Abstract

The subjective sense of future time plays an essential role in human motivation. Gradually, time left becomes a better predictor than chronological age for a range of cognitive, emotional, and motivational variables. Socioemotional selectivity theory maintains that constraints on time horizons shift motivational priorities in such a way that the regulation of emotional states becomes more important than other types of goals. This motivational shift occurs with age but also appears in other contexts (for example, geographical relocations, illnesses, and war) that limit subjective future time.

Most scientists would agree that the explicit study of time falls in the purview of physics, yet interest in various aspects of time spans the natural and social sciences. Time is an integral part of virtually all psychological phenomena. From the sequencing of rewards involved in operant and classical conditioning to the flow of oxygen in the measurement of brain activation, time is built into most behavioral and psychological processes. Psychological science, however, has focused relatively little on the implications of our ability not only to monitor time but also to appreciate that time eventually runs out. I maintain that the subjective sense of remaining time has profound effects on basic human processes, including motivation, cognition, and emotion.

Although change over time is the basic foundation of developmental psychology, theoretical models of human development focus almost exclusively on the passage of time since birth. In child development, this marker has served scientists well. A substantial literature shows that chronological age is an excellent (albeit imperfect) predictor of cognitive abilities (1, 2), language (3), and sensorimotor coordination (4). At increasingly older ages, however, chronological age is a poorer predictor. Instead, increased heterogeneity or differentiation within samples is considered to be a cardinal feature of life-span development (5). Presumably, this is due primarily to differences in experiences and opportunities that individuals encounter over time. Chronic stress, level of education, close relationships, and social status all place individuals on very different developmental trajectories that affect not only day-to-day functioning but also health and longevity (6). Late in life, chronological age continues to provide a rough marker of accumulated life experience, but it loses the precision it holds in youth.

A second index of time becomes salient as people grow older, namely the subjective sense of remaining time until death. Although correlated with chronological age, this subjective sense of time gradually becomes more important than time since birth. Because goal-directed behavior relies inherently on perceived future time, the perception of time is inextricably linked to goal selection and goal pursuit. Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST), a lifespan theory of motivation, is grounded fundamentally in the human ability to monitor time, to adjust time horizons with increasing age, and to appreciate that time ultimately runs out (7). SST maintains that time horizons play a key role in motivation. Goals, preferences, and even cognitive processes, such as attention and memory, change systematically as time horizons shrink. Because chronological age is correlated with time left in life, systematic associations between age and time horizons appear, but findings from experimental studies show that when time perspective is manipulated or controlled statistically, many age differences disappear. In short, across many dimensions, older and younger people behave remarkably similarly when time horizons are equated.

Events like the attacks on September 11th and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong completely eliminated age differences on some measures of motivation (8). Young men who suffered from HIV before effective treatments were available seemed to view their social world in the same way that very old people do (9). In all of these cases, the fragility of life was acutely primed. The subjective sense of time left was affected and, in turn, equated age differences in preferences and desires.

SST maintains that two broad categories of goals shift in importance as a function of perceived time—those concerning the acquisition of knowledge and those concerning the regulation of emotion states. When time is perceived as open-ended, goals that become most highly prioritized are most likely to be those that are preparatory, focused on gathering information, on experiencing novelty, and on expanding breadth of knowledge. When time is perceived as constrained, the most salient goals will be those that can be realized in the short-term, sometimes in their very pursuit. Under such conditions, goals tend to emphasize feeling states, particularly regulating emotional states to optimize psychological well-being. SST predicts that people of different ages prioritize different types of goals. As people age and increasingly perceive time as finite, they attach less importance to goals that expand their horizons and greater importance to goals from which they derive emotional meaning. Obviously, younger people sometimes pursue goals related to meaning and older people pursue goals related to knowledge acquisition; the relative importance placed on them, however, changes. Indeed, differences between young and old are most striking when goals compete, such as situations in which expanding horizons also entail unpleasant emotional experiences. According to SST, in such cases younger people are far more likely than older people to pursue their goal despite the negative emotional burden. This theoretical shift has helped to make sense of a number of findings in the literature previously referred to as the “paradox of aging” (10). Older people were observed to have smaller social networks, to be drawn less than younger people to novelty, and to reduce their spheres of interest; at the same time, however, they were as happy as (if not happier than) younger people. This makes sense if motivational changes with age lead people to place priority on deepening existing relationships and developing expertise in already satisfying areas of life.

