Abstract

EPR spectra of perdeuterated 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-oxopiperidine-1-oxyl (PDT) are studied as functions of molar concentration, c, and temperature, T, in water and 70 wt% glycerol in water. The increase of the intrinsic linewidth averaged over the three hyperfine lines, 〈Btot〉, varies linearly with c with zero intercept in both solvents at all temperatures; therefore is independent of c. The spin exchange induced dispersion, from which the spin exchange frequency, ωe, may be computed, increases linearly with 〈Btot〉, passing through the origin in water and in 70 % glycerol at high temperatures; however, at low temperatures, where dipolar interactions broaden the spectra, linearity does not prevail until 〈Btot〉 > 1 G due to a contribution of dipolar interactions to the dispersion. The broadening constant due to spin exchange, , is found from the slope of the linear region, permitting a computation of the dipolar constant, . Thus, the separation of concentration broadening into spin exchange and dipolar contributions is effected without having to appeal to some supposed temperature dependence of the two interactions. The fractional broadening by spin exchange, Ω(T), is near unity at high temperatures in both solvents, decreasing to zero in 70 % glycerol at 273 K. Ω(T) is a continuous function of the inverse rotational correlation time of PDT, but is discontinuous as a function of T/η where η is the shear viscosity. Ω(T) = 0.5, where spin exchange and dipolar interactions contribute equally to the linewidth occurs at T/η = 20 ± 1 K/cP in 70 % glycerol. Hydrodynamic predictions of via the Stokes-Einstein (SE) equation are remarkably accurate in 70 % glycerol comparable with the results in a series of alkanes. In water, is linear with T /η with zero intercept as required by the SE; however, with slope a factor of 0.73 smaller. is reasonably predicted by the SE only at very small values of η/T very quickly following an approximately logarithmic dependence rather that the linear prediction. Values of approach a plateau above η/T = 0.20 cP/K that is about one-half the solid state limit. Line shifts due to spin exchange are not yet useful to deduce values of Ω(T) due to a lack of knowledge of the time between re-encounters; however, they may be used to verify the values determined from line broadening and spin exchange induced dispersion. Some effects at low temperatures in 70% glycerol suggest that the effects of dipolar interaction are inadequately described by the widely accepted theory.

Introduction

This is a continuation of series of papers (Parts 1 – 5)1-5 whose ultimate goal is to measure the translational diffusion of nitroxide free radicals (nitroxides) in compartmentalized systems, such as micelles. We began the work 18 years ago6 thinking that the theory was complete:7 spin exchange broadened and shifted the resonance lines when and narrowed them in the opposite extreme, where ωe is the spin exchange frequency, A0 the hyperfine coupling constant in the absence of spin exchange, and γ the gyromagnetic ratio of the electron. It was thought that ωe could be derived from any one of these three effects7 and we thought that we could use a combination of the effects to deduce collision frequencies and statistical distributions of nitroxides in compartmentalized systems. However, the predicted line shifts turned out not to agree with experiment2,3,8-11 and the narrowing is not practical to use in most interesting cases,7 leaving line broadening as the only tool. It was known7 that the line shape departed from Lorentzian as ωe increased, so we turned our attention to that aspect of the problem and learned that the line shape could be expressed as a sum of two components, an absorption and a “spin exchange induced dispersion.”1 In Part 22 we showed that only two components were necessary to reproduce the EPR spectrum to very high values of ωe where was near unity and the lines coalesced into a single line and in Part 3 we proposed that the line shift discrepancy was due to re-encounter collisions.3 Part 44 provided a test of the line shift proposal and Part 55 studied re-encounters in a series of alkanes. In short, at high values of T /η, where T is the absolute temperature and η is the shear viscosity, we finally think that the theory is complete, although more work is needed to fully establish that the re-encounter mechanism is responsible for the line shift discrepancy.12 We refer the reader to Parts 1 – 5 and the references therein for extensive discussion.1-5 A major remaining problem arising as T /η decreases—separation of dipolar and spin exchange interactions—is the subject of the present work. This problem often occurs in the most interesting liquids and complex fluids because biologically important systems are often viscous enough to require such a separation.13 Applications of spin-spin interactions between nitroxides in biological and model membranes are numerous.14

Both spin exchange and dipolar interactions broaden EPR lines linearly with concentration.13 In the past, most of the efforts to separate the interactions had to rely on a supposed temperature dependence of the dipolar interaction often formulated from the Stokes-Einstein equation.13 Unfortunately, a paper published in 1979 by Berner and Kivelson13 showed that the line broadening method was not very promising because the linewidth did not show a hydrodynamic dependence at low values of T /η.

At first, our strategy to separate dipolar and spin exchange interactions was to measure spin exchange induced dispersion to deduce ωe, use this to compute the broadening due to spin exchange, and subtract from the total broadening to get the broadening due to dipolar interaction. Then we planned to use the line shifts to get an independent value of ωe to double check the procedure; however, this went awry as mentioned in the first paragraph. Therefore, we are left with just enough information to be able to separate the effects due to spin exchange and dipolar interactions at a single temperature not having to make any assumptions about the model of diffusion. Fortunately, we are able to utilize the line shifts to verify the results.

Theory

Heisenberg Spin Exchange

The theory has been presented in detail for EPR spectra due to 14N nitroxides undergoing spin exchange in low viscosity liquids.1-3,7 We briefly summarize the results and refer the reader to the literature for more details and discussion.1-5 The generally accepted expression describing the spectrum, given by Currin15 in 1962, predicts that the lines broaden, shift toward the center of the spectrum, and eventually merge into a single line as ωe increases. We call Currin's15 expression, derived by many workers,1 the “rigorous theory.” For a summary, see ref1 and the Appendix of the same reference1 for explicit expressions of the rigorous theory written for a first-derivative magnetic field-swept spectrum. The rigorous theory is in agreement with experiment not only for two- and three- but also for five-line spectra in every detail except one.2-4 The line shifts are larger than predicted in every case2-4 except one, aqueous solutions of Fremy's salt.1 We showed that the line shapes in the first-derivative field-swept form predicted by the rigorous theory were reproduced to high precision by a simple analytical expression valid all the way up through line coalescence as follows2-4

| (1) |

where, H is the swept magnetic field, SMI (H) is the absorption, and DMI(H) is a spin-exchange induced “dispersion.” The sum in eq 1 is over the nuclear quantum number MI = +1, 0, and −1, labeling the low-, central-, and high-field lines, respectively. Equation 1 is identical to eq 1 of ref2 except that the absorption of Lorentzian shape has been replaced by SMI (H) which is a Gaussian-Lorentzian sum function approximation to a Voigt shape given by eq 12 of ref16. The absorptions SMI (H) involve mixing parameters from which the separate Lorentzian and Gaussian contributions to the linewidths may be deduced and various parameters may be corrected for inhomogeneous broadening.16 Vpp is the peak-to-peak amplitude of the absorption and are the maximum values of DMI (H). The expression for DMI (H) is given by eq 10 of ref 2. The credit for the form of eq 1 ought to go to Molin et al.7 who worked out the perturbation theory predicting the second term. Our contribution was to apply the term to nitroxides, develop non-linear least-squares fitting software allowing us to measure it, and permit the parameters in the original perturbation theory to vary with ωe in order to preserve the simple form at high values of .1,2

Tables 1 and 2 give the results of fitting spectra generated by the rigorous theory to eq 1 for 14N and 15N nitroxides, respectively. Inhomogeneous broadening by unresolved hyperfine structure has no effect on the results in Tables 1 and 2.2

Table 1.

