I. Introduction

A. Coverage of This Review

This review describes design principles which chemists have applied to the construction of DNA analogues for use in the recognition of specific DNA and RNA sequences. The focus is primarily on molecular strategies which are aimed at increasing binding affinity and specificity, the benchmarks of successful molecular recognition. The field of oligonucleotide chemistry has grown explosively in the last 10 years. For that reason this review is not intended to comprehensively cover the entire field of oligonucleotide chemistry, but will instead focus on this more narrow topic. The reader is invited to visit other recently published reviews for surveys of oligonucleotide synthesis1,2 and of oligonucleotide conjugates, 3 and for in-depth coverage of antisense or antigene therapeutic strategies.4–7

B. Applications of Modified Nucleic Acids

The development of solid-phase, automated methods for the synthesis of DNA8 and RNA9 has in the last 10 years led to widespread use of nucleic acids and their modified analogues in chemistry, biology, and medicine. While synthesized DNA strands having the natural structure are undeniably and widely useful as primers, linkers, and probes in molecular biological techniques, there is a host of possible modified DNA structures with many new properties and applications which exist as future possibilities in the chemist’s mind.

A number of possible applications of modified DNAs have come to the forefront as factors driving this field of study. Oligonucleotides are widely useful in research, as tools for biochemistry and molecular biology. Second, oligonucleotides are now being used both commercially and experimentally in molecular diagnostic strategies for identifying disease-related genes and pathogens.10 Finally, oligonucleotides and analogues are being vigorously pursued as therapeutic agents targeted to human disease.4–7 Most if not all of these applications rely on the ability of these DNAs or analogues to form specific helical complexes, either folded intramolecularly or binding intermolecularly to a target nucleic acid. It is this specific noncovalent recognition that is the focus of this monograph.

Modification of the basic nucleic acid structure (Figure 1) can enhance properties which already are present in DNA, or modifications can bestow new properties which natural DNA and RNA do not have. Such new properties can be extremely useful for the practical application of nucleic acids to biotechnology, biochemistry, biology, and medicine. Some desirable properties, such as resistance to degradation in cells or good pharmacokinetic behavior, are important primarily for biomedical applications, and are left for discussion elsewhere.4–7 Here I will discuss specifically the physical recognition properties of DNA and RNA, and how they can be altered or improved.

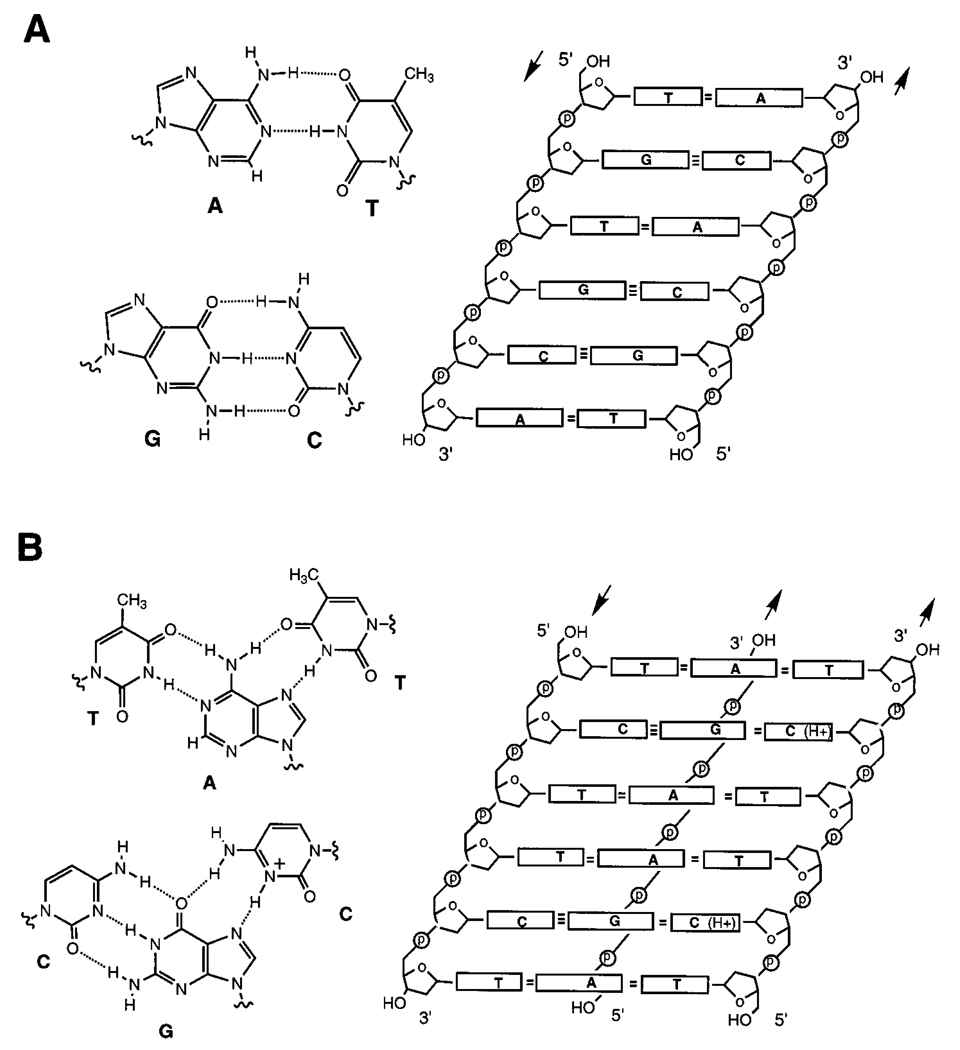

Figure 1.

The structures of duplex (A) and triplex (B) DNAs. On the right are unwound representations of the helices showing strand orientation (arrows), and on the left, cross sections showing base pairing interactions. The triplex depicted is the pyr•pur-pyr type; note, however, that the third (Hoogsteen) strand in a triplex can also be oriented in the opposite direction with different base orientations (not shown).

C. Preorganization and DNA

The term “preorganization” was first brought forth by Cram in the analysis and design of small organic guest–host complexes.11 It was recognized that entropy disfavors the formation of such complexes for two reasons: first, three degrees of translational and rotational entropy are lost in forming a complex from two separate molecules, and second, if either of the separate molecules has free internal bond rotations, then the “freezing out” of all such rotations on forming the complex is also entropically unfavorable. 12 Although the first effect is for the most part an unavoidable aspect of molecular recognition, the second can be addressed by the chemist. If a host molecule or ligand is constructed so as to be rigidly held in the binding conformation prior to complexation, then little or no entropy cost due to fixing bond rotations will be necessary in binding.11 Thus a flexible molecule can be preorganized in the synthesis for optimum binding. (Note that it is crucial that this preorganization does not hold the molecule rigidly in the wrong conformation!).

DNA is an ideal candidate for preorganization (Figure 1 and Figure 2). A single-stranded nucleic acid is quite flexible, with about five freely rotating bonds per phosphate. Helix formation is therefore highly unfavorable entropically and is a spontaneous reaction only because a very favorable enthalpy term just compensates (see below).

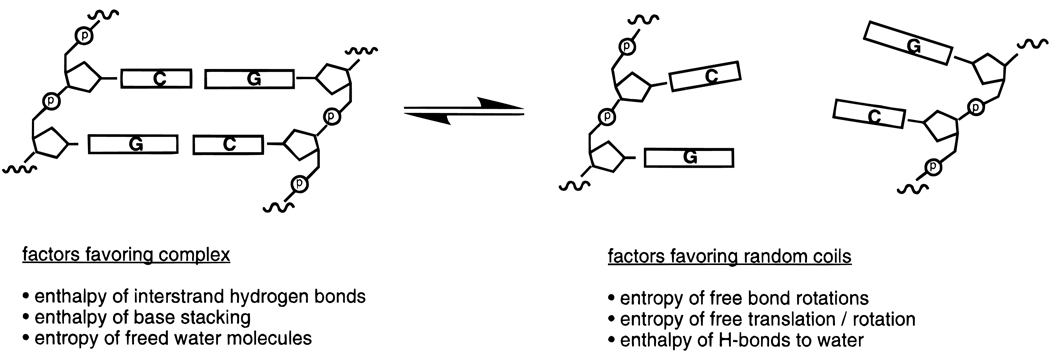

Figure 2.

Illustration of some of the thermodynamic factors associated with helix formation in DNA. Overall, enthalpy is highly favorable for helix formation but entropy is nearly as highly unfavorable. The two-state model is shown, in which strands undergo an all-or-none transition between helical and single-stranded states; however, this is an oversimplification for many nucleic acid complexes.

II. Basic Design Principles

A. Noncovalent Interactions Which Stabilize DNA and RNA

All nucleic acid helices are stabilized by base stacking and/or hydrogen bonding interactions. A single-stranded nucleic acid can form a stable single-stranded helix without any base pairing partners if its nucleotide bases are proficient at stacking. Double, triple- and quadruple-stranded helices (which can be formed either intra- or intermolecularly) are stabilized both by base stacking and by hydrogen bonding.

1. Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding can be considered chiefly an electrostatic interaction between an acidic proton and a good electron donor.13 Since recognition of natural DNA and RNA usually requires complementary hydrogen-bonding groups, perhaps the only way to increase the strength of the H-bonding interactions in DNA/RNA recognition is to increase the acidity of the H-bond donors or the basicity of the acceptors. This is not an easy task, given the strict structural requirements for a correctly paired aromatic nucleotide base and its geometry in the helix. If altered base-pairing arrangements are permitted, then there is somewhat more structural flexibility for altering hydrogen-bond strength.14,15

Hydrogen bonding is only one of the two most important interactions which stabilize double-helical structure (Figure 3). The second is the stacking of adjacent bases (which is likely to be of similar importance). 16 Altering the hydrogen-bonding strength in general affects mainly the final helical complex and not as much the single-stranded state, and so does not fall under the concept of preorganization. However, altering base stacking can effect the single-stranded state as much as the final helical complex and so can be a useful strategy in preorganization.

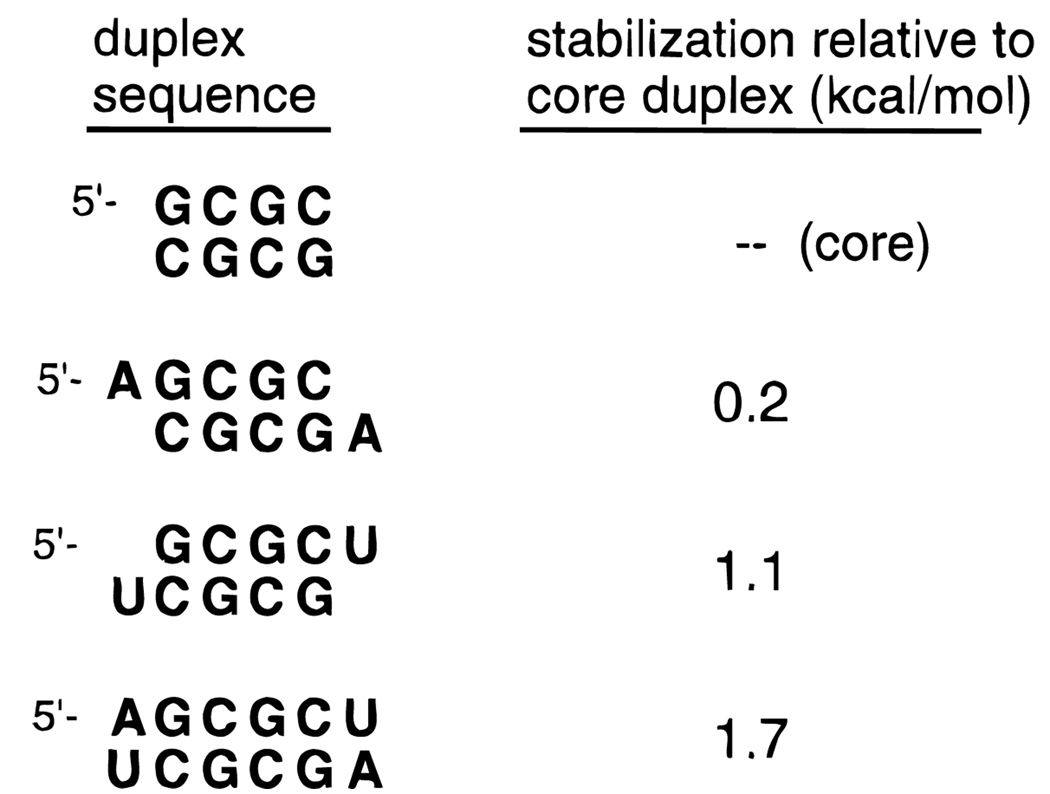

Figure 3.

