Abstract

This letter describes a general method for the preparation of carbohydrate coated gold nanoparticles. The generality of this method has been demonstrated by surface coating AuNPs with the following sugars: glucose (monosaccharide); sucrose, maltose, or lactose (disaccharides); raffinose (trisaccharide); and starch (polysaccharide). The non-toxic, water-soluble phosphino aminoacid P(CH2NHCH(CH3-)COOH)3, THPAL, has been used as a reducing agent in this process. The sizes of sugar coated AuNPs that have been generated in this study are: 30 ± 8 nm (Glucose), 10 ± 6 nm (sucrose), 8 ± 2 nm (maltose), 3 ± 1 nm (lactose), 6 ± 2 nm (raffinose), and 39 ± 9 nm (starch).

INTRODUCTION

Nanoparticles have gained prominence as ideal synthetic building blocks in bottom-up approaches for constructing a plethora of nanomaterials.1–5 “Nuts and bolts” for constructing new and useful nanomaterials include nanoparticles of uniform size, shape, and capping ligands. Among all, capping ligands play a vital role in transforming the spherical or triangular shaped nanoparticles to nanodevices or nanosensors of any desired shape. 6–18 Much of the recent research efforts have focused on developing new strategies to fabricate nanoconstructs with carbohydrates6,7 as capping ligands because of their potential applications in the design and development of nanoscale devices and nanosensors for biomedical applications.8–18 Carbohydrates contain many hydroxyl and carbonyl groups; these groups offer sugar coated nanoparticle a unique H-bonding capabilities in constructing supramolecular architecture. Upon surface coating with nanoparticles they provide attractive nano construction abilities for building smart nanomaterials. For example, nanowires of platinum or tellurium have been constructed from glucose stabilized platinum nanoparticles or starch stabilized tellurium nanoparticles.19,20 Despite large number of applications, there are only very few reports on direct generation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) in a glucose or a starch matrix. Current strategies for carbohydrate functionalization of gold nanoparticles utilize thiol tailored sugars as synthons.10,12 However, a unified non-thiol synthetic approach applicable for all carbohydrates in functionalizing gold nanoparticles would be highly useful for constructing nanomaterials. Wallen and coworkers have developed a “green” method to synthesize and stabilize silver nanoparticles in starch matrix using glucose as the reducing agent.21,22 Recently, Roberts and co-workers have reported the synthesis and stabilization of β-D-glucose capped AuNPs using sodium borohydride as reducing agent.23 Conventional synthetic strategies (e.g., reduction via citrate) for the production of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) do not yield desirable results when applied toward the production of sugar coated AuNPs. Therefore, development of novel synthetic methods for synthesizing carbohydrate capped nanoparticles is imperative for achieving innovative advances in the field of nanomaterials. Indeed, generation of carbohydrate coated AuNPs, using one general method is still a major challenge. As part of our on going research efforts on the design and development of new functional materials for biomedical applications,24–29 we, herein, report an efficient generalized synthetic methodology for the synthesis of library of carbohydrate coated AuNPs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

