Abstract

The human genome contains 40 voltage-gated potassium channels (KV) which are involved in diverse physiological processes ranging from repolarization of neuronal or cardiac action potentials, over regulating calcium signaling and cell volume, to driving cellular proliferation and migration. KV channels offer tremendous opportunities for the development of new drugs for cancer, autoimmune diseases and metabolic, neurological and cardiovascular disorders. This review first discusses pharmacological strategies for targeting KV channels with venom peptides, antibodies and small molecules and then highlights recent progress in the preclinical and clinical development of drugs targeting KV1.x, KV7.x (KCNQ), KV10.1 (EAG1) and KV11.1 (hERG) channels.

Introduction

After protein kinases and G-protein coupled receptors, voltage-gated-like ion channels (VGICs) constitute the third largest group of signaling molecules in the human genome1. With 78 members, potassium channels make up about half of this extended gene superfamily and can be divided into four structural types based on their mode of activation and the number of their transmembrane segments (TM): inwardly rectifying 2 TM K+ channels (Kir), two-pore 4 TM K+ channels (K2P), calcium-activated 6 or 7 TM K+ channels (KCa), and voltage-gated 6 TM K+ channels (KV). This review will focus on the largest gene family within the K+ channel group, the KV channels, which in humans are encoded by 40 genes and are divided into 12 subfamilies. Similar to the first cloned KV channel, the Drosophila Shaker channel2, all mammalian KV channels consist of four α-subunits, each containing six transmembrane α-helical segments S1–S6 and a membrane-reentering P-loop (P), which are arranged circumferentially around a central pore as homo- or heterotetramers. This ion-conduction pore is lined by four S5-P-S6 sequences while the four S1–S4 segments, each containing four positively charged arginine residues in the S4 helix, act as voltage-sensor domains and “gate” the pore by “pulling” on the S4–S5 linker3,4. For detailed discussions of the current views on electro-mechanical coupling mechanisms during the gating process interested readers are referred to several excellent reviews5,6,7.

All 40 KV channels in the human genome have been cloned and their biophysical properties characterized in minute detail, but it often remains a challenge to precisely determine what channel underlies a K+current in a native tissue. This is because within subfamilies, such as the KV1- or KV7-family, the α-subunits can heteromultimerize relatively freely resulting in a wide variety of possible channel tetramers with different biophysical and pharmacological properties8. The properties of KV channel α-subunit complexes can be further modified by association with intracellular β-subunits. For example, KV1-family channels interact through their N-terminal tetramerization (T1) domain with KVβ1–3 proteins, which form a second symmetric tetramer on the intracellular surface of the channel (Box 1 figure) and modify the gating of the α-subunits. Another class of so-called “K+ channel interacting proteins” (KChIP1–4) enhance surface expression and alter the function of Kv4 channel α-subunits8. In addition to this “mixing” and “matching” of α- and β-subunits, KV channel properties can be further modified by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, ubiquitinylation, SUMOylation and palmitoylation. In terms of drug discovery, this molecular diversity constitutes a challenge but also provides an opportunity for achieving selectivity by designing modulators that selectively target homotetramers over heteromultimers or vice versa or that bind to tissue specific β-subunits9.

Text Box 1. Venom peptides and small molecules can interact with Kv channels in multiple ways.

Structure of KV1.23 with the S5-P-S6 region colored green, the voltage-sensor domain colored light grey, the tetramerization domain colored green and the intracellular Kvβ2 subunit magenta. Only two of the four subunits are shown for clarity.

Peptide toxins (see236 for a systematic nomenclature) typically contain between 18 and 60 amino acid residues and are cross-linked by two to four disulfide bridges forming compact molecules, which are remarkably resistant to denaturation. They can affect KV channels by two different mechanisms. While toxins from scorpions, sea anemones, snakes and cone snails bind to the outer vestibule of K+ channels and in most cases insert a lysine side chain into the channel pore to occlude it like a cork a bottle237–239, spider toxins like hanatoxin, interact with the voltage sensor domain of KV channels and increase the stability of the closed state240,241. The resulting rightward shift in activation voltage and acceleration of deactivation means that the channel is more difficult to open (i.e. membrane requires more depolarization) and closes faster. These so-called “gating-modifier” toxins typically contain a cluster of hydrophobic residues on one face of the molecule and seem to partition into the membrane when they bind to the voltage sensor242,243. In contrast to peptide toxins, which affect KV channels from the extracellular side, most small molecules bind either to the inner pore, the gating-hinges or the interface between the α- and β-subunit.

Box 1. Venom peptides and small molecules can interact with Kv channels in multiple ways.

Structure of Kv1.23 with the S5-P-S6 region colored green, the voltage-sensor domain colored light grey, the tetramerization domain colored green and the intracellular Kvβ2 subunit magenta. Only two of the four subunits are shown for clarity.

Peptide toxins (see223 for a systematic nomenclature) typically contain between 18 and 60 amino acid residues and are cross-linked by two to four disulfide bridges forming compact molecules, which are remarkably resistant to denaturation. They can affect KV channels by two different mechanisms. While toxins from scorpions, sea anemones, snakes and cone snails bind to the outer vestibule of K+ channels and in most cases insert a lysine side chain into the channel pore to occlude it like a cork a bottle224–226, spider toxins like hanatoxin, interact with the voltage sensor domain of KV channels and increase the stability of the closed state227,228. The resulting rightward shift in activation voltage and acceleration of deactivation means that the channel is more difficult to open (i.e. membrane requires more depolarization) and closes faster. These so-called “gating-modifier” toxins typically contain a cluster of hydrophobic residues on one face of the molecule and seem to partition into the membrane when they bind to the voltage sensor229,230. In contrast to peptide toxins, which affect KVchannels from the extracellular side, most small molecules bind either to the inner pore, the gating-hinges or the interface between the α-and β-subunit.

Because of the concentration gradient for K+ that exists across cellular membranes, the opening of KV channels results in an efflux of positive charge, which can serve to repolarize or even hyperpolarize the membrane. In excitable cells such as neurons or cardiac myocytes, KV channels are therefore often expressed together with voltage-gated Na+ (NaV) and/or Ca2+ (CaV) channels and are responsible for the repolarization after action potential firing. Pharmacological activation of K+ channels in excitable cells consequently reduces excitability whereas channel inhibition has the opposite effect and increases excitability (Fig. 1). In both excitable and non-excitable cells KV channels further play an important role in Ca2+ signaling, volume regulation, secretion, proliferation and migration. In proliferating cells, such as lymphocytes or cancer cells, KV channels provide the counterbalancing K+ efflux for the Ca2+ influx through store-operated inward-rectifier Ca2+ channels like CRAC (calcium-release activated Ca2+ channel)10,11 or transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, which is necessary for cellular activation. In this case, KV channel blockers inhibit proliferation and suppress cellular activation10,12. In fact, it is well established that both migration and metastases require Ca2+ influx through CRAC13 or TRPV214. In this context, potassium channels have been traditionally viewed as modulators of the driving force for Ca2+ influx. However, although no KV channels have been described to possess intrinsic catalytic functions (in the sense of the protein-kinase activity of TRPM channels) they often participate in large supramolecular complexes, whose behavior can be influenced by the channel in the absence of ion flow. Therefore, non-canonical (non-conductive) properties of KV channels are increasingly found to be important15–18. KV channels can also be important in preventing depolarization following activation of electrogenic transporters such as Na+-coupled glucose and amino acid transporters in cells such as proximal tubule endothelial cells, which have to sustain large fluxes of cations or anions19. Overall, KV channels therefore constitute potential drug targets for the treatment of diverse disease processes ranging from cancer over autoimmune diseases to metabolic, neurological and cardiovascular disorders. However, KV channels, in particular Kv11.1 (hERG) with its promiscuous blocker binding pocket and its relevance for cardiac repolarization, also constitute a liability in drug discovery due to drug-induced arrhythmias. The therapeutic potential of KV channel modulation is further underscored by the phenotypes observed in transgenic mice and various human “channelopathies” which are caused by mutations in KV channel genes (see Table 1 and later sections). This article will discuss pharmacological strategies for targeting KV channels with venom peptides, antibodies and small molecules and then review recent progress in the preclinical and clinical development of drugs targeting KV1.x, KV7.x (KCNQ), KV10.1 (EAG1) and KV11.1 (hERG) channels. Channels for which there currently is no pharmacology will not be discussed in detail but are listed in Table 1 together with their potential therapeutic significance.

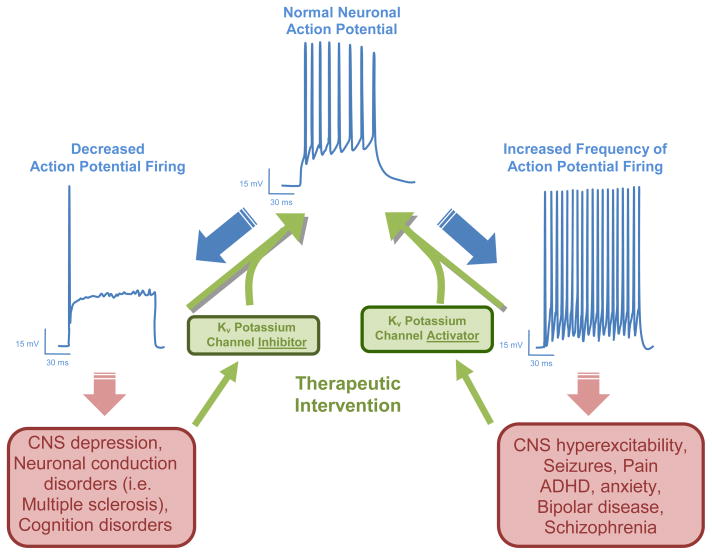

Figure 1. Theoretical effects of KV channel inhibitors and activators on pathologically altered neuronal activity.

Transmission of information within the nervous system is encoded in the frequency of electrical action potential firing in nerve fibers. Pathological changes in action potential firing frequency within the nervous system can lead to a variety of neurological and psychological disorders. Since KV channels play important roles in defining the action potential waveform, modulators of these channels are expected to have therapeutic utility in these disorders. For example, under conditions where action potential firing is decreased (i.e. depression, cognitive dysfunction) KV channel blockers should be able to restore normal firing. KV channel activators in contrast should be useful to reduce pathological hyperexcitability (i.e. epilepsy, pain) by reducing action potential firing.