Data from “dangling end” experiments help point out the contributions of base stacking and base pairing to nucleic acid double helices. For example, the sequence GCGCU forms a self-complementary duplex with U dangling off the 3′ end. This dangling U adds 1.1 kcal/mol of stability to the core duplex, and this is a measure of the stacking ability of U. Data are taken from ref 17.

2. Base Stacking

It has been recognized for some time that base stacking is as crucial to stabilization of DNA and RNA helices as hydrogen bonding is. One experimental measure of stacking in RNA indicated that stacking and H bonding each contribute ~1 kcal/mol per base pair to the total stability (Figure 3).16,17 Aromatic π–π stacking occurs largely between bases within one strand of the helix, although because of the helical twist there is also a contribution of stacking between bases in opposite strands of a duplex. Strengthening intrastrand base stacking could in principle serve to preorganize a single strand for binding a target strand. This, however, raises the important question: what specific interactions contribute to base stacking, and how might these be enhanced?

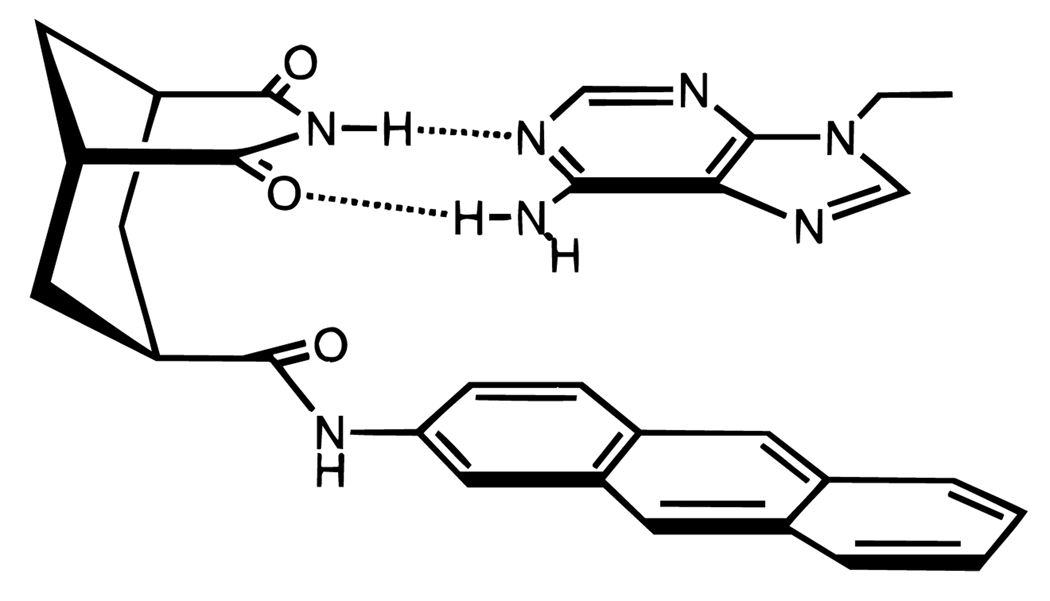

Although quite a number of theoretical analyses of base stacking have been carried out,18–22 very few experimental studies of stacking in nucleic acids exist. A number of small-molecule model studies in aqueous solution have attempted to experimentally address this problem.23–25 Studies of the natural bases in short RNA helices showed that the bicyclic purines (A and G) stack more strongly than do pyrimidines (C and U).16 In smaller molecules, stacking of simple aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives on adenine has been measured (Figure 4), and the results indicated that the surface area of overlap is an important factor.24 Several factors, including dispersion forces, dipole–induced dipole attractions,25 solvophobic effects,26 and electrostatics all may play a role in base stacking, and only recently has the relative importance of these factors begun to be experimentally examined in duplex DNA26 (see below). In one short DNA duplex, the stacking free energies of thymine and adenine were measured at −0.6 and −1.0 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 1).26

Figure 4.

Example of a small-molecule model for aromatic π–π stacking in water.24 The binding of the adenine analog is measured as a function of varied aromatic groups in the host (anthracene is shown here). Binding free energy correlates reasonably well with surface area of the molecule.

Table 1.

Comparison of Stacking Affinities of Natural DNA Bases and Simple Aromatic Analogs, As Measured by Dangling End Studies in a Self-Complementary DNA Duplex (Sequence d(XCGCGCG)2a

| dangling moiety | Tm (°C)b | −ΔG°37 (kcal/mol)c |

ΔΔG° stacking |

|---|---|---|---|

| (none) | 41.0 | 8.1 ± 0.2 | – |

| thymine (13) | 48.1 | 9.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| adenine (15) | 51.6 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| benzene (17) | 48.3 | 9.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| naphthalene (18) | 56.2 | 10.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| phenanthrene (19) | 57.3 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| pyrene (20) | 64.1 | 11.4 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

Stacking parameters (ΔTm, ΔΔG°) are obtained by subtracting data for the core hexamer duplex from that for duplexes with dangling bases added at the (X) position. 26

Conditions: 1 M NaCl, 10 mM Na•phosphate pH 7.0, 5.0 µM DNA strand concentration.

Values obtained by plotting 1/Tm vs ln (CT) with data from at least five concentrations.

3. Electrostatic Effects

Aside from hydrogen bonding, by far the most important electrostatic factor in DNA helix formation is the repulsion of negative charge on phosphate between strands forming a double (or higher) helix. This is largely an enthalpic effect which becomes a destabilizing factor in the final complex (depending, of course, on ionic strength).27 A number of molecular strategies for lowering this repulsion in DNA have been realized in recent years; for example, an oligonucleotide could be modified to carry an uncharged28,29 or even a positively charged backbone,30,31 thus leading to lowered or eliminated electrostatic repulsion or even attraction between the oligonucleotide and its target. While not an entropic preorganization strategy, it can be useful for enhancing binding, especially at low ionic strength. At physiological ionic strength, however, preorganization strategies can yield very high affinities even retaining the normal phosphate charge (see below).

B. On the Thermodynamics and Kinetics of DNA and RNA Helix Formation

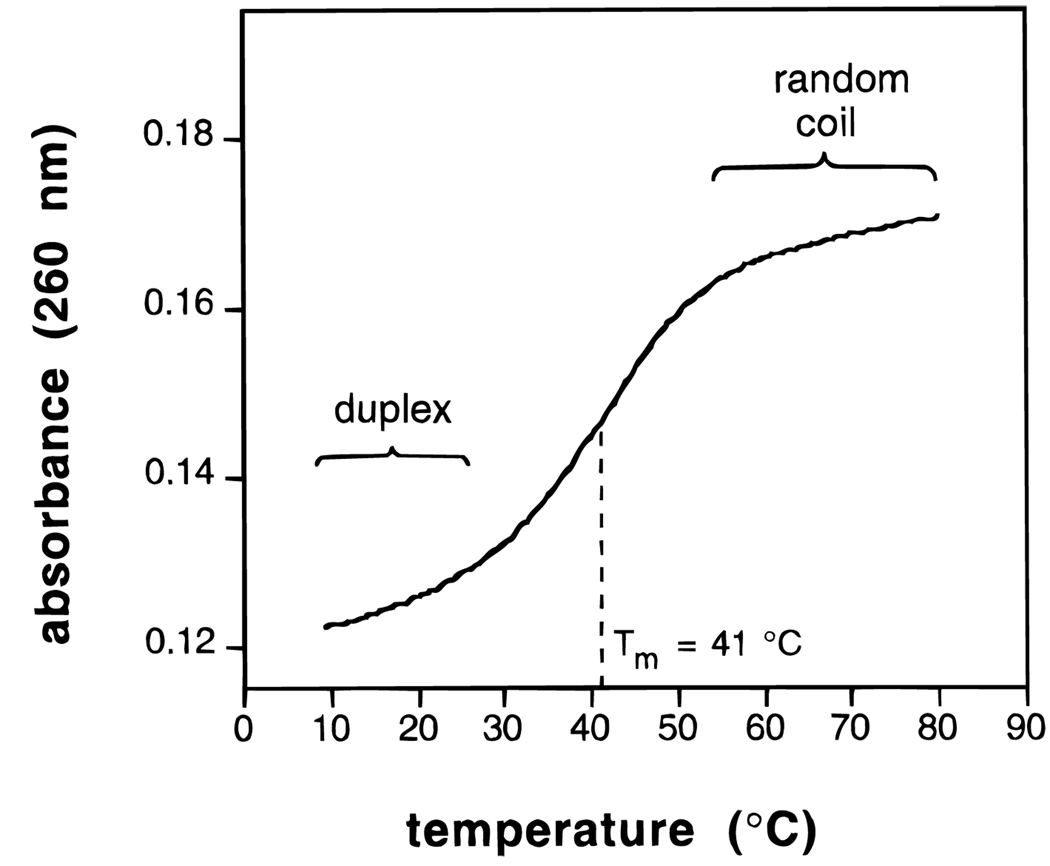

The most common method for measurement of the thermodynamics of nucleic acid helix formation is the thermal denaturation experiment, which is carried out in a UV cell in a thermostated UV–vis spectrophotometer. The nucleic acid is placed in the aqueous buffer of interest, and the temperature is slowly raised (say, from 10 to 100 °C) while absorbance is monitored (usually at 260 nm) (Figure 5). Melting of the helix coincides with an increase in the absorbance of the DNA bases as they become unstacked. Analysis of the curve shape and measurement of changes in the curve as a function of concentration can give measures of enthalpy and entropy for helix formation, if the helix follows simple two-state (all-or-none) behavior.32 It should be noted, however, that many nucleic acid complexes are not well described by a two-state model; a useful thermodynamic method which does not require two-state behavior is calorimetry.33 Kinetics of association and dissociation can be observed by a number of methods including stopped-flow rapid mixing techniques,34 analysis of hysteresis in melting/annealing curves,35 and by following surface plasmon resonance effects.36

Figure 5.

Example of an experimental thermal denaturation curve for a DNA complex in aqueous buffer. The UV absorbance is followed as temperature is raised slowly from low to high temperature. The curve shown is that for the duplex formed by dCGCGCG in water with 1 M NaCl, pH 7.0 (10 mM phosphate) with 5 µM DNA.26

It is important to recall that a data point such as free energy for a complex represents the position of an equilibrium between random coil (unbound) and helical (complex) forms (Figure 2). This equilibrium can be altered (stabilizing the complex) either by changes which affect the stability of the complex, or just as easily by changes which affect the stability of the unbound oligonucleotide. This latter approach lies at the heart of the preorganization concept.

1. Entropy and Enthalpy Contributions

As mentioned above, nearly all nucleic acid complexation (duplexes, triplexes, and tetraplexes) is highly favorable in the enthalpic term and highly unfavorable in the entropic term, as judged by experimental values determined in aqueous buffers.37 For example, the sequence 5′-dCGCGCG forms a self-complementary duplex with a free energy (37 °C) of −8.1 kcal/mol.26,38 The measured ΔH°, however, is −46 kcal/mol, and the entropic term (−TΔS°) at that temperature is +38 kcal/mol.26 Thus, the enthalpy and entropy terms are large and opposing, and are much larger than the sum free energy stabilizing the duplex. This actually makes some sense if one considers the interactions involved.39 The formation of many hydrogen bonds and π–π stacked contacts might be expected to be favorable enthalpy terms. The fixing of many bond rotations would be expected to be unfavorable entropically. Thus we say that DNA helix formation is enthalpy driven, while protein folding (often dominated by classical hydrophobic interactions) is more commonly entropy driven.

