There is considerable interest in the use of bioorthogonal covalent chemistry such as “click” chemistries to label small molecules located on live or fixed cells.[1] Such labeling has been used for the visualization of glycans, activity based protein profiling, site-specific tagging of proteins, detection of DNA and RNA synthesis, revealing the fate of small molecules in plants, and detection of post-translational modification in proteins.[2-4] Most reported applications rely on either the copper catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition, which is limited to in vitro application due to the cytotoxicity of copper, or the elegant strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition, which permits live cell and in vivo application use but is hindered by relatively slow kinetics and often difficult synthesis of cyclooctyne derivatives.[4-5] New bioorthogonal reactions that do not require catalyst and show rapid kinetics are therefore of interest for different molecular imaging applications at the cellular level. In this report we demonstrate the use of inverse electron demand Diels-Alder cycloaddition between a serum stable 1,2,4,5 tetrazine and a highly strained trans-cyclooctene to covalently label live cells. This chemistry has been applied to the pretargeted labeling of Cetuximab (Erbitux) tagged epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) on A549 cancer cells. We find that the tetrazine cycloaddition to trans-cyclooctene labeled cells is fast and can be amplified by increasing the loading of dienophile on the antibody. This results in a highly sensitive targeting strategy that can be used to label proteins using nanomolar concentrations of a secondary agent for short durations of time.

Recently we and others have explored strain promoted inverse electron demand Diels-Alder cycloadditions with 1,2,4,5 tetrazines for bioconjugation.[6-7] We have previously shown that tetrazine cycloaddition to norbornene can be applied to pretargeted imaging of live breast cancer cells. However, the rate of cycloaddition between the tetrazine and norbornene was 1.6 M-1sec-1 in serum at 20°C. This rate is comparable to previously reported rates for optimized azide-cyclooctyne cycloadditions and requires micromolar concentrations to achieve sufficient labeling.[3-4] Based on previously reported rate constants, we were interested in exploring the coupling of tetrazines with more strained dienophiles.[8] Higher rate constants would allow for faster and more efficient labeling thus requiring less labeling agent and lowering background signal. Recently, Fox and coworkers reported the use of a highly strained trans-cyclooctene for bioconjugation.[6, 9] Though the rates reported were impressive, the tetrazine that yielded the fastest rate has limited stability to nucleophiles and aqueous media, with significant degradation observed after several hours. In contrast, we have reported on the use of a novel asymmetric tetrazine (1) that has been shown to be very stable in water as well as in whole serum which is a prerequisite for in vivo applications.[7] We hypothesized that tetrazine 1 would react with trans-cyclooctene significantly faster than the previously reported norbornene, and this would greatly improve the sensitivity of cell labeling via tetrazine cycloaddition. With this goal in mind, trans-cyclooctene dienophile (2) was synthesized in two steps from a commercially available cyclooctene epoxide. The trans-cyclooctene reacts readily with tetrazine 1 in greater than 95% yield forming isomeric dihydropyrazine conjugation products (Figure 1a, see supplementary information). Trans-cyclooctenol 2 can be converted to the reactive succinimidyl carbonate and the carbonate can be conjugated to amine containing biomolecules such as monoclonal antibodies by forming a carbamate linkage. In order to determine the second order rate constant for the reaction of tetrazine with trans-cyclooctene, surface arrays of trans-cyclooctene antibodies were modified with a fluorescent tetrazine probe and the fluorescence signal was monitored with time (Figure S3a). From these data, a second order rate constant of 6000±200 M-1sec-1 at 37°C (Figure S3b) was determined. This rate constant is several orders of magnitude faster than the previously reported value for the cycloaddition of tetrazine 1 with a norbornene as well as the previously reported rate constants for bioorthogonal click reactions used to label live cells covalently.[3-4, 7]

