In living cells, enzyme activity and function are tightly regulated at multiple levels through information transfer processes programmed by evolution to respond appropriately to patterns of extracellular stimuli.[1] By contrast, methods for controlling enzyme activity in vitro are typically non-informational[2] and hence not readily amenable to programming.[3] We report a general chemical encoding strategy for fashioning natural enzymes into informational and thus programmable complexes that, along with a range of programming options, can be used to modulate enzyme activity in vitro according to user-defined parameters and inputs. The approach converts an enzyme and its inhibitor into an intrasterically inactivated enzyme complex subject to DNA-directed allosteric activation.[4] An enzyme programmed in this fashion can utilize DNA inputs to selectively and reversibly turn catalytic activity on or off generating what constitutes temporally dependent output signals, read as the amounts or rates of product formed. Moreover, DNA-encoded intrasterically regulated enzymes can be readily programmed to execute specific tasks as highlighted by systems capable of performing AND, OR, and NOR logic operations and operating as sensitive PCR-independent gene diagnostic probes. Programmable enzymes are expected to impact a range of applications including molecular computation, construction of in vitro biosynthetic networks, and in biomedical settings such as diagnostics and enzyme therapeutics.

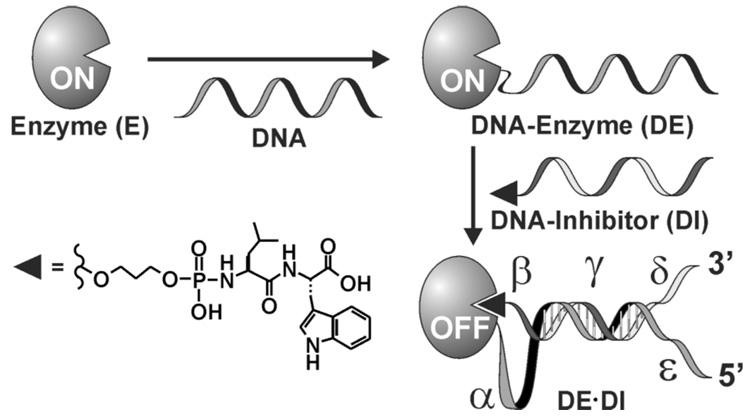

The design rationale for DNA encoding of enzyme activity is governed by the principles of intramolecularity.[5] The approach utilizes two basic components; an enzyme and its inhibitor each encoded with ss-DNA tags, herein referred to as DNA-enzyme (DE) and DNA-inhibitor (DI) modules, to direct the formation of noncovalent DE•DI complexes with desired architectural and functional features (Figure 1). Following DNA-directed DI to DE binding, the enzyme falls rapidly into an intrasterically deactivated state as a result of the high effective concentration of the inhibitor in the DE•DI complex (Figure 2a). The γ- and ε-segments on DE are used to specify the position, the architectural features, and in part, the strength of DE•DI duplex formation. To reactivate the enzyme, it is necessary to displace the inhibitor from the enzyme active site. Two distinct isothermal methods of enzyme reactivation can be employed; either via a mechanical process triggered by the conformational changes that result from rigid DNA duplex formation upon binding of an input DNA strand to the designated allosteric site (α-loop) on DE•DI complexes (Figure 2b), or by competing off the DI from DE•DI complexes with an invading ss-DNA input programmed to bind to the γ-site to regenerate the active DE module (aided by toeholds at the β-insert or δ-overhang segments) (Figure 2c). It should also be noted that either method enables the extent and rates of enzyme reactivation to be modulated by the nature of the applied DNA inputs (vide infra).

Figure 1.

Formation of an intrasterically inactivated DE•DI enzyme complex via directed noncovalent assembly of DNA-tagged enzyme (DE) and inhibitor (DI) modules. The architectural and functional features of DE•DI can be pre-programmed by appropriate encoding of various DNA segments indicated (α-ε).

