34–38. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Yandell DW. How sensitive is PCR-SSCP? Hum Mutat. 1993;2:338–346. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, King MS, Kempf DJ, Lu L, Lim HB, Krishnan P, Kati W, Middleton T, Molla A. Relative replication capacity and selective advantage profiles of protease inhibitor-resistant hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3 protease mutants in the HCV genotype 1b replicon system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1101–1110. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01149-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring BL, Tsui R, Peddada L, Busch M, Delwart EL. Wide range of quasispecies diversity during primary hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:4340–4346. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4340-4346.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Minkah N, Leipzig J, Wang G, Arens MQ, Tebas P, Bushman FD. DNA bar coding and pyrosequencing to identify rare HIV drug resistance mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JJ, de la Torre JC, Steinhauer DA. RNA virus populations as quasispecies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;176:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77011-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JJ, Domingo E, de la Torre JC, Steinhauer DA. Mutation frequencies at defined single codon sites in vesicular stomatitis virus and poliovirus can be increased only slightly by chemical mutagenesis. J Virol. 1990;64:3960–3962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3960-3962.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EC. Error thresholds and the constraints to RNA virus evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:543–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EC, Moya A. Is the quasispecies concept relevant to RNA viruses? J Virol. 2002;76:460–465. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.1.460-462.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Kaneko S, Sakai A, Unoura M, Murakami S, Kobayashi K. Degree of diversity of hepatitis C virus quasispecies and progression of liver disease. Hepatology. 1994;20:1144–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongyo T, Buzard GS, Calvert RJ, Weghorst CM. ‘Cold SSCP’: a simple, rapid and non-radioactive method for optimized single-strand conformation polymorphism analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3637–3642. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SJ, Wang LF, Radkowski M, Rakela J, Laskus T. Differences between hepatitis C virus 5′ untranslated region quasispecies in serum and liver. J Gen Virol. 1999;80 (Pt 3):711–716. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GM, Worobey M, Woelk CH, Holmes EC. Evidence for the non-quasispecies evolution of RNA viruses [corrected] Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:987–994. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamp C, Bornholdt S. Coevolution of quasispecies: B-cell mutation rates maximize viral error catastrophes. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:068104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.068104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. Preponderance of synonymous changes as evidence for the neutral theory of molecular evolution. Nature. 1977;267:275–276. doi: 10.1038/267275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Rice PA, Friedman JM, Steitz TA. The structure of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. 2009:223–249. doi: 10.1126/science.1377403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi K, Enomoto N, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. Diversity of quasispecies in various disease stages of chronic hepatitis C virus infection and its significance in interferon treatment. Hepatology. 1995;22:30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryazhimskiy S, Plotkin JB. The population genetics of dN/dS. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo T, Yanase Y, Ohshiro M, Yamamoto M, Morita M, Shibata M, Morishima T. Analysis of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies nature and buoyant densities of maternal virus populations. J Med Virol. 1997;51:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukita Y, Tahira T, Sommer SS, Hayashi K. SSCP analysis of long DNA fragments in low pH gel. Hum Mutat. 1997;10:400–407. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:5<400::AID-HUMU11>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Malik A, Asim M, Chakravarti A, Das RH, Kar P. Response of combination therapy on viral load and disease severity in chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1107–1113. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar U, Monjardino J, Thomas HC. Hypervariable region of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein (E2/NS1) in an agammaglobulinemic patient. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1072–1075. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Bain C, Maurel P, Inchauspe G, Agut H, Cahour A. Differential distribution and internal translation efficiency of hepatitis C virus quasispecies present in dendritic and liver cells. Blood. 