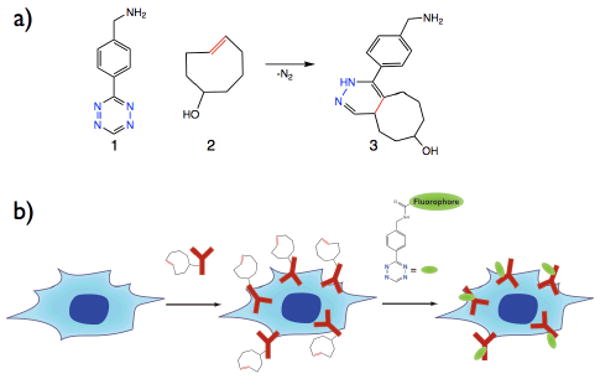

Figure 1.

a) Benzylamino-tetrazine 1 reacts with trans-cyclooctenol 2 by an inverse electron demand Diels-Alder cycloaddition. Dinitrogen is released and dihydropyrazine coupling products such as 3 are formed. b) Live cell pretargeting scheme. Cancer cells (blue), which over-express EGFR are exposed to Cetuximab/trans-cyclooctene conjugate (red). In the next step, the pre-targeted cells are labeled with tetrazine bearing a fluorophore such as VT-680 (green).

To demonstrate the utility of the tetrazine trans-cyclooctene reaction for live cell imaging, we chose to label EGFR expressed on A549 lung cancer cells using an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody (Cetuximab). The pretargeting concept is illustrated in Figure 1b. Multistep labeling of monoclonal antibodies is of interest due to the long blood half-life of antibodies, which leads to poor target to background ratios when the antibodies are directly labeled with imaging agents or cytotoxins.[10] A small molecule-based pretargeting strategy, relying on irreversible covalent chemistry, may circumvent these problems and provide a general strategy for the delivery of imaging agents and therapeutics.

For cell labeling studies, we chose to work with an anti-EGFR antibody given EGFR's central importance in cancer cell signaling,[12] as a key target for therapeutic inhibition,[13] and prior work with fluorophore labeled antibodies, which serves as a reference.[14] Commercially available Cetuximab was labeled with trans-cyclooctene succinimidyl carbonate and used for pretargeting experiments. As a cancer model, we chose to work with a GFP positive A549 lung cancer line which has shown to have upregulated levels of EGFR.[15] To label cells pretargeted with trans-cyclooctene bearing antibodies, tetrazine amine 1 was conjugated to a commercially available far red indocyanine fluorophore, Vivo-Tag 680 (VT680 purchased from VisEn Medical). The decision to work with tetrazine-fluorophore probes was based on the commercial availability of numerous amine reactive fluorophores. Furthermore, we have previously reported use of this compound and have shown that the tetrazine moiety is serum stable and reacts rapidly with strained dienophiles.[7]