Table 1.

Major expression, known channelopathies, phenotypes of transgenic mice and therapeutic significance of the 40 KV channels.

| Channel | Expression | Channelopathy | Phenotype transgenic mice | Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KV1.1 (KCNA1) | CNS (medulla, pons, cerebellum, midbrain, hippocampus, auditory nuclei), Node of Ranvier Kidney | Missense mutations cause episodic ataxia33 and primary hypomagnesemia43 | KV1.1−/−: epilepsy with spontaneous seizures31; hyperalgesia; fail to follow high-frequency amplitude-modulated sound | KV1.1 disinactivators reduce PTZ induced seizures27; suggested for epilepsy and neuropathic pain; KV1.1 blockers in clinical trials for MS40,41 and spinal cord injury38 |

| KV1.2 (KCNA2) | CNS (pons, medulla, cerebellum, hippocampus, thalamus, cerebral cortex), spinal cord | Not reported | KV1.2−/−: die on P17 from generalized seizures32; reduced NREM sleep | KV1.2 activators or disinactivators might be useful for seizure disorders |

| KV1.3 (KCNA3) | T and B cells, macrophages, microglia, osteoclasts, platelets, CNS (prominent in olfactory bulb), testis | Variant in the promoter associated with impaired glucose tolerance and lower insulin sensitivity | KV1.3−/−: increase sense of smell (“Supersmellers”)234, increased insulin sensitivity, lower bodyweight70,71 [no immune phenotype235] | KV1.3 blockers preferentially inhibit CCR7− effector memory T cells54, treat rat models of MS, RA, type-1 diabetes55, contact dermatitis68 and periodontal bone resorption |

| KV1.4 (KCNA4) | CNS (olfactory bulb, corpus striatum, hippocampus), heart, skeletal and smooth muscle, pancreatic islets | Not reported | KV1.4−/−: occasionally spontaneous seizures; no changes in cardiac Ito | Not determined |

| KV1.5 (KCNA5) | cardiac myocytes (IKur), CNS (hippocampus, cortex, pituitary), microglia, Schwann cells, macrophages vascular smooth muscle | No human mutations reported; KV1.5 expression reduced in chronic AF | KV1.5−/−: no LPS induced NO release in microglia SWAP mice (mKV1.5 replaced with rKV1.1): resistant to drug- induced prolongation of QT interval |

KV1.5 blockers in development as anti- arrhythmics for atrial fibrillation (AF)85 |

| KV1.6 (KCNA6) | Spinal cord, CNS, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, astrocytes, pulmonary artery smooth muscle | Not reported | KV1.6−/− mice commercially available; phenotype not characterized | Not determined |

| KV1.7 (KCNA7) | Heart, skeletal muscle, liver, lung, placenta, CNS | Not reported | KV1.7−/− mice commercially available; phenotype not characterized | Might be a target for atrial fibrillation similar to KV1.5 |

| KV1.8 (KCNA10) | Kidney, CNS, heart, skeletal muscle | Not reported | Not reported | Not determined |

| KV2.1 (KCNB1) | CNS (cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum), pancreatic beta cells, insulinomas, gastric cancer cell | Not reported | KV2.1−/−: reduced fasting blood glucose levels and elevated serum insulin levels106 | KV2.1 blockers suggested as hypoglycemic agents for type-2 diabetes |

| KV2.2 (KCNB2) | CNS (olfactory bulb, cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum), pancreatic delta cells | Not reported | Not reported | Not determined |

| KV3.1 (KCNC1) | CNS (cerebellum, substantia nigra, cortical and hippocampal interneurons, inferior colliculi, cochlear and vestibular nuclei), skeletal muscle, mouse CD8+ T cells | Not reported | KV3.1−/−: reduced body weight, impaired motor skills, sleep loss [KV3.1/KV3.3 double knockout: severe myoclonus and hypersensitivity to ethanol] |

Not determined |

| KV3.2 (KCNC2) | CNS (fast spiking GABAergic interneurons), pancreatic islets, Renshaw cells (spinal interneurons), pancreatic beta cells | Not reported | KV3.2−/−: Alterations in cortical electroencephagraphic patterns and increased seizure susceptibility | Not determined |

| KV3.3 (KCNC3) | CNS (brainstem, cerebellum, forebrain, Purkinje cells, motorneurons, auditory brainstem) | Missense mutations cause SCA13 (spinocerebellar ataxia 13) |

KV3.1/KV3.3 double knockout: severe myoclonus and hypersensitivity to ethanol (KV3.3−/−: no overt phenotype) | Not determined |

| KV3.4 (KCNC4) | CNS (brainstem, hippocampal granule cells), skeletal muscle | Missense mutation in the beta-subunit KCNE3 (MiRP2) causes periodic paralysis111 | Not reported | KV3.4 blockers suggested for Alzheimer’s disease112,113 |

| KV4.1 (KCND1) | CNS, heart, liver, kidney, thyroid gland, pancreas | Not reported | Not reported | Not determined |

| KV4.2 (KCND2) | CNS (cerebellum, hippocampus, thalamus, forebrain, dorsal horn neurons), heart [rodents] | Truncation mutations cause temporal lobe epilepsy | KV4.2−/−: Enhanced sensitivity to tactile and thermal stimuli; Ito,f eliminated [in mice Ito,f is a heteromultimer of KV4.2 and KV4.3] | KV4.2 activators might be useful for inflammatory pain119 |

| KV4.3 (KCND3) | Heart, CNS (cortex, cerebellum), atrial and ventricular myocytes (Ito) smooth muscle | Not reported | Not reported | KV4.3 blockers might be useful as antiarrhythmics [in humans Ito,f is a KV4.3 homotetramer117] |

|

KV5.1 (KCNF1) |

KV5 and KV6 channels are not functional alone. They coassemble with KV2 subunits and act as modifiers or silencers. | |||

| KV6.1 (KCNG1) | ||||

| KV6.2 (KCNG2) | ||||

| KV6.3 (KCNG3) | ||||

| KV6.4 (KCNG4) | ||||

| KV7.1 (KCNQ1) | Heart, ear, skeletal muscle, liver, epithelia in kidney, lung, gastrointestinal tract | Loss-of-function mutations lead to Type 1 Long QT Syndrome123 or Jervell and Lange- Nielsen Syndrome124; Gain-of-function mutations lead to Familial Atrial Fibrillation126, short QT Syndrome125 or type-2 diabetes mellitus146 | KV7.1−/− mice are deaf and have abnormal cardiac ECG T- and P- wave morphologies and prolongation of QT interval | KV7.1 inhibitors in development for treating atrial arrhythmias134 KV7.1 openers suggested for treatment of Long QT syndrome |

| KV7.2 (KCNQ2) | CNS (hippocampus, cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, brain stem, nodes of Ranvier); sympathetic and dorsal root ganglia | Loss of function mutations lead to benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC)149 | Homozygous (KV7.2−/−) die within a few hours after birth; heterozygous KV7.2+/− mice show hypersensitivity to pentylenetetrazole induced seizures | KV7.2/7.3 inhibitors historically developed for treatment of learning and memory disorders154, 155 |

| KV7.3 (KCNQ3) | CNS (hippocampus, cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, brain stem), nodes of Ranvier; sympathetic and dorsal root ganglia | Loss of function mutations lead to benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC) | Mouse models of human KV7.3 (and KV7.2) mutations for BFNC exhibit seizures | KV7.2/7.3 activators in development for the treatment of epilepsy160,162,166 and pain168. Suggested for treatment of migraine, ADHD, bipolar disease, schizophrenia182 and bladder contractility disorders |

| KV7.4 (KCNQ4) | Outer hair cells and neurons of auditory system, vascular smooth muscle | Loss of function mutations leading to deafness autosomal dominant 2a (DFNA2A)152, 153 | KV7.4−/− mice have a degenerative loss of outer hair cells and accompanying loss of hearing | KV7.4 activators may have therapeutic utility in the treatment of hearing disorders |

| KV7.5 (KCNQ5) | CNS (hippocampus, cortex, thalamus), skeletal muscle, vascular smooth muscle | Not reported | Phenotype not reported | Not determined |

| KV8.1 (KCNV1) | KV8 and KV9 channels are not functional alone. They coassemble with KV2 subunits and modify their function. | |||

|

KV8.2 (KCNV2) | ||||

| KV9.1 (KCNS1) | ||||

| KV9.2 (KCNS2) | ||||

| KV9.3 (KCNS3) | ||||

| KV10.1 (KCNH1, eag-1) | CNS | Aberrantly expressed in cancer12,188 | Slight tendency to seizures | KV10.1 inhibitors for cancer204 |

| KV10.2 (KCNH5, eag-2) | CNS, muscle, heart, placenta, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas | Not reported | Not reported | Not determined |

| KV11.1 (KCNH2, erg-1, HERG) | Heart, CNS, endocrine cells, lymphocytes | KV11.1 mutations cause Type 2 LQT24,206 | Paroxistic bradychardia (HERGB); N629D lethal due to cardiac malformation | KV11.1 blockers suggested for arrhythmia (liability for drug-induced LQT) and cancer treatment |

| KV11.2 (KCNH6, erg-2) | CNS, endocrine cells | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| KV11.3 (KCNH7, erg-3) | CNS | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| KV12.1 (KCNH8, elk-1) | CNS | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| KV12.2 (KCNH3, elk-2) | CNS | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| KV12.3 (KCNH4, elk-3) | CNS | Not reported | Not reported | None reported |

For a complete reference list containing gene and protein accession numbers, chromosomal location, splice variants, expression, physiological role, mutations and pharmacology please see the IUPHAR database of voltage-gated potassium channels at http://www.iuphar-db.org/PRODIC/FamilyMenuForward?familyId=16

Pharmacological strategies for modulation of KVchannel function

Agents that modulate KV channels broadly fall into three chemical categories: metal ions, organic small molecules (MW 200–500 Da) and venom-derived peptides (MW 3 to 6 kDa)9. These substances affect KV channel function by blocking the ion-conducting pore from the external or internal side or modifying channel gating through binding to the voltage-sensor domain or auxiliary subunits (Box 1). Similar to other proteins expressed on the cell surface, KV channels can also be targeted with antibodies (MW 150 kDa), which can either “simply” inhibit channel function, lead to channel internalization or deplete channel-expressing cells by complement or cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Antibodies and toxins can also be engineered to serve as carriers for delivery of active compounds to channel-expressing cells, or can be conjugated to cytotoxic drugs, isotopes or other molecules. In terms of channel inhibition, monoclonal antibodies have been reported in just one case (Kv10.1), although polyclonal antibodies have been obtained in several cases using extracellular parts of the pore loop as antigen20.

