Abstract

Oestradiol (E2) exerts critical homeostatic feedback effects upon gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons to maintain fertility. In the female, E2 has both negative and positive feedback actions to suppress and stimulate GnRH neuron activity at different times of the ovarian cycle. This review summarizes reported rapid E2 effects on native embryonic and adult GnRH neurons and attempts to put them into a physiological perspective. Oestrogen has been shown to rapidly modulate multiple processes in embryonic and adult GnRH neurons including intracellular calcium levels, electrical activity and specific second messenger pathways, as well as GnRH secretion itself. Evaluation of in vivo data suggests that there is no essential role for rapid E2 actions in the positive feedback mechanism but that they may comprise part of the negative feedback pathway. Adult GnRH neurons are only likely to be exposed to E2 from the gonads via the circulation with appropriate physiological E2 concentrations in the rodent being 10–50 pm for negative feedback ranging up to 400 pm for positive feedback. Although most studies to date have examined the effects of supraphysiological E2 levels on GnRH neurons, there is accumulating evidence that rapid E2 actions may have a physiological role in suppressing GnRH neuron activity.

The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons of the hypothalamus control the release of the gonadotropic hormones, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), from the pituitary gland. As such they represent the final neural signalling pathway controlling reproduction in all mammals. The principle homeostatic control mechanism keeping the GnRH neurons in tune with the state of the gonads is termed gonadal steroid feedback (Herbison, 2006). In males, circulating testosterone levels maintain a suppressive or negative feedback influence upon the activity of the GnRH neurons. In females, the feedback mechanisms are more complex in that, while oestrogen and progesterone evoke negative feedback, they also have a positive feedback role responsible for generating the pre-ovulatory GnRH and LH surge (Herbison, 2006). Hence, the fertility of an individual is critically dependent upon complex gonadal steroid feedback mechanisms that ultimately control the activity of the GnRH neurons.

It is now clear that oestrogens, in particular 17-β-oestradiol (E2), exert rapid (also termed ‘non-genomic’ or ‘membrane initiated’) effects on many neurons located throughout the brain (McEwen & Alves, 1999; Maggi et al. 2004; Ronnekleiv & Kelly, 2005; Mermelstein & Micevych, 2008). The realization that E2 exerts such rapid effects on multiple neuronal functions has, however, been a gradual process considering that the first accounts of rapid oestrogen actions on neurons were reported over 35 years ago (e.g. Yagi, 1973; Kelly et al. 1976). While considerable progress has been made in defining the cellular mechanisms of rapid oestrogen action in several neuronal phenotypes (Ronnekleiv & Kelly, 2005; Mermelstein & Micevych, 2008), their physiological relevance has remained much more difficult to ascertain (Cornil et al. 2006).

As GnRH neurons represent a neural population for which there are well-established physiological roles for E2, they might provide one model system for deciphering the physiological significance of rapid E2 actions. Whereas GnRH neurons express only oestrogen receptor beta (ERβ) (Herbison & Pape, 2001), other glia and neuronal afferent inputs within the GnRH neuronal network express both ERα and ERβ (Herbison, 2006; Wintermantel et al. 2006). This review summarizes briefly the known rapid effects of E2 on native GnRH neurons and then attempts to place them in a physiological context.

Rapid E2 effects on adult GnRH neuron cell bodies

The first study reporting rapid effects of E2 on GnRH neurons came from the Kelly laboratory. Using an arduous, post hoc identification procedure in guinea-pig brain slices, they reported that nanomolar E2 rapidly hyperpolarized GnRH neurons located in the mediobasal hypothalamus (Kelly et al. 1984; Lagrange et al. 1995) (Fig. 1A). This seminal work set the scene for direct rapid oestrogen effects on GnRH neuron excitability but required a wait of nearly 10 years before the next accounts of rapid E2 action on GnRH neurons were to be reported. Using GnRH transgenic mice, that greatly facilitate direct recording from GnRH neurons in acute brain slices, two laboratories have reported direct and indirect rapid E2 effects on adult female GnRH neurons.

