Abstract

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A (eIF-5A) is a ubiquitous protein found in all eukaryotic cells. The protein is closely associated with cell proliferation in the G1–S stage of the cell cycle. Recent findings show that the eIF-5A proteins are highly expressed in tumor cells and act as a cofactor of the Rev protein in HIV-1-infected cells. The mature eIF is the only protein known to have the unusual amino acid hypusine, a post-translationally modified lysine. The crystal structure of eIF-5A from Methanococcus jannaschii (MJ eIF-5A) has been determined at 1.9 Å and 1.8 Å resolution in two crystal forms by using the multiple isomorphous replacement method and the multiwavelength anomalous diffraction method for the first crystal form and the molecular replacement method for the second crystal form. The structure consists of two folding domains, one of which is similar to the oligonucleotide-binding domain found in the prokaryotic cold shock protein and the translation initiation factor IF1 despite the absence of any significant sequence similarities. The 12 highly conserved amino acid residues found among eIF-5As include the hypusine site and form a long protruding loop at one end of the elongated molecule.

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A (eIF-5A) is a ubiquitous protein found in all eukaryotic cells (1) and archaea (2, 3). The protein was named as such on the basis of early observations of its stimulatory effect on the initiation of protein biosynthesis in cell-free systems of eukaryotic cells (4–6). Although the complete depletion of eIF-5A in yeast did not cause major changes in the rate of protein biosynthesis (7), suggesting that eIF-5A is not absolutely necessary for general protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells, the requirement of eIF-5A for cell proliferation is well established. The depletion of eIF-5A in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) results in enlarged cells arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (7). Yeast mutants with both of their eIF-5A genes knocked out produce nonviable spores (8).

The eIF-5A is the only known protein in eukaryotic cells that contains the unusual amino acid hypusine, Nɛ-(4-amino-2-hydroxybutyl)-l-lysine (1). The hypusine is synthesized via a two-step post-translational modification (1): the 4-aminobutyl moiety of a spermidine molecule is first transferred to the ɛ-amino group of a specific lysine residue by deoxyhypusine synthase (DOHS), then the intermediate deoxyhypusyl residue is hydroxylated by deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (DOHH). The inhibition of deoxyhypusyl hydroxylation in eIF-5A maturation correlates to a dose-dependent inhibition of DNA synthesis in the LAZ463 line of Epstein–Barr-virus-transformed human lymphoblastoid cells (9). Mammalian cells treated with inhibitors of DOHS or DOHH fail to proliferate (10, 11). These observations suggest that hypusine formation in eIF-5A may directly affect the expression of a selective set of genes involved in the G1–S boundary in the eukaryotic cell cycle. The enzymes DOHH and DOHS, which catalyze the maturation of eIF-5A, are regarded as potential targets for intervention in cell over-proliferation (9).

In mammalian cells, eIF-5A is localized in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments and may also play a role in regulating mRNA transport and/or protein translation (12). It was found to be the cofactor of the Rev transactivator protein of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and the Rex protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I). Since Rev/Rex mediates the translocation of viral mRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, it is possible that eIF-5A may interact with a nuclear RNA export system (13, 14).

It has been reported that the expression of eIF-5A is highly correlated to several pathways in human diseases. For example, the expression level of eIF-5A in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells is significantly up-regulated in HIV-1-infected patients compared with uninfected individuals (12). A recent report showed that the hypusine formation activity is serum-responsive and is significantly elevated by more than 30-fold in Ras-oncogene-transfected mouse cells (15). Conversely, human carcinoma cells that have been exposed to a cytostatic concentration of recombinant interferon α2 show a 75% reduction of hypusine synthesis and increased epidermal growth factor receptor expression at the tumor cell surface, which lead to a decreased proliferative index of the tumor cells (16).