2003;101:52–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte J, Malet I, Andrieu T, Thibault V, Toulme JJ, Wychowski C, Pawlotsky JM, Huraux JM, Agut H, Cahour A. Comparative analysis of translation efficiencies of hepatitis C virus 5′ untranslated regions among intraindividual quasispecies present in chronic infection: opposite behaviors depending on cell type. J Virol. 2000;74:10827–10833. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10827-10833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskus T, Radkowski M, Wang LF, Jang SJ, Vargas H, Rakela J. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies in patients infected with HIV-1: correlation with extrahepatic viral replication. Virology. 1998;248:164–171. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskus T, Wang LF, Rakela J, Vargas H, Pinna AD, Tsamandas AC, Demetris AJ, Fung J. Dynamic behavior of hepatitis C virus in chronically infected patients receiving liver graft from infected donors. Virology. 1996;220:171–176. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Labrador FX, Ampurdanes S, Gimenez-Barcons M, Guilera M, Costa J, Jimenez de Anta MT, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rodes J, Saiz JC. Relationship of the genomic complexity of hepatitis C virus with liver disease severity and response to interferon in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection [correction of interferon] Hepatology. 1999;29:897–903. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z, Dewell SB, Du L, Fierro JM, Gomes XV, Godwin BC, He W, Helgesen S, Ho CH, Irzyk GP, Jando SC, Alenquer ML, Jarvie TP, Jirage KB, Kim JB, Knight JR, Lanza JR, Leamon JH, Lefkowitz SM, Lei M, Li J, Lohman KL, Lu H, Makhijani VB, McDade KE, McKenna MP, Myers EW, Nickerson E, Nobile JR, Plant R, Puc BP, Ronan MT, Roth GT, Sarkis GJ, Simons JF, Simpson JW, Srinivasan M, Tartaro KR, Tomasz A, Vogt KA, Volkmer GA, Wang SH, Wang Y, Weiner MP, Yu P, Begley RF, Rothberg JM. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell M, Esteban JI, Quer J, Genesca J, Weiner A, Esteban R, Guardia J, Gomez J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes: quasispecies nature of HCV genome distribution. J Virol. 1992;66:3225–3229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3225-3229.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaughan GW, Laskus T, Vargas HE. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies: misunderstood and mistreated? Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1048–1052. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey MJ, Iqbal M, Nastos T, Karayiannis P. Restricted quasispecies variation following infection with the GB virus B. Virus Res. 2008;135:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher U. The ‘30K’ superfamily of viral movement proteins. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:257–266. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau I, Levis J, Crosbie O, Kenny-Walsh E, Fanning LJ. Correlation between pre-treatment quasispecies complexity and treatment outcome in chronic HCV genotype 3a. Virol J. 2008;5:78. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno GJ, del Campo TS, Moraleda GG, Garcia GM, de Vicente LE, Nuno Vazquez-Garza J, Fortun AJ, Martin P, Barcena MR. Analysis of hepatitis C viral quasispecies in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1838–1840. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00632-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya A, Elena SF, Bracho A, Miralles R, Barrio E. The evolution of RNA viruses: A population genetics view. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6967–6973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami J, Okamoto M, Miyata H, Nagata I, Shiraki K, Hino S. Evolution in the hypervariable region of hepatitis C virus in infants after vertical transmission. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:450–456. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200010000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M, Hayashi N, Moribe T, Hagiwara H, Mita E, Kanazawa Y, Kasahara A, Fusamoto H, Kamada T. Hepatitis C viral quasispecies in hepatitis C virus carriers with normal liver enzymes and patients with type C chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 1995;22:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas S, Martin J, Quiroga JA, Castillo I, Carreno V. Genetic diversity and tissue compartmentalization of the hepatitis C virus genome in blood mononuclear cells, liver, and serum from chronic hepatitis C patients. J Virol. 1998;72:1640–1646. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1640-1646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni YH, Chang MH, Chen PJ, Lin HH, Hsu HY. Evolution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in mothers and infants infected through mother-to-infant transmission. J Hepatol. 1997;26:967–974. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, May RM. Coexistence and competition in HIV infections. J Theor Biol. 1992;159:329–342. