Abstract

This article describes a women’s entrepreneurship exchange program that was designed and facilitated with the cooperation of various governmental and nongovernmental entities in Ghana for Ghanaian women. The article briefly reviews the entrepreneurship development literature from an international perspective and discusses the Entrepreneurship Program as a targeted approach for empowering and sustaining women’s economic situation in Ghana. Emphasis is placed on understanding the impact of cultural and social networks and the women’s ability to succeed as entrepreneurs through the use of social work skills.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, women, Ghana, eco-map, economic development, empowerment

INTRODUCTION

Since the industrial revolution, Africa has been one of the slowest growing and poorest economic regions in the world (Bloom, Sachs, Collier, & Udry, 1998). The number of people working in extreme poverty in Africa will increase by 20% by 2015 (Somavia, 2007). In sub-Saharan Africa, 55% of the population lives on less than $1 a day and 80% on less than $2 a day (Somavia, 2007). With this level of economic stagnant, entrepreneurship has been revered as one solution to improving economic conditions (Nieman, 2001).

According to Glewwe and Jacoby (1994) self-employment is extremely pervasive and rapidly growing within this region of the world. It is estimated that the number of individuals involved in small market enterprises and entrepreneurship in Africa is nearly twice as great as those working in large businesses (Frese, 2000). Most of the entrepreneurial activity could be an important link to economic growth for the individual and the community (Wennekers & Thurik, 1999). As political and economic climates continue to stabilize in most African nations, it is expected that entrepreneurship will blossom significantly as a part of poverty alleviation plans to maintain a level of cohesive economic stability and growth (McCarty & Attafuah, 2004). In fact, many African nations have made small business development a priority for diminishing high unemployment and poverty rates through formalized governmental entities for supporting the creation of various businesses among women and men (Nieman, 2001).

The increased awareness of women’s economic conditions around the globe has played a role in understanding family poverty. The study and development of entrepreneurship, particularly for women, has been a significant research agenda for many scholars over the past few decades (Moore, 1990). A worldwide movement has witnessed a significant increase in women working as entrepreneurs as a means for increasing their economic stability and that of their families (Bowen & Hisrich, 1986; Scherer, Brodzinski, & Wiebe, 1990).

This article presents an Entrepreneurship Training Program that was designed specifically for Ghanaian women as a tool for building economic stability and decreasing family poverty. The program is discussed in view of the international literature on women and entrepreneurship development and a description of the training program design is provided. The article discusses the training in helping women to understand the impact that cultural and social network systems have on their ability to succeed through the use of social work practice skills as a part of the training design.

STRUCTURAL BARRIERS IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT FOR WOMEN

According to Naffziger, Hornsby, and Kuratko (1994), the decision for women to seek entrepreneurship includes personal characteristics, the family and societal environment, personal goals, and the existence of business ideas while noting probable positive economic outcomes. Furthermore, women have noted that they lack the necessary work experience and financial stability that have countered financial instability that further compromised their business start-up ability (Shabbir & Di Gregorio, 1996). These barriers are fairly similar to those found in studies looking at women entrepreneurship development in South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Ghana.

In South Africa, a study assessing the needs of South African female entrepreneurs, found that women had historically incurred problems with finance and legal status as they attempted to start and sustain businesses (O’Neill & Viljoen, 2001). The study also found that women experienced difficulty with overcoming a nonexistent or limited business track record as proof of their ability to develop and sustain profitable businesses. In addition to these constraints, women also struggled with family commitments as they tried to balance new work life and family demands. Study participants noted that training programs should include train-the-trainer training, and be skills-based and sector-focused to increase participant success. Finally, participants thought that each program should provide links to mentor services and financial institutions as well as account for the specific needs of women in the community (O’Neill & Viljoen, 2001).

