Abstract

Periostin (gene Postn) is a secreted extracellular matrix protein involved in cell recruitment and adhesion and plays an important role in odontogenesis. In bone, periostin is preferentially expressed in the periosteum, but its functional significance remains unclear. We investigated Postn−/− mice and their wild type littermates to elucidate the role of periostin in the skeletal response to moderate physical activity and direct axial compression of the tibia. Furthermore, we administered a sclerostin-blocking antibody to these mice in order to demonstrate the influence of sustained Sost expression in their altered bone phenotypes. Cancellous and cortical bone microarchitecture as well as bending strength were altered in Postn−/− compared with Postn+/+ mice. Exercise and axial compression both significantly increased bone mineral density and trabecular and cortical microarchitecture as well as biomechanical properties of the long bones in Postn+/+ mice by increasing the bone formation activity, particularly at the periosteum. These changes correlated with an increase of periostin expression and a consecutive decrease of Sost in the stimulated bones. In contrast, mechanical stimuli had no effect on the skeletal properties of Postn−/− mice, where base-line expression of Sost levels were higher than Postn+/+ and remained unchanged following axial compression. In turn, the concomitant injection of sclerostin-blocking antibody rescued the bone biomechanical response in Postn−/− mice. Taken together, these results indicate that the matricellular periostin protein is required for Sost inhibition and thereby plays an important role in the determination of bone mass and microstructural in response to loading.

Introduction

Periostin gene (Postn) expression was first identified using subtractive hybridization techniques on MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells and initially named osteoblast-specific factor 2 (OSF-2) (1). Subsequently, several developmentally regulated and differentially spliced isoforms of Postn have been identified in both mice and humans and are expressed in many non-skeletal tissues, including stromal cells from ovary, breast, colon, and brain tumors. Periostin is a 90-kDa secreted extracellular matrix protein that binds integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5, thereby regulating cell adhesion and mobility (2, 3). Periostin potently promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer cells by augmenting their survival via the Akt/protein kinase B pathway (4). Besides, periostin is predominantly expressed in tissues subject to mechanical stress, suggesting a potential function of periostin in maintaining the structure and integrity of connective tissues. For example, periostin is expressed by cardiac fibroblasts (5–7), where protein expression increases after heart failure and in a model of overload hypertrophy of the heart (8). Periostin is also linked to type I collagen in the periodontal ligament, where it regulates fibrillogenesis and consequently the biomechanical properties of fibrous connective tissues around the tooth (9). Its expression is increased in the periodontal ligament upon mechanical loading and is essential for the integrity and function of this ligament during occlusal loading (10, 11). Moreover, in vitro application of tensional forces to periodontal cells increases Postn expression. In contrast, following in vivo masticatory unloading, Postn mRNA levels decrease (11, 12). Postn-deficient mice (Postn−/−) show severe alterations in tooth (incisor) eruption, resulting from a failure to digest collagen fibers in the shear zone of the periodontal ligament (13, 14). As a consequence, the enamel and dentin of the incisors is compressed and disorganized.

In MC3T3-E1 osteoblast cells, periostin is secreted into the collagen matrix and regulates cell adhesion and differentiation (15, 16). Inactivation of Postn using specific periostin-blocking antibodies leads to a severe reduction of osteoblast-specific differentiation markers, such as type I collagen, osteocalcin, osteopontin, and alkaline phosphatase (16). In the rodent adult skeleton, Postn expression appears to be restricted to the periosteum, without any reported expression within the endosteum (15). For this reason, Postn has recently been used to identify periosteal osteoblasts ex vivo (17). During fracture repair, Postn mRNA is up-regulated 2-fold and localizes to preosteoblastic cells within the periosteum as well as in undifferentiated mesenchymal cells close to the fracture site (18). Furthermore, Postn−/− mice have shorter long bones, suggesting a disruption of the cartilaginous growth plate (13). Whether periostin influences bone turnover, however, remains to be elucidated.

In young and adult rats, treadmill exercise, typically 1 h/day, is known to increase cortical and cancellous bone mass of the tibia due to enhanced bone formation and reduced bone resorption (19–21). Cyclic axial compression of the ulna or tibia can also increase bone mass and size in rodents (22). In these models, stimulation of bone formation occurs mainly at the periosteal rather than endocortical surfaces (23–25). This bone (re)modeling effect largely depends on the suppression of sclerostin gene (Sost) expression by osteocytes (26), which then allows for the stimulation of Wnt/LRP5/β-catenin signaling within lining osteoblasts (27). Interestingly, preliminary studies suggest that sclerostin antagonistic activity on Wnt signaling can be inhibited by periostin (28). These observations led us to hypothesize that periostin modulates bone turnover, specifically in response to mechanical stimulation. In order to test this hypothesis, we characterized bone mass, microarchitecture, and strength in Postn−/− mice. We show that Postn mRNA and protein expression in bone is stimulated by mechanical loading, which precedes inhibition of Sost gene expression. Furthermore, we report that periostin is required for the complete biomechanical responses of the skeleton to both axial compression and physical activity and that sclerostin-blocking antibodies restore the bone biomechanical response in Postn−/− mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Postn−LacZ knock-in mice (Postn−/−) were generated as reported previously (13). Postn−/− mice were subsequently bred with C57BL/6J mice, and tail DNA analyzed by PCR was used to identify Postn heterozygous mice. We interbred mice that were heterozygous carriers of this mutation and obtained wild-type (Postn+/+), heterozygous (Postn+/−), and homozygous mutant (Postn−/−) offspring in the expected Mendelian genetic frequencies. These mice were subsequently back-crossed for 6 generations, resulting in a genome of 98% C57BL/6J. Mice were housed five per cage, maintained under standard non-barrier conditions, and had access to water and soft diet ad libitum (2019 Teklad, Harlan Laboratories, Shardlow, UK). A soft diet was chosen to reduce malnutrition in the Postn−/− mice, which was previously observed under a standard diet due to the enamel and dentin defects of the incisors and molars (13). All of the mice received the same diet throughout the experiment. 12- and 14 week-old male mice were used for the treadmill exercise and the loading studies, respectively. An additional group of mice were sacrificed at 12 weeks old to describe the bone phenotype of the Postn-deficient mice at base line (n = 10 mice/group). Animal procedures were approved by the University of Geneva School of Medicine Ethical Committee and the State of Geneva Veterinarian Office.

In Vivo Axial Compression

The loading apparatus was specifically adapted for mouse tibiae as previously described (29). Custom molded pads were placed on the axes to apply compression on the bone extremities. The tibiae were then placed on the stimulation machine between the moving pad on the proximal side (the knee) and the fixed pad on the distal side (the foot). Strain magnitudes were calibrated ex vivo using miniature strain gauges bound to the midshaft tibia surface, as previously reported (24, 29). The left tibia of each mouse was subjected to dynamic axial stimulation, using the following parameters: peak load = 12 newtons; peak strain (midshaft cortex) = 1500 micro strain; pulse period (trapeze-shaped pulse) = 0.1 s; rest time between pulses = 10 s; full cycle frequency (pulse + rest) = 0.1 Hz. A total of 40 cycles (∼7 min) were applied per day. The non-stimulated right tibia served as an internal control. The mice used to study the bone response to direct axial compression were stimulated on 3 alternate days/week for 2 weeks and sacrificed 3 days later. To measure dynamic indices of bone formation, mice received subcutaneous injections of calcein (25 mg/kg; Sigma) 9 and 2 days before euthanasia. The mice used for immunohistochemical staining of periostin were stimulated for 2 consecutive days and then sacrificed on day 3. The mice used for real-time analyses were stimulated for a single session (1 day) and sacrificed 6 or 24 h later. For the axial compression procedure, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamin xylasine. The total duration of anesthesia lasted just a bit longer than the loading period, up to a maximum of 20 min. None of the mice showed signs of lameness or decreased activity levels after recovery from anesthesia (n = 10 mice/group).

This loading experiment was repeated in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice with concomitant intravenous injection of a sclerostin-blocking antibody (Sost-Ab2; 12 mg/kg/week) or a control antibody (anti-cyclosporin A, Ig-G2A) for 2 weeks (n = 6 mice/group/genotype). The anti-sclerostin antibody was isolated from a combinatorial antibody library using phage display technology (MorphoSys AG, Martinsried, Germany) and administered 1 h prior to axial compression at a concentration previously found to have mild anabolic effects on bone (30).

