Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is caused by functional and structural changes in the pulmonary vasculature, leading to increased pulmonary vascular resistance. The process of pulmonary vascular remodeling is accompanied by endothelial dysfunction, activation of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, crosstalk between cells within the vascular wall, and recruitment of circulating progenitor cells. Recent findings have reestablished the role of chronic vasoconstriction in the remodeling process. Although the pathology of PAH in the lung is well known, this article is concerned with the cellular and molecular processes involved. In particular we focus on the role of the Rho family guanosine triphosphatases in endothelial function and vasoconstriction. The crosstalk between endothelium and vascular smooth muscle is explored in the context of mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor, alterations in angiopoietin-1/TIE2 signaling and the serotonin pathway. We also review the role of voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channels and transient receptor potential channels in the regulation of cytosolic [Ca2+] and [K+], vasoconstriction, proliferation and cell survival. We highlight the importance of the extracellular matrix as an active regulator of cell behavior and phenotype and evaluate the contribution of the glycoprotein tenascin-c as a key mediator of smooth muscle cell growth and survival. Finally, we discuss the origins of a cell type critical to the process of pulmonary vascular remodeling, the myofibroblast, and review the evidence supporting a contribution for the involvement of endothelial-mesenchymal transition and recruitment of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells.

Keywords: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, Cellular, Molecular Basis

Introduction

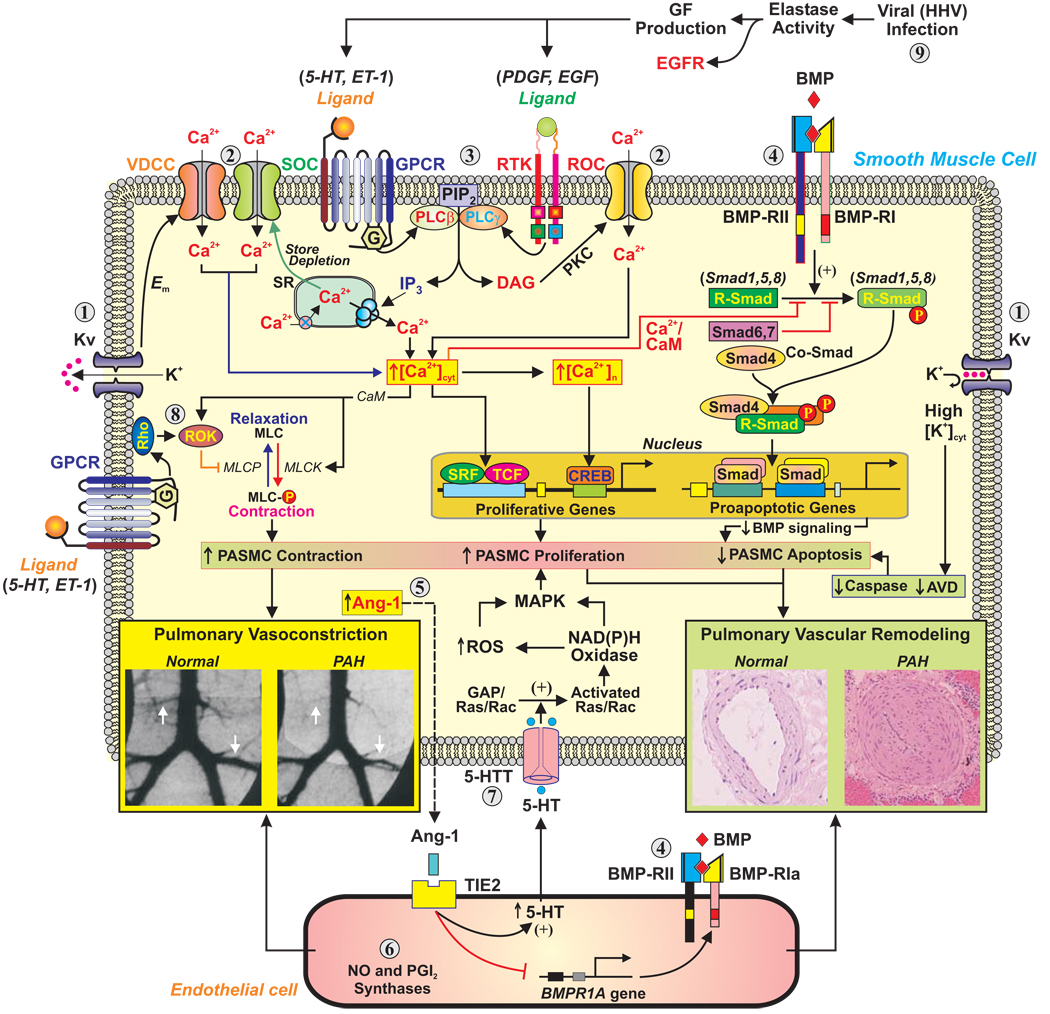

Despite the recognized success of existing drug interventions in the relief of symptoms of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), and possibly improvement in survival, most patients eventually become resistant to therapy and succumb to the disease. The past few years have seen a remarkable increase in our knowledge of the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the pathobiology of PAH. This summary aims to present the current state of our understanding of some of the key mechanisms (Figure 1). We also indicate further areas and directions of research and suggest novel approaches to therapy.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting potential mechanisms involved in the development of PAH.

AVD=apoptotic volume decrease; CaM=calmodulin; DAG=diacylglycerol; Em=membrane potential; EGF=epidermal growth factor; GPCR=G protein-coupled receptor; HHV=human herpes virus; IP3=inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; MLC=myosin light chain; MLCK=myosin light chain kinase; PDGF=platelet-derived growth factor; PKC=protein kinase C; PLC=phospholipase C; ROS=reactive oxygen species; RTK=receptor tyrosine kinase; SR=sarcoplasmic reticulum.

Endothelial Dysfunction in PAH

Endothelial cells (ECs) are recognized as major regulators of vascular function, and endothelial dysfunction has come to mean a multifaceted imbalance in EC production of vasoconstrictors versus vasodilators, activators versus inhibitors of smooth muscle cell (SMC) growth and migration, prothrombotic versus antithrombotic mediators, and proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory signals.

Rho guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) in endothelial dysfunction

Rho (Ras homologous) GTP-binding proteins regulate many cellular processes, including gene transcription, differentiation, proliferation, hypertrophy, apoptosis, phagocytosis, adhesion, migration, and contraction (1). In the prototypical mechanism of RhoA GTPase signaling, environmental cues, acting through G protein-coupled receptors or receptor-dependent and independent tyrosine kinases, activate guanine nucleotide exchange factors, which induce exchange of GDP for GTP binding and translocation of GTP-RhoA to the plasma membrane. The membrane translocation requires posttranslational prenylation. Upon translocation to the plasma membrane, GTP-RhoA activates its effectors, including the two isoforms of ROCK, ROCK I (ROKβ) and ROCK II (ROKα). Negative regulators of RhoA activation include guanine nucleotide disassociation inhibitors, which oppose the exchange of GTP for GDP; GTPase activating proteins, which catalyze dephosphorylation and inactivation of membrane-bound GTP-RhoA; statins, which inhibit isoprenylation of RhoA and thereby prevent translocation of GTP-RhoA to the cell membrane (2); and protein kinases A and G, which, by phosphorylating RhoA, also prevent membrane translocation of the GTP-bound protein (3).