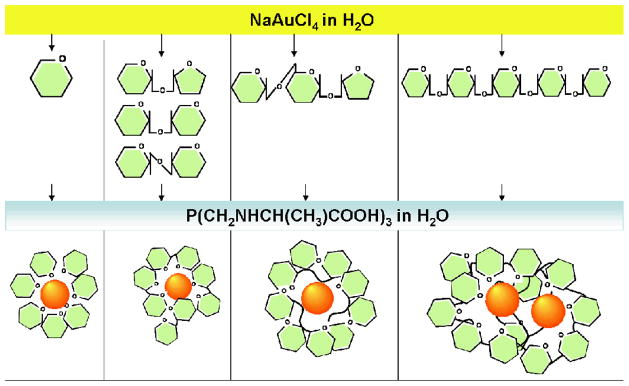

This universal approach involves direct mixing of carbohydrates of choice with nanoparticle precursor in the presence of P(CH2NHCH(CH3)COOH)3 (THPAL)24 as a reducing agent. This generalized strategy has several unique advantages: (i) the nanoparticle fabrication process is comprehensive; gold nanoparticles can be generated under biofriendly conditions in any given carbohydrate matrix. No thiol molecules are used either in the production or in the stabilization steps, (ii) it utilizes a novel water-soluble, non-toxic, phosphino amino acid, P(CH2NHCH(CH3)COOH)3 (THPAL), as the reducing agent. THPAL has been found to be non-toxic in pigs at 50–100 mg/Kg of body weight, (iii) it involves onestep generation of gold nanoparticles coated with sugar molecules. Overall, the general strategy described here can be easily employed to generate nanoparticles in any given sugar motifs with minor or no procedural modifications. The stabilization of carbohydrate capped AuNPs is mediated by a “macromolecular crowding” technique. The term macromolecular crowding in cellular biology refers to conditions where molecules occupy 40% of the physical volume. Macromolecular crowding process has been shown to affect many molecular and physical processes.28 In a similar fashion, our new process makes use of simple sugars to occupy ~40 % of the total aqueous volume. This imposed physical constraint secludes nanoparticles from each other thus, preventing aggregation.

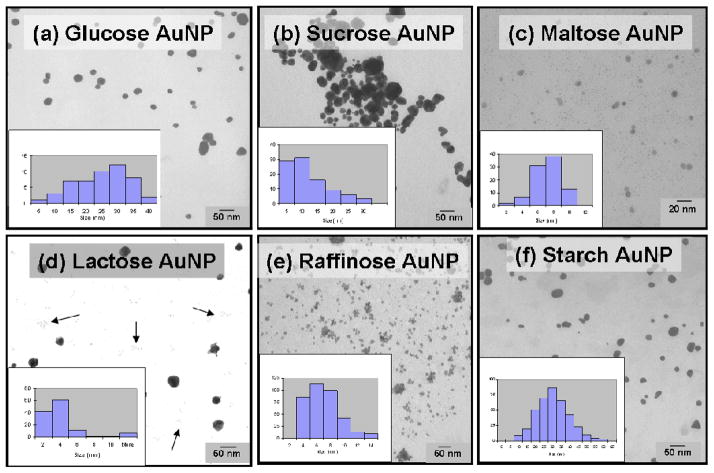

Our new process for the generation of gold nanoparticles is shown in Scheme 1. In a typical synthesis, a 100 μL of 0.1 M aqueous solution of NaAuCl4 was added to 6 mL of a 0.4 % of starch aqueous solution. The reaction mixture was stirred and heated to 80°C for one minute for complete dissolution of starch. To this mixture, 20 μL of 0.1M aqueous solution of reducing agent, P(CH2-NHCH(CH3)COOH)3 (THPAL), was added. Immediately after the addition of the reducing agent (THPAL), the color of the reaction mixture changed from yellow to a ruby red. The color change indicates the formation of nanoparticles. The surface plasmon absorption maximum (λmax) for starch stabilized AuNPs is 546 nm. This absorption maximum is characteristic of nanoparticulate stabilization in carbohydrate matrices. TEM image and size distribution histogram of starch coated nanoparticles is shown in Figure 1. The average size of starch stabilized AuNPs is 39 nm with the standard deviation of 9 nm.

Scheme 1.

General synthetic strategy for sugar coated AuNPs

Figure 1.

TEM images and particle size histograms of sugar coated AuNPs.

To test the generality and the overall efficiency of our new strategy, a library of carbohydrates including, monosaccharide (glucose), disaccharide (sucrose, maltose, lactose), trisaccharide (raffinose), or polysaccharide (starch) were selected. Hydrogen bonding networks present in carbohydrates provide many hydrophilic cavities for the facile generation of AuNPs. The protocol described for the synthesis of starch coated AuNPs, was followed to generate AuNPs in different carbohydrate matrices with good efficiency (Table 1). The size and particle size distribution of AuNPs directly depends on the nature of sugars used to stabilize them. AuNPs stabilized in lactose are smaller in size with a diameter of 3 nm (± 1 nm). On other hand, AuNPs stabilized in a starch matrix are bigger in size with a diameter of 39 nm (± 9 nm). The kinetics of nanoparticle generation in carbohydrate matrix was mainly dominated by phosphine and aminoacid groups present in THPAL. It is plausible that aldehydic group present in simple reducing sugars (e.g. glucose) will assist in the nanoparticle generation process. However, application of reducing sugars alone to generate nanoparticles in various carbohydrate matrices did not yield fruitful results. In addition, trisaccharides and polysaccharides did not undergo any reduction in the absence of THPAL. It is reasonable to infer that AuNP formation in simple sugars is assisted synergistically by the phosphine and reducing sugars, whereas, AuNPs in higher saccharides utilize only THPAL for the formation of uniformly sized particles. It is important to note here that the strategy reported here obeys “green chemistry” conditions. The reaction process is “biofriendly;” water is used as the solvent, and the starting materials and reducing agent are all non-toxic.

