Abstract

Vascular endothelial cells (ECs) are continuously exposed to mechanical stimuli (e.g., shear stress). Our previous study has shown that the shear-induced nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation is mediated by integrins [Bhullar, I. S., Y. S. Li, H. Miao, E. Zandi, M. Kim, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30544–30549, 1998]. The shear-activated integrins can also transactivate Flk-1 (a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) [Wang, Y., H. Miao, S. Li, K. D. Chen, Y. S. Li, et al. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283:C1540–C1547, 2002], which subsequently recruits Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (Cbl) to regulate inhibitor of κB protein kinase (IKK) [Wang, Y., J. Chang, Y. C. Li, Y. S. Li, J. Y. Shyy, and S. Chien. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286:H685–H692, 2004], an upstream molecule of NF-κB. Therefore, shear stress may likely utilize the Flk-1/Cbl pathway in regulating NF-κB. In this paper, we confirmed that the inhibition of Flk-1 by its specific inhibitor SU1498 blocked the shear-induced NF-κB translocation. The inhibition of Cbl (an adaptor protein which binds to Flk-1 upon shear) by using a negative mutant (Cblnm) also blocked the promoter activity of NF-κB, and the inhibition of the Cbl-downstream molecule phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) abolished the NF-κB translocation. Further experiments revealed that the disruption of actin cytoskeleton inhibited the Flk-1 and Cbl interaction and NF-κB translocation. The inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases, which are involved in the integrin-mediated focal adhesion complex, also blocked the shear-induced NF-κB translocation. Together with our previous findings that integrins mediate the shear-induced activation of Flk-1 and NF-κB [Bhullar, I. S., Y. S. Li, H. Miao, E. Zandi, M. Kim, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30544–30549, 1998; Wang, Y., H. Miao, S. Li, K. D. Chen, Y. S. Li, et al. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 283:C1540–C1547, 2002], the present results suggest that Flk-1, Cbl, and PI3K act upstream to NF-κB in response to shear stress. This Flk-1/Cbl/PI3K/NF-κB signaling pathway may be originated from integrins and transmitted by key tyrosine kinases and actin cytoskeleton. These results shed new lights on the molecular mechanism by which mechanical shear stress activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, which is critical for vascular inflammatory responses and atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Shear stress, Flk-1, Cbl, PI3K, NF-κB, Actin, Tyrosine kinases

INTRODUCTION

Vascular endothelial cells (ECs) are continuously exposed to mechanical stimuli (e.g., the shear stress resulting from blood flow), which play an important role in circulatory regulation in health and disease.12 Atherosclerotic lesions, which are characterized by the patchy deposit of fatty materials in the arterial walls and the subsequent reduced/blocked blood flow, occur preferentially at vascular curvatures and branch sites where the vessel walls are exposed to disturbed flow but not at the straight parts of vessels where laminar flow dominates.11 It has been well documented that shear stress can activate a variety of signaling cascades and gene expressions to modulate EC functions and pathophysiological processes, including atherosclerosis.4,14,26 A wide range of signaling and structural molecules, including the plasma membrane,7,38 membrane proteins/receptors such as integrins19,40 and VEGF receptor 2 (Flk-1),8,44 and cytoskeletal filaments25 have been shown to play important roles in mechanotransduction, i.e., transducing shear stress into biochemical signaling cascades. However, there is a need to further elucidate the molecular mechanism by which cells perceive and subsequently transduce shear stress into intracellular molecular activities to modulate pathophysiological processes such as atherosclerosis.

NF-κB, which belongs to the NF-κB/REL transcription factor family and plays important roles in vascular inflammatory responses,9,32 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by the inhibitor of κB protein (IκB). Pro-inflammatory stimuli, e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, activate IκB kinase (IKK) to phosphorylate IκB.2,21 The phosphorylated IκB subsequently undergoes polyubiquination and degradation to release NF-κB for its translocation into the nucleus to promote the expression of multiple genes,2,21 and the up-regulation of inflammatory genes such as NF-κB can be atherogenic.32 Shear stress has been shown to activate NF-κB in the endothelium.3,24 Our previous studies have shown that this shear-induced NF-κB is mediated by integrins.3 We have further shown that the membrane receptors integrin and Flk-1 can interact with each other upon shear application, with integrins acting upstream to Flk-1.44 The resultant activation and phosphorylation of Flk-1 can then recruit an adapter protein, Cbl,3 which regulates downstream signaling events.30,36 Upon shear stimulation, both Flk-1 and Cbl were shown to regulate Akt (protein kinase B) and subsequently IKK,43 an upstream molecule for NF-κB.33,34 Therefore, it is expected that shear stress can regulate NF-κB via the Flk-1/Cbl pathway. However, it has not been established as to how the integrin signaling can be transmitted to Flk-1 to activate the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In this work, we first confirmed the roles of Flk-1 and Cbl in the shear stress-induced activation of NF-κB and its translocation into the nucleus. We extended our study to show that PI3K, a molecule acting in between Cbl and Akt, is also essential for the shear-induced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that actin cytoskeleton and key tyrosine kinases in the adhesion complex, including Src family kinases and FAK, are involved in the shear-induced activation of NF-κB. Therefore, our results established the expected roles of Flk-1 and Cbl in regulating the shear-induced NF-κB activation, demonstrated that PI3K acts between Cbl and Akt in the signaling pathway, and identified actin cytoskeleton and integrin-associated tyrosine kinases as the mediators transmitting the shear-activated integrin signals to Flk-1/Cbl and subsequently NF-κB. Together with our previous findings, our current results indicate that shear stress regulates NF-κB via the activation of the membrane receptor Flk-1 to recruit the adapter protein Cbl for the subsequent activation of PI3K and Akt. The shear-induced signaling initiated from integrins is transmitted by integrin-associated tyrosine kinases and the actin cytoskeleton to modulate the Flk-1/Cbl/PI3K/NF-κB pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Cell culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO BRL (Grand Island, New York, USA). Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were isolated from bovine aorta with collagenase and cultured in a humidified 95% air, 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The culture medium was Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 unit/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. All experiments were conducted with BAEC cultures prior to passage 10 as previously described.3

