Abstract

This article describes results from the Oregon Latino Youth Survey, which was designed to identify factors that promoted or hindered academic success for Latino middle- and high-school youngsters. The study samples included a total of 564 Latino and non-Latino students and parents. Analyses showed that Latino students reported a high frequency of discriminatory experiences and institutional barriers at school, and that they and their parents were more likely to experience institutional barriers compared to non-Latinos. Further, Latino students and parents reported that they/their youngsters were more likely to dropout of school compared to non-Latinos. Path models showed lower acculturation and more institutional barriers were related to less academic success for Latino students. More parent academic encouragement and staff extracurricular encouragement were associated with better academic outcomes for Latino students. Finally, family socioeconomic disadvantage had an indirect effect on Latino youngster academic success, through effects on parent monitoring and school involvement.

Keywords: Latino youth, acculturation, parenting, school dropout, youth academic functioning

School success is among the most important correlates of overall physical, mental, and social well-being. In fact, academic functioning is known to be highly related to a host of other important outcomes for youth including substance use, delinquency, and associations with deviant peers (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Loeber & Dishion, 1983). Students who dropout from school experience lower income, greater unemployment, are significantly overrepresented in the adult corrections population, and are more likely to require social services during their lifetimes compared to high school graduates (Rumberger & Larson, 1994; Secada et al., 1998).

For Latinos, such findings are extremely troubling because of the large number of population members that may be impacted by continuing failure in the academic domain. The Latino population is the largest and most rapidly growing ethnic subgroup group in the U.S., growing at a rate of about 4.5 times the rate for the rest of the population between 1990 and 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). Given this context, it is not surprising that many school systems around the country are not prepared to address the needs of an increasingly culturally pluralistic student population. As a result, Latinos continue to be overrepresented in samples of families at risk for poor behavioral and mental health outcomes (Chavez & Roney, 1990; Vega et al., 1998; Vega & Rumbaut, 1991), and Latino students evidence school dropout rates of about 2 to 3.5 times the rate for white non-Latino students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000). Moreover, as the Latino student population continues to increase concurrent with tightening state and federal education budgets, this situation can only get worse. Information is clearly needed on what factors increase and decrease risk for Latino student academic failure. Further, in order to strengthen intervention approaches designed to improve outcomes for Latino students, we need more studies that identify risk and protective factors that are both malleable and proximal to academic outcomes.

In this paper, we describe the results of the Latino Youth Survey (LYS), a cross-sectional study focusing on the predictors of academic success for Latino and non-Latino middle- and high-school aged youngsters. The LYS was carried out through an intensive community effort to explore the factors that promoted and hindered school success for Latino youth and was embedded as part of a larger Latino youth mentoring project. Comparative analyses of survey data provided an opportunity to describe potential differences between Latino and non-Latino youngsters’ and parents’ experiences of the school environment. Structural equation modeling was used to test an integrative theoretical framework that specifies some of the relevant mechanisms involved in the pathway towards academic success for Latino youth, and how the contextual factor of acculturative stress impacts academic success.

Etiology of School Failure

School failure is not a random act. Rather, it is the consequence of a host of interacting influences that can set children on a trajectory towards a lifetime of difficulties. The exact causes of dropping out are complex and not well understood, but it is clear that individual factors that lead to dropping out for Latinos are similar to those for other groups; low achievement, dissatisfaction with school, a need to begin work early, and (for girls) early pregnancy all contribute to dropping out (Fashola & Slavin, 1997). At the group level, high poverty, language issues, and recent immigration status have been shown to relate to higher dropout rates for Latinos. Yet even with such variables controlled, Latinos still evidence higher dropout rates than their non-Latino peers (Rumberger, 1995; Secada et al., 1998). Thus, Latino students face a greater risk of dropping out than other students regardless of their position in society.

While conceptual models articulating the pathways towards school failure for Latinos are sparse, social interaction learning theory is one widely replicated developmental model that delineates how risk and protective factors influences adolescent problem behaviors including school failure (see Reid, Patterson, & Snyder, 2002). Within a social interaction learning framework, family members and peers are presumed to influence each other’s behavior in a bidirectional shaping process (e.g., parent to child and child to parent). Parent-child and peer-child interactions are hypothesized to directly shape child and adolescent adjustment. In contrast, contextual factors (e.g., SES, family structure transitions, parental adjustment, neighborhood, marital adjustment, and social support) are thought to exert their effects on youth adjustment indirectly, most notably through their effects on parenting practices. If one or more negative contexts or life experiences impinge on a family, multiple aspects of parenting practices can suffer and the adjustment of children and adolescents can be negatively affected. Thus, according to this model, the effects of contextual factors on youngsters’ negative adjustment (e.g., school failure) are hypothesized to occur indirectly, through their impact on parenting practices.

A variety of studies have been conducted that support aspects of the social interaction learning model for mostly non-Latino samples. For example, there is considerable evidence that parenting practices are a proximal focal point in the etiology of early- to mid-adolescence problem behaviors, including school failure (Dishion, Capaldi, & Yoerger, 1999; Dishion & Loeber, 1985), particularly in terms of mediating the impact of contextual factors on those behaviors. More specifically, in several studies coercive discipline practices mediated the relationship between parental stress and negative youth antisocial behavior (Conger, Patterson, & Ge, 1995; Forgatch, Patterson, & Ray, 1996; Patterson, 1986). Similarly, lax monitoring, coercive discipline, and poor problem solving have been found to mediate the relationship between parental psychopathology (e.g., antisocial qualities, depression) and youth antisocial behavior (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1997; Patterson & Dishion, 1985).

More recently, we conducted two studies that tested the mediation of social context effects on youth adjustment by parenting practices. Both studies employed the Oregon Divorce Study sample of divorcing mothers and their sons (Grades 1 to 3). The first study showed that the effect of mothers’ education on child academic achievement was mediated by parent academic skill building (DeGarmo, Forgatch, & Martinez, 1999). The second study showed that the effect of family structure transitions on child behavioral, emotional, and academic adjustment was mediated by positive and coercive parenting factors (Martinez & Forgatch, 2002).