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80728-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita M, Suzuki Y, Sekiya T, Hayashi K. Rapid and sensitive detection of point mutations and DNA polymorphisms using the polymerase chain reaction. Genomics. 1989;5:874–879. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky JM. The nature of interferon-alpha resistance in hepatitis C virus infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:587–592. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky JM, Germanidis G, Frainais PO, Bouvier M, Soulier A, Pellerin M, Dhumeaux D. Evolution of the hepatitis C virus second envelope protein hypervariable region in chronically infected patients receiving alpha interferon therapy. J Virol. 1999;73:6490–6499. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6490-6499.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky JM, Germanidis G, Neumann AU, Pellerin M, Frainais PO, Dhumeaux D. Interferon resistance of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: relationship to nonstructural 5A gene quasispecies mutations. J Virol. 1998a;72:2795–2805. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2795-2805.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlotsky JM, Pellerin M, Bouvier M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Germanidis G, Bastie A, Darthuy F, Remire J, Soussy CJ, Dhumeaux D. Genetic complexity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of hepatitis C virus (HCV): influence on the characteristics of the infection and responses to interferon alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1998b;54:256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin M, Lopez-Aguirre Y, Penin F, Dhumeaux D, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies variability modulates nonstructural protein 5A transcriptional activation, pointing to cellular compartmentalization of virus-host interactions. J Virol. 2004;78:4617–4627. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4617-4627.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak SJ, Faulkner G, Carithers RL, Jr, Corey L, Gretch DR. Assessment of hepatitis C virus quasispecies heterogeneity by gel shift analysis: correlation with response to interferon therapy. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1101–1107. doi: 10.1086/516448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak SJ, McArdle S, Liu SL, Sullivan DG, Chung M, Hofgartner WT, Carithers RL, Jr, McMahon BJ, Mullins JI, Corey L, Gretch DR. Evolution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in hypervariable region 1 and the putative interferon sensitivity-determining region during interferon therapy and natural infection. J Virol. 1998;72:4288–4296. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4288-4296.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss M, Rodrigo AG, Gosink JJ, Learn GH, de Vange PD, Martin HL, Jr, Bwayo J, Kreiss JK, Overbaugh J. Evolution of envelope sequences from the genital tract and peripheral blood of women infected with clade A human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:8240–8251. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8240-8251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JP, Lawlor E, Davidson F, Holmes EC, Yap PL, Simmonds P. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of infection with hepatitis C virus in recipients of anti-D immunoglobulin. Lancet. 1995;345:1211–1213. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince AM, Pawlotsky JM, Soulier A, Tobler L, Brotman B, Pfahler W, Lee DH, Li L, Shata MT. Hepatitis C virus replication kinetics in chimpanzees with self-limited and chronic infections. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:236–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Basagoiti F, Forns X, Furcic I, Ampurdanes S, Gimenez-Barcons M, Franco S, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Saiz JC. Dynamics of hepatitis C virus NS5A quasispecies during interferon and ribavirin therapy in responder and non-responder patients with genotype 1b chronic hepatitis C. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1067–1075. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Basagoiti F, Saiz JC, Forns X, Ampurdanes S, Gimenez-Barcons M, Franco S, Sanchez-Fueyo A, Costa J, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rodes J. Influence of the genetic heterogeneity of the ISDR and PePHD regions of hepatitis C virus on the response to interferon therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2001;65:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Shire NJ, Keenan ED, Rouster SD, Eyster ME, Goedert JJ, Koziel MJ, Sherman KE. HCV quasispecies evolution: association with progression to end-stage liver disease in hemophiliacs infected with HCV or HCV/HIV. Blood. 2005;105:533–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel-Vallieres M, Lemay M, Lapointe N, Martin SR, Soudeyns H. HCV quasispecies evolution during treatment with interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in two children coinfected with HCV and HIV-1. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkowski M, Wilkinson J, Nowicki M, Adair D, Vargas H, Ingui C, Rakela J, Laskus T. Search for hepatitis C virus negative-strand RNA sequences and analysis of viral sequences in the central nervous system: evidence of replication. J Virol. 