Shear Stress Experiments

A parallel-plate flow system was used to impose shear stress on the cultured ECs as described by Frangos et al.17 In all experiments, BAECs were starved for 12 h in 0.5% serum followed by 2 h in serum-free medium before being subjected to shear stress (12 dyn/cm2).

DNA Plasmids and Transient Transfection

A hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged wild type Cbl (HA-Cblwt) and an HA epitope-tagged negative mutant of Cbl (HA-Cblnm) were gifts from Dr. Alexander Y. Tsygankov. In HA-Cblnm, tyrosine → phenylalanine mutations were introduced at positions 700, 731, and 774, which are the major tyrosine phosphorylation sites of c-Cbl.16 HIV(LTR)-Luc encodes a luciferase reporter driven by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) long terminal repeat (LTR) that contains two binding sites for NF-κB.31 The pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid contains a β-galactosidase gene driven by the SV40 promoter and enhancer. The various plasmids were transfected into BAECs at 80% confluence using the lipofectamine method as described by the vendor (GIBCO BRL).

Luciferase Activity Assay

HA-Cblwt or HA-Cblnm were cotransfected with HIV(LTR)-Luc and the pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid into BAECs for the NF-κB transcriptional activation assays with HIV(LTR)-Luc to report NFκB activity and the pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid to monitor transfection efficiency. The luciferase and β-gal assays were conducted as described previously.3

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were polyclonal anti-Cbl, anti-Flk-1, and PY20 monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). For immunoprecipitation, the cells were scraped into a lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, and 10 μg/mL Leupeptin). The lysate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was immunoprecipitated with the appropriate antibodies and protein A-sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at 4 °C overnight. The immunoprecipitated complexes were washed and used for immunoblotting. After SDS-PAGE, proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin followed by incubation with the primary antibody in 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin. The bound primary antibodies were detected by using a goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the ECL detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Immunostaining and Fluorescence Microscopy

For the inhibition experiments, BAECs were pretreated for 1 h with DMSO as the control solvent or with 5 μM SU1498, 100 nM Wortmannin, 1 μM Cytochalasin D, 100 μM genistein, 10 μM PP2, or 20 μM AG82 (Sigma) to inhibit Flk-1, PI3K, actin filaments, tyrosine kinases, Src family kinases, or FAK kinase, respectively. The treated cells were subsequently subjected to flow application for 30 min. The translocation of NF-κB was then studied by immunostaining. In brief, confluent monolayers of BAECs were fixed in methanol at –20 °C for 5 min and incubated with 3% goat serum at 4 °C overnight. The specimens were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by incubation with the polyclonal anti-NF-κB p65 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect the distribution of NF-κB. The images were collected using a confocal microscopy system (MRC-1000, Bio-Rad) and analyzed using NIH Image and Microsoft Excel software.

Statistics

The various experiments were performed independently at least three times. Comparisons of results between two groups were performed by using unpaired two-tailed t-tests assuming unequal population variance. Multiple group comparisons were done with analysis of variance (ANOVA), and statistical significance among multiple groups was determined by using Dunnett's Method. p-Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