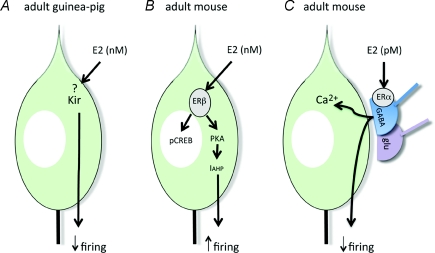

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of reported pathways of rapid estrogen action on adult GnRH neurons.

A detailed investigation from the Moenter laboratory has documented two different effects of E2 on GnRH neuron cell firing (Chu et al. 2009). At ≥ 100 pm concentrations, E2 was found to rapidly and directly activate firing in most GnRH neurons through a mechanism involving ERβ, protein kinase A and the suppression of calcium-activated potassium channels underlying the after-hyperpolarization potential (Fig. 1B). However, E2 at lower concentrations (10 pm) had no direct effect on GnRH neurons, but instead inhibited firing using a complex, indirect pathway likely to involve both ERα and ERβ modulation of GABA and glutamate inputs to GnRH neurons (Fig. 1C).

Our own initial study examined the ability of E2 to phosphorylate cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in mouse GnRH neurons in the acute brain slice and in vivo (Abrahám et al. 2003). We found that 1 μg per mouse (in vivo) or 100 nm (in vitro) E2 rapidly (15 min) increased CREB phosphorylation in a subpopulation of GnRH neurons, and that this effect was direct and mediated by intracellular ERβ (Fig. 1B).

We recently examined the effects of E2 on intracellular calcium concentrations in adult GnRH neurons in brain slices prepared from GnRH-Pericam transgenic mice (Romano et al. 2008). These experiments showed that E2 over a wide concentration range (100 pm to 100 nm) initiated calcium transients within 15 min in ∼40% of GnRH neurons. This effect was not direct but shown to be mediated by ERα-expressing GABAergic nerve terminals (Fig. 1C).

Rapid E2 effects on adult GnRH nerve terminals

Drouva and colleagues (Drouva et al. 1984) reported that 100 pm to 100 nm E2 was able to increase potassium-evoked GnRH release from mediobasal hypothalamic explants from ovariectomized rats. This effect occurred rapidly suggesting that E2 may also target the GnRH neuron nerve terminal to modulate secretion. A subsequent study by Prevot and co-workers (Prevot et al. 1999) provided mechanistic detail to this effect by showing that E2 targeted endothelial cells to enhance nitric oxide release onto adjacent GnRH nerve terminals.

Rapid E2 effects on cultured embryonic GnRH neurons

Apart from an important role in the process of sexual differentiation, the functions and concentrations of E2 in the developing embryonic brain are unknown. Nevertheless, cultured embryonic nasal placode cultures have provided an important means to investigate the developing GnRH neuron at a cellular level. Two laboratories have undertaken comprehensive investigations into rapid E2 actions on GnRH neurons in this preparation.

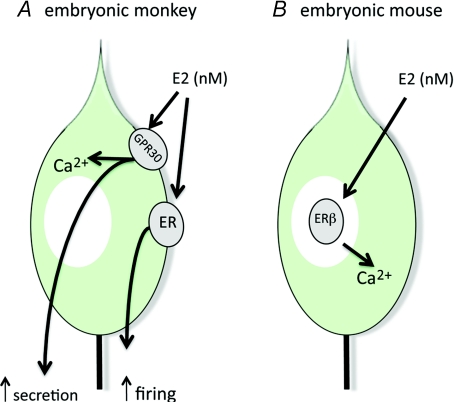

Terasawa and co-workers have shown that 1 nm E2 induces a rapid (1–2 min) increase in (i) GnRH neuron firing rate and burst duration (Abe & Terasawa, 2005), (ii) frequency of calcium oscillations (Abe et al. 2008) and (iii) GnRH secretion from the explants (Noel et al. 2009). While the firing rate change was blocked by the classical nuclear ER antagonist ICI182780, the calcium oscillations and GnRH secretion changes were shown to be dependent upon a membrane-located oestrogen receptor (Abe et al. 2008) and this was recently revealed to be GPR30 (Noel et al. 2009; Terasawa et al. 2009) (Fig. 2A). The reasons for the interesting discordance between the subcellular mechanisms underlying the E2 modulation of firing and secretion are unclear but might represent soma versus terminal effects of E2 in this preparation.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing reported rapid estrogen effects on embryonic cultured GnRH neurons.