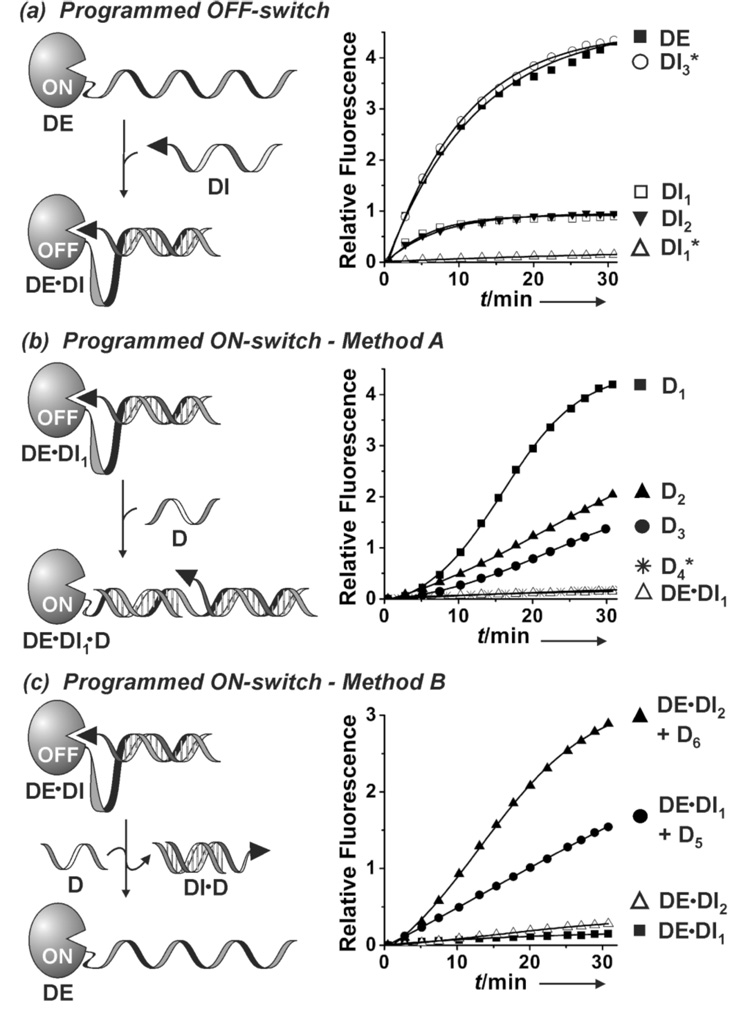

Figure 2.

Programmed enzyme inactivation and reactivation (OFF-and ON switches). Conditions: DE (2 nM), DI (50 nM), D (50 nM), in Tris/HCl (20 mM, pH 7.4), MgCl2 (50 mM), room temperature. Reaction components were mixed at t=0 in the presence of enzyme substrate (80 µM) unless indicated with an asterisk in which the components were incubated for 1 h prior to substrate addition. Product formation (catalytic endolytic cleavage of the peptide substrate) was monitored by a fluorescence plate reader (λex = 365 nm, λem = 460 nm).

DE: CGTTTCATAGCAGCGCCAGATGCTGCGCCCATAGTGCTTCCTGC—Enzyme

DE2: CGTTTCATAGCAGCGCCATGCGCCCATAGTGCTTCCTG—Enzyme

DI1: Inhibitor-GGTGGCGCTGCTATGAAACG

DI2: Inhibitor-AAGCACTATGGGCATCTGTGACTAGC

DI3: Inhibitor-GTATCTTATCTGTATTCTTA

D1: GCAGGAAGCACTATGGGCGCAGCATC

D2: GCAGGAAGCACTATGGGCGCAG

D3: GCAGGAAGCACTATGGGCGC

D4: GTATCTTATCTGTATTCTTAGTATCT

D5: CGTTTCATAGCAGCGCCACC

D6: GCTAGTCACAGATGCCCATAGTGCTT

D7: CAGGAAGCAC

D8: TATGGGCGCA

Substrate: DABCYL-βAla-Ala-Gly-Leu-Ala-βAla-EDANS

We demonstrate the utility of the enzyme encoding approach in the context of a cereus neutral protease mutant (CNPE151C). The zinc metalloprotease was tagged site-specifically via a disulfide bond, at its engineered surface exposed cysteine residue, with a 3’-thiol modified DNA sequence to give the DE module. The DI modules (DI1, DI2, and DI3) were synthesized as ss-DNA sequences modified at the 5’-termini with a phosphoramidate-based enzyme inhibitor.[4b] The enzymatic cleavage of a fluorogenic peptide substrate was used as the temporally dependent output signal. In the following discussions, DI1–3 and unmodified ss-DNA (D1–8) are considered system inputs where DI inputs are designed to turn off the enzyme and D inputs to restore enzymatic activity (see supporting information for details regarding the synthesis, purification, and characterization of molecular components employed in this study).