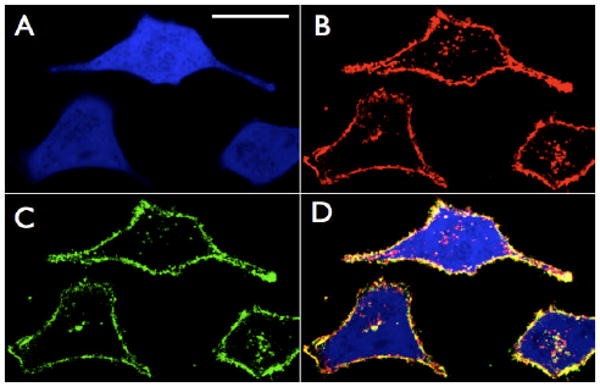

Initial pretargeting experiments used Cetuximab modified by trans-cyclooctene and additionally a single Alexafluor 555 dye (AF 555 purchased from Invitrogen) in order to determine if sequential VT680-tetrazine labeling colocalized with antibody. A549 cancer cells were first incubated with 100 nM Cetuximab transcyclooctene/AF555 for 45 minutes in serum. The cells were then washed, incubated at 37°C with 500 nM tetrazine-VT680 for 10 minutes in 100% fetal bovine serum (FBS), washed again, and immediately imaged using confocal microscopy (Figure 2). AF555 directly labeled on the antibodies was monitored in the red channel (Figure 2 panel B red). The antibody is clearly seen both on the surfaces of the cells and inside due to EGFR internalization.[16-17] Covalently bound tetrazine-VT680 could be clearly visualized in the NIR channel (Figure 2 panel C green). Merging the red and near-IR channels revealed excellent colocalization of the AF555 and VT680 signals with little background indicating that the tetrazine reaction is extremely selective. As expected, reaction occurred primarily on the surface of the cells, where EGFR concentrations are highest. A smaller amount of cell internalized, vesicle-associated NIR fluorescence was also observed, likely due to EGFR internalized after treatment with tetrazine-VT680.[16-17] Control experiments using either unlabeled Cetuximab with tetrazine-VT680 or transcyclooctene Cetuximab with unlabeled VT680 resulted in no NIR fluorescent signal (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

Confocal microscopy of Cetuximab pretargeted GFP-positive A549 lung cancer cells after tetrazine-fluorophore labeling. A) GFP channel. White scale bar in top left panel denotes 30 microns. B) Red channel: Cetuximab/trans-cyclooctene antibodies have also been directly labeled with AF555 and imaged in the rhodamine channel. Some of the antibody has been internalized as indicated by the signal inside the cells. C) Near-IR channel showing the location of bound tetrazine-VT680 probe (500 nM 10 minutes 100% FBS 37°C). D) Merge of GFP, Red, and Near-IR channels. Note the excellent colocalization of the red and near-IR channels especially at the surface of the cells. Intracellular Cetuximab, which as not reacted with tetrazine-VT680 can be clearly visualized and is likely due to Cetuximab that was internalized prior to the addition of the extracellular tetrazine-VT680 probe.

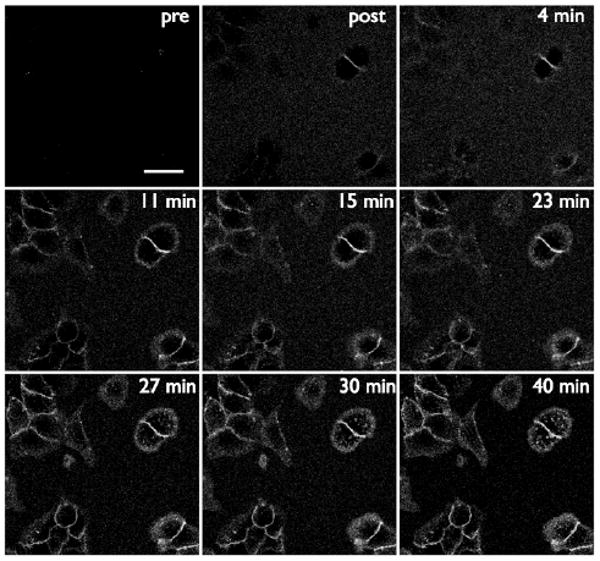

Next we tested if labeling could be observed without a washout of probe. This is relevant to applications where one is unable to perform stringent and multiple washing steps, such as intracellular labeling, experiments in which cell handling has to be minimized (rare cells or with highly specialized cells) or in vivo labeling. The concentration of the tetrazine-VT680 label was lowered to 50 nM in order to observe the covalent modification in real time. Figure 3 depicts several panels taken from continuous imaging of the tetrazine cycloaddition to pretargeted trans-cyclooctene on live cancer cells in 100% FBS containing 50 nM VT680. The tetrazine-VT680 first becomes visible as it reacts and concentrates on the surface of cells, and at later times, punctate spots within the cell are visible as tetrazine labeled Cetuximab is internalized.

Figure 3.

Real time imaging of tetrazine labeling of pretargeted A549 cells. Cells were exposed to Cetuximab trans-cyclooctene, washed, and imaged in 100% FBS using the near-IR channel (panel top left). The FBS was removed and immediately replaced with FBS containing 50 nM tetrazine-VT680 (top middle panel). Images were taken periodically over 40 minutes. The signal around the cell surfaces continues to increase as a function of time. The scale bar in the top left panel denotes 30 microns.