Rho GTPases and EC permeability

An increase in EC permeability may be an important component of the pathogenesis of PAH. The GTPases RhoA and Rac1 play opposing roles in the regulation of EC barrier function. While stimuli such as thrombin activate RhoA/ROCK, which increases formation of F-actin stress fibers, cell contraction, and permeability, barrier enhancing mediators such as sphingosine-1-phosphate and PGI2 stimulate Rac1/PAK, which counteracts the effects of RhoA/ROCK and promotes cortical F-actin ring formation and barrier integrity (4). Pulmonary artery ECs cultured from chronically hypoxic piglets demonstrate low Rac1 and high RhoA activities, which correlate with increased stress fiber formation and permeability (5). Activation of Rac1/PAK-1 and inhibition of RhoA reverse these changes.

Rho GTPases and EC proliferation, migration, and apoptosis

Rho GTPases participate in EC proliferation and apoptosis. Interestingly, the hyperproliferative, apoptosis-resistant phenotype of PAH ECs may be due to persistent activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (6), a downstream target of Rho GTPases. STAT3 mediates RhoA-induced nuclear factor (NF)-κB and cyclin D1 transcription and is involved in NF-κB nuclear translocation (7).

Role of rho GTPases in thrombosis

In situ thrombosis of small peripheral pulmonary arteries contributes to PAH. ECs are directly involved in the fibrinolytic process through synthesis and release of the profibrinolytic tissue plasminogen activator and the antifibrinolytic/ prothrombotic plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). The stimulation of systemic artery EC PAI-1 expression by angiotensin II, C-reactive protein, high glucose, and monocyte adhesion is dependent on activation of RhoA/ROCK signaling. Similarly, EC expression of tissue factor, another prothrombotic mediator, increased in the pulmonary arteries (PAs) of PAH lungs, is upregulated by RhoA/ROCK signaling (8). The RhoA/ROCK and Rac/PAK signaling pathways are implicated in thrombin- and TXA2-induced platelet activation and aggregation (9).

Nitric Oxide (NO) and Prostacyclin (PGI2)

Endothelial dysfunction in PAH is reflected by reduced production of the vasodilators/growth inhibitors NO and PGI2 and increased production of the vasoconstrictor/co-mitogens, eg, endothelin-1 and thromboxane A2. NO signaling is mediated mainly by the guanylate cyclase/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway. Degradation of the second messenger of NO, cGMP, by phosphodiesterases is mainly accomplished by PDE5.

Reduced NO bioavailability in PAH can be due to decreased expression of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), inhibition of eNOS enzymatic activity, and inactivation of NO by superoxide anion. Activation of endothelial RhoA/ROCK signaling can be involved in at least the first two processes. For example, RhoA/ROCK activation mediates hypoxia- and thrombin-induced inhibition of both eNOS expression and its activity in cultured ECs (10). The activity of arginase II, which reduces NO synthesis by competing with eNOS for the substrate L-arginine, is increased in PAH ECs (11), and RhoA/ROCK signaling mediates thrombin- and TNF-α/lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of eNOS (12). Patients with idiopathic PAH (IPAH) have increased plasma levels of the endogenous inhibitor of eNOS, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) (13), and the levels of ADMA and the enzyme that degrades it, dimethylarginine dimethyaminohydrolase (DDAH2), are, respectively, increased and decreased in the PA endothelium of IPAH patients (13).

PGI2 stimulates the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which also inhibits the proliferation of SMCs and decreases platelet aggregation. A deficiency of PGI2 and PGI2 synthase and an excess of thromboxane are found in PAH (14). Moreover, PGI2-receptor knockout mice develop more severe hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (PH) (15). Conversely, PGI2 overexpressing mice are protected against hypoxia-induced PH (16).

Angiopoietin and TIE-2

Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) is an oligomeric secreted glycoprotein, which, along with angiopoietin-2 and angiopoietin-3/4, comprises a family of growth factors. The angiopoietin ligands exert their effects through the endothelial-specific tyrosine kinase, TIE2 (17). During lung development, both Ang-1 and TIE2 are expressed in growing blood vessels: Ang-1 is made and secreted by vascular SMCs and pericytes, whereas TIE2 is a transmembrane receptor expressed on endothelial cells (18). In the adult, Ang-1 expression in the lung is minimal, whereas TIE2 expression remains constitutive (19).

Several lines of evidence suggest that Ang-1 regulates pathologic SMC hyperplasia in PAH. Ang-1 is overexpressed in most forms of nonfamilial PAH (18,20). In PAH, Ang-1 causes activation of the TIE2 receptor by tyrosine autophosphorylation in the pulmonary vascular endothelium (20,21). Enhanced TIE2 levels and a 4-fold increase in TIE2 phosphorylation are found in human PAH lung tissue, compared with control subjects (20,22).

Virally-mediated overexpression of Ang-1 in the rat lung results in PH (21,23). Ang-1 transgenic animals show increased pulmonary vascular endothelial TIE2 phosphorylation and SMC hyperplasia in small pulmonary arterioles. Further, overexpression of a soluble TIE2 ectodomain, which sequesters Ang-1, suppresses the pulmonary hypertensive phenotype in monocrotaline and Ang-1–induced models of this disease (24).

There is a reciprocal relationship between bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR) 1A and Ang-1 expression in the lungs of patients with nonfamilial PAH (20). Ang-1 downregulates BMPR1A expression through a TIE2 pathway in human PAECs. Stimulation of human PAECs with Ang-1 induces release of serotonin (5-HT), a potent stimulator of SMC proliferation (21,22). There is controversy in this field. In contrast to a causative role, Ang-1 has been reported to protect against the development of PAH in the rat monocrotoline and hypoxia models of disease (25).

The SMC in PAH

5-HT, serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and receptors

Patients with IPAH have increased circulating 5-HT levels, even after heart-lung transplantation (26). In contrast to the constricting action of 5-HT on SMCs, which is mainly mediated by 5-HT receptors 1B/D, 2A, and 2B (27), the mitogenic and co-mitogenic effects of 5-HT require internalization via 5-HTT (28). This may require co-stimulation of the 5HT1B receptor (29). Drugs that competitively inhibit 5-HTT block the mitogenic effects of 5-HT on SMCs (30). The appetite suppressants fenfluramine, d-fenfluramine, and aminorex differ from selective 5-HTT inhibitors in that they not only inhibit 5-HT reuptake but also trigger indoleamine release and interact with 5-HTT and 5-HT receptors in a specific manner (30).

5-HTT

5-HTT is abundantly expressed on PASMCs (31). Mice with targeted 5-HTT gene disruption develop less severe hypoxic PH than wild-type controls (32,33). Conversely, increased 5-HTT expression is associated with increased severity of hypoxic PH (34,35). Indeed specific overexpression of 5-HTT in PASMCs is sufficient to produce spontaneous PH (33).

5-HT receptors in PH

Of the 14 distinct 5HT receptors, the 5HT2A, 5HT2B and 5HT1B receptors are particularly relevant to PAH.

The 5HT2A receptor. In most nonhuman mammals, the 5HT2A receptor mediates vasoconstriction in both the systemic and pulmonary circulations (36). However, the 5HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin is not specific for the pulmonary circulation, and systemic effects have limited its use in PAH, where it fails to improve pulmonary hemodynamics significantly (37).

The 5HT2B receptor. The development of hypoxia-induced PH in mice is ablated in 5-HT2B-receptor knockout mice (38), and this receptor may control 5-HT plasma levels in mice. However, the 5HT2B receptor may also mediate vasodilation of the PA (39), and loss of the 5HT2B receptor function may predispose to fenfluramine-associated PH in man (40).