Results of fitting spectra generated by the rigorous theory to eq 1. (a) 14N nitroxides.

| Dispersion and line shifts. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| 0.037890 | 0.037986 | 0.99960 | 0.99960 | ||||||||

| 0.075781 | 0.076254 | 0.99838 | 0.99838 | ||||||||

| 0.11367 | 0.11508 | 0.99636 | 0.99637 | ||||||||

| 0.15156 | 0.15477 | 0.99352 | 0.99354 | ||||||||

| 0.18945 | 0.19575 | 0.98985 | 0.98991 | ||||||||

| 0.22734 | 0.23829 | 0.98536 | 0.98546 | ||||||||

| 0.26523 | 0.28292 | 0.98002 | 0.98021 | ||||||||

| 0.30312 | 0.32996 | 0.97382 | 0.97416 | ||||||||

| 0.34101 | 0.38077 | 0.96676 | 0.96729 | ||||||||

| 0.37890 | 0.43530 | 0.95881 | 0.95962 | ||||||||

| 0.41679 | 0.49497 | 0.94995 | 0.95114 | ||||||||

| 0.45468 | 0.56178 | 0.94018 | 0.94186 | ||||||||

| 0.49257 | 0.63783 | 0.92946 | 0.93176 | ||||||||

| 0.53046 | 0.72426 | 0.91779 | 0.92086 | ||||||||

| 0.56835 | 0.82784 | 0.90515 | 0.90915 | ||||||||

| 0.60624 | 0.95396 | 0.89153 | 0.89663 | ||||||||

| 0.64413 | 1.1147 | 0.87693 | 0.88331 | ||||||||

| 0.68202 | 1.3227 | 0.86137 | 0.86917 | ||||||||

| 0.71992 | 1.6183 | 0.84490 | 0.85423 | ||||||||

| 0.75781 | 2.0847 | 0.82759 | 0.83849 | ||||||||

| 0.79570 | 2.9274 | 0.80958 | 0.82193 | ||||||||

| 0.83359 | 4.9254 | 0.79107 | 0.80457 | ||||||||

| Broadening and intensities. | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

< Be > / A0 | Be(±) / Be (0) | I(±)b | I (0)b | I(±) / I(0)0 | ||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.33334 | 0.33334 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 0.037890 | 0.037880 | 0.037896 | 0.037891 | 1.0004 | 0.33307 | 0.33388 | 0.99757 | ||||

| 0.075781 | 0.075699 | 0.075822 | 0.075781 | 1.0016 | 0.33225 | 0.33550 | 0.99031 | ||||

| 0.11367 | 0.11339 | 0.11381 | 0.11367 | 1.0037 | 0.33088 | 0.33824 | 0.97823 | ||||

| 0.15156 | 0.15090 | 0.15189 | 0.15156 | 1.0066 | 0.32893 | 0.34214 | 0.96138 | ||||

| 0.18945 | 0.18815 | 0.19010 | 0.18945 | 1.0104 | 0.32636 | 0.34726 | 0.93981 | ||||

| 0.22734 | 0.22507 | 0.22848 | 0.22734 | 1.0151 | 0.32314 | 0.35370 | 0.91359 | ||||

| 0.26523 | 0.26159 | 0.26706 | 0.26524 | 1.0209 | 0.31920 | 0.36156 | 0.88283 | ||||

| 0.30312 | 0.29762 | 0.30588 | 0.30313 | 1.0278 | 0.31447 | 0.37099 | 0.84765 | ||||

| 0.34101 | 0.33306 | 0.34500 | 0.34102 | 1.0359 | 0.30887 | 0.38217 | 0.80820 | ||||

| 0.37890 | 0.36781 | 0.38446 | 0.37891 | 1.0453 | 0.30227 | 0.39532 | 0.76464 | ||||

| 0.41679 | 0.40175 | 0.42433 | 0.41681 | 1.0562 | 0.29456 | 0.41070 | 0.71720 | ||||

| 0.45468 | 0.43475 | 0.46468 | 0.45470 | 1.0688 | 0.28555 | 0.42866 | 0.66614 | ||||

| 0.49257 | 0.46664 | 0.50558 | 0.49260 | 1.0834 | 0.27505 | 0.44960 | 0.61177 | ||||

| 0.53046 | 0.49725 | 0.54712 | 0.53049 | 1.1003 | 0.26280 | 0.47399 | 0.55445 | ||||

| 0.56835 | 0.52636 | 0.58941 | 0.56839 | 1.1198 | 0.24853 | 0.50243 | 0.49465 | ||||

| 0.60624 | 0.55372 | 0.63258 | 0.60630 | 1.1424 | 0.23187 | 0.53561 | 0.43291 | ||||

| 0.64413 | 0.57904 | 0.67678 | 0.64420 | 1.1688 | 0.21242 | 0.57432 | 0.36986 | ||||

| 0.68202 | 0.60199 | 0.72217 | 0.68211 | 1.1996 | 0.18974 | 0.61945 | 0.30630 | ||||

| 0.71992 | 0.62216 | 0.76895 | 0.72002 | 1.2359 | 0.16338 | 0.67190 | 0.24316 | ||||

| 0.75781 | 0.63913 | 0.81735 | 0.75794 | 1.2788 | 0.13296 | 0.73240 | 0.18154 | ||||

| 0.79570 | 0.65242 | 0.86759 | 0.79587 | 1.3298 | 0.098316 | 0.80132 | 0.12269 | ||||

| 0.83359 | 0.66157 | 0.91992 | 0.83380 | 1.3905 | 0.059713 | 0.87812 | 0.068001 | ||||

Input values. Compare with column 7.

Fitting simulated spectra to eq 1.

Computed from the perturbation values

Table 2.

Results of fitting spectra generated by the rigorous theory to eq 1. 15N nitroxides.

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 0.011364 | 0.015155 | 0.99982 | 0.99981 | ||||

| 0.022727 | 0.030326 | 0.99923 | 0.99923 | ||||

| 0.034091 | 0.045530 | 0.99827 | 0.99826 | ||||

| 0.045455 | 0.060802 | 0.99691 | 0.99690 | ||||

| 0.056818 | 0.076124 | 0.99514 | 0.99516 | ||||

| 0.068182 | 0.091555 | 0.99300 | 0.99303 | ||||

| 0.079545 | 0.10706 | 0.99045 | 0.99051 | ||||

| 0.090909 | 0.12276 | 0.98755 | 0.98760 | ||||

| 0.10227 | 0.13857 | 0.98418 | 0.98431 | ||||

| 0.11364 | 0.15456 | 0.98045 | 0.98063 | ||||

| 0.12500 | 0.17074 | 0.97627 | 0.97656 | ||||

| 0.13636 | 0.18710 | 0.97173 | 0.97211 | ||||

| 0.14773 | 0.20368 | 0.96673 | 0.96727 | ||||

| 0.15909 | 0.22069 | 0.96127 | 0.96204 | ||||

| 0.17045 | 0.23795 | 0.95541 | 0.95642 | ||||

| 0.18182 | 0.25547 | 0.94914 | 0.95041 | ||||

| 0.19318 | 0.27332 | 0.94236 | 0.94402 | ||||

| 0.20455 | 0.29156 | 0.93514 | 0.93724 | ||||

| 0.21591 | 0.31033 | 0.92745 | 0.93007 | ||||

| 0.22727 | 0.32973 | 0.91927 | 0.92252 | ||||

| 0.23864 | 0.34928 | 0.91059 | 0.91458 | ||||

| 0.25000 | 0.36999 | 0.90141 | 0.90625 | ||||

| 0.26136 | 0.39069 | 0.89168 | 0.89753 | ||||

| 0.27273 | 0.41272 | 0.88141 | 0.88843 | ||||

| 0.28409 | 0.43512 | 0.87055 | 0.87894 | ||||

| 0.30682 | 0.48331 | 0.84709 | 0.85879 | ||||

| 0.31818 | 0.50850 | 0.83445 | 0.84814 | ||||

| 0.32955 | 0.53506 | 0.82109 | 0.83710 | ||||

| 0.34091 | 0.56311 | 0.80705 | 0.82567 | ||||

| 0.35227 | 0.59276 | 0.79227 | 0.81386 | ||||

| 0.36364 | 0.62421 | 0.77673 | 0.80165 | ||||

| 0.37500 | 0.65721 | 0.76036 | 0.78906 | ||||

| 0.38636 | 0.69319 | 0.74309 | 0.77608 | ||||

| 0.40909 | 0.77295 | 0.70564 | 0.74897 | ||||

| 0.43182 | 0.86739 | 0.66377 | 0.72030 | ||||

| 0.45455 | 0.98294 | 0.61659 | 0.69008 | ||||

| 0.47727 | 1.1309 | 0.56268 | 0.65832 | ||||

| 0.50000 | 1.3333 | 0.50000 | 0.62500 | ||||

| 0.52273 | 1.6416 | 0.42458 | 0.59013 | ||||

| 0.54545 | 2.2188 | 0.32778 | 0.55372 | ||||

| 0.56818 | 4.2669 | 0.17753 | 0.51575 |

Input values. The broadening measured from the simulated spectra yields values of that are within 10-8 of .

Fitting simulated spectra to eq 1.

Computed from the perturbation values .