Using a mouse nasal placode model, Wray and colleagues have reported similar effects in that 1 nm E2 was able to increase the frequency of calcium oscillations in ‘early-cultured’ GnRH neurons, although this effect was slower taking approximately 30 min (Temple et al. 2004). The mechanism underlying this action of E2 was quite different to that seen in the monkey, however, as it required E2 entry into the GnRH neuron, ERβ and gene transcription (Temple et al. 2004) (Fig. 2B). As an important technical aside, these authors also reported that three different E2-bovine serum albumin molecules, commonly used to define membrane-delimited E2 actions, had quite different effects on GnRH neuron calcium levels (Temple & Wray, 2005).

Commonalities and discrepancies in rapid E2 actions on GnRH neurons

Given the range of experimental preparations, species, and methods of investigation, it is not too surprising to find little commonality amongst the results of the studies undertaken to date. In particular, adult GnRH neurons in situ are in a very different developmental state and environment compared with cultured embryonic GnRH neurons. It seems that only molecules of great physiological importance within the GnRH neuronal network, such as kisspeptin (Popa et al. 2008), can transcend these substantial experimental differences. Nevertheless, some shared features of rapid E2 are apparent:

(1) With the exception of the guinea-pig study, nanomolar levels of E2 activate firing or calcium transients in adult or embryonic GnRH neurons from mice and monkeys. However, the mechanisms underlying these stimulatory effects differ in a species-specific manner; GPR30 is critical for the monkey (Terasawa et al. 2009) but has no role in mice where ERβ is required either for intracellular kinase activation (Abrahám et al. 2003; Chu et al. 2009) or rapid transcriptional events (Temple et al. 2004). At present, it is not clear what advantage GPR30 would provide over ERβ in generating this activation. The use of ERβ would enable E2 to generate co-ordinated genomic, intracellular kinase and electrical regulation (Fig. 1B). However, it remains that a physiological role for ERβ in GnRH neurons has yet to be established; mice with a GnRH neuron-specific deletion of ERβ exhibit normal negative and positive feedback and fertility (R. Porteous & A. E. Herbison, unpublished observations).

(2) Low picomolar levels of E2 have no direct effects on GnRH neurons but, instead, exert rapid indirect actions through presynaptic modulation of GABA, and probably glutamate, afferent inputs to these cells (Romano et al. 2008; Chu et al. 2009). The apparent absence of these effects in cultured embryonic GnRH neurons is not surprising considering that they will not have had the opportunity to develop an adult-like pattern of GABA and glutamate afferent inputs (Clarkson & Herbison, 2006).

What concentration of E2 is physiological?

A crucial issue in the field of rapid oestrogen actions is that of concentration with the majority of studies using E2 concentrations well above those found in the circulation. In female rats and mice, circulating E2 levels range from 15 to 40 pm during times of negative feedback, rising to 300–400 pm during the oestrogen positive feedback phase, with levels in the adult monkey being higher ranging from 100 to 1000 pm (for review see Cornil et al. 2006). Assuming that the lipophilic nature of E2 allows free access and distribution within the brain, this means that rodent GnRH neurons will be bathed in low picomolar concentrations during negative feedback and high picomolar levels during the positive feedback phase.

The only other source of E2 in the brain would be from local synthesis and it has been argued that ‘hot spots’ of aromatase expression may drive local E2 concentrations to higher levels than that obtained from the circulation alone (Cornil et al. 2006). As aromatase activity can be regulated rapidly by neurotransmitter inputs, E2 from this source may also fluctuate in a rapid manner (Balthazart & Ball, 2006). Whether GnRH neurons are impacted by E2 from local aromatization is not known. However, this seems unlikely as the nearest aromatase-expressing neurons are found some distance away from the GnRH neuron cell bodies in the medial preoptic nucleus (Wagner & Morrell, 1996). It also seems unlikely on the basis that correct homeostatic control requires GnRH neurons to sense circulating E2, and the interposition of an independently controlled local E2 source would be counterproductive to this role.

In this context, it would seem reasonable to state that E2 levels in the 10–50 pm range are physiologically relevant negative feedback concentrations whereas E2 levels in the 100–400 pm range represent physiologically relevant positive feedback concentrations in the rodent. As such, experimental E2 concentrations above 500 pm, and certainly those in the nanomolar range, are supraphysiological for rodent GnRH neurons and may be of limited use in determining the physiological relevance of rapid E2 actions in the GnRH neuronal network.