The 5HT1B-receptor. The 5HT1B-receptor mediates constriction in human PAs (41) and plays a role in the development of PAH (36,42), since inhibition, either by genetic knockout or pharmacologic antagonism, reduces hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling (36). There is cooperation between the 5-HT1B-receptor and the 5-HTT in mediating pulmonary vascular contraction (43). In addition, 5HT1B-receptor expression is increased in mice overexpressing the human 5-HTT and in the fawn-hooded rat (FHR), which also demonstrates increased 5-HTT expression (43). Both these models are predisposed to hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling. Remodeled PAs from patients with PAH overexpress the 5HT1B-receptor. 5HT1B-receptor–mediated changes are specific to the pulmonary circulation, making this receptor an attractive therapeutic target for PH.

5-HT synthesis in PH

The rate-limiting step in 5-HT biosynthesis is catalyzed by the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase (Tph). Although peripheral 5-HT is synthesized chiefly by the enterochromaffin cells in the gut, human PAECs produce 5-HT and express the Tph1 isoform. Both 5-HT synthesis and Tph1 expression are increased in cells from patients with IPAH compared with controls (44). Mice lacking Tph1 are resistant to hypoxia- and dexfenfluramine-induced PH (45,46).

K+ and Ca+ Channels in PAH

In PASMCs, the free Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol ([Ca2+]cyt) is an important determinant of contraction, migration, and proliferation. [Ca2+]cyt in PASMCs can be increased by (a) Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, receptor-operated Ca2+ channels (ROC), and store-operated Ca2+ channels, and (b) Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (eg, sarcoplasmic reticulum [SR]) via Ca2+ release channels (eg, IP3 receptors and ryanodine receptors). Inward transport of Ca2+ via Ca2+ transporters in the plasma membrane, such as the reverse mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, is also an important pathway for increasing [Ca2+]cyt. In contrast, [Ca2+]cyt in PASMCs can be decreased by (a) Ca2+ extrusion by the Ca2+ -Mg2+ ATPase (Ca2+ pump) and by the forward mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in the plasma membrane; and (b) Ca2+ sequestration by the Ca2+ -Mg2+ ATPase in the SR (SERCA).

Inhibition of K+ channel activity

Decreased expression and/or function of K+ channels leads to membrane depolarization and contributes to sustained elevation of [Ca2+]cyt by (a) activating VDCC, (b) facilitating the production of IP3, which stimulates the release of SR Ca2+ into the cytoplasm, and (c) promoting Ca2+ entry via the reverse mode of Na+/Ca2+ exchange.

The role of receptor-operated and store-operated Ca2+ channels in regulating [Ca2+]cyt

The influx of Ca2+ through SOC channels, referred to as capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE), is critical for refilling the empty SR with Ca2+. SOCs in vascular SMC include the transient receptor potential channels. Some canonical TRP (TRPC) channel genes are expressed in human PASMCs and PAECs.

PASMC proliferation is associated with a significant increase in mRNA and protein expression of TRPC channels such as TRPC1, TRPC3 and TRPC6 (47,48). Inhibition of TRPC expression with antisense oligonucleotides markedly decreases the amplitude of CCE and significantly inhibits PASMC proliferation. Thus upregulation of TRPC channels may be a significant mechanism in the induction of PASMC proliferation.

Pathogenic role of downregulated Kv channels and upregulated TRP channels

In PASMCs from IPAH patients, the amplitude of whole-cell IK(V) and mRNA/protein expression levels of Kv channel subunits (eg, Kv1.2 and Kv1.5) are both significantly decreased in comparison with cells from controls or patients with secondary PH (49). The downregulated Kv channels and decreased IK(V) are associated with a more depolarized Em in IPAH PASMCs, and the resting [Ca2+]cyt is much higher than in PASMCs from controls. The magnitude of CCE, evoked by passive store depletion with CPA, is significantly greater in PASMCs from IPAH patients than in cells from secondary PH patients. Enhanced CCE, possibly via upregulation of TRPC channels may represent a critical mechanism involved in the development of severe PAH.

Kv channels, mitochondrial metabolism and PAH

Otto Warburg proposed that a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, occurring despite adequate oxygen availability, was a characteristic of cancers (50). Recent data suggest that PAH and cancer share this “Warburg phenotype (51,52).” Both are characterized by mitochondrial hyperpolarization, depressed pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity, and depressed H2O2 production (53). In both there is also an O2-independent perpetuation of the rapid, reversible metabolic/redox shifts that normally occur in response to hypoxia and initiate hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (54,55). This metabolic shift creates a “pseudohypoxic environment” with glycolytic predominance and normoxic hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α activation. The metabolic shift suppresses Kv1.5 expression, leading to membrane depolarization and elevation of cytosolic K+ and Ca2+. In both PAH PASMCs and cancer cell lines, this creates a proliferative, apoptosis-resistant phenotype.

As in familial PAH, PAH in the FHR is heritable. The FHR’s PASMC mitochondrial reticulum is fragmented even before PAH develops. The observed hyperpolarization of ΔΨm and reduction in production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) also occurs in PASMCs from IPAH patients (51). In PAH, mitochondrial abnormalities that shift metabolism away from oxidative phosphorylation toward glycolysis lead to a decreased electron flux and reduced ROS production, which falsely signifies hypoxia, resulting in normoxic HIF-1α activation. Both the HIF-1α activation and the related decrease in Kv1.5 expression are reversed by low doses of exogenous H2O2,, consistent with the redox theory for their etiology. A HIF-1α dominant-negative construct also restores Kv1.5 expression in FHR PASMC (51). Decreased Kv expression is an emerging hallmark of the PAH PASMC, occurring in human PAH (49,51) and all known experimental models (56–58). Interestingly, both Kv channels involved in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (Kv1.5 and Kv2.1) are inhibited by the anorexigens (59) and by 5-HT (60). In addition, endothelin-1 reversibly reduces the Kv1.5 currents (61). Restoring Kv1.5 expression reduces chronic hypoxic PH and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (62).

Mitochondrial therapy, eg, inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) by dichloroacetate (DCA) or Kv1.5 gene therapy, partially regresses both PAH and cancer (51,52,62), consistent with the concept that PAH and cancer share a mitochondrial basis. DCA restores oxidative metabolism in FHR PASMCs, shifting them away from the proliferative/apoptosis resistant glycolytic state. DCA also causes regression of PAH induced by chronic hypoxia or monocrotaline (51,56,57).

RhoA/ROCK-mediated Vasoconstriction

It is now clear that activation of RhoA/ROCK signaling is a major regulator of vascular tone (63). SMC tension is determined primarily by phosphorylation (contraction) and dephosphorylation (relaxation) of the regulatory myosin light chain (MLC), as described above. At a given level of cytosolic Ca2+, second messenger-mediated pathways can modulate the activity of MLCK and myosin light chain phosphatases (eg, MYPT1) to modify MLC phosphorylation and force, ie, to modify the Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction. Two major pathways in vascular smooth muscle are inhibition of MLCP action by ROCK-mediated phosphorylation of MYPT1, and protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and activation of the MLCP-inhibitor protein CPI-17.