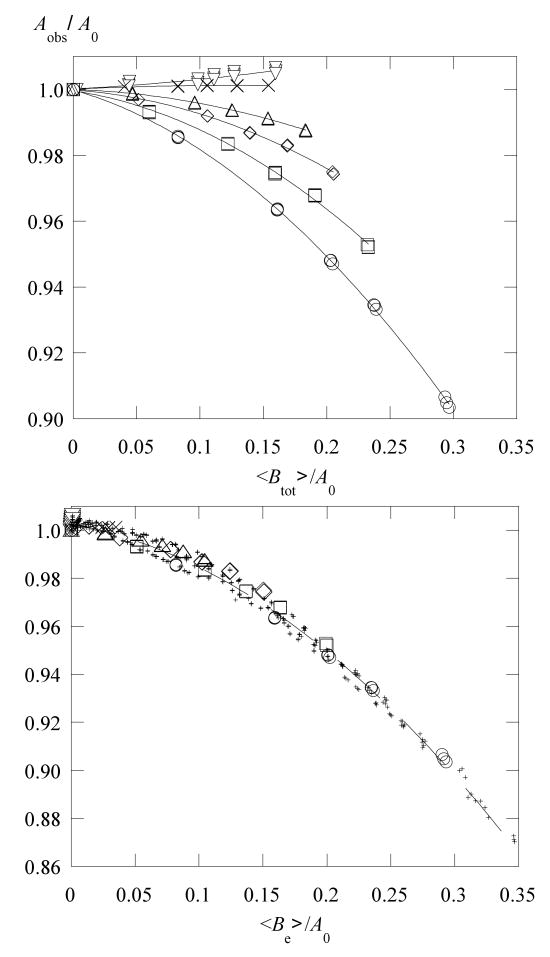

In a conventional first-derivative presentation, such as that in Figure 1 below, where the integrated spectrum is positive, , while for the center line . The ratios are monotonic functions of that are well approximated by the following:

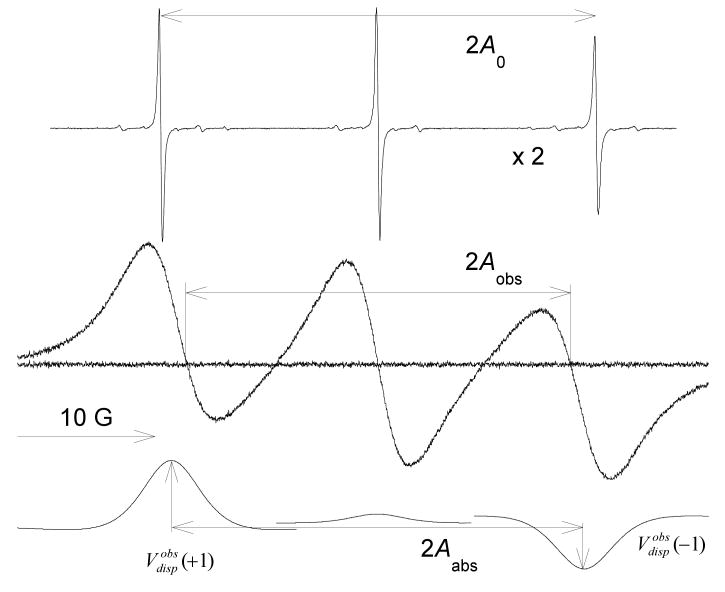

Figure 1.

EPR spectra due to 0.1 (top trace, at a relative gain of ×2) and 93.6 mM (middle trace) PDT in 70% glycerol at 343K. The fit of the middle trace to eq 1 is indistinguishable from the spectrum; the spectrum minus the fit gives the residual shown as the noisy baseline. The fit gives 3 absorption (not shown) and 3 dispersion lines that are given the lower trace. This is the “standard” presentation of the spectrum, yielding a positive absorption spectrum upon integration. The dispersion component on the central line is due to an imbalance in the microwave bridge; the component at low-field with a maximum value, , and the one at high-field with are expected from exchange. Exchange shifts the lines toward the center, resulting in line spacings 2Aobs and 2Aabs that are less than the spacing 2A0 observed in the absence of exchange. The spectrum is dominated by exchange; the fractional broadening by spin exchange is Ω(T) = 1.004 ± 0.021.

| (2) |

The leading term in eq 2 is predicted by perturbation theory1,7 and the second, found by fitting the values in Tables 1 and 2, corrects3 to within 0.5% for . For more precision or to find higher values of , interpolation of the values in Tables 1 and 2 may be employed.

In addition to the spin exchange induced dispersion component in eq 1, an “instrumental” dispersion component due to an imbalance in the microwave bridge often appears in the spectrum that may be corrected as follows:4

| (3) |

There are two independent values of the right-hand side of eq 2, which we abbreviate as follows:

| (4) |

To save space, we shorten the terms “spin-exchange induced dispersion” to “ exchange dispersion,” spin exchange to “exchange,” and dipolar interactions to “dipolar” when the meaning is clear.

Dipolar

The effect of dipolar on spin relaxation in liquids at large values of T/η where motional narrowing theory is expected to hold, has been available for many years17 and applied to electron spins at X-band.13 The effect of dipolar in the static limit where T/η approaches zero, is also known.13 In both of these limits, the lines are Lorentzian in shape and broaden linearly with the molar concentration, c. In recent years, Nevzorov and Freed have bridged the gap between the motional narrowing regime and the rigid limit by considering coupled systems of two spins18 and many-body systems.19 These later theories have not yet advanced to the point of being applicable to nitroxides; however, they confirm that the lines broaden in proportion to c and are approximately Lorenztian.

Assumptions

Thus, summing up the older theories, we assume that dipolar

produces broadening that is proportional to c and is independent of MI;

produces Lorentzian lines;

contributes neither to Vdisp; nor to

line shifts; and

does not alter the relative intensities of the three lines.

The above assumptions follow from the widely accepted theory of the equations of motion of the transverse components of magnetizations that include only secular terms thereby preventing coherence transfer that is responsible for the interesting effects in spin exchange outlined above. We are indebted to one of the referees who called our attention to more recent work20 where the authors argue that nonsecular terms are required in the dipolar interaction. Such terms would, in principle, also lead to dispersion, line shifts, etc.; however, with the important difference that the signs of the dipolar nonsecular terms are opposite to those for spin exchange. The theory is not yet available for the three-line case pertinent to nitroxides; however, qualitatively, the lines are expected to shift toward one another and merge, but not narrow as the dipolar interaction increases.20 Dispersion terms are expected of opposite sign to those under spin exchange. These two manifestations of dipolar interactions would negate assumptions 3 and 4. We do not yet know whether the second part of assumption 1 or assumption 5 are would be negated. The arguments in ref 20 seem sound; however, we do not know of any experimental confirmation of the details of the theory. In this work, we are unable to confirm the theory but find intriguing evidence in favor of some of its aspects, which offers some interesting prospects for future work.

Separation of Exchange and Dipolar

The broadening of the MI line is computed from

| (5) |

where and are the peak-to-peak intrinsic Lorentzian linewidths in the presence and absence of concentration broadening due to exchange and dipolar, respectively. Exchange broadens the MI = ±1 lines slightly faster than the MI = 0 line (Table 1).3 We define with <Btot > similarly defined. Line broadening due to the two interactions are additive,13 thus

| (6) |

Exchange broadens the lines as follows:

| (7) |

Because both dipolar and exchange broaden the lines linearly with concentration, at a given temperature in a given solvent, the factional broadening by exchange

| (8) |

is expected to be independent of the molar concentration, c. Near c = 0, it has been observed that linearity breaks down so following Berner and Kivelson,13 we take the derivative of eq 6 with respect c and employ eq 7 to write

| (9) |

In terms of the broadening constants , , and , we write from eq 9

| (10) |

The terms on the right-hand side of eq 10 are measured directly and independently allowing us to deduce . Note that the commonly quoted second-order spin exchange rate constant7 may be computed as follows: .

In the region in which Ω(T) is constant versus c, we may write

| (11) |

In eq 11, uncertainties in c and in the temperature yield uncertainties in Ω(T) that can be minimized by observing that

| (12) |

Therefore, independent measurements of the total broadening and the dispersion amplitude yield two independent values of Ω(T)±. Note that assumptions 1 and 3 are employed in the derivation of eq 12.