2002;76:600–608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.600-608.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray SC, Fanning L, Wang XH, Netski DM, Kenny-Walsh E, Thomas DL. Divergent and convergent evolution after a common-source outbreak of hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1753–1759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EP, Smith JM, Hurst LD, Holden MT, Cooper JE, Smith NH, Feil EJ. Comparisons of dN/dS are time dependent for closely related bacterial genomes. J Theor Biol. 2006;239:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque Afonso AM, Jiang J, Penin F, Tareau C, Samuel D, Petit MA, Bismuth H, Dussaix E, Feray C. Nonrandom distribution of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell subsets. J Virol. 1999;73:9213–9221. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9213-9221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque-Afonso AM, Ducoulombier D, Di Liberto G, Kara R, Gigou M, Dussaix E, Samuel D, Feray C. Compartmentalization of hepatitis C virus genotypes between plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 2005;79:6349–6357. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6349-6357.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AL, Morishima C, Bonkovsky HL, Polyak SJ, Ray R, Di Bisceglie AM, Lindsay KL, Malet PF, Chang M, Gretch DR, Sullivan DG, Bhan AK, Wright EC, Koziel MJ. Associations among clinical, immunological, and viral quasispecies measurements in advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:617–625. doi: 10.1002/hep.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz JC, Lopez-Labrador FX, Ampurdanes S, Dopazo J, Forns X, Sanchez-Tapias JM, Rodes J. The prognostic relevance of the nonstructural 5A gene interferon sensitivity determining region is different in infections with genotype 1b and 3a isolates of hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:839–847. doi: 10.1086/515243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmeron J, Casado J, Rueda PM, Lafuente V, Diago M, Romero-Gomez M, Palacios A, Leon J, Gila A, Quiles R, Rodriguez L, Ruiz-Extremera A. Quasispecies as predictive factor of rapid, early and sustained virological responses in chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1, treated with peginterferon-ribavirin. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin C, Herrmann E, Bruch K, Zeuzem S. Hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A protein and interferon resistance: a new model for testing the reliability of mutational analyses. J Virol. 2002;76:11079–11090. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11079-11090.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin C, Kieffer TL, Bartels D, Hanzelka B, Muh U, Welker M, Wincheringer D, Zhou Y, Chu HM, Lin C, Weegink C, Reesink H, Zeuzem S, Kwong AD. Dynamic hepatitis C virus genotypic and phenotypic changes in patients treated with the protease inhibitor telaprevir. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1767–1777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin C, Kornetzky I, Ruster B, Lee JH, Kronenberger B, Bruch K, Roth WK, Zeuzem S. Mutations within the E2 and NS5A protein in patients infected with hepatitis C virus type 3a and correlation with treatment response. Hepatology. 2000;31:1360–1370. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.7987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvoerer E, Soulier E, Royer C, Renaudin AC, Thumann C, Fafi-Kremer S, Brignon N, Doridot S, Meyer N, Pinson P, Ellero B, Woehl-Jaegle ML, Meyer C, Wolf P, Zachary P, Baumert T, Stoll-Keller F. Early evolution of hepatitis C virus (HCV) quasispecies after liver transplant for HCV-related disease. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:528–536. doi: 10.1086/519691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu YK, Igarashi H, Kanematu T, Fujiwara K, Wong DC, Purcell RH, Yoshikura H. Sequence analysis of the hepatitis C virus genome recovered from serum, liver, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infected chimpanzees. J Virol. 1997;71:5769–5773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5769-5773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simen BB, Simons JF, Hullsiek KH, Novak RM, Macarthur RD, Baxter JD, Huang C, Lubeski C, Turenchalk GS, Braverman MS, Desany B, Rothberg JM, Egholm M, Kozal MJ. Low-abundance drug-resistant viral variants in chronically HIV-infected, antiretroviral treatment-naive patients significantly impact treatment outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:693–701. doi: 10.1086/596736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds P. Variability of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1995;21:570–583. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sookoian S, Flichman D, Castano G, Frider B, Campos R. Relationship between diversity of hepatitis C quasispecies and histological severity of liver disease. Medicina (B Aires) 2000;60:587–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]