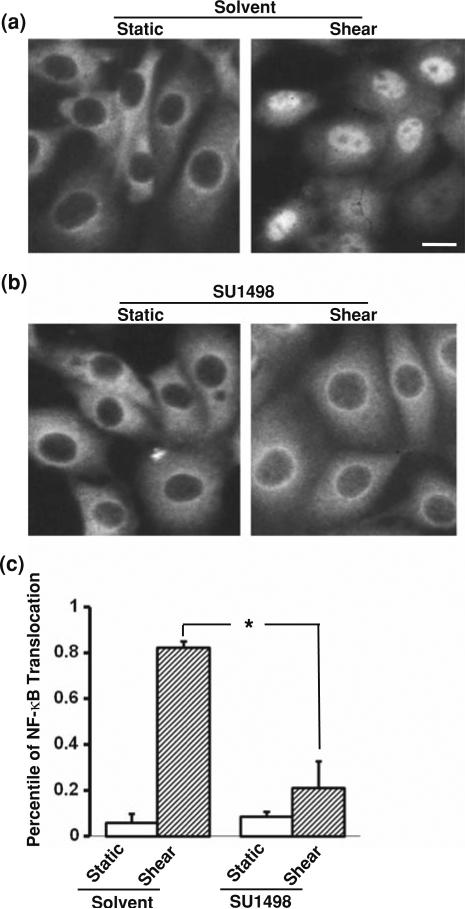

The Shear-Induced Translocation of NF-κB is Dependent on the Enzymatic Activity of Flk-1

We have previously shown that shear stress can induce the activation of NF-κB, which can be represented by the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus.3 This shear effect on NF-κB translocation is mediated by integrins.3 Since the shear-activated integrins were shown to transactivate Flk-1 which can regulate IKK, an upstream molecule of NF-κB,41,43,44 we asked whether Flk-1 can also mediate the shear-induced translocation of NF-κB. BAECs were subjected to various time periods of shear stress (12 dyn/cm2) or kept as static control. Fluorescence immunostaining revealed that p65 (a subunit of NF-κB) clearly translocated to the nucleus upon shear application as shown in the control groups treated with solvent vehicles (Fig. 1a). In contrast, SU1498, an inhibitor of Flk-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, blocked the translocation of p65 to the nucleus in response to shear stress (Fig. 1b). These results suggest that the enzymatic activity of Flk-1 is essential for the shear-induced NF-κB translocation.

FIGURE 1.

The shear-induced translocation of NF-κB is dependent on the enzymatic activity of Flk-1. (a) BAECs were treated with a control solvent 0.1% DMSO for 1 h before being subjected to shear stress (right) or kept under static incubation (left) for 30 min. (b) BAECs were treated with SU1498 (5 μM) for 1 h before being subjected to shear stress (right) or kept under static incubation (left) for 30 min. In both (a) and (b), immunostaining was performed after fixation with an anti-NF-κB p65 antibody, which was then probed with fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. The subcellular localization of NF-κB was visualized by the distribution of fluorescein. (c) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of the percentile of BAECs with NF-κB localization inside the nucleus. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the indicated groups (n = 3). Scale bar, 20 μm.

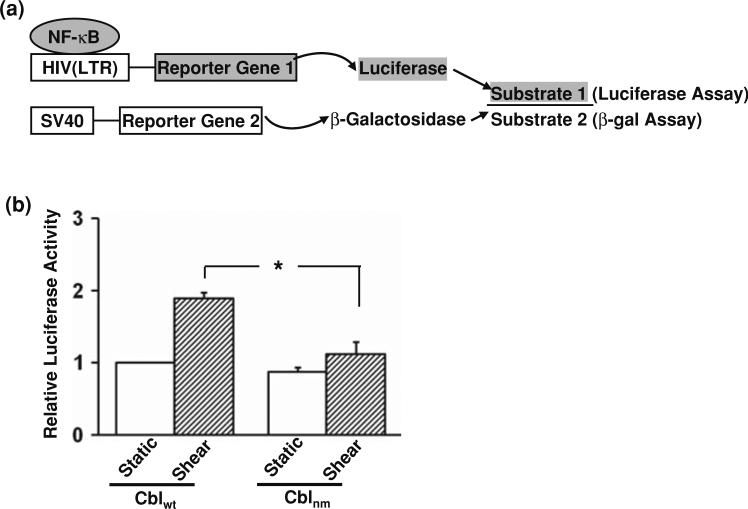

Cbl Mediates the Shear-Induced Activation of NF-κB

We then asked whether Cbl, which contains multiple protein docking sites and has been shown to bind to Flk-1 in regulating IKK upon shear application,43,44 is involved in the regulation of the shear-induced NF-κB activation. Since the activated NF-κB can translocate to the nucleus and serve as a transcription factor,2 the level of NF-κB binding to target promoters to activate gene expression was measured to represent the transcriptional activation of NF-κB. An HIV(LTR)-Luc construct, containing two repeats of NF-κB binding sites in the promoter region linked to a luciferase gene, was designed to report NF-κB transcriptional activity. The amount of luciferase produced can be quantitatively measured by the luciferase activity assay. A control reporter construct, pSV-β-galactosidase driven by SV40 promoter, was co-transfected with HIV(LTR)-Luc to quantify the transfection efficiency by measuring the production of β-galactosidase via a β-gal assay as previously described.3 The ratio of detected luciferase and β-galactosidase can hence represent a normalized NF-κB activity (Fig. 2a). HA-Cblwt (wild type Cbl) or HA-Cblnm (negative mutant of Cbl) was co-transfected with HIV(LTR)-Luc and pSV-β-galactosidase into BAECs before the application of flow. As shown in Fig. 2b, HA-Cblnm significantly inhibited the shear-induced NF-κB transcriptional activity. These results indicate that Cbl acts upstream to NF-κB signaling in response to shear stress.