2. Interpretation of Experimental Values

This kind of molecular interpretation of enthalpic and entropic effects in nucleic acid helices is not quite that simple, however. First, there is the solvent and counterions in solution to consider. In the single-stranded form, DNA is well-solvated, forming strong H bonds to many water molecules, and some of these bonds are lost when the DNA–DNA H bonds are formed. In addition, the ionic interactions between cations and the single strand are likely to be different than those with the duplex. Those many interactions all carry enthalpy and entropy terms of their own. The second problem in interpretation of these experimental quantities is that enthalpy and entropy are interrelated when considering covalent and noncovalent molecular conformation.12,39,40 For example, when a base becomes increasingly stacked with a neighbor, this may make the enthalpy more favorable but the entropy less favorable (as bond rotations are limited). For all these reasons it is therefore difficult, and perhaps hazardous, to overly interpret measured enthalpy and entropy effects in molecular recognition, particularly in a complex case like nucleic acids where the enthalpy and entropy terms are so large relative to the free energy of the helix.

3. Kinetics of Helix Formation

The kinetics of nucleic acid helix formation are markedly regular. Experimental values and methods have been reviewed recently,17 and so I will mention here only a short summary of the findings. Short strands of DNA or RNA (say, less than ~ 100 nucleotides) form duplexes, whether they are fully complementary or not, at roughly the same rate. The second-order rate constant for binding is commonly 106–107 M−1 s−1. Since duplexes vary greatly in stability, this means that dissociation rates vary greatly depending on size, sequence, conditions, and complementarity. One exception to the common association rates mentioned above is triple-helix formation: when a third strand binds to a preformed duplex, the association rate for triplex formation can be considerably slower; rate constants have been reported in the range 2–4 orders of magnitude slower than duplex formation (with some dependence on pH and ionic strength).34,35,41,36 Cooperative triple helices, however, can be formed on single-stranded targets at the same rapid rate as duplexes.34 A recent report also found that purine-rich third strands can form triplexes qualitatively faster than do pyrimidine strands.42

C. Desirable Properties in Recognition: Affinity and Sequence Selectivity

The yardsticks of successful molecular design for recognition have long been binding affinity and binding selectivity. Many, but not all, applications of modified oligonucleotides would benefit from increased affinity. Almost all applications would also benefit from higher selectivity; in DNA and RNA, selectivity usually means the ability to discriminate among closely related target sequences.

1. When Is High Affinity Desirable?

Tight binding is desirable in oligonucleotide complexes when the end result requires only noncovalent complexation and not some subsequent activity which requires dissociation. A high affinity often means slow dissociation from the target and therefore a long lifetime for detection or for inhibition of biological processes.43 It also implies being able to bind even when present at very low concentrations. Thus, a high affinity is desirable in many if not most of our current applications. However, tight binding is not desirable in some situations.44 For example, if an analogue has raised affinity but not elevated sequence specificity, it may bind to undesired targets and have an unintended effect there. In addition, hybridization is sometimes linked to a catalytic event which requires turnover; for example, ribozyme RNAs bind to an RNA substrate, induce cleavage, and then they must dissociate to find a new target. If binding is too tight, then dissociation is slow and thus limits the effectiveness of ribozyme catalysis.44

2. The Hazards of Increasing Affinity Noncooperatively

Several approaches to increasing the affinity of binding by an oligonucleotide do not simultaneously increase selectivity. Such analogues may have undesired nonspecific effects in some applications. A few examples are worth noting: DNA intercalators are small aromatic molecules which generally bind DNA quite nonselectively at almost any sequence. Tethering an intercalator loosely to an oligonucleotide can very significantly increase overall binding affinity,45 as the affinity of the intercalator is added to that of the DNA. However, the intercalator will bind along with the oligonucleotide whether or not the oligonucleotide is bound at a correct site (and will even bind when the oligonucleotide is not bound at all). Thus the intercalator may increase affinity about equally for matched and mismatched targets.46

Another example of increasing affinity without increasing selectivity is exemplified by oligonucleotide analogues which carry positive charge.30,31 As mentioned above, such compounds can bind quite tightly to complementary strands, especially at low ionic strength because of the lowered negative charge repulsion between strands. However, all else being equal, the positive charge is likely to raise the affinity for binding all nucleic acids, since all carry more or less the same regularly spaced negative charges.

3. Affinity and Selectivity Are Not Mutually Exclusive

One of the central points of this review is that high affinity and high selectivity can be achieved from a single structural modification. The concept of preorganization can be used to design a modification which rigidifies the ligand (oligonucleotide) prior to binding so that it more resembles the bound conformation. This achieves the entropic benefit stated above, because fewer bond rotations are frozen during complexation, and thus affinity is higher. At the same time, the molecule is organized into a shape which is more complementary to the desired target than to undesired ones. This increases selectivity because mismatched targets will cause unfavorable responses such as nonoptimum bond angles or steric clashes. Some examples of molecules with increased affinity and selectivity are given below.

D. Cooperativity, Rigidity, and Molecular Design

In a large molecule with many binding domains, such as a nucleic acid oligomer, this rigidity is discussed in terms of cooperativity. This is a measure of the communication of interactions between different binding domains. For example, how much does disruption of one DNA base pair affect the energy of the one next to it, or the one five base pairs away? For perfect preorganization, a molecule must be perfectly rigid, and disruption of one base pair then affects all the others equally. Although a DNA double helix does have a good deal of cooperativity, it is far from perfectly rigid, and this is especially true in the single-stranded state. This means that there is a good deal of room for improvement of recognition properties.

III. Strategies for Enhancing Base Stacking

Since the majority of the base-stacking interaction in nucleic acids is between bases within a strand, the strengthening of stacking will have the tendency to cause the single-stranded oligonucleotide to become preorganized into a more regular helical conformation. This will therefore favor complexation by lowering the entropic cost. This section will focus on specific chemical strategies for increasing stacking.

A. Addition of Simple Substituents to DNA Bases

It has been recognized for some time that C-5 methylated pyrimidines are more stabilizing to nucleic acid helices than when the methyl is absent. Early studies with polymeric strands indicated an advantage in thermal stability with this substitution, 47,48 and more recent studies with short, well-defined sequences have confirmed a thermodynamic advantage as well.49–51 One study found that the addition of each methyl group to uracil either in RNA or in DNA adds 0.1–0.5 kcal/mol of stability to double- and triple-helical structure.51 It is thought that this effect is due to increased polarizability of methylated bases, which enhances van der Waals interactions with neighboring bases.52 Other C-5 subtituents such as bromine and chlorine are also nearly as stabilizing (Figure 6).50 One exception to this rule is the recent finding that addition of C-5 methyls on cytidines is destabilizing in all-RNA (but not DNA) triple helices.53

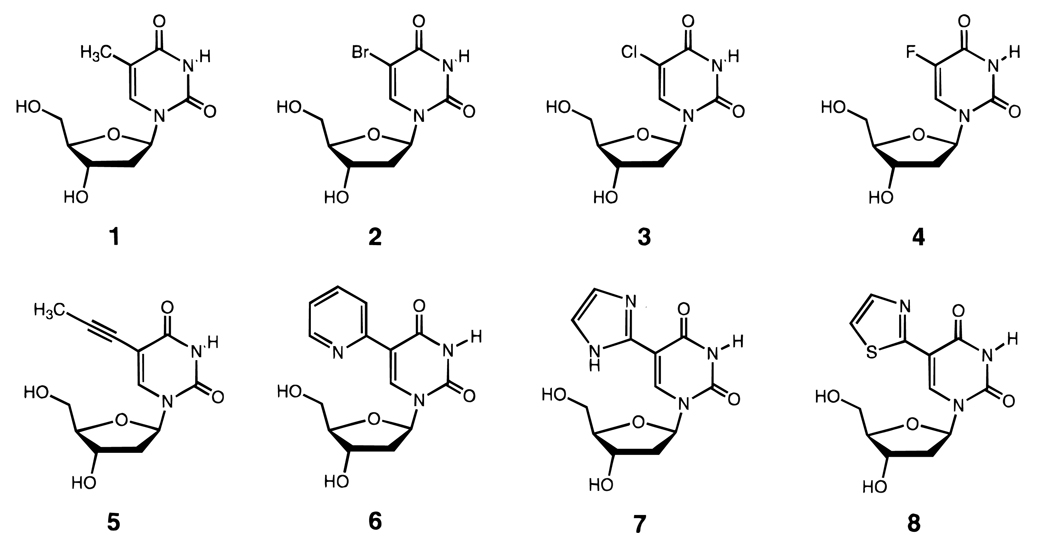

Figure 6.

Structures of C-5-modified uridine nucleosides (2–8) which stabilize nucleic acid helices, probably by enhancing base stacking.50–59 All the substituents shown are stabilizing relative to deoxyuridine (which has hydrogen at the C-5 position), including the C-5 methyl group of thymidine (1).

Also in this vein is the finding that pyrimidine C-5 propyne groups are also stabilizing to double (and in some cases, triple) helices,54,55 although some exceptions are known.56 For example, addition of propyne to dU thermally stabilizes duplexes with RNA (in one report) by 1.7 °C per substitution and triplexes by 2.4 °C (Figure 6). A propyne group would also tend to enhance polarizability and hydrophobic surface area and thus enhance base stacking.57 Lower C-5 alkyne groups up to hexyne are stabilizing, although alkane substituents longer than methyl are destabilizing. 55

It is more difficult to find a site for similar substitution in purines. Replacement of the N-7 nitrogen with carbon (i.e., N-7 deazapurines) gives a position which can be substituted with methyl, bromine, or chlorine groups for additional helix stabilization.58 Again, it seems likely that this is due to enhanced stacking, although this has not been investigated in detail as yet.