Ca2+ desensitization is also a mechanism of vasodilation. Besides inducing SMC relaxation by desensitizing receptors and decreasing cytosolic [Ca2+] and MLCK activity, the NO/soluble guanylate cyclase/cGMP/PKG pathway also decreases Ca2+ sensitivity by phosphorylating and inactivating RhoA, or by directly phosphorylating MLCP, which increases MLCP activity (3). Similarly, vasodilation by stimuli that activate the adenylate kinase/cAMP/PKA pathway is also attributable partly to inhibition of RhoA/ROCK signaling (3).

RhoA/ROCK in acute pulmonary vasoconstriction

ROCK-mediated Ca2+ sensitization is necessary for the sustained phase of acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (64). Similarly, hypoxia directly activates RhoA in cultured PASMCs (65). Many studies have demonstrated the participation of ROCK in acute pulmonary vasoconstriction due to a variety of stimuli.

RhoA/ROCK in human PAH

Studies of RhoA/ROCK signaling in human PAH are limited. Low intravenous doses of fasudil acutely cause modest decreases in pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with PAH (66). Clinical trials examining the inhibition of RhoA/ROCK are under way.

Crosstalk Between Vascular Cells

Whether smooth muscle hyperplasia results from inherent characteristics of PASMCs or from dysregulation of molecular events that govern PASMC growth, such as signals originating from PAECs, remains an open question (67). In addition, there is evidence of crosstalk between adventitial cells and medial SMC.

Endothelial dysfunction in PAH may follow excessive release of paracrine factors that act either as growth factors to induce PASMC proliferation or as chemokines to recruit circulating inflammatory cells (44,68). Thus, exposure of PASMCs to culture medium from PAECs induces PASMC proliferation, and this effect is exaggerated when PAECs from patients with PAH are used (44).

The role of ECs in angiogenesis and remodeling is now better understood (69,70). In maturation, ECs no longer proliferate or migrate but promote vessel stabilization by recruiting periendothelial support cells, which differentiate into SMC-like cells (71). Failure of interactions between the two cell types, as seen in numerous genetic mouse models, results in severe and often lethal cardiovascular defects. Deficiencies in this process may lead to abnormal dilation of resistance pulmonary vessels, such as that seen in hereditary hemorrhagic telangectasia. Several studies suggest that the crosstalk between PAECs and PASMCs may be under the control of diverse pathways including the angiopoietin-1/Tie2, TGF-β/activin-receptorlike kinase (ALK) 1, and BMP/BMPR-II pathways (21,22,72). PAECs constitutively produce and release excessive amounts of soluble factors that act on PASMCs and inflammatory circulating cells to initiate or enhance pulmonary vascular remodeling and inflammation.

Cellular and Molecular Consequences of BMPR-II Mutation

Mutations in the BMPR2 gene have been found in approximately 70% of families with PAH (73,74). In addition, up to 25% of patients with apparently sporadic IPAH harbor mutations (75).

Normal BMP/TGF-β signaling

Bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) are the largest group of cytokines within the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily (76). BMPs are now known to regulate growth, differentiation, and apoptosis in a diverse number of cell lines (77). TGF-β superfamily type II receptors are constitutively active serine/threonine kinases. BMPR-II initiates intracellular signaling in response to specific ligands (78). Ligand specificity for different components of the receptor complex may have functional significance to the tissue-specific nature of BMP signaling (79,80). Recently, BMP9 was identified as a ligand that signals via a complex comprising BMPR-II and ALK-1(81). This important finding might provide a mechanism for the rare occurrence of severe PAH in some families with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia due to ALK-1 mutations (82). Following ligand binding, the type II receptor phosphorylates a glycine-serine rich domain on the proximal intracellular portion of an associated type I receptor (usually BMPR-IA [ALK-3] or BMPR-IB [ALK-6]). Activated type I receptors in turn phosphorylate cytoplasmic signaling proteins known as Smads, which are responsible for TGF-β superfamily signal transduction (83). BMPs signal via a restricted set of receptor-mediated Smads (R-Smads), Smads -1, -5, and -8, which must complex with the common partner Smad (Co-Smad), Smad-4, to translocate to the nucleus. Switching off Smad signaling in the cell is achieved via Smad ubiquitination and regulatory factors (Smurfs) (84) and by recently identified Smad phosphatases (85).

The consequences of BMPR2 mutation for BMP/TGF-β signaling

The mechanism by which BMPR-II mutants disrupt BMP/Smad signaling is heterogeneous and mutation specific (86). Of the missense mutations, substitution of cysteine residues within the ligand binding or kinase domain of BMPR-II leads to reduced trafficking of the mutant protein to the cell surface. At least for the ligand binding domain mutants, the mistrafficking can be rescued with chemical chaperones resulting in improvements in Smad signaling (87). In contrast, noncysteine mutations within the kinase domain reach the cell surface but fail to activate Smad-responsive luciferase reporter genes. Many mutations lead to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of the mutant transcript, leading to a state of haploinsufficiency. PASMCs from mice heterozygous for a null mutation in the BMPR2 gene are also deficient in Smad signaling (88,89). Thus haploinsufficiency or missense mutation leads to a loss of signaling via the Smad1/5 pathway in response to BMP2 and BMP4. However, marked siRNA knockdown of BMPR-II leads to increased Smad signaling in response to some ligands, for example BMP7 (80,89). This effect is mediated by increased signaling via the ActR-II receptor. In PASMCs, BMPR-II appears to mediate growth inhibition and differentiation, whereas ActR-II mediates osteoblastic differentiation (90).

Studies of BMP signaling cells and tissues from PAH patients

In the lung, BMPR-II is highly expressed on the vascular endothelium of the PAs (91) and at a lower level in PASMCs and fibroblasts. The expression of BMPR-II is markedly reduced in the pulmonary vasculature of patients with mutations in the BMPR-II gene (91). BMPR-II expression is also reduced in the pulmonary vasculature of patients with IPAH in whom no mutation in the BMPR2 gene was identified. A reduction in the expression of BMPR-II may be important to the pathogenesis of PAH, whether or not there is a mutation in the gene. In addition, since the level of BMPR-II expression in familial cases was considerably lower than predicted from the state of haploinsufficiency, this suggests that some additional environmental or genetic factor may be necessary to further reduce BMPR-II expression below a threshold that triggers vascular remodeling.

Phosphorylation of Smad1/5 is also reduced in the pulmonary arterial wall of patients with underlying BMPR-II mutations and in patients with IPAH with no identifiable mutation (92). The response of PASMCs to BMP ligands depends to some extent on the anatomical origin of cells. The serum-stimulated proliferation of cells harvested from the main or lobar PAs tends to be inhibited by TGF-β1 and BMPs 2, 4 and 7 (92). Indeed BMPs may induce apoptosis in these cells (93). The growth inhibitory effects of BMPs have been shown to be Smad1 dependent (92). In contrast, in PASMCs isolated from PAs of 1–2 mm diameter, BMPs 2 and 4 stimulate proliferation (92). This pro-proliferative effect of BMPs is dependent on the activation of ERK1/2 and p38MAPK. Both Smad and MAPK pathways are activated to a similar extent in cells from both locations, but the integration of these signals by the cell differs. This integration may be at the level of an important family of transcription factors, the inhibitors of DNA binding (Id genes) (94).

The response of vascular ECs to BMPs is dependent on the specific BMP ligand. Endothelial cells proliferate, migrate, and form tubular structures in response to BMP4 and BMP6 (95). In addition, BMPs in general protect endothelial cells from apoptosis (96). Interestingly, BMP9, which acts via BMPR-II and ALK-1, seems to inhibit PAEC proliferation. Knockdown of BMPR-II with siRNA increases the susceptibility of PAECs to apoptosis (96).