Homologs of eIF-5A have been found in archaea, such as Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, Halobacterium cutirubrum, and Thermoplasma acidophilum (2). The gene encoding the eIF-5A homolog in Methanococcus jannaschii was cloned recently by the PCR method (17). The gene product, MJ eIF-5A, has a 31% amino acid sequence identity with human eIF-5A and a 50% identity with the hypusine-containing protein from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (Table 1). The unique lysine modification site flanked by a conserved sequence strongly suggests that a common ancestry exists between this archaeal hypusine-containing protein and the eukaryotic eIF-5A. This possibility is supported by the observation that MJ eIF-5A can be modified by DOHSs from human and yeast (M. H. Park, personal communication). In this paper, we report the crystal structures of MJ eIF-5A in two crystal forms at 1.9 Å and 1.8 Å resolution.

Table 1.

Sequence alignment of selected eIF-5A proteins

| Protein | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 139 | |

| mj_eIF5a | .......... .VIIMPGTKQ VNVGSLKVGQ YVMIDGVPCE IVDISVSKPG |

| s_eIF5a | .......... .MGIQMSIQY TTVGDLKVGS YVMIDGEPCR VVEITKAKTG |

| h_eIF5a | .MADDLDFET GDAGASATFP MQCSALRKNG FVVLKGWPCK IVEMSASKTG |

| y_eIF5a | MSDEEHTFET ADAGSSATYP MQCSALRKNG FVVIKSRPCK IVDMSTSKTG |

| ****** | |

| 4089 | |

| mj_eIF5a | KHGGAKARVV GIGIFEKVKK EFVAPTSSKV EVPIIDRRKG QVLAIMGDMV |

| s_eIF5a | KHGSAKANVV AIGLFTGQKR SLMAPVDQQV EVPIIEKHVG QILADKGDNL |

| h_eIF5a | KHGHAKVHLV GIDIFTGKKY EDICPSTHNM DVPNIRRNDF QLIGIQDGYL |

| y_eIF5a | KHGHAKVHLV AIDIFTGKKL EDLSPSTHNM EVPVVKRNEY QLLDIDDGFL |

| ****** | |

| 90131 | |

| mj_eIF5a | QIMDLQTYET LELPIP.... ..EGIEGLEP GGE..VEYIE AVGQYKITRV |

| s_eIF5a | TIMDLESYET FDLEKPTEN. ..EIVSKIRP GAE..IEYWS VMGRRKIVRV |

| h_eIF5a | SLLQDSGEVP EDLRLPEGDL GHEIEQKYDC GEEILITVLS AMTEEAAVAI |

| y_eIF5a | SLMNMDGDTK DDVKAPEGEL GDSLQTAFDE GKDLMVTIIS AMGEEAAISF |

| 132 | |

| mj_eIF5a | IGGK... |

| s_eIF5a | K...... |

| h_eIF5a | KAMAK.. |

| y_eIF5a | KEAARTD |

mj, M. jannaschii; s, Sulfolobus acidocaldarius; h, human; y, yeast. Asterisks mark highly conserved residues around the hypusine modification site (Lys-40).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization of the MJ eIF-5A Protein.

A gene from M. jannaschii homologous to eIF-5A was cloned by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method, overexpressed in Escherichia coli, and its protein, MJ eIF-5A, was subsequently purified (17). The protein could be modified by the DOHS from yeast and human cells with spermidine as a substrate (M. H. Park, personal communication). Crystallization experiments were conducted by using the sparse matrix screening method (18), and two crystal forms of the protein were obtained by the vapor diffusion method. Crystal form I was grown at room temperature from a solution containing 10 mg/ml protein, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.6, and 8% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000. The space group of these crystals is P4122 and the unit cell dimensions are a = b = 45.52 Å, c = 155.59 Å. They have an appearance of a tetragonal bipyramid with average dimensions of 300 mm × 300 mm × 600 mm. The c-axis of these crystals is along the long axis of the bipyramid. Assuming a molecular mass of 14,636 Da and one molecule per asymmetric unit, the volume to mass ratio (Vm) is 2.76 Å3/Da (19), and the solvent content is 55%. Crystal form II was grown at 4°C from a solution containing 10 mg/ml protein, 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl buffer at pH 8.5, 0.2 M MgCl2, and 30% PEG 4000. These crystals belong to space group C2 and have unit cell dimensions a = 80.49 Å, b = 40.18 Å, c = 48.58 Å, and β = 124.30°. These crystals have the shape of a flat rectangular prism with average dimensions of 50 mm × 300 mm × 500 mm. Selenomethionine (Se-Met)-substituted MJ eIF-5A was also prepared and crystallized in space group P4122 under the same conditions as those for crystal form I of the native protein but using small native crystals as microseeds.