B. Increasing Surface Area of DNA Bases

Since surface area of overlap in a stacking interaction may be correlated with strength of the interaction, investigators have recently begun to find ways to increase the surface area of DNA bases without disrupting their ability to form the necessary hydrogen bonds. Matteuci et al. have reported that addition of aromatic hetercyclic groups to the C-5 position of pyrimidines significantly stabilizes helices, again, possibly by enhancing stacking (Figure 6). A thiazole substituent has shown the most promise of these cases.59

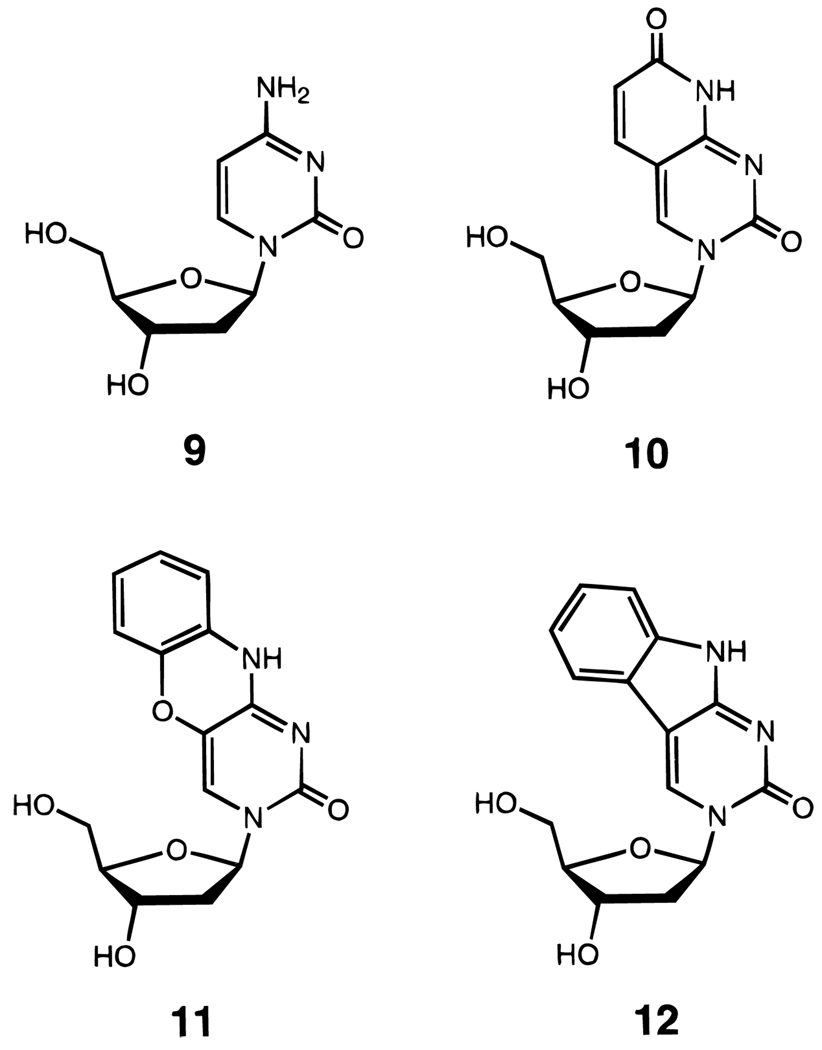

Also in this vein are studies in which extra rings are added to pyrimidines (Figure 7).60,61 Bicyclic and tricyclic cytidine analogues have been reported recently; one tricyclic analogue has been reported to increase Tm by as much as 5.0 °C per substitution,61 although thermodynamics have not yet been measured for sequences containing this analogue.

Figure 7.

Structures of deoxycytidine (9) and some modified deoxycytidine nucleosides which have increased surface area by addition of extra rings (10–12). These compounds thermally stabilize DNA helices relative to deoxycytidine.60,61

C. Use of Nonpolar DNA Base Analogues

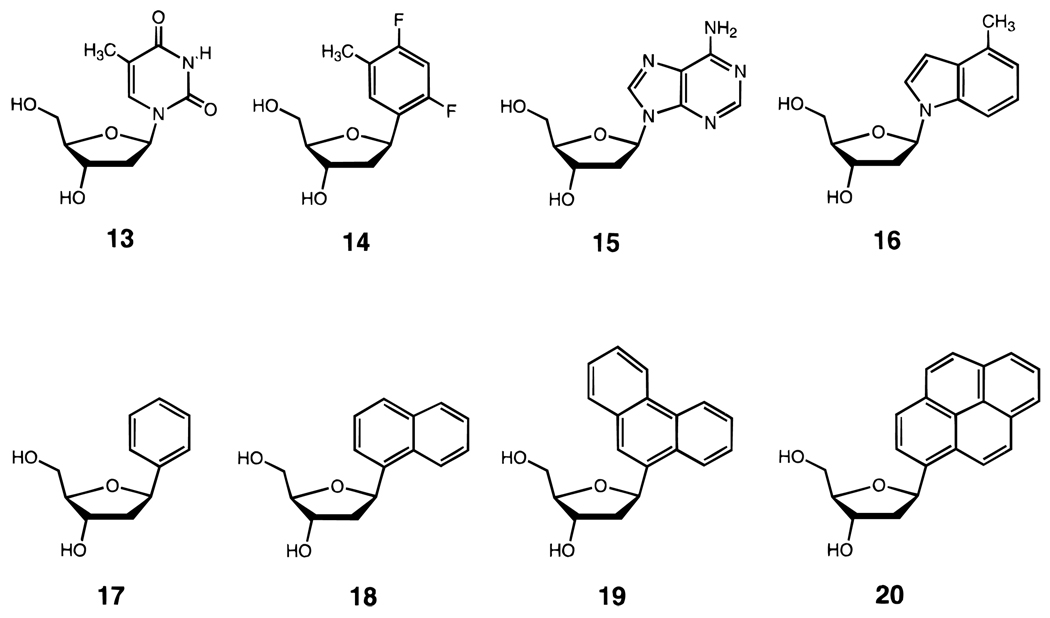

The above strategies are useful for substitution within a helix-forming sequence. Recently it has been shown that helices can be stabilized significantly by the addition of strongly stacking bases at the end of the helix, even when the bases in question do not undergo pairing.37,62 A recent study of the thermodynamic stacking affinities of natural DNA bases and simple aromatic hydrocarbons (Figure 8) showed that hydrophobicity, in addition to surface area, is an important factor in enhancing stacking. A pyrene-derived nucleoside analogue was shown to add 1.7 kcal/mol of stability and 11.5 °C in Tm per each substitution in a DNA helix (Table 1).26 Examination of entropic and enthalpic factors supported the hypothesis that stacking preorganizes the single-stranded helix prior to complexation.63 Such nonpolar DNA base analogues have also been shown to stabilize intramolecular hairpin-type helices.62

Figure 8.

Structures of nucleosides with aromatic hydrocarbons as DNA base analogues. Compounds 14 and 16 are nonpolar isosteres of natural thymidine (13) and deoxyadenosine (15) respectively. C-nucleosides 17–20 have simple aromatic hydrocarbons replacing the bases. Compounds 14, 16, and 18–20 all stack more strongly than the natural DNA bases.26,37,62

IV. Strategies for Limiting Bond Rotations

The above strategy relies on noncovalent bonds to preorganize helical structure. In this section are described approaches to the use of covalent bonds to limit bond rotations prior to complexation.

A. Backbones with Restricted Freedom

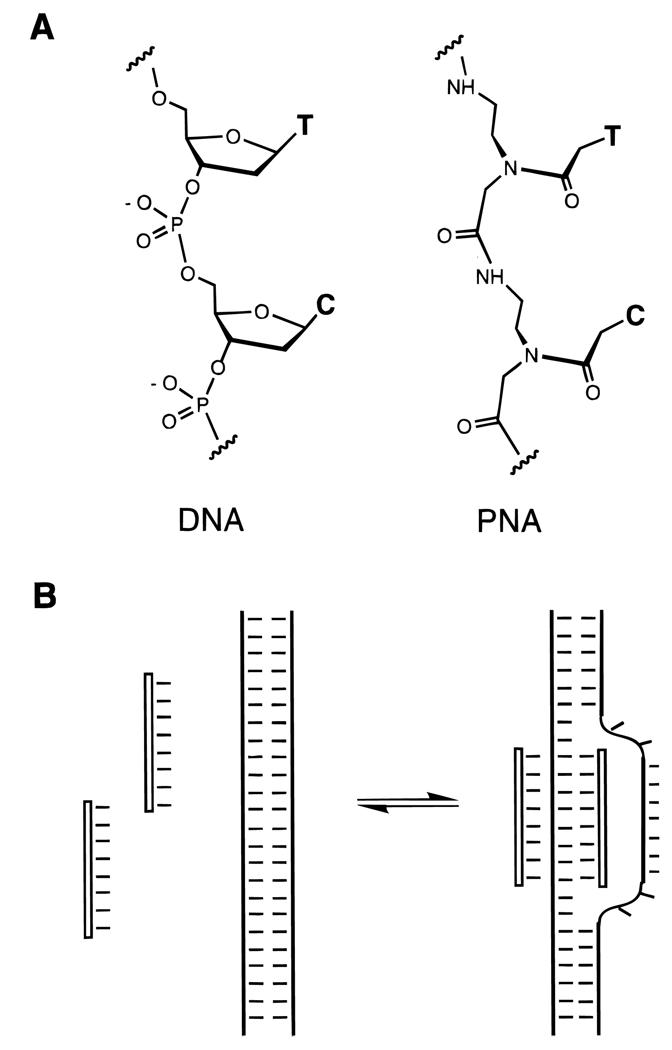

One approach to the limiting the bond rotations in the phosphodiester backbone of DNA or RNA is to replace this backbone with bonds that are less free to rotate. There are five single bonds which connect two adjacent pentose rings in nucleic acids, and many five-bond replacements have been reported. Most of these are uncharged replacements; a few of these have shown some success in increasing affinity, especially at lower ionic strength. Some of the more successful examples of such a replacement are connections which contain an amide bond (Figure 9), since an amide has restricted rotation about the carbonyl–nitrogen bond. Two such cases merit mention in this respect; the first is the peptide nucleic acid (PNA) analogue (Figure 17),29,64 which forms strong duplexes with DNA at lowered ionic strength, and which forms very strong triplexes even at normal ionic strength. The second is an amide linkage which can also stabilize helical complexes.65 It is likely that both these analogues benefit from the restricted rotation of the backbone.

Figure 9.

Examples of DNA analogues with amide bonds replacing phosphodiester bonds, in comparison to natural DNA (left). The amide linkage has restricted rotational freedom relative to the natural phosphodiester linkage. See ref 65.

Figure 17.

(A) Structure of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) next to natural DNA (left) and (B) illustration of the binding of duplex DNA by two PNA strands at low ionic strength, forming a “D-looped” structure. One strand (at a homopurine site) is bound in a triplex with two identical PNA strands, and the unbound strand is displaced from the double helix.29,64

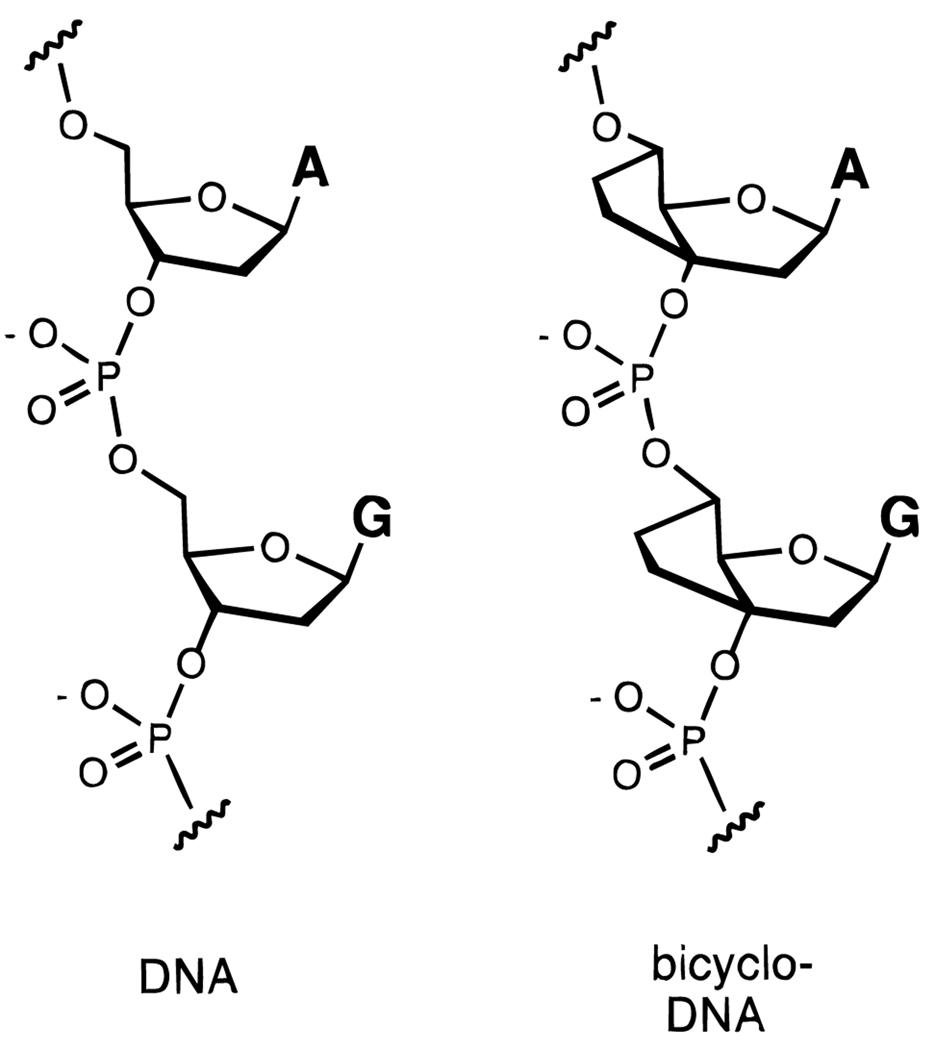

B. Bicyclo-DNA

Another strategy for preorganizing DNA might be to rigidify the normally flexible furanose ring by chemical modification. Leumann et al. have done this by addition of an ethylene bridge from C-3′ to C-5′, adding a second five-membered ring to the natural structure (Figure 10).66–68 This oligonucleotide analogue has been termed “bicyclo-DNA”, and oligonucleotides designed to form both duplexes and triplexes have been studied. This analogue has been found in some cases to hybridize strongly with an RNA strand; for example, a strand of bicyclo-DNA with adenine bases binds poly(U) more tightly than does a similar strand of natural adenine-containing DNA,67 and similar effects have been observed in triplex formation.68 Some sequences of bicyclo-DNA bind a single-stranded or duplex complement with lower affinity than natural DNA; in part this may be due to the adoption of an unfavorable ring conformation.66–68

Figure 10.