Expanding the Model for the Latino Population: The Role of Acculturation

Although the social interaction learning model has not been thoroughly researched for generalizability to Latino groups, a variety of studies have shown that family and parenting factors predict academic and related problems for Latino youngsters. For example, Dumka, Roosa, and Jackson (1997) showed that immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican American mothers’ greater acculturation predicted more consistent discipline, which in turn predicted less depression and conduct problems among their fourth-grade children. Vega, Gil, Warheit, Zimmerman, and Apospori (1993) used self-report data to show that family and parenting protective factors (i.e., respect, pride, cohesion, parental support) contributed to a decreased disposition to deviance for Cuban American adolescents, controlling for psychosocial and acculturation variables. Similarly, Apospori, Vega, Zimmerman, Warheit, and Gil (1995) found that high family pride and support buffered the relationship between deviance and later drug use for Latino adolescent boys.

In another study, Gil, Wagner, and Vega (2000) examined the longitudinal relationships between acculturation (i.e., language use, nativity), acculturation strain, familism, parental respect, and later disposition to deviance and alcohol involvement. Using structural equations modeling, they found that for both U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinos, greater acculturation was associated with more language conflicts and acculturative stress. Acculturative stress was associated with lower familism and parental respect. Familism at the beginning of the study predicted lower disposition to deviance one year later. Greater parental respect also predicted less disposition to deviance for U.S.-born Latino adolescents, which was associated with less alcohol involvement one year later. Taken together, these findings underscore that parenting factors are important proximal predictors of Latino youth outcome. Factors such as acculturation are clearly important as well, but these are likely to operate as distal influences on youth adjustment, mediated through parenting.

Acculturation is a multidimensional construct that describes phenomena resulting from continuous contact between groups of individuals from different cultures and subsequent changes in the cultural patterns of one or both groups (Berry, 1998). Because acculturation is multidimensional, including such factors as language proficiency, language use, nativity, cultural-related behavioral preferences, and ethnic identity, no consistent or uniform definition or measurement strategy has been used in the literature (Cabassa, 2003; Escobar & Vega, 2000; Rogler, Cortes, & Malgady, 1991). In the United States, most acculturation researchers have assumed that increments of involvement in the American host culture entail corresponding decrements of involvement in traditional culture. However, some researchers have argued the need to abandon this assumption and assess “Latinoness,” “Americanism,” and “biculturalism” separately (Szapocznik, Kurtines, & Fernandez, 1980).

In an attempt to empirically summarize the body of research on Latino acculturation, Rogler et al. (1991) conducted a review of studies examining the linkage between acculturation and mental health status in Latino samples. Although lack of measurement uniformity made formal quantitative meta-analysis impossible, the authors cited numerous studies that found both linear positive and linear negative relationships between acculturation and psychological distress, and other studies that showed a curvilinear relationship with biculturalism associated with better mental health. Such divergence suggests that linear theories about acculturation effects are insufficient to account for the process of adjustment (Gil, Vega, & Dimas, 1994). Moreover, acculturation itself is a marker variable for other psychosocial processes (e.g., ethnic identity processes, experience of structural barriers) that should be measured as potential explicating variables that link acculturation with family outcomes (Escobar & Vega, 2000). Despite such equivocal findings about the directions of relationships between acculturation and outcomes for youth, greater levels of acculturation have been shown to predict increased risk for substance use, psychological distress, psychiatric illness, and delinquent behavior (Amaro, Whitaker, Coffman, & Heeren, 1990; Ortega, Rosenheck, Alegria, & Desai, 2000; Vega et al., 1993).

While greater levels of acculturation may relate to higher risk for social, psychological, and emotional difficulties for some Latino children, the role of acculturation in predicting academic outcomes is less understood. For many children, greater and more rapid acculturation to the norms of mainstream school environments may promote greater success at school (Kao & Tienda, 1995). This may be particularly true in school systems that do not support a multicultural curriculum focus and/or have limited support for non-English speakers. Research linking acculturation with school success for Latino youngsters has shown that factors such as recent immigration and limited English proficiency increase the risk of dropping out for Latino students (Rumberger, 1995). For example, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000), the dropout rate for Latino youth born outside the U.S. (44.2%) was more than double the dropout rate for first-generation (14.6%) and second-generation (15.9%) Latino youth.

Research Questions

The major goals of this paper are two-fold. First, we describe key factors in the school experiences of Latino middle and high school students and parents, and contrast those experiences with the reported experiences of non-Latino students and parents. Second, we present models based on our culturally informed extension of social interaction learning theory that examine predictors of academic success and dropout likelihood for Latino students.

Method

Project Background

The process that led to the LYS was initiated in 1998 after a group of community members met to discuss the needs of Latino youth in Lane County, Oregon schools. Ultimately, more than 20 community representatives and professionals from the local education system, social services agencies, and governmental organizations, formed an advisory group. In 1999, the advisory group acquired local funding to develop a student-directed Latino youth mentoring program. More than 20 students received stipends during that summer to develop a survey for Latino youth and parents intended to inform the community at large about the experiences of Latinos in Oregon schools. Specifically, the project goals were to (1) identify positive aspects of Latino student experiences and activities, (2) identify opportunities to address unmet needs, and (3) create a coalition comprising parents, youth, service providers, and community leaders designed to help address the needs of Latino youth.

Student interns selected for the program were local Latino high school students. The group received formal and informal training on the scientific process, survey research methods, and literature searching and reviewing. Prominent community professionals from schools, social services, university, and juvenile justice settings provided mentoring. Latino and non-Latino parent and youth versions of the survey were developed, piloted, and administered during the following academic year to youth in grades 7 through 12. A separate survey was also administered to the parents of middle and high school youth.

In the summer of 2000, leaders in the Latino community and scientists from the Oregon Social Learning Center (OSLC) began a collaboration to mentor a second group of Latino students in data analysis, interpretation, and presentation. All participants had been program members during the summer of 1999. In addition to developing further skills in social science research methods, interns acquired new skills in computing and grass roots organizing. The summer’s 10-week training program culminated in a formal student presentation of survey results to leaders in the Latino community, politicians, law enforcement personnel, school officials, social scientists, social services providers, and student families.

Survey Participants

Data were collected from three different samples. The first sample of 314 youth participants was drawn from four school districts in Lane County, Oregon. The second sample of 116 participants was drawn from student attendees of the Oregon State Latino Youth Summit sponsored by the Oregon Commission on Hispanic Affairs. The third sample comprised 130 parents from Lane County, Oregon who agreed to complete the survey or to be interviewed. Participating parents were not necessarily those whose children completed the youth survey. Youth participants were enrolled in school between the sixth and twelfth grades. In order to protect privacy, no identifying data were collected from participants such as name, age, or gender.