Measurements of the Strain Distribution

Nine mice were sacrificed at the age of 14 weeks, and the tibiae were immediately excised. Soft tissues were removed, and the tibia were cleaned with acetone. The tibiae were separated randomly into three groups of six corresponding to three zones of tests on the tibia: zone 1, anteroproximal; zone 2, anterotibial crest; zone 3, posterodistal. Each tibia received a single element foil strain gauge (EA-06-015LA-120, Vishay Micro-measurements, Raleigh, NC) aligned with the long axis bound to bone surface with cyanoacrylate. The gauge was connected to a tension amplifier and digital recorder (DAQ NI9215, National Instruments, Switzerland). Gauge location allowed for the analysis of the whole strain submitted to the bone during an axial compression of the tibia without any space left between the gauges.

Exercise Training

Male mice (12 weeks old) were randomly divided into exercise-trained and rested groups for each genotype, Postn−/−, Postn+/−, and Postn+/+ mice. The mice were trained 5 days/week for 6 weeks. During the first week, the treadmill speed and the duration of each running session were gradually increased from 8 m/min for 10 min to 16 m/min for 40 min. For the last 5 weeks, the running sessions consisted of 16 m/min for 40 min with a treadmill inclination of 8°, corresponding to moderate exercise for these mice at this specific age (31). Rested mice serving as control were handled twice daily at 1-h intervals to mimic the stress induced by handling before and after running. It should be noted that the above interventions do not affect food intake in mice (data not shown). At the end of the study (i.e. at 18 weeks of age), all mice were sacrificed with an overdose of ketamin xylasine (n = 8 mice/group). To measure dynamic indices of bone formation, mice received subcutaneous injections of calcein 9 and 2 days before euthanasia.

In Vivo Measurement of Bone Mineral Density (Exercise Training)

Total body, femoral, and spinal bone mineral density (BMD; g/cm2) were measured in vivo, at 12 and 18 weeks of age in the exercise experiment and at 13 and 16 weeks of age in the axial compression experiment, by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (PIXImus2, GE lunar, Madison, WI) (32).

In Vivo Measurement of Skeletal Morphology and Microarchitecture (Axial Compression)

A high resolution in vivo microcomputed tomography system (microCT Skyscan 1076, Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium) was used to scan the left and right tibiae. The in vivo microCT system consists of an x-ray source and detector that rotates around the animal bed. The machine is equipped with a 100-kV x-ray source with a spot size of 5 μm. Each scan lasted ∼20 min, resulting in shadow projections with a pixel size of 10 μm. A modified Feldkamp algorithm, using undersampling to reduce noise, was applied to the scan data, resulting in reconstructed three-dimensional data sets with a voxel size of 20 μm. (33). The mice were scanned at 14 weeks of age before loading and at 16 weeks of age, 3 days after the last loading. A detailed description and validation of the algorithm is published elsewhere (34). Cortical and trabecular bones were separated manually with “CT Analyzer” software (Skyscan, Aartselaar, Belgium). For a description of the bone microarchitecture parameters analyzed, see below.

Ex Vivo Measurement of Morphology and Microarchitecture (Exercise Training)

Microcomputed tomography (microCT UCT40, Scanco Medical AG, Basserdorf, Switzerland) was used to assess trabecular bone volume fraction and microarchitecture in the excised 5th lumber spine body and distal femur and cortical bone geometry at the midshaft femoral diaphysis as described previously (35). Briefly, trabecular and cortical bone regions were evaluated using isotropic 12-μm voxels. For the vertebral trabecular region, we evaluated 250 transverse CT slices between the cranial and caudal end plates, excluding 100 μm near each end plate. For the femoral and tibial trabecular region, to eliminate the primary spongious, we analyzed 100 slices from the 50 slices under the distal growth plate. Femoral cortical geometry was assessed using 50 continuous CT slides (600 μm) located at the femoral midshaft. Images were segmented using an adaptative-iterative thresholding approach rather than a fixed threshold. Morphometric variables were computed from binarized images using direct, three-dimensional techniques that do not rely on prior assumptions about the underlying structure (36). For the trabecular bone regions, we assessed the bone volume fraction (BV/TV, percentage), trabecular thickness (TbTh, μm), trabecular number (TbN, mm−1), trabecular connectivity density (Tb Conn density, mm−3), and structural model index (SMI). The structure model index was measured to determine the prevalence of platelike or rodlike trabecular structures, where 0 represents “plates” and 3 represents “rods” (36). For cortical bone at the femoral and tibial midshaft, we measured the cortical tissue volume (CtTV, mm3), bone volume (CtBV, mm3), marrow volume (BMaV, mm3), and average cortical width (CtTh, μm).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR

The whole tibia was excised, and both tibial extremities were cut to remove the bone marrow from the diaphysis, by flushing with cold phosphate-buffered saline. Tibial diaphysis and extremities were immediately pulverized to a fine powder and homogenized in peqGold Trifast (peQLab Biotechnologie GmbH) using a FastPrep system apparatus (QBiogene) in order to achieve quantitative RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted and then purified on minicolumns (RNeasy minikit, Qiagen) in combination with a deoxyribonuclease treatment (RNase-free DNase set, Qiagen) to avoid DNA contamination.

Single-stranded cDNA templates for quantitative real-time PCR analyses were carried out using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using predesigned TaqMan® gene expression assays (references as follows: B2m, Mm00437762_m1; Sost, Mm00470479_m1; Postn, Mm00450111_m1) (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) consisting of two unlabeled primers and a FAMTM dye-labeled TaqMan® MGB probe and the correspondent buffer TaqMan® universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). A Biomek 2000 robot (Beckman Coulter, Nyon, Switzerland) was used for liquid handling (10 μl) in 384-well plates with 3 replicates/sample. The cDNA was PCR-amplified in a 7900HT SDS System, and raw threshold cycle (Ct) values were obtained from SDS version 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantities (RQ) were calculated with the formula RQ = E − Ct using an efficiency (E) of 2 by default. For each gene, the highest quantity was arbitrarily designated a value of 1.0. The mean quantity was calculated from triplicates for each sample, and this quantity was normalized to the similarly measured mean quantity of the β2-microglobulin normalization gene. Finally, normalized quantities were averaged for 3–4 animals and represented as mean ± S.E.

Immunohistochemistry

The right and left tibiae were excised and subsequently fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. They were then decalcified in 19% EDTA and 4% phosphate-buffered formalin for 3 weeks. The tibiae were then dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol, cleared in Propar (Anatech LTD, Battle Creek, MI), and embedded in paraffin blocks. 10-μm-thick sections were cut from the blocks at the tibia midshaft level using a RM2155 microtome (Leica, Germany) and mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher). Sections were air-dried overnight at room temperature. Prior to staining, they were incubated at 60 °C for 1 h, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in a descending series of ethanol. Deparaffinized slides were pretreated in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase and rinsed in tap water followed by nonspecific avidin/biotin blocking (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer's directions. All incubations took place in a humidified chamber. Additional protein blocking was accomplished with Protein Block-Serum Free (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Using the Vectastain Elite ABC (rabbit IgG) kit (Vector Laboratories), the slides were incubated in 1.5% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature. The primary antibody (rabbit anti-periostin) (Ed Krug, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) was diluted in antibody diluent (DAKO) to a final concentration of 1:6000 and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The following day, slides were rinsed in Wash Buffer (DAKO) for 15 min on a rocker at room temperature and incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit (Vectastain kit) secondary antibody diluted 1:1000 for 30 min at room temperature, followed by another rinse in Wash Buffer for 15 min on a rocker at room temperature. The ABC reagent from the Vector kit was prepared according to the manufacturer's directions at a dilution of 1:250, and the slides were incubated in it for 30 min at room temperature and rinsed, as above, in Wash Buffer. All incubation steps were performed at room temperature, and all rinse steps employed the DAKO Wash Buffer at room temperature on a rocker. The following protocol was used: incubation in streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase diluted at 1:100 for 30 min and washed for 15 min. Slides were developed in a working solution of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB Substrate Kit for Peroxidase Kit, Vector Laboratories) prepared according to the manufacturer's directions for 10 min at room temperature. Following a final rinse in deionized water, the slides were counterstained in Weak Methyl Green and mounted in Cytoseal 60 (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Positive periostin staining was quantified using a microscope interfaced with an image analysis system (Leica Corp.).