Structure of “bicyclo-DNA” (right) in comparison to natural DNA (left). Addition of a second fused ring to the furanose ring confers added conformational rigidity.66–68

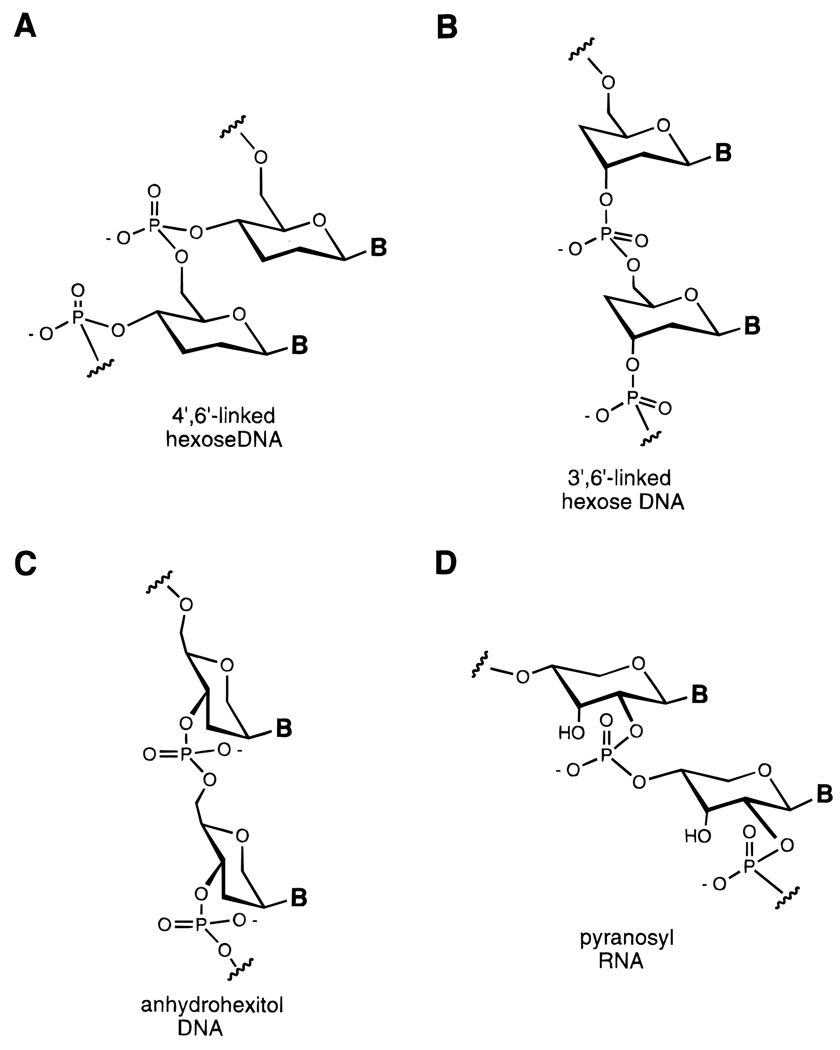

C. Hexose-DNAs and RNAs

It has long been recognized that five-membered rings are considerably more flexible than six-membered rings. Furanose sugars have a low barrier to interconversion of ring conformers, while pyranoses are generally much more stabilized in a chair conformation. In recent years the groups of Eschenmoser and Herdewijn and Van Aerschot have synthesized several analogues of DNA and RNA in which the furanose ring is expanded to a six-membered ring (Figure 11).69–73 In some cases this has led to oligonucleotide analogues which hybridize more strongly to DNA and to RNA than the natural furanose-based structures do.

Figure 11.

DNA and RNA analogues with hexose sugars (and related structures) replacing ribose or deoxyribose.69–73 Six-membered rings confer conformational rigidity because of their preference for the chair conformation.

One fascinating example of this concept is the pyranosyl-RNA analogue (pRNA) of Eschenmoser.70 This structure contains the same number of carbons as RNA but with six-membered rings rather than five-membered ones, and with one fewer freely rotating internucleotide bond (Figure 11D). Hybridization studies have shown that oligonucleotides constructed with this backbone bind to RNA complementary strands very strongly; this result is attributed in large part to the conformational rigidity of the modified sugar–phosphate backbone. Also intriguing is the recent finding that strands of pRNA carrying a cyclic phosphate group at one end can undergo autoligation with another strand bound at an adjacent site.71

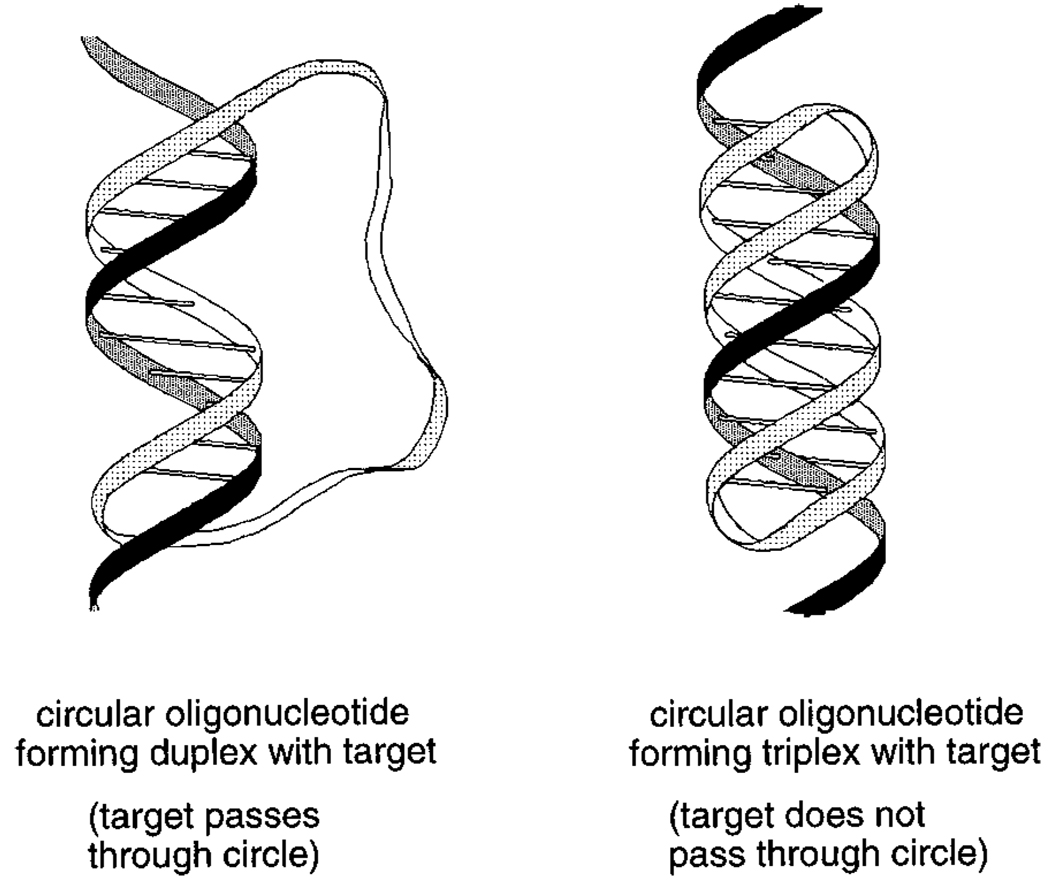

D. Circular DNAs and RNAs

One way to very significantly limit the conformational freedom of a flexible chain is to cyclize the chain. One early example of this concept in short duplex DNAs was the addition of loops closing the ends to give dumbbell-like structures.74–76 More recently there has been considerable interest in circular DNAs which lack this internally complementary structure (thus allowing them to bind other nucleic acids). Synthesis of cyclic DNAs and RNAs has been studied in many laboratories,77–81 and recently a number of strategies for binding such cyclic molecules to nucleic acid targets have been described.82–86 A circular oligonucleotide can bind a single-stranded target strand of RNA or DNA by forming standard Watson–Crick bonds. However, such binding is limited because of the helical twist of DNA: the strand being bound will therefore required to pass through the circle once per ~ 10–12 bases of hybridization (corresponding to a turn of the helix, Figure 12).83,85,86 This is an unlikely event except when binding very short target strands. One approach to successful binding of longer target sequences which has shown much more success is triplex formation with the target strand (see below).

Figure 12.

The binding of a circular oligonucleotide to a single-stranded RNA or DNA target: (left) Watson–Crick binding alone, showing how helix formation tends to bring the target strand through the circle, and (right) combined Watson–Crick and Hoogsteen binding, which results in no such topological linkage.85

V. Linking Binding Domains

The linking of two binding domains for complexation of a large molecular target is another well-tested and successful strategy for preorganization. This has the effect of combining all the noncovalent bonds into a single binding event. This is favorable enthalpically because of the addition of new binding interactions and is entropically favorable (relative to separate binding domains) because less entropy of translation and rotation is lost on binding. One aspect of critical importance in such a strategy is the design of the linking group or groups. For best preorganization (and thus highest affinity and selectivity), a linker should be both rigid and orient the binding domains in the productive geometry.

A. Noncovalent Links

Noncovalent links between binding domains have the advantage of simplifying synthesis and requiring smaller molecules; however, they have the possible disadvantage of being relatively weak, which can limit the potential for ideal preorganization and cooperativity. True preorganization requires that the two binding domains can and do dimerize by their noncovalent interaction even in the absence of the target. Dimerization which requires the target for assistance will tend to be a lower-affinity interaction, although selectivity can be high because a mismatch near the site of the interactions will disrupt the binding of both domains.

1. Dimerization for Triplex Binding

Two oligonucleotides can hybridize simultaneously to directly adjacent sites in a single-stranded or double-stranded target. This binding brings the ends in a position to stack directly on each other in coaxial fashion, which is a weak interaction but does bring some cooperativity to the total binding. For example, the adjacent binding of two oligonucleotides to duplex DNA was found to be stabilized by 1.8 kcal/mol,87 and if C-5 propynyl groups are present on the stacking interface, this can rise to > 4 kcal/mol.88 Some noncovalent dimerizations having greater cooperativity are known. For example, Dervan and co-workers have shown that two oligonucleotides can form a dimeric triple-helical complex with duplex DNA by forming a Watson–Crick stemlike interaction (Figure 13).89 In a related approach, a short Watson–Crick stem can aid in dimerization of two triplex-forming strands, and a drug (echinomycin, for example) can bind the stem and enhance cooperativity. 90

Figure 13.