Ethnicity

Participants were classified as “Latino” or “non-Latino.” For the youth surveys, youth were classified as Latino or non-Latino by official school records and teacher and staff reports (i.e., the “knowledgeable other” method; Foster & Martinez, 1995). We also examined the level of agreement between this classification method and students’ self-identification of their ethnic backgrounds. For the Lane County youth data, 162 participants were classified as “Hispanic/Latino.” Of those, most (74%) self-identified as Latino. The remaining 26% self-identified as belonging to another racial/ethnic group (7%) or as multiracial (14%) or they did not answer the question (5%). An additional 152 Lane County youngsters were classified as “non-Latino.” Of those, most (69%) self-identified as European/White. An additional 21% of youngsters classified as non-Latino self-identified as belonging to other ethnic groups (including about 6% who identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino). The remaining non-Latino youngsters indicated that they were either multiracial (7%), or did not answer the question. In contrast, all youngsters attending the Oregon State Latino Youth Summit were classified as “Latino.” Most students (62%) self-identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino. However, an additional 7% self-identified as belonging to another racial/ethnic group, and a relatively large group of youngsters (31%) did not answer the question.

For the parent surveys, parents self-identified as Latino or non-Latino. Specifically, 73 participants (56%) self-identified and were classified as “Hispanic/Latino.” Fifty-one participants (39%) identified as belonging to a different racial/ethnic group or were multiracial. These participants were classified as “non-Latino.” Of those participants classified as non-Latino, most (74%) self-identified as European/White. Ethnic self-identification data were missing for six participants (5%) and were therefore excluded from comparative analyses.

While participants were not specifically asked to provide country of origin information, local sociodemographic data indicate that about 78% of Latino families in Oregon trace their family roots to Mexico, with most of the remaining 22% tracing their roots to other countries in Central and South America (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

Other Demographic Characteristics

Most parents (79%) indicated that they were employed at the time of the survey. Five percent were not presently working outside the home, 12% were full-time homemakers, 2% indicated that they were full-time students, and 2% did not answer. Fifty-four percent indicated that they were born outside the U.S. Most (88%) of these participants were in the Latino parent group.

Survey Description and Data Collection Procedures

Approximately 494 consent forms were mailed to Latino families and 370 consent forms were mailed to non-Latino families in Lane County seeking parental consent for their and/or their youngster’s participation. Approximately, 33% of Latino parents and 41% of non-Latino parents consented for their youngster to participate. Furthermore, 23% of Latino parents and 15% of non-Latino parents agreed to participate. Since the Latino state student survey was administered during a statewide gathering of students, and a prior consent was not required, the participation rate for the Oregon state Latino sample was quite high (i.e., greater than 90%).

In the Lane County youth sample, surveys were administered to groups of students in classrooms. In the Oregon state youth survey, participating students completed the survey in a large group during the Latino Youth Summit. In all administrations, project personnel were present during data collection to answer questions. Survey completion was anonymous; no student names or identifying information was requested. The youth survey included 46 questions, with additional sub-questions. Individual survey items included Likert-type, forced choice, and open-ended questions. Various items assessed respondents’ satisfaction with school, involvement in school, discriminatory and unwelcoming school experiences, school performance (e.g., grades, types of classes taken, etc.), language/acculturation levels, parenting factors, social support availability, and demographic characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, employment status, nativity, parent education, etc.).

For the parent sample, surveys were administered via telephone interviews. The parent survey was similar to the youth version, consisting of 45 items assessing parents’ satisfaction and involvement in their youngsters’ school, knowledge about school programs and personnel, welcoming-ness of school environment, parenting practices, homework participation, youngster school performance, and demographic characteristics (e.g., parent employment status, family income, parent ethnicity, etc.).

Both versions of the survey were available in English and Spanish. Copies of the surveys are available from the first author.

Analytic Strategy

Statistical results from student and parent datasets are presented in three forms: (1) comparisons of average scores between the three Latino and non-Latino student groups on the central study variables using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc pair wise tests (Bonferroni tests), (2) comparisons of average scores between only two groups at a time (e.g., those between state and county Latino students and those between Latino and non-Latino parents) using independent sample t-tests, and (3) structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate theoretical process models.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and statistically significant group difference tests of all major study variables are presented in Table 1 for the student datasets and in Table 2 for the parent dataset. Outcome variables were organized in both tables by three conceptual domains represented in the theoretical model: (1) social and acculturation contexts, (2) parenting practices, and (3) youngster adjustment. Significant pair wise comparisons between groups are presented in the far right columns of the tables and were reported if groups were significantly different from one another at the p < .05 to p < .001 levels. If no significant differences were detected between any two groups on any study variable an “n.s.” notation was used.

Table 1.

Latino and Non-Latino Youth Descriptive Data and Contrasts

| Latino State | Latino County | Non-Latino | Significant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | County (C) | Contrasts | ||

| Variable | Range | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | (p < .05) |

| Social/Acculturation Contexts | |||||

| Born in the U.S. | 0–1 | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.97 (0.16) | C > B > A |

| Years Living in the U.S. | 0–17 | 7.14 (4.01) | 6.63 (4.61) | ----- | n.s. |

| English Proficiency | 1–3 | 1.44 (0.66) | 2.48 (0.67) | 2.88 (0.35) | C > B > A |

| English Use at Home | 1–3 | 1.77 (0.57) | 2.01 (0.77) | 2.92 (0.27) | C > B > A |

| Discrimination for Being | |||||

| Latino | 0–2 | 0.66 (0.75) | 0.61 (0.72) | ----- | n.s. |

| Barriers to Participation | 1–5 | 3.15 (0.83) | 2.57 (0.78) | 2.39 (0.67) | A > B > C |

| Available Spanish | |||||

| Resources | 1–3 | 1.87 (0.57) | 2.10 (0.55) | ----- | B > A |

| Available Social Support | 0–60 | 18.06 (11.47) | 15.83 (10.47) | 22.63 (11.64) | C > A, B |

| Insularity/No Support | 0–10 | 3.41 (2.79) | 1.61 (2.41) | 0.89 (1.72) | A > B > C |

| Mother’s Education | 1–11 | 4.04 (2.35) | 6.96 (3.30) | 7.78 (1.88) | C > B > A |