Like the information from South Africa, literature on entrepreneur-ship in Zimbabwe suggests that women face significant cultural stigma in relationship to wage earning (Chitsike, 2000). Traditionally, in Zimbabwe, women are not permitted to earn large sums of money. If they do earn, women are culturally encouraged to hide their success and claim it as a result of their husband or father. Structural barriers in Zimbabwe include inability to travel for business due to family constraints, lack of land assets, and limited marketable skills. The study also revealed that emphasis on education, while addressing illiteracy, is essential in allowing women to successfully pursue entrepreneurship (Chitsike, 2000). Interviews with Nigerian businesswomen revealed that their greatest challenge was being taken seriously by men within the business sector (Woldie & Adersua, 2004). This makes it difficult for women to expand and sustain businesses as they seek to collaborate and expand their ideas that create business growth successfully at various levels. Overwhelmingly, findings from these studies reflect women’s desire to gain control of their working lives as the largest benefit of becoming successful entrepreneurs in Nigeria (Woldie & Adersua, 2004). In Ghana, like a number of the aforementioned countries, women are entering into the workforce at a higher rate. Recent studies suggest that an increased number of female-headed households are evidenced in Ghana, despite rising rates of women living in poverty (Lloyd & Gage-Brandon, 1993). Thus, it is important to consider the increasing need to include women in business and entrepreneurship. Despite this apparent need, present day Ghanaian female entrepreneurs experience significant cultural challenges (Saffu & Manu, in press). First, the ascribed cultural status given to women within the community makes it difficult for them to succeed. For example, men appear to have greater access to education than women (Fallon, 1999), further limiting their job potential. Women are also subject to lower wages (Fallon). Furthermore, female entrepreneurs experience a difficult challenge in their ability to access credit, due to their common lack of land ownership and limited resources within the cultural context of their society (Lloyd & Gage-Brandon, 1993; Safu & Manu, in press). These restrictions on resources among women are different across the numerous ethnic and tribal groups throughout the various regions in Ghana.

These perspectives provided a basis for program development and the need for educating Ghanaian female entrepreneurs and people who were responsible for creating the various programs to support their economic development. The Ghana Entrepreneurship Training Program thus attempted to account for the importance of empowerment within the context of the overlying cultural and structural barriers present in female entrepreneur-ship in Ghana.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT: U.S.–GHANA EXCHANGE MODEL

The Ghana Entrepreneurship Training Program was made possible through a grant from the U.S. Department of State Office of Citizen Exchange—Bureau of Education and Cultural Affairs. This one-year project was aimed at providing structural support and understanding of effective training for improving female entrepreneurship in Ghana. The project consisted of a collaboration that included a School of Social Work in the USA, the Department of Social Work in Ghana, and ZONTA international clubs in the United States and Ghana. The Ghana Entrepreneur-ship Training Program was designed to teach entrepreneurship skills to aid women in business idea creation, development and expansion, while discussing the business market, professional network structures, and resource development.

The first phase of this project included the establishment of an advisory board in the United States and Ghana as a point of reference for program planning and management. Both boards consisted of university faculty, staff, and students as well as community representatives. The initial task of both groups was to develop a protocol for interviewing and selecting participants for the exchange program that would include a 3-week stay in the United States. A selection committee interviewed more than twenty candidates who represented a cross-section of individuals working in the private, public, media, NGO/community, and higher education sectors throughout Ghana. From this process, ten individuals were chosen to participate in the exchange program in the United States. During the second phase, through on-site visits, the program in the United States gave participants an opportunity to closely examine the essential elements of entrepreneurship training specifically designed for women from diverse economic status. In addition to learning about the various guiding principles and operational structures of successful training organizations, they had several opportunities to join actual training sessions for prospective entrepreneurs. In addition, this time was used to begin to discuss aspects considered to be pertinent parts of the training in Ghana. This process included several focus group type meetings that clearly outlined the entrepreneurship needs for the country and aspects of the continued collaborative relationships. From the training perspective, the following were noted:

Technical assistance and information

Information on creating policy structures with emphasis on increasing support for women entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship training needs specific to women

Understanding microcredit loan programs with efficient monitoring protocols

The training must become institutionalized and required a sharing community—making information accessible

The dynamics of rural settings as it relates to entrepreneurship development must be acknowledged and become an aspect of the training

