Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

Methods

One hundred forty-seven patients were investigated.

Results

As initial treatment, 25 patients received UDCA (300–600 mg/day) monotherapy (UDCA group), 40 received a combination of prednisolone (PSL) (≥20 mg/day) and UDCA (combination group), 68 received PSL monotherapy (PSL group), and 14 received other treatments. During the follow-up, in the UDCA group, PSL was added to 8 of 12 patients failing to achieve the normalization of serum transaminase levels with UDCA monotherapy. Cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum transaminase levels was 64% in the UDCA group, 95% in the combination group, and 94% in the PSL group (log-rank test, P = 0.0001). UDCA group required longest periods until the normalization of serum transaminase levels. Eleven patients, who achieved persistent normalization of serum transaminase levels with UDCA monotherapy, did not reach liver failure or develop hepatocellular carcinoma for 49.7 (range = 13.4–137.3) months. Meanwhile, during the taper of PSL, doses of PSL at the initial relapse were lower in patients treated with PSL and UDCA than in those treated with PSL monotherapy, and initial relapse occurred earlier in patients treated with PSL monotherapy.

Conclusions

UDCA monotherapy is effective for some Japanese AIH patients; however, UDCA monotherapy for patients with either high-grade inflammatory activity or poor residual capacity of liver function is not recommended because they may reach liver failure before achievement of remission. Meanwhile, additional use of UDCA during the taper of corticosteroids may be effective for the prevention of early relapse.

Keywords: Autoimmune hepatitis, Ursodeoxycholic acid, Corticosteroid

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is generally responsive to immunosuppressive treatment, and corticosteroids are commonly used for initial and maintenance treatment [1]. Approximately 90% of patients can achieve the normalization of serum transaminase levels within 6 months after the introduction of corticosteroid treatment [2] that leads to the improvement of histological activity and staging, even in patients with cirrhosis [3]. With appropriate immunosuppressive treatment, the 10-year survival rate is reported at more than 90% regardless of histological staging [4].

However, prolonged use of corticosteroids leads to the development of adverse events (osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and Cushing’s syndrome). On the other hand, rapid taper of corticosteroids leads to relapse and multiple relapses are associated with hepatic death and liver transplantation [5]. Relapse occurs in approximately 90% of patients within 1 year after immunosuppressive treatment withdrawal, especially in approximately 50% of patients within 3 months. These are dilemmas in clinical practice.

In a previous report [6], ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), which is a hydrophilic dihydroxy bile acid and effects the protection of hepatocytes against bile acid-induced apoptosis, stimulation of impaired hepatobiliary secretion, and protection of cholangiocytes against the toxic effects of hydrophobic bile acids [7], improved serum transaminase levels and histological activities in Japanese AIH patients; however, the study population was too small. In another report [8], short-term treatment with UDCA did not facilitate reduction in either the dose of corticosteroids or histological activity in white patients with intractable AIH. It has been controversial whether UDCA has a beneficial therapeutic effect in AIH patients.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the efficacy of UDCA treatment in Japanese AIH patients. We evaluated the normalization of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels under UDCA treatment and the association between dose reduction of corticosteroids under the additional use of UDCA and relapse of the disease.

Materials and methods

Patients

One hundred seventy-one Japanese AIH patients (148 females, median age 55 [16–79] years) were admitted to the Okayama University Hospital or one of six affiliated hospitals between March 1989 and June 2007. All patients who were seronegative for hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-hepatitis C virus antibody, hepatitis C virus-RNA, and antimitochondrial antibody underwent liver biopsy. A diagnosis of AIH was made according to the revised scoring system proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) [9]. A definite diagnosis of AIH based on this revised scoring system required a pretreatment score exceeding 15, whereas a probable diagnosis required a score between 10 and 15. Patients with an overlapping syndrome or a coexistent liver disease (e.g., primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or alcohol-induced liver injury) were excluded from this analysis.

In this study, 24 of the 171 patients (14%) were transferred to other hospitals without follow-up. Thus, 147 patients (86%) were included in the present analysis.

Criteria for acute presentation

An acute presentation was defined by the presence of acute onset of symptoms (e.g., jaundice and/or fatigue and/or anorexia) in conjunction with bilirubin levels of 5 mg/dL or more and/or serum ALT levels higher than 10-fold the upper normal limit.