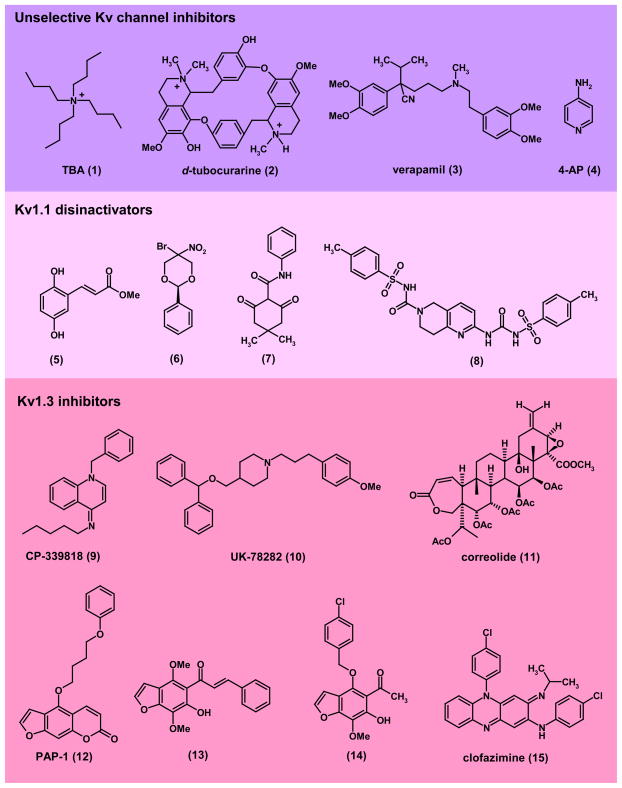

While peptide toxins typically bind either to the outer vestibule or the voltage-sensor of KV channels, small molecules, as exemplified by the hydrophobic cations tetrabutylammonium (1, Fig. 2), d-tubocurarine (2), and verapamil (3), block KV channels by physically occluding the inner pore and inserting their ammonium group into the ion permeation pathway (Box 1). The inner pore of KV channels can also be targeted by nucleophilic molecules like the KV1 channel blocker correolide (11), which “snuggles” into the hydrophobic surface of the S6 helix with its lipophilic part and chelates a permeating potassium ion with its polar acetyl groups21. Typical blockers of KV11.1 enter the channel from the intracellular side and appear to reside in a pocket in the inner mouth, where they interact mostly with two aromatic residues22. The large variety of drugs that this pocket can accommodate might be attributable to the lack of a cluster of prolines that induces a kink in the inner mouth of KV channels, in contrast to other families23. This leaves a broader opening in KV11.1 that allows entry of a wide range of molecules of varying sizes and shapes24. In addition to the inner pore, small molecules can further bind to the “gating-hinges” as in the case of the KV7 channel activator retigabine, which has been found by mutagenesis to bind to a putative hydrophobic pocket formed upon channel opening between the cytoplasmic parts of S5 and S625. Another interesting mechanism of action for channels with β-subunits are the so-called disinactivators that disrupt the interaction between α- and β-subunits and modify channel behavior in this way26,27. However, rational design of KV channel modulators is extremely difficult because there are currently no crystal structures for medically important KV channels like KV1.5, KV7.2 or KV11.1. Overall, the KV channel field only has two structures, the bacterial KvAP and the mammalian KV1.2 channels (both in the open state) and no structure of a channel with a drug molecule bound. KV channel modulators are therefore typically identified through high-throughput-screening (See Box 2) or serendipity and then optimized through classical medicinal chemistry. Lead identification is usually performed by ion flux assays (mostly using isotopes and/or atomic absorption spectroscopy) or fluorescent dye assays28, and more recently through automated electrophysiology, which can offer quality levels comparable to manual patch-clamp with a reasonable throughput. Detailed studies on functional drug-target interactions can be achieved through patch-clamping, which allows the behavior of a single ion channel to be studied on the microsecond time scale.

Figure 2. Structures of unselective Kv channel blockers and Kv1-family channel modulators. Unselective KV channel inhibitors:

(1), TBA (tetrabutyl ammonium); (2), d-tubocurarine; (3), verapamil; (4), 4-AP (4-aminopyridine). 4-AP recently completed Phase-3 clinical trials for multiple sclerosis40,41. Kv1.1 disinactivators: (5), methyl 2,5-dihydroxycinnamate26; (6), cylohexadione compound-5 (Wyeth)27; (7) 1,3-dione-2-carboxamide compound-2 (Wyeth)27, (8) N-tosyl-2-(3-tosylureido)-7,8-dihydro-1,6-naphthyridine-6(5H)-carboxamide compound-6 (Lectus Therapeutics)36. Kv1.1 disinactivators prevent seizures in miceand have been suggested for the treatment of epilepsy and pain KV1.3 inhibitors: (9), CP-339818 (Pfizer); (10), UK-78282 (Pfizer); (11), correolide (Merck); (12), PAP-1 (UC Davis)65; (13), khellinone chalcone (University of Melbourne)66; (14), 4-substituted khellinone (University of Melbourne)67; (15), clofazimine69. Kv1.3 blockers effectively treat autoimmune disease models in rats and pigs and are therefore regarded as promising new immunosuppressants.

Text Box 2. Ion channel screening technologies.

Implementing successful drug discovery campaigns against KV channels has been, and continues to be challenging. One of the reasons for this is that the traditional technologies used to measure ion channel function have not always been translatable to the high throughput world of drug discovery. Electrophysiology such as cellular voltage-clamp, and in particular the patch-clamp variant of this technique, has been the “gold standard“ for measuring ion channel function for nearly three decades244. It is a high fidelity, but low throughout platform that requires skilled operators. While this technology can teach much about the biophysical properties and modulation of ion channels in general and KV channels in particular, it can only be used to examine a few compounds per day and is impractical in modern drug discovery, where hundreds of thousands, and sometime times millions of compounds need to be tested for activity. In order to enable drug discovery against ion channels, a number of technologies have been developed. As with many drug target classes, radioligand binding studies have been employed with some success to identify modulators of KV channels. Radioiodinated venom toxins like margatoxin245 or tritiated natural products like correolide246 have been used to look for modulators of KV1.3 channels; radiolabeled dofetilide is used regularly in assays to look for potential modulators of KV11.1 (hERG)247. While radioligand binding assays can be very high throughput, ligands identified by this technique do not always have functional activity. Examining KV channel function more directly in flux assays can get around this issue. Historically, radiolabelled86 rubidium ions have been used as a surrogate for potassium in high throughput flux assays for a variety of potassium channel targets248. Radioactive rubidium can also be replaced by unlabelled rubidium and then be detected by atomic absorption spectroscopy249. More recently, thallium, which is also permeant through potassium channels, has been used successfully in high throughput screening assays, where upon fluxing through open channels it interacts with a preloaded intracellular fluorescent dye250. Membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dyes have also been used successfully to examine compound interactions with KV channels251. However, perhaps the biggest impact on ion channel drug discovery in recent years has been the development of higher throughput electrophysiological platforms. These range from the medium throughput systems like the high fidelity PatchXpress (Molecular Devices)252, Qpatch (Sophion)253,254 or PatchLiner (Nanion)255, which can test up to a 100 compounds per day to higher throughput platforms like IonWorks HT and Quattro (Molecular Devices)256,257 and more recently Qpatch HTX (press release from Sophion) that can test thousands of compounds per day. While not truly high throughput, when used in conjunction with other screening technologies, these new electrophysiology platforms have allowed for a higher fidelity and a more direct approach to KV channel drug discovery. More detailed discussions of screening for ion channel modulators can be found in the following recent reviews28,258,259.

KV1-Family Channels

Channels belonging to the KV1.x or mammalian Shaker-family are widely expressed throughout the nervous system. Of the eight known pore forming subunits of this family (KV1.1- KV1.8), most have been shown to form heteromultimers in the CNS. Therefore, the exact composition of neuronal KV1.x channels remains to be fully elucidated. However, in general, most forms of neuronal KV1.x channels are believed to contain at least one KV1.1 and/or KV1.2 subunit29 and these two channels are therefore regarded as targets for various CNS disorders. KV1.x family channels are further found in peripheral tissues such as the heart, the vasculature and the immune system, where KV1.5 and KV1.3 are pursued respectively as targets for atrial fibrillation and immunosuppression. The therapeutic relevance of KV1.4, KV1.6, KV1.7 and KV1.8 is currently not clear.

KV1.1 and KV1.2

The importance of KV1.1 and KV1.2 in controlling neuronal excitability has been demonstrated by the observation that KV1.x channel inhibiting venom toxins like dendrotoxin produce seizures in rodents30. Furthermore, KV1.1−/− transgenic knockout mice exhibit spontaneous seizures and CNS structural changes31. Similarly, knockout of KV1.2 in mice is also associated with increased susceptibility to seizures32. In humans, several loss-of-function mutations in KV1.1 have been linked to partial seizures, episodic ataxia and myokymia disorders33. Moreover, loss-of-function mutations in a protein called LGI1, which is co-expressed with KV1.1, have been associated with temporal lobe epilepsy34. While normal LGI1 protein functions to inhibit KVbeta (KVβ1) subunit mediated inactivation of KV1.1/KV1.4 heteromultimeric channels, increasing potassium current and lessening neuronal excitability, mutated LGI1 lacks the ability to abrogate β-subunit mediated inactivation34.