Histomorphometry

To measure dynamic indices of bone formation, mice received subcutaneous injections of calcein (10 mg/kg; Sigma) 9 and 2 days before euthanasia. Tibiae were embedded in methyl-methacrylate (Merck), and 8-μm-thick transversal sections of the midshaft were cut with a Leica Corp. Polycut E microtome (Leica Corp. Microsystems AG, Glattburg, Switzerland) and mounted unstained for evaluation of fluorescence. 5-μm-thick sagittal sections were stained with modified Goldner's trichrome, and histomorphometric measurements were performed on the secondary spongiosa of the proximal tibia metaphysis and on the endocortical and periosteal bone surfaces in the middle of the tibia, using a Leica Corp. Q image analyzer at ×40 magnification. All parameters were calculated and expressed according to standard formulas and nomenclatures (37): mineral apposition rate (MAR, μm/day), single-labeled surface (sLS/BS, percentage), and double-labeled surface (dLS/BS, percentage). Mineralizing surface per bone surface (MS/BS, percentage) was calculated by adding dLS/BS and one-half sLS/BS. Bone formation rate (BFR/BS, μm3/μm2/day) was calculated as the product of MS/BS and MAR.

Preparation of Specimens for Transmission Electron Microscopy

The left femur of three Postn−/− and Postn+/+ mice (12 weeks old) was excised, soft tissue was removed, and the bones were prepared for electron microscopy. The tissue was fixed in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 24 h. Samples were then washed three times with Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and decalcified 4 days at 4 °C by incubation in a 10% EDTA/Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, solution replaced every 24 h. The mid-diaphysis was isolated and postfixed with 1% osmium tetraoxide and 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then dehydrated, embedded in Epon resin, and processed for electron microscopy as described previously (38). Ultrathin sections were finally contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Technai 20 electron microscope (FEI Co., Eindhoven, Netherlands). Morphometric measurements of the number and size of collagen fibrils were performed with Metamorph software on 20 pictures/sample.

Testing of Mechanical Resistance

The night before mechanical testing, bones were thawed slowly at 7 °C and then maintained at room temperature. The fibula was removed, the length of the tibia (distance from intermalleolar to intercondylar region) was measured using calipers with an integrated electronic digital display, and the midpoint of the shaft was determined. The tibia then was placed on the material testing machine on two supports separated by a distance of 9.9 mm, and load was applied to the midpoint of the shaft, thus creating a three-point bending test. Between each preparation step, the specimens were kept immersed in physiological solution. The mechanical resistance to failure was tested using a servo-controlled electromechanical system (Instron 1114, Instron Corp., High Wycombe, UK) with actuator displaced at 2 mm/min. Both displacement and load were recorded. Ultimate force (maximal load, measured in newtons), stiffness (slope of the linear part of the curve, representing the elastic deformation, N/mm), and energy (surface under the curve, N·mm) were calculated. Ultimate stress (N/mm2) and Young's modulus (megapascals) were determined by the equations previously described by Turner and Burr (39). Reproducibility was 5.8% for proximal tibia and 3.3% for midshaft tibia, and the coefficient of variation of paired sample measurements (left/right) was evaluated.

Data Analysis

We first tested the effects of loading or exercise within groups (Postn−/−, Postn+/−, and Postn+/+) by paired or unpaired t tests. In the mechanical loading experiments, we compared stimulated and non-stimulated tibia in the same animal using a paired t test. For the exercise investigation, we compared rested versus trained animals using unpaired t tests. We then tested the effects of repeated measures within groups (stimulated/non-stimulated and exercise/sedentary) by one-way ANOVA repeat measurements with the genotype employed as a factor. To compare the effect of genotype and the response to loading (mechanical loading and exercise), we used a two-way ANOVA. As appropriate, post hoc testing was performed using Fisher's protected least squares difference (PLSD). The p of interaction between the genotype and loading (mechanical stimulation or exercise) is only indicated when it was found to be significant. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Exercise Versus Rested Conditions in Postn−/− Mice

We first evaluated the role of periostin during the skeletal response to physiological mechanical stimuli induced by moderate physical activity. For this purpose, 12-week-old mice were trained 5 days/week for 6 weeks on a treadmill, at 16 m/min for 40 min/day with a treadmill inclination of 8° (31).

Body Weight, Body Composition, and Bone Mineral Density

Overall, body weight tended to be lower in Postn−/− mice compared with Postn+/− and Postn+/+ mice but increased significantly over 5 weeks in both resting and exercise conditions in Postn+/− and Postn−/− mice (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S1). The percentages of lean and fat mass were similar in all groups and not significantly changed by moderate exercise.

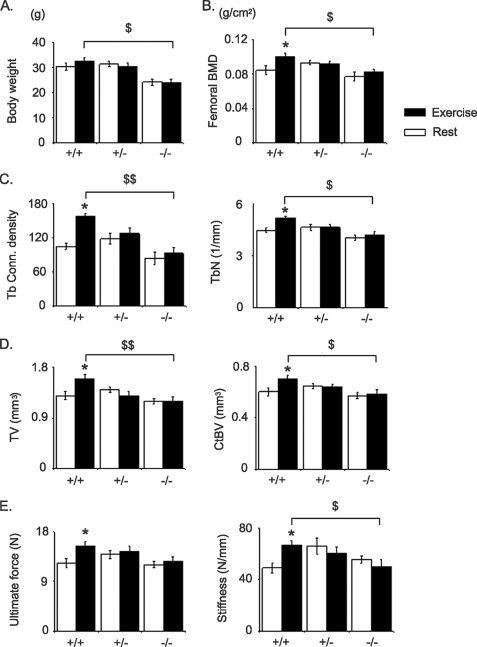

FIGURE 1.

Effects of treadmill exercise on the femur. Bars, mean ± S.E. measured after 5 weeks of exercise (closed bars) or rested (open bars) in Postn+/+, Postn+/−, and Postn−/− mice. A, body weight. B, BMD at total femur. C, Tb bone microarchitecture at distal femur. D, cortical bone microarchitecture at femur midshaft. E, biomechanical properties of the cortical femur measured by three-point bending. *, p < 0.05, unpaired t test compared with rested group within periostin group; $, p < 0.05; $$, p < 0.01 unpaired Postn+/+ versus Postn−/− mice by post hoc Fisher's PLSD following 2F-ANOVA. Shown are means ± S.E.

BMD was similar in all groups under resting conditions; however, in the exercise groups, BMD at the femur and tibia were significantly lower in Postn−/− mice compared with Postn+/− and Postn+/+ (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S1). Indeed, in Postn+/+ mice, exercise increased BMD +20.2% in femur and +10.5% in tibia above base line (versus +2.2% and +1.8% in the rested group, respectively; p < 0.05), whereas in Postn+/− and Postn−/− mice, BMD gain did not differ between exercise and resting groups (interaction between Postn and exercise, p < 0.05, by 2F-ANOVA) (supplemental Table S1).

Bone Microarchitecture

At 12 weeks of age (base line), bone microarchitecture evaluated at distal femur by ex vivo microCT showed a lower TbN and a lower BV/TV, more separation between trabeculae (TbSp), and a more rodlike trabecular shape (higher SMI) in Postn−/− compared with Postn+/+ mice. Moreover, femur midshaft size was smaller in Postn−/− mice (i.e. a lower TV) and contained lower CtBV (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of femoral bone microarchitecture and biomechanical properties in periostin-deficient mice

Cancellous bone microarchitecture was evaluated at distal femur and cortical microarchitecture at midshaft femur by ex vivo microCT at 12 weeks of age (base line, n = 10 mice/group). Bending strength of femur midshaft was evaluated by a three-point bending test on excised femur.

| Parameters | Postn+/+ | Postn+/− | Postn−/− | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trabecular | BV/TV (%) | 21.6 ± 1.2 | 15.2 ± 1.1a | 11.1 ± 1.5a | 0.02 |

| Conn density (1/mm3) | 180.1 ± 15.4 | 129.5 ± 10.7a | 101.4 ± 7.1a | 0.02 | |

| Tb.Th (μm) | 56 ± 4 | 52 ± 3 | 47 ± 4 | 0.39 | |

| Tb.N | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1a | 4.4 ± 0.04a | 0.02 | |

| Tb.Sp (μm) | 177 ± 5 | 210 ± 6a | 225 ± 2a | 0.02 | |

| SMI | 1.5 ± 0.09 | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 2.5 ± 0.1a | 0.02 | |

| Cortical | CtTV (mm3) | 1.31 ± 0.08 | 1.30 ± 0.03 | 1.12 ± 0.04a,b | 0.04 |

| CtBV (mm3) | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 0.46 ± 0.02a | 0.04 | |

| CtTh (μm) | 280 ± 15 | 271 ± 8 | 261 ± 11 | 0.43 | |

| BMaV (μm3) | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.03a,b | 0.04 | |

| Bending strength | Ultimate force (N) | 15.7 ± 0.8 | 13.9 ± 0.8 | 11.4 ± 1.0a | 0.04 |

| Ultimate Stress (N/mm2) | 546 ± 65 | 537 ± 89 | 392 ± 63a | 0.05 | |

| Elastic Energy (N·mm) | 1.67 ± 0.2 | 1.30 ± 0.2 | 1.33 ± 0.2 | 0.22 | |

| Plastic Energy (N·mm) | 2.95 ± 0.5 | 2.80 ± 0.2 | 2.60 ± 0.4 | 0.47 | |

| Stiffness (N/mm) | 64.8 ± 6.3 | 53.8 ± 5.4 | 47.2 ± 6.8a | 0.04 | |

| Young's modulus (megapascals) | 37888 ± 3284 | 31457 ± 4050 | 27427 ± 3864a | 0.04 |

a p < 0.05 versus Postn+/+ mice, by post hoc Fisher's PLSD. Means ± S.E.; p value for differences between periostin groups (1F-ANOVA).

b p < 0.05 versus Postn+/− mice, by post hoc Fisher's PLSD. Means ± S.E.; p value for differences between periostin groups (1F-ANOVA).