The most significant aspect noted for the training was the need to facilitate a structure to decrease barriers caused by blurred boundaries of women’s entrepreneurial financial expectations from their social and familial expectations. In most instances, the participants noted that Ghanaian women kept their business and family financial needs within the same financial domains. Therefore, there was no clear distinction between funds that were available for business capital from the funds needed to maintain the immediate and extended household needs. This was seen as being the number one cause for women’s failure to succeed in the various entrepreneurial endeavors. Furthermore, business diversity and professional network collaborative linkages were also seen as a factor leading to unsuccessful entrepreneurship. For example, women were not aware of each other’s areas of expertise or successful business ventures. Therefore, they were not able to refer or assist each other with various business knowledge or skills specific to their businesses. In an effort to ensure that these needs were met through the training in Ghana, the participants wanted to make sure that this was a mutual collaboration that combined entrepreneurial expertise from the United States with the cultural understanding of entrepreneurship from a Ghanaian perspective. These aspects became a very important function of the final phase of the project, which included the final design and implementation of the training in Ghana.

UNDERSTANDING AS AN ESSENTIAL COLLABORATIVE TOOL

The Ghana entrepreneurship training design was facilitated by two social workers who served as directors of microentrepreneurship programs and two other directors of similar programs in the United States. The team included a social work faculty member and two Master’s level social work students in the United States, along with faculty and community partners in Ghana. The faculty member on the U.S. team was the only member with an understanding of the Ghanaian culture. To ensure that the trainers and the student assistants understood the Ghanaian culture, a cultural competency and historical training was developed for them. This 2-day training was designed to create a heightened awareness and understanding of the cultural diversity found in Ghana among the numerous ethnic groups. The training for the trainers took an empowerment perspective to understanding culture, history, and diversity of people in the context of their community. By utilizing empowerment for the foundation of the training for the trainers, they began to understand the importance of understanding, emphasizing, and nurturing the strengths that are found in communities and using their new awareness to design change that allows the participants to assume power over their ultimate destiny. The training participants also learned about historical events that played a significant role in shaping a number of the governmental policies designed to provide assistants to women, children, and families. Again, this information was important as it increased their understanding of applying an empowerment practice perspective that seeks to (a) develop the capacity of people to understand their environment, make choices, take responsibility for those choices, and influence their life situation through advocacy for change; and (b) influence more equitable distribution of resources and power among different groups in society (Robbins, Chatterjee, & Canda, 2006). This empowerment with its focus on cultural and historical aspects was an important part of the trainers’ training because they needed to be factored into the training program design for successful implementation in Ghana.

Immediately following the training for the trainers, the team met to review the information obtained during the focus group sessions and used this to design a 4-day entrepreneurship training course. This training covered various aspects of business development such as business plan design, marketing, budgeting, and professional networking as key aspects of business success for women in the country. Each segment of the training included enrichment exercises for the participants to work on during the training day as well as at night. Again, the basis of the training was structured from an empowerment stance that focused on a strengths perspective for women. This was very important because within the Ghanaian context, women play a significant role as a part of the family's financial structure. However, societal demands and expectations often put them at a disadvantage as these expectations may distract their attention away from the demands of their business. These pressures can make changes for women very difficult especially if the primary emphasis is placed on mere verbal persuasion to facilitate the necessary changes needed to take control over their decision and the impact that they will have on their economic sustainability (Handy & Kassam, 2006). Therefore, this training went beyond the usual aspects needed to plan, design, and financially support a business. The program went a step further to provide some social entities that complemented the social behavior of women in Ghana as a key component to increasing their entrepreneurship success.

