Abstract

Laulimalide is a structurally unique 20-membered marine macrolide displaying microtubule stabilizing activity similar to that of paclitaxel and the epothilones. The use of atom economical transformations such as a rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization to form the endocyclic dihydropyran, a dinuclear zinc-catalyzed asymmetric glycolate aldol to prepare the syn 1,2-diol and an intramolecular ruthenium-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling to build the macrocycle enabled us to synthesize laulimalide via an efficient and convergent pathway. The designed synthetic route also allowed us to prepare an analogue of the natural product that possesses significant cytotoxic activity.

Laulimalide (1), also called fijianolide B, is a structurally unique 20-membered marine macrolide isolated from several sources of marine sponges, such as Cacospongia mycofijiensis, Hyattella sp. and Fasciospongia rimosa.1 Initially, it was shown that laulimalide displays potent cytotoxicity towards numerous NCI cell lines,1b however, it did not attract the attention of synthetic chemists until Mooberry and coworkers discovered that laulimalide displays microtubule stabilizing activity similar to that of paclitaxel and the epothilones.2 Both its unique pharmaceutical profile and challenging chemical architecture has attracted considerable interest, leading to numerous attempts and several successful syntheses of both the naturally occurring compound and some analogs.3 These approaches have underscored several unique structural features that must be addressed via the development of new efficient and atom economical transformations.4

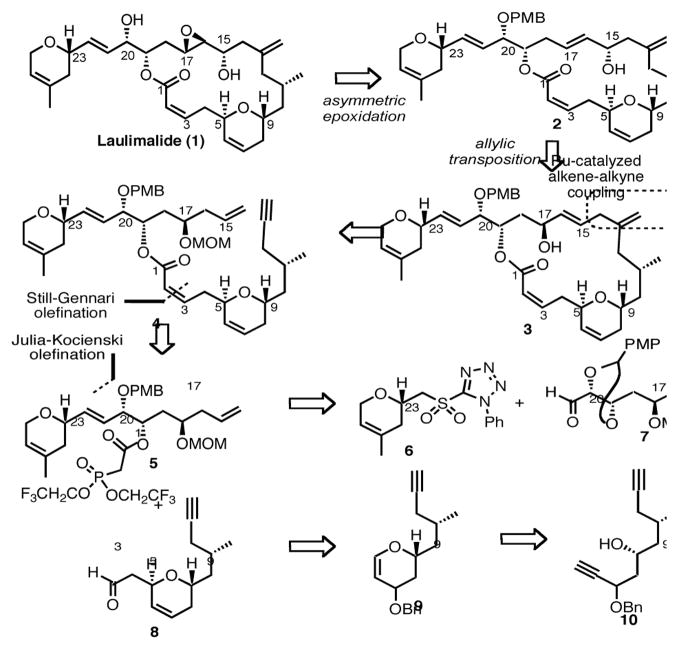

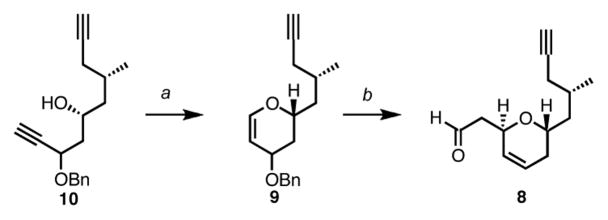

With the aim to further illustrate the inherent versatility of the alkyne functional group in the context of complex natural product synthesis, we specifically intended to test the applicability of our ruthenium-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling to construct the laulimalide macrocycle. As such, our retrosynthetic analysis for laulimalide is based on the notion that the natural product could be formed from the 1,4-diene 3, which we believe could be converted into allylic alcohol 2 via a stereospecific 1,3-allylic transposition (Scheme 1). Alternatively, a diastereoselective epoxidation of allylic alcohol 3 followed by a Payne rearrangement5 could also provide access to laulimalide. The 1,4-diene 3 would arise from an intramolecular ruthenium-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling of enyne 4,6 in turn accessed from a Still-Gennari olefination7 between two synthons of similar complexity: phosphonate 5 and aldehyde 8. The northern fragment 5 could be generated via a Julia-Kocieński olefination8 between phenyltetrazole sulfone 6 and aldehyde 7. In addition, a rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization applied to compound 10 would produce dihydropyran 9, precursor of the southern fragment 8.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of laulimalide