Compared with resting conditions, exercise significantly increased TbN (+18.2%, p < 0.05) and connectivity-density (+52.1%, p < 0.05), decreased TbSp (−14.0%, p < 0.05), and had borderline effects on BV/TV (+14.90, p = 0.09) in Postn+/+ mice (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S2). In contrast, exercise had no effect on trabecular bone parameters in either Postn+/− or Postn−/− mice (interaction between periostin presence and exercise, p < 0.05 for TbN and connectivity density, by 2F-ANOVA). At the midshaft femur, exercise significantly increased TV, CtBV, and BMaV in the Postn+/+ mice (+23.1, +11.2, and +12.4% versus rest, respectively, all p < 0.05) but not in Postn−/− or Postn+/− mice (Fig. 1 and supplemental Table S2). As a result, the postexercise cortical and trabecular bone microarchitecture was significantly improved in Postn+/+ mice, whereas Postn−/− littermates showed minimal change.

Biomechanical Properties

To evaluate whether differences in cortical microarchitecture were translated into differences in bone strength, femurs were tested in bending assays. At base line, Postn−/− mice had lower ultimate force (−27.4%, p < 0.05), ultimate stress (−28.2%, p < 0.05), and Young's modulus (−27.6%, p < 0.05) compared with Postn+/+ mice, consistent with their smaller cortical bone volume and reduced material properties (Table 1), whereas Postn+/− mice exhibited the expected intermediate biomechanical properties between Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice (Table 1). Exercise significantly increased ultimate force and stiffness (+24.2 and +36.7%, respectively, versus rest, all p < 0.05) in Postn+/+ mice but not in Postn−/− or Postn+/− mice (Fig. 1). Young's modulus, or the modulus of elasticity, was also significantly higher after 5 weeks of exercise in Postn+/+ compared with Postn−/− mice (37,116 ± 3528 versus 22,239 ± 6363, p = 0.04), with intermediate values in Postn+/− mice (31,192 ± 4383).

Bone Turnover

We next evaluated the relative indices of bone turnover in tibia from Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice by histomorphometry. In resting conditions, few differences were observed in bone turnover between Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice besides a 33% lower MAR on trabecular bone surfaces in the latter; nor were there any significant differences in osteoblast and osteoclast number per bone surface (Table 2). Although we did not observe any significant effects of exercise on osteoblast number or surface, exercise did significantly stimulate bone formation indices (MAR, BFR, and MPm/BPm) on periosteal and, to a lesser extent, trabecular surfaces in Postn+/+ mice, with similar trends at the endocortical surface, whereas no significant effect on bone turnover was observed in Postn−/− mice (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Influence of periostin and exercise on bone turnover at cortical and trabecular bone surfaces

Bone histomorphometry performed at tibia metaphysis (trabecular) and diaphysis (periosteal and endocortical) after 5 weeks of exercise or resting conditions. Ps, periosteum; Ec, endocortical; Tb, trabecular.

| Parameters | Postn+/+ | Postn−/− | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | ||||

| Periosteal | Ps MAR (μm/day) | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.70 |

| Ps BFR/BPm (μm2/μm/day) | 0.004 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 0.31 | |

| Ps MPm/BPm (%) | 0.19 ± 0.1 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.59 | |

| Endocortical | Ec MAR (μm/day) | 0.15 ± 0.15 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.72 |

| Ec BFR/BPm (μm2/μm/day) | 0.003 ± 0.017 | 0.01 ± 0.006 | 0.52 | |

| Ec MPm/BPm (%) | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | 0.20 | |

| Trabecular | Tb MAR (μm/day) | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.11a | 0.02 |

| Tb BFR/BS (μm2/μm3/day) | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| Tb MS/BS (%) | 32.8 ± 5.3 | 20.9 ± 7.4 | 0.16 | |

| OcS/BS (%) | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 0.75 | |

| OcN/BPm (mm−1) | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 0.68 | |

| ObS/BS (%) | 10.6 ± 1.2 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 0.36 | |

| ObN/BPm (mm−1) | 10.0 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 0.10 | |

| Exercise | ||||

| Periosteal | Ps MAR (μm/day) | 0.44 ± 0.04b | 0.30 ± 0.16 | 0.13 |

| Ps BFR/BPm (μm2/μm/day) | 0.03 ± 0.008b | 0.018 ± 0.011 | 0.22 | |

| Ps MPm/BPm (%) | 0.59 ± 0.14b | 0.30 ± 0.11 | 0.09 | |

| Endocortical | Ec MAR (μm/day) | 0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.22 ± 0.10 | 0.73 |

| Ec BFR/BPm (μm2/μm/day) | 0.008 ± 0.12 | 0.006 ± 0.004 | 0.69 | |

| Ec MPm/BPm (%) | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.10 | 0.54 | |

| Trabecular | Tb MAR (μm/day) | 0.82 ± 0.15b | 0.44 ± 0.03a | 0.01 |

| Tb BFR/BS (μm2/μm3/day) | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.13 ± 0.10a | 0.02 | |

| Tb MS/BS (%) | 43.4 ± 8.2 | 29.8 ± 7.3 | 0.15 | |

| OcS/BS (%) | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 7.8 ± 2.3 | 0.22 | |

| OcN/BPm (mm−1) | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 0.17 | |

| ObS/BS (%) | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 0.53 | |

| ObN/BPm (mm−1) | 6.2 ± 1.2 | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 0.53 | |

a p < 0.05 versus Postn+/+ mice (Fisher's PLSD) (n = 8 mice/group) (means ± S.E.).

b p < 0.05 versus rested mice (unpaired t test) (n = 8 mice/group) (means ± S.E.).

Skeletal Response to Axial Compression

Having established that periostin modulates the skeletal response to moderate physical activity, we next investigated whether mechanotransduction of direct mechanical strains on bone also required the presence of periostin. More specifically, we wanted to evaluate whether an intense biomechanical stimulus could overcome the effects of deficient Postn expression in bone. For this purpose, mice were subjected to direct axial compression of the tibia in vivo for 2 weeks (see “Experimental Procedures” for details), and longitudinal changes in microarchitecture were assessed by in vivo microCT.

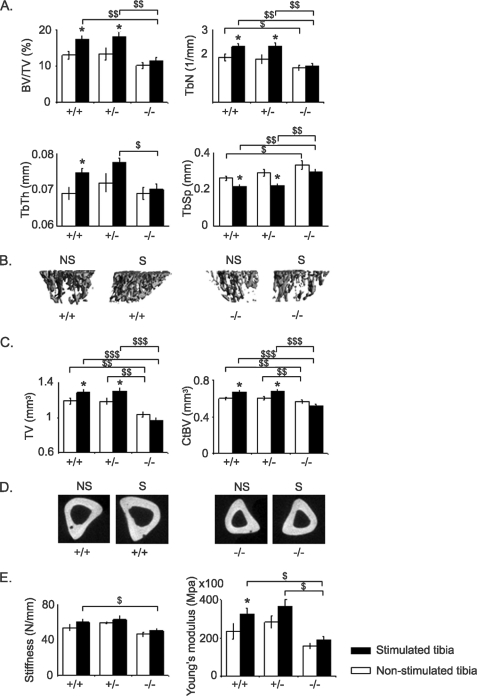

Bone Microarchitecture and Strength

Trabecular and cortical bone microarchitectural parameters of the non-stimulated and stimulated tibiae at base line were significantly lower in Postn−/− mice and intermediate in Postn+/− mice when compared with Postn+/+ littermates (Table 3). Axial compression significantly increased BV/TV (+58.2% versus +4.0% above base line in the stimulated and non-stimulated tibia, respectively, p < 0.05), TbN, TbTh, TV, CtBV, and CtTh in Postn+/+ mice (Table 3 and Fig. 2, A–D). Contrasting with their response to moderate physical activity (above), haploinsufficient Postn+/− mice had changes of bone microarchitecture following axial compression that were similar to those in Postn+/+ mice (Table 3 and Fig. 2). In contrast, in the Postn−/− mice, no significant differences were observed in either trabecular or cortical bone gain between stimulated and non-stimulated bones. These periostin-dependent changes in the cortical bone response to axial compression were translated into significant differences in bone biomechanical properties, such as stiffness and Young's modulus, that were significantly higher in Postn+/+ and Postn+/− mice compared with Postn−/− mice (Fig. 2E).