Structure Determination.

Crystal form I was used for the initial structure determination. A 1.9 Å full data set was collected at the Brookhaven National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) beam line X12B at room temperature with 0.95-Å synchrotron radiation. Heavy atom derivative data were also collected at room temperature by using an R-AXIS IIC imaging-plate detector mounted on a Rigaku rotating anode x-ray generator. Two sets of Hg data, one set of Ir data, and one set of Se data were used for the multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) phase calculation (Table 2). Multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data (20) were collected at beamline X4A at the NSLS. The Se-Met crystals were flash-frozen at 100 K in the presence of 8% glycerol as a cryoprotectant. The f′ and f" of the Se were determined from the x-ray absorption spectrum. All collected data sets (Table 3) were processed with denzo and reduced with the scalepack (21).

Table 2.

Data collection and MIR phasing statistics calculated by sharp (22)

| Values

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Native (form I) | Hg1 | Hg2 | Ir | Se-Met | Native (form II) |

| Rmerge, % | 3.9 | 11.3 | 9.1 | 12.3 | 11.2 | 4.5 |

| Dmin, Å | 1.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Completeness, % | 92.3 | 96.1 | 99.4 | 81.0 | 98.7 | 96.7 |

| Riso, % | — | 20.0 | 30.2 | 29.1 | 14.5 | — |

| Rcullis, % | — | 76.0 | 88.0 | 89.0 | 46.0 | — |

| Phasing power | — | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 4.4 | — |

| Overall FOM = 0.65 (for 2.6-Å data set) | ||||||

Hg1 and Hg2 are mercuric acetate and mercuric chloride derivatives, respectively; Ir is K2IrCl6. Rmerge = ΣhklΣi[|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Ii(hkl)]. Riso = Σhkl[∥FPH| − |FP∥/|FP|]. Rcullis = Σh01[∥FPH − FP| − |FH(calc)∥/Σh01|FPH − FP]. Phasing power = rms (|FH|/E), where E = residual lack of closure error. Figure of merit (FOM) = |F(hkl)best|/F(hkl).

Table 3.

Statistics for data collection of the Se-Met crystal of MJ eIF-5A frozen at 100 K at Brookhaven NSLS beamline X4A (20–2.4 Å)

| Wavelength, Å | Unique reflections, no. | Completeness, % | Signal 〈I/σ(I)〉 | Rsym, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9871 (remote) | 11,545 | 99.4 | 14.8 | 6.0 |

| 0.9795 (edge) | 11,571 | 99.2 | 13.9 | 6.3 |

| 0.9793 (peak) | 11,534 | 99.3 | 12.6 | 6.6 |

| 0.9649 (remote) | 11,190 | 96.3 | 8.3 | 9.3 |

Space group P4122; cell a = b = 44.11 Å, c = 155.54 Å. Rsym = (Σhkl,i |Ii − 〈I〉|)/(Σhkl,iIi).