The OFF-switch was demonstrated by mixing the DE with DI1 or DI2 to generate the complexes DE•DI1 (α= 26, β= 2, γ= 18, δ = 0, ε= 0) and DE•DI2 (α= 5, β= 0, γ = 13, δ = 13, ε = 26), respectively (Figure 2a). In both cases, addition of DE to solutions of DI1, or DI2 resulted in rapid (<10 min) shutdown of product formation. Similarly, incubation of DE with DI prior to the addition of the enzyme substrate also resulted in essentially inactive enzyme complexes (Figure 2a). Furthermore, treatment of DE with DI3 (a DI sequence that is non-complementary to DE) under similar reaction conditions did not result in any appreciable diminution of enzyme activity underscoring the requirement for sequence-specific DNA hybridization and intramolecularity in affording intrasterically inhibited enzyme complexes.

We have employed two orthogonal DNA-directed processes to effect programmed enzyme reactivation (ON-switch). The first is based on the built-in allosteric activation feature of the DE•DI complex that can be triggered by sequence-specific binding of a ss-DNA input (D) to a designated target site on the α-loop segment to furnish the enzymatically active DE•DI•D ternary complex (Figure 2b). The allosteric trigger was designed to operate based on the following thermodynamic and structural considerations. Upon formation of a thermodynamically favorable DNA duplex structure, the α-loop conformation is drastically altered creating a mechanical tension that drives the displacement of the inhibitor from the enzyme active site. The effectiveness of the allosteric activation process is evidenced by the rapid onset of enzyme activity upon addition of D1, a 26-mer ss-DNA sequence complementary to the α-loop, to a solution of the inactive DE•DI1 enzyme complex (Figure 2b). On the other hand, addition of D4, a 26-mer ss-DNA sequence that is not complementary to the α-loop, to a similar solution failed to activate the enzyme illustrating the sequence-specificity of the ON-switch mechanism. Thermodynamic considerations indicate that the ratio of the active DE•DI•D enzyme versus the inactive DE•DI present at equilibrium can be influenced by several factors including the free energy of input binding (hybridization) to its α-loop target site. Accordingly, since the input and its α-loop binding site sequences are defined by the user, the enzyme encoding method offers the option of rationally modulating the enzyme reactivation efficiency to a desired level simply by the appropriate programming of ON-switch thermodynamics. The effect of input hybridization free energy on DE•DI1 activation can be readily surmised by comparing the observed rates of product formation in response to D1 (26-mer), D2 (22-mer), or D3 (20-mer) (Figure 2b). The decreasing order of enzyme activation parallels the predicted decrease in the hybridization free energies of the progressively shorter input strands (D1 > D2 > D3) for binding to the allosteric α-loop segment of DE•DI1 (data not shown). The ability to program desired system thermodynamics is an important feature enabling rational design of multi-input enzyme complexes capable of reversible OFF-ON switching and logic operations (vide infra).

