Abstract

Vertebrate forms of the molybdenum-containing enzyme sulfite oxidase possess a b-type cytochrome prosthetic group that accepts reducing equivalents from the molybdenum center and passes them on to cytochrome c. The plant form of the enzyme, on the other hand, lacks a prosthetic group other than its molybdenum center and utilizes molecular oxygen as the physiological oxidant. Hydrogen peroxide is the ultimate product of the reaction. Here, we present data demonstrating that superoxide is produced essentially quantitatively both in the course of the reaction of reduced enzyme with O2 and during steady-state turnover and only subsequently decays (presumably noncatalytically) to form hydrogen peroxide. Rapid-reaction kinetic studies directly following the reoxidation of reduced enzyme demonstrate a linear dependence of the rate constant for the reaction on [O2] with a second-order rate constant of kox = 8.7 × 104 ± 0.5 × 104 m−1s−1. When the reaction is carried out in the presence of cytochrome c to follow superoxide generation, biphasic time courses are observed, indicating that a first equivalent of superoxide is generated in the oxidation of the fully reduced Mo(IV) state of the enzyme to Mo(V), followed by a slower oxidation of the Mo(V) state to Mo(VI). The physiological implications of plant sulfite oxidase as a copious generator of superoxide are discussed.

Introduction

Molybdenum-containing enzymes are found in most organisms and (with the notable exception of nitrogenase) fall into three families, as epitomized by xanthine oxidase, dimethyl sulfoxide reductase, and sulfite oxidase. The sulfite oxidase family consists of vertebrate sulfite oxidases, plant sulfite oxidases, bacterial sulfite dehydrogenase, and assimilatory nitrate reductases (1). Each of these enzymes catalyzes oxygen atom transfer to (or from) a substrate lone pair of electrons.

In vertebrates, sulfite oxidase catalyzes the final step in the metabolism of sulfur derived from compounds such as the amino acids methionine and cysteine, as well as the sulfatides and related components of the myelin sheath and other cellular membranes (2–4). Its action ensures that intracellular levels of the otherwise deleterious sulfite ion remain at acceptably low levels. The plant form of sulfite oxidase not only plays a role in sulfite detoxification, but it also serves as an intermediate enzyme in the assimilatory reduction of sulfate (5). Sulfite dehydrogenase is the bacterial equivalent of sulfite oxidase, oxidizing sulfite to sulfate in the course of chemolithotrophic growth with thiosulfate as an energy source (6). Despite the various physiological roles of these enzymes, they all catalyze the same overall reaction.

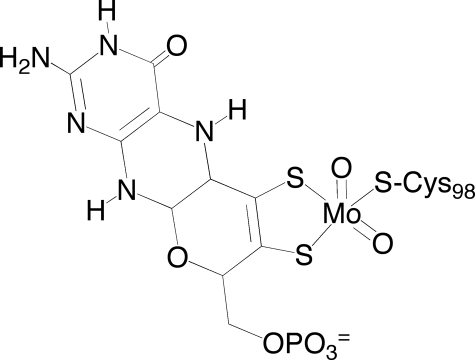

All three enzymes possess a molybdenum center with the metal in a square-pyramidal LMoVIO2(S-Cys) geometry, where L represents a pyranopterin cofactor (common to all mononuclear molybdenum and tungsten enzymes) coordinated to the metal through a dithiolene bond (Fig. 1) (7). The molybdenum-binding portions of all three types of sulfite-oxidizing enzymes exhibit a high degree of sequence identity and structural homology (8).

FIGURE 1.

Molybdenum center of plant sulfite oxidase. The pterin cofactor is coordinated to the metal via its enedithiolate side chain. The remainder of the coordination sphere is taken up by a pair of terminal Mo = O ligands and the thiolate of Cys98.

The similarity in the reaction mechanisms with sulfite (i.e. the reductive half-reaction of the catalytic cycle) notwithstanding, these sulfite-oxidizing enzymes differ substantively with regard to the substrate used in the oxidative half of the catalytic sequence. Both vertebrate sulfite oxidases and bacterial sulfite dehydrogenases possess heme prosthetic groups (b5- and c552-like, respectively) which accept electrons from the molybdenum centers in the course of catalysis and eventually pass them on to cytochrome c and the respiratory chain and the electron transport chain of the organism (9–11). The vertebrate forms of sulfite oxidase are α2 dimers, with the heme domain only loosely tethered to the molybdenum domain via a flexible 10- amino acid linker. The bacterial sulfite dehydrogenases are αβ dimers, with separate heme and molybdenum subunits bound in a more stable, yet noncovalent, interaction (10).