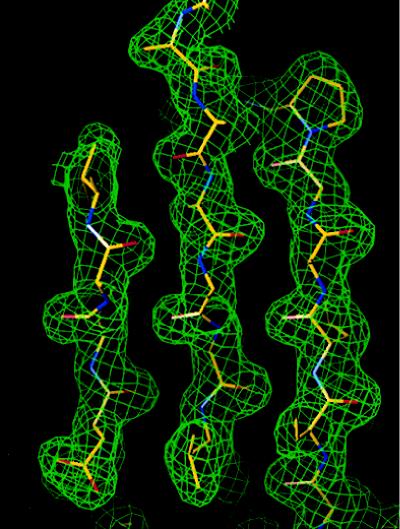

The difference Patterson map between the HgCl2 and the native data set was interpreted and the first heavy atom position was determined. The other heavy atom positions in the other derivatives were identified in the difference Fourier maps by using the phases from HgCl2. The refinement of the heavy-atom parameters and the calculation of the MIR phases to 2.6 Å were performed with the program sharp (ref. 22; Table 2). The initial MIR phases were improved by solvent flipping and extended to 1.9 Å with the program solomon (23). Five selenium sites were identified during the MIR phase calculation. These sites were used to calculate the MAD phases with the program madsys (ref. 19; Table 4), and the electron density was modified with the program dm (24). The quality of the MIR map was excellent, with only two backbone interruptions (Fig. 1). The MAD map generally confirmed the overall fold identified from the MIR maps. The model building was carried out with the program o (25). The positional refinement, simulated annealing refinement, and temperature factor refinement were performed with the program x-plor (26). The SigmaA weighted maps were calculated with the program sigmaa (27). Because of weak electron densities in the N-terminal region (residues 0–3), the loop region around the residue Lys-40 (residues 41–42), and the C-terminal region (residues 134–135), we did not construct models for these regions. A Met was introduced before Val-1 in MJ eIF-5A, and residue number 0 was assigned. During the course of the refinement, 10% of the total reflections were flagged as a test data set and the free R-factor (28) was monitored.

Table 4.

MAD phasing statistics

| Wavelength, Å | 0.9871 Å | 0.9795 Å | 0.9793 Å | 0.9649 Å | Scattering factor

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f′ | f" | |||||

| 0.9871 | 0.044 | 0.060 | 0.050 | 0.068 | −4.34 | 0.51 |

| (0.034) | ||||||

| 0.9795 | 0.063 | 0.048 | 0.083 | −9.08 | 2.75 | |

| (0.037) | ||||||

| 0.9793 | 0.079 | 0.072 | −7.08 | 4.01 | ||

| (0.039) | ||||||

| 0.9649 | 0.084 | −3.08 | 3.75 | |||

| (0.051) | ||||||

| FOM = 0.91; R(°Fa) = 0.47; R(°Ft) = 0.092; 〈Δ(Δφ)〉 = 41.7; 〈σ(Δφ)〉 = 17.5 | ||||||

Table values represent 〈Δ|F|2〉1/2, where Δ|F| is the absolute value of the Bijvoet difference at one wavelength (diagonal elements) or the dispersive differences between two wavelengths (off-diagonal element). The values for centric Bijvoet reflections, which would be equal to zero for perfect data and serve as an estimate of the noise in the anomalous signals, are shown in parentheses. The listed scattering factors f′ and f" are the refined values for selenium atoms in the crystal of MJ eIF-5A. R = Σhkl[Σi∥Fi| − 〈F〉∥/Σhkl|F|. °Ft is the contribution to the structure factor by normal scattering from all atoms. °Fa is the contribution to the structure factor from the anomalously scattering atoms. Superscript ° indicates the wavelength-independent value. Δ(Δφ) is the difference between two independent determinations of Δφ, which is the phase difference between °Ft and °Fa.

Figure 1.

Typical regions of the solvent-flattened experimental electron density map.

The crystal structure of crystal form II was determined by the molecular replacement method with the program AMoRe (29), using the model of crystal form I as a probe. The rigid body refinement was performed with x-plor for the solution of the molecular replacement. Refinement steps carried out were similar to those for crystal form I. The model of crystal form II contains 133 residues from 0 to 132. A poly(Ala) model was built in the first five residues of the N terminus. Structural evaluation with the program procheck (30) indicates that the refined structure has good geometric parameters. All backbone dihedral angles fall within allowed regions in a Ramachandran plot. Table 5 lists the current status of the refinement of both crystal forms.

