Reversible acetylation plays a key role in defining chromatin states and in regulating transcription from genomic DNA differentially across distinct tissues.[1–3] Histone deacetylases (HDACs) function in this process by catalyzing the hydrolysis of N-acetyl groups on lysine residues found in the N-terminal tails of histone proteins.[4] This process mediates cell differentiation, correlates with epigenetic inheritance, and is deregulated in human disease, among others.[1–3, 5]

Identifying novel HDAC inhibitors is an increasingly active area of research.[6–10] Trapoxin, which is a naturally occurring HDAC inhibitor, was instrumental in the original discovery of HDAC1.[4] Suberoylaniline hydroxamic acid (SAHA/vorinostat), which inhibits multiple members of the HDAC family of enzymes, has been approved recently for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[11–13] Tubacin, which is the first homolog-selective inhibitor (having selectivity for HDAC6), has illuminated the function of HDAC6 and tubulin acetylation.[14–19]

Biochemical, enzyme-activity assays involving fluorescent readouts are frequently used to identify new HDAC inhibitors. However, this approach requires expensive reagents, equipment, and can be difficult to perform in a high-throughput manner. Small-molecule microarrays (SMMs) provide an attractive alternative for high-throughput identification of HDAC inhibitors. Currently, there are no reported uses of SMMs to identify new HDAC inhibitors, including ones having selectivity for specific members of the HDAC family. Traditional SMMs use various chemistries to attach compounds covalently.[20–25] Many of these approaches either take advantage of latent functionalities that result in heterogeneous molecular display on the surface, or require synthetic modification of compounds in order to obtain homogeneous display. Fluorous tags are versatile tagging groups for chemical library synthesis and can facilitate non-covalent immobilization on fluorinated glass surfaces.[26–31] A previous report from Pohl and coworkers demonstrated fluorous microarrays as a powerful screening tool for carbohydrate-binding proteins.[26] In this report, we demonstrate that fluorous-based SMMs enable the screening for HDAC inhibitors by allowing controlled molecular display of inhibitory functionality, low uniform background, and excellent signal-to-noise.

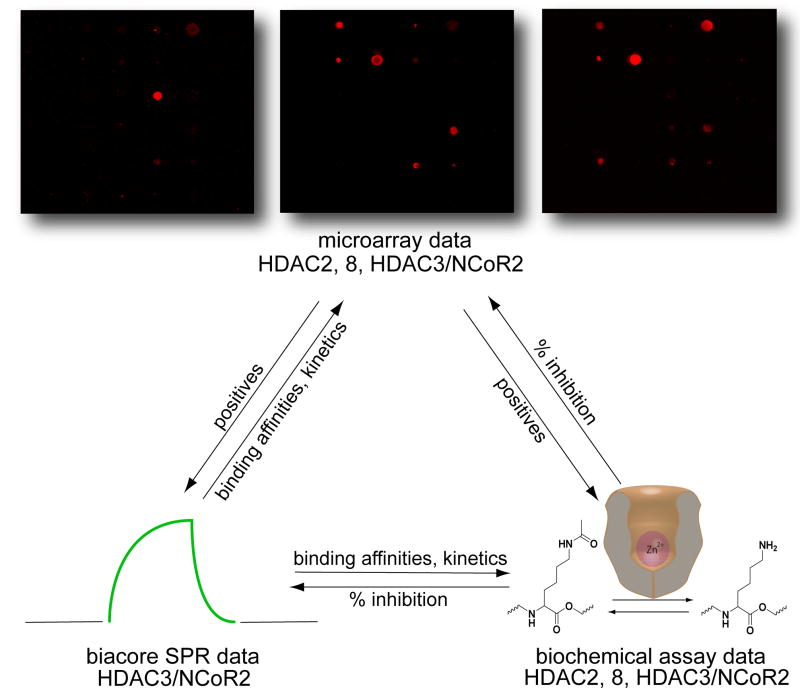

SMMs were evaluated as a tool for identifying HDAC binders or inhibitors using a three-part validation (Figure 1). Quantitative fluorescence data were collected from probed arrays and used to generate a list of positives. Non-fluorous tagged equivalents of the compounds were then tested in a fluorescence-based biochemical activity assay with the same set of enzymes to determine enzymatic inhibition. Furthermore, thermodynamic and kinetic binding data were collected for non-fluorous tagged compounds binding to one of the HDACs using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) methods.[32, 33] Finally, SMM binding data, biochemical activity data, and SPR data were compared to assess the accuracy of fluorous microarrays in identifying HDAC inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Experimental approach to validating the use of fluorous-based SMMs for HDAC inhibitor discovery.