The contrasting effects of BMPs in pulmonary vascular ECs and the underlying PASMCs provide a hypothesis for pulmonary vascular damage and remodeling in familial PAH. A critical reduction in BMPR-II function in the endothelium may promote increased endothelial apoptosis, which compromises the endothelial barrier. This would allow ingress of serum factors and stimulate activation of vascular elastases. High rates of apoptosis in the endothelium could favor the development of apoptosis-resistant clones of ECs and lead to plexiform lesion formation. In the underlying media, PASMCs already compromised in their ability to respond to the growth-suppressive effects of BMPs are exposed to growth factors stimulating proliferation.

BMP signaling in rodent models of PAH

Reduced mRNA and protein expression of BMPR-II have been reported in the lungs of animals with experimental PH (97,98). In the monocrotaline rat model, adenoviral delivery of BMPR-II via the airways failed to prevent PH (99). However, targeted gene delivery of BMPR-II to the pulmonary endothelium did significantly reduce PH in chronically hypoxic rats (100).

Studies in knockout mice reveal the critical role of the BMP pathway in early embryogenesis and vascular development (101). However, heterozygous BMPR-II +/− mice survive to adulthood with no discernable phenotype (88). When heterozygotes are exposed to lung overexpression of interleukin (IL)-1β (102) or chronically infused with 5-HT (88), they develop more PH compared with wild type littermates. Thus, BMPR-II dysfunction increases the susceptibility to PH when exposed to other environmental stimuli. The relatively low penetrance of PAH within families supports a “two-hit” hypothesis, in which the vascular abnormalities are triggered by accumulation of genetic and/or environmental insults in a susceptible individual.

Transgenic mice overexpressing siRNA targeting BMPR-II exhibit about 10% of the normal levels of BMPR-II during development. These mice survive but do not develop spontaneous PAH. Intriguingly, they display a phenotype suggestive of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, with vascular ectasia and anemia (103). Conditional overexpression of a dominant negative kinase domain mutant BMPR-II in vascular SMCs of adult mice causes increased pulmonary vascular remodeling and PH (104). Conditional knockout of endothelial BMPR-II in adult mice has also been shown to predispose to PH (105).

The Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

The ECM not only represents a substrate for tissue morphogenesis, but also instructs almost all forms of cell behavior at the biophysical and biochemical levels through interactions with multiple receptors, including heterodimeric integrins composed of α and β subunits (106). Importantly, major qualitative and quantitative changes in the ECM underscore a number of human pathologies, including cancer and PAH. Functional differentiation of the breast epithelium relies upon contact with an appropriate basement membrane via β1 integrins that promote both proper cell polarity and patterns of gene expression (107). Similarly, the underlying ECM dictates whether human stem cells will differentiate into adipocytes or osteoblasts (108). In this instance, differentiation relies upon cytoskeletal tension generated by RhoA and ROCK. Many studies highlight the critical importance of understanding the reciprocal relationships between the ECM and signaling pathways, such as Rho GTPases. The connections between integrins, ECM ligands, and actin-based microfilaments inside the cell are indirect and are linked via scaffolding proteins, such as talin, paxillin and α-actinin (106). These scaffolds activate or recruit numerous signaling molecules, including focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src kinase family members, which then phosphorylate their substrates (109).

Tenascin-C in PAH

Tenascin-C (TN-C), a large ECM glycoprotein, is expressed within the medial SMC layer of injured and remodeling PAs from hypertensive animals (110) and humans (111,112). It surrounds proliferating PASMCs within arteries from hypertensive individuals (110,111). Furthermore, TN-C promotes PASMC proliferation and survival. For example, exogenous TN-C protein amplifies the SMC proliferative response to soluble growth factors, including epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor (110), by promoting clustering and activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, such as EGF receptors (113). Moreover, studies using isolated PASMCs and PAs from monocrotaline-exposed hypertensive rats revealed that suppression of TN-C using an antisense approach induces SMC apoptosis and regression of pulmonary vascular lesions (114).

Origins of the Myofibroblast in PAH

PH is characterized by cellular changes in the walls of PAs. Virtually all of these changes are characterized by increased numbers of cells expressing α-smooth muscle (SM)-actin (115). It has been thought that the SM-like cells that express α-SM-actin and accumulate in vascular lesions were derived from the expansion of resident vascular SMCs or adventitial fibroblasts. However, new data suggest other possible sources of α-SM-actin–expressing cells (SM-like cells and/or myofibroblasts) in various vascular diseases. Circulating progenitor cells can assume an SM-like phenotype (116). Resident vascular progenitor cells have also been demonstrated to express SM-like characteristics in several vascular injury states (117). Finally, the possibility that both epithelial and endothelial cells have the capability of transitioning into a mesenchymal or SM-like phenotype has been raised.

Endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EnMT)

The term endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EnMT), rather than transformation or transdifferentiation, relates to epithelial biology, where the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) has been more thoroughly investigated. EMT is a process in which epithelial cells lose cell-to-cell contacts and polarity and undergo dramatic remodeling of the cytoskeleton (118), with repression of epithelial markers. Concurrently, cells begin to express mesenchymal antigens, including FSP-1, α-SM-actin, fibronectin, and types I and III collagens, and manifest a proliferative and migratory phenotype. The transition of epithelial cells toward a mesenchymal phenotype occurs during embryonic development, and recent data suggest that EMT is important in cancer biology. A role for EMT during tissue injury leading to organ fibrosis is also becoming clear.

Less is known regarding EnMT than EMT. However, several groups have provided evidence that EnMT is critical in aortic and PA development (119). Endothelial cells labeled at an early stage of development appear later (at the onset of SMC differentiation) in the subendothelial space of the developing aorta and express α-SM-actin (120). Morphologic studies in human embryos suggest that endothelial-like cells may give rise to SMC during the maturation of both PAs and veins (121). Findings in experimental wound repair have suggested that EnMT may also take place in the adult. Similarly microvascular ECs transition into mesenchymal cells in response to chronic inflammatory stimuli (122). A role for EnMT in the neointimal thickening observed in transplant atherosclerosis and restenosis has also been suggested (120).

ECs from a variety of vascular beds retain the capability of transitioning into mesenchymal or even SM-like cells under several culture conditions (119). ECs derived from the adult bovine aorta convert to spindle-shaped α-SM-actin–expressing cells when treated with TGFβ-1(123). Human dermal microvascular ECs can be induced to transform into myofibroblasts in vitro, following long-term exposure to inflammatory cytokines (124). Recent studies have demonstrated that hypoxia is also capable of inducing transdifferentiation of PAECs into myofibroblast or SM-like cells in a process regulated by myocardin (125).

Circulating Mesenchymal Progenitor Cells in Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling

Bone marrow–derived circulating cells, known as fibrocytes, may be a source for myofibroblast accumulation during reparative processes in the lung (126). Fibrocytes are mesenchymal progenitors that coexpress hematopoietic stem cell antigens, markers of the monocyte lineage, and fibroblast products. They constitutively produce ECM components as well as ECM-modifying enzymes and can further differentiate into myofibroblasts. These cells can contribute to the new population of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that emerge at tissue sites during normal or aberrant wound healing, in ischemic or inflammatory fibrotic processes, and as part of the stromal reaction to tumor development (127).