Table 5.

Refinement statistics of both crystal forms

| Data | Crystal form I (P4122) | Crystal form II (C2) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of non-hydrogen atoms | 965 | 992 |

| No. of water molecules | 96 | 109 |

| Final crystallographic parameters | ||

| Resolution range, Å | 6.0–1.9 | 20.0–1.8 |

| No. of reflections, (|F| > 2σ) | 11,639 | 11,482 |

| R-factors, % | 20.5 | 21.9 |

| Free R-factors, % | 28.9 | 26.1 |

| 〈B〉, Å2 | ||

| All atoms | 45.0 | 25.5 |

| All protein atoms | 43.1 | 24.9 |

| Protein backbone atoms | 40.7 | 23.5 |

| Protein side-chain atoms | 45.9 | 26.5 |

| Water atoms | 63.6 | 31.4 |

| rms deviations from ideal geometry | ||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.012 | 0.011 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.55 | 1.68 |

R-factor = 100 × Σhkl∥Fo(hkl)| − |Fc(hkl)∥/Σhkl|Fo(hkl)|. Free R-factor (Rfree) = Σhkl∥Fo(hkl, test)| − |Fc(hkl, test))∥/Σhkl|Fo(hkl, test))|.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall Structure.

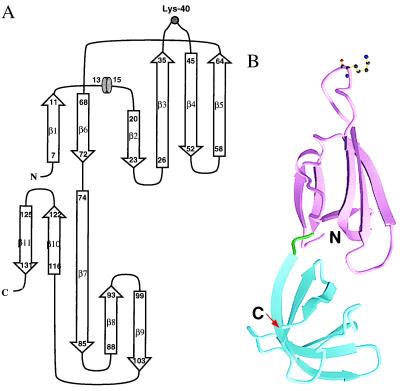

The crystal structure of MJ eIF-5A comprises two distinct antiparallel β-sheet domains arranged in an elongated fashion approximately 63 Å long and 26 Å wide. There are a total of 11 β-strands and a one-turn 310 helix (Fig. 2A). Domain I in crystal form II (residues 0–73) contains strands β1–β6 and the helix. Domain II (residues 74–132), which is slightly smaller than domain I, contains strands β7–β11. The ribbon diagram of the structure is shown in Fig. 2B.

Figure 2.

(A) Topology diagram of the MJ eIF-5A structure. The arrows represent β-strands and the short cylinder represents a 310 helix. The lysine modification site is represented by a gray circle. (B) Ribbon diagram of MJ eIF-5A structure in C2 crystal form. The arrows represent β-strands. The secondary structures were assigned by the method of Kabsch and Sander (31). Two domains are colored magenta and blue and connected by a green linker. The side chain of Lys-40 is shown as a ball-and-stick model. This figure was made with molscript (32).

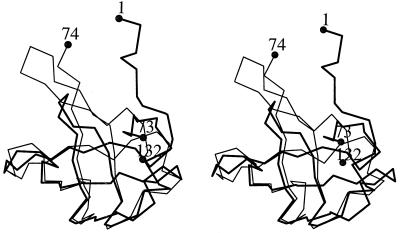

Domain I folds as a semi-open β-barrel in which strands β2, β3, β4, and β5 form an antiparallel open β-sheet covered by a smaller antiparallel β-sheet formed by β1 and β6. Strand β3 has a rather large twist such that the directions of its beginning and end differ by about 90°. Between strands β1 and β2 there is a one-turn helix that covers the open side of the β-barrel. The hypusine-modification site is located between strands β3 and β4, extending into a long, protruding loop. Domain II resembles the oligonucleotide-binding fold (OB fold) (33) found in the structures of several proteins such as Escherichia coli cold shock protein (34), prokaryotic translation initiation factor IF1 (35), staphylococcal nuclease (36), and the N-terminal domain of yeast Asp-tRNA synthetase (37). Strands β7, β8, and β9 form one antiparallel β-sheet which forms a sandwich with another antiparallel β-sheet formed by β10, β11, and β7. The secondary structure assignments of the residues are shown in Fig. 2A. Domains I and II have a similar β-barrel fold and can be overlapped with a 1.2 Å root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) from 31 Cα atoms (Fig. 3). However, the topology connecting the two β-sheets in one domain is different from that of the other (Fig. 3).