The amino acid sequence and subsequent crystal structure of plant sulfite oxidase have revealed that it lacks any redox-active center other than its molybdenum center (8, 12). Further, plant sulfite oxidase does not react directly with cytochrome c at any appreciable rate (5, 13). Instead, it utilizes molecular oxygen as oxidant, ultimately resulting in the formation of hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2) (5, 8, 14). Recent in vitro work has suggested that plant sulfite oxidase is involved in a sulfite regulatory pathway in peroxisomes, in which increased levels of sulfite lead to inhibition of peroxisomal catalases, resulting in an increase in the hydrogen peroxide concentration that subsequently nonenzymatically oxidizes sulfite (5, 14, 15). Still, mutations in plant sulfite oxidase resulting in loss of activity are not lethal, whereas mutations in their vertebrate counterparts are (5).

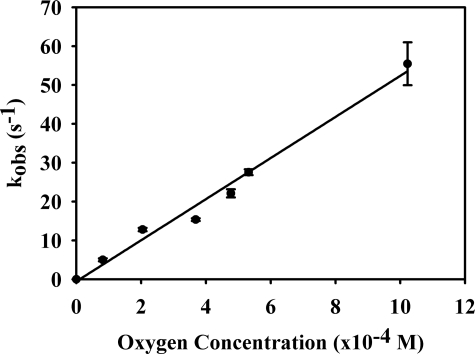

FIGURE 2.

Dependence of observed rate constant versus [O2] for the reoxidation of plant sulfite oxidase. The observed linear dependence yields a slope with kox = 5.3 ± 0.3 × 104 m−1s−1, with a zero y axis intercept. The data points are the average of at least three transients with error bars shown for each point. The reaction was performed in Tris acetate buffer, pH 8.0, at 4 °C.

To gain a better understanding of plant sulfite oxidase, we have examined its oxidative half-reaction in some detail. Here, we present results demonstrating effectively quantitative generation of superoxide by plant sulfite oxidase, both in the reaction of reduced enzyme with O2 and during steady-state turnover. We further demonstrate explicitly that reoxidation of the fully reduced Mo(IV) state of the enzyme occurs in two sequential one-electron steps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzyme Preparation

Recombinant sulfite oxidase from Arabidopsis thaliana was purified by a modification of the procedure described by Eilers et al. (8) and Hemann et al. (13). Escherichia coli cells (strain TP1000, ΔmobAB, possessing the pQE80-At-sox plasmid) (8, 16) were grown aerobically, at 37 °C, overnight and then diluted 1:50 into a modified 2× YT medium (16 g of tryptone, 10 g of yeast extract, 5 g of sodium chloride/liter) that was supplemented with 1.0–1.5 mm molybdic acid and 0.1 mm isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside. Cultures were grown at 30 °C for 24 h and the cells harvested by centrifugation. The cells were then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, 30 mm sodium chloride, 10 mm imidazole, pH 8.0) and lysed using a French pressure cell (Thermo Fisher). The lysate was loaded onto a Qiagen nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column and washed with several bed volumes of wash buffer (lysis buffer with 20 mm imidazole). The protein was then eluted from the column with elution buffer (lysis buffer with 100 mm imidazole) and concentrated to ∼1.0 ml. The protein was next loaded onto a Q-Sepharose column that had been preequilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The column was washed with the equilibration buffer, and the eluate containing the holoform of plant sulfite oxidase was collected. The apoprotein (plant sulfite oxidase lacking the molybdenum cofactor) was retained on the column and was subsequently eluted with the same buffer containing 500 mm sodium chloride. The holosulfite oxidase was concentrated to a volume less than 1.0 ml and passed through a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-OAc, pH 8.0, with 5 mm EDTA). The enzyme was concentrated once more, and its concentration was determined using an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 69.8 mm−1cm−1 (8).