The fibrocyte may differentiate into mature mesenchymal cells in vivo. Differentiation of fibrocytes into myofibroblastlike cells occurs where there is increased production of TGFβ-1 and/or endothelin. In these settings, fibrocytes or fibrocyte precursor cells demonstrate downregulation of leukocytic markers (eg, CD34 and CD45) with a concomitant upregulation of mesenchymal markers. A causal link between accumulation of fibrocytes at injured sites and ongoing tissue fibrogenesis or vascular remodeling has been provided in animal models of pulmonary disease (116). Inhibition of fibrocyte accumulation results in reduced collagen deposition and reduced accumulation of myofibroblasts. In the chronically hypoxic rat, monocyte/fibrocyte depletion markedly attenuated pulmonary vascular remodeling (116).

The transition of any cell type including ECs, progenitor cells, fibroblasts or even SMC into a myofibroblast becomes relevant to a better understanding of PH, as myofibroblasts can generate long-lasting constriction regulated at the level of Rho/Rho-kinase–mediated inhibition of MLC phosphatase (128). Thus, cells that have transitioned into fibroblastlike and myofibroblastlike cells may play a role in the inability of the vessel wall to dilate in response to traditional vasodilating stimuli.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ALK

activin-receptorlike kinase

- Ang-1

angiopoeitin-1

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- BMPR

bone morphogenetic protein receptor

- CCE

capacitative calcium entry

- DC A

dichloroacetate

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EMT

epithelial mesenchymal transition

- enMT

endothelial mesenchymal transition

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FHR

fawn-hooded rat

- GTP

guanosine triphosphatase

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- 5-HT

serotonin

- 5-HTT

serotonin transporter

- IPAH

idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension

- MLC

myosin light chain

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NO

nitric oxide

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PAI-1

plasminogen-activator inhibitor

- PGI2

prostacyclin

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PK

protein kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TN-C

tenascin-C

- Tph

tryptophan hydroxylase

- TRPC

canonical transient receptor potential

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Adnot has indicated no conflict of interest to disclose.

Dr. Archer has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Dupuis has served as a consultant for Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Encysive Technologies.

Dr. Jones has received an honorarium from Novartis.

Dr. MacLean has received funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the British Heart Foundation (BHF).

Dr. McMurtry has received a research grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Dr. Morrell has received a research grant from Novartis and has received honoraria for educational lectures from Actelion Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

Dr. Stenmark has indicated no conflict of interest to disclose.

Dr. Thistlethwaite has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Center for Medical Research and Education Fund (CMREF).

Dr. Weir has indicated no conflict of interest to disclose.

Dr. Weissmann received a research grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) “Excellence Cluster Cardio-Pulmonary System (ECCPS).”