TABLE 3.

Influence of periostin on changes of tibial bone microarchitecture in response to axial compression

Cancellous bone microarchitecture was evaluated at proximal tibia and cortical microarchitecture at midshaft tibia in the axially compressed bone and its controlateral non-stimulated control bone by in-vivo microCT at base line (14 weeks old) and after 2 weeks (n = 10 mice/group).

| Parameters |

Postn+/+ |

Postn+/− |

Postn−/− |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2 weeks | Baseline | 2 weeks | Baseline | 2 weeks | |||

| Non-stimulated | ||||||||

| Trabecular | BV/TV (%) | 12.5 ± 1.4 | 13.0 ± 1.1 | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | 10.1 ± 0.9a | 0.01 |

| TbN (mm−1) | 1.95 ± 0.19 | 1.87 ± 0.13 | 1.71 ± 0.26 | 1.80 ± 0.18 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 1.45 ± 0.11a | 0.008 | |

| TbTh (μm) | 63.21 ± 1.4 | 69.10 ± 1.6 | 67.3 ± 1.6 | 71.9 ± 2.5 | 61.0 ± 1.7 | 69.0 ± 1.6a | 0.20 | |

| TbSp (mm) | 234 ± 12 | 262 ± 11 | 282 ± 28 | 291 ± 19 | 363 ± 16 | 335 ± 22 | 0.03 | |

| SMI | 2.39 ± 0.06 | 2.42 ± 0.04 | 2.43 ± 0.09 | 2.32 ± 0.07 | 2.60 ± 0.03 | 2.45 ± 0.04a | 0.16 | |

| Cortical | TV (mm3) | 0.89 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.04 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 1.04 ± 0.03a | 0.01 |

| BV (mm3) | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.02a | 0.04 | |

| CTh (μm) | 248 ± 5 | 237 ± 3 | 245 ± 9 | 236 ± 3 | 217 ± 3 | 241 ± 6a | 0.38 | |

| BMaV (μm3) | 352 ± 15 | 594 ± 24 | 318 ± 14 | 593 ± 24a | 235 ± 10 | 447 ± 16a | 0.01 | |

| Stimulated | ||||||||

| Trabecular | BV/TV (%) | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 17.4 ± 0.9a,b | 10.8 ± 1.3 | 18.2 ± 1.1a,b | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 11.4 ± 0.9a | 0.001 |

| TbN (1/mm) | 1.77 ± 0.17 | 2.32 ± 0.12a,b | 1.61 ± 0.17 | 2.33 ± 0.13a,b | 1.18 ± 0.12 | 1.51 ± 0.10a | 0.001 | |

| TbTh (μm) | 61.52 ± 1.0 | 74.69 ± 1.4a,b | 66.0 ± 1.7 | 77.7 ± 1.2a | 60.1 ± 1.5 | 70.1 ± 1.5a | 0.03 | |

| TbSp (mm) | 245 ± 14 | 218 ± 8a,b | 268 ± 18 | 223 ± 8a,b | 326 ± 21 | 299 ± 14 | 0.01 | |

| SMI | 2.50 ± 0.06 | 2.40 ± 0.06 | 2.56 ± 0.04 | 2.33 ± 0.05a | 2.65 ± 0.04 | 2.41 ± 0.03a | 0.4 | |

| Cortical | TV (mm3) | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 1.29 ± 0.04a,b | 0.85 ± 0.02 | 1.31 ± 0.04a,b | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.03a | 0.001 |

| BV (mm3) | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.67 ± 0.01a,b | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.02a,b | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.02a | 0.001 | |

| CTh (μm) | 240 ± 6 | 257 ± 5a,b | 240 ± 4 | 253 ± 5a,b | 220 ± 5 | 235 ± 6a | 0.05 | |

| BMaV (μm3) | 346 ± 18 | 624 ± 28a | 320 ± 12 | 629 ± 24a | 236 ± 9 | 475 ± 18a | 0.01 | |

a p < 0.05 versus base line (one way ANOVA with repeat measurements); p value for differences between periostin groups (one-way ANOVA with repeat measurements) (means ± S.E.).

b p < 0.05 versus non-stimulated (paired t test). p value for differences between periostin groups (one-way ANOVA with repeat measurements) (means ± S.E.).

FIGURE 2.

Effects of axial compression on tibia. Bars, mean ± S.E. measured after 2 weeks of axial compression in stimulated tibia (closed bars) or non-stimulated tibia (open bars) in Postn+/+, Postn+/−, and Postn−/− mice. A, trabecular bone microarchitecture of the proximal tibia. B, three-dimensional reconstruction images of the proximal tibia metaphysis cancellous bone. C, cortical bone microarchitecture of the midshaft tibia. D, two-dimensional reconstruction of the midshaft tibia. E, biomechanical properties of the cortical tibia measured by three-point bending. *, p < 0.05 paired t test compared with non-stimulated tibia within the periostin group; $, p < 0.05; $$, p < 0.01; $$$, p < 0.001, genotype effect between Postn+/+, Postn+/−, and Postn−/− mice by post hoc Fisher's PLSD following 2F-ANOVA. Shown are means ± S.E. S, stimulated tibia; NS, non-stimulated tibia.

Bone Turnover

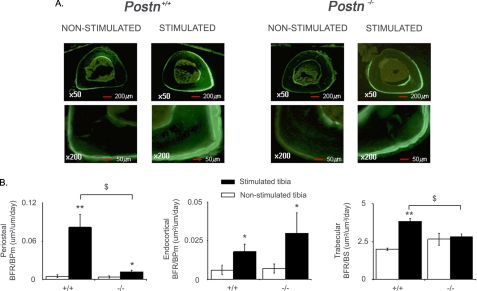

Bone histomorphometry confirmed that Postn+/+ mice had increased bone turnover in response to axial compression (Fig. 3 and supplemental Table S3). Hence, at the periosteum, loading increased the BFR 15.5-fold and the mineralization perimeter (MPm/BPm) 8.5-fold compared with the non-stimulated tibia in Postn+/+ mice (p < 0.01, Fig. 3 and supplemental Table S3). In contrast, compression did not significantly increase periosteal MPm/BPm in Postn−/− mice, whereas BFR/BPm increased 3.5-fold (p < 0.05). Thus, the periosteal BFR in the stimulated bone of Postn−/− mice remained significantly lower compared with Postn+/+ mice. Similarly, at the trabecular surfaces, axial compression increased MAR (+41.6%) and BFR (+92.4%) in Postn+/+ mice (p < 0.01 versus the non-stimulated tibia) (Fig. 3), whereas in Postn−/− mice, trabecular bone formation indices did not significantly differ between stimulated and non-stimulated bones (supplemental Table S3). Contrary to its prominent effects on periosteal and trabecular bone turnover, periostin appeared not to influence the bone forming indices at endocortical surfaces, which responded equally in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice.

FIGURE 3.

Bone remodeling at cortical bone surfaces in response to axial compression. A, immunofluorescent sections of midshaft tibia show cortical calcein labels on cortical surfaces of stimulated and non-stimulated bone in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice. B, BFR on the surfaces of bone. Bars, mean ± S.E. measured after 2 weeks of axial compression in stimulated tibia (closed bars) or non-stimulated tibia (open bars) in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, paired t test compared with non-stimulated tibia within the periostin group; $, p < 0.05, Postn+/+ versus Postn−/− mice by post hoc Fisher's PLSD following 2F-ANOVA. Shown are means ± S.E.