Researchers at Wyeth have identified several small molecule agents that functionally behave like LGI1 and reverse or prevent KVβ1 mediated inactivation of KV1.1. Using a variety of techniques including a yeast two hybrid based screen they identified inhibitors (termed “disinactivators”) of protein/protein interactions between β- and pore forming α-subunits26,27. Several structural classes of compounds (see Fig. 2 for examples) have been reported to interact directly with the KVβ1 N-terminus or its receptor site on KV1.1, preventing inactivation of the channel. In addition to increasing current flow, these KV1.1 disinactivators effectively reduce pentylentetrazole and maximal electric shock induced seizures in mice27. Accordingly, compounds acting by this mechanism have the potential to reduce neuronal hyperexcitability in epilepsy and pain disorders. However, the current development status of this therapeutic strategy is unknown. Utilizing a different screening strategy termed Leptics™ technology35, investigators at Lectus Therapeutics have recently identified both activators and inhibitors of Kv1.1 function that modulate β-subunit protein-protein interactions with KV1.x pore forming α-subunits36.

While activation of KV1.1/1.2 channels is expected to reduce neuroexcitability (Fig. 2), there are physiological and pathophysiological situations where electrical signaling in the nervous system is reduced and needs to be amplified. Damage to nerves caused by trauma (i.e. spinal cord injury) or disease (i.e. multiple sclerosis) is often associated with a decreased ability to generate and propagate action potentials37,38. Neuronal damage is typically manifested as a loss of myelin, resulting in the exposure of juxtaparanodal KV1.1 and KV1.2 channels and their redistribution along damaged axons37,39. The presence of newly exposed KV channels slows and sometimes prevents conduction of electrical signals along the axon. Studies have shown that inhibition of these axonal KV1.1 and KV1.2 channels by the non-selective potassium channel inhibitor 4-AP (4-aminopyridine, 4) improves impulse conduction in damaged nerve fibers. This resulted in speculation that 4-AP might provide a treatment opportunity for spinal cord injury37, a hypothesis tested by Acorda Therapeutics. However, despite encouraging phase-II clinical data with a slow release formulation of 4-AP, Fampridine-SR, two subsequent larger Phase-3 clinical studies in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI), failed to produce any statistically significant reduction in spasticity38. However, Acorda Therapeutics has continued to evaluate 4-AP, and recently reported on phase-III clinical studies where Fampridine-SR was found to improve walking ability in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)40,41. While these results represent significant progress in treating the symptoms of MS, the impact of Fampridine-SR on actual disease progression remains to be determined.

Although typically considered a neuronal channel, KV1.1 has recently been linked to human autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia42. A loss-of-function mutation in KV1.1 reduces TRPM-6 mediated magnesium reabsorption in the kidney, which depends on KV1.1 setting a negative membrane potential43. Because of its fundamental role in many cellular functions, abnormalities in magnesium levels can result in widespread organ dysfunction, which can precipitate potentially fatal complications (e.g. ventricular arrhythmia, coronary artery vasospasm, seizures). Pharmacological enhancement of available Kv1.1 channel activity might provide a therapeutic opportunity for treating hypomagnesemia.

KV1.3

KV1.3 was discovered in human T cells in 198410,44,45 and proposed as a target for immunosuppression based on the fact that non-selective K+ channel blockers like 4-AP (4) inhibit T cell proliferation and IL-2 secretion44. Investigators at Merck later confirmed these findings with the more KV1.3-selective scorpion toxin margatoxin46 and also provided the first evidence that KV1.3 blockade can inhibit immune responses in vivo by demonstrating that continuous infusion of margatoxin suppressed delayed type hypersensitivity in mini-pigs47. KV1.3 blockers exert their immunosuppressive effect by depolarizing the T cell membrane46 and thus reducing the driving force for Ca2+ entry through the calcium-release activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel10, which consists of the ER Ca2+-sensor STIM1 and the pore forming protein Orai111,48–50. Since T cells are small and have no significant intracellular calcium stores, this Ca2+ influx through the inward-rectifier CRAC is absolutely necessary for the translocation of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) to the nucleus and the ultimately resulting cytokine secretion and T cell proliferation. The T cell must therefore retain a negative membrane potential through a counterbalancing K+ efflux through KV1.3 and/or the other T cell K+ channel, the Ca2+-activated channel KCa3.1, in order to be fully activated.

In the mid-1990s, Merck and Pfizer initiated small molecule KV1.3 discovery programs but failed to identify compounds that were selective enough for in vivo use51. The Pfizer compounds CP-339818 (9, Fig. 2) and UK-78282 (10) lacked selectivity over Na+ channels or KV1.4, while the molecular complexity of Merck’s nor-triterpene correolide (11) was too great for successful analogue development. Interest in KV1.3 as a target for immunosuppression subsequently waned, partially because species differences in T cell K+ channel expression between mice and humans made it impossible to use the well-established mouse models of autoimmune diseases to evaluate KV1.3 blockers. Interestingly, mice express additional KV channels like KV1.1, KV1.6 and KV3.1 in their T cells47,52,53 and do not rely on KV1.3 to set their resting membrane potential. However, interest in Kv1.3 as a drug target recently revived considerably with the discovery that Kv1.3 blockers selectively inhibit the Ca2+-signaling, proliferation and in vivo migration of CCR7− effector memory T cells54–56 and therefore rather constitute immunomodulators instead of general immunosuppressants57. So-called effector memory T cells (TEM) are a memory T cell subset that is negative for the chemokine receptor CCR7 and which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases such as MS, type-1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriasis55,58–61. In keeping with this observation, myelin antigen reactive T cells in the blood from MS patients, islet antigen reactive T cells from new onset type-1 diabetic children as well as synovial fluid T cells from patients with RA and brain infiltrating T cells in postmortem brain sections from MS patients have all been demonstrated to be KV1.3high CCR7− TEM cells54,55,61. [Similar to humans, rats, pigs, and primates up-regulate KV1.3 in their effector memory T cells making it possible to evaluate the immunosuppressive effects of KV1.3 blockers in these species.]

The possibility that KV1.3 could serve as a target for TEM specific immunosuppression has led to the recent development of both peptidic and small molecule KV1.3 blockers. After demonstrating that the sea anemone peptide ShK effectively treats adoptive-transfer experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in rats62, George Chandy’s group more recently described ShK-L563, a ShK derivative with improved selectivity over KV1.1, and showed that it treats pristane-induced arthritis and chronic-relapsing EAE in rats55,56. A close-structural analog of ShK-L5 is currently in preclinical development for MS by Airmid and Kineta Inc., while Amgen Inc. is making efforts to prolong the short half-life of venom peptides like ShK or the scorpion peptide OSK1 by conjugating them to Fc antibody fragmentsor polyethylenglycol (PEG) 64.

Starting from two natural products, the psoralen 5-methoxypsoralen from the rue plant and the benzofuran khellinone from the toothpickweed, academic laboratories at the Universities of California, Davis and Melbourne have developed several classes of nanomolar to low micromolar KV1.3 inhibitors65–67. The most potent of these compounds, the psoralen PAP-1 (12), inhibits KV1.3 with an IC50 of 2 nM and has been shown to effectively treat rat allergic contact dermatitis68, a simple animal model for psoriasis, and to prevent spontaneous autoimmune diabetes in diabetes-prone Biobreeding Worchester rats55. The khellinone-type KV1.3 blockers (as exemplified by the chalcone (13) and the 4-substituted khellinone (14)) are currently being further optimized by the Australian Biotech company Bionomics, which has entered into an agreement with Merck-Serono to develop this class of compounds for MS. KV1.3 was recently further corroborated as a target for immunosuppression in humans by the finding that clofazimine (15), a drug that is marketed as Lamprene® by Novartis and which has been clinically used since the 1960s for leprosy, pustular psoriasis, skin graft-versus-host-disease and discoid lupus erythematosis, inhibits KV1.3 with an IC50 of 400 nM and prevents the rejection of transplanted human foreskin in immunodeficient mice reconstituted with human T cells69. Clofazimine could therefore either be used as a template for the design of KV1.3 blockers of a different chemotype or could directly enter clinical trials after careful consideration of its benefit versus its known risks such as gastrointestial intolerance and skin discolorations. Results obtained with clofazimine should of course be interpreted with caution since the compound has multiple activities on other targets and pathways such as stimulation of phospholipases, increasing phagocytosis by macrophages or interactions with DNA.

Based on experiments with KV1.3−/− mice, these channels have also been suggested as a target for the treatment of type-2 diabetes and obesity70. KV1.3−/− mice were reported to gain less weight on a high-fat diet than KV1.3+/+ littermates and to exhibit increased insulin sensitivity due to increased glucose uptake into adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. In these tissues in normal mice, blockade of KV1.3 with margatoxin facilitates the translocation of the glucose transporter, GLUT4, to the plasma membrane and thus improves insulin sensitivity71. Intriguingly, deletion of KV1.3 can also reduce adiposity and increase lifespan in a genetic model of obesity. Double KV1.3 and melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) knockout mice exhibited a lower bodyweight, an increased lifespan and reproductive success compared to MC4R−/− mice72. However, while it is certain that mouse adipocytes express KV1.3 protein, electrophysiological studies performed with neonatal brown fat cells73,74 and white adipocytes from rats and adult humans75,76 show KV currents with properties that do not fit the pharmacological and biophysical characteristics of a current that is carried by KV1.3 channel homotetramers. It therefore remains to be seen whether or not KV1.3 constitutes a target for the improvement of insulin sensitivity and weight reduction in type-2 diabetes in humans.

KV1.5

Although KV1.5 is expressed in a variety of tissues in humans77–79, its functional expression in atrial but not ventricular muscle in heart77 has made this channel the focus of great interest within the pharmaceutical industry. Studies by Nattel and colleagues in the early 1990s demonstrated that KV1.5 was the primary molecular component of the ultra rapid delayed rectifier (IKur)80,81, a human atrial specific potassium conductance that plays an important role in the early phases of atrial action potential repolarization82 (Fig. 3a). This mechanism, and its regiospecific localization, suggested KV1.5 as an attractive target for the development of safer pharmacological interventions for atrial arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation (AF). The absence of functional KV1.5 expression in human ventricle reduces the potential risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias that can occur with treatments targeting channels with broader expression within the heart83,84. Given the ubiquitous expression of other KV1.x channels, there has been a desire to identify and develop KV1.5 selective agents. Development has been complicated by the fact that the importance of IKur, or the contribution of KV1.5 to IKur-like currents to atrial action potential repolarization in the hearts of mice, rats, rabbits and dogs may differ from humans, making it difficult to evaluate anti-arrhythmic efficacy in these species84,85.