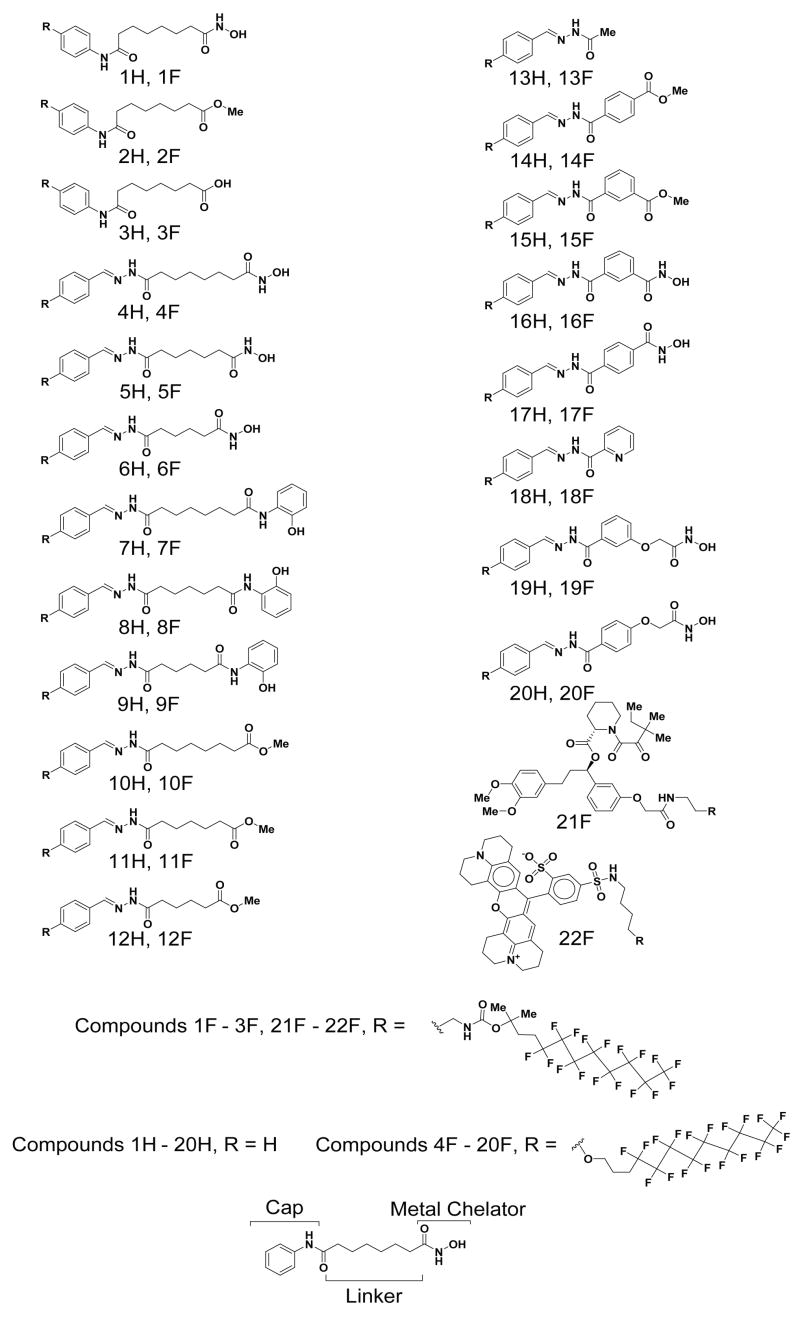

Microarrays were printed with a set of twenty fluorous-tagged molecules anticipated to be a mix of active and inactive inhibitors (Figure 2). Compounds 1F to 3F are fluorous-tagged SAHA analogues that serve as controls. The other 17 compounds are part of a collection of candidate HDAC inhibitors with varied linkers, metal chelators, and affinities.[34] Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and a fluorous-tagged compound known to bind FKBP12 were printed as negative controls.[21] We probed the arrays with purified His-tag fusions of HDAC2, HDAC3/NCoR2 peptide complex (HDAC3/NCoR2), and HDAC8 (we have determined that we are able to assess the biochemical activity of these zinc-dependent enzymes accurately). Arrays were then incubated with an Alexa-647 labeled anti-His antibody to detect HDAC binding.