Effects of Axial Compression on Postn and Sost Expression

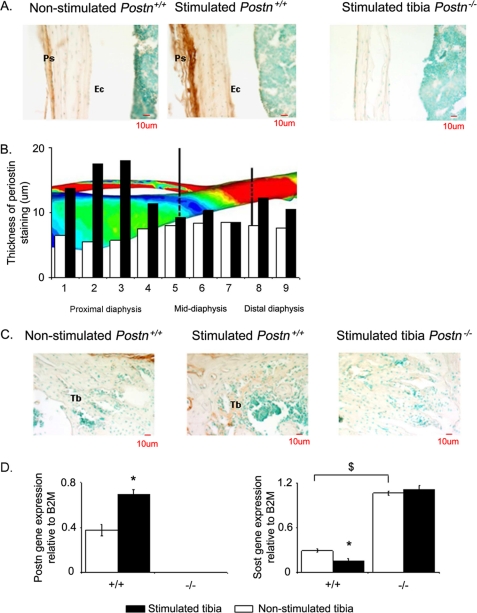

In order to clarify the molecular mechanisms by which periostin mediates the skeletal response to mechanical stimulation, we next examined the effects of axial compression on periostin protein expression in bone.

Immunohistochemistry revealed robustly elevated expression of the periostin in the periosteum 24 h after axial compression (Fig. 4A). The specificity of periostin expression was established by the lack of staining in Postn−/− bone sections. Periostin deposition along the bone axis indicates maximal expression within bone regions supporting the highest strain, such as the proximal diaphysis, which exhibited relatively large peak strains during axial compression (zones 1–4) (Fig. 4B) and the greatest increase in periostin staining (+56%) (Fig. 4B), whereas sections from the midshaft, which experience only relatively small peak strains during axial compression, only exhibited a modest increase in periostin staining (zones 5–7) (Fig. 4B). Consistent with previous reports (13), no periostin deposition was detected at endocortical surfaces in the proximal or distal diaphysis or in the midshaft region (Fig. 4A). Nevertheless, weak periostin staining was detected in cancellous bone after axial compression (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Periostin and Sost expression in bone response to mechanical strain. A, immunohistochemical analysis of periostin expression in longitudinal sections of the proximal tibia 24 h after mechanical stimulation or not. Note the brown staining of periostin in the periosteum (Ps) of wild type mice that increased with stimulation, whereas no staining is detectable at endocortical surfaces (Ec) or in Postn−/− mice. B, thickness of the periostin staining is shown in relation to the strain generated by axial compression along the tibia; high strain regions are green to red, and low strain regions are blue. Bars, mean measured after 24 h of axial compression in stimulated tibia (closed bars) or non-stimulated tibia (open bars) in Postn+/+ mice. C, immunohistochemical analysis of periostin expression in longitudinal section of the proximal metaphysis 24 h after mechanical stimulation or not. Note the soft staining of periostin in Tb compared with the periosteum bone (Fig. 5A). D, Postn and Sost gene expression levels in stimulated and non-stimulated tibia evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR analysis of RNA extracted from the tibia diaphysis. Bars, mean ± S.E. measured after 24 h of axial compression in stimulated tibia (closed bars) or non-stimulated tibia (open bars) in Postn+/+ mice. *, p < 0.05, paired t test compared with non-stimulated tibia within periostin group. $, p < 0.05, Postn+/+ versus Postn−/− mice by post hoc Fisher's PLSD following 2F-ANOVA. Data are presented as means ± S.E. of n = 4 mice in each genotype.

We further evaluated the time course of Postn and Sost mRNA expression following axial compression. A single regimen of axial compression (12 N and 0.1 Hz for 7 min) of the tibia induced a rapid (6 h), 2.2-fold increase of Postn expression (relative abundance: 0.42 ± 0.1 versus 0.13 ± 0.04, p < 0.05 in loaded versus non-loaded; data not shown). After 24 h, increased Postn expression was sustained and accompanied by a significant 50% decrease of Sost expression in Postn+/+ mice but not in Postn−/− mice. In the latter, Sost expression was significantly higher than Postn+/+ mice in both the non-loaded and loaded tibia (Fig. 4D). These data suggest that stimulation of Postn and inhibition of Sost expression in response to mechanical loading are temporally related.

Skeletal Response to Axial Compression Combined with Sclerostin-blocking Antibodies

To directly evaluate the role of sclerostin in the molecular mechanisms by which periostin mediates the skeletal response to mechanical stimulation, we next examined if the injection of Sost-Ab into Postn−/− mice could rescue their bone phenotypes and restore their responses to loading.

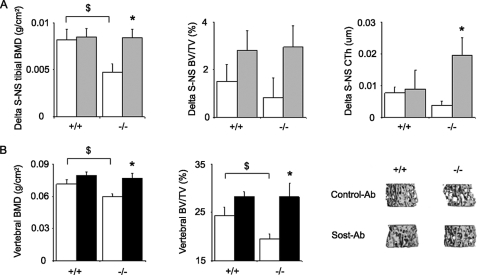

Bone Mineral Density and Architecture

Again, in control Ab-treated mice, tibia BMD gain in response to axial compression was significantly lower in Postn−/− mice compared with Postn+/+ mice (+6.8% versus +20.7%, p < 0.05). In Postn−/− mice receiving Sost-Ab, the BMD gain in the stimulated tibia was fully rescued (+34.8%) (i.e. not different from the Postn+/+ mice receiving Sost-Ab) (+26%). The cortical response to axial compression was also restored by Sost-Ab in the Postn−/− mice, as shown by their higher cortical thickness in the stimulated versus the non-stimulated tibia (+6.9% versus +1.5% (p < 0.05) in the group receiving control Ab) (Fig. 5A). Meanwhile, in Postn+/+ mice, the administration Sost-Ab concomitant to axial compression did not significantly improve the anabolic effect of compression alone, which is consistent with the Sost-inhibitory effects of mechanical loading in normal mice. A similar trend was observed for BV/TV of the trabecular bone compartment (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of Sost-Ab on tibia response to axial compression. A, differences in tibia BMD, trabecular bone volume, and cortical thickness between the stimulated and the non-stimulated tibia for the BMD in mice receiving Sost-Ab (gray bars) or control Ab (open bars). B, bone mineral density and three-dimensional trabecular bone microarchitecture of the vertebrae in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice receiving Sost-Ab (closed bars) or control Ab (open bars). Bars, mean ± S.E. $, p < 0.05, Postn+/+ versus Postn−/− mice; *, Sost-Ab versus control Ab by post hoc Fisher's PLSD following 2F-ANOVA. Shown are means ± S.E.

Of note, the lower vertebral BMD and BV/TV in Postn−/− mice compared with Postn+/+ mice was also rescued by short term administration of Sost-Ab (Fig. 5B), further demonstrating that the higher expression of Sost was in part responsible for the lower bone mass of Postn-deficient mice.

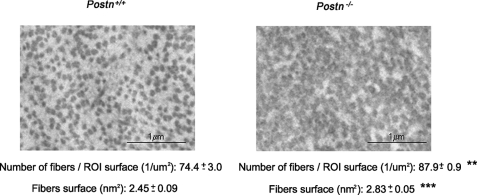

Collagen Structure in Postn−/− Mice

Because it has been reported that the size and structure of collagen fibrils is altered in Postn−/− alveolar bone, we next hypothesized that poor mechanotransduction properties in the cortical bone of Postn-deficient mice could reflect the altered structure of the bone matrix at this site. For this purpose, we analyzed collagen size and shape at the periosteum by electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6, the cortical bone of Postn−/− mice was characterized by more abundant and larger collagen fibrils compared with Postn+/+ mice (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Characterization of the collagen fibril at the periosteum in Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice. Electron microscopy shows cross-sectional collagen fibril in 12-week-old Postn+/+ mice on the left and in 12-week-old Postn−/− mice on the right. Postn−/− mice shows abundant and bigger collagen fibrils. Means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001, unpaired t test compared Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice. ROI, region of interest.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of our study was to elucidate the in vivo role of periostin in the skeletal response to mechanical loading. The loss of Postn in mice resulted in altered cancellous bone microarchitecture (lower BV/TV and TbN and higher TbSp and SMI), reduced cortical bone volume, and decreased bending mechanical properties (bone strength). We specifically demonstrate that periostin regulates the skeletal response to mechanical signals by mediating Sost inhibition. These results confirm and expand the important role of periostin in the determination of bone mass and structure (13) and demonstrate the influence of Postn in bone turnover. More broadly, they emphasize the role of periostin in transducing mechanical signals, as previously shown in other tissues, including the periodontal ligament and heart valves (5, 7, 9, 15, 40, 41).