Histological evaluation

Liver biopsy was performed with a Vim-Silverman needle (14-G) under laparoscopy or with a 17-G needle under ultrasonography guidance, before or just after commencing treatment. Liver biopsy specimens were evaluated by two pathologists and diagnosed as acute or chronic hepatitis. A diagnosis of acute hepatitis was made on the basis of the presence of histologically predominant zone 3 necrosis with minimal lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration into portal tracts, in the absence of interface hepatitis or portal fibrosis. Liver biopsy specimens diagnosed as chronic hepatitis underwent histological staging based on the classification of Desmet et al. [10].

Treatment

The standard initial treatment was prednisolone (PSL) (30–40 mg/day) with or without UDCA (300–600 mg/day). In patients with histological low-grade inflammatory activity, the initial treatment was low-dose PSL (20 mg/day) with or without UDCA (300–600 mg/day). Elderly patients with histological low-grade inflammatory activity and comorbidities such as osteoporosis and/or diabetes were treated with UDCA (300–600 mg/day) with or without lower doses of PSL (<20 mg/day). An initial treatment was defined as any therapy that was started within 3 months after the diagnosis of AIH. It was continued until the normalization of serum ALT levels.

After the normalization of serum ALT levels, PSL was tapered by 2.5–5 mg every 1 or 2 weeks to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/day or less. When an incomplete response to initial treatment or relapse was observed, PSL was added or increased or UDCA (300–600 mg/day) and/or azathioprine (50–100 mg/day) were added.

Follow-up

Each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical review and physical examination at each follow-up visit. Conventional laboratory blood tests were performed every 1–3 months.

Criteria for the relapse of AIH

Relapse was defined as an increase in serum ALT levels to more than twofold the upper normal limit following the normalization of serum ALT levels with medical treatment.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical program (release 11.0.1 J, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Continuous variables were expressed as medians and ranges. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences in the continuous variables between two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was carried out among three groups. Dichotomous variables were compared by the χ2 test. Cumulative incidence was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and significance was determined by the log-rank test. The values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical features of 147 AIH patients

One hundred twenty-seven patients (86%) were female, and the median age was 55 (16–79) years. On the basis of the revised scoring system proposed by IAIHG [9], the median pretreatment score was 18 (10–21). One hundred fifteen patients (78%) were diagnosed as definite AIH patients. Forty-one patients (28%) showed acute presentation. Thirty-seven patients (25%) had concurrent autoimmune diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Concurrent autoimmune diseases in 147 patients with autoimmune hepatitis

| Disease | Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 15 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 3 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3 |

| Graves’ disease | 3 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 3 |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 2 |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | 2 |

| Progressive systemic sclerosis | 2 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis + autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 1 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus + Sjögren’s syndrome | 1 |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis + Sjögren’s syndrome | 1 |

One hundred twenty-two patients (83%) were positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) (≥1:40). Of the 109 patients screened, 72 (66%) were positive for smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) (≥1:40). One hundred thirty-nine of 147 patients (95%) were positive for ANA and/or SMA. Of the 70 patients who were screened for HLA DR status, 49 (70%) had DR4. None had DR3.

Histological acute hepatitis and cirrhosis were observed in 10 (7%) and 12 patients (8%), respectively. Rosetting of liver cells and zone 3 necrosis were observed in 38 (26%) and 47 patients (32%), respectively.

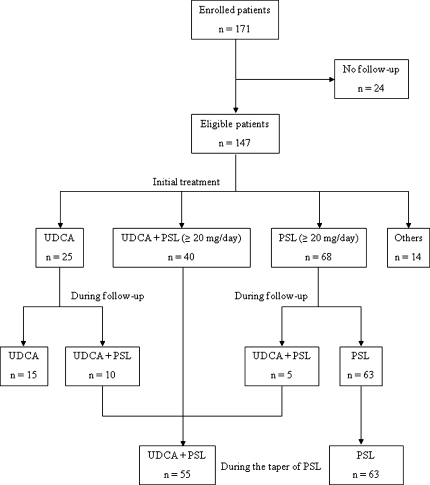

As initial treatment, of the 147 patients, 25 received UDCA monotherapy (300–600 mg/day) (UDCA group), 40 received a combination of PSL (≥20 mg/day) and UDCA (300–600 mg/day) (combination group), 68 received PSL monotherapy (≥20 mg/day) (PSL group), and 14 received other treatments (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical course of study population