Oxidative Half-reaction Studies

Rapid kinetic experiments were performed in 20 mm Tris-OAc buffer, pH 8.0. Plant sulfite oxidase (∼20 μm) was placed in a tonometer fitted with a side arm cuvette, made anaerobic by repeated cycles of evacuation and flushing with argon gas and reduced by titration with a ∼1 mm sodium sulfite solution using a fitted Hamilton titration syringe. The change in absorbance associated with reduction was monitored using a Hewlett-Packard 8452A UV-visible spectrophotometer. Rapid-reaction kinetic experiments were performed with an Applied Photophysics SX-18MV stopped-flow instrument equipped with a diode array detector. The anaerobic, reduced enzyme was loaded into the system and allowed to equilibrate to a temperature 4 °C. Oxygenated buffers were prepared by bubbling pure oxygen through buffer on ice for 2 h to yield a saturated oxygen solution of 2.05 mm. Anaerobic buffer was mixed with oxygen-saturated buffer using a gas-tight Hamilton syringe to yield solutions of known oxygen concentration from 4 μm to 2.05 mm. The spectral changes at 360 and 480 nm were used to follow the reoxidation of enzyme, with rate constants obtained by fitting the transients with manufacturer-supplied software (the ProData Viewer package). This experiment was performed multiple times with at least three transients obtained at each oxygen concentration. The rate constants from each transient were determined, and the average values, which correspond to the observed pseudo first-order rates, kobs, were plotted against the oxygen concentration to obtain the second-order rate constant, kox.

Additional rapid reaction studies were performed in the presence of cytochrome c to follow superoxide generation explicitly. These studies were performed by combining 1.5 μm plant sulfite oxidase (made anaerobic and reduced as described above) with oxidized cytochrome c (∼38 μm) in an aerobic solution of 82, 205, and 532 μm O2. The reduction of cytochrome c by enzyme-generated superoxide was followed by monitoring the increase of absorbance at 550 nm using an effective extinction coefficient of Δϵ = 19.8 mm−1cm−1, which was calculated by dividing the published value of Δϵ = 21.0 mm−1cm−1 (17) by the correction factor of 1.058 to account for the spectral resolution of our machine. This factor was determined empirically from a comparison of the absorbance at 550 nm of a fully reduced sample of cytochrome c in a Cary 500 spectrophotometer at a 0.04 nm spectral resolution to the absorbance of the same sample in our HP8452A spectrophotometer (with a nominal resolution of 2.0 nm). The rate constants were again determined by plotting the absorbance change against time and fitting with a double exponential equation. As a control, this reaction was also performed in the presence of superoxide dismutase (200 units/ml) to determine the extent of any spectral change that was not dependent on superoxide. At least three transients from each of two separate experiments were used to determine the average value as reported.

Oxygraph Studies

Steady-state experiments following O2 consumption directly were performed using a Hansatech Oxygraph system (18) with data analysis performed using the manufacturer's software. All experiments were performed at 4 °C under aerobic conditions with a stir bar spinning at 100 rpm. Sodium sulfite (1.0 mm in 20 mm Tris-OAc, pH 8.0) was added to the reaction chamber, and the chamber volume was adjusted so that no air bubble remained. The solution was allowed to equilibrate to 4 °C, at which point enzyme was added (60 nm final concentration) to start the reaction. Superoxide dismutase was subsequently added to final concentration of 200 units/ml, this having been empirically determined to be sufficient to ensure quantitative scavenging of superoxide. A unit here is defined as the amount of superoxide dismutase required to inhibit the reduction of cytochrome c by 50% in the reaction of xanthine oxidase with xanthine, as described by McCord and Fridovich (19). The initial rate of oxygen consumption was recorded for each reaction, and a plot of the decrease in rate of oxygen consumption versus superoxide dismutase concentration was made.

In separate experiments, in addition to sulfite, superoxide dismutase and cytochrome c were added as appropriate to final concentrations of 200 units/ml and 94.5 μm, respectively. Reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme at a final concentration of 60 nm or 1.6 μm (initial experiments only; data not shown). To determine the amount of superoxide generated, the following reactions were performed: (i) enzyme and substrate only; (ii) enzyme and substrate with superoxide dismutase; and (iii) enzyme with substrate and cytochrome c. Initial rates were determined from the initial slopes of the observed time courses. Initial and final oxygen concentrations were also recorded. For each reaction, at least three repetitions were performed and the values averaged. These experiments were also performed multiple times to check the reproducibility of the data.