We provide several lines of evidence indicating that periostin expression is essential for the down-regulation of Sost. First, Postn mRNA and protein expression increased by axial compression prior to the inhibition of Sost expression in the same bone compartment, indicating that these events are both spatially and temporally related. Second, in Postn−/− mice, Sost expression was increased and was not inhibited following axial compression. Third, administration of a Sost-Ab to Postn−/− mice improved their low bone mass and trabecular bone volume in vertebrae, a non-loaded site, and rescued the biomechanical response of the tibia to axial compression. To potentially explain the absence of Sost inhibition in Postn−/− mice, two major hypotheses are suggested. First, the absence of Postn could alter the structure of the bone matrix and therefore impair its mechanotransduction properties. Altered shape, structure, and disorganization of type I collagen fibers had previously been reported in the alveolar bone of Postn−/− mice (14). We now confirm similar alterations in type I collagen fibers of the Postn−/− periosteal bone by electron microscopy. Second, periostin activates the integrin signaling pathways (Akt/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) (42, 43), which we also found in UMR-106 osteoblast-like cells (data not shown). Integrins are known to mediate osteocyte response to mechanical stimulation (44, 45), and it is possible therefore that periostin contributes to Sost inhibition by co-activating integrin signaling in these cells. In addition, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling may influence Wnt-LRP5 signaling by inhibiting GSK3 kinase and releasing β-catenin from its inhibitory complex (46–48). It is therefore also possible that periostin directly stimulates canonical signaling pathways for bone formation via integrin receptors.

The presence of shorter long bones in Postn-/- mice suggests a disruption of the cartilaginous growth plate (13). Moreover, due to their periodontal alterations and ensuing difficulties with feeding, these mice are known to mature slowly and to present a deficit in body weight. Although we attempted to improve their feeding and growth rate by giving them a soft diet from birth, Postn−/− mice still exhibited a slower growth rate with a continuous increase of BV/TV up to 16–18 weeks of age (i.e. longer than wild type mice). Nevertheless, Postn−/− mice never catch up the higher bone mass of Postn+/+ mice. In any case, a prolonged period of bone mass growth in Postn−/− mice could only favor, rather than inhibit, their response to mechanical stimulation. Therefore, the slight growth delay in Postn−/− mice is very unlikely to explain their significant lack of responses to mechanical stimulation.

Pharmacological studies have previously suggested that periostin may play a role in bone formation. Horiuchi et al. (15) observed a dose-dependent response of periostin expression to TGF-β stimulation in primary osteoblast cells. PTH was also shown to up-regulate Postn, together with other cell adhesion proteins, concomitant to its stimulation of bone formation on histomorphometric analyses of rat bones (49, 50). In addition, in 6-week-old rats, Postn overexpression increased bone formation and bone mass, as evaluated by microCT and histomorphometry (51). In vitro, overexpression of Postn results in a significant increase in primary osteoblast cell proliferation and differentiation (51). Conversely, deletion of Postn induces a defect in the attachment of bone cells, which affects their differentiation and mineralization processes (16). Our results further indicate that, although osteoblast numbers and bone formation indices are not notably prominently altered in mice lacking Postn, bone turnover (as evaluated by BFR) in response to loading is clearly diminished in the absence of periostin, particularly within the cortical compartment.

Although we did not observe clear differences of osteoblast number or surface between Postn+/+ and Postn−/− mice subjected to physical activity, activity of osteoblast (Tb MAR and Tb BFR) was significantly higher in Postn+/+ mice at the trabecular level. This is not unexpected, because osteoblast function, rather than proliferation, is primarily affected by exercise (52). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that histomorphometry performed at the end of the experiment (5 weeks after the first training session) could have missed the anabolic effects of exercise that may have occurred earlier (53).

Mechanical loading (axial compression or exercise) is an effective way to increase bone mass and prevent bone loss, and it may reduce fracture risk (54–56). Mechanical properties of long bones are more profoundly affected by modifications of the periosteal surface than the endocortical compartment (57–59). Indeed, mechanical loading induces an increase in bone strength by targeting new bone formation to skeletal surfaces experiencing the largest mechanical strain (i.e. the periosteum) (24, 27, 60). Interestingly, periostin is preferentially expressed in the periosteum rather than in the endocortical region, and selective stimulation of periostin expression in the periosteum as well as greater increases of bone formation indices in the periosteal compartment both occurred in response to mechanical stimulation. Our current results therefore suggest that periostin may serve as a molecular conduit to concentrate biomechanical signals to the outer surfaces of bone (i.e. where they are most needed). Of note, the skeletal phenotype of Postn haploinsufficient mice (Postn+/− mice) did not significantly differ from wild type mice; nor was their response to direct axial compression affected. In contrast, the skeletal response of Postn+/− mice to moderate physical activity was impaired, as seen in Postn−/− mice. This may suggest that the level of periostin expression modulates the sensitivity of the mechanostat (i.e. that periostin may be able to decrease the threshold for a bone biomechanical response). Thus, in response to high mechanical loads (axial compression), a low level of periostin expression (as in haploinsufficient mice) was necessary and sufficient to induce a biomechanical response, whereas with moderate mechanical stimuli (i.e. during exercise), even a partial deficiency of periostin resulted in a diminished skeletal response. Another possible explanation is that low periostin levels may disrupt the myotendinous junction, which is one of the important mechanisms by which exercise-induced strain can be transmitted to the bone (61). This hypothesis is further supported by the recent findings that periostin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis, whereas in the absence of Postn, the biomechanical properties of connective tissues, such as the tendon, are affected (9).

Taken together, these data suggest a role for periostin in mediating bone formation in response to mechanical loading. Specifically, mechanical loading increases periostin expression, which is necessary to inhibit Sost expression and thereby to up-regulate osteoblast functions. In the absence of periostin, bone formation is impaired, and mechanical loading is unable to effectively improve bone structure and strength, unless sclerostin protein is antagonized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Goldie Lin for histological assistance and Dr. Tara Brennan for editorial assistance. We also thank Dr. Michaela Kneissel (Novartis, AG, Basel, Switzerland) for providing the sclerostin-blocking antibodies and for assistance in designing these experiments. We thank Fanny Cavat for technical assistance and the Pôle Facultaire de Microscopie ultrastructural at the Geneva Medical Faculty for access to transmission electron microscopy equipment.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL060714 and R01HL092508 (to S. J. C.) and T32 HL079995 (to K. S.). These studies were also supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grants 3100A0-116633/1 (to S. L. F.) and 310030-120280 (to M. F.), by the seventh Framework program of the European Community (HEALTH-F2–2008-201099) (to S. L. F.), the Riley Children's Foundation (to S. J. C.), and the Indiana University Department of Pediatrics/Cardiology (to S. J. C.). This work was further supported by a grant from the “Société Francaise de Rhumatologie” and the GRIO (to N. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