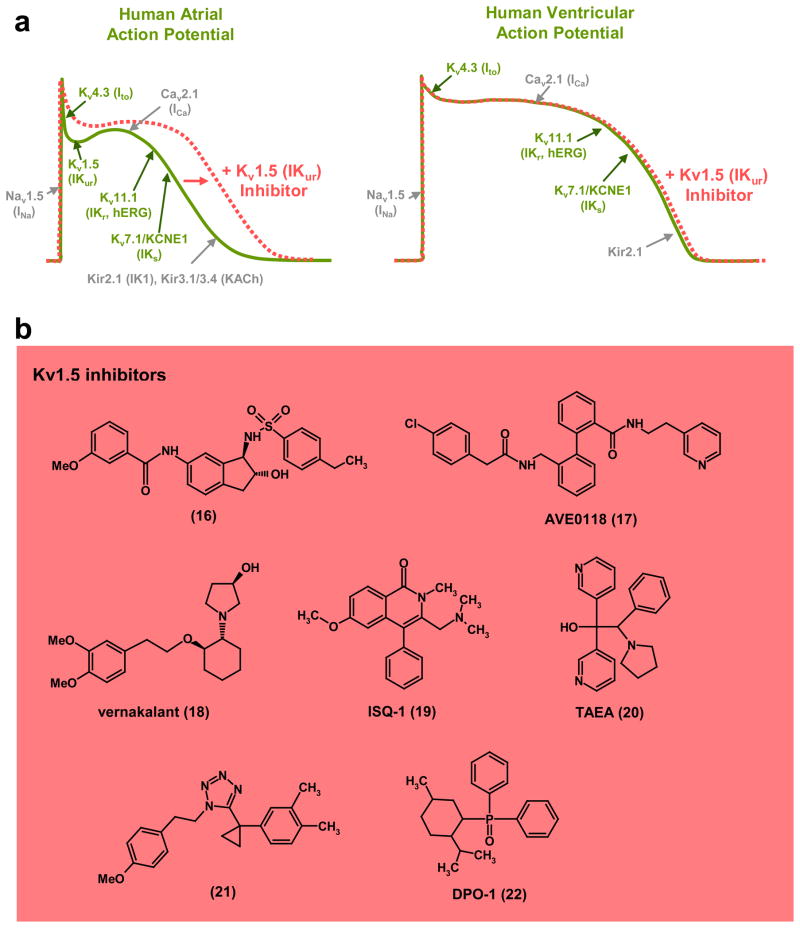

Figure 3. KV1.5 inhibitors as atrial selective antiarrhythmic agents.

a, Schematic of a human atrial and ventricular action potential and the underlying ionic conductances (voltage-gated potassium (KV) channels shown in green; other classes of ion channel shown in grey) that define the waveform. Kv1.5 (IKur) is only expressed in atrial myocytes and KV1.5 blockers therefore selectively prolong the action potential duration in the atrium. b, Structures of KV1.5 inhibitors: (16), arylsulphonamidoindane (Icagen/Lilly)86; (17), AVE0118 (Sanofi-Aventis)89,90; (18), vernakalant (Cardiome)96,97; (19), ISQ-1 (Merck)93; (20), TAEA (Merck)93; (21), tetrazole derivative (Procter & Gamble)95; (22), DPO-1 (Merck)92. Several Kv1.5 blockers have been or are in clinical trials for the treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Despite these challenges, a number of pharmaceutical companies have attempted to develop KV1.5 inhibitors for AF (Fig. 3b). Over 50 patent applications for KV1.5 inhibitors have been submitted (see85 for a comprehensive review). One of the earliest attempts was by Icagen Inc., who in collaboration with Eli Lilly and then with Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), identified a number of potent KV1.5 inhibitors from multiple chemotypes including arylsulphonamidoindanes86 (16) and later tetrahydronapthalenes, but ultimately abandoned them because of poor pharmacokinetic profiles. Other compounds from the Icagen/BMS collaboration entered human clinical trials although they were not progressed beyond phase-I. Bristol Myers Squibb87, Sanofi-Aventis83,88–90, Merck91–93, Procter and Gamble94,95, Cardiome/Astellas96–98, and Wyeth99 have also developed KV1.5 inhibitors (17–22), demonstrating varying degrees of validation with regard to atrial-specific modulation of action potential repolarization, but the majority of these compounds have not progressed beyond animal efficacy testing due to pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic issues. However, the bisaryls AVE0118 (17) and AVE1231 from Sanofi-Aventis89,90,100,101, although at best weakly selective for KV1.5, have progressed into human testing, with AVE0188 reaching phase-IIa trials before development ceased. Canadian based Cardiome, in collaboration with Merck, is currently in the final development stages of vernakalant (18) after a completed Phase-III study gained conditional FDA approval for intravenous conversion of AF. This compound has previously been shown to reduce AF in a variety of animal models97,98. Although KV1.5 has been argued to be the primary target of vernakalant, its mechanism of action probably involves blockade of several ion channels including Ito, and INa97 (see Fig. 3a). Xention has recently reported the development of a selective KV1.5 inhibitor, XEN-D010185, which was effective in two preclinical canine models of AF102,103 and is currently undergoing Phase-I evaluation as an intravenous treatment to terminate AF.

KV2.1

KV2.1 encodes a classical delayed rectifier current involved in neuronal repolarization and its function can be diversified through heteromultimerizaton with the so-called “silent” KV5, KV6, KV8 and KV9 subunits (Table 1), which modify inactivation, trafficking, drug sensitivity and expression104,105. KV2.1 has been recently implicated in exocytic processes both in neurons and in pancreatic β–cells. In β–cells, inhibition of KV2.1 enhances insulin secretion, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy for type-2 diabetes mellitus106,107. This effect apparently occurs (at least in part) through non-conducting functions, namely a physical interaction with syntaxin (a component of the SNARE complex) that facilitates vesicle fusion108,109.

KV3.4

Of the Shaw-related family of mammalian KV channels, so far only KV3.4 has been proposed as a drug target. KV3.4 co-assembles with KCNE3 (MIRP2) to give rise to a fast inactivating (Atype) KV current in skeletal muscle and neurons110. In muscle, alterations in the function of the complex, through mutations in the accessory subunit KCNE3, are associated with periodic paralysis111. Additionally, in nervous tissue, KV3.4 has been related to neuronal death induced by β-amyloid peptides in Alzheimer’s disease112,113. Potassium depletion through hyperactivity of KV channels contributes to apoptotic neuronal death114, while blockade of K+ channels has neuroprotective effects115. The expression of KV3.4 is increased in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and increases further as the disease advances112. Together with higher expression levels, the current carried by KV3.4 is enhanced by β-amyloid peptide, while the KV3.4-blocking anemone toxin BDS simultaneously abolishes current increase and neuronal death113. Hence, blockade of KV3.4 in the context of Alzheimer’s disease could reduce neuronal loss and thereby cognitive impairment.

KV4.2/KV4.3

The Shal-type KV4.2 and KV4.3 channels are expressed at relatively high levels in the brain and the heart, where they contribute to the transient A-type or Ito current (Fig. 3a). One remarkable feature of KV4 channels is the complexity of their association with various ancillary subunits or scaffolding proteins and their extensive posttranslational modification116. In terms of drug discovery, atrial and ventricular KV4.3 channels could potentially constitute targets for antiarrhythmic therapy and inhibition of Ito, which in humans consists of a KV4.3 homotetramer117, seems to be one of the mechanisms of action of the class III antiarrhythmic tedisamil. However, in addition to Ito tedisamil, which is being developed by Solvay also inhibits IKr, IKs, IKur and IK-ATP118. The FDA recently rejected an application for the use of tedisamil for the treatment of atrial arrhthymias. Future development of this compound remains unclear. Based on the important role of KV4.2 in pain plasticity in dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord119 KV4.2 activators might be useful for the treatment of inflammatory pain.

KV7-Family Channels

The KV7.x or KCNQ family comprises five members: KV7.1 to KV7.5. While KV7.1 (KCNQ1) is predominantly found in peripheral tissues, KV7.2 –7.5 (KCNQ2–5) appear to be most widely expressed in the nervous system120,121.

KV7.1

KV7.1 is present in cardiac muscle where it is coexpressed with the auxiliary subunits KCNE1, KCNE2 and KCNE3 to form the functional channel responsible for the slow delayed rectifier current IKs120,122. This current plays an important role in controlling repolarization, and thus duration, of the cardiac action potential (Fig. 4a). In humans, numerous loss-of-function mutations of KV7.1 or KCNE (resulting in reduced current flow and prolongation of cardiac action potentials) have been identified in potentially life threatening cardiac abnormalities such as Long QT syndrome120,123. Several of these loss-of-function mutations in KV7.1 are also associated with Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome124, a condition with auditory abnormalities in addition to cardiac rhythm defects. Gain-of-function mutations in KV7.1 increase current flow and lead to shortening of the cardiac action potential and are associated with cardiac rhythm disorders such as Short QT syndrome125 and atrial fibrillation 126.