Figure 2.

Small molecules tested on microarrays, in biochemical activity assays, and SPR assays.

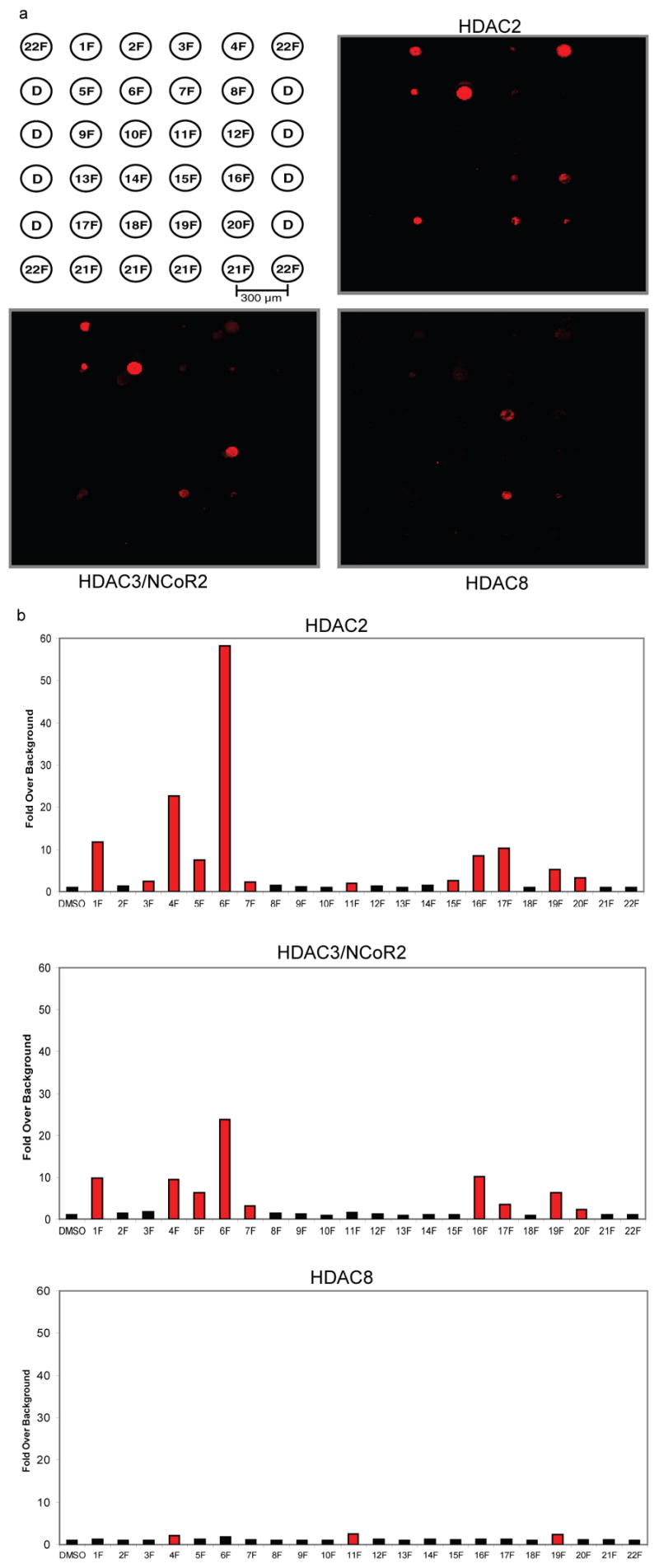

Fluorescence imaging revealed nearly identical profiles for HDAC2 and HDAC3/NCoR2, while HDAC8 displayed significant differences (Figure 3). Fluorescence intensity at 635 nm was measured for each printed compound feature and averaged over at least thirty replicates. Compounds displaying greater than two-fold signal above background (established using DMSO controls) were classified as positives (Figure 3). Compound 1F, a fluorous SAHA analogue, displayed almost ten-fold signal over background with HDAC3/NCoR2 and twelve fold over background with HDAC2. The low-potency free acid and methyl ester analogues of SAHA (2F and 3F) showed significantly lower signal in these profiles. Eight other compounds in these two profiles also displayed fluorescence above the two-fold threshold. Free SAHA was also used in a competition assay with HDAC3/NCoR2, which markedly changed the array profile (Supplementary Figure 1). SAHA is known to be a weak inhibitor of HDAC8, correlating with the observed weak signal of 1F in the profile. 11F is among the three compounds that showed significant signal over background in the HDAC8 profile.