As a control, experiments were performed with xanthine oxidase, a known producer of superoxide, using xanthine as substrate (data not shown). The reaction conditions for these experiments were: 7.8 nm functional xanthine oxidase, 100 μm xanthine, 0.1 m pyrophosphate buffer, pH 8.5, 4 °C. Upon addition of cytochrome c, there is a decrease in the rate of oxygen consumption of 32.0%; in the presence of superoxide, the rate decreased by 10.8%. These results indicate that some 22% of the O2 used by xanthine oxidase is reduced to superoxide, in good agreement with previously published values of 22–30% superoxide production under our reaction conditions (20, 21).

Steady-state Cytochrome c Reduction Studies

Steady-state kinetic experiments following cytochrome c reduction by superoxide were performed using a Hewlett-Packard 8452A UV-visible spectrophotometer. Experiments were performed at 4 °C under aerobic conditions in 20 mm Tris-OAc buffer, pH 8.0. Enzyme was added (final concentration of 20 nm) along with cytochrome c (final concentration ∼20 μm) and sulfite (1.0 mm). Initial rates were determined by following the absorbance change/unit of time in the initial, linear phase of the reaction. The total amount of reduced cytochrome c was also determined from the total absorbance change for the reaction, using an empirically determined effective extinction change for the cytochrome used of Δϵ = 19.8 mm−1cm−1. This same reaction was performed in the presence of superoxide dismutase (200 units/ml) to correct for any nonsuperoxide-dependent spectral changes, and the initial rates were observed as before. As stated previously, for the oxygraph data, all data presented are the average of at least three trials, and the experiments were repeated several times for accuracy and reproducibility. As described previously for the oxygraph studies, controls were performed using xanthine oxidase in reaction with xanthine. Rates of cytochrome c reduction were seen, indicating 28% superoxide production. Addition of superoxide dismutase to the system abolished all cytochrome reduction (data not shown). Additional controls were performed to establish that sulfite did not directly reduce cytochrome c under the present reaction conditions and similarly, that hydrogen peroxide at the concentrations ultimately generated by dismutation of superoxide did not reoxidize cytochrome c. Less than 1% of cytochrome c became reduced by sulfite over a long time scale, indicating that a negligible amount of cytochrome c is reduced by sulfite on the short time scale of our experiments (data not shown). Also, the addition of catalase to the reaction mixtures had no effect on the results, indicating that hydrogen peroxide was not reoxidizing cytochrome c to any appreciable degree under our reaction conditions (data not shown).

Other experiments were performed in such a way that allowed the observation of both the reduction of cytochrome c by superoxide and the effect of superoxide dismutase in the course of a single transient a single transient. This was achieved by setting up a stirrer in the spectrophotometer so that the reactants could be added directly to the reaction mix without removing the cuvette from the light path. The reaction was started first by adding sulfite to the desired concentration. Next, cytochrome c was added followed by the enzyme in 10–20-s intervals. Finally, superoxide dismutase was added and data collected for another 10–20 s.

Additional steady-state kinetic studies were performed to determine the effects of pH and temperature on superoxide production in plant sulfite oxidase. Reaction conditions were the same as for the above mentioned oxygraph experiments. The pH range studied was from 6.0 to 10.0 and consisted of the buffers BisTris,2 pH 6.0, BisTris-propane, pH 7.0, Tris, pH 8.0, and glycine, pH 9.0 and 10.0. All buffers were at a concentration of 20 mm. Temperature dependence of the reaction was monitored over the range of 4–30 °C. We saw no apparent temperature or pH dependence for the degree of superoxide production, with all results indicating at least 95% superoxide production (data not shown).

RESULTS

Reaction of Reduced Plant Sulfite Oxidase with O2

Rapid-reaction kinetic studies were performed to determine the rate constants for the oxidative half-reaction of plant sulfite oxidase. After titration of the enzyme to its reduced form under anaerobic conditions with sulfite, it was mixed with buffers of various oxygen concentrations. Enzyme reoxidation was followed by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 360 and 480 nm, which correspond to the enedithiolate-to-molybdenum charge transfer and the cysteinethiol-to-molybdenum charge transfer, respectively (22). A plot of kobs versus [O2] gave a straight line passing through the origin, with a slope reflecting a second-order rate constant of 5.3 ± 0.3 × 104 m−1s−1 (Fig. 2). This result indicates that there is no formation of an Ered ·O2 Michaelis complex prior to oxidation of enzyme and also that the reaction is irreversible (as expected, given the strong thermodynamic favorability of the reaction).