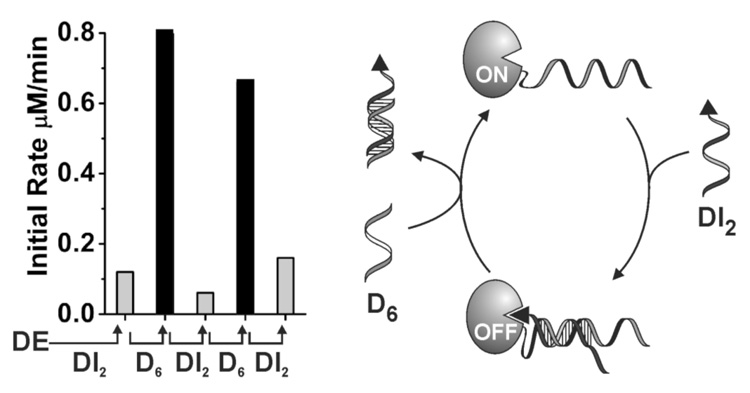

The second method of programmed enzyme reactivation is based on competitive binding of input DNA to, and displacement of, the DI module from DE•DI.[6] The effectiveness of this method is supported by the rapid onset of enzymatic activity upon addition of D5 (a 20 base long ss-DNA input complementary to DI1) to DE•DI1, or D6 (a 26 base long ss-DNA input complementary to DI2) to DE•DI2 (Figure 2c). Programming a shorter γ-region on DE•DI2 (13 base pairs) versus DE•DI1 (18 base pairs) and the longer encoded ss-DNA portion on DI2 (δ = 13) versus DI1 (β = 2) in their respective DE•DI complexes makes duplex formation between D6 and DI2 (26 base pairs) energetically more favorable than binding of D5 to DI1 (20 base pairs) and consequently results in a faster observed rate of product formation when D6 is mixed with DE•DI2, than when D5 is added to a solution of DE•DI1 complex. This method of enzyme reactivation can also be used to cycle the enzyme between ON- and OFF-states as exemplified in a study where the inputs DI2 and D6 were added successively to a solution of DE (Figure 3 and SI Figure 2S–3S).

Figure 3.

ON-OFF switch cycles via successive additions of DI2 and D6 (50 nM each) to DE (2 nM) in Tris/HCl (20 mM, pH 7.4), MgCl2 (50 mM), in the presence of substrate (80 µM) at room temperature.