FIGURE 2.

Cbl mediates the shear-activated NF-κB. (a) A cartoon scheme depicting the assays for measuring the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. HIV(LTR)-Luc and pSV-β-galactosidase were co-transfected into BAECs to report the transcriptional activity of NF-κB by luciferase production and the transfection efficiency for normalization by β-galactosidase production, respectively. The ratio of luciferase (measured by luciferase assay) to β-galactosidase (measured by β-gal assay) represents the normalized NF-κB activity. (b) HA-Cblwt or HA-Cblnm was co-transfected with HIV(LTR)-Luc and pSV-β-galactosidase into BAECs. The transfected cells were kept as static controls or subjected to shear stress for 8 h, followed by luciferase and β-galactosidase activity assays. The luminometer readings of luciferase activity were normalized for transfection efficiency by β-galactosidase activity. Bar graphs represent the normalized NF-κB transcriptional activity showing mean ± SEM from three separate experiments. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between groups as indicated.

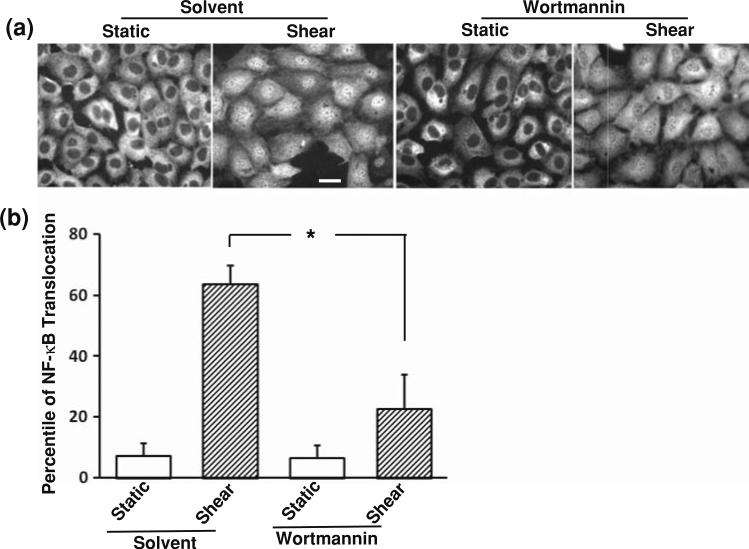

PI3K Mediates the Activation of NF-κB Induced by Shear Stress

Cblnm, which inhibited the shear-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 2b), has an impaired interface in binding to PI3K.16 Since PI3K is a major protein associated with Cbl and plays a role in regulating the NF-κB pathway,13 we hypothesized that PI3K may act downstream to Flk-1 and Cbl in mediating the shear-induced NF-κB activation. To examine the role of PI3K, BAECs were pretreated with a PI3K inhibitor, Wortmannin (100 nM), for 1 h before being subjected to various time periods of shear stress (12 dyn/cm2) or kept as static control. The fluorescence immunostaining revealed that Wortmannin significantly attenuated the shear-induced translocation of NF-κB (Fig. 3a). Quantification of the results and statistical analysis further confirmed the immunostaining observations (Fig. 3b). While Wortmannin clearly attenuated the shear-induced NF-κB translocation and can completely block the PI3K activity and the Akt activation in response to shear stress,5,22 it is of note that shear stress still caused a minor induction of NF-κB translocation in the presence of Wortmannin. These results indicate that the shear-induced translocation of NF-κB is mainly mediated by PI3K, although other signaling pathways may bypass PI3K in regulating NF-κB upon shear application.

FIGURE 3.

PI3K mediates the activation of NF-κB induced by shear stress. (a) BAECs were treated with Wortmannin (100 nM) or its control solvent 0.1% DMSO for 1 h before being subjected to shear stress or kept under static incubation for 30 min. After fixation, immunostaining was performed with an anti-NF-κB p65 antibody, which was then probed with fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. The subcellular localization of NF-κB was visualized by the distribution of fluorescein. (b) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of the percentile of BAECs with NF-κB localization inside the nucleus. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the indicated groups (n = 5). Scale bar, 20 μm.

