Abstract

Schwann cells develop from multipotent neural crest cells and form myelin sheaths around axons that allow rapid transmission of action potentials. Neuregulin signaling through the ErbB receptor regulates Schwann cell development; however, the downstream pathways are not fully defined. We find that mice lacking calcineurin B1 in the neural crest have defects in Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Neuregulin addition to Schwann cell precursors initiates an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+, which activates calcineurin and the downstream transcription factors NFATc3 and c4. Purification of NFAT protein complexes shows that Sox10 is an NFAT nuclear partner and synergizes with NFATc4 to activate Krox20, which regulates genes necessary for myelination. Our studies demonstrate that calcineurin and NFAT are essential for neuregulin and ErbB signaling, neural crest diversification, and differentiation of Schwann cells.

Rapid transmission of action potentials in the vertebrate nervous system is achieved by insulating axons with myelin sheaths, the membrane outgrowth from Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system (1). Defects in myelination occur in many human diseases; however, the mechanisms regulating myelin formation are still not fully understood. Neuregulin-1 (NRG1) and its receptor tyrosine kinase, ErbB2/3 are required for Schwann cell development (2-7). Genetic studies implicate Sox10, Oct6 (SCIP or Tst1), Ets, Brn1 and 2, Krox20 (Egr2) and Nab1 and 2 in PNS myelination (8-12). The expression of Sox10 is maintained throughout Schwann cell development, whereas Oct6, Brn1/2, and Krox20 are induced later in immature and promyelinating Schwann cells after axonal contact (13-16). Krox20 is of particular interest because it coordinates the expression of several myelin structural proteins.