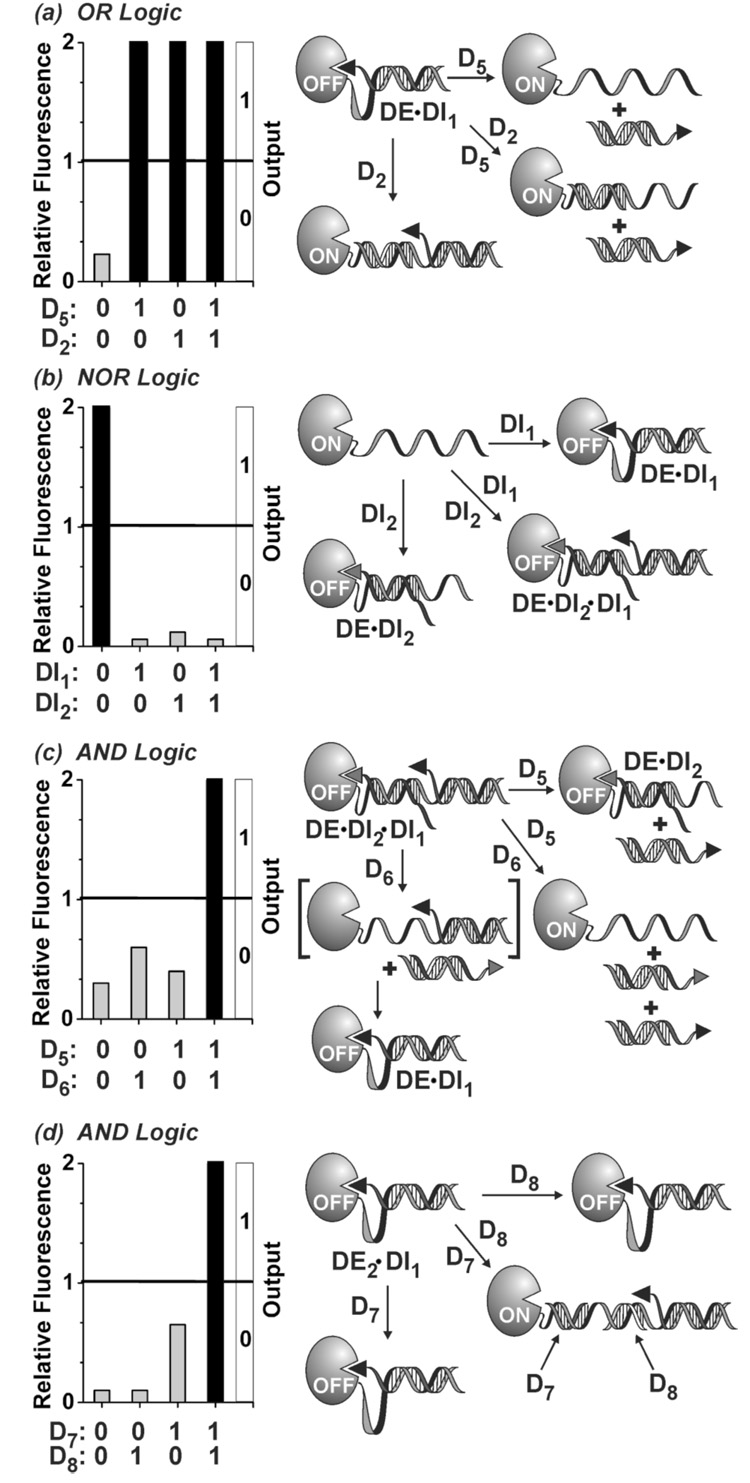

The DNA encoding method affords a number of options for programming enzymes to perform complex tasks. This is illustrated by enzyme constructs capable of performing AND, OR, and NOR logic operations.[2m,7–10] The logic gates, each defined by its corresponding truth table, were derived from DE using different encoded enzyme architectures (Figure 4). We have used threshold analysis to assign outputs (0, 1), but implicit in the use of enzymes in molecular computation is the temporal dependence of signal evolution (product formation) that can be indispensable in fuzzy logic operations and complex circuit designs.[1a] The OR gate was designed based on the binary DE•DI1 architecture to give a true output when either one or both inputs are true (Figure 4a and SI Figure 4S). Utilizing both ON-switch mechanisms, the OR gate was programmed for allosteric activation by D2 and competitive DI1 displacement by D5. Furthermore, since D2 and D5 employ non-complementary sequences, addition of either or both inputs activates the enzyme complex. The NOR gate was programmed based on the same DE but in conjunction with DI1 and DI2 as inputs (Figure 4b and SI Figure 5S). Addition of either input rapidly turns-off the enzyme by producing the corresponding intrasterically inactivated DE•DI complexes. Moreover, because DI1 and DI2 each bind to a unique and non-overlapping γ-site on DE, addition of both inputs also inactivates the enzyme via the formation of DE•DI2•DI1 ternary complex. AND logic calls for a true output only when both inputs are true. We have established the AND gate by exploiting the dual inhibitor architecture of the DE•DI2•DI1 ternary complex using D5 and D6 as inputs (Figure 4c and SI Figure 6S). The crucial feature of the DE•DI2•DI1 ternary complex is that displacement of either DI1 or DI2 inhibitor strands, by the sequence-specific competitive binding action of D5 or D6, respectively, results in binary DE•DI2 or DE•DI1 complexes that remain in the OFF-state as the result of intrasteric inhibition. Enzyme reactivation takes place only when both DI1 and DI2 strands are displaced from DE•DI2•DI1 complex by the combined action of D5 and D6 (SI Figure 6S). The AND logic could also be executed using a gate architecture that utilizes cooperative binding of two non-overlapping input strands (D7 and D8) to the 20-mer allosteric α-loop of DE2•DI1 enzyme complex defined by the parameters α = 20, β = 2, γ = 18, δ = 0, and ε = 0 (Figure 4d and SI Figure 7S). It should be noted that as a result of the built-in signal amplification (enzyme turnover), the DNA-encoded intrasterically regulated enzymes have considerable potential in gene diagnostic applications especially where highly sensitive, rapid, and PCR-independent detection of label-free nucleic acid sequences are desired (see SI Figure 8S for the detection of 5 fmol or 100 amol of a HIV target sequence in less than 20 or 100 minutes, respectively). In this regard, the logic gates offer an expanded capacity where one or more genetic markers, in combination (AND logic) or separately (OR logic), are required to identify a given disorder or disease state.

Figure 4.

Programming enzymes to perform OR, NOR, and AND logic operations. Logic gate architectures: (a) OR gate (DE•DI1); (b) NOR gate (DE); (c) AND gate (DE•DI2•DI1); and (d) AND gate (DE2•DI1). General conditions: DE and DE2 (2 nM), DI1 and DI2 (50 nM), D2, D5, and D6 (50 nM), D7, and D8 (10 nM), substrate (80 µM) in Tris/HCl (20 mM, pH 7.4), MgCl2 (50 mM), room temp. Logic gates were prepared by incubating the appropriate DE and DI strands for 30 min prior to input addition. Substrate was added simultaneously with input strands, except for the NOR gate which was incubated with inputs for 30 min prior to substrate addition. See SI Figures 4S–7S for full time course data and control studies.