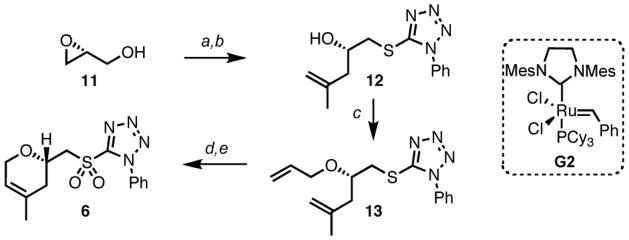

A protecting group free strategy allowed us to efficiently synthesize the required sulfone 6, whose assembly began from (R)-glycidol 11 (Scheme 2). Conversion of the latter into the corresponding epoxysulfide followed by epoxide opening with isopropenylmagnesium bromide, in the presence of copper iodide, led to the corresponding secondary alcohol 12, which needed to be transformed into diene 13. While attempts at allylation under basic or acidic conditions were ineffective, addition of the zinc alkoxide of alcohol 12 to allylacetate, in the presence of a catalytic amount of Pd(0), successfully resulted in the smooth formation of the desired allylated compound 13.9 Molybdenum-catalyzed oxidation of the sulfide into the corresponding sulfone followed by a ring closing metathesis using the second generation Grubbs catalyst G2 ultimately provided the desired dihydropyran 6, which constitutes the side chain of laulimalide.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the dihydropyran side chaina.

aConditions: (a) DEAD, PPh3, 1-phenyl-1H-tetrazole-5-thiol, THF, 82%; (b) CuI, propenylmagnesium bromide, THF, 99%; (c) Et2Zn, 10 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 25 mol% PPh3, allylacetate, THF, 62% (76% brsm); (d) 15 mol% Mo7O24(NH4)6·4H2O, H2O2, EtOH, 83%; (e) 3 mol% G2, CH2Cl2 (c 0.015 M), 95%.

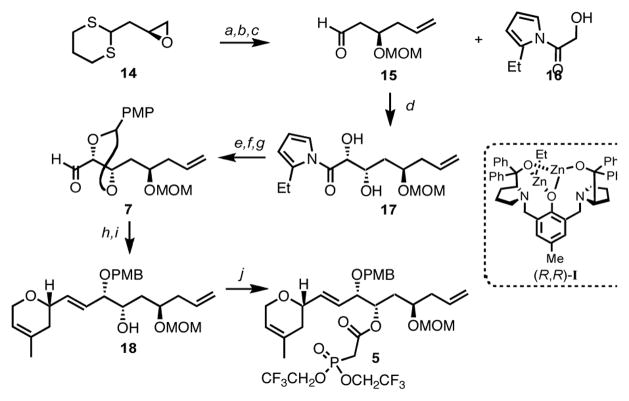

Next, our attention turned towards the preparation of the syn 1,2-diol 7, whose synthesis would hinge on the development of a novel direct asymmetric aldol-type reaction promoted by dinuclear zinc catalyst (R,R)-I using a donor partner at the carboxylic acid oxidation state (Scheme 3).10 Thus, the β-hydroxyaldehyde 15, prepared from the known epoxide 14, would be transformed into syn diol 7 by using the above-mentioned methodology. As we needed to have access to the aldehyde functionality present in compound 7, we decided to examine the utilization of hydroxy acylpyrroles as donors.11,12 Extensive exploration of this transformation led us to consider the use of hydroxy 2-ethyl acylpyrrole 16, in the presence of 15 mol% of the dinuclear zinc catalyst (R,R)-I, which gratifyingly furnished the desired syn 1,2-diol 17 with a 10:1 dr. Subsequent protection of the resulting diol as a PMP-acetal, followed by a reduction/oxidation sequence provided the desired aldehyde 7. With access to both sulfone 6 and aldehyde 7, the envisaged Julia-Kocieński olefination could be implemented and successfully furnished, after selective opening of the PMP-acetal with DIBAL-H,13 the desired alcohol 18 as a single (E)-configured geometric isomer. Esterification between the latter compound and bis-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)phosphonoacetic acid under Yamaguchi conditions proceeded to give the targeted β-ketophosphonate 5 in near quantitative yield.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the northern fragment 5a.