TOOLS OF ENGAGEMENT

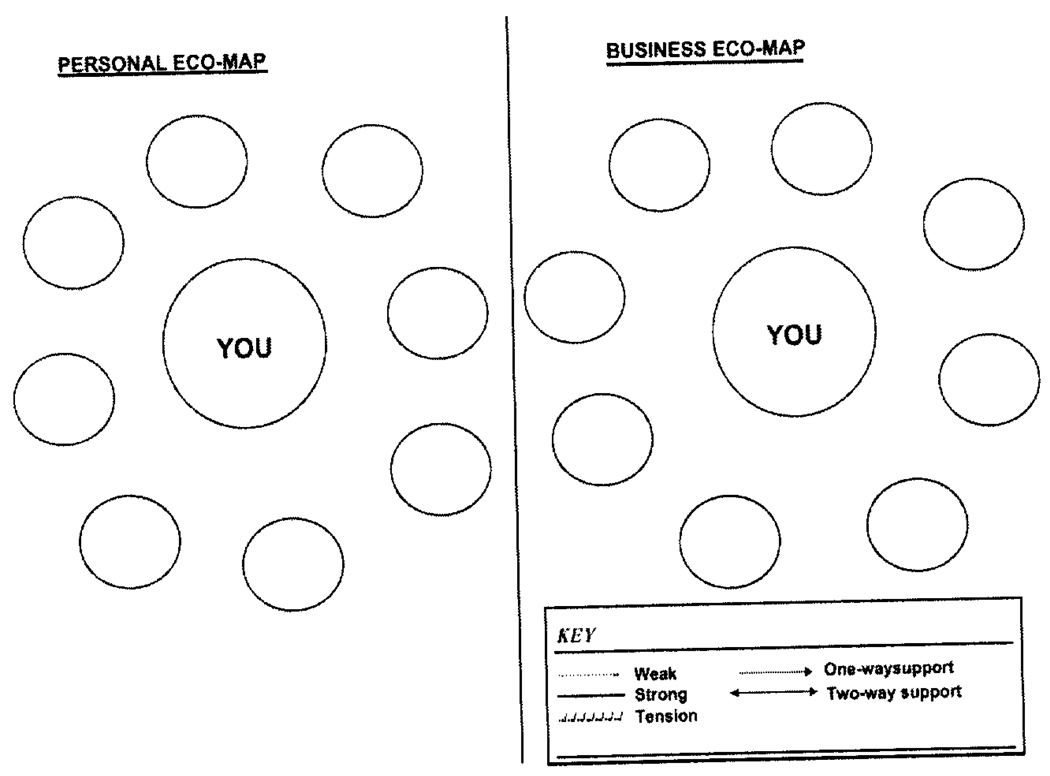

As with most microentrepreneurship programs, sessions must be designated to address business plan development, marketing financial dimensions to ensure success. While keeping within the context of previous training programs, we kept the traditional components and added two tools to increase communication and support for women in various settings. As a means for addressing the communication gaps among female entrepreneurs, we designed two tools of engagement. The first was the Readiness Assessment, which addressed each individual’s specific business plan and entrepreneurship needs corresponding to their particular geographic region. The second tool was the social relationships eco-map. This tool measured the strengths and differences between personal and business relationships identified by the participant. The trainers and the students worked with partners in Ghana to design the two tools and the students were trained on the appropriate use and data that would be found based on specific regions and categories of business ventures in Ghana.

The Readiness Assessment was designed to be used as a 15-minute individual meeting with each participant enrolled in the Entrepreneurship Training Program conducted by the two Master’s level social work students. The students were trained to use the tool in a manner similar to conducting an assessment with a new client in an agency setting. The tool was designed to discuss the business ideas of each enrollee as well as identify their areas of need. This assessment challenged participants to think and develop elements of starting a business. During the assessment, participants were asked to note their previous experiences and current roles in the community; they were encouraged to identify themselves as a trainer, entrepreneur, or ministry support personnel from various geographical regions. This was important because the training was designed to provide the trainers with tools and techniques that were transferable to similar entrepreneurship training services in their geographic areas. The women were asked the following questions: Which region(s) are you from? Which one applies to you: trainer, entrepreneur, or ministry/support? What type of business are you interested in? Describe your idea. What is the industry like? How would your business be unique? What are the financial start-up costs? What steps have you taken already? What other resources do you have (e.g., networking, supplies, finances, etc.)? What is your social support/networking like?