Figure 3.

SMM data for HDAC2, HDAC3/NCoR2, and HDAC8. (a) The arrays were probed with protein followed by an Alexa 647-labeled anti-pentaHis antibody. (b) The histograms represent fold signal intensities over background established using features containing DMSO only (D in array key). Values are averages of at least thirty replicates. Red bars indicate intensities greater than two fold over background and classify as positives.

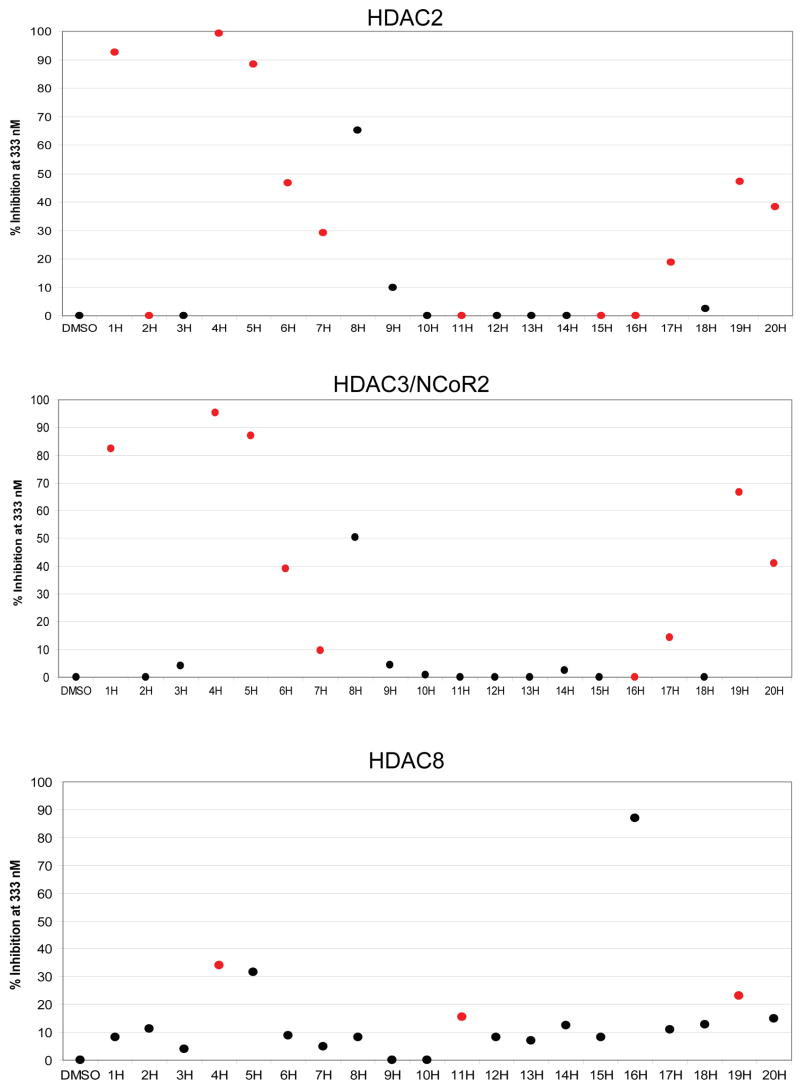

Non-fluorous analogues of each compound (compounds 1H–20H) were then assessed for enzymatic inhibition using an established biochemical activity assay (Figure 4).[35] Ten compounds for HDAC2 and nine compounds for HDAC3/NCoR2 demonstrated 10% inhibition or greater at 333 nM. As anticipated, only compounds with metal chelating elements such as hydroxamates and ortho-hydroxy anilides proved to be effective inhibitors of these enzymes. Results from biochemical activity assays and SMM assays were congruent, with eight of ten inhibitors (80%) for HDAC2 and eight of nine (89%) for HDAC3/NCoR2 also classifying as positives on the SMMs. Compound 16H, which demonstrated no inhibitory activity at 333 nM but whose analogue 16F classified as a positive, showed considerable inhibitory activity at 3.33 μM (data not shown). For HDAC8, only four compounds showed > 20% inhibition, with six weaker inhibitors falling between 10–20% inhibition. Unexpectedly, three of these weaker inhibitors were methyl ester analogues. Fifty percent of the strongest inhibitors (2/4) of HDAC8 also classified as positives on the SMMs, showing good agreement between the data sets.