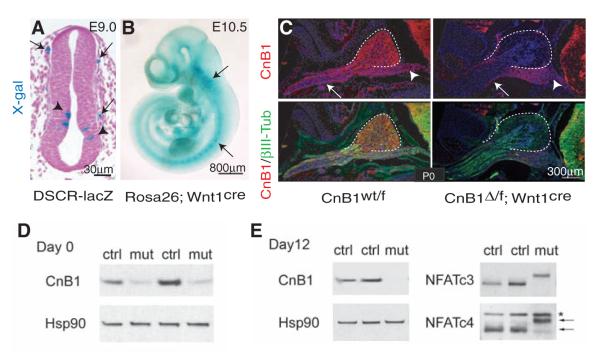

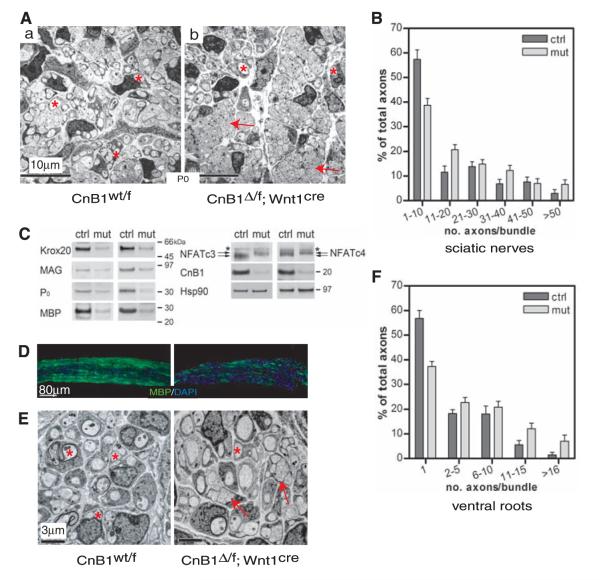

In many cell types, Ca2+ influx activates the phosphatase calcineurin, which dephosphorylates NFATc proteins, which in turn leads to their nuclear entry and assembly into NFAT transcription complexes (17-20). We observed that NFAT was active in migrating mouse neural crest cells at embryonic (E) day 9.0 (Fig. 1A) (21); therefore, we deleted CnB1, the essential regulatory subunit of calcineurin in neural crest, using Wnt1cre (22, 23) (Fig. 1B). By E11.5, CnB1 protein was almost undetectable in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and sympathetic ganglia (SG) (fig. S1A). The loss of CnB1 expression in DRG, SG, and Schwann cells persisted until death (within 20 hours after birth) (Fig. 1C and fig. S1, B and C). However, CnB1 was not deleted in axons of ventral roots derived from motor neurons where Wnt1cre is inactive (Fig. 1C). CnB1 was deleted in vitro in sensory neurons and Sox10-positive Schwann cell precursors (SCPs) (Fig. 1D and fig. S1D). NFATc3 and c4 were hyperphosphorylated, which indicated loss of calcineurin phosphatase activity (Fig. 1E). DRG architecture, cell proliferation, and cell death were not changed in the CnB1 mutant embryos (fig. S2A), and peripheral nerve projections were comparable to those of controls (fig. S2B). However, myelination of mutant sciatic nerves was defective, and fewer axons were sorted into a 1:1 ratio with Schwann cells (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S3, A and B). Mutant nerves also had a higher g ratio (axon diameter to total myelinated fiber diameter) (fig. S3C). They expressed less of the promyelinating protein Krox20, the early myelin protein MAG, and major compacted myelin components such as MBP and P0 (myelin basic protein and myelin protein zero, respectively) (Fig. 2, C and D). Furthermore, NFATc3 and c4 were hyperphosphorylated in mutant Schwann cells (Fig. 2C). These observations indicate that mice lacking CnB1 have defective myelination.

Fig. 1.

CnB1 is deleted in the PNS by Wnt1cre.(A) X-gal staining of E9.0 neural tube from a NFAT-reporter mouse line harboring LacZ under control of the DSCR1 enhancer region counterstained with nuclear fast red. Arrows, migrating neural crest cells; arrowheads, interneuron progenitors. (B) Whole-mountX-gal staining of E10.5 Rosa26; Wnt1cre mouse embryo. Arrows, sensory ganglia. (C) Immunostaining of newborn DRG and peripheral nerves at thoracic limb region by using CnB1-specific antibody. Arrows, CnB1-positive motor axons of peripheral nerves; arrowheads, ventral roots. (D and E) Immunoblots of CnB1 and NFATc3 and c4 from E13.5 DRG cocultures at day 0 (D) and day 12 (E). Heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a loading control. Arrows, NFATc4 proteins. *Cross-reactive protein.

Fig. 2.

Schwann cell differentiation is defective in CnB1 mutant mice. (A) Schwann cells in newborn mutant sciatic nerves fail to establish one-to-one relations with axons. Low-power electron microscopic images showing overall structure of sciatic nerves. Asterisks, sorted axons; arrows, unsorted axon bundles. (B and F) Quantification of axonal sorting (number of axons in bundles) of sciatic nerves and ventral motor roots of spinal cord (n = 4 per group; error bars, +SEM; P < 0.001; two-tailed t test). (C) Immunoblots of newborn sciatic nerves showing expression levels of myelin-specific proteins. Results from two different litters of animals are shown. Arrows, NFATc3 and c4 proteins. *Cross-reactive protein. Hsp90 is a loading control. (D) Immunostaining of cryosections of newborn sciatic nerves using MBP-specific antibody (green). (E) Electron microscopic images of ventral motor roots. Asterisks, sorted axons; arrows, unsorted axon bundles. All experiments were performed with at least four littermate pairs of mice.

Investigation of the Schwann cell lineage revealed that SCPs were found in both control and mutant peripheral nerves at E11.5 (fig. S4A). At E13.5, control and mutant DRG contained similar numbers of sensory neurons and SCPs (fig. S4B). Unlike neuregulin or erbB mutant mice (2, 5), SCPs from CnB1 mutant embryos showed no differences in proliferation or apoptosis in vitro in response to NRG1 stimulation (fig. S4, C and D). We observed comparable numbers of proliferating Schwann cells in control and mutant newborn sciatic nerves (fig. S5A).