| Father’s Education | 1–11 | 4.23 (2.78) | 7.57 (3.33) | 8.25 (1.96) | B, C > A |

| Persons Living in Home | 1–13 | 5.15 (1.63) | 5.24 (1.93) | 4.55 (1.85) | B > C |

| Student is Employed | 0–1 | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.66 (0.47) | B, C > A |

| Hours Working Per | |||||

| Week (Job 1) | 0–43 | 16.38 (11.60) | 10.42 (11.63) | 7.89 (7.88) | A > B, C |

| Parenting Practices | |||||

| Extracurricular | |||||

| Encouragement | 0–6 | 3.33 (1.98) | 2.92 (1.70) | 3.09 (1.58) | n.s. |

| Parents Help with | |||||

| Homework | 1–5 | 2.22 (1.24) | 2.37 (1.31) | 2.63 (1.39) | n.s |

| Parent Academic | |||||

| Encouragement | 1–4 | 2.76 (0.83) | 3.26 (0.61) | 3.38 (0.53) | C > B > A |

| Comfort Talking with | |||||

| Parents | 1–4 | 2.67 (1.03) | 2.97 (0.82) | 3.07 (0.76) | B, C > A |

| Have Serious Talks | |||||

| with Parents | 1–5 | 3.34 (1.53) | 3.30 (1.38) | 3.20 (1.35) | n.s. |

| Parents Know Friends | 1–5 | 3.27 (1.28) | 2.95 (1.18) | 3.41 (1.04) | C > B |

| Youngster Adjustment | |||||

| Likelihood of Dropping | |||||

| Out | 1–4 | 1.53 (0.90) | 1.53 (0.91) | 1.15 (0.48) | A, B > C |

| Grade Point Average | 1–7 | 4.32 (1.50) | 4.62 (1.44) | 5.31 (1.21) | C > A, B |

| School Satisfaction | 1–5 | 3.24 (0.99) | 3.48 (0.99) | 3.76 (0.74) | C > A, B |

| Log of Discipline | |||||

| Problems | −.69–2.60 | 0.89 (0.56) | 0.37 (0.83) | 0.15 (0.95) | A > B, C |

| Homework Completion | |||||

| Rate | 1–5 | 2.90 (1.02) | 2.77 (0.86) | 2.91 (0.71) | n.s. |

| Have Gang Contact | 0–1 | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.52 (0.50) | 0.34 (0.47) | A > B > C |

Table 2.

Latino and Non-Latino Parent Descriptive Data and Contrasts

| Latino | Non-Latino | Significant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County (A) | County (B) | Contrasts | ||

| Variable | Range | M (SD) | M (SD) | (p > .05) |

| Social/Acculturation Contexts | ||||

| Born in the U.S. | 0–1 | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.80 (0.40) | B > A |

| Years in the U.S. (foreign born) | 0–47 | 11.46 (9.09) | ----- | ----- |

| English Proficiency | 1–5 | 3.07 (1.46) | 4.84 (0.62) | B > A |

| Difficulty Helping With | ||||

| Homework | 1–4 | 2.60 (1.07) | 1.71 (0.72) | A > B |

| Barriers to School Participation | 1–5 | 3.14 (0.94) | 2.25 (0.87) | A > B |

| Unwelcoming School | ||||

| Experiences | 0–4 | 1.99 (1.03) | 1.63 (1.15) | A > Ba |

| Discomfort Contacting School | 1–3 | 1.60 (0.78) | 1.35 (0.46) | A > B |

| Know How to Contact School | 1–3 | 1.48 (1.36) | 2.59 (0.98) | B > A |

| Persons Living in House | 2–8 | 5.22 (1.51) | 4.08 (1.23) | A > B |

| Per Capita Yearly Income | ||||

| (x1000) | 1.6–35.0 | 5.87 (5.84) | 13.53 (7.48) | B > A |

| Parenting Practices | ||||

| Parent Academic | ||||

| Encouragement | 0–2 | 1.44 (0.69) | 1.37 (0.72) | n.s. |

| Monitoring | −3.40–1.33 | −0.15 (1.15) | 0.30 (0.66) | B > A |

| Participation in School | ||||

| Events | 0–4 | 1.70 (1.11) | 2.10 (1.04) | B > A |

| Volunteer at School | 0–4 | 0.45 (0.91) | 0.47 (0.78) | n.s. |

| Uninformed About School | ||||

| Resources | 1–4 | 1.87 (0.78) | 1.98 (0.71) | n.s. |

| Contact with School Staff | 1–4 | 1.91 (0.81) | 2.06 (0.75) | n.s. |

| Help with Homework | 1–5 | 2.40 (1.44) | 23.36 (1.30) | n.s. |

| Youngster Adjustment | ||||

| Likelihood of Dropping Out | 1–4 | 1.69 (0.87) | 1.34 (0.69) | A > B |

| Grade Point Average | 1–4 | 3.18 (0.64) | 3.17 (0.89) | n.s. |

| Discipline Problems | 0–1 | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.20 (0.40) | n.s. |

| Homework Completion Rate | 1–5 | 4.33 (0.86) | 4.04 (1.40) | n.s. |

| Have Gang Contact | 0–1 | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.19 (0.39) | n.s. |

This difference was marginally significant (p = .07).

Social and Acculturation Contexts

In terms of nativity status, many more non-Latinos were born in the U.S. compared to Latinos. For youngsters, the vast majority of non-Latinos (97%) reported being born in the U.S., while much fewer county (51%) and state (35%) Latino students indicated they had been born in the U.S. Similarly, 80% of non-Latino parents reported being U.S. born, while only 26% of Latino parents were born in the U.S. Of the Latino parents who were foreign born, most (58%) had been in the U.S. for 10 years or less. In terms of English proficiency, Latino students and parents reported less English proficiency than non-Latinos, and state Latino students were less proficient in English than county Latino students. Using an estimate of income based on responses from parents, Latino parents were estimated to have significantly less per capita yearly income (i.e., yearly dollars per person living in the household) than non-Latino parents.

About 50% of Latino students reported having experienced discrimination for being Latino or observed this type of discrimination occurring to someone else. Both Latino student groups reported experiencing more barriers to participation in school activities (e.g., not receiving information, not having time because of work, prohibitive fees, not feeling comfortable around school people) than non-Latino students. Latino parents also reported more barriers to their participation in their children’s school than non-Latino parents. Latino parents reported having had somewhat more unwelcoming experiences at their children’s school than non-Latino parents. While there were no significant differences between Latinos and non-Latinos in terms of the frequency of parents helping with homework, Latino parents reported having more difficulty helping with homework. Latino youngsters reported less availability of social support (i.e., having people to talk to about serious life issues) than non-Latino youngsters.