Dimerization of two oligonucleotides for cooperative triplex formation at two sites separated by two base pairs in duplex DNA.88,89

B. Covalent Links

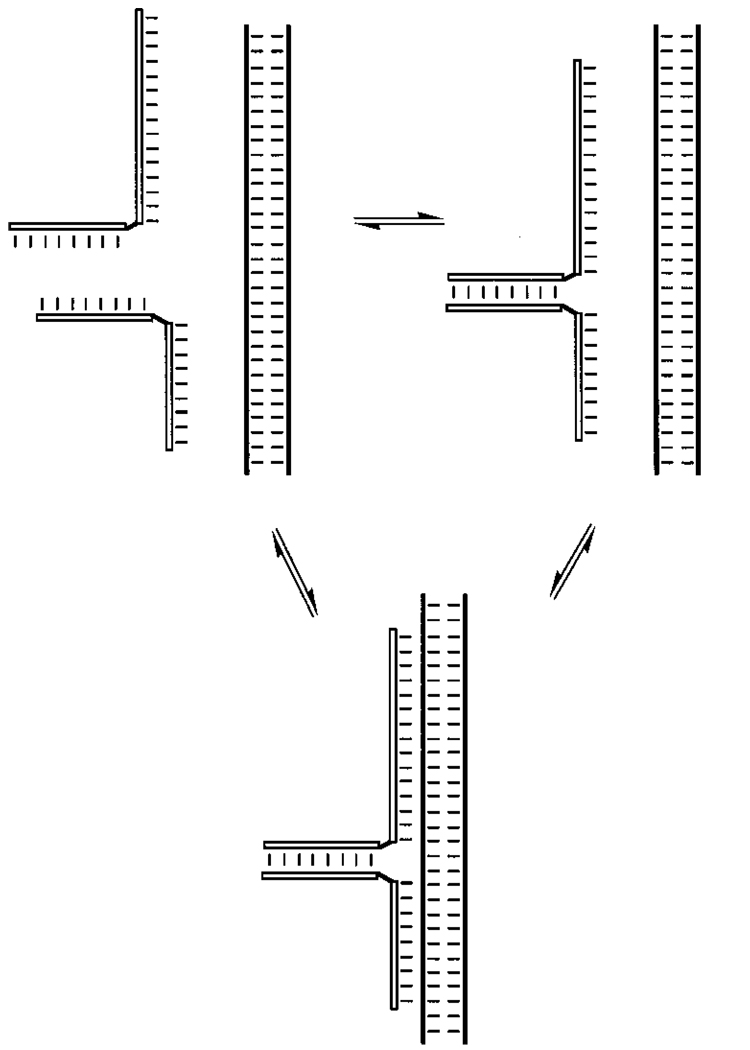

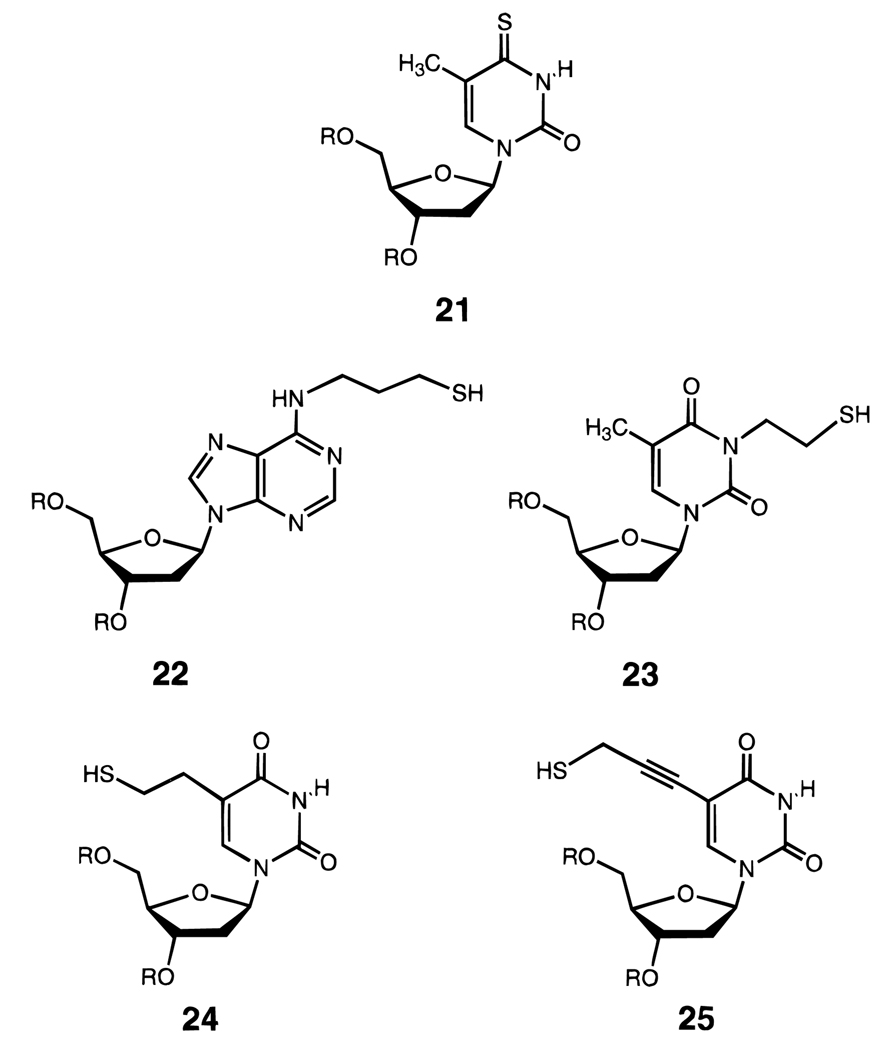

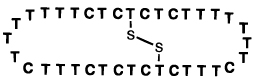

1. Disulfide-Cross-Linked DNA

Several research groups have successfully engineered thiol groups into DNA for the purpose of disulfide cross-linking (Figure 14).91–96 If the thiols are placed into opposite strands of a duplex-forming sequence, the duplex is linked covalently by oxidation and becomes stabilized thermodynamically, presumably because of the entropic benefit.92 A similar approach can be used to stabilize intramolecular hairpins; this has the added advantage of organizing the conformation predictably,93,94 since hairpins can be in equilibrium with bulged duplex structures. Such a cross-linked hairpin has been preorganized in this way to enhance affinity with a DNA-binding antibody.96 Bicyclic and related cross-linked structures (see below) represent the first application of cross-linking for preorganization in binding nucleic acid targets.95

Figure 14.

Examples of five different nucleoside analogues (21–25) which allow disulfide formation in DNA.91–95

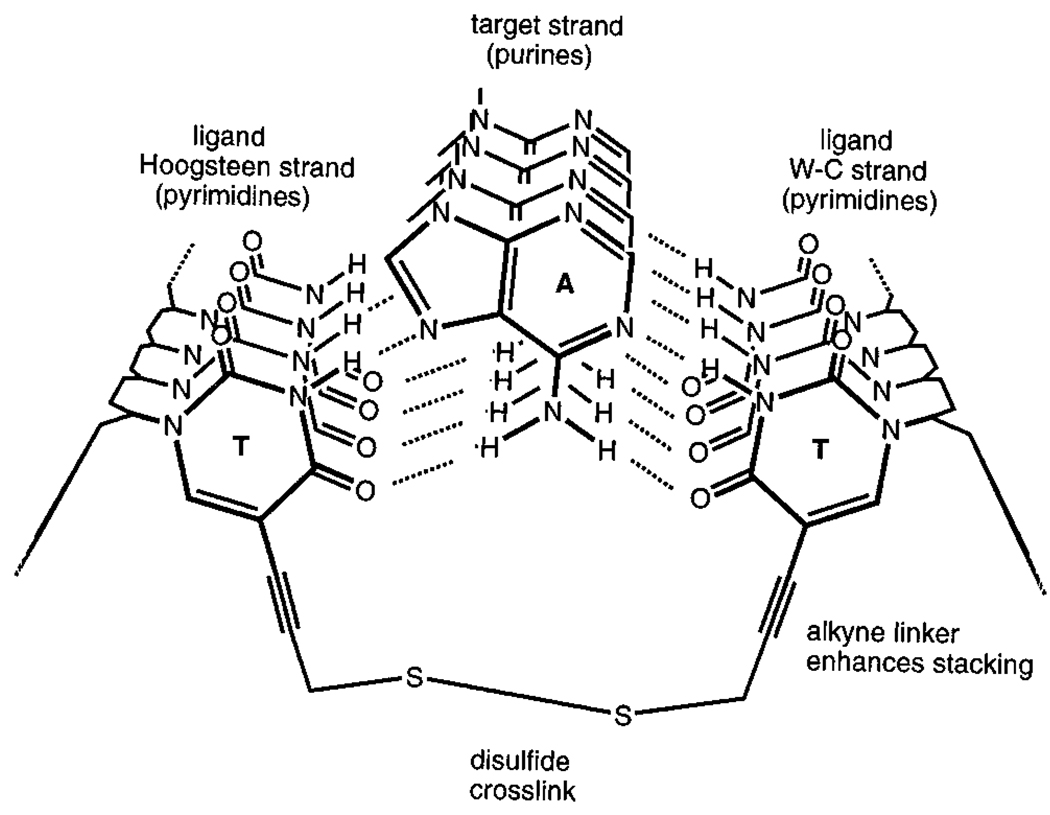

2. Triplex Formation on Single-Stranded Targets

Triple-helical nucleic acid structures (Figure 1) have been known since 1957.97 A purine DNA base can form hydrogen-bonded contacts on two sides, one the Watson–Crick face and one termed the Hoogsteen face. Thus, in duplex DNA, a purine stretch presents sites in the major groove for Hoogsteen complexation by a third strand.98,99 In 1991 it was realized by two different research groups that single-stranded DNA can also serve as a target for triple helix formation: a purine stretch can be bound on two sides by a molecule carrying both a Watson–Crick complementary domain and a Hoogsteen complementary domain.82,100,101 This brings ample opportunities for linking such domains to gain preorganization.

