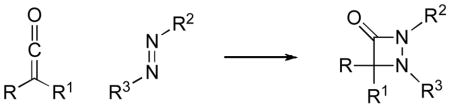

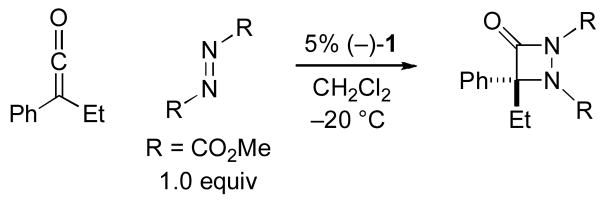

Although aza-β-lactams have attracted interest due to their biological activity[1] and to their utility as intermediates in organic chemistry (e.g., for the generation of α-amino acids[2] and of hydantoins[3]),[4] only limited progress has been described with regard to the enantioselective synthesis of this family of heterocycles.[5] One attractive, convergent approach to the formation of aza-β-lactams is the [2+2] cycloaddition of a ketene with an azo compound [Eq. (1)].[6] To the best of our knowledge, no stereoselective variants of this process have yet been reported.

|

(1) |

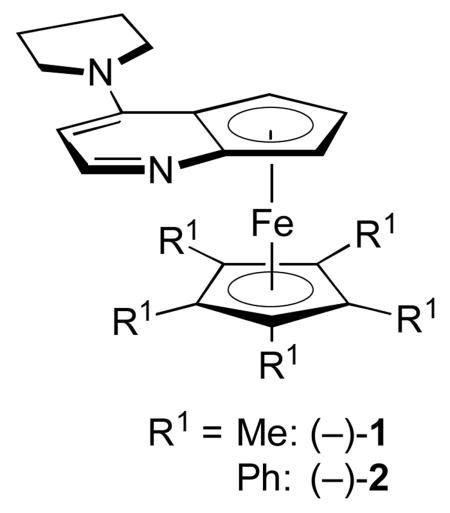

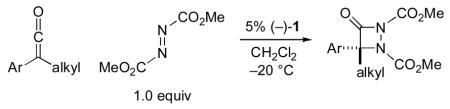

We have been exploring the use of chiral derivatives of PPY (PPY = 4-(pyrrolidino)pyridine; e.g., 1 and 2) as enantioselective catalysts for an array of transformations,[7] including couplings of ketenes with imines[8] and with aldehydes.[9,10] Although there are no reports of nucleophilic catalysis of [2+2] cycloadditions of ketenes with azo compounds, we were intrigued by the possibility that our planar-chiral pyridines might be effective in this role. In this investigation, we establish that PPY derivative 1 can achieve the first catalytic asymmetric synthesis of aza-β-lactams, via [2+2] cycloadditions of ketenes with azo compounds [Eq. (2)].

|

(2) |

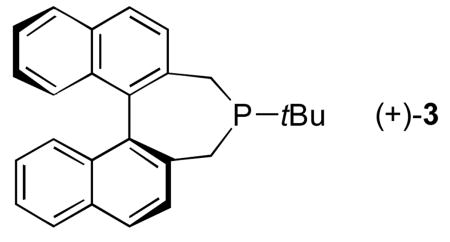

As part of our initial study, we examined the cycloaddition of phenyl ethyl ketene with dimethyl azodicarboxylate (1.0 equiv). We were pleased to determine that planar-chiral PPY derivative 1 serves as an effective catalyst for the desired coupling, generating the aza-β-lactam in good ee and yield (Table 1, entry 1; in the absence of a catalyst, there is no reaction: entry 2). Under the same conditions, a related catalyst (2), as well as a variety of chiral phosphines and cinchona alkaloids, provide poor enantioselectivity or little of the cycloaddition product (e.g., entries 3–5).[11,12] The substituents of the azo compound have a significant impact on the ee and the yield, with the methoxycarbonyl group affording the best results (entry 1 vs. entries 6–9). If ClCH2CH2Cl, rather than CH2Cl2, is employed as the solvent, then formation of the aza-β-lactam proceeds less efficiently (entry 1 vs. entry 10). The reaction temperature of choice appears to be −20 °C (entry 1 vs. entries 11–12).[13]

Table 1.