The women entrepreneurs were a select group of individuals seeking to start their own businesses or who had already started a business. Ministry support persons were present to gain knowledge and provide support toward establishing entrepreneurship in their own communities. Each program participant took part in the Readiness Assessment in order to understand their own needs, or the potential needs of the entrepreneurs that they would be training or supporting in the future. Furthermore, the Readiness Assessment facilitated discussions to allow participants to begin thinking about the necessary components needed to start their business. Each individual identified their desired business interest area as well as the industry status in their geographical region. They also defined start-up costs as well as identified steps that had already been taken to start a business. The participants continued by discussing resources that were already available to the entrepreneur. Finally, in order to successfully start a business, participants described their support and networking strategies and this information was used to design and facilitate network sessions. In addition to the Readiness Assessment Tool used during the Entrepreneurship Training Program, we also used the social relationships eco-map. This assessment tool was designed by the social work professor and the two social work students on site. It was created in direct response to the group dynamics during the training that indicated that there was a clear need for not only networking but for understanding the various network of relationships and the impact it might have on their business success. Furthermore, it was viewed as a tool for creating a sense of ownership of one’s destiny—ultimately, an empowerment tool.

The eco-map was used as part of a 60-minute session led by the social work students during the training that further discussed networking and relationship strategies needed to maintain a successful business. Participants began the session by completing the personal and business eco-maps. The eco-maps displayed participants’ names in the center circle, surrounded by several other circles as illustrated in Figure 1. Each circle represents a positive or negative relationship or network ties. The participants completed an eco-map for personal relationships and business networks separately in order to identify the differences between both categories. After writing names in each circle, participants defined the type of relationship or network as weak or strong. They also identified the level of support including weak, strong, tension, one-way support, or two-way support. This was conducted by using a line, identified in the worksheet legend corresponding to type and support level, to connect their names to each relationship or network. In addition, participants were able to use multiple lines in defining their relationships or networks. After this exercise, the group of individuals in the session engaged in discussions of their defined relationships and networks and the effect these may have on their businesses. The instructors used questions to elicit responses and facilitate discussion. These included identifying the difference within and between each business network and personal relationship, while describing positive and negative attributes. Strong, two-way support was defined as important for successful business networks and personal relationships.

FIGURE 1.

Eco-mapping social relationships.

Combined, these two social work-based tools provided an empowerment approach for addressing the problems inherent in decreasing women’s ability to succeed in their business endeavors. Both tools introduced the importance of reciprocal and reinforcing relationships that stimulates one’s ability to be empowered and supported. As noted by Handy & Kassam (2006), strategies that are purposefully introduced to enhance personal factors (self-efficacy) play a role in reinforcing behaviors (such as self-assertive behavior) that may have a significant impact and reinforce environmental factors that have lasting impact on various represented factors. This approach that utilizes a social work empowerment effort can be an essential aspect for creating economic sustainable entrepreneurship programs beyond the business skills taught in theses sessions in developing countries.

IMMEDIATE IMPACT

The Ghana Entrepreneurship Program consisted of 4-day training in Ghana. The training included 60 participants representing several regions throughout Ghana. During the first day of training, the participants completed the Readiness Assessment that provided data on their ability to design business plans, marketing skills, and financial start-up. In addition, the participants were given a program evaluation to assess the immediate impact of the program. The evaluation included four closed-ended questions using Likert-scaled responses and six open-ended questions. As illustrated in Table 1, the final evaluation was completed by 85% (N = 51) of the participants and it included rich qualitative data about the impact of the training.

Table 1.

Pre- and Post-business plan skill level (N = 51)

| Ranking | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-business plan skill level | ||

| Very poor | 2 | 3.9 |

| Poor | 3 | 5.9 |

| Average | 29 | 56.9 |

| Good | 10 | 19.6 |

| Excellent | 7 | 13.7 |

| Total | 51 | 100 |

| Post-business plan skill level | ||

| Very poor | 1 | 2 |

| Average | 11 | 21.6 |

| Good | 19 | 37.3 |

| Excellent | 20 | 39.2 |

| Total | 51 | 100 |

As previously noted, during the beginning phase of this project an important aspect that was missing from business development dimensions for women was a clear understanding of developing a useful business plan. Prior to the training, over 50% of the participants rated their ability to create a business plan as average. Another 33% self-rated as being good to excellent at this task. However, by the end of the training, over 75% of the participants rated their ability to successfully create a business plan between good and excellent. These statistics reflect a significant change in the participants’ self-rated ability before and after the training. This change can be connected to the trainers’ commitment to working with participants to create a sound business plan by the end of the training.