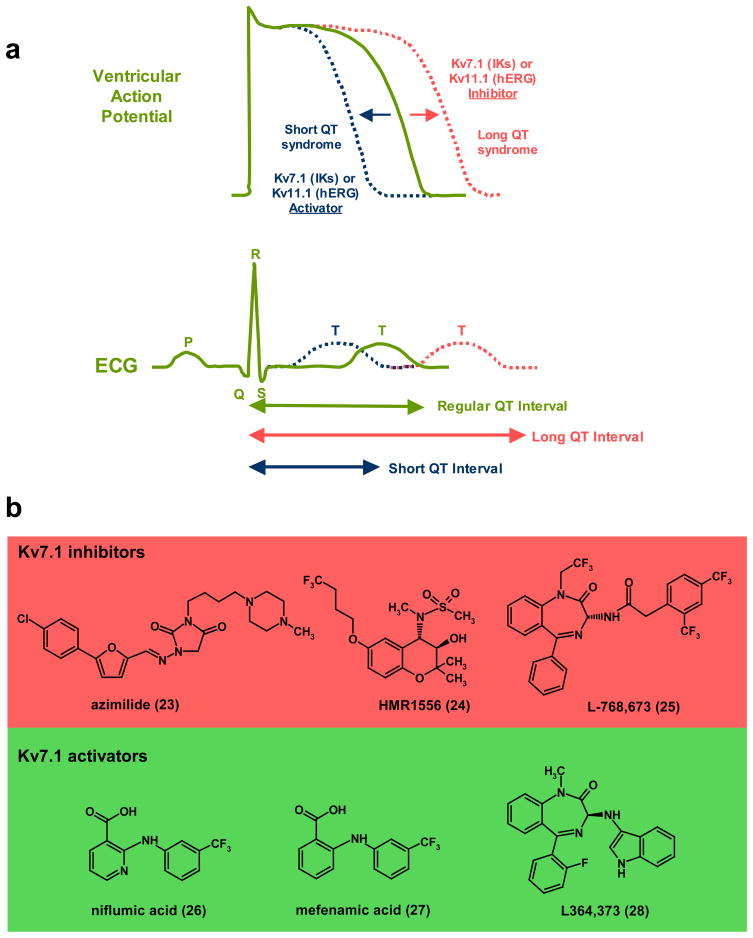

Figure 4. KV7.1 and KV11.1 are crucial for determining the length of the cardiac action potential.

a, Illustration of ventricular action potential (AP) and electrocardiogram (ECG) showing effects of Long- and Short-QT syndrome as well as pharmacological modulators of KV7.1 (IKs) or KV11.1 (hERG) on AP duration and length of QT interval. Inhibition of KV7.1 and KV11.1 produces prolongation of ventricular AP duration which is similar to what occurs in acquired or hereditary Long QT syndrome. Activators of KV7.1 or KV11.1 reduce the duration of cardiac action potential which is manifested as a shorter QT interval b, KV7.1 inhibitors: (23), azimilide (Procter & Gamble)128,129; (24), HMR1556 (Sanofi-Aventis)134; (25), L768,673 (Merck)138. Azimilide has been shown to reduce atrial fibrillation (AF) in clinical trials128,129, while HMR1556 and L768,673 are effective in dog models of AF. KV7.1 activators: (26), niflumic acid139; (27), mefenamic acid139; (28), L384,373 (Merck)141.

For more than a decade, IKs has remained a target of interest for the development of anti-arrhythmic drugs. Some marketed anti-arrhythmic agents (i.e. amiodarone) may produce their clinical effects in part through modulation of KV7.1/KCNE activity127. Azimilide (23, Fig. 4b), a mixed inhibitor of KV7.1 (IKs) and KV11.1 (IKr) developed by Procter & Gamble has exhibited efficacy in a variety of animal arrhythmia models128,129. However, when assessed in human clinical trials, only limited efficacy in the conversion of atrial fibrillation has been observed130–132. The current development status of azimilide is unknown. Selective inhibitors of KV7.1 like the chromanol HMR1556 (24) from Sanofi-Aventis133,134 and L-768,673 (25) from Merck have also been reported to prolong cardiac action potentials and reduce the incidence of arrhythmias in animal models. HMR1556 - which has greater than 1000-fold selectivity for IKs over IKr, restores sinus rhythm and prevents heart failure in pigs with persistent atrial fibrillation135,136. However, in a canine model of vagal AF, HMR1556 prolonged the atrial effective refractory period, but exerted only a modest effect on the duration of induced AF137. The acyl benzodiazepine, L-768,673 developed by Merck has been reported to increase ventricular refractoriness in conscious dogs138. Despite their activities in animal models, neither of these selective KV7.1 inhibitors appears to have been assessed for clinical efficacy in humans.

In addition to inhibitors, several pharmacological activators of KV7.1 (± KCNE1) channels have been reported. Niflumic acid (26) and structurally related mefenamic acid (27) increase current flow through KV7.1/KCNE1 by inducing hyperpolarizing shifts in the voltage-dependence of activation139. Investigators at Merck have demonstrated that the benzodiazepine L-364,373 (28) potently activates homomeric KV7.1 channels but is considerably weaker when KV7.1 coexpresses with the auxiliary subunit KCNE1 (as occurs in the heart)140,141. The utility of KV7.1 activators in a therapeutic setting remains to be evaluated.

Although most well characterized in the heart, KV7.1 is found in the inner ear and epithelial tissues of the kidney, lung and gastrointestinal tract120. In contrast to the heart, KV7.1 channels in epithelial cells appear to primarily coexpress with KCNE3 to form a conductance that exhibits little time dependence with regard to activation and only weak sensitivity to membrane potential142. Gating of the channel is modulated via a variety of second messenger pathways including cyclic AMP143,144. Epithelial KV7.1 channels play an important role in maintaining the driving force for proximal tubular and intestinal Na+ absorption, gastric acid secretion, and cAMP-induced jejunal Cl− secretion120,145. Recent studies have also revealed an association of KV7.1 with the susceptibility to type-2 diabetes mellitus146. KV7.1 activity seems to neutralize the stimulation of cellular K+ uptake into liver by insulin and thereby influences K+-dependent insulin signaling147. The therapeutic utility of targeting KV7.1 for diabetes or epithelia fluid transport disorders is an area that remains to be explored.

KV7.2–KV7.5

Over the past decade there has been considerable interest within the pharmaceutical industry to develop modulators of the neuronal potassium conductance referred to as the M-current, because of its sensitivity to inhibitory modulation by a variety of G-protein coupled receptor ligands, most notably muscarinic acetylcholine receptor agonists148. This current was first identified in the late 1970’s and subsequently demonstrated to modulate synaptic plasticity and neuronal excitability in many areas of the brain121,148. The molecular nature of the M-current only became evident following the characterization of loss-of function mutations in a rare hereditary human epilepsy called benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC)149. Around the time of these studies, Wang and colleagues demonstrated for the first time that a heteromultimeric combination of KV7.2 and KV7.3 were the molecular components of at least one form of the neuronal M-current150. Subsequent studies have indicated that heteromultimeric combinations of KV7.3 and KV7.5 may also underlie M-currents in some areas of the brain151. The contribution of KV7.4 to the M-current is less clear although it is evident that KV7.4 is important in auditory physiology because of its expression in hair cells of the cochlea and loss-of-function mutations or SNPs associated with congenital deafness DFNA2 (deafness, autosomal dominant nonsyndromic sensorineural 2) and age-related hearing impairment152,153.

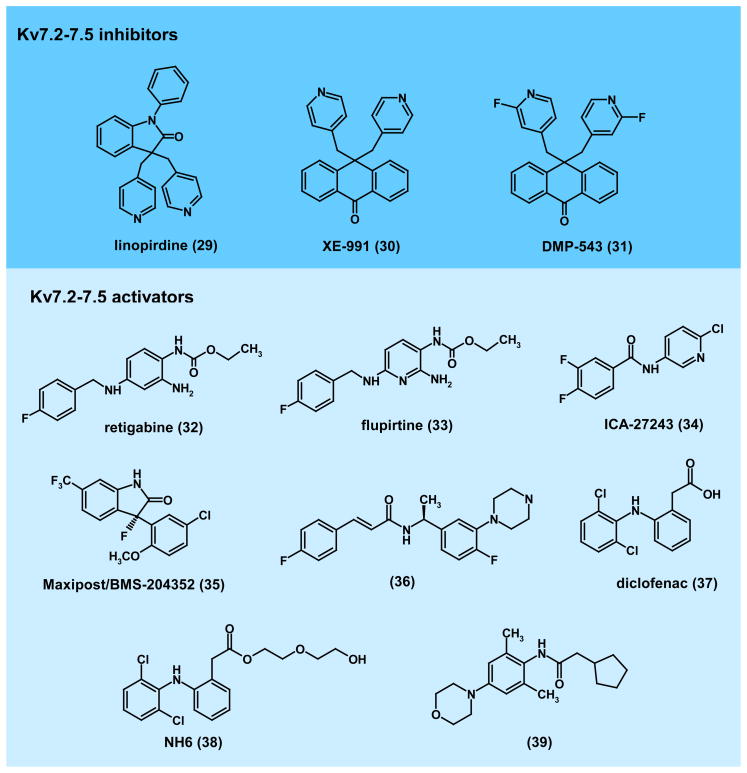

Given the importance of KV7.2–5 in a wide variety of neuronal processes it is perhaps not surprising that considerable effort has been directed towards developing therapeutic agents that target these channels. More than 20 patents for novel KV7.2–7.5 modulators have been issued and over 100 US patent applications are currently at various stages of approval. Early studies with M-current (KV7.x) inhibitors like linopirdine (29, Fig. 5) demonstrated improvements in learning and memory performance in animals154. However clinical trials only provided equivocal results for treating cognitive disorders155. While second generation inhibitors like XE-991 (30) and DMP-543 (31) were developed156, no further clinical efficacy studies investigating improvement of cognitive function have been reported.

Figure 5. Structures of KV7.2–7.5 channel modulators.

KV7.2–7.5 inhibitors:(29), linopridine154; (30), XE-991156; (31), DMP-543156. Kv7 channel activators had been proposed to improve learning an memory but failed in clinical trials. Kv7.2–7.5 activators: (32), retigabine (Valeant/GSK)157–159; (33), flupiritine173,174; (34), ICA-27243 (Icagen)165,166; (35), Maxiprost/BMS-204352170,178; (36), acrylaminde compound-24 (BMS)170,178; (37), diclofenac180; (38), NH6 (Tel-Aviv University)181; (39), 2-cyclopentyl-N-(2,6-dimethyl-4-morpholin-4-yl-phenyl)-acetamide (Lundbeck)185,186. KV7.2/7.3 activators are effective anticonvulsants in rodent models and clinical trials and have been proposed for the treatment of neuropathic pain, anxiety disorders, mania, migraine, ADHD and schizophrenia based on rodent data.