However, according to SST, such differences are not due to “age” but to differences in the perception of future time. There are clear age differences in preferences, and these differences can be eliminated by selectively expanding or constraining time horizons (11, 12). For example, asked to choose among three social partners who represent different types of goals (13), the majority of older people reliably choose emotionally close social partners. Yet when asked to make the choice after imagining that they just received a telephone call from their physician who told them about a new medical advance that virtually ensures they will live far longer than expected, older peoples’ choices resembled those of younger people (12). Similarly, when younger people are asked to imagine that they will soon move to a new geographical location, they “look like” older people: they, too, now choose emotionally close social partners (11). Thus, endings need not be related to old age or impending death. They need simply to limit time horizons. Preferences long thought to reflect intractable effects of biological or psychological aging appear fluid and malleable.

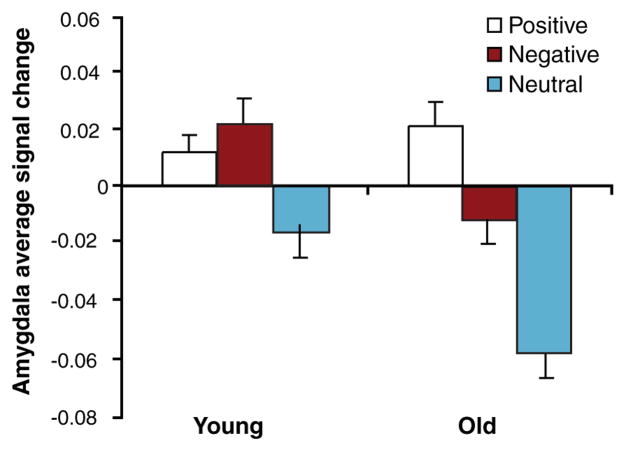

We began to explore the ways in which these different motivational states influence information processing. Helene Fung and I developed pairs of advertisements that were identical except for the featured slogan (14). In one version of the advertisements, the slogans promised to expand horizons. In the other, the slogans promised more emotional rewards (Fig. 1). The majority of older participants preferred the advertisements featuring the emotion-related slogans. They also remembered these slogans and the products associated with them better than they did the slogans about exploration and knowledge. When older participants were asked to imagine an expanded future before they indicated their preference, they made choices similar to those made by younger participants, that is, they failed to show a significant preference for the emotion-related slogans.

Fig. 1.

An example of one pair of advertisements used to study age differences in preferences and memory for products. In each pair, the advertisements were identical except for the slogan. One slogan was related to gaining knowledge. The second promised an emotionally meaningful reward (14).

Recently, research has indicated a special preference for emotionally positive information over emotionally negative information in memory in older adults (15–17). This is particularly intriguing because it has long been known that younger people find negative information more attention-grabbing and memorable than positive information. Indeed, many have posited an evolutionary basis to a preference in memory and attention for negative information. Negative material is richer in information than is positive material, which often soothes instead of arouses. If the value placed on learning new information changes with shrinking time horizons, however, this preference should dissipate across adulthood. Our research team has coined the term the “positivity effect” to describe a developmental pattern that has emerged in which a selective focus on negative stimuli in youth shifts to a relatively stronger focus on positive information in old age (16). Although in some studies, the effect is accounted for primarily by younger people remembering relatively more negative material than positive material, and in other studies the effect is accounted for by older people remembering more positive than negative material, a shift in the ratio of positive to negative across age groups has nevertheless emerged as a reliable finding in the research literature (18, 19).