Survival of SCPs has been shown to be dependent on trophic support from sensory neurons (24). To rule out the possibility that hypomyelination was due to dysfunction of mutant sensory neurons, we cocultured mutant SCPs with control sensory neurons under conditions that supported sensory neuron survival. Fewer MBP-positive Schwann cells were found in mutant SCP cocultures, although comparable numbers of sensory neurons were present in both control and mutant cocultures (fig. S5, B to D). ErbB2 and 3 expression and phosphorylation levels were normal in mutant SCPs, and sensory neurons expressed comparable amounts of pro-NRG1 and the cleaved form of NRG1 (NTF), which suggested that BACE1, an enzyme involved in NRG1 processing, functioned normally in mutant sensory neurons (fig. S5E).

To investigate cell autonomy of the myelination defects, we took advantage of selective deletion of CnB1 in Schwann cells, but not in motor neurons of CnB1Δ/f; Wnt1cre mice and found that axonal sorting was reduced in mutant ventral roots and phrenic nerves (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S6A). This was similar to the defect seen in dorsal roots from CnB1Δ/f; Wnt1cre mutants, where CnB1 is deleted in both sensory neurons and Schwann cells (fig. S6B). In a second approach, we examined CnB1f/f; Nestincre mice, where CnB1 is deleted in sensory neurons, but not in Schwann cells (fig. S7, A and B). CnB1 deletion did not affect the numbers of MBP-positive Schwann cells or axonal sorting (fig. S7, C to F). These two lines of evidence indicate that the myelination defects in CnB1 mutant mice are due to a Schwann cell—autonomous mechanism.

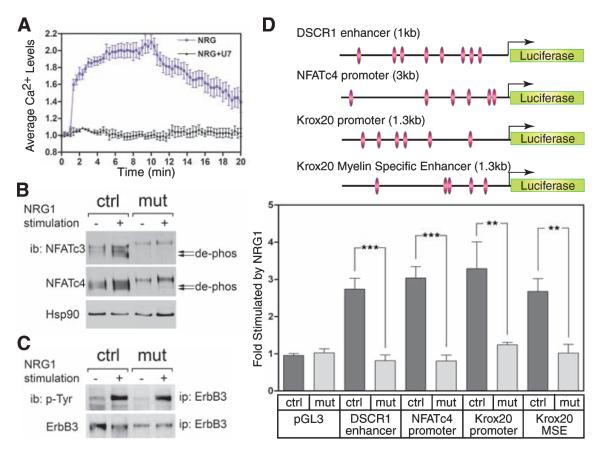

In our analysis of signaling pathways that activated calcineurin/NFAT in DRG cocultures, we found that NRG1 induced phospholipase C—γ (PLC-γ)—dependent Ca2+ influx in SCPs (Fig. 3A) and CnB1-dependent dephosphorylation of NFATc3 and c4 (Fig. 3B). NRG1 also stimulated Ca2+ influx in sensory neurons (fig. S8A). CnB1 deletion had no effect on NRG1-induced phosphorylation of the ErbB3 receptor, which indicated that calcineurin functions downstream of ErbB (Fig. 3C). ErbB kinase inhibitors specifically blocked NRG1-stimulated NFATc3 and c4 dephosphorylation, whereas neither phosphati-dylinositol 3-kinase nor mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitors had an inhibitory effect (fig. S8, B and C).

Fig. 3.

Calcineurin/NFAT is required for NRG1 and ErbB signaling. (A) Ca2+ influx stimulated by NRG1. DRG cocultures were preloaded with the Ca2+ sensor Fura-2AM in the presence or absence of PLC-γ inhibitor U73122, 30 min before stimulation. Ca2+ influx was detected, and average Ca2+ levels were measured. (B) Dephosphorylation of NFATc3 and c4 is not induced in mutant cocultures after NRG1 stimulation, as examined by immunoblotting (ib). Arrows, dephosphorylated (active) NFATc3 and c4. (C) Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of ErbB3 following the activation by NRG1. ErbB3 were isolated by immunoprecipitation (ip). Tyrosine phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting using phosphotyrosine-specific antibody. The blot was reprobed with ErbB3-specific antibody to verify protein expression levels. (D) Calcineurin/NFAT-dependent transcription is stimulated by NRG1. E13.5 DRG cocultures were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing the DSCR1 enhancer, NFATc4 promoter, Krox20 promoter, or Krox20 MSE. Luciferase activities were measured after 20 hours of NRG1 stimulation. Fold activation is relative to unstimulated cells (n = 6; error bars, +SEM; **P < 0.01; ***P <0.001; t test).