As research illustrates, a strong business plan is important to the success of a business because the document serves as a blueprint for building a business. With this in mind, the trainers spent a significant amount of time with students during the regularly scheduled training time and set hours during the evening to review and discuss ideas for the participants’ proposed business plans. As a part of the evaluation, participants were asked about the usefulness of the business plan that they created during the training. Over 95% of the participants noted that the plan would provide some significant impact on their ability to implement their business ideas. Although the business plan design and participants’ comfort level to design the plans was a significant aspect of the training, the networking segments that included the use of the eco-map was viewed as being a very useful and unique aspect of the training that made it more effective than the participants had previously attended. One participant stated the following:

This is extraordinary because it was practical and provided new skills around understanding your support network—more than theory.

Another participant noted that

this really brought out the practical way of illustrating key components for business success from a woman’s perspective with the exercises that gave a feel of doing the real thing.

From various indications it is clear that the Readiness Assessment and Eco-Map exercises were seen as an adaptable and user friendly training enhancement. Overwhelmingly, participants expressed gratitude for this aspect of the training. The following comment summarizes the group’s sentiment:

This training is an eye opener for anybody who has an idea and wants to develop it into a business … the exercises help you understand the different steps needed to take before you start a business. As a woman currently in business, the map exercise helped me understand my profits and the trail of my funds…thanks!!

This statement illustrates the level of empowerment that many of the participants felt from the overall training and specifically, the exercises that were embedded in social work practice. Each of the participants was allowed to keep their completed eco-map as a reminder of the various relationship network ties that supported or created barriers for their business success. They were also given extra copies before leaving the training site and were encouraged to use them and share with individuals who were not able to attend. Those who participated as community leaders who conduct trainings to support women entrepreneurship programs were given extra copies of the complete training manual for them to adapt as needed in their respective communities. The ultimate test of these exercises on enhancing training and success of women entrepreneurs in Ghana is illustrated in the follow-up stories in the next section.

WHERE ARE WE NOW—STORIES OF SUCCESS

Approximately 2.5 years following the initial training, the authors were able to locate three of the women who participated in the training that fit one of the following categories at the time of the training: (a) in the process of starting a business for the first time, (b) continuing with a current business, or (c) developing a new business after a failed business. These women lived in three different areas in the country and had different businesses as well. The women were asked to discuss their current business status and the use of any of the knowledge gained from participating in the training a few years ago.

Linda: Originally from the northern part of Ghana; had pottery and art business prior to the training. She attended the training to try to enhance and expand her current business. During a follow-up interview, she explained that the training gave her the tools and ideas needed to market her work beyond the few areas where she had been selling for a number of years. In fact, the network sessions at the training gave her an opportunity to meet with potential clients and business collaborators. When asked about the eco-map exercise, she thanked the training again for the exercise. She further explained that it has played a role in keeping up with her finances. It currently helps her with her banking and understanding for what and how funds should be used. Also, as she meets new people through her business exchange, she now thinks about their relationship in reference to the structure of her business and how that relationship might impact her business. She has remained successful in the pottery business and attributes the current success to the skills she gained at the training.

Ellen: Is currently residing in central Accra where she had continued to expand her businesses. Prior to attending the training, she had a beauty care shop stationed in front of her home and was beginning to use the capital to start a car rental business. At the time of her follow-up interview, she began to ask questions about the team from the United States while remembering the training experience. When asked about the long-term impact of the training, she happily noted that it had been extremely helpful. Her favorite aspects were the business plan exercises and the eco-map. She noted that those two components helped to facilitate her new business ventures. Currently, she has expanded to include a very small car rental business in addition to the beauty care shop. Although she only has 2 cars to rent, she has established relationships with other car rental business and she now acts as an agent referring clients to the other businesses for cars and bus rental. This was the business plan that she worked on during the training and the eco-map exercise has helped her facilitate and maintain relationships that has led to her ability to coordinate with folks to make referrals and rent her two cars. As with the other participant, she also noted that she views relationships differently in the context of the linkage they have to the success of her business. She is pleased that she had the opportunity to participate in the exchange program and the training.