In contrast to the abandoned inhibitors, there remains widespread interest in the pharmaceutical industry to develop M-current activators. The first agent proven to enhance M-current activity was retigabine (32). Retigabine’s activation of recombinant KV7.2/KV7.3 was confirmed independently by a number of investigators, who demonstrated current enhancement by retigabine resulted from a profound hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage-dependence of channel activation157–159. When examined in vivo, retigabine exhibited anticonvulsant activity in a broad range of seizure models including PTZ, maximal electric shock, audiogenic seizures in DBA/2J mice as well as seizures produced by amygdala-kindling160. Based on these findings retigabine has been the subject of a number of clinical studies assessing its anticonvulsant activity in humans. Phase-II161,162 and more recently Phase-III efficacy trials163,164 have been successfully completed and retigabine is currently awaiting FDA approval as a new first-in-class epilepsy therapy.

A number of other pharmaceutical companies are at various stages in the development of KV7.2–7.5 activators. For example, Icagen Inc. has developed benzanilide KV7.2/7.3 openers, exemplified by ICA-27243 (34), which exhibits >30-fold selectivity for KV7.2/7.3 over KV7.3/7.5 heteromultimeric, or KV7.1, KV7.4 and KV7.5 homomultimeric channels165. Like retigabine, ICA-27243 shows efficacy in a variety of animal seizure models166 providing evidence that selective activation of KV7.2/7.3 is sufficient to achieve anticonvulsant activity. Despite the promising in vivo activity of ICA-27243 (and a more advanced related compound ICA-69673) in animal models, this class of agents has not been developed beyond Phase-I. However, Icagen is currently developing a new structurally distinct KV7.2/7.3 activator chemotype, exemplified by ICA-105665, which recently successfully completed Phase-I clinical trials167.

The clear role of KV7 channels in controlling neuronal excitability, combined with expression of KV7.x channels in sensory and central neurons involved in nociceptive signaling168,169, has further prompted the exploration of KV7.2–7.5 activators for the treatment of pain170,171. Both retigabine and its structural analog flupirtine (33) produce analgesic activity in rat models of neuropathic pain172–174. Flupirtine has been in clinical use as an analgesic in Europe since 1984 and is currently in Phase-II clinical trials in the United States for the treatment of fibromyalgia (press release from Pipex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). However, a recently completed Phase-IIa clinical trial of retigabine in patients with postherpetic neuralgia failed to demonstrate significant antinociceptive activity. Furthermore, the KV7.2/7.3 selective activator ICA-27243 has shown significant oral anti-nociceptive activity in animal models of inflammatory, chronic and neuropathic pain175,176, and a number of different KV7.2–7.5 activator chemotypes (35, 36) developed by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) have been reported to be effective in diabetic neuropathy and other rodent neuropathic pain models following intravenous administration170,177,178. BMS has also sought patent approval for the use of KV7.2–7.5 activators for the treatment of migraine pain179. Interestingly, diclofenac (37), an “old” non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug used clinically to treat inflammation and pain associated with arthritis, activates KV7.2 channels, as do a number of related compounds (i.e. meclofenamic acid)180. Structural analogs of diclofenac such as NH6 (38), which retain KV7.2 channel opening activity, but lack cyclooxygenase inhibitory activity, have recently been synthesized181 and may allow assessment of the contribution of KV7.x opening to the analgesic activity of this class of agents.

Both selective and non-selective KV7.2/7.3 activators further exhibit efficacy in animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders such as anxiety, ADHD, mania, bipolar disease and schizophrenia182. Investigators at Neurosearch A/S in Denmark have shown that retigabine and ICA-27243 but not the KV7.4/7.5 preferring activator BMS-204352 (Maxipost), are effective in an amphetamine and chlordiazepoxide induced hyperactivity model of mania183. Similar findings with retigabine were reported by researchers at Lundbeck A/S, who demonstrated in a conditioned avoidance response paradigm model of antipsychotic activity, that retigabine could inhibit avoidance responses, an effect blocked by the KV7.x inhibitor XE-991184. Furthermore, retigabine was able to inhibit hyper-locomotor responses in phencyclidine-sensitized animals, which is often considered as a disease model for schizophrenia184. Lundbeck has reproduced these findings with their own proprietary compounds (39)185,186.

While most of the interest in developing KV7.2–5 activators as therapeutic agents has focused on neurological or psychological disorders, the presence of these channels in bladder and other urologic tissues, in combination with the finding that KV7.2–7.5 activators can modulate bladder contraction and micturition responses in animal models, has resulted in speculation that these agents may also find utility in the treatment of incontinence and related disorders187.

KV10.1 (EAG1)

KV10.1 (EAG1) gives rise to a slowly activating, non-inactivating K+ current in heterologous systems. Abundant message12,188,189 and protein190 are found in the brain, but peripheral tissues show protein expression only in restricted cell populations188. Paradoxically, the only characterized physiological role of KV10.1 is in skeletal muscle development, where it is expressed during a limited time window when myoblasts exit the cell cycle and fuse191. Deletion of exon 1 in mice results in a mild increase in sensitivity to seizures, but no more severe phenotype (Menke, H, Dissertation 1998, University Göttingen). Most of the interest in KV10.1 stems from its expression in up to 70% of tumor cell lines and human cancers, such as colon carcinoma192,193 (where amplification of the gene has been detected by FISH in 3.5% cases and correlates with poor prognosis), gastric194 and mammary tumors188 and sarcomas195 (in some of which channel expression also correlates with a poor outcome). Efforts to determine the mechanism underlying this expression pattern have been largely unsuccessful, although it has been reported that KV10.1 expression is initiated after immortalization by papillomavirus oncogenes196. KV10.1 expression might offer an advantage to tumors through increased vascularization and resistance to hypoxia18. However, this does not explain the observation that the proliferation of cell lines, derived from all mentioned tumor types, is reduced by inhibition of the expression or function of KV10.1197. Additionally, KV10.1 expression appears to also affect cytoskeletal organization, which might influence proliferation and other properties of tumor cells such as migration and metastasis198.

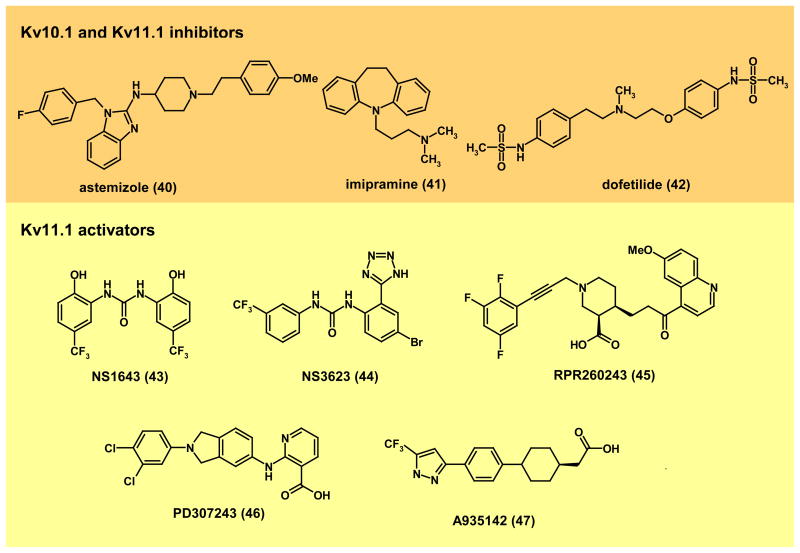

Two potent blockers of KV10.1, astemizole (40, Fig. 6) and imipramine (41) have been shown to decrease tumor cell proliferation in vitro, and, in the case of astemizole, also in vivo195,199–201. In mouse models, oral doses of astemizole well below the toxic range reduced the progression of established subcutaneous tumors (melanoma, pancreas and mammary carcinomas) and the frequency of metastasis in lung carcinoma models with a potency comparable to the maximal tolerable dose of the established chemotherapeutic agent cyclophosphamide18. As is always the case in oncology, only tests in humans will clarify the predictive value of these observations. Additionally, both imipramine and astemizole block also KV11.1 (hERG) and therefore pose cardiac risks (e.g. Ref.202); in fact, the antihistamine astemizole was withdrawn from the market in 2000 because of this risk. However, as we will describe below for KV11.1, the risk to benefit ratio for these drugs might need to be reconsidered for repositioning. The inner mouths of KV10.1 and KV11.1 are very similar, although not identical203. Nevertheless, all known KV10.1 blockers are also effective blockers of KV11.1 and therefore share their cardiac safety problems. This has prompted the search for biological modulators able to differentiate between the two channel classes. As of yet, no specific peptide toxin has been reported and only a monoclonal antibody (mAb56) specifically blocks KV10.1 without affecting KV11.1 or the close relative KV10.2204. The antibody showed efficacy in vitro against several tumor cell lines, and in vivo in certain tumor models, but the doses required were high, and the reduction of tumor growth was modest. The experiments were performed in immunodeficient mice, so that the antibody could in principle act exclusively as a channel blocker. Interestingly, the role of KV10.1 in tumor biology is not exclusively mediated by potassium permeation, since a non-conducting mutant still preserves part of the pro-neoplastic properties of the wild type channel18.

Figure 6. Modulators of KV10.1 and KV11.1.

Kv10.1 and Kv11.1 inhibitors:(40), astemizole199–202; (41), imipramine199; (42) dofetilide. Kv10.1 inhibitors have been proposed for the treatment of cancer9,179. KV11.1 (hERG) inhibitors prolong the QT interval and can be both antiarrythmic and proarrythmic (e.g. recall of the antihistamine astemizole). KV11.1 activators: (43) NS1643 (Neurosearch)208; (44) NS3623 (Neurosearch)209; (45), RPR260243 (Sanofi-Aventis)210; (46), PD307243 (GlaxoSmithKline)211; (47), A935143 (Abbott Laboratories)212. KV11.1 activators have been proposed as potential antiarrythmics205.