aConditions: (a) H2C=CHMgBr, CuI, THF, 95%; (b) MOMCl, iPr2EtN, CH2Cl2, 97%; (c) MeI, CaCO3, MeCN/H2O (9:1), 85%; (d) 15 mol% (R,R)-I, THF, 53%, dr = 10:1; (e) p-MeOPhCH(OMe)2, 10-CSA, CH2Cl2, 81%; (f) NaBH4, THF, 86%; (g) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2; (h) 6, LiHMDS, DMF/HMPA (3:1), 64% over 2 steps; (i) DIBAL-H, CH2Cl2, 61%; (j) (CF3CH2O)2P(O)CH2CO2H, 2,4,6-trichlorobenzoylchloride, i-Pr2EtN, THF then DMAP, PhH, 99%.

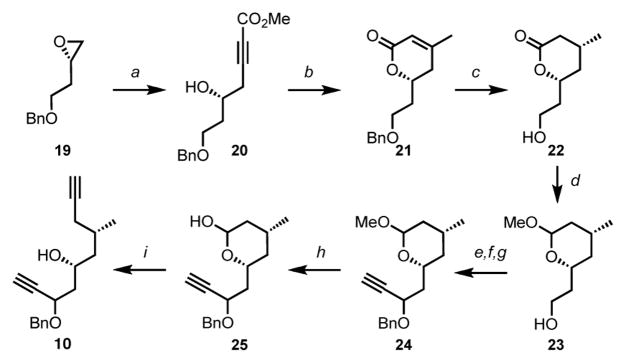

The preparation of the targeted diyne 10 commenced from the known oxirane 19 derived from D-aspartic acid (Scheme 4).14 Regioselective opening of epoxide 19 with the lithium salt of methyl propiolate furnished homopropargylic alcohol 20, which in turn underwent a stereo- and regioselective cis-addition of lithium dimethylcuprate followed by acid-catalyzed lactonization to afford α,β-unsaturated lactone 21. Diastereoselective hydrogenation15 and concomitant benzyl deprotection eventually gave rise to the saturated lactone 22 as a single stereoisomer. Exposure of the latter to DIBAL-H and subsequent acetalization provided the mixed acetal 23. Oxidation of the primary alcohol followed by Grignard addition and subsequent benzylation yielded propargylic alcohol 24. Hydrolysis of acetal 24 under acidic conditions produced hemiketal 25, allowing for the installation of another alkyne functionality. To this end, hemiketal 25 was exposed to the Ohira-Bestmann reagent to furnish the required diyne 10.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of the diyne precursor 10a.

aConditions: (a) Methyl propiolate, n-BuLi, BF3·Et2O, THF, 93%; (b) CuI, MeLi, THF then AcOH, PhH, 94%; (c) Pd(OH)2, H2, EtOAc, 97%; (d) DIBAL-H, CH2Cl2 then Dowex 50W × 8, MeOH, 99%; (e) TEMPO, NaOCl, KBr, NaHCO3, CH2Cl2/H2O, 97%; (f) Ethynylmagnesium bromide, THF, 77%; (g) NaH, BnBr, DMF, 96%; (h) AcOH, H2SO4, H2O, 82%; (i) Dimethyl-1-diazo-2-oxopropylphosphonate, K2CO3, MeOH, 57% (69% brsm).

Having established a robust route to prepare diyne 10, we then turned our attention to the subsequent rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization step.16 The presence of two alkyne functional groups in the substrate raised an interesting question as to the chemoselectivity under these conditions. Based on previous studies in our group, we were confident that the six-membered ring formation would be favored over the seven-membered ring formation but it remained still uncertain whether the additional alkyne functionality would play any role in the reaction. Gratifyingly, exposure of bis-homopropargylic alcohol 10 to 5 mol% of Rh(COD)Cl2, in the presence of an electron poor bidentate phosphine ligand successfully afforded the desired dihydropyran in satisfying yield. Noteworthy, none of the 7-membered ring product could be detected via 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. The vinylogous acetal 9 thus obtained was ultimately activated under acidic conditions in the presence of (tert-butyldimethylsilylvinyl)ether, to produce the desired trans-disubstituted dihydropyran 8 almost exclusively (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Synthesis of the southern fragment 8a.

aConditions: (a) 5 mol% [Rh(COD)Cl]2, 10 mol% [m-F(C6H6)]2PCH2CH2P[m-F(C6H6)]2, DMF, 55%; (b) CH2=CHOTBS, Montmorillonite K-10, CH2Cl2, 82%.