Parenting Practices

County Latino and non-Latino students reported higher levels of parent academic skill encouragement (e.g., rewarding good grades, giving consequences for school failure) than state Latino students, but there were no differences between Latino and non-Latino parent report of academic skill encouragement. Non-Latino parents reported greater monitoring and supervision of their children (e.g., having serious talks with them, knowing their friends, and knowing whether they hang out with deviant peers) than Latino parents.

Youth Adjustment

Although Latino and non-Latino parents did not differ in their report of their youngster’s grade point average (GPA), both county and state Latino students reported having worse grades than non-Latino students. Although no group indicated they were particularly likely to drop out, both groups of Latino students reported being more likely to drop out than non-Latino students. Similarly, Latino parents reported that their youngsters were more likely to drop out than non-Latino parents. While no differences emerged between Latino and non-Latino parents in terms of their report of their youngsters having contact with gang members, more Latino students from the state and county reported having gang contact (e.g., knowing someone who is in a gang, having a good friend who is in a gang) than non-Latino students.

Predicting School Success

In order to advance our understanding of the processes and experiences of Latino students and parents, and to provide some initial tests of our conceptual frame, we conducted a series of path models with data from Latino students and parents. Data from the state and county Latino students were combined for this analysis. There were two main outcome variables measuring the student’s school success -- the student’s GPA and how likely it was he or she would drop out of school. The predictor factors were based on variables measuring the students’ and parents’ social and acculturation contexts, and parenting practices. Two models were examined utilizing Latino youth data, and one model was examined utilizing Latino parent data.

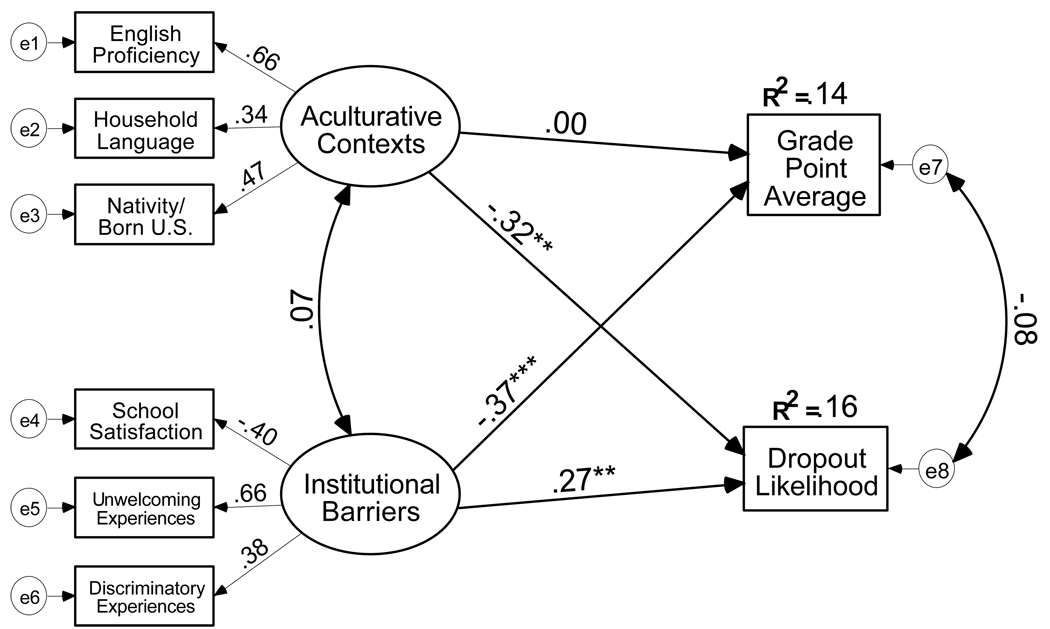

The first model examined the role of acculturation factors and institutional barriers in predicting Latino students’ school success. Results of the first model are shown in Figure 1 with standardized path coefficients. The overall model demonstrated good fit to the data [χ2 (16) = 23.36, p = .10] with a comparative fit index of .99. Results from this model indicated that greater student acculturation (modeled as a latent construct of U.S. nativity, English proficiency, and English use at home) predicted lower likelihood of dropout (β = −.32) but was not significantly related to student reported GPA (β = .00). On the other hand, greater institutional barriers (measured by discriminatory experiences, school satisfaction, and unwelcoming experiences) significantly predicted both lower GPA (β = −.37) and greater likelihood of dropping out of school (β = .27), controlling for students acculturation level.

Figure 1.

Institutional barriers and acculturative contexts predicting Latino students’ school success. χ2(16) = 23.36, ρ = .10, n = 278, CFI = .99, *ρ < .05, **ρ < .01, ***ρ < .001.