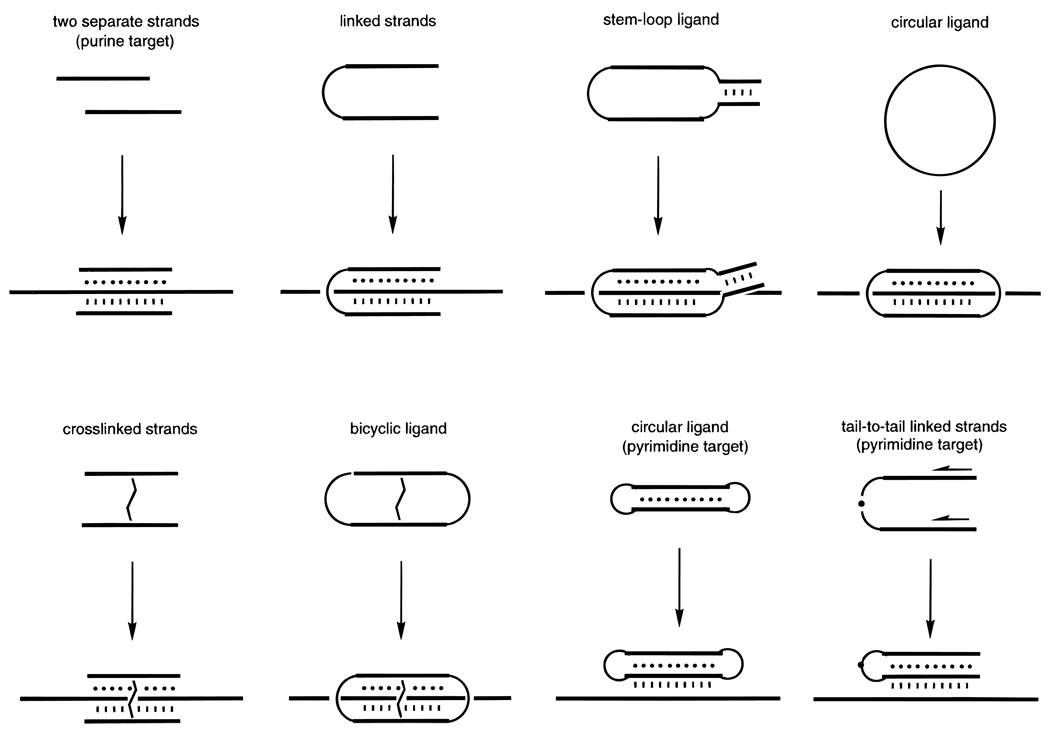

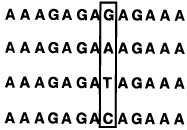

a. Clamp or Fold-Back Oligonucleotides

The simplest way to link two such triplex-forming domains (Figure 15, Table 2) is to connect them with extra nonpairing nucleotides102 or by a simple nonnucleotide linker such as hexaethylene glycol.101 Hélène and co-workers in 1991 and 1993 described the cooperative binding by such a “clamp”-like ligand relative to binding of separate Watson–Crick and Hoogsteen domains; for example, two linked 16+18 mer sequences had a single Tm of 42 °C, whereas without the linkage there were two Tm’s observed, at 35 and 48 °C. The same group showed that such a strategy, combined with attachment of an intercalator, results in high enough affinity to inhibit the progression of a DNA polymerase enzyme along the target.102 Later work by Agrawal and co-workers has led to similar results with “fold-back” (similar to clamp) structures.103,104 Other approaches for the linking of two binding domains and forming similar triplexes have been reported recently.105–107

Figure 15.

Strategies for preorganization of two binding domains in recognition of single-stranded DNA or RNA targets by triplex formation (Watson–Crick binding is denoted by lines and Hoogsteen binding by dots). In general, the greater the number of links between the two binding domains, the greater the rigidity of the ligand, and the greater the affinity and selectivity is. See text for descriptions of and references for these strategies.

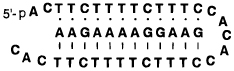

Table 2.

Thermal Melting Data for Complexes of Linear, Clamp, and Circular Oligonucleotides with the Target Sequence 5′-dAAGAAAAGAAAG at pH 7.0, 100 mM Na+, 10 mM Mg2+110

| ligand type | complex | Tm.°C |

|---|---|---|

| ligear | 43.8°C | |

| clamp |  |

54.9 |

| circular |  |

62.3 |

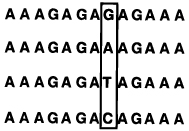

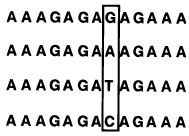

b. Circular and Looped Oligonucleotides

The clamp or fold-back strategy for triplex formation illustrates the linking of two binding domains to increase preorganization. At the same time Hélène was developing the clamp approach, Kool et al. reported the strategy of using circular oligonucleotides to form triplexes on single-stranded targets. 82,100 This is a related approach but instead of a single linkage at one end of the complex, there are two loops linking both ends (Figure 15, Table 2). This has been carried out with nucleotide loops as well as (more recently) nonnucleotide linkers.108,109 The presence of two rather than one linkage results in higher binding affinity. For example, Prakash and Kool found that while a clamp-like oligonucleotide bound a target sequence with an 11 °C advantage in Tm, closure of the clamp into a full circle gave a 19 °C advantage (Table 2).110 Comparison of linker types, lengths, and sequences for clamp-type or circular ligands has established that these factors can greatly affect the affinity of binding a complementary strand of DNA.109

Measurement of the thermodynamics of binding by a circular triplex-forming oligonucleotide showed that a circular oligonucleotide could have a 7 kcal/mol advantage in binding over standard Watson–Crick linear oligonucleotides.100 Importantly, the same modified DNA was measured for its sequence selectivity, as defined by the difference in free energies of binding the correct sequence relative to targets that are mismatched by only one nucleotide.82 It was established that while a linear oligonucleotide has 3–4 kcal of selectivity, a circular oligonucleotide demonstrated 6–7 kcal/mol of selectivity on the same targets. (See Table 3 for an additional example.) This was the first demonstration that such a preorganization strategy could not only increase affinity but greatly enhance selectivity as well. This increased selectivity arises from interrelated effects: first, the increased entropic preorganization leads to greater rigidity and cooperativity; second, in the triplex binding, a mismatched base in the target causes disruption in two, instead of one, binding domains; and third, protonation of cytosine in triplexes has been shown to enhance selectivity as well.34

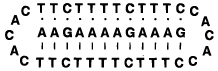

Table 3.

Selectivities of Linear, Circular, and Bicyclic Oligonucleotides, As Measured by Free Energy Differences (ΔΔG°37) between Binding Correct and Singly-Mismatched Targets as Shown (See Ref 95)a,b

| pH=7.0 | selectivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ligand | targets | |||

| Tm(°C) | −ΔG°37 (kcal/mol) | ΔΔG°37 (kcal/mol) | ||

|

T T T C T C T C T C T T T (Watson–Crick complement) | ||||

|

45.1 | 10.7 | -- | |

| 25.0 | 5.5 | 5.2 | ||

| 27.4 | 5.8 | 4.9 | ||

| 23.7 | 5.1 | 5.6 | ||

| ||||

|

54.7 | 17.5 | -- | |

| 35.8 | 8.3 | 9.2 | ||

| 36.3 | 8.5 | 9.0 | ||

| 37.3 | 8.9 | 8.6 | ||

| ||||

|

64.3 | 25.2 | -- | |

| 49.1 | 13.4 | 11.8 | ||

| 48.2 | 14.4 | 10.8 | ||

| 49.1 | 15.2 | 10.0 | ||

Conditions: 1.5 µM concentration each strand, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na•PIPES buffer.

Error limits for individual measurements are estimated at ±0.5 °C in Tm and ±5–10% in free energy.

It has not escaped the attention of several research groups that circular oligonucleotides have another property which can lend advantages in certain applications. In biological and biomedical applications, DNAs are commonly found to be degraded rapidly by nuclease enzymes, and primarily by exonucleases which cleave DNA from the ends. Circular oligonucleotides have no ends and thus can be considerably more resistant to such degradation.108,85,111

c. Cross-Linked Oligonucleotides

The clamp and circular oligonucleotide approaches are strategies in which two DNA-binding domains are linked at their end or ends. Another approach would be to link them across the center. Examination of the base triads involved in triple-helix formation shows that a bridge can easily link two C-5 positions on pyrimidines in opposite strands (Figure 16). Chaudhuri et al. designed a simple thiopropyne-substituted thymidine nucleoside which could position two thiols such that a cross-link could form between the two noncomplementary pyrimidine strands.95 This gives a molecule having the form of an “H”, with the two linked strands being preorganized to form a cooperative triple helical complex with a complementary strand. The experimental results showed that such a cross-linked molecule binds a target strand more strongly than a clamp-type oligonucleotide does with the same target.

Figure 16.

Strategy for cross-linking opposing pyrimidine strands in a triple helix. Shown is a short segment of a triplex in cross section, illustrating how two pyrimidine strands can be bridged by a disulfide linkage to yield a stronger-binding preorganized ligand for the purine (central) strand.95

d. Bicyclic Oligonucleotides

The concept of using a circular oligonucleotide as a ligand for triplex formation on a single-stranded target nucleic acid has been quite successful in improving affinity and sequence selectivity. However, a circular single-stranded oligonucleotide in the ~ 30–40 nt size range still remains quite flexible, with a good deal of room for improvement in preorganization. Chaudhuri et al. therefore combined the circular DNA strategy with the above disulfide-cross-linking strategy (Figure 16), producing a bicyclic oligonucleotide which is composed of a DNA circle with a disulfide link across the center.95 Thermal denaturation studies showed that this bicyclic ligand binds a complementary DNA strand with extremely high affinity; for example, at neutral pH it binds the complement with a free energy 15 kcal/mol more favorable than a Watson–Crick complement alone and 8 kcal/mol more strongly than the circle lacking the extra cross-link (Table 3).

Sequence selectivity was also found to benefit from this additional preorganization strategy (Table 3).95 Measurement of the thermodynamic ability to discriminate against a single mismatch in the target revealed a preference of a very high 10–12 kcal/mol for the correct target. This is believed to be the highest DNA sequence selectivity observed for any molecule to date, and serves as a good example of how selectivity and high affinity are not mutually exclusive.

e. Extension to Pyrimidine Targets

A second motif for triplex formation has been known for some time. This is the so-called purine motif, in which purine–purine–pyrimidine base triads are formed.112,113 As with the previous motif, a purine strand is in the middle, with two other strands forming hydrogen-bonded contacts. In such a motif, one may consider the Watson–Crick complementary pyrimidine strand the target and the other two as binding domains which might be preorganized by linking. Mirkin et al. have shown that a fold-back-type ligand binding by this mode can inhibit a DNA polymerase during replication.114 Kool and co-workers took this a step further by constructing circular DNAs in which the two domains are linked at both ends (Table 4). Such circular DNAs bind both DNA and RNA targets with elevated affinity; for example, a circular 26 mer binds a 12mer C,T-containing target with a free energy of −17 kcal/mol, while a standard Watson–Crick complement binds with a free energy 3.0 kcal/mol less favorable (Table 4).115,116 This approach expands the number of possible natural target sequences available for binding by triplex formation.

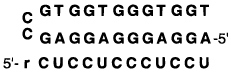

Table 4.

The Effect of Ligand Structure on the Binding of an RNA Strand (Sequence rCUCCUCCCUCCU) Shown Are Melting Transition Temperatures (Tm (°C)) and Free Energies (−ΔG° (kcal/mol)) at pH 7.0a

Conditions: 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Na•PIPES, pH 7.0, 1.5 µM each DNA strand.

Error in Tm values and in free energies are estimated at ±1.0 °C and ±10%, respectively.

f. Unlinked Domains

Two separate molecules can act as ligands for one molecule without even contacting each other, and still do so with a measure of cooperativity in certain instances. For example, a sequence of C,T-containing peptide nucleic acid will not bind a purine complementary sequence of DNA by formation of a duplex, but will instead proceed to form a three-stranded complex in which two PNA strands clamp the target DNA (Figure 17).28 Thus the three-stranded complex is favored energetically over the two-stranded one. This probably occurs because binding of the first PNA strand induces a conformation in the DNA which further favors the next binding event.64 However, in such a complex there is still an entropic cost for bringing the three molecules together, and physical linking of the two PNA strands in a clamp-type ligand (see above) gives even higher affinity.117

3. Tethered DNAs

As pointed out in some of the above strategies, it is often advantageous in many applications to link multiple binding domains together. For maximum cooperativity, a rigid linking domain would perhaps be ideal, and yet to date, most reports of tethered oligonucleotide domains have utilized flexible linkers. Although flexible linkers may not maximize affinity and selectivity, they have shown utility in some applications. Flexible tethers have been used to link two DNA-binding sequences for hybridization to separated sites in single-stranded RNAs118 and also to duplex DNAs.119–121 In the RNA-binding case this strategy allowed the recognition of sites which are near in space but separated in sequence on a folded RNA target. In the case of duplex DNA recognition this can allow the recognition of purine runs separated by non-homopurine segments119,120 or the recognition of adjacent purine runs in opposite strands of a duplex.121

VI. Summary and Prospects for the Future

It is becoming increasingly evident that preorganization strategies can lend great benefits in the recognition of nucleic acids by oligonucleotides. Even the most advanced molecular examples of preorganized oligonucleotides in existence, however, still are quite flexible by the standards of the more classical guest–host recognition field. Thus it seems likely that considerably greater improvements in the binding properties of modified DNAs are to be anticipated. It should also be pointed out that there are other chemical strategies for improving molecular properties of DNA which are not directly related to the entropic arguments presented here. For example, many other DNA backbone replacements have been synthesized which increase lifetime in biological media,1,2 and conjugated groups have been added to enhance binding or cellular uptake.3 Such strategies are complementary to most of those presented here, and thus combining these varied features in future generations of molecules will no doubt give further improvements in properties. Finally, the widespread and increasingly important applications of modified DNAs are still at an early stage of development, and the availability of improved molecular properties such as those described here will only aid in this development in the future.