Mary: Mary can be viewed as one of the prime candidates for the original training. She was single with several children and no employment at the time of the training. She had had a few businesses in the past that failed for a number of reasons. During her follow-up, she continued to be thankful for the opportunity and pleased with the outcome. Although she is still struggling with her business, she attributes her current state of being self-employed to the training. She came to the training with an idea of starting a business selling clothing in a prime location near her home. She noted that the one-on-one business plan assistance was extremely helpful. However, the exercise with the circles (eco-map) helped her to formulate a strategy for people to contact for assistance with her new business venture. This led to her viewing individuals in her current circle of friends as potential sources of support in various ways. She now refers to those friends who have been, and are potential sources of financial or social support, as her strong circle individuals. Those who are deemed as not being helpful in the process are now referred to as broken circle of friends that may not mix with her business plans. Although she is not where she would like to be financially, she stated that she is grateful for the tools and the opportunity to participate in the training, it has allowed her to think more economically about her business and the impact that financial decisions have on the future success of her business.

These three stories highlight the impact of the training and the level of empowerment that these women obtain through the various structured traditional and nontraditional exercises. It was great to hear that the Eco-Map was being used in their everyday ventures and assisting them with relationship and financial stability as they continued to move forward in their business endeavors. It is clear that social network pieces in the training provided a practical aspect to business development.

CONCLUSION

While significant challenges exist, entrepreneurship training specifically for women may allow easier transition into self-employment and microentrepreneurship. Several studies suggest that higher levels of education serve to create an easier transition into entrepreneurial positions (Dolinsky, Caputo, Pasumarty, & Quazi, 1993). Similarly, while individuals with higher levels of education are less present in entrepreneurial activities, it is indicated that education and training are very important in allowing women to enter into self-employment (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2002; Verheul, van Stel, & Thurik, 2006). More specifically, Vijverberg (1995) found that higher levels of education were correlated with increased income for Ghanaian entrepreneurs. In addition, higher levels of education for women do suggest increased female involvement in entrepreneurship (Verheul et al., 2006). Furthermore, these higher levels of education may also correlate with the increased likelihood that individuals will want to use the skills they have developed (Coleman & Pencavel, 1993; Verheul et al., 2006). This may imply that entrepreneurship training could improve skill development as well as the interest and transition into entrepreneurship for women in Ghana.

Several essential factors were necessary to account for when developing this program. First, small business training must be related to small business and subsequently not related to the management of large organizations (Nieman, 2001). Educators and trainers must be sufficiently aware of African cultures and language, especially in rural areas where many traditional values and beliefs are prevalent (Nieman, 2001; Smets, 1996). They must also have business experience and be supportive of trainees (Nieman, 2001). In addition, small business training must be simple and easy to understand, while including hands-on activities and facilitating discussion on business matters relevant to the group (Nieman, 2001). This aspect has shown to be significant in the case of the Ghanaian Entrepreneurship Training Program. The Readiness Assessment and Eco-Map were very hands-on and practical, yet provided a new level of awareness for the women. Furthermore, the eco-map allowed the women to begin to think about relationship ties that provided them with some level of support, moving away from the role of providing all levels of support—psychologically and financially. Finally, while it may be important to include information on business supply, the needs of the entrepre- neurs must first be taken into consideration (Nieman, 2001). These needs can be understood only through an understanding of the culture(s) that are specific to the country and region that the program is being designed for.

While accounting for these program guidelines in providing the basic skills necessary in entrepreneurial training, it is critical to examine the distinct cultural context evident in developing countries, especially Ghana. Additionally, Chamlee-Wright (1997) suggests that cultural context must also be taken into consideration for economic development to occur within a country, especially in West Africa. The importance of looking at entrepreneurship development from a gender and cultural perspective is extremely important for the economic stability of the women, their families, and their country. Like most places in Africa, Ghanaian women are usually the financial pillar of the family and the social network facilitator as well. Understanding their roles and creating programs that take this into account illustrates an understanding of the cultural context and constraints against which they are working. Thus, programs can be designed to meet the needs of women in the context of their society, culture, and community with an emphasis on empowerment. It is clear that social work practice skills should not be overlooked as an aspect of these programs, using the culture and community as the framework for creating tools of engagement for an international community.