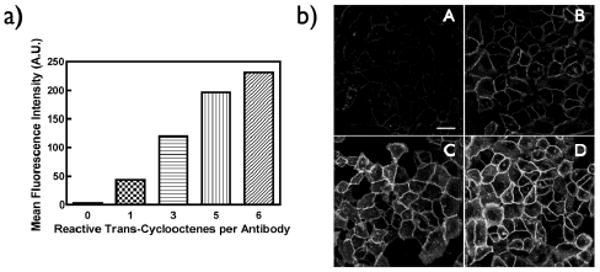

In order to improve signal to background we explored increasing the loading density of the reactive trans-cyclooctene on the targeted antibodies. A greater number of reactive sites per antibody should lead to more fluorophore per antibody after labeling, resulting in signal amplification. In order to vary the loading of transcyclooctene, Cetuximab was exposed to different molar excesses of amine reactive trans-cyclooctene. The conjugates could be modified by tetrazine-VT680 and the resulting fluorochrome absorbance was used to estimate the number of reactive trans-cyclooctenes per antibody. In this fashion Cetuximab bearing, 1, 3, 5, and 6 tetrazine VT-680 reactive trans-cyclooctenes were prepared. It should be noted that due to the large size of indocyanine dyes, the number of reacted trans-cyclooctenes for the higher loadings is likely lower than the actual number on the antibody. These transcyclooctene Cetuximab conjugates bound to EGFR expressing A549 cells with excellent stability (Figure S5).

To gain a more quantitative understanding of the tetrazine live cell fluorescent labeling, flow cytometry was employed. A549 cells were incubated with 50 nM of Cetuximab modified with either 0, 1, 3, 5, or 6 reactive trans-cyclooctenes. The tetrazine VT680 cycloaddition was carried out using 500 nM tetrazine labeling agent at 37 °C in 100% FBS. After 30 minutes, the cells were washed and the fluorescence intensity was analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 4a shows the relative VT680 signal intensity after 30 minutes for all five loadings of trans-cyclooctene. To illustrate the practical effect this amplification has on imaging of live cells, we pretargeted A549 cells with 100 nM Cetuximab conjugated to 1, 3, 5, and 6 reactive trans-cyclooctenes, then exposed the cells to 100 nM tetrazine-VT680 for 10 minutes and imaged with confocal microscopy (Figure 4b). Cells are easily visualized with the more highly loaded trans-cyclooctene conjugated Cetuximab constructs, and the signal diminishes as one reduces the amount of the dienophile on the antibody. The ability to amplify signals by loading increased amounts of small molecules on the antibody could be a strategy to increase signal to background for in vivo pretargeting schemes.

Figure 4.

a) Analysis of live cell labeling by flow cytometry. Fluorescence intensity after 30 minutes reaction with 500 nM tetrazine VT680 versus the loading of reactive transcyclooctene on the antibody. b) Confocal microscopy of A549 cells pretargeted with Cetuximab loaded with either 1 (A), 3 (B), 5 (C), or 6 (D) trans-cyclooctenes and then labeled with 100 nM tetrazine VT680 for 10 minutes. Note the increasing fluorescence signal correlates with the increasing trans-cyclooctene labeling levels of the antibody. (all cells were exposed to identical concentrations of antibody). The white scale bar in top left panel denotes 30 microns.