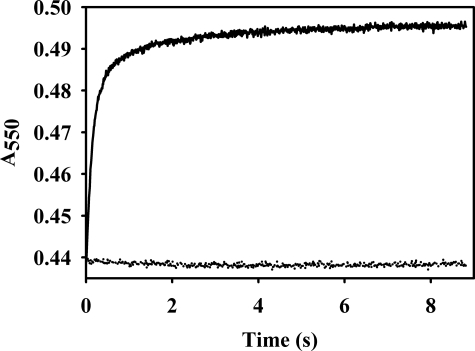

To determine whether superoxide is generated in the course of enzyme reoxidation, this experiment was repeated in the presence ferricytochrome c ± superoxide dismutase. Biphasic transients were seen for the reaction of reduced enzyme with 532 μm O2 (Fig. 3, upper transient), with a fast phase occurring with a rate constant of 47.7 ± 0.4 s−1 followed by a slower phase with one of 7.5 ± 0.1 s−1 (Fig. 3, upper transient). Addition of superoxide dismutase abolished cytochrome c reduction, indicating that all reduction is due to superoxide production (Fig. 3, lower transient). The total absorbance change seen at 550 nm in this experiment was 0.056 and split evenly between the faster and slower kinetic phases (0.029 and 0.027, respectively). This reflects the reduction of ∼2.82 μm cytochrome c, and given the enzyme concentration of 1.5 μm it indicates that 1.0 equivalent of superoxide is generated in each of the two kinetic phases seen in the cytochrome c reduction experiment. This implies a faster reoxidation of Mo(IV) to Mo(V), followed by a slower reoxidation Mo(V) to Mo(VI), with each step yielding 1 equivalent of superoxide.

FIGURE 3.

Reduction of cytochrome c in the course of the oxidative half-reaction of plant sulfite oxidase. Reduction of cytochrome c was monitored via stopped flow, following the absorbance change at 550 nm. Representative transients for each reaction are shown. Upper trace, the reaction of 1.5 μm plant sulfite oxidase with 532 μm O2 in the presence of 38 μm cytochrome c. The transients were best fit as biphasic reactions with a faster rate constant of 47.7 ± 0.4 s−1 and a slower rate constant of 7.5 ± 0.1 s−1. Kinetic values reported are the average obtained from at least three transients. This plot was biphasic with an R2 value of 0.9975. Lower trace, the same reaction in the presence of 200 units/ml superoxide dismutase, demonstrating that there is no reduction of cytochrome c in the absence of superoxide. The reaction was carried out in Tris acetate buffer, pH 8.0, at 4 °C.

These rates may be compared with the observed rate of 27.7 ± 0.8 s−1 at 4 °C, following enzyme reoxidation directly (Fig. 2). Although initial single exponential fits to these data were very good, closer examination of the transients at 360 nm suggested that a double exponential equation provided a somewhat better fit to the data. The phases were not well resolved, however, presumably due to insufficient spectral resolution of the presumed Mo(V) intermediate from the Mo(VI) and Mo(IV) of the enzyme. Attempts to resolve the absorption spectrum of a Mo(V) species were not further pursued here.

Effect of Superoxide Dismutase on Steady-state Consumption of O2

To confirm that superoxide was being produced at significant levels by plant sulfite oxidase with O2, the effect of superoxide dismutase and cytochrome c on O2 consumption by the enzyme was examined in oxygraph experiments. Superoxide dismutase catalyzes the dismutation of 2 equivalents of superoxide to peroxide and O2 with a second-order rate of 1.4 × 109 to 2.0 × 109 m−1s−1 under reaction conditions (pH 8.2) similar to our own (pH 8.0) (23), returning half of the O2 initially reduced to the level of superoxide back into solution. A 25% reduction of O2 consumption by superoxide dismutase would imply that 50% of the initially consumed O2 was reduced to the level of superoxide, a 50% reduction would imply that the entirety of catalytic throughput formed superoxide in the initial instance. Ferricytochrome c is reduced by superoxide with a second-order rate constant of 4.0 × 105 to 1.1 × 106 m−1s−1, depending on the ionic strength and pH of the solution (24), substantially faster than the uncatalyzed dismutation reaction (second-order rate constant of 105–107 m−1s−1 depending on the pH) (25, 26) Reduction of cytochrome c returns all of the O2 initially consumed as superoxide back to solution. A 50% reduction in O2 consumption would imply that half of the initially consumed O2 was reduced to the level of O2, complete abolishment of O2 consumption would imply that all O2 consumption resulted initially in the formation of superoxide.