- Sost-Ab

- sclerostin-blocking antibody

- Ab

- antibody

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- 1F-ANOVA

- one-factor ANOVA

- 2F-ANOVA

- two-factor ANOVA

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- microCT

- microcomputed tomography

- N

- newton

- PLSD

- protected least squares difference

- BV

- bone volume

- TV

- total volume

- TbTH

- trabecular thickness

- TbN

- trabecular number

- Tb

- trabecular

- Conn density

- connectivity density

- SMI

- structural model index

- CtTV

- cortical tissue volume

- CtBV

- cortical tissue bone volume

- BMaV

- bone marrow volume

- CtTh

- average cortical width

- MAR

- mineral apposition rate

- SLS

- single-labeled surface

- BS

- bone surface

- dLS

- double-labeled surface

- MS

- mineralizing surface

- BFR

- bone formation rate

- TbSp

- separation between trabeculae

- MPm

- mineralization perimeter

- BPm

- bone perimeter.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takeshita S., Kikuno R., Tezuka K., Amann E. (1993) Biochem. J. 294, 271–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gillan L., Matei D., Fishman D. A., Gerbin C. S., Karlan B. Y., Chang D. D. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 5358–5364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimazaki M., Nakamura K., Kii I., Kashima T., Amizuka N., Li M., Saito M., Fukuda K., Nishiyama T., Kitajima S., Saga Y., Fukayama M., Sata M., Kudo A. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 295–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao S., Ouyang G., Bai X., Huang Z., Ma C., Liu M., Shao R., Anderson R. M., Rich J. N., Wang X. F. (2004) Cancer Cell 5, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsuragi N., Morishita R., Nakamura N., Ochiai T., Taniyama Y., Hasegawa Y., Kawashima K., Kaneda Y., Ogihara T., Sugimura K. (2004) Circulation 110, 1806–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorn G. W., 2nd (2007) N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1552–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snider P., Hinton R. B., Moreno-Rodriguez R. A., Wang J., Rogers R., Lindsley A., Li F., Ingram D. A., Menick D., Field L., Firulli A. B., Molkentin J. D., Markwald R., Conway S. J. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 752–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litvin J., Blagg A., Mu A., Matiwala S., Montgomery M., Berretta R., Houser S., Margulies K. (2006) Cardiovasc. Pathol. 15, 24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norris R. A., Damon B., Mironov V., Kasyanov V., Ramamurthi A., Moreno-Rodriguez R., Trusk T., Potts J. D., Goodwin R. L., Davis J., Hoffman S., Wen X., Sugi Y., Kern C. B., Mjaatvedt C. H., Turner D. K., Oka T., Conway S. J., Molkentin J. D., Forgacs G., Markwald R. R. (2007) J. Cell. Biochem. 101, 695–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilde J., Yokozeki M., Terai K., Kudo A., Moriyama K. (2003) Cell Tissue Res. 312, 345–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rios H. F., Ma D., Xie Y., Giannobile W. V., Bonewald L. F., Conway S. J., Feng J. Q. (2008) J. Periodontol. 79, 1480–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Afanador E., Yokozeki M., Oba Y., Kitase Y., Takahashi T., Kudo A., Moriyama K. (2005) Arch. Oral Biol. 50, 1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rios H., Koushik S. V., Wang H., Wang J., Zhou H. M., Lindsley A., Rogers R., Chen Z., Maeda M., Kruzynska-Frejtag A., Feng J. Q., Conway S. J. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 11131–11144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kii I., Amizuka N., Minqi L., Kitajima S., Saga Y., Kudo A. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 342, 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horiuchi K., Amizuka N., Takeshita S., Takamatsu H., Katsuura M., Ozawa H., Toyama Y., Bonewald L. F., Kudo A. (1999) J. Bone Miner. Res. 14, 1239–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litvin J., Selim A. H., Montgomery M. O., Lehmann K., Rico M. C., Devlin H., Bednarik D. P., Safadi F. F. (2004) J. Cell. Biochem. 92, 1044–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogita M., Rached M. T., Dworakowski E., Bilezikian J. P., Kousteni S. (2008) Endocrinology 149, 5713–5723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakazawa T., Nakajima A., Seki N., Okawa A., Kato M., Moriya H., Amizuka N., Einhorn T. A., Yamazaki M. (2004) J. Orthop. Res. 22, 520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto J., Takeda T., Ichimura S. (1998) J. Orthop. Sci. 3, 257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwamoto J., Yeh J. K., Aloia J. F. (1999) Bone 24, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnet N., Laroche N., Beaupied H., Vico L., Dolleans E., Benhamou C. L., Courteix D. (2007) J. Appl. Physiol. 103, 524–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robling A. G., Burr D. B., Turner C. H. (2001) J Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 1, 249–262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K. C., Maxwell A., Lanyon L. E. (2002) Bone 31, 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza R. L., Pitsillides A. A., Lanyon L. E., Skerry T. M., Chenu C. (2005) J. Bone Miner Res. 20, 2159–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robling A. G., Li J., Shultz K. L., Beamer W. G., Turner C. H. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 324–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robling A. G., Niziolek P. J., Baldridge L. A., Condon K. W., Allen M. R., Alam I., Mantila S. M., Gluhak-Heinrich J., Bellido T. M., Harris S. E., Turner C. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5866–5875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawakami K., Robling A. G., Ai M., Pitner N. D., Liu D., Warden S. J., Li J., Maye P., Rowe D. W., Duncan R. L., Warman M. L., Turner C. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23698–23711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Q. Y. (2008) International Bone and Mineral Workshops, Davos, SwitzerlandMarch 9–11, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadelmann V. A., Hocke J., Verhelle J., Forster V., Merlini F., Terrier A., Pioletti D. P. (2008) Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 12, 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X., Ominsky M. S., Warmington K. S., Morony S., Gong J., Cao J., Gao Y., Shalhoub V., Tipton B., Haldankar R., Chen Q., Winters A., Boone T., Geng Z., Niu Q. T., Ke H. Z., Kostenuik P. J., Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L., Paszty C. (2009) J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 578–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narkar V. A., Downes M., Yu R. T., Embler E., Wang Y. X., Banayo E., Mihaylova M. M., Nelson M. C., Zou Y., Juguilon H., Kang H., Shaw R. J., Evans R. M. (2008) Cell 134, 405–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iida-Klein A., Lu S. S., Yokoyama K., Dempster D. W., Nieves J. W., Lindsay R. (2003) J. Clin. Densitom. 6, 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waarsing J. H., Day J. S., van der Linden J. C., Ederveen A. G., Spanjers C., De Clerck N., Sasov A., Verhaar J. A., Weinans H. (2004) Bone 34, 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waarsing J. H., Day J. S., Weinans H. (2002) The IXth Congress of the International Society of Bone Morphometry, Edingburgh, UK, April, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouxsein M. L., Pierroz D. D., Glatt V., Goddard D. S., Cavat F., Rizzoli R., Ferrari S. L. (2005) J. Bone Miner Res. 20, 635–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hildebrand T., Ruegsegger P. (1997) J. Microsc. 185, 67–75 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parfitt A. M., Drezner M. K., Glorieux F. H., Kanis J. A., Malluche H., Meunier P. J., Ott S. M., Recker R. R. (1987) J. Bone Miner. Res. 2, 595–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foti M., Carpentier J. L., Aiken C., Trono D., Lew D. P., Krause K. H. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1377–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner C. H., Burr D. B. (1993) Bone 14, 595–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Litvin J., Zhu S., Norris R., Markwald R. (2005) Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell Evol. Biol. 287, 1205–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norris R. A., Moreno-Rodriguez R. A., Sugi Y., Hoffman S., Amos J., Hart M. M., Potts J. D., Goodwin R. L., Markwald R. R. (2008) Dev. Biol. 316, 200–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruan K., Bao S., Ouyang G. (2009) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 66, 2219–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashima T. G., Nishiyama T., Shimazu K., Shimazaki M., Kii I., Grigoriadis A. E., Fukayama M., Kudo A. (2009) Hum. Pathol. 40, 226–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyauchi A., Gotoh M., Kamioka H., Notoya K., Sekiya H., Takagi Y., Yoshimoto Y., Ishikawa H., Chihara K., Takano-Yamamoto T., Fujita T., Mikuni-Takagaki Y. (2006) J. Bone Miner. Metab. 24, 498–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips J. A., Almeida E. A., Hill E. L., Aguirre J. I., Rivera M. F., Nachbandi I., Wronski T. J., van der Meulen M. C., Globus R. K. (2008) Matrix Biol. 27, 609–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baril P., Gangeswaran R., Mahon P. C., Caulee K., Kocher H. M., Harada T., Zhu M., Kalthoff H., Crnogorac-Jurcevic T., Lemoine N. R. (2007) Oncogene 26, 2082–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armstrong V. J., Muzylak M., Sunters A., Zaman G., Saxon L. K., Price J. S., Lanyon L. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20715–20727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He X., Semenov M., Tamai K., Zeng X. (2004) Development 131, 1663–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onyia J. E., Helvering L. M., Gelbert L., Wei T., Huang S., Chen P., Dow E. R., Maran A., Zhang M., Lotinun S., Lin X., Halladay D. L., Miles R. R., Kulkarni N. H., Ambrose E. M., Ma Y. L., Frolik C. A., Sato M., Bryant H. U., Turner R. T. (2005) J. Cell. Biochem. 95, 403–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X., Liu H., Qin L., Tamasi J., Bergenstock M., Shapses S., Feyen J. H., Notterman D. A., Partridge N. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33086–33097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu S., Barbe M. F., Liu C., Hadjiargyrou M., Popoff S. N., Rani S., Safadi F. F., Litvin J. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 218, 584–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barengolts E. I., Lathon P. V., Curry D. J., Kukreja S. C. (1994) Bone Miner. 26, 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bourrin S., Palle S., Pupier R., Vico L., Alexandre C. (1995) J. Bone Miner. Res. 10, 1745–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zehnacker C. H., Bemis-Dougherty A. (2007) J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 30, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinaki M. (2007) Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 18, 593–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engelke K., Kemmler W., Lauber D., Beeskow C., Pintag R., Kalender W. A. (2006) Osteoporos. Int. 17, 133–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferretti J. L., Frost H. M., Gasser J. A., High W. B., Jee W. S., Jerome C., Mosekilde L., Thompson D. D. (1995) Calcif. Tissue Int. 57, 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seeman E., Delmas P. D. (2006) N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 2250–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seeman E. (2002) Lancet 359, 1841–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chambers T. J., Evans M., Gardner T. N., Turner-Smith A., Chow J. W. (1993) Bone Miner. 20, 167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frost H. M. (1987) Anat. Rec. 219, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]