In principle, line shifts could also be used to provide another independent measure of ωe although of slightly lower precision.1 There are two shifts: one that decreases the spacing between resonance fields, Aabs; the other that decreases the spacing between the fields where the spectrum crosses the baseline, Aobs. See Figure 1, where 2Aabs is depicted as the spacing between the maxima of the dispersion features; however, it is also the spacing between the absorption lines that are not shown. Aabs cannot be measured directly from the spectrum; it must be deduced from a fit to eq 1. The shifts leading to Aobs are about a factor of three larger than those leading to Aabs. See earlier papers for explicit expressions for these spacings as predicted by perturbation theory.1 The expressions for Aabs are given in the footnotes to Tables 1 and 2. Note that the difference between the perturbation theory predictions of Aabs and the rigorous values are extremely small (compare columns 3 and 4 of Tables 1 and 2, respectively). The rigorous theory does not include the effect of exchange due to re-encounter collisions and is not in agreement with experiment except in one case, Fremy's salt.1 The expression for Aabs, modified by inclusion of a parameter describing the effect of re-encounters on the line shifts, , where τRE is the mean time between re-encounter collisions is given in eq 8 of ref4 while the same modification of Aobs is as follows:

| (13) |

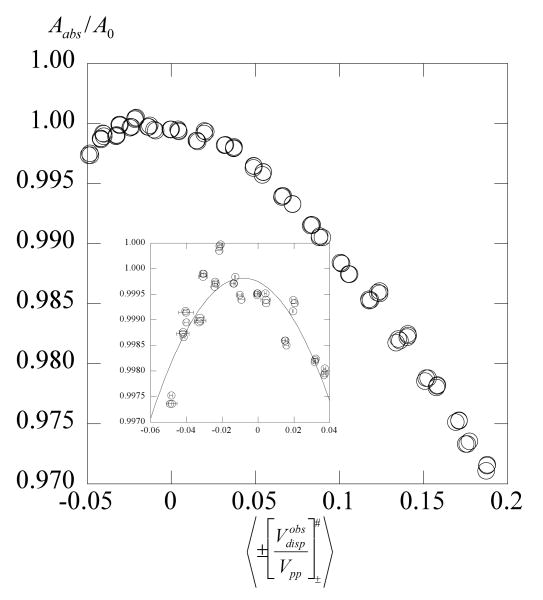

where is the average Lorenztian linewidth of the low- and high-field lines in the unbroadened spectrum. The additional term, , applies only in the case of strong exchange; i.e., when ωe is near the collision frequency.12 We have focused almost entirely on Aabs in recent work because the effect due to re-encounter exchange is a larger fraction of the total shift, allowing us to study re-encounters.3-5 Here, our motive is different: we wish to study Aobs because the term is quickly dominated by the final term in eq 13 masking the small temperature dependence of κ.4 Therefore, a plot of vs. will yield a universal curve for all temperatures and concentrations except near the origin. This will provide an independent check on the values of Be obtained from measurements of .

The translational diffusional coefficient of a Brownian particle diffusing in a bulk liquid, is given in the hydrodynamic limit by the Stokes-Einstein (SE) relation

| (14) |

where a is the effective hydrodynamic radius and k the Boltzmann constant. Utilizing the SE relation, Berner and Kivelson13 showed that

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

for low values of η/T and

| (17) |

in the solid state limit as η/T → ∞. For nitroxides, evaluating the constants in Berner and Kivelson's13 eqs 8, 10, and 11, Ce = 0.485cP·G/M·deg, Cdip =763deg·G/cP·M, and , In evaluating Ce, we have assumed that the distance for exchange interaction is equal to the hydrodynamic diameter of the probe.

Experimental

PDT (lot # A559P2, perdeuterated 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-oxopiperidine-1-oxyl, 97 atom % d) was purchased from CDN Isotopes and used as received. ACS reagent glycerol (99.8%) was obtained from Sigma and used as received. Stock solutions of 19.9 mM in water and 93.6 mM in 70 wt% aqueous glycerol were prepared in MilliQ water by weight and diluted. Undegassed samples were sealed into 50-μL pipettes and placed into sample tubes housed in Bruker's nitrogen gas-flow temperature control dewar. The accuracy of the concentrations is estimated to be ± 3% and the relative concentrations ± 1%. The temperature, accurate to ± 1 K, was measured with a thermocouple placed just above the active portion of the microwave cavity. During each spectrum, the temperature was stable to ± 0.1 K. Three EPR spectra were acquired, one after the other, with a Bruker 300 ESP X-band spectrometer interfaced with Bruker's computer employing a sweep time of 41 s; time constant, 10 ms; microwave power, 5 mW; sweep width, 50.2 G; and modulation amplitude, 0.2 G. The magnetic sweep width was measured with Bruker's NMR Gaussmeter operating in the 1-mG resolution mode and was averaged over a day's run. At low concentrations, the line shapes were accurately described by the Gaussian-Lorentzian sum functions, SMI(H) from which the peak-to-peak Lorentzian, , and Gaussian, , line widths were determined and line height ratios were corrected for inhomogeneous broadening.16 Least-squares fits of the spectra were carried out as detailed previously.1-3 The Gaussian components, due to unresolved hyperfine couplings and the effect of field modulation yielded . After correcting for field modulation,21 unresolved hyperfine structure contributed 0.088 G to .

Results

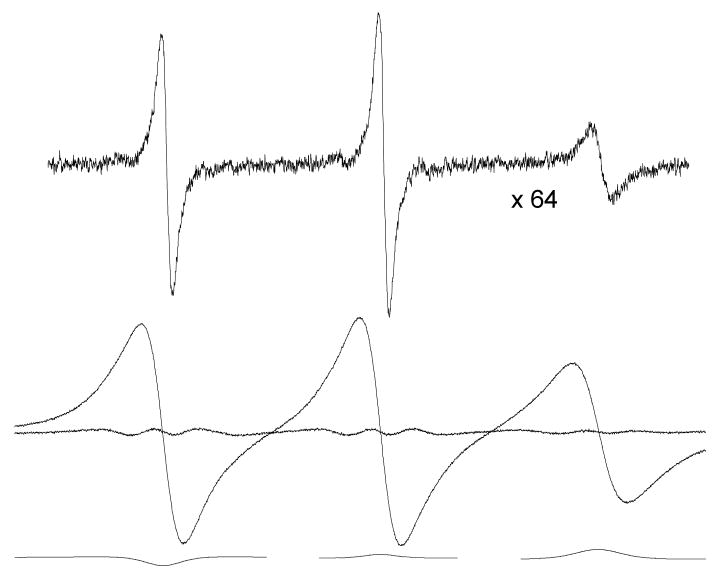

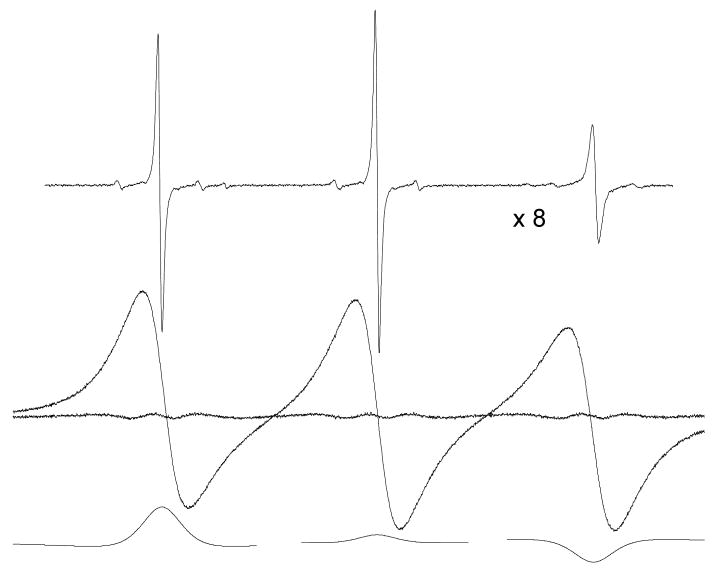

Figures 1 – 3 show experimental spectra of 0.1 mM (first trace) and 93.6 mM (second trace) PDT in 70% glycerol at 343, 293, and 273 K, respectively. Fits of the second traces to eq 1 are indistinguishable from the spectra on the scales of Figures 1 – 3. The residuals, the spectra minus the fits, are shown as the noisy baselines. The third traces are the dispersion components of the fits. The spectrum and residual in Figure 1 may be compared with spectra of other nitroxides in various solvents at high values of T/η where exchange dominates in Figure 2 of ref1 and Figures 2, 4, and 5 of ref2. Spectra simulated from the rigorous theory and their fits to eq 1 are given in Figure 1 of ref1 and Figure 1 of ref2. In earlier publications, we have displayed all of the components of eq 1; here, we omit the absorption components to save space. In Figure 1 and even up to much higher values of ωe /γ leading to coalescence of the hyperfine lines into a single line,2 only the absorption and dispersion components in eq 1 are needed to describe the spectra leading to undetectable differences in the spectra and the fits. Thus, the line shapes employed eq 1, Lorentzian-Gaussian sum functions at low values of ωe /γ and Lorentzian functions at high values, are in excellent agreement with experimental results.

Figure 3.

EPR spectra due to 0.1 (top trace, at a relative gain of ×64) and 93.6 mM (middle trace) PDT in 70% glycerol at 273 K. The fit and spectrum are indistinguishable; however, a definite residual is evident. Furthermore and the reverse of the signs expected from exchange. The contribution of exchange is negligible, Ω(T) = 0.006 ± 0.018.