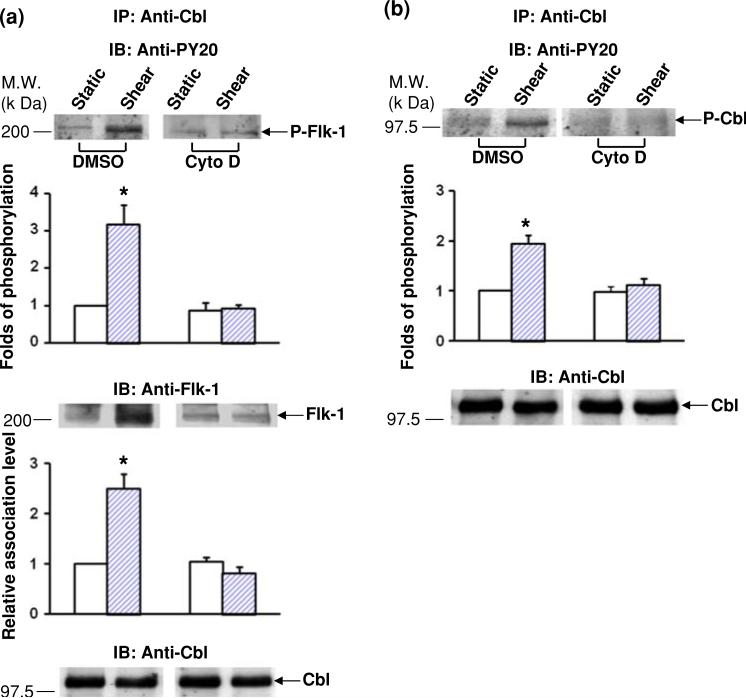

Actin Cytoskeleton is Essential for the Interaction Between Flk-1 and Cbl in Response to Shear Stress

It has been shown that integrins are crucial in mechanotransduction4 and mediate the shear-induced complex formation, and interaction between Flk-1 and Cbl.44 Since the actin-based cytoskeleton is closely linked to integrins and their associated focal adhesion complex,35 we tested the hypothesis that the integrity of the actin-based cytoskeleton is essential in mediating the transactivation from integrins to Flk-1 and its subsequent interaction with Cbl in response to shear stress. BAECs were pre-incubated with Cytochalasin D, which is a reagent that disrupts the actin filament network, or its solvent DMSO as control followed by the application of shear stress (12 dyn/cm2) for 5 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Cbl antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-PY20 and anti-Flk-1 antibodies to measure the degree of Flk-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and the amount of Cbl-bound Flk-1, respectively. Both the shear-induced tyrosine phosphorylation (top gel panel) and the amount of Cbl-bound Flk-1 (middle gel panel) were blocked by Cytochalasin D (Fig. 4a). We then examined the role of actin cytoskeleton on the subsequent Cbl tyrosine phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 4b, Cytochalasin D abolished the shear-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl. These results show that actin filaments are important for both the Flk-1-Cbl interaction and Cbl tyrosine phosphorylation in response to shear stress. Together with our previous study demonstrating that integrins mediate the shear-induced activation of Flk-1 and Cbl,44 these results indicate that the actin cytoskeleton may provide a link to transmit the signals between the two membrane receptors integrin and Flk-1 to regulate downstream molecular events, e.g., Cbl phosphorylation.

FIGURE 4.

Actin cytoskeleton is essential for the interaction between Flk-1 and Cbl in response to shear stress. (a) BAECs were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or Cytochalasin D (1 μg/mL) for 1 h. The treated cells were then subjected to shear stress or static incubation for 5 min. Cell lysates from the various samples were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-Cbl antibody, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with a PY20 anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (upper panel, arrow P-Flk-1), an anti-Flk-1 antibody (middle panel, arrow Flk-1), or an anti-Cbl antibody (lower panel, arrow Cbl). (b) BAECs were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or Cytochalasin D (1 μg/mL) for 1 h. The treated cells were then subjected to shear stress or static incubation for 5 min. The cell lysates were subjected to IP with an anti-Cbl antibody and IB with a PY20 anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (upper panel of gels) or an anti-Cbl antibody (lower panel of gels); the arrows represent the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl (P-Cbl) in the upper panel and total Cbl protein level in the lower panel. In both (a) and (b), bar graphs are densitometry analyses representing the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between the indicated groups and the untreated, static controls.

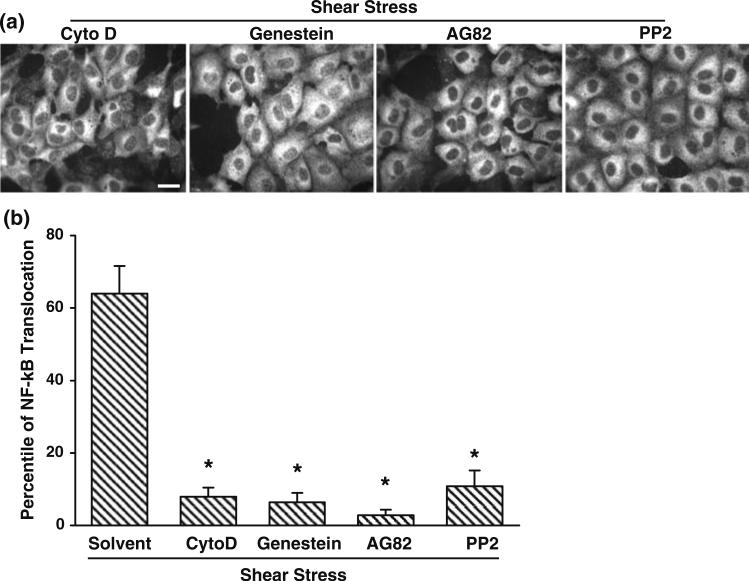

Actin Cytoskeleton, FAK, and Src Family Kinases at Focal Adhesions are Important for the Shear-Induced NF-κB Activation