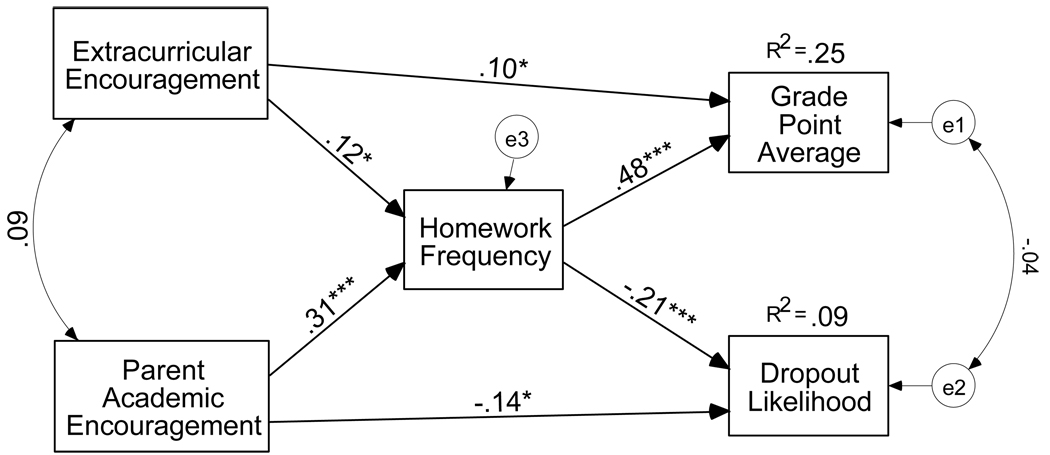

The second model focused on the role of academic encouragement by staff at school and by parents in the home, and the resultant path model demonstrated good fit to the data [χ2 (2) = .13, p = .86, CFI = 1.00]. This model indicated that academic encouragement experienced at school, academic encouragement received by parents, and homework all significantly predicted a student’s school success. Results of the academic encouragement model are presented in Figure 2. Starting at the left side of the model, both staff extracurricular encouragement and parent academic encouragement predicted frequency of homework completed by the student (β = .12 and β = .31, respectively). As expected, greater frequency of completing homework was related to higher GPA (β = .48) and less likelihood of dropping out (β = −.21). Not only did greater school and parental encouragement predict greater school success through homework, but more staff encouragement also had a direct association with a higher GPA (β = .10) and parental encouragement had a direct association with staying in school (β = −.14). The fact that encouragement experienced at school was correlated with encouragement at home coupled with the fact that these two variables predict school success underscores the potential importance of positive parent-school relationships for Latino students.

Figure 2.

School and parental academic encouragement predicting Latino students’ school success. χ2(2) = .13, ρ = .86, n = 278, CFI = 1.00, *ρ < .05, **ρ < .01, ***ρ < .001.

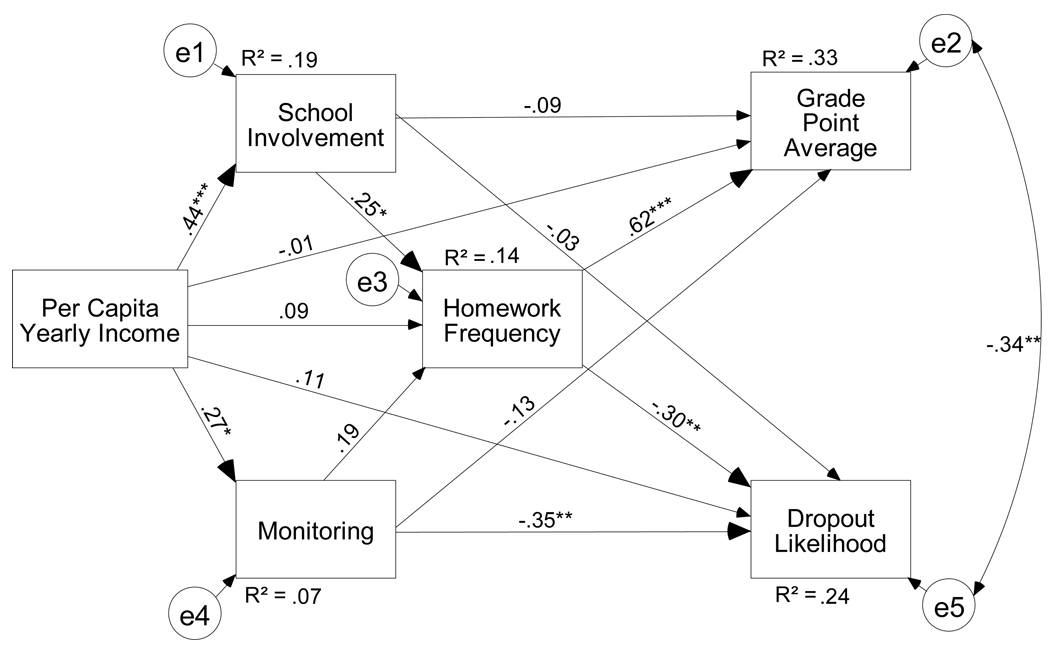

The final model was tested with data from Latino parents and examined the relationships between social contexts (i.e., per capita income in this case), parenting practices (i.e., monitoring, school involvement), and youth academic success. The model demonstrated adequate fit to the data [χ2 (1) = .86, p = .35, CFI = 1.00], and is shown in Figure 3. Higher per capita income was associated with greater parent school involvement (β = .44) and more monitoring (β = .27). Greater parent school involvement predicted greater student homework completion frequency (β = .25), which predicted a higher GPA (β = .62), and lower likelihood of dropout (β = −.30). More parental monitoring was associated with lower likelihood of dropout (β = −.35). Consistent with our theoretical perspective, per capita income did not have direct effects on youngster academic success.

Figure 3.

Per capita income predicting parenting factors and Latino students’ school success. χ2(1) = .86, ρ = .35, n = 73, CFI = 1.00, *ρ < .05, **ρ < .01, ***ρ < .001.

Discussion

While it is clear that many Latino students face difficulties succeeding at school, little is known about the specific factors that promote and hinder success for these students. Findings from the LYS dataset shed light on school factors that differentiated Latino and non-Latino students, and show how these factors relate to academic success for Latino students. Comparative findings showed that Latino students experience an unacceptably high rate of institutional barriers (e.g., discrimination, low access to staff resources) that can impede their progress at school. Latino students and parents also reported experiencing more barriers to their participation at school than did non-Latino students and parents. While Latino students did not indicate they were particularly likely to drop out of school, they reported being more likely to do so than their non-Latino peers. Similarly, Latino parents also reported that their youngsters were more likely to drop out than did non-Latino parents.

For the prediction models, data collected on student acculturation, institutional barriers, and academic encouragement (particularly by parents) were important predictors of school success for Latinos. Higher levels of academic and institutional barriers, measured by discriminatory experiences and satisfaction with school resources, translated to lower likelihood of successful grades and projected likelihood of staying in school. On the other hand, the data showed that academic encouragement by parents and extracurricular encouragement by school staff served as a key protective factor promoting school success for Latino youth.

Finally, in the face of difficult life circumstances such as low socioeconomic status, these data showed that parents and family played a particularly important role in protecting Latino youngsters from experiencing the negative consequences of these events. For example, academic encouragement and being able to talk to parents about important life issues, along with school support led to greater student homework completion frequency. Frequency of homework, as expected, promoted greater school success.

Findings from the present survey identify a number of structural barriers that may have a substantial influence on school success and failure of Latino students. Difficult social and culturally specific life circumstances such as low income, experiences of discrimination, and feeling unwelcome at school represent significant challenges to Latino student school success. Moreover, Latino students are more likely to experience such structural barriers than their non-Latino peers.