KV11.1 (hERG)

KV11.1 (hERG) plays a crucial role in cardiac repolarization (Fig. 4a), especially in the later phases of the action potential based on its unique kinetics. Upon depolarization, i.e. in the ascending phase of the action potential, KV11.1 opens rapidly, but potassium flux is quickly terminated by channel inactivation. Upon repolarization, release of inactivation is fast and is followed by slow deactivation. In this way, the channel is active during the depolarization of the action potential and during part of the diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle. In the later phase the potential is set at values where the driving force for potassium is very low, but potassium conductance buffers incoming depolarizations202,205. Thus, KV11.1 has a pivotal role in setting the duration of the effective refractory period. KV11.1 mutations cause Long QT syndrome (LQTS) type-2 because deficient KV11.1 function reduces repolarization and increases the possibility of torsade de pointes, ventricular fibrillation and sudden death24,206. The enormous interest of the pharmaceutical industry in KV11.1 is due to its involvement in drug-induced or acquired Long QT syndrome (aLQT). Kv11.1 blockers like dofetilide (42) have been used for many years as class III antiarrythmics207. This class of drugs is very efficacious in preventing and reverting atrial fibrillation and flutter, but their intrinsic arrhythmogenic activity largely restricts their use (often to stationary therapies). As mentioned earlier, KV11.1 can be blocked by a large variety of structurally diverse compounds and regulatory agencies request that all new drug candidates are tested for this possibility.

The large number of compounds identified as channel modulators has made it possible to identify several KV11.1 activators in recent years (Fig. 6). Of these, six are small molecules (NS1643208, NS3623209 (Neurosearch A/S) RPR260243210 (Sanofi-Aventis), PD307243211 (GlaxoSmithKline) and A935142212 (Abbott)), and one is a natural toxin (mallotoxin213). Due to its complex kinetics, the activity of KV11.1 can be increased by altering activation, inactivation, or deactivation, and all these properties are actually modified by the various KV11.1 activators. NS1643 (43) and NS3623 (44) reduce inactivation, RPR260243 (45) delays deactivation, while PD307243 (46) and A935142 (47) alter all three. These activators have two potential therapeutic applications: First, they could be used to rescue aLQT. Additionally, KV11.1 activators could become a novel class of anti-arrhythmics, since they have been reported to reduce electrical heterogeneity in the myocardium and thereby the possibility of re-entry205. However, a recently described cardiac condition exhibiting faster repolarization resulting in a shorter QT interval and therefore termed Short QT (SQTS)214, raises concerns about the feasibility of such an anti-arrhythmic approach although experimental models show that shortening of the QT interval appears to pose low risk of arrhythmia205.

Of the 300 different LQT-inducing mutations described in KV11.1, a large fraction results in defective channel trafficking215. Interestingly, KV11.1 blockers also increase surface expression. However, there is no direct relationship between channel blocking efficiency and trafficking increase, since compounds that do not block the channels, like thapsigargin or fexofenadine, also increase surface expression216. Compounds like these could directly improve membrane targeting of the channel by acting as molecular chaperones. It is therefore conceivable to use modifiers of Kv11.1 trafficking to ameliorate LQTs originating from surface expression defects of KV11.1217.

Besides its relevance in cardiac physiology, relative overexpression of a primate-specific, brain isoform of KV11.1 (KCNH2–3.1), which lacks an N-terminal domain crucial for slow deactivation and therefore induces high-frequency, non-adaptive firing patterns in cultured cortical neurons, has recently been linked to an increased risk of schizophrenia218. The authors of this study speculate that isoform-specific inhibitors might be useful for the treatment of schizophrenia. KV11.1 has also been extensively characterized in tumors219. As discussed for KV10.1, the expression of KV11.1 seems to be required for tumor cell proliferation, and KV11.1 blockers impair the proliferation of tumor cells. KV11.1 also interacts with integrins to regulate survival and migration, and is implicated in the regulation of apoptosis220–226. Thus, available data suggests KV11.1 as a target for cancer therapy, but the concomitant inhibition of IKr would initially seem a severe hurdle for such an approach. Several considerations should be made in this regard. Obviously, the risk/benefit profile of an antioncogenic drug is radically different from that of compounds for the treatment benign conditions. Additionally, there exist at least three alternative transcripts or KV11.1227,228, with different expression in the heart and in tumor cells, which opens the possibility to selectively inhibit the channel in tumors while preserving heart function, in a similar way as previously mentioned for schizophrenia.

Finally, it has been recently shown that an anticancer compound (the CDK inhibitor roscovitine), in phase-II clinical trials229 is actually an efficient blocker of KV11.1, but does not induce arrhythmia, probably due to its low affinity for the closed and inactivated states of the channel. However, KV11.1 inhibition could not only directly contribute to the prevention of tumor progression but might also treat some collateral effects of neoplasia. For example, KV11.1 expression is required for muscle wasting related to inactivity and neoplasia230 presumably through its role in the activation of massive ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation.

Outlook and challenges of KVchannel drug discovery

Since the cloning of the first KV channel more than 20 years ago, remarkable progress has been made in our understanding of the diverse physiological and pathophysiological roles of this class of channels. However, due to the difficulties of targeting ion channels in general, medicinal chemistry efforts in this area have considerably lagged behind drug development in the G-protein coupled receptor and the protein kinase field. KV channel drug discovery is of course plagued by the same general problems as all other target fields, namely that transgenic approaches can be misleading for target evaluation. Although heterozygous KV7.2+/− and KV7.2 transgenics, where channel expression was drastically reduced231,232, validated KV7.2 as a target for anticonvulsive therapy, many other transgenic approaches have been disappointing. The reasons for this can be multiple and range from developmental compensation to different physiological roles of a particular KV channels in different species. Striking examples of the later are the lack of importance of KV1.3 in mouse T cell function (see KV1.3 section) or the different roles of KV1.4, KV1.5, KV4.2 and KV4.3 in the cardiac action potential of different species233. Another aspect that has made KV channel drug discovery difficult is the fact that traditional methods developed for high-throughput screening of ion channels, such as binding assays or voltage-sensitive fluorescent probes, measure ion channel activity indirectly and thus can miss compounds that interact with a particular conformational (gating) state of the channel. Furthermore, these assays can be susceptible to potentially misleading actions of compounds with poor physiochemical properties (i.e. low solubility “sticky” hydrophobic compounds) that can result in the identification of false actives or can miss some truly active compounds [see Box 2 for an overview of screening technologies]. However, with the recent advent of high- or at least medium-throughput electrophysiology, which measures KV channel function directly and is able to identify state-dependent modulators, this situation is currently changing and pharmaceutical companies and academic screening centers are becoming increasingly successful at identifying potent and selective KVchannel modulators.

The discovery of K+ channel modulating drugs is also increasingly assisted by structural information. The X-ray structures of K+ channels in the open and closed states have revolutionized our knowledge about how drugs target K+ channels and although a co-crystal of the bacterial KcsA channel with tetrabutyl ammonium currently is the only visualized example of a ligand bound in the inner pore of a K+ channel, results of mutational, electrophysiological, and ligand-binding experiments are increasingly interpreted in structural terms using homology modeling and ligand docking. However, as impressive as this progress has been, true channel structure-based drug design is currently not possible for KV channel modulators and it is to be hoped that co-crystals for medically important channels such as KV1.5, KV7.2 or KV11.1 with drug molecules bound, will eventually be obtained. At present, it remains a challenge to decide which of the available structures to use for homology modeling since the inner-pore geometry varies substantially between the KcsA, KVAP and KV1.2 structures9. Other critical issues are the possible coexistence of multiple drug-binding modes and the general lack of concepts that include the influence of protein dynamics on high-affinity drug binding. Like all ion channels, KV channels are “moving targets” that undergo large conformational changes switching between open, closed and inactivated states on a millisecond time scale. These changes in “gating state” are often accompanied by drastic changes in the conformation of drug binding sites resulting in a phenomenon referred to as “state-dependent inhibition”. The possible “trapping” of the channel in one of its many possible conformations is at present impossible to model.

Based on the current status of the KV channel field, it is to be expected that drugs modulating the channels discussed here (KV1.1, KV1.3, KV1.5, KV7.2–7.5, KV10.1 and KV11.1) will reach the clinic within the next few years. Non-selective KV channel modulators like Fampridine (4-AP) may have already found a niche in the potential treatment of multiple sclerosis. The KV7.2/7.3 activator retigabine has completed phase-III clinical trials for the treatment of epilepsy and currently represents the most advanced novel KV channel modulator. Next generation modulators of KV7.2/7.3 channels are only a few years behind retigabine in their development. However, it is also sobering to contemplate, that despite more than 20 years of work no KV channel modulator specifically designed for a particular target has reached the market yet. Other KV channels like KV2.1 or KV3.4 may offer attractive therapeutic opportunities in the future, but need to be explored further before they can be regarded as valid drug targets. It will also be interesting to see whether any repositioning of existing marketed drugs will take place in the KV channel field. For example, could an “old” drug like clofazimine find new life as a Kv1.3 inhibitor-based immunosuppressant? Clearly, development of KV channel targeting drugs is at an early stage and certainly a challenging endeavor, but the opportunities for future success are extensive.

Acknowledgments

We thank Boris Zhorov for help with Figure 3. The authors’ work has been supported by the National Institute of Health (RO1 GM076063 to H.W.) and the Max-Planck Society (L.A.P).

Footnotes

Financial Interest Statement

H.W. is an inventor on the University of California patent claiming PAP-1 and related KV1.3 blockers for immunosuppression. She is a scientific founder of Airmid, a start-up company that is aiming to develop KV1.3 blockers as immunosuppressants. N.A.C. is an employee of Icagen Inc., a company that is currently developing KV7.2 and KV7.3 activators for epilepsy. L.A.P. is a shareholder of iOnGen AG, a company developing ion channel-based diagnostics and therapies in oncology.

Contributor Information

Heike Wulff, Email: hwulff@ucdavis.edu.

Neil A. Castle, Email: ncastle@icagen.com.

Luis A. Pardo, Email: Pardo@em.mpg.de.

References

- 1.Harmar AJ, et al. IUPHAR-DB: the IUPHAR database of G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D680–685. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]