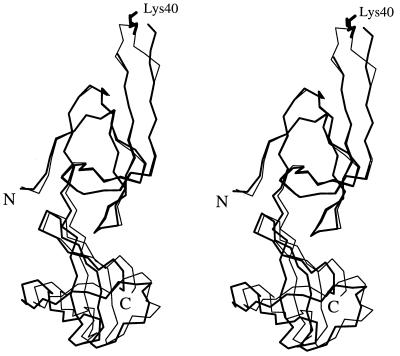

Figure 3.

The α-carbon traces of domain I (thick line, residues 1–73) are overlapped with those of domain II (thin line, residues 74–132) in a stereo diagram. The β-strands β3, β4, and β5 of domain I are superimposed on β7, β8, and β9 of domain II, respectively. The first and the last residues in each domain are labeled.

MJ eIF-5A crystallizes in two crystal forms. Crystal form I belongs to space group P4122, and form II to C2. In both crystals, residues 34–45, the highly conserved 12 residues containing the hypusine modification site (Lys-40), are located in a long protruding loop connecting β3 and β4. The conserved Lys-40 and His-41 are at the tip of this loop, which is located at the end of the elongated shape of the structure, and are fully exposed to solvent in both crystal forms. Residues His-41 and Gly-42 are disordered in crystal form I but are ordered in crystal form II. In crystal form II, this long loop is stabilized by the intramolecular backbone hydrogen bond between residues 39 and 43, and the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the carbonyl atoms of residues 38 and 39 and the amide group of Gln-96 from a symmetry-related molecule.

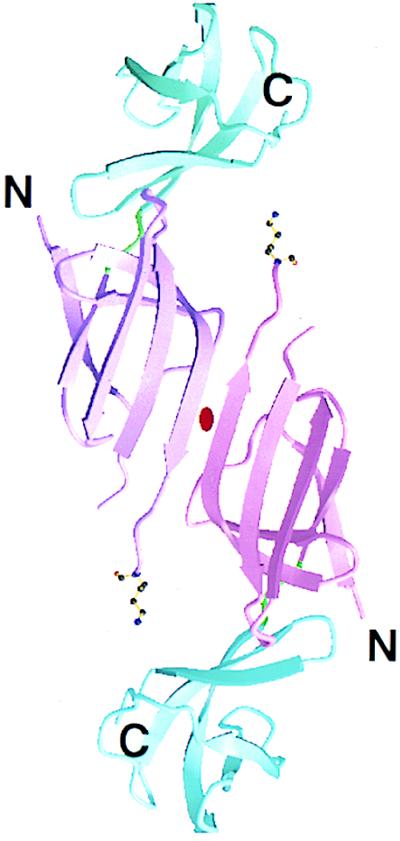

In crystal form I, two of the molecules related by a crystallographic twofold rotation axis form a dimer connected by intermolecular hydrogen-bond interactions. The β3 strand of the domain I of one molecule interacts with the same strand of the twofold-related molecule by six interbackbone hydrogen bonds. These hydrogen bonds link the domain I of the two molecules side by side, forming a continuous six-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 4). However, the crystal contacts in crystal form II are predominantly van der Waals contacts and side-chain interactions. No dimer-like interaction is found in crystal form II.

Figure 4.

Ribbon diagram showing the twofold dimer present in the P4122 crystal form (crystal form I). The arrows represent β-strands. The side chain of Lys-40 is shown as a ball-and-stick model. Two domains are colored magenta and blue with different shadings for each subunit. The two-fold symmetry axis is marked in the center of the dimer.