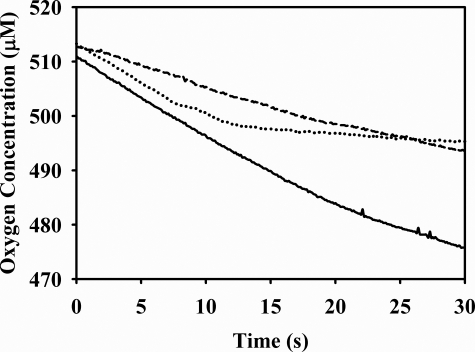

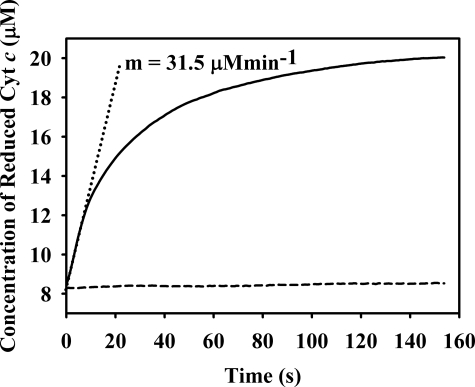

Under our standard conditions, with 60 nm enzyme and 1.0 mm sodium sulfite in 20 mm Tris-OAc, pH 8.0, at 4 °C at an O2 concentration of ∼500 μm, O2 consumption was 88.9 ± 0.2 μm/min (Fig. 4, solid line). In the presence of 200 units/ml superoxide dismutase, this rate of consumption was reduced by ∼45%, to 49.1 ± 0.4 μm/min (Fig. 4, dashed line), implying that ∼90% of O2 utilized in the reoxidation of plant sulfite oxidase is converted to superoxide. Addition of cytochrome c resulted in a reduction of oxygen consumption to 2.0 ± 0.1 μm/min, a decrease of 98% (Fig. 4, dotted line). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the vast majority of O2 consumption during turnover by plant sulfite oxidase, >90%, generates superoxide in the initial instance. Peroxide is formed only in the subsequent dismutation of superoxide.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of cytochrome c and superoxide dismutase on the steady-state rate of oxygen consumption by the plant sulfite oxidase reaction as monitored oximetrically. Representative transients for each reaction are shown. Solid line, reaction of sulfite oxidase (60 nm) with sulfite (1.0 mm) and ∼510 μm O2. Dashed line, same reaction in the presence of 200 units/ml superoxide dismutase. Dotted line, same reaction in the presence of 94.5 μm cytochrome c and no superoxide dismutase. Cytochrome c was added at ∼10 s after starting the reaction. The reaction was carried out in Tris acetate buffer, pH 8.0, at 4 °C.

We next examined the effect of pH and temperature on superoxide production, varying the pH (6.0–10.0) and the temperature (4–30 °C) (data not shown). Under all conditions examined, superoxide production was at least 95% and as high as 99% of the total O2 consumption.

Spectrophotometrically Monitored Cytochrome c Reduction in Steady-state Experiments

In addition to the above oxygraph experiments, spectrophotometric assays of superoxide generation were performed, following the superoxide dismutase-dependent reduction of cytochrome c directly by the spectral change at 550 nm. In these experiments, addition of superoxide dismutase will abolish any cytochrome c reduction that is due to the production of superoxide because the enzyme-catalyzed dismutation is much faster than cytochrome c reduction under our reaction conditions (and which is in turn considerably faster than the spontaneous dismutation reaction).