These findings also demonstrate some of the complexity in understanding the impact of acculturation processes on outcomes for youngsters. The literature is replete with findings that show that greater levels of acculturation are related to worse adjustment outcomes (e.g., substance use, delinquency, deviant peer association) for Latino youngsters. The findings presented here suggested the opposite — higher levels of acculturation predicted better school outcomes. We think this finding may be a product of the cultural inflexibility of the educational system compared to other social systems. In situations where a system is not flexible enough to accommodate a pluralistic and culturally heterogeneous student population, students learn that they must assimilate quickly to the demands of the system in order to succeed. One can imagine this being a particularly difficult course to steer for Latino youngsters, especially when the same push towards greater acculturation levels may enhance their risk for poor outcomes in other domains.

These findings suggest that such complex and inflexible systems must change to promote academic success for all children. Teachers and administrators must be better equipped to deal with children in their increasingly diverse classrooms. They must be accountable for achieving goals set by their districts and communities for increasing their expertise in diversity. Educators must also have access to culturally inclusive curriculum materials and be willing to adapt standard materials when such multicultural curriculum is unavailable.

At an individual level, dealing with structural barriers in educational institutions may be complicated by insufficient coping strategies for adolescent minorities, especially ones that are founded on help-seeking, network-building, and social support (Stanton-Salazar, 2001). Invisible to most school officials, social estrangement of adolescents and lack of trust and confidence in significant others and in key school agents result in a lack of a help-seeking initiative and overall resignation to unsponsored self-reliance. For example, in a large multi-sample study of Latino students, interviews with adolescents showed how a lack of confianza (trust) inhibited youth to engage in help-seeking behaviors among teachers, and even for academic support from parents and peers (Stanton-Salazar, 2001).

Furthermore, outwardly raging adolescents who openly express their subjective alienation in attention-getting ways were more the exception than the norm among Latino students. Stanton-Salazar's (2001) extensive network analyses indicated that about half of Latino students' relations with school personnel were socially organized in ways that obstructed the formation of supportive relations and active help-seeking behavior. Feelings such as quiet shame, confusion, and powerlessness are the accompanying sentiments of many low-status adolescents, and were often masked by youthful bravado or stoicism. Such cognitive orientations toward school and authority figures are often associated with individual and collective efforts to demonstrate contempt for the surrounding forces of social stratification. These feelings can be aggravated by adolescents' attempts to "decode the system" and thereby demystify the many challenges lower status minority students face (Stanton-Salazar, 2001).

Stanton-Salazar's data also indicated that while resilient Latino students demonstrated good rapport and supportive relations with one or two teachers, the evidence also suggested that most adolescents were not embedded in a tightly knit and coordinated web of teachers, counselors, and staff. Therefore, institutional mediations or family- and community-based cultural strategies operate principally as a buffer against the full burden of class and racial stratification that is pervasive in the dominant cultural of education and social policy (Stanton-Salazar, 2001). What is needed are more systematic efforts that integrate family, community, and school efforts that foster social skills and problem solving styles, network-building, role-modeling, advocacy, and mobilization of resources across multiple sites (Stanton-Salazar, Vasquez, & Mehan, 2000).

While we think systems must change to address structural barriers for Latino students, we also recognize that such changes are very slow to development and may be even more distal to student academic success. These findings implicate Latino parents and family as being essential to and perhaps more proximal to student outcomes. Familia is the most powerful protective force for many Latino children. We need to develop and refine intervention strategies that enhance parents' abilities to promote success for their children. Such strategies need to be developed in partnership with communities and schools.

Limitations and Strengths of the LYS Dataset

The LYS dataset has some important limitations and strengths that must be considered in interpreting the results. The first limitation concerns the ethnic group classification method used in the survey. As discussed above, all participants were classified as “Latino” or “non-Latino” for the present paper. Parent self-report was used to classify parents as Latino or non-Latino. Ethnic group classification of youth data was based on a knowledgeable other method. Although there was significant agreement between youth self-report and the knowledgeable other classification, some disagreement was also observed. As noted in Foster and Martinez (1995), child ethnic self-identification and knowledgeable other classification methods have distinct advantages and disadvantages. For example, children’s ability to self-identify correctly may be hampered by the use of unfamiliar labels or by lack of representation of a particular label on the list (Bernal, Knight, Garza, Ocampo, & Cota, 1990; Foster & Martinez, 1995). Similarly, school officials or records may not be able to provide accurate classifications, especially for individuals who are bicultural (Foster & Martinez, 1995).

Classification of youngsters as non-Latino also presents an important methodological issue especially because this classification was used as the comparison group in this paper. While many of the non-Latino individuals self-identified as European/White, others self-identified as belonging to non-Latino ethnic minority groups or indicated they were biracial. We strongly encourage readers of this report to interpret the results cautiously in light of these complexities and the great heterogeneity of the groups described in this report.

A second limitation concerns the sample and data collection methods. Neither the youth nor the parent sample can be considered random samples taken from the population of Latino youth in Lane County, and thus may be biased in some unknown way. Further, only one method of data collection was used, the questionnaire. Questionnaire responses may be biased in certain ways, and this may affect the validity of the results. The use of other techniques, such as independent observations, may yield different results. Finally, responses were only obtained from students and parents. Their perceptions may be quite different than that of teachers, administrators, and other informed persons.

Although there are clear limitations to the data, we think these data advance the literature in a number of key ways. First and foremost, to date, there has been a dearth of studies that provide a glimpse into potential social and family processes connected to the development of academic problems among Latino youngsters. Second, these data give voice to students who have previously had little voice in shaping school policy and prevention efforts. Third, the samples utilized for the present study are relatively large, increasing the potential external validity of the findings.

Furthermore, there were several methodological advantages to the research design chosen for this survey. First, there were three subgroups of Latinos sampled in different ways (e.g., parents, county students, and state students). It is unlikely that there were systematic unknown biases operating in the same manner for each sub-group of Latino participants. Therefore, any similarities in process models of school adjustment are likely to reflect true cultural experiences for Latinos in the local community and the state. Second, the study focus is on Latino experiences. The inclusion of similar measures for a comparison group of non-Latino students provides an additional source of validating cultural experiences. Finally, the study capitalizes on multiple sources of data that include structured items with ordinal scaling plus open-ended qualitative questions in both English and Spanish that could only be answered from the perspective of the participants themselves.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by Grant No. R21 DA 14617 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, U.S. PHS, and Grant No. P30 MH46690 from the Prevention Research Branch, NIMH, U.S. PHS. Support for the mentoring project, survey development, and data collection was provided by a grant from the Lane Workforce Partnership, Lane County, Oregon. The authors would like to thank Carmen Urbina and her staff at Centro LatinoAmericano for their many contributions to this project, and the Latino Youth Project students for their hard work developing and administering the survey and for their enthusiasm and inspiration.