Two Domains with a Flexible Hinge.

The tertiary structures of the two crystal forms of MJ eIF-5A are very similar except for the interdomain orientation. When domain I of crystal form II is superimposed onto that of crystal form I, domain II does not overlap well (Fig. 5). The rmsd of the coordinates for all of the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O) between the two crystal forms is 1.2 Å. However, when superimposed separately, the backbone rmsd for domain I alone is 0.5 Å and for domain II is 0.9 Å. The two domain IIs can be brought together by the rotation of one domain approximately 7° about the axis along the length of the molecule, suggesting that the two domains are connected by a flexible hinge. This structure agrees with the fact that the average atomic temperature factor (B) of domain II is approximately 50% higher than that of domain I in both crystal forms (Table 6).

Figure 5.

Stereo diagram of superimposed α-carbon traces of MJ eIF-5A structure in crystal form I (thick line) and those in crystal form II (thin line). The superposition is based on residues 5–73 of domain I.

Table 6.

Comparison of average B-factors of domain I and II in the two crystal forms

| Crystal form | Atoms |

B-factor, Å2

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain I | Domain II | ||

| I | Backbone | 33.0 | 49.4 |

| Sidechain | 39.1 | 52.8 | |

| II | Backbone | 21.9 | 25.4 |

| Sidechain | 24.0 | 29.0 | |

Biological Implications.

The conformation of the 12 conserved residues containing the hypusine modification site of the eIF-5A is of critical importance for hypusine formation. Enzymology studies showed that the unmodified recombinant human eIF-5A and MJ eIF-5A are good substrates of human DOHS (M. H. Park, personal communication). However, neither the free lysine, nor the synthetic 9- or 16-mer peptides surrounding the modification site of the human eIF-5A, nor a mutant protein (Lys-50 mutated to Arg) of the human eIF-5A functioned as substrate for human DOHS (1), suggesting that the conformation of this region is important for the modification reaction. The structural features of MJ eIF-5A strongly suggest that it binds to nucleic acid because spermidine, a precursor of hypusine in domain I, is known to bind to tRNA (38) and domain II has the oligonucleotide-binding fold.

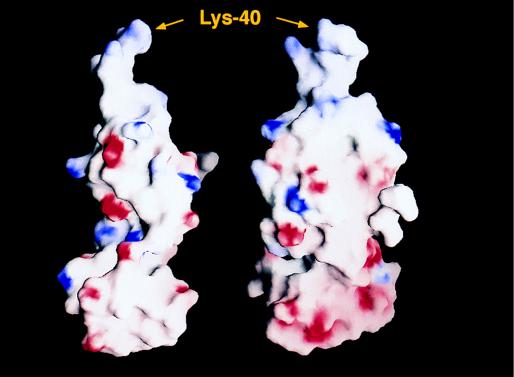

The surface charge distribution of MJ eIF-5A is very distinctive. Domain I contains six acidic amino acid residues and 11 basic residues. Five of the basic residues are located in the 12 conserved residues surrounding Lys-40, which is subject to modification. Conversely, domain II has 11 acidic and five basic residues. No basic residue was found in residues 80–126, the core of domain II. Consequently, the three-dimensional structure of MJ eIF-5A is highly polar as shown in Fig. 6. The polarization of the charge distribution and the flexibility of the interdomain hinge described above may play important roles in the protein–protein and protein–RNA interactions. These properties may be implicated in the function of eIF-5A as a cofactor of the Rev/Rex proteins of HIV-1/HTLV-I (13, 14) and as a translation initiation factor selective for a particular subset of mRNAs encoding proteins that are critical for the initiation of DNA replication (1).

Figure 6.