Since the actin cytoskeleton is essential for the shear-induced Cbl phosphorylation (Fig. 4b), which may lead to the recruitment of PI3K and subsequent regulation of NF-κB, we further tested the role of the actin cytoskeleton in shear-induced NF-κB activation. BAECs were pretreated with Cytochalasin D for 1 h before being subjected to shear stress. As shown in Fig. 5, Cytochalasin D clearly abolished the shear-induced translocation of NF-κB (first image from left). In addition, since tyrosine kinases, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases, have been shown to play critical roles for the integrin-mediated focal adhesion dynamics and the actin-mediated mechanotransduction,20,25 we reasoned that these tyrosine kinases may be essential for the shear-induced NF-κB translocation. Indeed, genistein, AG82 or PP2, which inhibit general tyrosine kinases, FAK or Src family kinases, respectively, blocked the shear-induced NF-κB translocation (Fig. 5). These results confirmed that tyrosine kinases, including FAK and Src family kinases, play important roles in mediating the shear-induced NF-κB activation. Therefore, the integrin-mediated focal adhesion and its associated tyrosine kinase activities may transmit the mechanical cues via the actin cytoskeleton to activate the Flk-1/Cbl/PI3K pathway to regulate NF-κB signaling.

FIGURE 5.

Actin cytoskeleton and tyrosine kinases at focal adhesions are important for the shear-induced NF-κB activation. BAECs were treated with Cytochalasin D (1 μM), Genistein (100 μM), AG82 (20 μM), or PP2 (10 μM) for 1 h before being subjected to shear stress for 30 min. (a) After fixation, immunostaining was performed with an anti-NF-κB p65 antibody followed by fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG. The subcellular localization of NF-κB was visualized by the distribution of fluorescein. (b) Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM of the percentile of BAECs with NF-κB localization inside the nucleus. * p < 0.05 vs. solvent (n = 3). Scale bar, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

Vascular ECs are continuously exposed to mechanical forces, including shear stress. Remarkable progress has been made in advancing our understanding on how these mechanical forces can modulate EC functions.10 NF-κB in ECs is sensitive to mechanical stimulation and has been shown to play critical roles in inflammatory responses and atherosclerosis.9,32 Our previous results suggested that shear stress can activate integrins to regulate NF-κB.3 The shear-activated integrins was also shown to transactivate Flk-1, which recruits Cbl to regulate the downstream molecules Akt and IKK.43,44 While it is likely that Flk-1 and Cbl are involved in the shear-induced NF-κB activation, it was unclear as to how the integrin signaling is transmitted to Flk-1. The results in the current paper indicate that key integrin-associated tyrosine kinases, actin cytoskeleton, and the Flk-1/Cbl/PI3K pathway play important roles in regulating the shear-induced activation of NF-κB. This study also shows that actin cytoskeleton plays a critical role in mediating the interaction between Flk-1 and Cbl in response to shear stress.

Integrins and their associated cytoskeleton have been well documented to play important roles in mechanotransduction.1,44 Our previous findings suggest that integrins can transactivate Flk-1 and its associated adapter protein Cbl upon shear stimulation.44 In this report, we have further shown that the actin cytoskeleton plays a significant role in mediating this transactivation. Thus, the disruption of actin filaments by Cytochalasin D blocked the shear-induced Flk-1 and Cbl interaction, as well as the Cbl phosphorylation (Fig. 4), though we cannot rule out the possibility that these effects may be mediated via blocking the integrin-dependent phosphorylation of Flk-1. Cytochalasin D also inhibited the shear-induced signaling event of NF-κB activation, downstream of Flk-1 and Cbl (Fig. 5). Interestingly, inhibition of FAK and Src family kinases, the key tyrosine kinases involved in the integrin-mediated focal adhesion dynamics, blocked the shear-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 5). Integrin engagement has been shown to activate FAK via its FERM domain,29 with FAK undergoing a conformational change to expose its kinase domain, which subsequently auto-phosphorylates the intramolecular Y397 site.27 This phosphorylated Y397 can provide a docking site to recruit Src family kinases via their SH2 domain to the focal adhesion sites.39 The localized Src family kinases can phosphorylate actin-interacting molecules, including cortactin, to regulate the connection between focal adhesion sites and actin cytoskeleton.39 Therefore, FAK and Src family kinases may provide a regulation mechanism that connects integrins to actin network, which can then transmit the mechanical impact to Flk-1 and Cbl. Indeed, it has been well documented that the actin-based cytoskeleton can transmit biochemical signals to allow fast responses when cells are exposed to mechanical stimulation.18,42 Several reports indicate that integrins can form physical complexes with receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) such as Flk-1.6,37 This association between integrins and Flk-1 may also depend on the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton. Both integrin αvβ3 and an activated RTK, PDGFR-β, have been shown to associate with a cytoskeletal (NP-40 insoluble) fraction in the PDGF-stimulated human foreskin fibroblasts.35 It is possible that the actin cytoskeleton is required in mechanotransduction by providing the structural connection and support, as well as organizing the spatial distribution of signaling molecules. The assessment of the internal structure of the cell using cytoskeletal depolymerization agents via a microfluidics system may directly address this question at the subcellular level.23