Table 1.

Reaction conditions for the generation and stabilzation of carbohydrate capped AuNPs.

| Carbohydrate | Concentration of carbohydrate | Amount of Reducing agent (THPAL, 0.1 M) used | Reaction Time (min) | Size of nanoparticles (nm) | λmax (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 2.38 M | 10 | 2 | 30 ± 8 | 535 |

| Sucrose | 1.25 M | 10 | 3 | 10 ± 6 | 535 |

| Maltose | 1.19 M | 10 | 3 | 8 ± 2 | 540 |

| Lactose | 1.18 M | 10 | 5 | 3 ± 1 | 540 |

| Raffinose | 0.72 M | 10 | 5 | 6 ± 2 | 540 |

| Starch | 0.4% | 20 | 5 | 39 ± 9 | 546 |

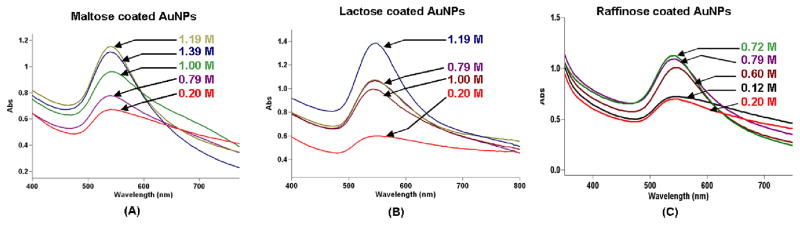

The stabilities of AuNPs toward aggregation depends on the concentration of sugar molecules present near the nanoparticles. In order to find out the optimum carbohydrate concentrations necessary to generate and stabilize AuNPs, a systematic investigation was carried out. In this investigation, AuNPs were generated in solutions with varying concentrations of carbohydrate and the plasmon absorption bands were examined by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Figure 2). For example, AuNPs were generated in different molar solutions of maltose (Figure 2(A)). AuNPs generated under lower concentration of maltose exhibited a broad and weak plasmon absorption band, characteristic of inhomogeneity due to aggregation of particles. The spontaneous aggregation of AuNPs may be attributed to lower concentration of carbohydrate matrix. Recent work by Qi et al29 have shown that disaccharide such as sucrose could not reduce HAuCl4 to generate gold nanoparticles. As the concentration of carbohydrate increases there is a significant decrease in the aggregation. At 1.19 M concentration of maltose relatively uniform size gold nanoparticles with less degree of aggregation were generated. Similar investigations were performed in other carbohydrates to find the optimum concentration necessary for generating and stabilizing AuNPs (Figures 2(B) and 2(C)). It is interesting to note that the concentrations of carbohydrates required for generating and stabilizing AuNPs, decreases from monosaccharide to polysaccharide. Nanoparticles generated inside the concentrated carbohydrate solution, provides a crowded environment thus, they are expected to have little surface interaction between them. Indeed, this molecular crowding provides an attractive environment for preventing AuNPs from aggregating. It is important to recognize that the concentrations of carbohydrates in the reactions are ~40% w/v, which satisfies the condition followed in “macromolecular crowding” process. The stability study results show that glucose-AuNPs possess least stability, whereas, other carbohydrates are generally stable for longer than 5 hours. Starch stabilized nanoparticles possess extraordinary stability. The stability of starch-AuNPs can be explained as follows: the core structure of polymeric starch molecules contains hydrogen bonded amylopectin rings which are capable of folding around the nanoparticles and thus, are expected to prevent the aggregation of AuNPs.

Figure 2.

UV-Vis spectra of AuNPs generated under different concentrations of carbohydrates.