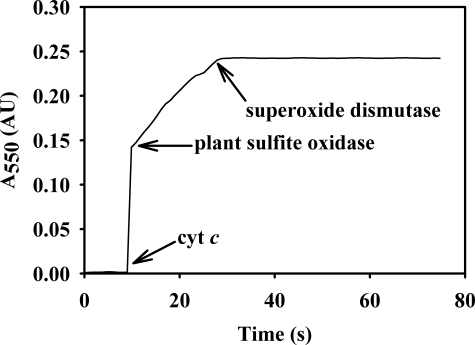

The rate of reduction of cytochrome c by 20 nm plant sulfite oxidase in the presence of 400 μm O2, was 31.5 ± 0.5 μm/min (Fig. 5, solid line). This rate agrees well with the rate seen in the oxygraph experiments above when the difference in enzyme concentrations in the two experiments is taken into account. Addition of superoxide dismutase to the reaction mix abolished reduction of cytochrome c essentially completely (Fig. 5, dashed line), indicating that cytochrome c reduction is in fact due to electron transfer from superoxide. The steady-state rate of cytochrome c reduction reflected a kobs for the reaction of 26.3 s−1. Because this experiment was performed at saturating sulfite concentrations, this value can be compared with the published values for kcat. Our value of 26.3 s−1 at 4 °C compares very favorably with the published value of 100 s−1 at 25 °C when the difference in temperature is taken into account (13).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of superoxide dismutase on cytochrome c reduction by plant sulfite oxidase reaction as monitored spectrophotometrically. Representative transients for each reaction are shown. Solid line, reaction of 20 nm plant sulfite oxidase with 1 mm sulfite and 532 μm O2 in the presence of 20 μm cytochrome c. Dashed line, same reaction in the presence of 200 units/ml superoxide dismutase. Dotted line, initial slope of the first reaction, yielding a value of 31.5 μm/min. The experiment was performed in Tris acetate buffer, pH 8.0, at 4 °C.

An experiment was also performed in which the entire process was monitored in a single transient, with cytochrome c, plant sulfite oxidase, and superoxide dismutase added sequentially as the spectral change associated with cytochrome c reduction was monitored. These results clearly showed that addition of superoxide dismutase, abolished cytochrome c reduction (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of superoxide dismutase on cytochrome c reduction by plant sulfite oxidase as monitored spectrophotometrically. The reaction was started by sequentially adding cytochrome c (∼20 μm final concentration) and 200 nm plant sulfite oxidase to a sulfite solution (1.0 mm) in a cuvette. Superoxide dismutase (200 units/ml) was added after a short time. Arrows on the spectrum indicate the points of cytochrome c, plant sulfite oxidase, and superoxide dismutase additions to the reaction mix. The experiment was performed in Tris acetate buffer, pH 8.0, at 4 °C.

Because of the ability of hydrogen peroxide to reoxidize cytochrome c, it was necessary to do a control in the presence 100 units/ml of catalase, which rapidly converts 2 equivalents of H2O2 to H2O and O2. The results showed that the initial rate of cytochrome c reduction was not affected and that only on longer time scales could this reoxidation become a factor (data not shown). These results suggest that the two-electron reduction of molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide is not the dominant path for reoxidation and that nearly all of the O2 consumed in the reoxidation of plant sulfite oxidase is converted to superoxide and is only subsequently converted to hydrogen peroxide nonenzymatically via spontaneous dismutation.

DISCUSSION

The molybdenum center of sulfite oxidase is very unusual in exhibiting significant reactivity toward O2; the molybdenum centers of other well characterized enzymes such as xanthine oxidase and vertebrate sulfite oxidases (with their heme prosthetic groups) react only very sluggishly with O2 and their reduced forms are essentially air-stable. We have demonstrated here that plant sulfite oxidase does not simply react rapidly with O2, but it does so in a way that produces superoxide essentially quantitatively. Hydrogen peroxide is only subsequently generated, as reported previously (5), in what is presumably the spontaneous dismutation of superoxide initially generated.

The reaction of plant sulfite oxidase with oxygen is strictly second-order, with a rate constant of 5.3 ± 0.3 × 104 m−1s−1 in 20 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.0, 4 °C. Time courses following the generation of superoxide in the course of enzyme reoxidation by its reduction of cytochrome c are biphasic, indicating that enzyme reoxidation occurs in two one-electron transfer steps. An initial fast transfer is followed by a slow second transfer with rates of 47.7 ± 0.4 s−1 and 7.5 ± 0.1 s−1, respectively. Given the very rapid rate of plant sulfite oxidase by sulfite (>1000 s−1) (8), it is evident that that the limiting step occurs during the oxidative half. We can, therefore, make a comparison between the reported kcat and the electron transfer rates that we have determined. Our data indicate an overall kox of 28 s−1 at 4 °C and an oxygen concentration of 532 μm. At 25 °C, kox is 116 s−1, which agrees with our value for kcat at 25 °C of 122 ± 1.1 s−1 and the published value of ∼100 s−1 (13). From the temperature dependence of kox over the range of 4–30 °C, an activation energy of Ea = 46.9 ± 1.2 kJ mol−1 can be estimated (data not shown). Our experimentally determined electron transfer rates for the oxidative half-reaction are in good agreement with previously published kinetic data. These data fully support the conclusion that plant sulfite oxidase generates superoxide.