Nucleophile-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of aza-β-lactams: Effect of reaction parameters.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Change from the “standard” conditions | ee (%) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | none | 86 | 89 |

| 2 | no (−)-1 | – | <5 |

| 3 | (−)-2, instead of (−)-1 | −15 | 65 |

| 4 | (+)-3, instead of (−)-1 | <5 | 65 |

| 5 | quinine, instead of (−)-1 | – | <5 |

| 6 | R = CO2Et | 80 | 85 |

| 7 | R = CO2iPr | 32 | 81 |

| 8 | R = CO2CH2CCl3 | 20 | 20 |

| 9 | R = CO(piperidinyl) | – | <5 |

| 10 | ClCH2CH2Cl, instead of CH2Cl2 | 87 | 65 |

| 11 | −30 °C | 85 | 68 |

| 12 | −10 °C | 73 | 68 |

A negative ee value signifies that the opposite enantiomer of the product is formed preferentially.

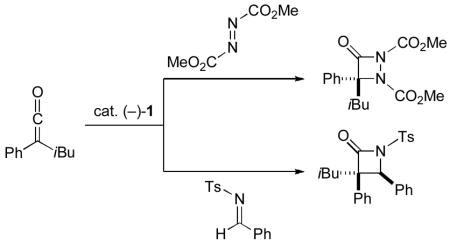

The optimized conditions can be applied to the enantioselective synthesis of aza-β-lactams from a variety of ketenes (Table 2). If the alkyl group is small (Me or primary), the desired heterocycle is generally produced with good, not excellent, enantioselectivity (~85% ee; entries 1–7). Fortunately, the ee of the aza-β-lactams is readily enhanced by recrystallization (e.g., the product generated from phenyl ethyl ketene can be obtained in >99% ee after a single crystallization; see entry 2 of Table 2). In the case of ketenes that bear a secondary alkyl group, catalyst 1 typically furnishes the aza-β-lactam with very good enantioselectivity and yield (>90% ee; entries 8–13).[14]

Table 2.

Nucleophile-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of aza-β-lactams (for the reaction conditions, see [Eq. (2)]).

| entry | Ar | alkyl | ee (%) | yield (%)[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ph | Me | 85 | 53 |

| 2 | Ph | Et | 86 (>99[b]) | 89 |

| 3 | m-tolyl | Et | 85 | 79 |

| 4 | o-tolyl | Et | 67 | 46 |

| 5 | o-anisyl | Et | 93 | 89 |

| 6 | Ph | Bn | 81 | 73 |

| 7 | Ph | iBu | 83 | 87 |

| 8 | Ph | cyclopentyl | 86 | 84 |

| 9 | Ph | cyclohexyl | 94 | 90 |

| 10 | Ph | iPr | 95 | 91 |

| 11 | p-anisyl | iPr | 96 | 91 |

| 12 | p-ClC6H4 | iPr | 92 | 90 |

| 13 | 3-thiophenyl | iPr | 96 | 90 |

All data are the average of two experiments.

Isolated yield.

ee after one crystallization from isopropanol (overall yield: 71%).

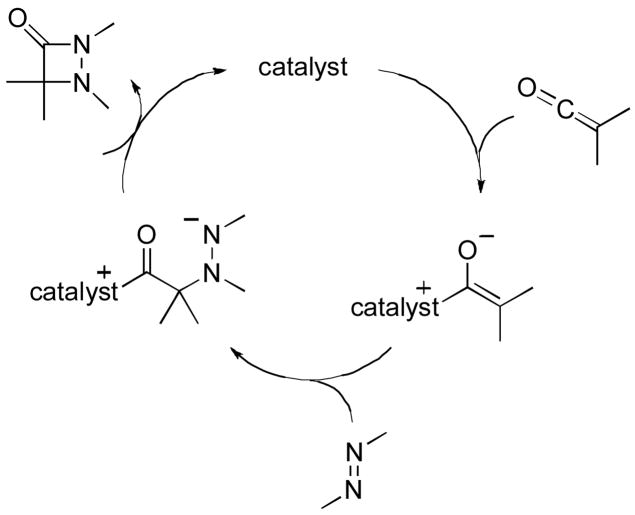

A plausible mechanism for this new nucleophile-catalyzed method for the synthesis of aza-β-lactams is illustrated in Figure 1. Interestingly, the configuration at the quaternary stereocenter is different from that produced in Staudinger reactions that are catalyzed by PPY derivative 1 [Eq. (3)],[8b] which are believed to proceed through a similar pathway.[15]

Figure 1.