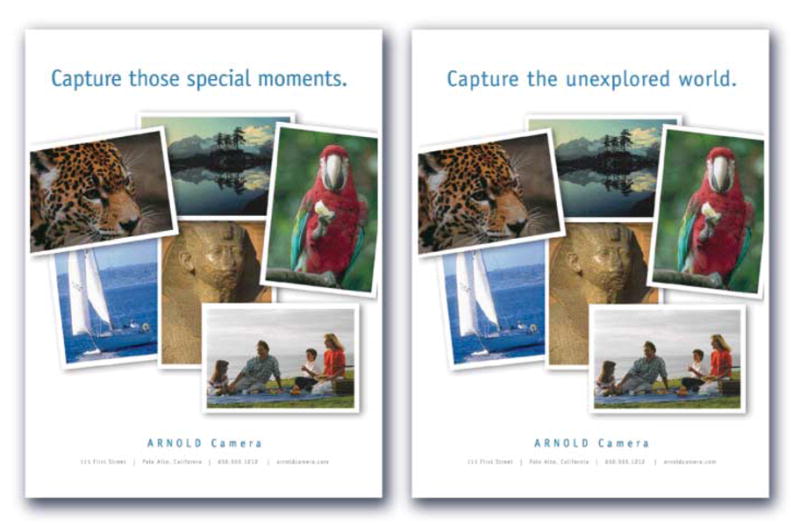

Of particular interest is recent evidence that older people process negative information less deeply than they do positive information (20). While in a brain scanner, older and younger people viewed images of positive, negative, and neutral stimuli. Using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging, activation in the amygdala was measured in response to the different types of images. Consistent with the results of the behavioral studies noted above, whereas younger adults showed heightened amygdala activation in response to both positive and negative images compared with neutral images, amygdala activation in the older adults increased only in response to the positive images (Fig. 2). Thus, not only at recall but at very early stages of processing, older adults diminish encoding of negative material.

Fig. 2.

The percentage of signal change in amygdala activation in response to emotionally positive, emotionally neutral, and emotionally negative images. Younger people show significantly increased activation in response to positive and negative images. Older people show increased activation only in response to positive images (20). [Adapted from Mather et al. (2004)]

SST suggests that many differences between younger and older people that have long been believed to reflect intractable age differences in attitudes or the consequences of age-related decline may be neither. Young or old, when people perceive time as finite, they attach greater importance to finding emotional meaning and satisfaction from life and invest fewer resources into gathering information and expanding horizons. Tests of hypotheses derived from SST have shed light on the literature showing that, although social networks grow smaller, they also grow more satisfying. Older people appear to prefer such social networks. Hypotheses generated by SST have led to discoveries of differential decline in the processing of certain types of information, suggesting that motivation contributes to at least some observed age differences. As illustrated in the study of advertisement preferences described above, understanding these shifts in motivation can help us to frame information for older adults such that it is more memorable. It also may be that special reliance on emotional responses to options will aid decision-making. Of course, a focus on emotionally satisfying stimuli may be a double-edged sword. Preferential attention to positive information, for example, may contribute to susceptibility to scams or other unscrupulous efforts to take advantage of older people. Many questions remain. It appears, however, that consideration of time horizons can offer insights into the ways in which younger and older people differ, but also show that behavioral differences are often driven by the same underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The research program described herein has been generously supported by grant RO18816 from the National Institute on Aging.

References and Notes

- 1.Baltes PB, Mayer KU. The Berlin Aging Study: Aging from 70 to 100. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salthouse TA, Davis HP. Dev Rev. 2006;26:31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke DM, Shafto MA. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13:21. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindenberger U, Marsiske M, Baltes PB. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:417. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baltes PB. Dev Psychol. 1987;23:611. [Google Scholar]

- 6.House J. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carstensen LL, Issacowitz D, Charles ST. Am Psychol. 1999;54:165. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fung HH, Carstensen LL. Soc Cognit. 2006;24:248. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carstensen LL, Fredrickson BL. Health Psychol. 1998;17:494. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunzmann U, Little T, Smith J. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:484. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredrickson BL, Carstensen LL. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:335. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fung HH, Carstensen LL, Lutz A. Psychol Aging. 1999;14:595. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Three prospective social partners are presented: the author of a book you just read, an acquaintance with whom you seem to have much in common, and a member of your immediate family.

- 14.Fung HH, Carstensen LL. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:163. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles ST, Mather MM, Carstensen LL. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2003;132:310. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mather M, Carstensen LL. Trends Cognit Sci. 2005;9:496. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikels JA, Larkin GL, Reuter-Lorenz PA, Carstensen LL. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:542. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlagman S, Schulz J, Kvavilashvili J. Memory. 2006;14:161. doi: 10.1080/09658210544000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger HA, Goren D, Wilson HR. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:40. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mather M, et al. Psychol Sci. 2004;15:259. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]