Comparison of clinical features among three groups classified according to initial treatment

UDCA group had lowest serum levels of bilirubin, transaminase, and immunoglobulin G (IgG) and highest serum albumin levels among the three groups. However, there were no differences in the frequencies of positivity for ANA or SMA, HLA DR4, and the histological features (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical features of the three groups classified according to initial treatment

| UDCA (n = 25) | Combination (n = 40) | PSL (n = 68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female), n (%) | 22 (88) | 33 (83) | 59 (87) | 0.78 |

| Age (years) | 62 (37–77) | 52 (18–78) | 52 (16–79) | 0.03 |

| International diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis | ||||

| Pretreatment score | 17 (10–20) | 17 (11–20) | 18 (10–21) | 0.03 |

| Definite diagnosis, n (%) | 17 (68) | 33 (83) | 54 (79) | 0.36 |

| Acute presentation, n (%) | 4 (16) | 17 (43) | 19 (28) | 0.07 |

| Concurrent autoimmune disease, n (%) | 3 (12) | 4 (10) | 22 (32) | 0.01 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.3–29.2) | 1.4 (0.4–24.3) | 1.1 (0.4–17.1) | 0.0001 |

| AST (IU/L) | 96 (33–1,502) | 388 (43–1,704) | 187 (37–2,330) | 0.0005 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 98 (28–1,433) | 407 (36–1,450) | 229 (26–2,161) | 0.0004 |

| ALP, ×ULN | 1.0 (0.6–2.6) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 1.1 (0.3–5.1) | 0.02 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.0 (3.0–5.1) | 3.7 (2.4–4.4) | 3.8 (2.7–4.7) | 0.04 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 2,134 (1,085–3,970) | 2,517 (1,300–4,530) | 2,663 (1,170–6,562) | 0.04 |

| ANA (≥1:40), n (%) | 22 (88) | 30 (75) | 57 (84) | 0.35 |

| SMA (≥1:40), n (%) | 9/14 (64) | 22/31 (71) | 38/52 (73) | 0.81 |

| HLA DR4, n (%) | 6/11 (55) | 16/23 (70) | 25/34 (74) | 0.50 |

| Histological finding | ||||

| Staging, n (%) | 0.80 | |||

| Acute hepatitis | 1 (4) | 4 (10) | 5 (7) | |

| Chronic hepatitis | ||||

| F1 | 7 (28) | 11 (28) | 16 (24) | |

| F2 | 7 (28) | 11 (28) | 25 (37) | |

| F3 | 8 (32) | 9 (22) | 19 (28) | |

| F4 | 2 (8) | 5 (12) | 3 (4) | |

| Rosetting of liver cells, n (%) | 6 (24) | 13 (33) | 18 (26) | 0.71 |

| Zone 3 necrosis, n (%) | 5 (20) | 17 (43) | 25 (37) | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: UDCA ursodeoxycholic acid, PSL prednisolone, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, IgG immunoglobulin G, ANA antinuclear antibody, SMA smooth muscle antibody, HLA human leukocyte antigen, ULN upper limit of normal

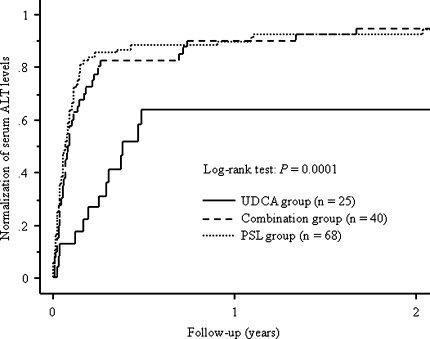

The follow-up durations were 73.5 (12.2–149.3) months in the UDCA group, 65.1 (12.2–162.3) months in the combination group, and 79.1 (17.2–204.2) months in the PSL group, respectively (P = 0.14). Cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum ALT levels was 64% in the UDCA group, 95% in the combination group, and 94% in the PSL group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum ALT levels. The follow-up durations were 73.5 (12.2–149.3) months in 25 patients initially treated with UDCA monotherapy (UDCA group), 65.1 (12.2–162.3) months in 40 patients initially treated with a combination of PSL and UDCA (combination group), and 79.1 (17.2–204.2) months in 68 patients initially treated with PSL monotherapy (PSL group), respectively. Cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum ALT levels was 64% in the UDCA group, 95% in the combination group, and 94% in the PSL group (log-rank test, P = 0.0001)