In Figures 2 and 3, in contrast to the near-perfect fits in cases where exchange dominates, we observe that fits to spectra exhibiting significant dipolar broadening show definite residuals demonstrating that there are departures of the line shape from Lorentzian. The departures are not large; in the worst case, better than 97% of the doubly-integrated intensity of the spectra is accounted for by the Lorentzian shape. Nevertheless, an uncertainty that is difficult to estimate is introduced due to the residual. The fits to the spectra in Figures 1 - 3 lead to ; thus, if the imperfect fits are due to inhomogeneous dipolar broadening, such broadening is not detected as being Gaussian. Note that the central lines in Figures 1 – 3 show dispersion components due to microwave bridge imbalances; these are used to correct the dispersion amplitudes using eq 3. Also, at 273 K, note the curious inversion of the dispersion components giving negative values at low field and positive at high, opposite of that expected from exchange. Note that the previous sentence was written before we received the input from one of the referees suggesting that negative values could be expected from a more accurate theory of dipolar.20 Fitting low-temperature spectra such as that in Figure 3 with only absorption components (setting Vdisp (MI) = 0) yields residuals that are very similar to those in Figure 3; i.e., the line shape error is predominantly due to the absorption.

Figure 2.

EPR spectra due to 0.1 (top trace, at a relative gain of ×8) and 93.6 mM (middle trace) PDT in 70% glycerol at 293 K. The fit and spectrum are indistinguishable; however, a definite residual is evident due to a significant dipolar interaction; the fractional broadening by spin exchange is Ω(T) = 0.30 ± 0.03.

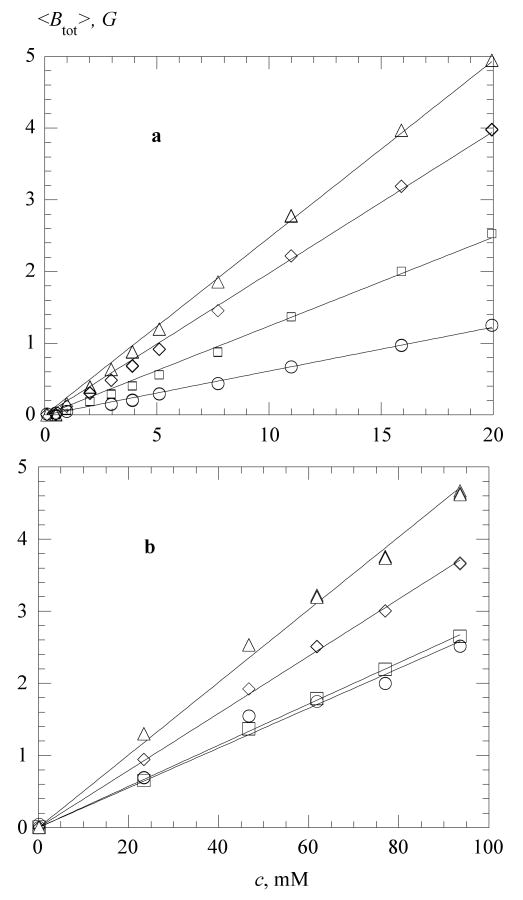

Figure 4 shows representative values of <Btot > at various temperatures as functions of c in water (4a) and in 70 % glycerol (4b); the straight lines are linear least-squares fits. In water, the coefficients of correlation, r, are better than 0.999 at all temperatures, while in 70 % glycerol the correlation is less satisfactory declining to reach a low of r = 0.986 at 273 K.

Figure 4.

Total linewidth versus PDT concentration (a) in water, at 268 K, ○; 298 K, □; 323K, ◊; and 338 K, △; and (b) in 70% glycerol, at 273 K, ○; 298 K, □; 323K, ◊; and 338 K, △. The straight lines are linear least-square fits constrained to the origin. The slopes are plotted in Figure 5. Coefficients of correlation, r, are larger than 0.999 at all temperatures in water. In 70 % glycerol, r = 0.986 (273 K), r >0.999 (298 and 323 K), and r = 0.986 (338 K).

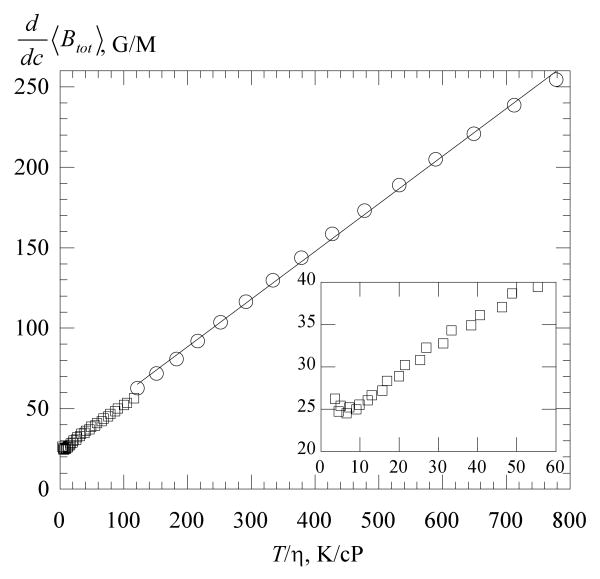

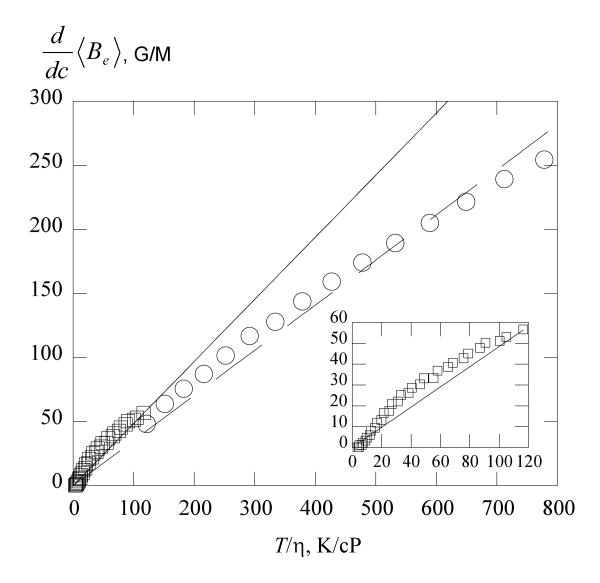

The slopes of the total broadening, , are given in Figure 5 as functions of T /η. In water, these slopes are linear with T/η; however, they do not extrapolate to the origin. In 70 % glycerol, shows an upturn as T /η decreases toward the origin as shown by the inset. In Figures 4 – 7 and 11, data from three spectra taken one after another are plotted separately to show the reproducibility. The appearance of a single datum means that the differences are too small to perceive on the scale of the figures.

Figure 5.

Total broadening constant versus for water, ○; and 70% glycerol, □. The straight line through the water data is a linear least squares fit yielding T / η in G/M with η in cP and r = 0.999. The data in 70 % glycerol show an upturn at low values of T / η (inset).

Figure 7.

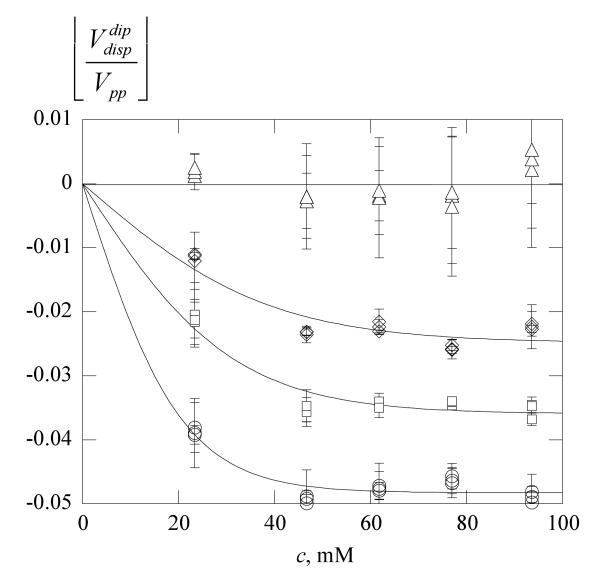

Dipole-induced dispersion in 70% glycerol versus concentration. Same symbols as Figure 6b. The average value from eq 20 is plotted; the error bars are one-half the difference. The solid lines are least-squares fits to eq 8 with c* = 0, 21, 31, and 39 mM from high to low temperature, respectively. The plateau values and −0.048, respectively.

Figure 11.