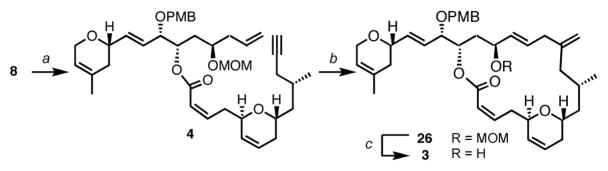

With both fragments 5 and 8 in hand, the coupling reaction could be implemented. Thus, condensation of the potassium salt of phosphonate 5 onto aldehyde 8, in the presence of 18-crown-6 provided the desired alkenoate 4 as a 1:5 mixture of (E/Z)-isomers, which were easily separable by flash chromatography on silica gel (Scheme 6). Completion of enyne 4 set the stage to probe the challenging intramolecular alkene-alkyne coupling.17 To this end, exposing enyne 4 to 5 mol% of [CpRu(CH3CN)3]PF6, in acetone at 50 °C, proceeded with exceptional efficiency to furnish the desired 1,4-diene 26 as a single regioisomer and in 99% yield! Strikingly, only 15 minutes were required to perform this macrocycloisomerization with complete stereo-, chemo- and regioselectivity. Noteworthy, no isomerization of the (Z)-alkenoate could be detected. Deprotection of the MOM group under mild acidic conditions ultimately afforded the desired allylic alcohol 3.

Scheme 6. Intramolecular Ru-catalyzed alkene-alkyne couplinga.

aConditions: (a) 5, KHMDS, 18-crown-6, THF, E/Z = 1/5, 62% (50% isolated Z-isomer); (b) 5 mol% [CpRu(CH3CN)3]PF6, acetone (c 0.001 M), 50 °C, 15 min, 99%; (c) PPTS, tert-BuOH, 66%.

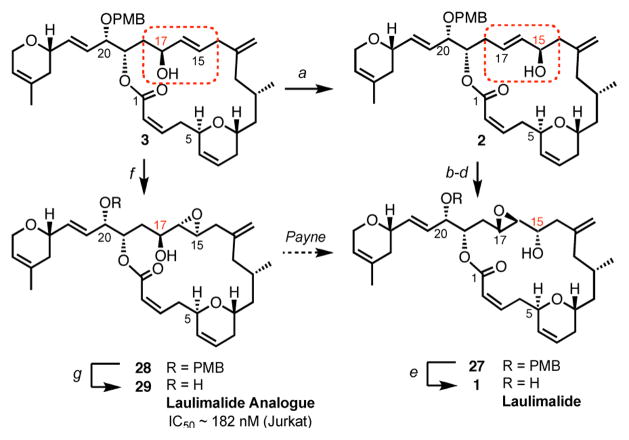

Upon completion of the targeted 1,4 diene 3, we were in a favorable position to investigate the equally ambitious selective 1,3-allylic transposition, in order to obtain the rearranged allylic alcohol 2, precursor of laulimalide. There are a several known chemical transformations that can, in principle, provide the allylic alcohol 2 from its regioisomer 3, formally through a 1,3-allylic rearrangement. We first envisioned that conversion of allylic alcohol 3 into an allylic selenoxide would set the stage for a [2,3]-sigmatropic shift, leading to the desired rearranged allylic alcohol epimeric of 2 at C15.18 However, using standard Mitsunobu-type conditions19 allylic alcohol 3 could not be converted into the corresponding selenide. Alternatively, a diastereoselective epoxidation of allylic alcohol 3 followed by a Payne rearrangement5 could potentially allow the formation of the rearranged epoxy alcohol 27, a precursor of laulimalide. This approach was regrettably hampered by an intramolecular attack of the C17 hydroxyl group onto the proximal ester under basic conditions, resulting in the formation of the corresponding ring contracted lactone. Being unable to perform the epoxide translocation, another strategy which would allow us to obtain the natural product laulimalide from our intermediate 3 needed to be devised. It has been previously shown that the isomerization of allylic alcohols via 1,3-transposition of a hydroxy group can be catalyzed by a number of high oxidation state transition metal oxo complexes, such as vanadium, tungsten, molybdenum or rhenium.20 To our delight, the utilization of the rhenium oxo catalysis conditions developed by Osborn et al.,21 which involve the highly active triphenylsilyl perrhenate catalyst (O3ReOSiPh3), resulted in the clean formation of the rearranged product 2, with complete retention of configuration (Scheme 7). We found that using one equivalent of the rhenium catalyst for 5 min at −50 °C in Et2O was optimal in obtaining the rearranged allylic product 2 (78% isolated yield), easily separable by flash column chromatography on silica gel from the remaining starting material 3 (97% yield brsm). Subsequent inversion of the C15 stereogenic center following an oxidation/CBS-reduction sequence allowed us to obtain the epimeric allylic alcohol of 2 at C15. Epoxidation of the latter compound using Sharpless conditions22 followed by DDQ deprotection ultimately furnished laulimalide, whose spectral and physical data were in total agreement with those reported for the natural product.1,23