NRG1 not only induced changes in NFATc phosphorylation, but also activated NFAT-dependent transcription, measured with two NFAT reporters (25, 26) (Fig. 3D). NRG1-stimulated reporter activity was not detected in mutant cocultures, which indicated that calcineurin functions downstream of ErbB and upstream of NFAT. The observation that Krox20 expression was reduced in CnB1 mutant Schwann cells led us to examine the role of NFAT in Krox20 regulation. We found that both the promoter and the myelin-specific enhancer (MSE, +35 kilobases) (27) required calcineurin for their activity (Fig. 3D). Three NFATc consensus sites were present in the MSE that bound NFAT complexes (fig. S9, A and B). Because Krox20 is expressed selectively in Schwann cells, but not in DRG neurons (16), these results provide a third line of evidence that calcineurin/NFAT functions in Schwann cells to directly promote myelination.

The specificity of NFAT complexes on target genes arises from assembly of NFATc family members with nuclear partner proteins (18-20). To identify nuclear partners, we purified NFAT complexes from E11.5 mouse neural tubes (as sufficient quantities of SCPs were not available) using oligonucleotide affinity columns. Mass spectrometry analysis identified the B group of the Sox family proteins (Sox1, 2, 3, 14, and 21) (fig. S10, A and B). Because Sox10 has a similar binding sequence and is expressed throughout Schwann cell development (10), we tested whether Sox10 interacts with NFATc using a Schwann cell line expressing NFATc4 and Sox10. Sox10 copurified with NFATc4 using control but not mutant oligonucleotides containing the NFATc-binding sites of the DSCR1 (Down syndrome critical region 1) enhancer or Krox20 MSE (NRE4-s) (figs. S10C and S13). Because these oligonucleotides do not contain Sox10-binding sites, the isolation of Sox10 by control, but not mutant, oligonucleotides supports the direct interaction of NFATc4 and Sox10. Protein domain deletion studies indicated that Sox10 bound to the Rel homology domain of NFATc4 (fig. S10D).

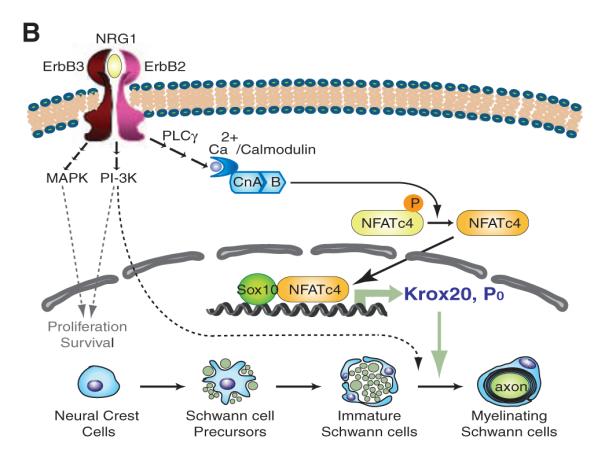

Because several conserved NFATc-binding sites lie next to putative Sox10-binding sites in the Krox20 MSE (fig. S9A), we tested coactivation of the Krox20 MSE by NFATc4 and Sox10 (Fig. 4A). NFATc4 and Sox10 synergistically activated Krox20 MSE-driven luciferase expression in DRG cocultures. Brn2 and Oct6 are also important regulators of Krox20 transcription (28). The functional interaction between calcineurin/NFAT and Sox10 might provide NRG1 responsiveness to the Krox20 MSE and might assist Brn2 and Oct6 in its regulation.

Fig. 4.