The observed line spacing of PDT in 70% glycerol versus (a) the total line broadening at 273 K, ▽; 292 K, ×; 307 K, △; 313 K, ◊; 323 K, □; and 342 K, ○; and versus (b) the exchange line broadening employing the same symbols. Data at all other temperatures are plotted in (b) as small plus signs. In (a), the solid lines are quadratic fits to guide the eye at each temperature and in (b) the dashed line is the fit of all data to eq 13. Equation 13 predicts a common curve versus the exchange broadening away from the origin as is observed.

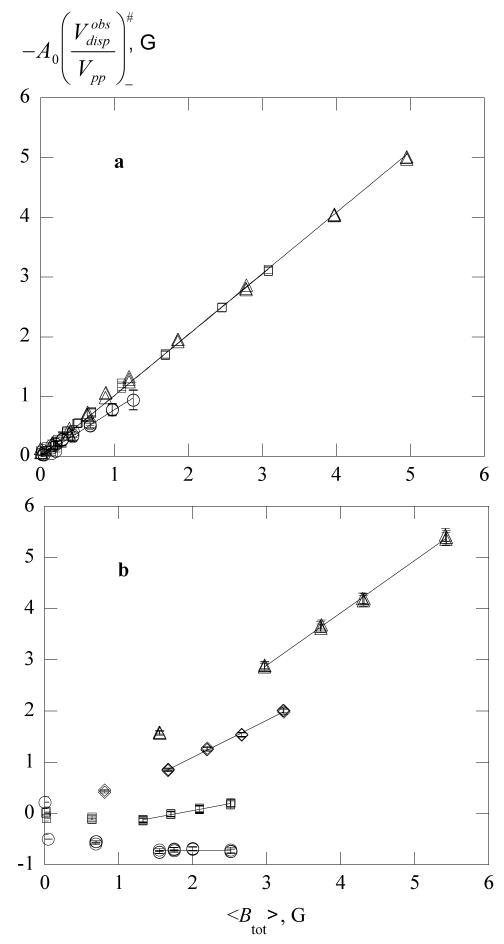

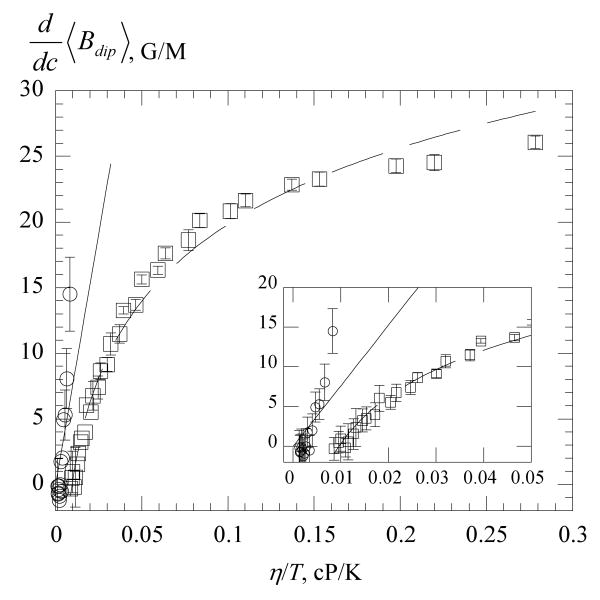

Figure 6 displays values of , corrected using eq 3, as functions of Btot where the superscript obs denotes the observed value; i.e., that emerging from the fit to eq 1. Plots of (not shown), are very similar to Figure 6; the error bars show one-half the difference in the two values. In water, Figure 6a, the plots are, as expected, straight lines of slope approximately equal to unity at higher temperatures, demonstrating that . In contrast, in 70 % glycerol at lower temperatures, Figure 6b, plots of do not become linear until Btot > 1 G. Additionally, at lower temperatures, and both become negative which cannot come from exchange. The straight lines in Figure 6a are linear least-squares fits constrained to the origin and in Figure 6b are fits to the highest 4 concentrations.

Figure 6.

Values of versus the total broadening in (a) water at 268 K, ○; 303 K, □; 338K, △; and in (b) 70% glycerol at 273 K, ○; 293 K, □; 313K, ◊; and 352 K, △. The straight lines through the water data are linear least-squares fits constrained to the origin (r = 0.999, 303 and 338 K; r = 0.991, 268 K). Those through the 70% glycerol data are linear least-squares fits to the highest 4 concentrations (r = 0.994, 293 K; r = 0.998, 313 K; and r = 0.999, 352 K). In water at all temperatures and in 70 % glycerol above 323 K, linear fits constrained to the origin using all concentrations yield the same slopes as those using the highest four not constrained to the origin. Plots of (not shown) are similar. The error bars are one-half the difference in . Were it not for a dipolar contribution to the dispersion, the ordinate would be the broadening due to exchange, Be, eq 7.

Clearly, the results in Figure 6b do not conform to assumption 3, that dipolar interactions do not contribute to the dispersion for values of Btot near the origin. It is not clear from the fits whether (1) dipolar yields negative values of or (2) the imperfect fits evident in Figures 2 and 3 lead the search in parameter space to non-physical values. The input received from one of the referees suggests that (1) might be expected. Note that the correction term in eq 4 is negligible for the negative values so we drop the superscript #. If possibility (1) holds, then we conclude that the dipolar dispersion is not linear in c reaching a plateau at rather low values of 〈Btot〉. If possibility (2) holds, then the fact that even when these quantities are negative, is a curious coincidence. In either case, we may write

| (18) |

where the superscript dip refers to the dipolar contribution be it due to possibility (1) or (2). The data in Figure 6b and at all other temperatures show that values of achieve constant values away from the origin; thus, for these higher values of Btot, , and

| (19) |

allowing us to evaluate Ω(T)± from eq 12 and Be from eq 8.

Therefore, from eq 18

| (20) |

Figure 7 shows values of , which are average values of ; the error bars are the standard deviations of the two values. The dipolar contribution to the observed dispersion reaches a plateau above 40 mM. The solid lines in Figure 7 are non-linear least-squares fits to

| (21) |

where the constant is the plateau value at large c and c* is a characteristic concentration at which the plateau is approached. There is no theoretical basis for eq 21; for now, we use it as a guide to the eye in Figure 7. For possible future reference, we plot the values of the constants and c* in the Supplemental Information.

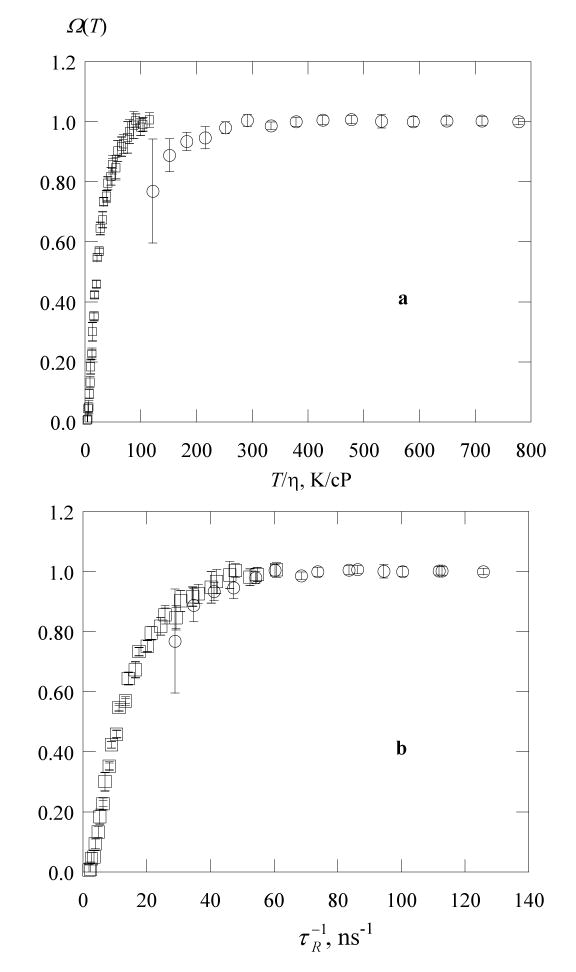

Guided by the SE, eq 14, reasoning that at equal values of the diffusion coefficient, Ω(T) ought to be the same, we plot values of Ω(T) (the average of Ω(T)±) versus η/T in Figure 8a for the two solvents showing that the fractional broadenings by exchange are not accurately predicted by the SE in different solvents. Interestingly, there is enough information in the EPR spectrum to pursue the matter further. The rotational correlation time, τR, was computed from line-height ratios using standard formulas22 and corrected for inhomogeneous line broadening.16 According to the Stokes-Einstein-Debye relation, τR is proportional to η/T. In complicated solvents, neither D nor is proportional to T/η; however, their ratio is constant.10,23 In other words, the departures from the SE are similar for translation and rotation. This fact motivates the plot in Figure 8b in which values of Ω(T) are plotted versus showing that the transition between the two solvents is continuous. Robinson et al.10 write a modified SE employing a viscosity to a power < 1 to unify the results. Another possible reason for this discrepancy might be the effect of steric hindrance on the spin exchange. Due to hydrogen bonding, the steric hindrance factor value7 and thereby the efficiency of spin exchange may be affected by the solvation of the NO group in water more than in the water-glycerol mixtures.