In conclusion, a novel, one-step, general synthetic methodology for the generation of sugar-coated gold nanoparticles with sizes from 3 nm to 39 nm was developed. Different sizes of the AuNPs obtained by using different sugars, provides a library of AuNPs for constructing supramolecular nanoparticle assemblies. This general method provides new chemical, catalytic and biomedical application opportunities to previously inaccessible realm of sugar coated Gold nanoparticles.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute grant on Cancer Nanotechnology Platform No: 1R01CA119412-01.

References

- 1.Shevchenko EV, Talapin DV, Kotov NA, O’Brien S, Murray CB. Nature. 2006;439:55–59. doi: 10.1038/nature04414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Zhuang J, Peng Q, Li YD. Nature. 2005;437:121–124. doi: 10.1038/nature03968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Portney NG, Singh K, Chaudhary S, Destito G, Schneemann A, Manchester M, Ozkan M. Langmuir. 2005;21:2098–2103. doi: 10.1021/la047525f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maye MM, Lim IIS, Luo J, Rab Z, Rabinovich D, Liu TB, Zhong CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1519–1529. doi: 10.1021/ja044408y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chane-Ching JY, Cobo F, Aubert D, Harvey HG, Airiau M, Corma A. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:979–987. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BS, Hong DJ, Bae J, Lee M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16333–16337. doi: 10.1021/ja055999a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrientos AG, de la Fuente JM, Rojas TC, Fernandez A, Penades S. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:1909–1921. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rojas TC, de la Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Penades S, Ponsonnet L, Fernandez A. Adv Mater. 2002;14:585–588. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrientos AG, de la Fuente JM, Rojas TC, Fernandez A, Penades S. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:1909–1921. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds AJ, Haines AH, Russell DA. Langmuir. 2006;22:1156–1163. doi: 10.1021/la052261y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halkes KM, Carvalho de Souza A, Elizabeth C, Maliaars P, Gerwig GJ, Kamerling JP. Eur J Org Chem. 2005:3650–3659. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De la Fuente JM, Eaton P, Barrientos AG, Menendez M, Penades S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6192–6197. doi: 10.1021/ja0431354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de la Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Rojas TC, Rojo J, Canada J, Fernandez A, Penades S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:2258–2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ipe BI, Yoosaf K, Thomas KG. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1907–1913. doi: 10.1021/ja054347j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez JM, Josephson L, Weissleder R. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:261–264. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinti L, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Nano Lett. 2006;6:488–490. doi: 10.1021/nl0524694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds AJ, Haines AH, Russell DA. Langmuir. 2006;22:1156–1163. doi: 10.1021/la052261y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de la Fuente JM, Penades S. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:636–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu QY, Gao F, Komarneni S. Langmuir. 2005;21:6002–6005. doi: 10.1021/la050594p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu JC, Raveendran P, Qin GW, Ikushima Y. Chem Commun. 2005:2972. doi: 10.1039/b502342d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raveendran P, Fu J, Wallen SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13940–13941. doi: 10.1021/ja029267j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raveendran P, Fu J, Wallen SL. Green Chemistry. 2006;8:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu JC, Anand M, Roberts CB. Langmuir. 2006;22:3964–3971. doi: 10.1021/la060450q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghuraman K, Katti KK, Barbour LJ, Pillarsetty N, Barnes CL, Katti KV. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6955–6961. doi: 10.1021/ja034682c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillarsetty N, Raghuraman K, Barnes CL, Katti KV. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:331–336. doi: 10.1021/ja047238y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghuraman K, Pillarsetty N, Volkert WA, Barnes C, Jurisson S, Katti KV. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7276–7277. doi: 10.1021/ja025987e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Boote EJ, Neal S, Srinath A, Kannan R, Katti KV. Molecular Imaging. 2004;3:235. [Google Scholar]; (b) Katti KV, Kattumuri V, Chandrasekar M, Srinath A, Kannan R, Katti KK, Bhaskaran S, Pandrapragada RK. Molecular Imaging. 2004;3:278. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minh DDL, Chang C–en, Trylka J, Tozzini V, McCammon JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6006–6007. doi: 10.1021/ja060483s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]