UDCA monotherpay as initial treatment

Of the UDCA group, 12 patients failed to achieve the normalization of serum ALT levels with UDCA monotherapy during the follow-up and PSL was added to eight patients. On the other hand, during the follow-up, in 2 of the 13 patients who once achieved the normalization of serum ALT levels, serum ALT levels fluctuated and PSL was added. Thus, PSL was added to 10 patients of the UDCA group and UDCA monotherapy was continued in the remaining 15 patients (Fig. 1). Eleven of the 15 patients who continued UDCA monotherapy achieved the normalization of serum ALT levels during the follow-up, and none of the 11 patients reached liver failure or developed hepatocellular carcinoma during 49.7 (13.4–137.3) months.

Efficacy of UDCA during the taper of corticosteroids

During the taper of PSL, UDCA was added to five patients of the PSL group. As mentioned above, PSL was added to 10 patients of the UDCA group (Fig. 1). Thus, during the follow-up, 55 patients were treated with a combination of PSL and UDCA and 63 were treated with PSL monotherapy. There were no differences in clinical features at presentation except a frequency of concurrent autoimmune diseases between the two groups (Table 3). There was no difference in follow-up duration between the two groups (follow-up duration; 71.5 [12.2–186.1] months vs. 77.1 [17.2–204.2] months; P = 0.31).

Table 3.

Clinical features of patients treated with a combination of PSL and UDCA or PSL monotherapy during the taper of PSL

| Combination (n = 55) | PSL (n = 63) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female), n (%) | 47 (85) | 54 (86) | 0.97 |

| Age (years) | 53 (16–78) | 52 (16–79) | 0.88 |

| International diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis | |||

| Pretreatment score | 17 (10–20) | 18 (10–21) | 0.07 |

| Definite diagnosis, n (%) | 43 (78) | 50 (79) | 0.88 |

| Acute presentation, n (%) | 19 (35) | 17 (27) | 0.37 |

| Concurrent autoimmune disease, n (%) | 7 (13) | 20 (32) | 0.01 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.2 (0.3–24.3) | 1.1 (0.4–17.1) | 0.34 |

| AST (IU/L) | 278 (43–2,330) | 179 (37–1,716) | 0.46 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 280 (28–1,783) | 229 (26–2,161) | 0.56 |

| ALP, × ULN | 1.2 (0.5–3.8) | 1.1 (0.3–5.1) | 0.30 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 (2.4–4.8) | 3.8 (2.7–4.7) | 0.18 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 2,579 (1,300–5,356) | 2,624 (1,170–6,562) | 0.68 |

| ANA (≥1:40), n (%) | 42 (76) | 52 (83) | 0.41 |

| SMA (≥1:40), n (%) | 24/39 (62) | 36/49 (73) | 0.23 |

| HLA DR4, n (%) | 21/31 (68) | 23/31 (74) | 0.58 |

| Histological finding | |||

| Staging, n (%) | 0.82 | ||

| Acute hepatitis | 5 (9) | 4 (6) | |

| Chronic hepatitis | |||

| F1 | 15 (27) | 16 (25) | |

| F2 | 17 (31) | 22 (35) | |

| F3 | 13 (24) | 18 (29) | |

| F4 | 5 (9) | 3 (5) | |

| Rosetting of liver cells, n (%) | 15 (27) | 16 (25) | 0.82 |

| Zone 3 necrosis, n (%) | 21 (38) | 22 (35) | 0.71 |

Abbreviations: UDCA ursodeoxycholic acid, PSL prednisolone, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, IgG immunoglobulin G, ANA antinuclear antibody, SMA smooth muscle antibody, HLA human leukocyte antigen, ULN upper limit of normal