Two different views of the surface charge distribution of MJ eIF-5A as calculated by program grasp (39). The red and blue colors represent negatively and positively charged surfaces, respectively. The lysine modification site (Lys-40) is labeled.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Myung Hee Park of the National Institutes of Health for her helpful discussions and the hypusine modification assays for MJ eIF-5A. We thank Drs. Craig Ogata at X4A and Malcolm Capel at X12B at the Brookhaven NSLS. This work has been supported by the Director, Office of Energy Research, Office of Bioscience and Environmental Research, of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract DE-AC03-76SF00098 (R.K. and S.-H.K.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- eIF

eukaryotic translation initiation factor

- MJ

Methanococcus jannaschii

- DOHS

deoxyhypusine synthase

- MIR

multiple isomorphous replacement

- MAD

multiwavelength anomalous diffraction

- Se-Met

selenomethionine

- NSLS

National Synchrotron Light Source

- rmsd

rms deviation

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Biology Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973 (PDB ID code 1eif for crystal form I and 2eif for crystal form II).

References

- 1.Park M H, Wolff E C, Folk J E. Biofactors. 1993;4:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumann H, Klink F. System Appl Microbiol. 1989;11:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartig D, Lemkemeier K, Frank J, Lottspeich F, Klink F. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:751–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemper W M, Berry K W, Merrick W C. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:5551–5557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benne R, Brown-Luedi M L, Hershey J W. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:3070–3077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merrick W C. Methods Enzymol. 1979;60:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(79)60010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H A, Hershey J W B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3934–3940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnier J, Schwelberger H G, Smit-Mcbride Z, Kang H A, Hershey J W B. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3105–3114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanauske-Abel H M, Park M H, Hanauske A R, Popowicz A M, Lalande M, Folk J E. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1221:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park M H, Wolff E C, Lee Y B, Folk J E. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27827–27832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y B, Park M H, Folk J E. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3053–3061. doi: 10.1021/jm00016a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bevec D, Klier H, Holter W, Tschachler E, Valent P, Lottspeich F, Baumruker T, Hauber J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10829–10833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruhl M, Himmelspach M, Bahr G M, Hammerschmid F, Jaksche H, Wolff B, Aschauer H, Farrington G K, Probst H, Bevec D. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1309–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katahira J, Ishizaki T, Sakai H, Adachi A, Yamamoto K, Shida H. J Virol. 1995;69:3125–3133. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3125-3133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z P, Chen K Y. Cancer Lett. 1997;115:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caraglia M, Passeggio A, Beninati S, Leardi A, Nicolini L, Improta S, Pinto A, Bianco A R, Tagliaferri P, Abbruzzese A. Biochem J. 1997;324:737–741. doi: 10.1042/bj3240737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim K K, Yokota H, Kim R, Kim S-H. Protein Sci. 1997;10:2268–2270. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jancarik J, Kim S-H. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:409–411. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews B W. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendrickson W A. Science. 1991;254:51–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1925561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otwinowski Z. In: Data Collection and Processing. Sawyer L, Isaacs N, Bailey S, editors. Warrington, U.K.: SERC Daresbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de la Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrahams J P, Leslie A G W. Acta Crystallogr D. 1996;52:30–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995008754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowtan K D. Acta Crystallogr D. 1993;49:148–157. doi: 10.1107/S0907444992007698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones T A, Zou J-Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunger A T. x-plor, A System for X-ray Crystallography and NMR. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press; 1993. , Version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Read R J, Schierbeek A J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1988;21:490–495. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunger A T. Nature (London) 1992;355:472–474. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thronton J M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabsch W, Sander C. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murzin A G. EMBO J. 1993;12:861–867. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindelin H, Jiang W, Inouye M, Heinemann U. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5119–5123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sette M, van Tilborg P, Spurio R, Kaptein R, Paci M O, Gualerzi C O, Boelens R. EMBO J. 1997;16:1436–1443. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hynes T R, Fox R O. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;10:92–105. doi: 10.1002/prot.340100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavarelli J, Rees B, Ruff M, Thierry J-C, Moras D. Nature (London) 1993;362:181–184. doi: 10.1038/362181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pochon F, Cohen S S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;47:720–726. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90551-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholls A, Sharp K A, Honig B. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]