Figure 8.

Fractional broadening by exchange of PDT in water, ○; and in 70% glycerol, □; versus (a) T / η and (b) the inverse rotational correlation time. The error bars are one-half the difference in the values of Ω(T)±. In 70% glycerol, exchange and dipolar broadening are equal at T / η = 20 ± 1 K/cP which corresponds to η = 15 cP at 300 K.

Figure 9 shows values of as a function of T /η in the two solvents. The solid line is the SE prediction computed from eq 15, while the dashed line is a linear least-squares fit to the data in water yielding Ke = (0.352 ±0.001)T /η with r = 0.978. The SE is reasonably accurate in predicting vales of in 70% glycerol as shown by the inset to Figure 9. The results in the inset are very similar to those from PDT in a series of alkanes: see Figure 5 of Part 5.5 In water the ratio . Berner and Kivelson13 observed a similar result for di-tert-butyl nitroxide in water where and pointed out that a difference in the hydrodynamic diameter of the probe and the exchange interaction distance in water could rationalize the result.

Figure 9.

Exchange broadening constant of PDT versus T / η in water, ○ and 70% glycerol, □. The solid line is the SE prediction, eq 15 and the dashed line is a linear least-squares fit to the water data.

Values of computed from eq 10 using the results in Figures 4 and 9 are plotted versus η/T in Figure 10. The straight line is the SE prediction, eq 16. The inset shows the results near the origin where the data in water are seen to be in reasonable agreement with the SE and the initial slope in 70% glycerol is also in reasonable agreement. The data in 70% glycerol rather quickly saturate, reaching only about one-half of the predicted static limit of 49.03G/M, eq 17. The solid line through the 70% glycerol data is a linear least squares fit of the data to a logarithm yielding in G/M with η in cP. The transition from low values of η/T to the static limit has been studied theoretically by Nevzorov and Freed18,19 for a simplified system in which no hyperfine structure is include. Also, their treatment does not include various averaging effects, so their results can only be viewed qualitatively; nevertheless, Figure 6 of ref19 shows that dipolar broadening decreases logarithmically with D. Near the static limit, the dipolar broadening becomes inhomogeneous.19

Figure 10.

Dipolar broadening constant versus η/T of PDT water, ○ and 70% glycerol, □. The solid line is the SE prediction, eq 16 and the dashed line is a linear least-squares fit of the 70% glycerol data to a logarithm. At 300 K, sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles fall at approximately 0.02 cP/K24 and model membranes at about 0.21 cP/K.14

Values of Aobs / A0 for PDT in 70% glycerol are plotted versus 〈Btot〉 / A0 in Figure 11a and versus 〈Be〉 / A0 in Figure 11b where Be is computed from eqs 19 and 8. The solid lines in Figure 11a are quadratic fits to guide the eye; in Figure 11b the dashed line is a fit of all of the data to eq 12 yielding κ = −0.045 ± 0.001. The data at temperatures represented in Figure 11a are represented by the same symbols in 11b. All of the rest of the data are shown by small plus signs. Note in Figure 11a, at lower temperatures, where the dipolar interaction dominates, Aobs / A0 actually increases slightly with Btot / A0 in contradiction to assumption 4 that dipolar interactions do not contribute to the line shifts. The formation of a common curve in Figure 11b supports the methods to evaluate Ω(T) and Be.

Discussion

Our goal in this work was to demonstrate a simple means to separate exchange and dipolar based on the EPR line shape, not appealing to any supposed temperature dependence of the interactions. According to the assumptions, arising from older motional-narrowing theory, Figure 6b would have been a series of straight lines passing through the origin, and only two samples at high- and low-concentrations would be required; however, that simplicity has thus far eluded us. Obtaining the data in Figure 6b requires extensive sample preparation, data collection, and analysis. One can separate dipolar and exchange, but it is not yet simple. If, indeed the theory in ref 20 proves to be an accurate representation of the experimental results, the separation will be complicated, however, with the added benefit of more information derived from the dipolar. We also carried out an extensive investigation employing 15N PDT in 70 % glycerol at concentrations up to 85 mM which we are unable to report because that concentration is not sufficient to reach the linear portions of plots such as Figure 6b. Despite there being some advantages to using 15N spin probes, they are inferior in these types of studies for several reasons: (1) for the same concentration, values of Be are smaller by a factor of 3/4 because only collisions between different values of MI produce broadening, (2) exchange dispersion which is a function of Be / A0 is reduced by a factor of 1.4 because the hyperfine coupling constant is larger by that factor, and at least as important (3) one does not have the redundancy in the exchange dispersion at high- and low-fields as a measure of the uncertainty or the central line to correct instrumental dispersion. Nevertheless, we note that in the testing stages of the theory in ref 20, these probes could be quite valuable because they would not present complications inherent in the second part of assumption 1 or in assumption 5.

Note that it is simple to detect the presence of dipolar by (1) preparing plots comparable to those in Figure 6 and looking for slopes less than unity or (2) preparing plots such as those in Figure 11a and looking curves that do not fall on top of one another. The more demanding task is to quantitatively compute values of Ω(T).

The analysis requires non-linear least-squares fitting of the spectra to eq 1 which gives nearly perfect fits in the limit Ω(T) → 1 but poorer fits as Ω(T) decreases toward the dipolar limit Ω(T) → 0. These imperfect fits are due to our incomplete knowledge of the proper EPR shape of a line broadened by dipolar. There is a small, unknown component to the line shape in addition to the predominant Lorentzian shape. Interestingly, “Pake” doublets appear in the theoretical line shapes; see Figure 1 of ref18. Further, the lines are broadened inhomogeneously.18 We suspected that both of these would be detected by the fitting software as Gaussian contributions to the line shape; however, the best fits yield . The discrepancy in Figures 2 and 3 is small; however, the experimental line is higher in the wings than a Lorentzian, reminiscent of the result in solids; see, e.g., p. 135 of ref7.

Fortunately, the values of induced either by fitting to an improper line shape or by a true negative dipolar contribution, reach constant values at about < Btot >≈ 1 G allowing us to evaluate Ω(T) from the slopes of observed at higher values of < Btot > where the dependence is linear. That this approach is valid is supported by the fact that values of Aobs / A0 form a common curve when plotted against values of < Be > / A0 derived from those slopes (Figure 11).

Values of for PDT in 70% glycerol are in remarkable agreement with those predicted from hydrodynamic theory using eq 15. We were surprised by this result, because it was known that that the rotation of probes in aqueous solutions of glycerol did not follow the SE prediction very well.10 These data together with those published recently show that is very similar in hexane, decane, hexadecane, and now 70% glycerol. So far, only water is different in that although the variation with T / η is nearly linear and passes through the origin. It is known that in many instances the value of of a nitroxide is lower in water than aprotic solvents.7 The steric factor, which can be determined by both the structure of the nitroxide and the solvation of the NO group, can reduce the spin exchange efficiency of nitroxide collisions. It is possible that the discrepancy we observe in water is due to the solvation of NO.

The results in Figure 8a show that values of Ω(T) at a given value of T / η are solvent dependent in the case of water and 70% glycerol, so one cannot accurately predict its value from a knowledge of the viscosity of the system. Nevertheless, as a guide, using the results in 70% glycerol, dipolar and exchange contribute about equally (Ω(T) = 0.5) at T / η = 20 ± 1 K/cP which corresponds to η = 15 cP at 300 K. Typical micelles present microviscosities, as estimated from rotational correlation times of spin probes, as follows: sodium dodecyl sulfate and dodecyl trimethylammonium bromide, 5 – 7 cP;24 tetraalkylammonium dodecyl sulfate 6 – 8 cP;25 and a sugar-based dodecyl sulfate 20 – 28 cP.26 Therefore, exchange is expected to dominate in some micelles and dipolar in others.