The studies reported here establish a basic design concept for fashioning natural enzymes into informational and thus programmable complexes that, along with a range of programming options, can be used to modulate enzyme activity according to user-defined parameters and inputs. Although DNA seems to be an ideal choice for enzyme encoding, it is reasonable to expect that other types of informational polymers including RNA and unnatural nucleic acid constructs could also be effectively employed. We suggest that similar design tactics might be useful in devising ligand-dependent intrasterically regulated enzymes by exploiting selective and thermodynamically suitable molecular recognition events. Consequently, a large variety of cellular receptor-ligand interactions could potentially be used to devise novel enzyme therapeutics in which enzyme activation can be programmed to take place in response to a particular, or a set of, intra- or extra-cellular markers.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Footnotes

We thank NIGMS (GM-67170) for financial support, the American Australian Association and Dow Chemical Company for a postdoctoral fellowship to NCG, and our colleagues J. M. Picuri and A. Loutchnikov for their assistance and helpful suggestions.

Contributor Information

Nathan C. Gianneschi, Dr. N. C. Gianneschi, Prof. Dr. M. R. Ghadiri, Departments of Chemistry and Molecular Biology and the, Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA, 92037 (USA), Fax: (+1) 858-784-2798

M. Reza Ghadiri, Dr. N. C. Gianneschi, Prof. Dr. M. R. Ghadiri, Departments of Chemistry and Molecular Biology and the, Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA, 92037 (USA), Fax: (+1) 858-784-2798, E-mail: ghadiri@scripps.edu.

References

- 1.a) Arkin A, Ross J. Biophys. J. 1994;67:560–578. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80516-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bray D. Nature. 1995;376:307–312. doi: 10.1038/376307a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Bieth J, Vratsanos SM, Wassermann N, Erlanger BF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1969;64:1103–1106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.3.1103. M. A. Wainberg, B. F. Erlanger, Biochemistry 1971, 10, 3816–3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Berezin IV, Varfolomeev SD, Klibanov AM, Martinek K. FEBS Lett. 1974;39:329–331. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(74)80142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Corey DR, Schultz PG. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:3666–3669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Westmark PR, Kelly JP, Smith BD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3416–3419. [Google Scholar]; e) Stayton PS, Shimoboji T, Long C, Chilkoti A, Chen G, Harris JM, Hoffman AS. Nature. 1995;378:472–474. doi: 10.1038/378472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Liu D, Karanicolas J, Yu C, Zhang Z, Woolley GA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1997;7:2677–2680. [Google Scholar]; g) Doi N, Yanagawa H. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:305–307. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00732-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:11241–11246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Posey KL, Gimble FS. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2184–2190. doi: 10.1021/bi015944v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Liu H, Schmidt JJ, Bachand GD, Rizk SS, Looger LL, Hellinga HW, Montemagno CD. Nat. Mater. 2002;1:173–177. doi: 10.1038/nmat761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Feliu JX, Ferrer-Miralles N, Blanco E, Cazorla D, Sobrino F, Villaverde A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Prot. Struct. Mol. Enzy. 2002;1596:212–224. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(02)00226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Looger LL, Dwyer MA, Smith JJ, Hellinga HW. Nature. 2003;423:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Dueber JE, Yeh BJ, Chak K, Lim WA. Science. 2003;301:1904–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1085945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n) Guntas G, Ostermeier M. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Bose M, Groff D, Xie J, Brustad E, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:388–389. doi: 10.1021/ja055467u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Corey DR, Schultz PG. Science. 1987;238:1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.3685986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Uchiyama Y, Inoue H, Ohtsuka E, Nakai C, Kanaya S, Ueno Y, Ikehara M. Bioconjugate Chem. 1994;5:327–332. doi: 10.1021/bc00028a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stojanovic MN, De Prada P, Landry DW. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:411–415. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010601)2:6<411::AID-CBIC411>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dittmer WU, Reuter A, Simmel FC. Angew. Chem. 2004;116:3634–3637. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353537. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3550–3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Simon P, Dueymes C, Fontecave M, Decout J-L. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:2824–2827. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461145. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2764–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Choi B, Zocchi G, Wu Y, Chan S, Perry LJ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95:078102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.078102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Pavlov V, Shlyahovsky B, Willner I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6522–6523. doi: 10.1021/ja050678k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Kobe B, Kemp BE. Nature. 1999;402:373–376. doi: 10.1038/46478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Saghatelian A, Guckian KM, Thayer DA, Ghadiri MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:344–345. doi: 10.1021/ja027885u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page MI, Jencks WP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1971;68:1678–1683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luan G, Guo Q, Liang J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e5/1–e5/9. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews of organic and supramolecular logic gates, see: Balzani V, Credi A, Raymo FM, Stoddart JF. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:3484–3530. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001002)39:19<3348::aid-anie3348>3.0.co;2-x. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3348–3391.Raymo FM. Adv. Mater. 2002;14:401–414.Balzani V, Credi A, Venturi M. ChemPhysChem. 2003;4:49–59. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200390007.de Silva AP, McClenaghan ND. Chem.—Eur. J. 2004;10:574–586. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305054.