Figure 4.

Biochemical activity assay data for HDAC2, HDAC3/NCoR2 complex, and HDAC8. Elements highlighted in red mark compounds classified as positives on SMMs.

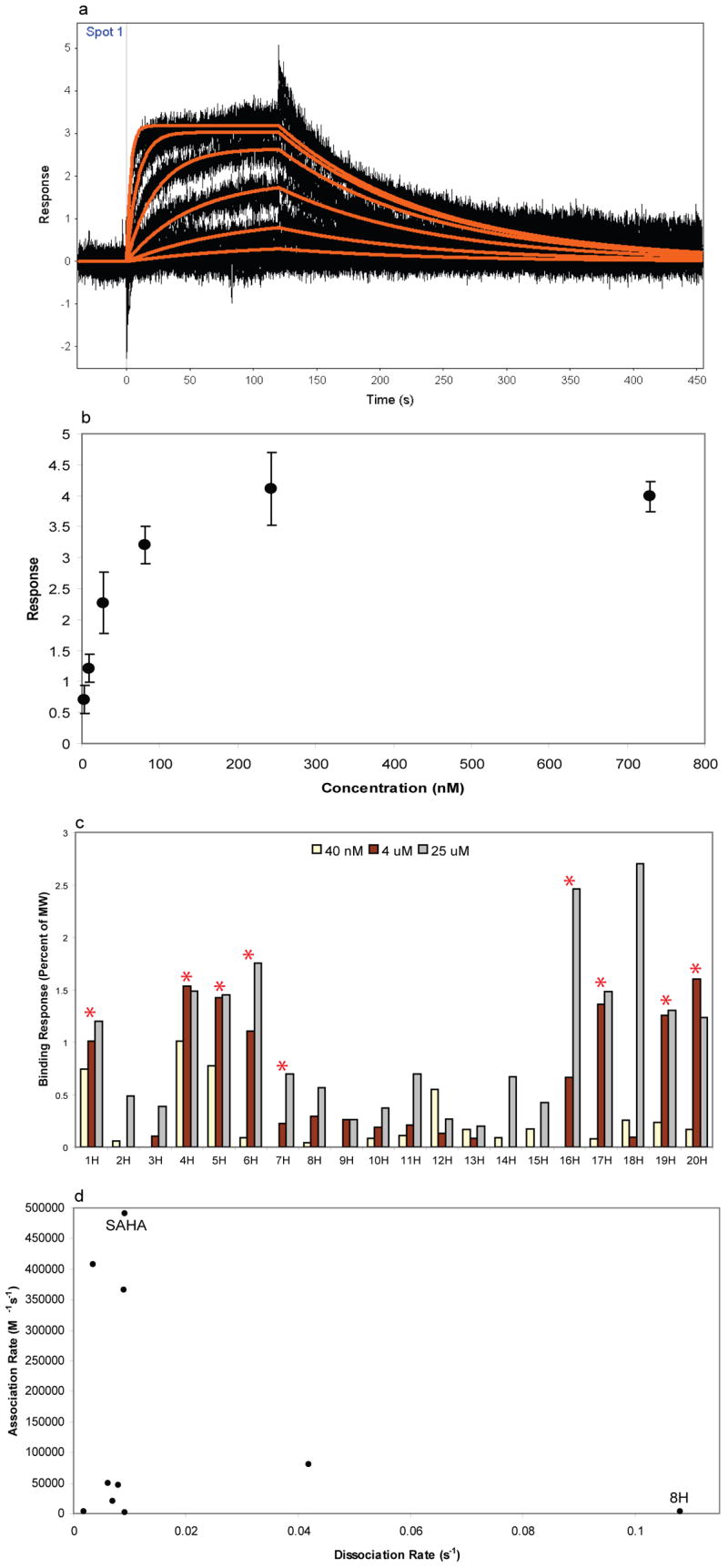

For a few compounds, data derived from microarray and biochemical activity assays for each of the HDACs did not correlate well. To account for these differences, SPR experiments were conducted with HDAC3/NCoR2 to examine the thermodynamic and kinetic binding behaviour of these compounds (Figure 5). SAHA was first rigorously characterized with HDAC3/NCoR2 to establish that the enzyme was competent for binding while displayed on the surface (Figure 5a,b). The empirically determined dissociation constant of 22 nM correlates with previously published IC50 values, providing confidence in the assay.[6]

Figure 5.