Synergistic effects of NFATc4 and Sox10 on myelin gene expression. (A) NFATc4 and Sox10 synergistically activate the Krox20 MSE and P0 promoter. DRG cocultures were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing the Krox20 MSE, P0 promoter or Krox20 promoter. Expression constructs encoding constitutively active calcineurin A (CnA*), NFATc4, and Sox family members were co-transfected. Luciferase activities were measured. Fold activation is relative to reporter baseline activities (n = 6, error bars, +SEM, ***P < 0.001; t test). (B) Model of myelination process regulated by calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway. Solid arrows, calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway; dotted arrows, pathways defined by previous literature.

Synergy between NFATc4 and Sox10 was also observed with the P0 promoter (Fig. 4A and fig. S11) but not with the Krox20 or NFATc4 promoters (Fig. 4A and fig. S12B). Sox10 and Krox20 have been shown to regulate the P0 intron1 (29). We found that calcineurin/NFAT also stimulated the P0 intron1 (fig. S12). Thus, calcineurin/NFAT signaling likely regulates P0 expression directly through the P0 promoter by cooperating with Sox10 and indirectly through stimulating intron1 activity by inducing Krox20 expression. Sox2 blocked transcriptional activation (Fig. 4A), consistent with the observation that it is an inhibitor of Schwann cell differentiation (30). Using oligonucleotide affinity purification, we found that NFATc4 facilitated Sox10 binding to the NRE4 region of Krox20 MSE (NRE4-L), because mutation of the NFATc-binding sequence led to reduced cobinding of Sox10 (fig. S13). Together, these data indicate cooperation between NFATc4 and Sox10 in myelin gene expression.

Our data indicate that calcineurin/NFAT signaling regulates the development of Schwann cells at two steps (Fig. 4B). One is by acting downstream of neuregulin and ErbB to directly activate Krox20 at the promyelination stage, which in turn activates later myelin genes. Another is by activating genes encoding myelin structural proteins, such as P0, at the myelination stage. NFATc4 interacts with Sox10 and provides specificity to the calcineurin/NFAT pathway for the Schwann cell lineage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. A. Borres for insightful comments; K. J. Liu, Q. Lin, and J. Perrino for technical assistance; and J. I. Wu for critically reading this manuscript. G.R.C is an Investigator of HHMI. These studies were supported by grants from NIH (NS046789, HD55391, and AI60037) to G.R.C.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/323/5914/651/DC1 Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S13 References

References and Notes

- 1.Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:671. doi: 10.1038/nrn1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Nature. 1995;378:386. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong Z, et al. Neuron. 1995;15:585. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nave KA, Salzer JL. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006;16:492. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woldeyesus MT, et al. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2538. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurel P, Salzer JL. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04635.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahmatullah M, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:6245. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britsch S, et al. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paratore C, Goerich DE, Suter U, Wegner M, Sommer L. Development. 2001;128:3949. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCauley DW, Bronner-Fraser M. Nature. 2006;441:750. doi: 10.1038/nature04691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson DB, Langner K, Namini SS, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002;20:154. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan R, et al. BMC Mol. Biol. 2007;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedrich RP, Schlierf B, Tamm ER, Bosl MR, Wegner M. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:1821. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1821-1829.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaegle M, et al. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.258203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaegle M, et al. Science. 1996;273:507. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topilko P, et al. Nature. 1994;371:796. doi: 10.1038/371796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw JP, et al. Science. 1988;241:202. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flanagan WM, Corthesy B, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR. Nature. 1991;352:803. doi: 10.1038/352803a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, Peisley A, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:251. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain J, McCaffrey PG, Valge-Archer VE, Rao A. Nature. 1992;356:801. doi: 10.1038/356801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 22.Neilson JR, Winslow MM, Hur EM, Crabtree GR. Immunity. 2004;20:255. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:1323. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessen KR, et al. Neuron. 1994;12:509. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arron JR, et al. Nature. 2006;441:595. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu H, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703622200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghislain J, et al. Development. 2002;129:155. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghislain J, Charnay P. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:52. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeBlanc SE, Jang SW, Ward RM, Wrabetz L, Svaren J. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le N, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:2596. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.