Is there a role for rapid E2 actions in positive feedback homeostasis?

At present, data indicate that there is no essential role for rapid oestrogen actions in the oestrogen positive feedback mechanism controlling ovulation. Early studies recognized that oestrogen positive feedback required many hours of exposure to E2 (Karsch et al. 1997), compatible with classic genomic actions, and further experiments have demonstrated that E2 need not be present at the actual time of the GnRH surge (Legan et al. 1975; Evans et al. 1997). More recent studies using transgenic mouse models have found that oestrogen positive feedback is totally dependent upon oestrogen response element (ERE) binding of oestrogen receptor alpha (ERα) (Glidewell-Kenney et al. 2007). Together, these and other studies (Wintermantel et al. 2006) signify that the oestrogen positive feedback mechanism does not require rapid oestrogen signalling. This is not to say that rapid E2 actions in the physiological range for positive feedback (GnRH neuron cell body and terminal activation by 100 pm E2 in mouse) do not occur, but rather that they are not essential under normal physiological circumstances.

Is there a role for rapid E2 actions in negative feedback homeostasis?

In contrast to positive feedback, the faster temporal dynamics of oestrogen negative feedback suggest that rapid oestrogen actions may be involved. Oestrogen is found to suppress GnRH secretion in < 2 h in ovariectomized rats, sheep and monkeys (Sarkar & Fink, 1980; Caraty et al. 1989; Mizuno & Terasawa, 2005). While classical genomic mechanisms of action are certainly possible in this time frame (e.g. immediate early genes such as c-Fos), it seems more likely that E2 uses other mechanisms to at least initiate the suppression of GnRH, and consequently LH, secretion. Perhaps the best evidence to date for non-classical mechanisms in oestrogen negative feedback is the observation that basal LH levels in mutant mice bearing an ERα with a mutated oestrogen response element binding domain are intermediate between those of intact and ovariectomized mice (Zhao et al. 2009). This suggests that oestrogen negative feedback suppression of LH occurs through both classical and non-ERE-dependent ERα signalling mechanisms, a part of which may result from rapid membrane-initiated E2 signalling. It has been argued previously that E2 negative feedback results from a multi-modal E2 mechanism involving direct and indirect glial and trans-synaptic mechanisms operating in multiple temporal dimensions (Herbison, 1998). Importantly, rapid E2 is unable to suppress LH secretion in ER single or double knockout mice (Abrahám et al. 2003) (I. M. Abrahám & A. E. Herbison, unpublished observations) demonstrating that classical ERs are essential for the initial negative feedback response and any rapid inhibitory E2 actions in this species.

In terms of documented rapid E2 actions, only one study has shown physiologically relevant E2 actions for negative feedback with Chu and co-workers demonstrating that 10 pm E2 rapidly inhibited GnRH neuron firing by modulating GABAergic afferents to these cells (Chu et al. 2009). While this effect seems entirely compatible with E2 suppressing GnRH neuron firing to achieve E2 negative feedback, it is not in agreement with other work from this laboratory showing that suppressed GnRH neuron firing during chronic negative feedback is entirely dependent upon classical ERE-mediated ERα signalling (Christian et al. 2008). This may, however, be a case where rapid E2 effects predominate early in the negative feedback process while more classical E2 mechanisms dominate later on (Herbison, 1998).

Is there a role for rapid E2 actions in sexual differentiation of GnRH neurons during development?

Embryonic GnRH neurons from both the monkey and mouse demonstrate rapid, robust responses to high supraphysiological (Temple et al. 2004) or positive feedback levels of E2 (Terasawa et al. 2009). The physiological significance of these actions in embryonic neurons is unclear. However, it is well established that E2 exerts important sexually differentiating effects on developing GnRH neurons in the perinatal period (Wood & Foster, 1998) and this may involve a rapid E2 component. This avenue of investigation does not appear to have been explored.