Compounds 1H–20H were tested for binding to HDAC3/NCoR2 using SPR. (a) SAHA was characterized (n=3) by measuring binding in a dilution series (3 nM to 729 nM). Thermodynamic and kinetic analyses of these curves yielded binding constants. Kinetic kon = 49 × 105 M−1 s−1, koff = 9.18 × 10−3 s−1, KD = 22 nM. (b) Plot of concentration versus response from SAHA dilution series used to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant. (c) Plot showing compound affinities at three concentrations. Red asterisks indicate compounds scored as positives in the SMM experiments. (d) Plot of kon versus koff for compounds with measurable kinetics from the SPR ranking assay.

The remaining 19 compounds were then evaluated at three different concentrations to rank their affinities and binding kinetics. The non-fluorous analogues corresponding to positives in the SMM experiments displayed significant binding in an SPR-based ranking assay (Figure 5c).[32–33] Compound 8H displayed 50% enzymatic inhibition yet its fluorous analogue did not classify as a positive. We note that 8H also had the fastest relative dissociation rate of the compounds tested (Figure 5d). Discrepancies between the different data sets may be explained by an inability of the microarrays to identify enzyme binders with relatively fast dissociation rates.

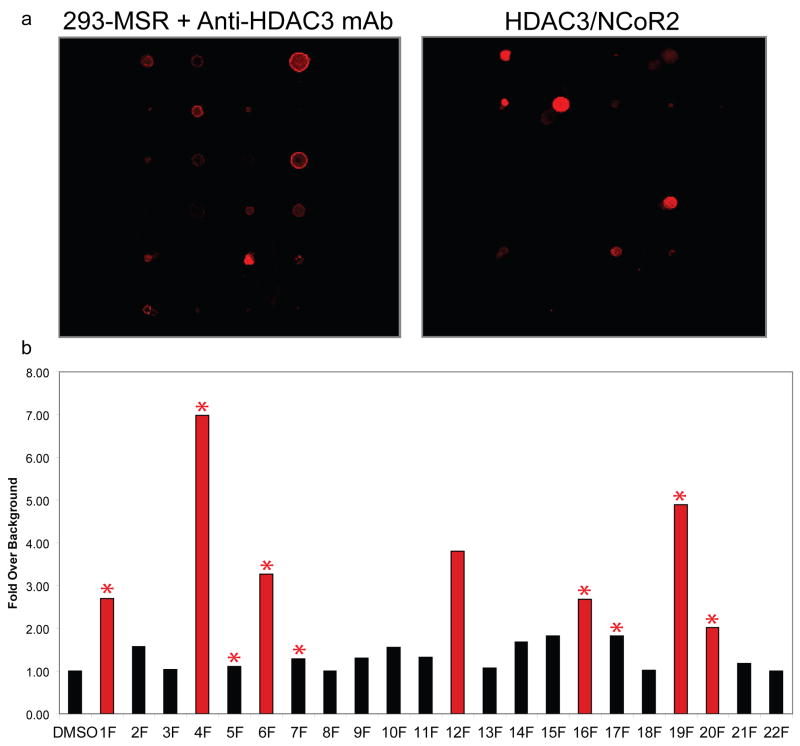

Previous studies have demonstrated that small-molecule microarrays can be used effectively with whole-cell lysates.[21] To test if fluorous microarrays can be used to detect native HDACs, arrays were incubated with whole-cell lysates from 293-MSR cells. Since HDAC3 is present in 293-MSR cells,[36] arrays were probed with mouse monoclonal anti-HDAC3 antibody mixed with Alexa-647 labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Figure 6). Six of the seven positives on these arrays also classified as positives with purified HDAC3/NCoR2, showing good agreement.

Figure 6.

Small-molecule microarray data for 293-MSR cell lysate. (a) Images of arrays treated with lysate and purified HDAC3/NCoR2. (b) Histogram of fold signal intensities over background for lysate treated arrays. Red bars indicate positives and astericks indicate compounds that were positives with purified HDAC3/NCoR2.