Biographies

Charles R. Martinez, Jr., Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist and research scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center in Eugene and directs the Oregon Prevention Research Center’s Latino Research Team. He is the principal investigator on the NIDA-funded Latino Youth and Family Empowerment (LYFE) Project, an intervention development and efficacy study for Latino families with youngsters at risk of substance use. His clinical and research interests center largely on identifying factors that promote healthy adjustment of families and children following stressful life events (such as changes in family structure, socioeconomic status, physical and/or emotional health, and immigration status), taking into consideration the cultural contexts in which families operate. He is interested in developing prevention theory and intervention models for multicultural relevance. When not pondering research and clinical problems, he enjoys spending time with family, playing guitar, running, and flying airplanes.

David S. DeGarmo (de Martinez), Ph.D., is a family sociologist at the Oregon Social Learning Center. His focus is on interactional processes and family adjustment as they relate to child development and within the context of preventive interventions. His theoretical interests include linkages between behavioral processes and larger social contexts such as social support networks, social class, and ethnicity. Currently, he is principal investigator of a 4-year representative study of divorced father families funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Beyond work, he enjoys friends, softball, home improvement projects, and the daily continuing education provided by his children.

J. Mark Eddy, Ph.D., is an Associate Director and a Research Scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center. He is an investigator on several long-term follow-up studies of preventive and clinical interventions conducted within the juvenile justice and the school systems. For the past four years, he has been working closely with the Oregon Department of Corrections on the development of a research-based parenting program for incarcerated mothers and fathers, and currently is studying the outcomes of the program. Dr. Eddy spends his free time playing, hiking, and running with his wife and children.

References

- Amaro H, Whitaker R, Coffman G, Heeren T. Acculturation and marijuana and cocaine use: Findings from HHANES 1982–84. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80 Supplement:54–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apospori EA, Vega WA, Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, Gil AG. A longitudinal study of the conditional effects of deviant behavior on drug use among three racial/ethnic groups of adolescents. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Drugs, crime, and other deviant adaptations: Longitudinal studies. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal ME, Knight GP, Garza CA, Ocampo KA, Cota MK. The development of ethnic identity in Mexican-American children. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation and health: Theory and research. In: Kazarian SS, Evans DR, editors. Cultural clinical psychology: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez JM, Roney CE. Psychological factors affecting the mental health status of Mexican American adolescents. In: Stiffman AR, Davis LE, editors. Ethnic issues in adolescent mental health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Patterson GR, Ge X. It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents' stress on adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1995;66:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS, Martinez CR., Jr Parenting of divorced mothers as a link between social status and boys' academic outcomes: Unpacking the effects of SES. Child Development. 1999;70(5):1231–1245. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi DM, Yoerger K. Middle childhood antecedents to progression in male adolescent substance use: An ecological analysis of risk and protection. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Loeber R. Adolescent marijuana and alcohol use: The role of parents and peers revisited. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11(1–2):11–25. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mothers' parenting, and children's adjustment in low-income, Mexican immigrant, and Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Vega WA. Mental health and immigration's AAAs: Where are we and where do we go from here? Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2000;188(11):736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fashola OS, Slavin RE. Effective dropout prevention and college attendance programs for Latino students. 1997 (Unpublished manuscript prepared for the Hispanic Dropout Project) [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, DeGarmo DS. Adult problem solving: Contributor to parenting and child outcomes in divorced families. Social Development. 1997;6(2):238–254. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, Ray JA. Divorce and boys' adjustment problems: Two paths with a single model. In: Hetherington EM, Blechman EA, editors. Stress, coping, and resiliency in children and families. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 67–105. [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Martinez CR., Jr Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24(2):214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA, Dimas JM. Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology. 1994;22:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Tienda M. Optimism and Achievement: The educational Performance of Immigrant Youth. Social Sciences Quarterly. 1995;76(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Dishion TJ. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;94(1):68–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Jr, Forgatch MS. Adjusting to Change: Linking Family Structure Transitions With Parenting and Boys' Adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(2):107–117. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Dropout rates in the United States:1999. Washington, DC: Office of Educational research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Rosenheck R, Alegria M, Desai RA. Acculturation and the lifetime risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanics. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2000;188(11):728–735. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Performance models for antisocial boys. American Psychologist. 1986;41:432–444. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ. Contributions of families and peers to delinquency. Criminology. 1985;23(1):63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J. The Oregon model: Understanding and altering the delinquency trajectory. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogler LH, Cortes DE, Malgady RG. Acculturation and mental health status among Hispanics: Convergence and new directions for research. American Psychologist. 1991;46(6):585–597. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW. Dropping out of middle school: A multilevel analysis of students and schools. Review of Educational Research. 1995;32:583–625. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW, Larson KA. Keeping high-risk Chicano students in school: Lessons from a Los Angeles Middle School dropout prevention program. In: Rossi RJ, editor. Schools and Students at Risk: Context and Framework for Positive Change. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University; 1994. pp. 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Secada WG, Chavez-Chavez R, Garcia E, Munoz C, Oakes J, Santiago-Santiago I, et al. No More Excuses: The Final Report of the Hispanic Dropout Project. Washington, D. C: U.S. Department of Education; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar RD. Manufacturing hope and despair: The school and kin support networks of U.S.-Mexican youth. New York: Teachers College Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar RD, Vasquez O, Mehan H. Reengineering success through institutional support. In: Gregory ST, editor. The academic achievement of minority students: Comparative perspectives, practices, and prescriptions. Lanham: MD: University Press of America; 2000. pp. 213–247. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Fernandez T. Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1980;4:353–365. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Washington D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; Census 2000. 2000

- U.S. Census Bureau. Washington D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief. 2001

- Vega WA, Gil AG, Warheit GJ, Zimmerman RS, Apospori EA. Acculturation and delinquent behavior among Cuban American adolescents: Toward an empirical model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21(1):113–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00938210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Rumbaut RG. Ethnic minorities and mental health. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:351–383. [Google Scholar]