Both Flk-1 and Cbl appear essential for the NF-κB activation in response to shear stress (Figs. 1 and 2), consistent with the expectation based on our previous findings that integrins not only mediate the shear-activated NF-κB, but also transactivate Flk-1 to regulate Cbl and subsequently IKK.3,43,44 It is possible that shear stress, via integrins and actin network, can cause changes in the conformation and localization of Flk-1, thus altering the clustering and autophosphorylation of Flk-1. The phosphorylated cytoplasmic tail of Flk-1 can then recruit Cbl directly through its PTB domain or indirectly through other adapter proteins such as Grb2 and Shc, which are known to associate with Flk-1.33 The receptor-bound Cbl can then undergo phosphorylation and recruit signaling molecules such as PI3K. Indeed, the phosphorylated tyrosine 731 of Cbl is a binding site for p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3K.28

While it has been well established that PI3K regulates NF-κB signaling,33,34 the detailed molecular mechanism linking PI3K and NF-κB is not clear. One possibility is that the activated PI3K can produce PIP3 at the plasma membrane which recruits Akt via its pleckstrin homology domain.15 This membrane localization of Akt will allow its interaction with the upstream phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK) to lead to Akt activation.45 The subsequent complex formation between Akt and IKK can then cause the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB and the subsequent nuclear translocation of NF-κB for transcriptional activation.33,34

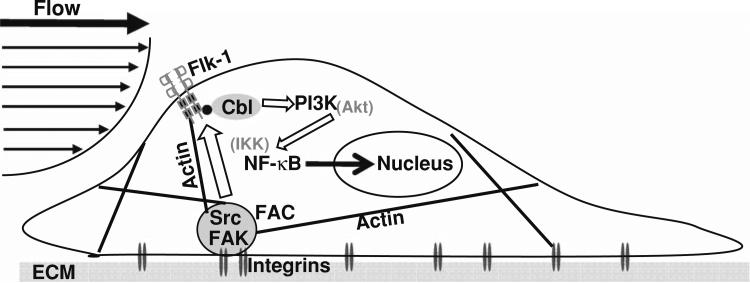

In summary, our results demonstrate that shear stress regulates the NF-κB activation via a pathway in which signals are transmitted from integrins, via FAK and Src family kinases at focal adhesions and actin cytoskeleton, to activate Flk-1, followed by Cbl and PI3K (see Fig. 6 for illustration). These results help advance our understanding on how ECs coordinate intracellular signaling molecules to adjust and respond to external mechanical cues in health and disease, e.g., atherosclerosis.

FIGURE 6.

A schematic cartoon depicting the potential molecular mechanism by which shear stress regulates the activity of NF-κB. Shear stress acts on integrins to turn on the Flk-1/Cbl complex via the actin network. The subsequently phosphorylated Cbl can recruit PI3K, which eventually leads to the translocation of NF-κB and the induction of transcriptional activity. The block arrows represent the signaling transduction between different molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is part of the celebration dedicated to Dr. Van C. Mow's 70th birthday, for his outstanding leadership and marvelous contributions in the field of biomechanics and mechanobiology. We thank Dr. Alexander Y. Tsygankow (Temple University) for providing HA-Cblwt, and HA-Cblnm. This work was supported in part by NIH research Grants HL080518, HL085195, and HL064382 (S. Chien), NCI139272, NSF0846429, and the Beckman Laser Institute, Inc. (Y. Wang).