Possible mechanism for the nucleophile-catalyzed synthesis of aza-β-lactams.

|

(3) |

In conclusion, we have developed a new process, the nucleophile-catalyzed [2+2] cycloaddition of ketenes with azo compounds to generate aza-β-lactams. In addition, we have established that planar-chiral PPY derivative 1 achieves this convergent transformation with good enantioselectivity, thereby providing the first catalytic asymmetric synthesis of this useful family of heterocycles.

Experimental Section

General procedure: In a glove box, a solution was prepared of the ketene (0.68 mmol) and dimethyl azodicarboxylate (100 mg, 0.68 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (49 mL). A solution was also prepared of catalyst (−)-1 (13 mg, 0.035 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (0.8 mL). Both vessels were removed from the glove box and placed in a −20 °C bath. After 10 minutes, the solution of the catalyst was added by syringe to the solution of ketene and dimethyl azodicarboxylate. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hours at −20 °C, and then the solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography.

Footnotes

We thank Dr. Xing Dai, Dr. Maximilian Dochnahl, and Takashi Nakai for helpful discussions and for experimental assistance. Support has been provided by the NIH (National Institute of General Medical Sciences: R01-GM57034), Merck Research Laboratories, and Novartis.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.For example, see: Morioka H, Takezawa M, Shibai H, Okawara T, Furukawa M. Agric Biol Chem. 1986;50:1757–1764.

- 2.For leading references to the synthesis and utility of enantioenriched α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids, see: Cativiela C, Diaz-de-Villegas MD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:569–623.Vogt H, Bräse S. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:406–430. doi: 10.1039/b611091f.

- 3.For leading references to the synthesis and utility of hydantoins, see: Meusel M, Gütschow M. Org Prep Proced Int. 2004;36:391–443. b) Phenytoin sodium and fosphenytoin, which serve as epilepsy medications, are examples of bioactive hydantoins.

- 4.For examples of methods for the synthesis of aza-β-lactams, see: Hegedus LS, Lundmark BR. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:9194–9198.Taylor EC, Haley NF, Clemens RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7743–7752.Lawton G, Moody CJ, Pearson CJ. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1987:899–902.

- 5.Achiwa K, Yamada S-i. Tetrahedron Lett. 1974;20:1799–1802. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a pioneering study, see: Cook AH, Jones DG. J Chem Soc. 1941:184–187.

- 7.For leading references to early studies, see: Fu GC. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:542–547. doi: 10.1021/ar030051b.For two recent investigations, see: Lee EC, McCauley KM, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:977–979. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604312.Dai X, Nakai T, Romero JAC, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:4367–4369. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700697.

- 8.a) Lee EC, Hodous BL, Bergin E, Shih C, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11586–11587. doi: 10.1021/ja052058p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hodous BL, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1578–1579. doi: 10.1021/ja012427r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JE, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:6358–6360. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For an overview of the chemistry of ketenes, see: Tidwell TT. Ketenes. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2006.

- 11.For previous examples of the use of phosphepine 3 as a chiral nucleophilic catalyst, see: Wurz RP, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12234–12235. doi: 10.1021/ja053277d.Wilson JE, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:1426–1429. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503312.

- 12.For a review of the use of chiral amines as enantioselective nucleophilic catalysts, see: France S, Guerin DJ, Miller SJ, Lectka T. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2985–3012. doi: 10.1021/cr020061a.

- 13.Notes: a) Dimerization of the ketene is sometimes observed as an undesired side reaction. b) The use of non-chlorinated solvents can lead to significant changes in enantioselectivity.

- 14.Notes: a) Use of diethyl, rather than dimethyl, azodicarboxylate for reactions of phenyl ethyl ketene and p-chlorophenyl isopropyl ketene led to 80% ee/85% yield (cf. entry 2 of Table 2) and 86% ee/96% yield (cf. entry 12 of Table 2), respectively. b) This method is not highly air- or moisture-sensitive: for a cycloaddition of phenyl ethyl ketene that was set up in the air with unpurified CH2Cl2, fairly good ee and yield were observed (83% ee, 77% yield). c) A reaction conducted on 1 g of phenyl ethyl ketene proceeded in 84% ee and 77% yield. d) For the conversion of one of these aza-β-lactams into a hydantoin and an α,α-disubstituted amino acid, see the Supporting Information.

- 15.Notes: a) We speculate that the dichotomy may be due to different stereochemistry-determining steps for the two processes. b) Product ee correlates linearly with catalyst ee. For a review of non-linear effects in asymmetric catalysis, see: Kagan HB, Luukas TO. Chapter 4.1 In: Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Springer; New York: 1999.