Figure 10 shows that the SE, eq 16, overestimates the values of in 70 % glycerol even at small values of η/T while the predicted static limit, eq 17, is about a factor of two larger that the experimental result. The dependence of on η/T becomes decidedly non-linear rather near the origin which explains why efforts to fit line broadening due to exchange and dipolar using the sum of eqs 15 and 16 have failed in liquids13 and have led to discrepancies in model membranes.14 The discrepancies in predictions of eqs 16 and 17 and the experimental results are not unanticipated because the theoretical predictions are upper value estimates as emphasized by Molin et al.,7 because significant averaging of dipolar can occur by various mechanisms.

Dipolar begins to be significant even in water at lower temperatures. It has been impossible in the past, measuring only the linewidths to detect the onset of dipolar. Results like those in Figure 5 have misled workers through the years. For example, the marvelous linearity of with T / η in water seemed to show that dipolar was negligible; however, the non-zero intercept is revealing. Such a non-zero intercept has been observed and various suggestions have been proposed;27 however, comparing Figure 9, where does pass through the origin, with Figure 5 where does not, shows that neglect of even minor dipolar contributions can explain the apparent anomaly. Even in 70% glycerol, we observe a reasonably linear dependence of on T / η for T / η > 10 K/cP (inset, Figure 5), but again with a non-zero intercept, signaling a significant dipolar contribution.

Considering Figure 10, is the pessimism of Berner and Kivelson13 that EPR is not very promising to study diffusion still valid? Above about η/T = 0.1 cP/K, Kdip becomes rather insensitive to diffusion. A typical diffusion coefficient in a model membrane is 1 × 107 cm2/s; see ref14 and references therein. Using eq 14, employing a probe radius of 3.5 Å5 for PDT, this corresponds to η/T = 0.21 cP/K, which falls in a region where the dipolar line broadening is rather flat with respect to D, supporting their conclusion. Thus, in viscous liquids, it does not seem promising to study dipolar to estimate diffusion coefficients, nevertheless, one can still separate exchange and dipolar and rely on the well understood exchange. The precision obviously suffers as Ω(T) → 0.

Secondary effects of exchange

There are two “secondary” effects of exchange in the case of 14N nitroxides: As ωe increases, (1) the outer lines broaden slightly faster than the central line and (2) the doubly-integrated intensity of the center line increases at the expense of the outer lines (Table 1).1,2 The differential line broadening effect is small but easily measurable as shown in Figure 7 of Part 22 where the outer and central linewidths are plotted separately and compared with the rigorous theory. The differential intensity is also easily measurable and can be rather substantial. See Figure 6 of ref2 that shows a dramatic difference in the outer and central lines and Figure 7 that compares the differential intensities to the rigorous theory. In water and in 70% glycerol at higher temperatures, we find (not shown) these expected secondary effects. At low values of T / η, all three lines broaden equally and all three intensities are equal, within experimental uncertainty. This confirms assumptions 1 and 5. In principle, ωe, and therefore Ω(T), could be estimated by these secondary effects.

It would be very useful to find a theoretically sound additional line shape component when dipolar is significant. If the search for a better line shape continues, it may be worth keeping in mind the possibility of negative dipolar-induced dispersion, even though these results do not prove it. It will be straightforward to test proposed shapes by including them into an equation such as eq 1. Unfortunately, as we have learned from fitting exchange broadened lines, it is not straightforward to discover such a shape from residuals such as those in Figures 2 and 3.28 The non-linear least-squares fit finds a minimum in parameter space such that the residual does not resemble the missing component.28

Is the theory of ref 20 valid?

One of the referees believes that we have observed results predicted by ref 20 in contrast to assumptions 1 – 5. Reference 20 predicts that when dipolar dominates, negative values of arise and increasing Bdip causes lines to shift toward one another. Figure 12 where values of Aabs / A0 for 46.7 mM PDT in 70% glycerol 273 – 352 K are plotted as a function of the mean values of , shows both of these effects. At low temperatures, negative values of are correlated with line shifts toward the center as predicted by the theory in ref 20. Noting the scale of the ordinate in the inset to Figure 12 shows that we would not have much to work with using the present data even if we had the full theory in ref 20. Nevertheless the results in Figure 12 encourage the design of experiments extending to lower values of T / η and the development of the theory in ref 20 for three lines.

Figure 12.

Line shifts versus the observed dispersion for 46.7 mM PDT in 70% glycerol 273 – 352 K. The abscissa is the mean of values measured from MI = ± 1 corrected for instrumental dispersion; the error bars shown in the inset are the standard deviations. The solid line in the inset is a linear least-squares fit of the data to a quadratic. Spin exchange increases toward the right and dipolar toward the left. The lines shift toward one another both above and below the position of no shift near dispersion equal to zero. Negative values of the dispersion and line shifts toward the center of the spectrum at low temperatures are predictions of the theory in ref 20.

Conclusions

The most important result from this work is that dipolar and exchange may be separated, Figure 8, but not by studying the linewidth alone. Non-linear least-squares fits of the spectra to a model of absorption (Gaussian-Lorentzian sum functions) plus spin-spin interaction induced dispersion yield nearly perfect fits in the limit of Ω(T) → 1 and good, but not perfect fits in the opposite extreme Ω(T) → 0. From these fits, values of Ω(T) may be deduced from the slopes of the dispersion component with respect to 〈Btot〉 from which 〈Be〉 may be computed. Complicating the procedure, perhaps due to our imperfect knowledge of the proper line shape, is the fact that values of the dispersion do not become linear functions of 〈Btot〉 until 〈Btot〉 > 1 G. Nevertheless, by carrying out the measurements to sufficiently high values of c, one may eliminate the influence of dipolar on the dispersion. As expected, at high values of T / η, we find that exchange dominates while in the opposite extreme dipolar dominates. varies approximately linearly with T / η passing through the origin. The ratio of the values of to the SE prediction, is near unity for 70% glycerol and 0.73 for water. Perhaps unexpectedly, in 70% glycerol, variations of with η/T depart from linearity at rather low values following an approximately logarithmic dependence at higher values. This fact renders dipolar less useful to study diffusion than exchange. Results of line shifts and secondary effects – differential line broadening and line intensities – are consistent with the separation procedure. Negative values of accompanied by line shifts toward the center at low temperatures in 70% glycerol suggest that the effects of dipolar interaction are inadequately described by the widely accepted theory17 and could be explained by a more recent theory20.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from NIH grant 3S06 GM04680-10S1. We owe a debt of gratitude to two referees who obvious expended a great deal of effort to improve this paper and especially to one who alerted us to ref 20.

Footnotes

Suplemental Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bales BL, Peric M. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:8707. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bales BL, Peric M. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:4846. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bales BL, Peric M, Dragutan I. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:9086. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bales BL, Meyer M, Smith S, Peric M. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:2177. doi: 10.1021/jp7107494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurban MR, Peric M, Bales BL. J Chem Phys. 2008;129:064501. doi: 10.1063/1.2958922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bales BL, Stenland C. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:3418. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molin YN, Salikhov KM, Zamaraev KI. Spin Exchange Principles and Applications in Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 8 Springer-Verlag; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpern HJ, Peric M, Nguyen TD, Teicher BA, Lin YJ, Bowman MK. J Magn Reson. 1990;90:40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikonov AM, Nikonova SI. Sov J Chem Phys. 1991;7:2408. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson BH, Mailer C, Reese AW. J Magn Reson. 1999;138:210. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson BH, Mailer C, Reese AW. J Magn Reson. 1999;138:199. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salikhov KM. J Magn Reson. 1985;63:271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berner B, Kivelson D. J Phys Chem. 1979;83:1406. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachse JH, King MD, Marsh D. J Magn Reson. 1987;71:385. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currin JD. Phys Rev. 1962;126:1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bales BL. Inhomogeneously Broadened Spin-Label Spectra. In: Berliner LJ, Reuben J, editors. Biological Magnetic Resonance. Vol. 8. Plenum Publishing Corporation; New York: 1989. p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torrey HC. Phys Rev. 1953;92:962. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevzorov AA, Freed JH. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:1413. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevzorov AA, Freed JH. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galeev RT, Salikhov KM. Chem Phys Reports. 1996;15:359. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bales BL, Peric M, Lamy-Freund MT. J Magn Reson. 1998;132:279. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schreier S, Polnaszek CF, Smith ICP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;515:375. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(78)90011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovarskii AL, Wasserman AM, Buchachenko AL. J Magn Reson. 1972;7:225. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bales BL, Zana R. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:1926. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bales BL, Benrraou M, Tiguida K, Zana R. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:7987. doi: 10.1021/jp040728s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bales BL, Ranaganathan R, Griffiths PC. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:7465. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang JC, Freed JH. J Chem Phys. 1972;56:4103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peric M, Bales BL. J Magn Reson. 2004;169:27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.