Footnotes

Y. Wang, L. Flores contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alenghat FJ, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction: all signals point to cytoskeleton, matrix, and integrins. Sci. STKE. 2002:PE6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.pe6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin AS., Jr. The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhullar IS, Li YS, Miao H, Zandi E, Kim M, Shyy JY, Chien S. Fluid shear stress activation of I kappaB kinase is integrin-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30544–30549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boo YC, Jo H. Flow-dependent regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: role of protein kinases. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C499–C508. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00122.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, Du J, Jo H. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borges E, Jan Y, Ruoslahti E. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 bind to the beta 3 integrin through its extracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39867–39873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler PJ, Norwich G, Weinbaum S, Chien S. Shear stress induces a time- and position-dependent increase in endothelial cell membrane fluidity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C962–C969. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen KD, Li YS, Kim M, Li S, Yuan S, Chien S, Shyy JY. Mechanotransduction in response to shear stress. Roles of receptor tyrosine kinases, integrins, and Shc. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:18393–18400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LF, Greene WC. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien S. Mechanotransduction and endothelial cell homeostasis: the wisdom of the cell. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H1209–H1224. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008;36:554–562. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chien S, Li S, Shyy YJ. Effects of mechanical forces on signal transduction and gene expression in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 1998;31:162–169. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi BH, Kim CG, Lim Y, Shin SY, Lee YH. Curcumin down-regulates the multidrug-resistance mdr1b gene by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/NF kappa B pathway. Cancer Lett. 2008;259:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies PF, Spaan JA, Krams R. Shear stress biology of the endothelium. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005;33:1714–1718. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feshchenko EA, Langdon WY, Tsygankov AY. Fyn, Yes, and Syk phosphorylation sites in c-Cbl map to the same tyrosine residues that become phosphorylated in activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:8323–8331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frangos JA, Eskin SG, McIntire LV, Ives CL. Flow effects on prostacyclin production by cultured human endothelial cells. Science. 1985;227:1477–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.3883488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalali S, del Pozo MA, Chen K, Miao H, Li Y, Schwartz MA, Shyy JY, Chien S. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction requires its dynamic interaction with specific extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:1042–1046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031562998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalali S, Li YS, Sotoudeh M, Yuan S, Li S, Chien S, Shyy JY. Shear stress activates p60src-Ras-MAPK signaling pathways in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998;18:227–234. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karin M, Delhase M. JNK or IKK, AP-1 or NF-kappaB, which are the targets for MEK kinase 1 action? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:9067–9069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klingler-Hoffmann M, Bukczynska P, Tiganis T. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling negates the growth advantage imparted by a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor on human glioblastoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;105:331–339. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, LeDuc PR. Dissecting the molecular basis of the mechanics of living cells. Exp. Mech. 2009;49:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lan Q, Mercurius KO, Davies PF. Stimulation of transcription factors NF kappa B and AP1 in endothelial cells subjected to shear stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;201:950–956. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Kim M, Hu YL, Jalali S, Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T, Chien S, Shyy JY. Fluid shear stress activation of focal adhesion kinase. Linking to mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30455–30462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YS, Haga JH, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 2005;38:1949–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lietha D, Cai X, Ceccarelli DF, Li Y, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of focal adhesion kinase. Cell. 2007;129:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao H, Yuan S, Wang Y, Tsygankov A, Chien S. Role of Cbl in shear-activation of PI 3-kinase and JNK in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;292:892–899. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitra SK, Schlaepfer DD. Integrin-regulated FAK-Src signaling in normal and cancer cells. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyake S, Lupher ML, Jr., Andoniou CE, Lill NL, Ota S, Douillard P, Rao N, Band H. The Cbl protooncogene product: from an enigmatic oncogene to center stage of signal transduction. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1997;8:189–218. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i2-3.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabel G, Baltimore D. An inducible transcription factor activates expression of human immunodeficiency virus in T cells. Nature. 1987;326:711–713. doi: 10.1038/326711a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orr AW, Hahn C, Blackman BR, Schwartz MA. p21-activated kinase signaling regulates oxidant-dependent NF-kappa B activation by flow. Circ. Res. 2008;103:671–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfeffer SR, Pfeffer LM, Donner DB. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romashkova JA, Makarov SS. NF-kappaB is a target of AKT in anti-apoptotic PDGF signalling. Nature. 1999;401:86–90. doi: 10.1038/43474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneller M, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Alphavbeta3 integrin associates with activated insulin and PDGFbeta receptors and potentiates the biological activity of PDGF. EMBO J. 1997;16:5600–5607. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smit L, Borst J. The Cbl family of signal transduction molecules. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 1997;8:359–379. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i4.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soldi R, Mitola S, Strasly M, Defilippi P, Tarone G, Bussolino F. Role of alphavbeta3 integrin in the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. EMBO J. 1999;18:882–892. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thi MM, Tarbell JM, Weinbaum S, Spray DC. The role of the glycocalyx in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton under fluid shear stress: a “bumper-car” model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci .USA. 2004;101:16483–16488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tzima E, del Pozo MA, Shattil SJ, Chien S, Schwartz MA. Activation of integrins in endothelial cells by fluid shear stress mediates Rho-dependent cytoskeletal alignment. EMBO J. 2001;20:4639–4647. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Botvinick EL, Zhao Y, Berns MW, Usami S, Tsien RY, Chien S. Visualizing the mechanical activation of Src. Nature. 2005;434:1040–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature03469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Chang J, Li YC, Li YS, Shyy JY, Chien S. Shear stress and VEGF activate IKK via the Flk-1/ Cbl/Akt signaling pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;286:H685–H692. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00237.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Miao H, Li S, Chen KD, Li YS, Yuan S, Shyy JY, Chien S. Interplay between integrins and FLK-1 in shear stress-induced signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1540–C1547. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00222.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wymann MP, Pirola L. Structure and function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1436:127–150. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]