In conclusion, there is a strong correlation between 1) small molecules that bind HDACs identified from fluorous-based SMMs 2) inhibitors identified using biochemical activity assays and 3) binders identified from SPR assays. Fluorous-based SMMs therefore offer a viable method for discovering novel HDAC inhibitors in the future. Profiles generated from these arrays against different HDAC homologs may aid in the discovery of selective inhibitors, which is a particularly important challenge in modern chromatin research.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Footnotes

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kara Herlihy, Dr. Ralph Mazitschek, Dr. Carlos Tassa, Jason Fuller, Dr. Steve Haggarty, Dr. Jianping Cui, Dr. Letian Kuai, and Dr. Marvin Yu, Dr. Philip Yeske (Fluorous Technologies) for reagents or comments. Worked described herein has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute’s Initiative for Chemical Genetics, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Service, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government

References

- 1.Kouzarides T. Cell. 2007;128:693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. Cell. 2007;128:669. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB. Biochem J. 2003;370:737. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Science. 1996;272:408. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones PA, Baylin SB. Cell. 2007;128:683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vannini A, Volpari C, Filocamo G, Casavola EC, Brunetti M, Renzoni D, Chakravarty P, Paolini C, De Francesco R, Gallinari P, Steinkuhler C, Di Marco S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404603101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Chem Biol. 2002;9:3. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, Smith DL, Zhou X, Rosa E, Sathasivam K, Ghazi-Noori S, Mahal A, Lowden PA, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lewis CM, Marks PA, Bates GP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks PA, Jiang X. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:549. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.4.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks PA, Richon VM, Kelly WK, Chiao JH, Miller T. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;259:269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly WK, Richon VM, O’Connor O, Curley T, MacGregor-Curtelli B, Tong W, Klang M, Schwartz L, Richardson S, Rosa E, Drobnjak M, Cordon-Cordo C, Chiao JH, Rifkind R, Marks PA, Scher H. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krug LM, Curley T, Schwartz L, Richardson S, Marks P, Chiao J, Kelly WK. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:257. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Manero G, Issa JP. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:635. doi: 10.1080/07357900500283119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong JC, Hong R, Schreiber SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5586. doi: 10.1021/ja0341440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran AD, Marmo TP, Salam AA, Che S, Finkelstein E, Kabarriti R, Xenias HS, Mazitschek R, Hubbert C, Kawaguchi Y, Sheetz MP, Yao TP, Bulinski JC. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1469. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santander VS, Bisig CG, Purro SA, Casale CH, Arce CA, Barra HS. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;291:167. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hideshima T, Bradner JE, Wong J, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Schreiber SL, Anderson KC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503221102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haggarty SJ, Koeller KM, Wong JC, Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430973100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabrero JR, Serrador JM, Barreiro O, Mittelbrunn M, Naranjo-Suarez S, Martin-Cofreces N, Vicente-Manzanares M, Mazitschek R, Bradner JE, Avila J, Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Sanchez-Madrid F. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3435. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffner JL, Clemons PA, Koehler AN. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:74. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradner JE, McPherson OM, Mazitschek R, Barnes-Seeman D, Shen JP, Dhaliwal J, Stevenson KE, Duffner JL, Park SB, Neuberg DS, Nghiem P, Schreiber SL, Koehler AN. Chem Biol. 2006;13:493. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanoh N, Kyo M, Inamori K, Ando A, Asami A, Nakao A, Osada H. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2226. doi: 10.1021/ac051777j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohn M, Wacker R, Peters C, Schroder H, Soulere L, Breinbauer R, Niemeyer CM, Waldmann H. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:5830. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee MR, Shin I. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:2881. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uttamchandani M, Walsh DP, Yao SQ, Chang YT. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:4. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko KS, Jaipuri FA, Pohl NL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13162. doi: 10.1021/ja054811k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curran DP, Zhang Q, Richard C, Lu H, Gudipati V, Wilcox CS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9561. doi: 10.1021/ja061801q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2004;7:784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang W. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2007;10:219. doi: 10.2174/138620707780126697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Lu Y. J Comb Chem. 2006;8:890. doi: 10.1021/cc0601130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Lu Y, Nagashima T. J Comb Chem. 2005;7:893. doi: 10.1021/cc050061z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myszka DG. Anal Biochem. 2004;329:316. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber W. J Mol Recognit. 2005;18:273. doi: 10.1002/jmr.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sternson SM, Wong JC, Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Org Lett. 2001;3:4239. doi: 10.1021/ol016915f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz BE, Misialek S, Wu J, Tang J, Conn MT, Tahilramani R, Wong L. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11083. doi: 10.1021/bi0494471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emiliani S, Fischle W, Van Lint C, Al-Abed Y, Verdin E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.