Summary and conclusions

It is evident that E2 can exert multiple rapid effects upon embryonic and adult GnRH neurons. Deciphering which of these effects are physiologically relevant is challenging, particularly given that most investigators, including ourselves, have used supraphysiological E2 concentrations. An argument is made here that local brain E2 production is unlikely to be relevant to GnRH neurons and that, as such, only low picomolar concentrations of E2 should be used in rodent studies; monkey GnRH neurons may be exposed to up to 1 nm E2 at times of positive feedback. In many cases, investigators use high supraphysiological E2 concentrations as this is what is required to achieve an effect (Cornil et al. 2006); while this strategy may be effective from a publication point of view, it will probably not help advance our understanding of how E2 regulates GnRH neurons.

Do rapid E2 actions have a role in GnRH neuron E2 homeostatic feedback? Present data indicate no critical or essential role for rapid E2 actions in the E2 positive feedback mechanism. While rapid effects with high physiological E2 can be measured, in vivo data suggest that they make little contribution to positive feedback, at least under normal circumstances. In contrast, there is possibly a role for rapid E2 actions within the negative feedback mechanism. Presently, the most convincing evidence for this is the ability of 10 pm E2 to indirectly suppress GnRH neuron firing in the mouse (Chu et al. 2009), although the precise mechanism remains to be established. Further studies examining the effects of low 10–50 pm E2 levels on GnRH neurons are warranted.

Finally, it is important to highlight that while the term ‘rapid E2 effect’ is a correct experimental description, it is a misnomer in a physiological sense. Circulating E2 levels do not change rapidly and, apart from those neurons located near aromatase-expressing cells (Balthazart & Ball, 2006), neurons will be exposed to very steady E2 levels changing, at the most, very gradually over several hours. Thus, the ‘rapid’ E2 mechanisms deciphered here are nevertheless persistent, and this fact appears to receive little attention. For example, it is rare to find studies comparing the effects of rapid E2 in ovariectomized animals to the status of intact animals (Abrahám et al. 2003). Once it is appreciated that the rapid E2 mechanism is persistent, the key issue then becomes one of whether or not the rapid mechanism is dose dependent within the relevant physiological E2 levels. This will require careful analysis of the effects of small steps of picomolar E2 concentrations and an assessment of the pharmacodynamics of the receptors involved. If rapid E2 actions on GnRH neurons are not dose dependent, then it could be argued that the rapid E2 mechanism is static in a physiological sense and might best be considered part of the background machinery of the cell. One logical extension of this concept would be to suggest that all work with ovariectomized tissue (i.e. brain slices and cultures) should include low picomolar E2 in the bathing solution or culture medium to ensure that the mechanism under examination is observed in a physiological context. To do otherwise might risk the danger of understanding the ‘physiology’ of the ovariectomized animal.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Dr Martin Kelly for useful comments on an earlier draft and all past and present members of the Herbison laboratory who have contributed to rapid oestrogen studies. This work was supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council.