Dr. Yuan has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rikitake Y, Liao JK. Rho GTPases, statins, and nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2005;97:1232–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196564.18314.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy KS. Signaling for contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle of the gut. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:345–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Csortos C, Kolosova I, Verin AD. Regulation of vascular endothelial cell barrier function and cytoskeleton structure by protein phosphatases of the PPP family. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L843–L854. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00120.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wojciak-Stothard B, Tsang LY, Paleolog E, Hall SM, Haworth SG. Rac1 and RhoA as regulators of endothelial phenotype and barrier function in hypoxia-induced neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1173–L1182. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00309.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masri FA, Xu W, Comhair SA, et al. Hyperproliferative apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L548–L554. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00428.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debidda M, Wang L, Zang H, Poli V, Zheng Y. A role of STAT3 in Rho GTPase-regulated cell migration and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17275–17285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagata K, Ishibashi T, Sakamoto T, et al. Rho/Rho-kinase is involved in the synthesis of tissue factor in human monocytes. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00750-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akbar H, Kim J, Funk K, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic evidence that Rac1 GTPase is involved in regulation of platelet secretion and aggregation. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1747–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takemoto M, Sun J, Hiroki J, Shimokawa H, Liao JK. Rho-kinase mediates hypoxia-induced downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 2002;106:57–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020682.73694.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W, Kaneko FT, Zheng S, et al. Increased arginase II and decreased NO synthesis in endothelial cells of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. FASEB J. 2004;18:1746–1748. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2317fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz S, Binion DG, Nelson VM, et al. Increased arginase activity and endothelial dysfunction in human inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1323–G1336. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00499.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pullamsetti S, Kiss L, Ghofrani HA, et al. Increased levels and reduced catabolism of asymmetric and symmetric dimethylarginines in pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 2005;19:1175–1177. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3223fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christman BW, McPherson CD, Newman JH, et al. An imbalance between the excretion of thromboxane and prostacyclin metabolites in pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:70–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207093270202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshikawa Y, Voelkel NF, Gesell TL, et al. Prostacyclin receptor-dependent modulation of pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:314–318. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2010150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geraci MW, Gao B, Shepherd DC, et al. Pulmonary prostacyclin synthase overexpression in transgenic mice protects against development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1509–1515. doi: 10.1172/JCI5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KT, Choi HH, Steinmetz MO, et al. Oligomerization and multimerization are critical for angiopoietin-1 to bind and phosphorylate Tie2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20126–20131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thistlethwaite PA, Lee SH, Du LL, et al. Human angiopoietin gene expression is a marker for severity of pulmonary hypertension in patients undergoing pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:65–73. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong AL, Haroon ZA, Werner S, Dewhirst MW, Greenberg CS, Peters KG. Tie2 expression and phosphorylation in angiogenic and quiescent adult tissues. Circ Res. 1997;81:567–574. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du L, Sullivan CC, Chu D, et al. Signaling molecules in nonfamilial pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:500–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan CC, Du L, Chu D, et al. Induction of pulmonary hypertension by an angiopoietin 1/TIE2/serotonin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12331–12336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933740100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewachter L, Adnot S, Fadel E, et al. Angiopoietin/Tie2 pathway influences smooth muscle hyperplasia in idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1025–1033. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-304OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu D, Sullivan CC, Du L, et al. A new animal model for pulmonary hypertension based on the overexpression of a single gene, angiopoietin-1. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01350-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kido M, Du L, Sullivan CC, Deutsch R, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA. Gene transfer of a TIE2 receptor antagonist prevents pulmonary hypertension in rodents. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao YD, Campbell AI, Robb M, Ng D, Stewart DJ. Protective role of angiopoietin-1 in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2003;92:984–991. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070587.79937.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hervé P, Launay JM, Scrobohaci ML, et al. Increased plasma serotonin in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Med. 1995;99:249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLean MR, Herve P, Eddahibi S, Adnot S. 5-hydroxytryptamine and the pulmonary circulation: receptors, transporters and relevance to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:161–168. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SL, Wang WW, Moore BJ, Fanburg BL. Dual effect of serotonin on growth of bovine pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in culture. Circ Res. 1991;68:1362–1368. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.5.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawrie A, Spiekerkoetter E, Martinez EC, et al. Interdependent serotonin transporter and receptor pathways regulate S100A4/Mts1, a gene associated with pulmonary vascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;97:227–235. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000176025.57706.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eddahibi S, Adnot S. Anorexigen-induced pulmonary hypertension and the serotonin (5-HT) hypothesis: lessons for the future in pathogenesis. Respir Res. 2002;3:9. doi: 10.1186/rr181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eddahibi S, Humbert M, Fadel E, et al. Serotonin transporter overexpression is responsible for pulmonary artery smooth muscle hyperplasia in primary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1141–1150. doi: 10.1172/JCI12805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eddahibi S, Hanoun N, Lanfumey L, et al. Attenuated hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice lacking the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1555–1562. doi: 10.1172/JCI8678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guignabert C, Raffestin B, Benferhat R, et al. Serotonin transporter inhibition prevents and reverses monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Circulation. 2005;111:2812–2819. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLean MR, Deuchar GA, Hicks MN, et al. Overexpression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene: effect on pulmonary hemodynamics and hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2004;109:2150–2155. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127375.56172.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guignabert C, Izikki M, Tu LI, et al. Transgenic mice overexpressing the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene in smooth muscle develop pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2006;98:1323–1330. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000222546.45372.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keegan A, Morecroft I, Smillie D, Hicks MN, MacLean MR. Contribution of the 5-HT1B receptor to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: converging evidence using 5-HT 1B-receptor knockout mice and the 5-HT 1B/1D-receptor antagonist GR127935. Circ Res. 2001;89:1231–1239. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frishman WH, Huberfeld S, Okin S, Wang YH, Kumar A, Shareef B. Serotonin and serotonin antagonism in cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular disease. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35:541–572. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb05013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Launay JM, Hervé P, Peoc'h K, et al. Function of the serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine 2B receptor in pulmonary hypertension. Nat Med. 2002;8:1129–1135. doi: 10.1038/nm764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callebert J, Esteve JM, Hervé P, et al. Evidence for a control of plasma serotonin levels by 5-hydroxytryptamine2B receptors in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:724–731. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanpain C, Le Poul E, Parma J, et al. Serotonin 5-HT2B receptor loss of function mutation in a patient with fenfluramine-associated primary pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morecroft I, Heeley RP, Prentice HM, Kirk A, MacLean MR. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors mediating contraction in human small muscular pulmonary arteries: importance of the 5-HT1B receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:730–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacLean MR, Sweeney G, Baird M, McCulloch KM, Houslay M. Morecroft I. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors mediating vasoconstriction in pulmonary arteries from control and pulmonary hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morecroft I, Loughlin L, Nilsen M, et al. Functional interactions between 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors and the serotonin transporter in pulmonary arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:539–548. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eddahibi S, Guignabert C, Barlier-Mur AM, et al. Cross talk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension: critical role for serotonin-induced smooth muscle hyperplasia. Circulation. 2006;113:1857–1864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morecroft I, Dempsie Y, Bader M, et al. Effect of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 deficiency on the development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:232–236. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252210.58849.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dempsie Y, Morecroft I, Welsh DJ, et al. Converging evidence in support of the serotonin hypothesis of dexfenfluramine-induced pulmonary hypertension with novel transgenic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:2928–2937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, et al. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H746–H755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu Y, Fantozzi I, Remillard CV, et al. Enhanced expression of transient receptor potential channels in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13861–13866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405908101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan JX, Aldinger AM, Juhaszova M, et al. Dysfunctional voltage-gated K+ channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1998;98:1400–1406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.14.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warburg O. Uber den Stoffwechsel der Tumoren. Berlin: Julius Springer; 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonnet S, Michelakis ED, Porter CJ, et al. An abnormal mitochondrial-hypoxia inducible factor-1α-Kv channel pathway disrupts oxygen sensing and triggers pulmonary arterial hypertension in fawn hooded rats: similarities to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113:2630–2641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonnet S, Archer SL, Allalunis-Turner J, et al. A mitochondria-K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McMurtry MS, Archer SL, Altieri DC, et al. Gene therapy targeting survivin selectively induces pulmonary vascular apoptosis and reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1479–1491. doi: 10.1172/JCI23203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Archer SL, Will JA, Weir EK. Redox status in the control of pulmonary vascular tone. Herz. 1986;11:127–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weir EK, López-Barneo J, Buckler KJ, Archer SL. Acute oxygen-sensing mechanisms. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2042–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McMurtry MS, Bonnet S, Wu X, et al. Dichloroacetate prevents and reverses pulmonary hypertension by inducing pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ Res. 2004;95:830–840. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145360.16770.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Michelakis ED, McMurtry MS, Wu XC, et al. Dichloroacetate, a metabolic modulator, prevents and reverses chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats: role of increased expression and activity of voltage-gated potassium channels. Circulation. 2002;105:244–250. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.101974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reeve HL, Michelakis E, Nelson DP, Weir EK, Archer SL. Alterations in a redox oxygen sensing mechanism in chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2249–2256. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weir EK, Reeve HL, Huang JM, et al. Anorexic agents aminorex, fenfluramine, and dexfenfluramine inhibit potassium current in rat pulmonary vascular smooth muscle and cause pulmonary vasoconstriction. Circulation. 1996;94:2216–2220. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.9.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cogolludo A, Moreno L, Lodi F, et al. Serotonin inhibits voltage-gated K+ currents in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: role of 5-HT 2A receptors, caveolin-1, and KV1.5 channel internalization. Circ Res. 2006;98:931–938. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000216858.04599.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Remillard CV, Tigno DD, Platoshyn O, et al. Function of Kv1.5 channels and genetic variations of KCNA5 in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1837–C1853. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00405.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pozeg ZI, Michelakis ED, McMurtry MS, et al. In vivo gene transfer of the O2-sensitive potassium channel Kv1.5 reduces pulmonary hypertension and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in chronically hypoxic rats. Circulation. 2003;107:2037–2044. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062688.76508.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ratz PH, Berg KM, Urban NH, Miner AS. Regulation of smooth muscle calcium sensitivity: KCl as a calcium-sensitizing stimulus. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C769–C783. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robertson TP, Hague D, Aaronson PI, Ward JP. Voltage-independent calcium entry in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction of intrapulmonary arteries of the rat. J Physiol. 2000;525:669–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Jin N, Ganguli S, Swartz DR, Li L, Rhoades RA. Rho-kinase activation is involved in hypoxia-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:628–635. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishikura K, Yamada N, Ito M, et al. Beneficial acute effects of rho-kinase inhibitor in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ J. 2006;70:174–178. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adnot S. Lessons learned from cancer may help in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1461–1463. doi: 10.1172/JCI25399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanchez O, Marcos E, Perros F, et al. Role of endothelium-derived CC chemokine ligand 2 in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1041–1047. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1559OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jain RK. Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9:685–693. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res. 2005;97:512–523. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Folkman J, D'Amore PA. Blood vessel formation: what is its molecular basis? Cell. 1996;87:1153–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eddahibi S, Chaouat A, Tu L, et al. Interleukin-6 gene polymorphism confers susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:475–476. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-038MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Machado RD, Aldred MA, James V, et al. Mutations of the TGF-β type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:121–132. doi: 10.1002/humu.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-β receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. The International PPH Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomson JR, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, et al. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-β family. J Med Genet. 2000;37:741–745. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miyazono K, Kusanagi K, Inoue H. Divergence and convergence of TGF-beta/BMP signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:265–276. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. BMP receptor signaling: transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rosenzweig BL, Imamura T, Okadome T, et al. Cloning and characterization of a human type II receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7632–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nickel J, Kotzsch A, Sebald W, Mueller TD. A single residue of GDF-5 defines binding specificity to BMP receptor IB. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Upton PD, Long L, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Functional characterization of bone morphogenetic protein binding sites and Smad1/5 activation in human vascular cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:539–552. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.David L, Mallet C, Mazerbourg S, Feige JJ, Bailly S. Identification of BMP9 and BMP10 as functional activators of the orphan activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1) in endothelial cells. Blood. 2007;109:1953–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trembath RC, Thomson JR, Machado RD, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of pulmonary hypertension in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:325–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Massagué J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi W, Chen H, Sun J, et al. Overexpression of Smurf1 negatively regulates mouse embryonic lung branching morphogenesis by specifically reducing Smad1 and Smad5 proteins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L293–L300. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00228.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen HB, Shen J, Ip YT, Xu L. Identification of phosphatases for Smad in the BMP/DPP pathway. Genes Dev. 2006;20:648–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rudarakanchana N, Flanagan JA, Chen H, et al. Functional analysis of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor mutations underlying primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1517–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sobolewski A, Rudarakanchana N, Upton PD, et al. Failure of bone morphogenetic protein receptor trafficking in pulmonary arterial hypertension: potential for rescue. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3180–3190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Long L, MacLean MR, Jeffery TK, et al. Serotonin increases susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in BMPR2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2006;98:818–827. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215809.47923.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu PB, Beppu H, Kawai N, Li E, Bloch KD. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptor deletion reveals BMP ligand-specific gain of signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24443–24450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu PB, Deng DY, Beppu H, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptor is required for BMP-mediated growth arrest and differentiation in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3877–3888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Atkinson C, Stewart S, Upton PD, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced pulmonary vascular expression of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor. Circulation. 2002;105:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012754.72951.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang X, Long L, Southwood M, et al. Dysfunctional Smad signaling contributes to abnormal smooth muscle cell proliferation in familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2005;96:1053–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000166926.54293.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang S, Fantozzi I, Tigno DD, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins induce apoptosis in human pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L740–L754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00284.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang J, Davies RJ, Southwood M, et al. Mutations in bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor cause dysregulation of Id gene expression in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells: implications for familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2008;102:1212–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Valdimarsdottir G, Goumans MJ, Rosendahl A, et al. Stimulation of Id1 expression by bone morphogenetic protein is sufficient and necessary for bone morphogenetic protein-induced activation of endothelial cells. Circulation. 2002;106:2263–2270. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033830.36431.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Kutryk MJ, Kuliszewski MA, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor-2 signaling promotes pulmonary arterial endothelial cell survival: implications for loss-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2006;98:209–217. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200180.01710.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rondelet B, Kerbaul F, Van Beneden R, et al. Signaling molecules in overcirculation-induced pulmonary hypertension in piglets: effects of sildenafil therapy. Circulation. 2004;110:2220–2225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143836.40431.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Takahashi H, Goto N, Kojima Y, et al. Downregulation of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L450–L458. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00206.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.McMurtry MS, Moudgil R, Hashimoto K, Bonnet S, Michelakis ED, Archer SL. Overexpression of human bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 does not ameliorate monocrotaline pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L872–L878. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00309.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reynolds AM, Xia W, Holmes MD, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein type 2 receptor gene therapy attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1182–L1192. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00020.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beppu H, Kawabata M, Hamamoto T, et al. BMP type II receptor is required for gastrulation and early development of mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 2000;221:249–258. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Song Y, Jones JE, Beppu H, Keaney JF, Jr, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. Increased susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Circulation. 2005;112:553–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu D, Wang J, Kinzel B, et al. Dosage-dependent requirement of BMP type II receptor for maintenance of vascular integrity. Blood. 2007;110:1502–1510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.West J, Fagan K, Steudel W, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative BMPRII gene in smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2004;94:1109–1114. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126047.82846.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hong KH, Lee YJ, Lee E, et al. Genetic ablation of the BMPR2 gene in pulmonary endothelium is sufficient to predispose to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;118:722–730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.736801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Boudreau NJ, Jones PL. Extracellular matrix and integrin signalling: the shape of things to come. Biochem J. 1999;339:481–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Streuli CH, Bissell MJ. Mammary epithelial cells, extracellular matrix, and gene expression. Cancer Treat Res. 1991;53:365–381. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3940-7_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miyamoto S, Katz BZ, Lafrenie RM, Yamada KM. Fibronectin and integrins in cell adhesion, signaling, and morphogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:119–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jones PL, Rabinovitch M. Tenascin-C is induced with progressive pulmonary vascular disease in rats and is functionally related to increased smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 1996;79:1131–1142. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jones PL, Cowan KN, Rabinovitch M. Tenascin-C, proliferation and subendothelial fibronectin in progressive pulmonary vascular disease. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1349–1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ihida-Stansbury K, McKean DM, Lane KB, et al. Tenascin-C is induced by mutated BMP type II receptors in familial forms of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L694–L702. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00119.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jones PL, Crack J, Rabinovitch M. Regulation of tenascin-C, a vascular smooth muscle cell survival factor that interacts with the αvβ3 integrin to promote epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and growth. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:279–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cowan KN, Jones PL, Rabinovitch M. Regression of hypertrophied rat pulmonary arteries in organ culture is associated with suppression of proteolytic activity, inhibition of tenascin-C, and smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ Res. 1999;84:1223–1233. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yi ES, Kim H, Ahn H, et al. Distribution of obstructive intimal lesions and their cellular phenotypes in chronic pulmonary hypertension: a morphometric and immunohistochemical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1577–1586. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Frid MG, Brunetti JA, Burke DL, et al. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling requires recruitment of circulating mesenchymal precursors of a monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:659–669. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stenmark KR, Davie N, Frid M, Gerasimovskaya E, Das M. Role of the adventitia in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Physiology (Bethesda ) 2006;21:134–145. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00053.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Radisky DC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4325–4326. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Arciniegas E, Neves CY, Carrillo LM, Zambrano EA, Ramirez R. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition occurs during embryonic pulmonary artery development. Endothelium. 2005;12:193–200. doi: 10.1080/10623320500227283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.DeRuiter MC, Poelmann RE, VanMunsteren JC, Mironov V, Markwald RR, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Embryonic endothelial cells transdifferentiate into mesenchymal cells expressing smooth muscle actins in vivo and in vitro. Circ Res. 1997;80:444–451. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hall SM, Hislop AA, Haworth SG. Origin, differentiation, and maturation of human pulmonary veins. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:333–340. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.3.4698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Romero LI, Zhang DN, Herron GS, Karasek MA. Interleukin-1 induces major phenotypic changes in human skin microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1997;173:84–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199710)173:1<84::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Arciniegas E, Sutton AB, Allen TD, Schor AM. Transforming growth factor beta 1 promotes the differentiation of endothelial cells into smooth muscle-like cells in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:521–529. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chaudhuri V, Zhou L, Karasek M. Inflammatory cytokines induce the transformation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells into myofibroblasts: a potential role in skin fibrogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:146–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhu P, Huang L, Ge X, Yan F, Wu R, Ao Q. Transdifferentiation of pulmonary arteriolar endothelial cells into smooth muscle-like cells regulated by myocardin involved in hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodelling. Int J Exp Pathol. 2006;87:463–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1807–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Strieter RM, Gomperts BN, Keane MP. The role of CXC chemokines in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:549–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI30562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tomasek JJ, Vaughan MB, Kropp BP, et al. Contraction of myofibroblasts in granulation tissue is dependent on Rho/Rho kinase/myosin light chain phosphatase activity. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:313–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]