Acknowledgments

I thank my co-workers for their effort and enthusiasm. I also thank the National Institutes of Health (GM46625 and GM52956), the Army Research Office, and the Office of Naval Research for support of various aspects of our work in preorganization of oligonucleotides.

Biography

Eric Kool was born on November 8, 1960, in Evanston, IL. He pursued his undergraduate degree in chemistry at Miami University in Oxford, OH. In his graduate work he studied with Professor R. Breslow as an NSF Predoctoral Fellow at Columbia University in New York, where he obtained his Ph.D. degree in 1988. He then worked with Professor P. B. Dervan at the California Institute of Technology as an NIH Postdoctoral Fellow. In 1990 he joined the Chemistry Department at the University of Rochester, where he is now Professor of Chemistry and also Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics. His research interests fall in the general area of organic chemistry of biomolecules, with specific interests in molecular recognition of nucleic acids and proteins, design of molecules which mimic the structure and function of biomolecules, and the construction of self-assembling and self-replicating systems.

References

- 1.Gait MJ, editor. Oligonucleotide Synthesis. Oxford: IRL Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaucage SL, Iyer RP. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:2223. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaucage SL, Iyer RP. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:1925. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JS, editor. Oligodeoxynucleotides: Antisense Inhibitors of Gene Expression. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhlmann E, Peyman A. Chem. Rev. 1990;90:543. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baserga R, Denhardt DT, editors. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. Vol. 660. 1992. Antisense Strategies; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milligan JF, Matteucci MD, Martin JC. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:1923. doi: 10.1021/jm00066a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaucage SL, Caruthers MH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1859. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Usman N, Ogilvie KK, Jiang M-Y, Cedergren RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:7845. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton RG. Mutat. Res. 1993;285:125. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90060-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cram DJ. Chemtech. 1987;17:120. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jencks WP. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1975;43:219. doi: 10.1002/9780470122884.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Vinogradov SN, Linnell RH. Hydrogen Bonding. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1971. pp. 124–135. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones DAK, Watkinson JG. J. Chem. Soc. 1964:2366. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccirilli JA, Krauch T, Moroney SE, Benner SA. Nature. 1990;343:33. doi: 10.1038/343033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pranata J, Wierschke SG, Jorgensen WL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2810. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freier SM, Sugimoto N, Sinclair A, Alkema D, Nielson T, Kierzek R, Caruthers MH, Turner DH. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3214. doi: 10.1021/bi00359a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner DH, Sugimoto N, Freier SM. In: Nucleic Acids. Saenger W, editor. Subvolume C. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman RA, Honig B. Biopolymers. 1992;32:145. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maroun RC, Olson WK. Biopolymers. 1988;27:585. doi: 10.1002/bip.360270404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarai A, Mazur J, Nussinov R, Jernigan RL. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8498. doi: 10.1021/bi00422a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter CA. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:1025. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe MJ, Schellman MJ. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;65:91. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard NJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979;12:423. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deslongchamps G, Murray BA, Rebek J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:797. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newcomb LF, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guckian K, Schweitzer BA, Ren X-F, Sheils CJ, Paris PL, Tahmassebi DC, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8182. doi: 10.1021/ja961733f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning GS. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1978;11:179. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.T’so POP, Miller PS, Aurelian L, Murakami A, Agris C, Blake KR, Lin SB, Lee BL, Smith CC. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987;507:220. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb45804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Berg R, Buchardt O. Science. 1991;254:1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto H, Nelson MG, Switzer C. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:4194. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dempcy RO, Browne KA, Bruice TC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersheim M, Turner DH. Biochemistry. 1983;22:256. doi: 10.1021/bi00271a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breslauer KJ, Freire E, Straume M. Methods Enzymol. 1992;211:533. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)11030-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Friedman A, Kool ET. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9774. doi: 10.1021/bi00030a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rougée M, Faucon B, Mergny JL, Barcelo F, Giovannangeli C, Montenay-Garestier T, Hélène C. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9269. doi: 10.1021/bi00153a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates PJ, Dosanjh HS, Kumar S, Jenkins TC, Laughton CA, Neidle S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3627. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) Breslauer KJ, Frank R, Blocker H, Marky LA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:3746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) SantaLucia J, Allawi HT, Seneviratne PA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3555. doi: 10.1021/bi951907q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Senior M, Jones RA, Breslauer KJ. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3879. doi: 10.1021/bi00410a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams DH. Aldrichimica Acta. 1991;24:71. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Searle MS, Williams DH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2051. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maher LJ, III, Dervan PB, Wold B. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8820. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faucon B, Mergny J-L, Hélène C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3181. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.16.3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner RW, Matteucci MD, Lewis JG, Gutierrez AJ, Moulds C, Froehler BC. Science. 1993;260:1510. doi: 10.1126/science.7684856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herschlag D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:6921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asseline U, Delarue M, Lancelot G, Toulme F, Thuong NT, Montenay-Garestier T, Hélène C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:3297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun JS, Francois JC, Montenay-Garestier T, Saison-Behmoaras T, Roig V, Thuong NT, Hélène C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:9198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barszcz D, Shugar D. Eur. J. Biochem. 1968;5:91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, Woodsworth ML, Latimer LJP, Morgan AR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:6603. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.16.6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xodo LE, Manzini G, Quadrifoglio F, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5625. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.(a) Povsic TJ, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;111:3059. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sanghvi YS, Hoke GD, Freier SM, Zounes MC, Gonzalez C, Cummins L, Sasmor H, Cook PD. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3197. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, Kool ET. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4125. doi: 10.1021/bi00012a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sowers LC, Shaw BS, Sedwick WD. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987;148:790. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Xu Y, Kool ET. BioMed. Chem. 1997 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Froehler BC, Wadwani S, Terhorst TJ, Gerrard SR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5307. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sagi J, Szemzo A, Ebinger K, Szabolcs A, Sagi G, Ruff E, Otvos L. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2191. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Froehler BC, Jones RJ, Cao X, Terhorst TJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1003. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colocci N, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:785. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seela F, Thomas H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1995;78:94. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gutierrez AJ, Terhorst TJ, Matteucci MD, Froehler BC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5540. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue H, Imura A, Ohtsuka E. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7119. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.19.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin K-Y, Jones RJ, Matteucci M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3873. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ren X-F, Schweitzer BA, Sheils CJ, Kool ET. Angew. Chem. 1996;108:834. doi: 10.1002/anie.199607431. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1996, 35, 743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guckian K, Ren X-F, Chaudhuri NC, Kool ET. 1997 in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Buchardt O. Bioconjugate Chem. 1994;5:3. doi: 10.1021/bc00025a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Mesmaeker A, Waldner A, Sanghvi Y, Lebreton J. BioMed. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:395. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tarkoy M, Bolli M, Schweizer B, Leumann C. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1993;76:481. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarkoy M, Leumann C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993;32:1432. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bolli M, Leumann C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:694. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eschenmoser A, Dobler M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1992;75:218. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pitsch S, Wendeborn S, Jaun B, Eschenmoser A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1993;76:2161. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pitsch S, Krishnamurthy R, Bolli M, Wendeborn S, Holzner A, Minton M, Leseuer C, Schlonvogt I, Jaun B, Eschenmoser A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1995;78:1621. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Augustyns K, Vandendriessche F, Van Aerschot A, Busson R, Urbanke C, Herdewijn P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4711. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.18.4711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Aerschot A, Verheggen I, Hendrix C, Herdewijn P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:1338. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Erie DA, Jones RA, Olson WK, Sinha NK, Breslauer KJ. Biochemistry. 1989;28:268. doi: 10.1021/bi00427a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ashley GA, Kushlan DM. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2927. doi: 10.1021/bi00225a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doktycz MJ, Goldstein RF, Paner TM, Gallo FJ, Benight AS. Biopolymers. 1992;32:849. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.(a) de Vroom E, Broxterman HJ, Sliedregt LA, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:4607. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.10.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rao MV, Reese CB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8221. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dolinnaya NG, Blumenfeld M, Merenkova IM, Oretskaya TS, Krynetskaya NF, Ivanovskaya MG, Vasseur M, Shabarova ZA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5403. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.23.5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rubin E, Rumney S, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3547. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Capobianco ML, Carcuro A, Tondelli L, Garbesi A, Bonora GM. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2661. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.9.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DeNapoli L, Messere A, Montesarchio D, Piccialli G, Santacroce C. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1993;12:21. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6265. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ryan K. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Rochester; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fedorova OA, Gottikh MV, Romanova EA, Oretskaia TS, Dolinnaia NG, Shabarova ZA. Mol. Biol. 1995;29:1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang S, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2326. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nilsson M, Malmgren H, Samiotaki M, Kwiatkowski M, Chowdhary BC, Landegren U. Science. 1994;265:2085. doi: 10.1126/science.7522346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Colocci N, Distefano MD, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:4468. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Distefano MD, Shin JA, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5901. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Distefano MD, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:11006. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Colocci N, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:785. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lipsett MN. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1966;31:449. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1966.031.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferentz AE, Verdine GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4000. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Glick GD, Osborne SE, Knitt DS, Marino JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5447. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goodwin JT, Glick GD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:5549. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chaudhuri NC, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10434. doi: 10.1021/ja00147a004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stevens SY, Swanson PC, Voss EW, Glick GD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:1585. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Felsenfeld G, Davies DR, Rich A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957;79:2023. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moser HE, Dervan PB. Science. 1987;238:645. doi: 10.1126/science.3118463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.LeDoan T, Perrouault L, Praseuth D, Habhoub N, Decout JL, Thuong NT, Lhomme J, Hélène C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:7749. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.19.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Prakash G, Kool ET. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1991:1161–1163. doi: 10.1039/C39910001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Giovannangeli C, Montenay-Garestier T, Rougée M, Chas-signol M, Thuong NT, Hélène C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7775. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Giovannangeli C, Thuong NT, Hélène C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kandimalla ER, Agrawal S. Gene. 1994;149:115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kandimalla ER, Agrawal S, Vekataraman G, Sasisekharan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6416. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gryaznov SM, Lloyd DH. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5909. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hudson RHE, Damha MJ. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1993;29:97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salunkhe M, Wu T, Letsinger RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:8768. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rumney S, Kool ET. Angew. Chem. 1992;104:1686. doi: 10.1002/anie.199216171. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rumney S, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5635. doi: 10.1021/ja00126a004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Prakash G, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:3523. doi: 10.1021/ja00035a056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Clusel C, Ugarte E, Enjolras N, Vasseur M, Blumenfeld M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3405. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Marck C, Thiele D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:1017. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.3.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Beal PA, Dervan PB. Science. 1991;251:1360. doi: 10.1126/science.2003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Samadashwily GM, Dayn A, Mirkin SM. EMBO J. 1993;12:4975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang S, Kool ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:8857. doi: 10.1021/ja00098a075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vo T, Wang S, Kool ET. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2937. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.15.2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Knudsen H, Nielsen P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:494. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.3.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cload ST, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6324. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kessler DJ, Pettitt BM, Cheng Y-K, Smith SR, Jayaraman K, Vu HM, Hogan ME. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4810. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.20.4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Horne DA, Dervan PB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2435. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhou B, Puga E, Sun J-S, Garestier T, Hélène C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10425. [Google Scholar]