References

- Abe H, Keen KL, Terasawa E. Rapid action of estrogens on intracellular calcium oscillations in primate luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone–1 neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:1155–1162. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe H, Terasawa E. Firing pattern and rapid modulation of activity by estrogen in primate luteinizing hormone releasing hormone–1 neurons. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4312–4320. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahám IM, Han SK, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Estrogen receptor β mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5771–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Ball GF. Is brain estradiol a hormone or a neurotransmitter? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraty A, Locatelli A, Martin GB. Biphasic response in the secretion of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone in ovariectomized ewes injected with oestradiol. J Endocrinol. 1989;123:375–382. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1230375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA, Glidewell-Kenney C, Jameson JL, Moenter SM. Classical estrogen receptor α signalling mediates negative and positive feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron firing. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5328–5334. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Andrade J, Shupnik MA, Moenter SM. Differential regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron activity and membrane properties by acutely applied estradiol: dependence on dose and estrogen receptor subtype. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5616–5627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0352-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson J, Herbison AE. Development of GABA and glutamate signalling at the GnRH neuron in relation to puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254–255:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil CA, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Functional significance of the rapid regulation of brain estrogen action: where do the estrogens come from? Brain Res. 2006;1126:2–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouva SV, Laplante E, Gautron J-P, Kordon C. Effects of 17β-estradiol on LH-RH release from rat mediobasal hypothalamic slices. Neuroendocrinology. 1984;38:152–157. doi: 10.1159/000123883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NP, Dahl GE, Padmanabhan V, Thrun LA, Karsch FJ. Estradiol requirements for induction and maintenance of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge: implications for neuroendocrine processing of the estradiol signal. Endocrinology. 1997;138:5408–5414. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glidewell-Kenney C, Hurley LA, Pfaff L, Weiss J, Levine JE, Jameson JL. Nonclassical estrogen receptor α signalling mediates negative feedback in the female mouse reproductive axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8173–8177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE. Multimodal influence of estrogen upon gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:302–330. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE. Physiology of the GnRH neuronal network. In: Neill JD, editor. Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction. 3rd edn. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1415–1482. [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Pape JR. New evidence for estrogen receptors in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:292–308. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsch FJ, Bowen JM, Caraty A, Evans NP, Moenter SM. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone requirements for ovulation. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:303–309. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Moss RL, Dudley CA. Differential sensitivity of preoptic-septal neurons to microelectrophoresed estrogen during the estrous cycle. Brain Res. 1976;114:152–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)91017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Rønnekleiv OK, Eskay RL. Identification of estrogen-responsive LHRH neurons in the guinea pig hypothalamus. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange AH, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Estradiol-17β and m-opioid peptides rapidly hyperpolarize GnRH neurons: a cellular mechanism of negative feedback. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2341–2344. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legan SJ, Coon GA, Karsch FJ. Role of estrogen as initiator of daily LH surges in the ovariectomized rat. Endocrinology. 1975;96:50–56. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Alves SE. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:279–307. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi A, Ciana P, Belcredito S, Vegeto E. Estrogens in the nervous system: mechanisms and nonreproductive functions. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:291–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.154945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein PG, Micevych PE. Nervous system physiology regulated by membrane estrogen receptors. Rev Neurosci. 2008;19:413–424. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2008.19.6.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M, Terasawa E. Search for neural substrates mediating inhibitory effects of oestrogen on pulsatile luteinising hormone-releasing hormone release in vivo in ovariectomized female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:238–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel SD, Keen KL, Baumann DI, Filardo EJ, Terasawa E. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) in rapid action of estrogen in primate LHRH neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:349–359. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa SM, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. The role of kisspeptins and GPR54 in the neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot V, Croix D, Rialas CM, Poulain P, Fricchione GL, Stefano GB, Beauvillain JC. Estradiol coupling to endothelial nitric oxide stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release from rat median eminence via a membrane receptor. Endocrinology. 1999;140:652–659. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N, Lee K, Abraham IM, Jasoni CL, Herbison AE. Nonclassical estrogen modulation of presynaptic GABA terminals modulates calcium dynamics in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5335–5344. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Diversity of ovarian steroid signalling in the hypothalamus. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:65–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Fink G. Luteinizing hormone releasing factor in pituitary stalk plasma from long-term ovariectomized rats: effects of steroids. J Endocrinol. 1980;86:511–524. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0860511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Laing E, Sunder A, Wray S. Direct action of estradiol on gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neuronal activity via a transcription-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6326–6333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1006-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JL, Wray S. Bovine serum albumin-estrogen compounds differentially alter gonadotropin-releasing hormone-1 neuronal activity. Endocrinology. 2005;146:558–563. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasawa E, Noel SD, Keen KL. Rapid action of oestrogen in luteinising hormone-releasing hormone neurones: the role of GPR30. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner CK, Morrell JI. Distribution and steroid hormone regulation of aromatase mRNA expression in the forebrain of adult male and female rats: a cellular-level analysis using in situ hybridization. J Comp Neurol. 1996;370:71–84. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960617)370:1<71::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermantel TM, Campbell RE, Porteous R, Bock D, Grone HJ, Todman MG, Korach KS, Greiner E, Perez CA, Schutz G, Herbison AE. Definition of estrogen receptor pathway critical for estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and fertility. Neuron. 2006;52:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RI, Foster DL. Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Rev Reprod. 1998;3:130–140. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi K. Changes in firing rates of single preoptic and hypothalamic units following an intravenous administration of estrogen in the castrated female rat. Brain Res. 1973;53:343–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Park C, McDevitt MA, Glidewell-Kenney C, Chambon P, Weiss J, Jameson JL, Levine JE. p21-Activated kinase mediates rapid estradiol-negative feedback actions in the reproductive axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7221–7226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812597106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]