Plant sulfite oxidase becomes one of only five peroxisomal proteins known to generate superoxide, the others being NADPH-dependent cytochrome b5 reductase (27) monodehydroascorbate reductase (27) and a protein of unidentified function that utilizes NADH as reductant (27–29). These are each believed to be the components of a peroxisomal membrane electron transport chain, with all three proteins found in the membrane. Although their superoxide generation may simply be adventitious and not represent a significant proportion of catalytic throughput, this is not the case with the plant sulfite oxidase. It is possible that the significant levels of superoxide (and peroxide) generated by these enzymes plays a physiological, possibly antipathogenic, role in plants.

Interestingly, neither vertebrate nor bacterial forms of sulfite oxidase seem to be able to react with oxygen at an appreciable rate. It is not known what determinants of the active site of plant sulfite oxidase render it so reactive toward O2. Indeed, the molybdenum center itself is virtually indistinguishable structurally from that of the vertebrate form of the enzyme, and most nearby amino acid residues, and in particular those responsible for binding substrate, are strictly conserved. Of known molybdenum centers in biology, only that of arsenite-complexed xanthine oxidase has been shown capable of direct reduction of oxygen, resulting in the production of superoxide (30).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant ES R01 012658 (to R. H.) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant Ha 3107/4-1 (to R. H. and R. R. M.).

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feng C., Tollin G., Enemark J. H. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 527–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen H. J., Fridovich I. J. (1971) J. Biol. Chem. 246, 359–366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niknahad H., O'Brien P. J. (2008) Chem. Biol. Interact. 174, 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schindelin H., Kisker C., Rajagopalan K. V. (2001) Adv. Protein Chem. 58, 47–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hänsch R., Lang C., Rennenberg H., Mendel R. R. (2007) Plant Biol. 9, 589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguey-Zinsou K. F., Bernhardt P. V., Kappler U., McEwan A. G. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 530–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hille R. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2757–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eilers T., Schwarz G., Brinkmann H., Witt C., Richter T., Nieder J., Koch B., Hille R., Hänsch R., Mendel R. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46989–46994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler D. L., Rajagopalan K. V. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247, 6566–6573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappler U., Bailey S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24999–25007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen H. J., Betcher-Lange S., Kessler D. L., Rajagopalan K. V. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247, 7759–7766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrader N., Fisher K., Theis K., Mendel R. R., Schwarz G., Kisker C. (2003) Structure 11, 1251–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemann C., Hood B. L., Fulton M., Hänsch R., Schwarz G., Mendel R. R., Kirk M. L., Hille R. (2005) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16567–16577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hänsch R., Lang C., Riebeseel E., Lindigkeit R., Gessler A., Rennenberg H., Mendel R. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6884–6888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowak K., Luniak N., Witt C., Wüstefeld Y., Wachter A., Mendel R. R., Hänsch R. (2004) Plant Cell Physiol. 45, 1889–1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temple C. A., Graf T. N., Rajagopalan K. V. (2000) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383, 281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massey V. (1959) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 34, 255–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oxygraph plus V1.01, (1996) Hansatech Instruments Ltd., King's Lynn, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCord J. M., Fridovich I. (1969) J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCord J. M., Fridovich I. (1968) J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5753–5760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fridovich I. (1970) J. Biol. Chem. 245, 4053–4057 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garton S. D., Garrett R. M., Rajagopalan K. V., Johnson M. K. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 2590–2591 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klug D., Rabani J., Fridovich I. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247, 4839–4842 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCord J. M., Crapo J. D., Fridovich I. (1977) in Superoxide and Superoxide Dismutates (Michelson A. M., McCord J. M., Fridovich I. eds) pp. 11–17, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCord J. M., Fridovich I. (1969) J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6056–6063 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolann B. J., Henriksen H., Ulvik R. J. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1156, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Huertas E., Corpus F. J., Sandalio L. M., del Rio L. A. (1999) Biochem. J. 337, 531–536 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Huertas E., Sandalio L. M., Gomez M., del Rio L. A. (1997) Free Rad. Res. 26, 497–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Rio L. A., Sandalio L. M., Corpas F. J., López-Huertas E., Palma J. M., Pastori G. M. (1998) Physiol. Plant. 104, 673–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart R. C., Hille R., Massey V. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 8892–8904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]