In conclusion, we have performed highly sensitive covalent labeling of live cancer cells using a tetrazine-based cycloaddition to a highly strained trans-cyclooctene. Given the utility of this technology, tetrazine reactions should find application in various live cell labeling techniques. With appropriate choice of a cell permeable labeling agent, this method should be readily extendable to intracellular labeling, which could facilitate tracking of tagged small molecule drugs, signalling proteins, or other cellular machinery within live cells. In addition, tetrazines and transcyclooctene unnatural amino acids may be amenable to site specific incorporation into proteins of interest and revealed in live cells. Furthermore, given the speed and sensitivity of the labeling reaction in whole serum, this reaction should be translatable to in vivo imaging applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ned Keliher for helpful advice. This research was supported in part by NIH grants U01-HL080731 and T32 − CA 79443.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.Baskin JM, Bertozzi CR. QSAR & Combinatorial Science. 2007;26:1211–1219. [Google Scholar]; Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Nature Chemical Biology. 2005;1:13–21. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0605-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Raghavan AS, Hang HC. Drug Discovery Today. 2009;14:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sadaghiani AM, Verhelst SHL, Bogyo M. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2007;11:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem. 2001;113:2056–2075. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem. 2002;114:2708–2711. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neef AB, Schultz C. Angew Chem. 2009;121:1526–1529. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1498–1500. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Salic A, Mitchison TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Speers AE, Adam GC, Cravatt BF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4686–4687. doi: 10.1021/ja034490h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Deiters A, Cropp TA, Mukherji M, Chin JW, Anderson JC, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11782–11783. doi: 10.1021/ja0370037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jao CY, Salic A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15779–15784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kaschani F, Verhelst SH, van Swieten PF, Verdoes M, Wong CS, Wang Z, Kaiser M, Overkleeft HS, Bogyo M, van der Hoorn RA. Plant J. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Martin BR, Cravatt BF. Nat Methods. 2009;6:135–138. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ning XH, Guo J, Wolfert MA, Boons GJ. Angew Chem. 2008;120:2285–2287. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2253–2255. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA, Lo A, Codelli JA, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16793–16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15046–15047. doi: 10.1021/ja044996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackman ML, Royzen M, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13518–13519. doi: 10.1021/ja8053805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devaraj NK, Weissleder R, Hilderbrand SA. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:2297–2299. doi: 10.1021/bc8004446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauer J, Heldmann DK, Hetzenegger J, Krauthan J, Sichert H, Schuster J. Eur J Org Chem. 1998:2885–2896. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royzen M, Yap GP, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3760–3761. doi: 10.1021/ja8001919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu AM, Senter PD. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1137–1146. doi: 10.1038/nbt1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin DA, Meares CF. Biotechnol Adv. 2001;19:435–450. doi: 10.1016/s0734-9750(01)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Goodwin DA, Meares CF, Watanabe N, McTigue M, Chaovapong W, Ransone CM, Renn O, Greiner DP, Kukis DL, Kronenberger SI. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5937–5946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Cardillo TM, Chang CH, McBride WJ, Rossi EA, Horak ID, Goldenberg DM. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7109s–7121s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachoo RM, Maher EA, Ligon KL, Sharpless NE, Chan SS, You MJ, Tang Y, DeFrances J, Stover E, Weissleder R, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, DePinho RA. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, Louis DN, Christiani DC, Settleman J, Haber DA. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett T, Koyama Y, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Shin IS, Jang BS, Paik CH, Urano Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6639–6648. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bogdanov AJ, Kang HW, Querol M, Pretorius PH, Yudina A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1123–1130. doi: 10.1021/bc060392k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Koyama Y, Barrett T, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Neoplasia. 2007;9:1021–1029. doi: 10.1593/neo.07787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rosenthal EL, Kulbersh BD, Duncan RD, Zhang W, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Zinn K. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1636–1641. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000232513.19873.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rosenthal EL, Kulbersh BD, King T, Chaudhuri TR, Zinn KR. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1230–1238. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachwal WJ, Bongiorno PF, Orringer MB, Whyte RI, Ethier SP, Beer DG. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:56–64. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang NS, Liu C, Emond J, Tsao MS. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1992;16:439–449. doi: 10.3109/01913129209057829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincenzi B, Schiavon G, Silletta M, Santini D, Tonini G. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel D, Lahiji A, Patel S, Franklin M, Jimenez X, Hicklin DJ, Kang X. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:3355–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.