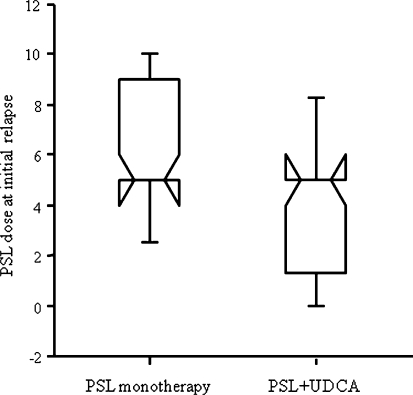

During the follow-up, relapse occurred in 32 of 55 patients (58%) treated with combination treatment and 36 of 63 patients (57%) treated with PSL monotherapy (log-rank test, P = 0.97). In patients with relapse, there was no difference in the duration from the initial normalization of serum ALT level to the initial relapse between the two groups (13.3 [3.0–138.5] months in the combination treatment group vs. 17.1 [1.5–129.0] months in the PSL monotherapy group; P = 0.77). However, doses of PSL at the initial relapse was lower in patients treated with combination treatment than in those treated with PSL monotherapy (5 [0–10] mg/day vs. 5 [0–15] mg/day; P = 0.03) (Fig. 3). During treatment periods with PSL 10 mg/day or more, 7.5 mg/day, and 5 mg/day, relapse occurred in 3, 4, and 21 of 55 patients treated with combination treatment whereas it occurred in 9, 13, and 28 of 63 patients treated with PSL monotherapy (5%, 7%, and 38% vs. 14%, 21%, and 44%; P = 0.49, 0.04, and 0.09).

Fig. 3.

Box plots indicate the median, interquartile range, and 90 percentile range of maintenance doses of PSL at initial relapse. The dose was smaller in patients treated with a combination of PSL and UDCA than in those treated with PSL monotherapy, respectively (5 [0–10] mg/day vs. 5 [0–15] mg/day; P = 0.03)

Discussion

UDCA has some degree of immunomodulating effects. Experimentally, UDCA suppresses the secretion of interleukin-2, interleukin-4, and interferon-γ from activated T lymphocytes and immunoglobulin production from B lymphocytes [11]. Recently, in concanavalin A-induced liver injury, the administration of UDCA before concanavalin A injection has been reported to dose dependently reduce plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 and to inhibit the elevation of plasma transaminase levels and decrease the incidence of liver necrosis [12]. In AIH patients, serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 have been reported to be associated with the disease activity [13, 14]. Furthermore, increased expressions of interleukin-4 and interferon-γ are shown in the liver specimens of AIH patients [15]. Thus, UDCA may control the disease activity of AIH on the basis of these mechanisms.

In this study, 64% of the UDCA group achieved the normalization of serum ALT levels with UDCA monotherapy. So, UDCA monotherapy will be effective in some Japanese AIH patients. However, in this study, patients treated with UDCA monotherapy had lower serum ALT levels at presentation than those treated with PSL. Furthermore, until the normalization of serum ALT levels, longer periods were required in patients treated with UDCA monotherapy than in those treated with PSL. Thus, we consider that UDCA monotherapy for patients with either high-grade inflammatory activity or poor residual capacity of liver function is not recommended because they may reach liver failure before the achievement of remission.

Does UDCA monotherapy improve the prognosis of AIH patients? To improve the prognosis of AIH, persistent normalization of serum transaminase levels is necessary [16, 17]. In this study, none of 11 patients who achieved the normalization of serum ALT levels with UDCA monotherapy reached liver failure or developed hepatocellular carcinoma during the follow-up period. UDCA monotherapy may improve the prognosis of Japanese AIH patients if persistent normalization of serum ALT levels is achieved.

Once remission is achieved with corticosteroid treatment, doses of corticosteroids are gradually tapered. Histological improvement lags behind laboratory improvement by 3–6 months, so maintenance treatment (PSL 0.1–0.2 mg/kg daily or 5 mg daily) for 1–2 years after the normalization of serum transaminase levels is recommended [18]. However, prolonged use of corticosteroids leads to the development of adverse events. This study suggests that the additional doses of UDCA may be useful for the safer taper of corticosteroids and lead to the decrease in the adverse events due to prolonged use of corticosteroids.