- 8.For examples of nucleic acid-based programming, logic gates and molecular computation, see: Adleman LM. Science. 1994;266:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7973651.Lipton RJ. Science. 1995;268:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.7725098.Guarnieri F, Fliss M, Bancroft C. Science. 1996;273:220–223. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.220.Ouyang Q, Kaplan PD, Liu S, Libchaber A. Science. 1997;278:446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.446.Cox JC, Cohen DS, Ellington AD. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01312-8.Storhoff JJ, Mirkin CA. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:1849–1862. doi: 10.1021/cr970071p.Faulhammer D, Cukras AR, Lipton RJ, Landweber LF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:1385–1389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1385.Mao C, LaBean TH, Reif JH, Seeman NC. Nature. 2000;407:493–496. doi: 10.1038/35035038.Stojanovic MN, Mitchell TE, Stefanovic D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3555–3561. doi: 10.1021/ja016756v.Hartig JS, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Gruene I, Yan A, Ellington AD, Famulok M. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:717–722. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-717.Benenson Y, Adar R, Paz-Elizur T, Livneh Z, Shapiro E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:2191–2196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535624100.Stojanovic MN, Stefanovic D. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1069–1074. doi: 10.1038/nbt862.Saghatelian A, Volcker NH, Guckian KM, Lin VS, Ghadiri MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:346–347. doi: 10.1021/ja029009m.Okamoto A, Tanaka K, Saito I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9458–9463. doi: 10.1021/ja047628k.Benenson Y, Gil B, Ben-Dor U, Adar R, Shapiro E. Nature. 2004;429:423–429. doi: 10.1038/nature02551.Rothemund PWK, Ekani-Nkodo A, Papadakis N, Kumar A, Fygenson DK, Winfree E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16344–16352. doi: 10.1021/ja044319l.Penchovsky R, Breaker RR. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1424–1433. doi: 10.1038/nbt1155.Stojanovic MN, Semova S, Kolpashchikov D, Macdonald J, Morgan C, Stefanovic D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6914–6915. doi: 10.1021/ja043003a.Seeman NC. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.007.Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E. Science. 2006;314:1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.1132493.

- 9.For peptide and protein-based logic operations, see: Zauner K-P, Conrad M. Biotechnol. Prog. 2001;17:553–559. doi: 10.1021/bp010004n.Sivan S, Tuchman S, Lotan N. BioSystems. 2003;70:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s0303-2647(03)00039-x.Radley TL, Markowska AI, Bettinger BT, Ha J-H, Loh SN. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;332:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00925-2.Ashkenasy G, Ghadiri MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11140–11141. doi: 10.1021/ja046745c.Baron R, Lioubashevski O, Katz E, Niazov T, Willner I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:989–991. doi: 10.1039/b518205k.Baron R, Lioubashevski O, Katz E, Niazov T, Willner I. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:1602–1606. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503314. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1572–1576.

- 10.For logic operations based on engineering biochemical and cell signalling pathways, see: Hjelmfelt A, Weinberger ED, Ross J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:10983–10987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.10983.Elowitz MB, Leibier S. Nature. 2000;403:335–337. doi: 10.1038/35002125.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Nature. 2000;403:339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131.Guet CC, Elowitz MB, Hsing W, Leibler S. Science. 2002;296:1466–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1067407.Hasty J, McMillen D, Collins JJ. Nature. 2002;420:224–230. doi: 10.1038/nature01257.Yokobayashi Y, Weiss R, Arnold FH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:16587–16591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252535999.Atkinson MR, Savageau MA, Myers JT, Ninfa AJ. Cell. 2003;113:597–607. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00346-5.Tyson JJ, Chen KC, Novak B. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00017-6.Dueber JE, Yeh BJ, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. Curr.Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.004.Chen M-T, Weiss R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1551–1555. doi: 10.1038/nbt1162.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.