Contributor Information

DeBrenna L. Agbényiga, Assistant Professor, Michigan State University, School of Social Work..

Brian K. Ahmedani, Email: ahmedan2@msu.edu, Doctoral Student, Michigan State University, School of Social Work..

REFERENCES

- Bloom DE, Sachs JD, Collier P, Udry C. Geography, demography, and economic growth in Africa. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1998;29(2):207–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DD, Hisrich RD. The female entrepreneur: A career development perspective. The Academy of Management Review. 1986;11(2):393–407. [Google Scholar]

- Chamlee-Wright E. The cultural foundations of economic development: Urban female entrepreneurship in Ghana. New York: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chitsike C. Culture as a barrier to rural women’s entrepreneurship. In: Sweetman C, editor. Gender in the 21st Century. Simi Valley, CA: Oxfam; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MT, Pencavel J. Trends in market behavior of women since 1940. Industrial Labor Relations Review. 1993;46(4):653–676. [Google Scholar]

- Dolinsky AL, Caputo RK, Pasumarty K, Quazi H. The effects of education on business ownership: A longitudinal study of women. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 1993;18(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon KM. Education and perceptions of social status and power among women in Larteh, Ghana. Africa Today. 1999;46(2):67–91. doi: 10.1353/at.1999.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese M, editor. Success and failure of microbusiness owners in Africa: A psychological approach. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Glewwe P, Jacoby H. Student achievement and schooling choice in low-income countries: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Human Resources. 1994;29(3):843–864. [Google Scholar]

- Handy F, Kassam M. Practice what you preach? The role of rural NGOs in women’s empowerment. Journal of Community Practice. 2006;14(3):69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CB, Gage-Brandon AJ. Women’s roles in maintaining households: Family welfare and sexual inequality in Ghana. Populations Studies. 1993;47(1):115–131. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Attafuah J. Consumer confidence in Ghana and its implications for survey-based economic indicators in Africa. Social Indicators Research. 2004;65:207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Moore DP. An examination of present research on the female entrepreneur—suggested research strategies for the 1990s. Journal of Business Ethics. 1990;9(45):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Naffziger DW, Hornsby JS, Kuratko DF. A proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 1994;18:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nieman G. Training entrepreneurs and small business enterprises in South Africa: A situational analysis. Education & Training. 2001;43(89):445–450. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill RC, Viljoen L. Support for female entrepreneurs in South Africa: Improvement or decline? Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences. 2001;29:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- OECD employment outlook: July 2002. Paris: Author; 2002. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [Google Scholar]

- Robbins SP, Chatterjee P, Canda ER. Contemporary human behavior theory: A critical perspective For social work. 2nd ed. Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saffu K, Manu T. Strategic capabilities of Ghanaian female business owners and the performance of their ventures. National Women’s Council and the International Council of Small Business Conference in South Africa. 2004 Available at http://www.nwbc.gov/ICSB,Best-Paper.2004.pdf.

- Scherer RF, Brodzinski JD, Wiebe FA. Journal of Small Business Management. 2. Vol. 28. 1990. Entrepreneur career selection and gender: A socialization approach; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir A, Di Gregorio S. An examination of the relationship between women’s personal goals and structural factors influencing their decision to start a business: The case of Pakistan. Journal of Business Venturing. 1996;11(6):507–529. [Google Scholar]

- Smets P. Community-based finance systems and their potential for urban self-help in a new South Africa. Development Southern Africa. 1996;12(1):173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Somavia J. Director general address. International Labor Organization (ILO) 11th regional meeting in Addis Ababa.2007. [Google Scholar]

- Verheul I, van Stel A, Thurik R. Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. 2006;18(2):151–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vijverberg WPM. Returns to schooling in non-farm self-employment: An econometric case study of Ghana. World Development. 1995;23(7):1215–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Wennekers S, Thurik R. Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Business Economics. 1999;13(1):27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Woldie A, Adersua A. Female entrepreneurs in a transitional economy: Businesswomen in Nigeria. International Journal of Social Economics. 2004;3(12):78–93. [Google Scholar]