It is unclear when to commence UDCA for Japanese AIH patients in order to prevent relapse during the taper of corticosteroids. In this study, there was no difference in cumulative incidence of the normalization of serum ALT levels after the introduction of initial treatment between the PSL and combination groups. Thus, the addition of UDCA to PSL as an initial treatment modality may not be always necessary. On the other hand, in the PSL group, doses of PSL at the initial relapse were 15 mg/day or less. We suggest that the addition of UDCA before the taper of PSL dose to 15 mg/day may be effective for the prevention of relapse.

In conclusion, UDCA monotherapy is effective in some Japanese AIH patients; however, until the normalization of serum transaminase levels, longer periods were required in patients treated with UDCA monotherapy than in those treated with PSL. Thus, we consider that UDCA monotherapy for patients with either high-grade inflammatory activity or poor residual capacity of liver function is not recommended because they may reach liver failure before the achievement of remission. Meanwhile, the additional use of UDCA during the taper of corticosteroid may be effective for the prevention of early relapse. UDCA will be worth using in Japanese AIH patients with both low-grade inflammatory activity and sufficient residual capacity of liver function. To confirm these findings, validation based on randomized trials is required.

Contributor Information

Yasuhiro Miyake, Phone: +81-86-2357219, FAX: +81-86-2255991, Email: miyakeyasuhiro@hotmail.com.

Yoshiaki Iwasaki, Email: yiwasaki@cc.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Haruhiko Kobashi, Email: hkobashi@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Tetsuya Yasunaka, Email: Yasu0328@gmail.com.

Fusao Ikeda, Email: fikeda@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Akinobu Takaki, Email: akitaka@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Ryoichi Okamoto, Email: okamoto6488@yahoo.co.jp.

Kouichi Takaguchi, Email: k.takaguchi@mail.central-hp.pref.kagawa.jp.

Hiroshi Ikeda, Email: hi5206@kchnet.or.jp.

Yasuhiro Makino, Email: makino@iwakuni-nh.go.jp.

Masaharu Ando, Email: m-ando@mx8.tiki.ne.jp.

Kohsaku Sakaguchi, Email: sakaguti@cc.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Kazuhide Yamamoto, Email: kazuhide@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toda G, Zeniya M, Watanabe F, Imawari M, Kiyosawa K, Nishioka M, et al. Present status of autoimmune hepatitis in Japan—correlating the characteristics with international criteria in an area with a high rate of HCV infection. Japanese National Study Group of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(97)80453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Decreased fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:646–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts SK, Therneau TM, Czaja AJ. Prognosis of histological cirrhosis in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:848–857. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montano-Loza AJ, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Consequences of treatment withdrawal in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2007;27:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Yoneda M, Yokohama S, Tamori K, Sato Y, Aso K, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:490–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beuers U. Drug insight: mechanisms and sites of action of ursodeoxycholic acid in cholestasis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:318–328. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: a randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial. Hepatology. 1999;30:1381–1386. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513–1520. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshikawa M, Tsujii T, Matsumura K, Yamao J, Matsumura Y, Kubo R, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of ursodeoxycholic acid on immune responses. Hepatology. 1992;16:358–364. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishizaki K, Iwaki T, Kinoshita S, Koyama M, Fukunari A, Tanaka H, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid protects concanavalin A-induced mouse liver injury through inhibition of intrahepatic tumor necrosis factor-alpha and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 production. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;578:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maggiore G, Benedetti F, Massa M, Pignatti P, Martini A. Circulating levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in children with autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;20:23–27. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durazzo M, Niro G, Premoli A, Morello E, Rizzotto ER, Gambino R, et al. Type 1 autoimmune hepatitis and adipokines: new markers for activity and disease progression? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:476–482. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherñavsky AC, Paladino N, Rubio AE, Biasio MB, Periolo N, Cuarterolo M, et al. Simultaneous expression of Th1 cytokines and IL-4 confers severe characteristics to type I autoimmune hepatitis in children. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Takagi S, Okamaoto R, Ikeda H, et al. Persistent normalization of serum alanine aminotransferase levels improves the prognosis of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2005;43:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, Okamaoto R, Ikeda H, Makino Y, et al. Persistent elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase levels leads to poor survival and hepatocellular carcinoma development in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1197–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czaja AJ, Freese DK, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479–497. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]