Scheme 7. Completion of the synthesis of laulimalide and a potent analoguea.

aConditions: (a) O3ReOSiPh3, Et2O, 5 min, 78% (97% brsm); (b) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2; (c) (R)-Me-CBS, BH3·THF, THF, 93% over 2 steps; (d) (+)-DET, Ti(i-OPr)4, TBHP, 4 Å MS, CH2Cl2, 88%; (e) DDQ, CH2Cl2/pH7 buffer/tert-BuOH, 89%; (f) (+)-DET, Ti(i-OPr)4, TBHP, 4 Å MS, CH2Cl2, 86%; (e) DDQ, CH2Cl2/pH7 buffer/tert-BuOH, 71%.

It has been well established that under mildly acidic conditions laulimalide undergoes furan formation through a SN2-type attack of the hydroxy group situated on the lateral chain at C20 onto the epoxide at C17, leading to the so-called significantly less active isolaulimalide (IC50 = 20 000 nM).1b Therefore, there is undoubtedly a need to prepare laulimalide analogues designed in a such a fashion that would prevent furan formation while at the same time exhibiting similar or improved activity as compared to the natural product. With compound 3 in hand, a diastereoselective epoxidation under Sharpless conditions followed by DDQ deprotection led to the formation of laulimalide analogue 29. We were pleased to observe that our analogue displays significant activity against Granta 519 and Jurkat cell lines with an IC50 of 200 nM and 182 nM respectively.

In conclusion, the use of atom economical transformations such as a rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization to form the endocyclic dihydropyran, a dinuclear zinc-catalyzed asymmetric glycolate aldol to prepare the syn 1,2-diol and an intramolecular ruthenium-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling via isomerization to build the macrocycle enabled us to synthesize laulimalide (1) by an efficient and convergent pathway. Interestingly, the designed synthetic route allowed us to prepare an analogue of the natural product (29) that possesses significant cytotoxic activity. More importantly, this work further highlights the power of the ruthenium-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling in the context of macrocyclizations via carbon-carbon bond formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge P. Crews (UC Santa Cruz) for providing an authentic sample of laulimalide. We also thank J. Flygare, J.-P. Stephan and P. Chan at Genentech for biological testings of our laulimalide analogue. W. M. S. thanks the National Institutes of Health for a post-doctoral fellowship. We thank the General Medical Sciences Institute of NIH (GM 33049) for their generous support of our programs. We thank Johnson-Matthey for generous gifts of palladium and ruthenium salts.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental procedures, full characterization of all products, and NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Quinoa E, Kakou Y, Crews P. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3642. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corley DG, Herb R, Moore RE, Scheuer PJ, Paul VJ. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3644. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tanaka J-i, Higa T, Bernardinelli G, Jefford CW. Chem Lett. 1996:255. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jefford CW, Bernardinelli G, Tanaka J-i, Higa T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:159. [Google Scholar]; (e) Johnson TA, Tenney K, Cichewicz RH, Morinaka BI, White KN, Amagata T, Subramanian B, Media J, Mooberry SL, Valeriote FA, Crews P. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3795. doi: 10.1021/jm070410z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooberry SL, Tien G, Hernandez AH, Plubrukarn A, Davidson BS. Cancer Res. 1999;59:653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Ghosh AK, Wang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11027. doi: 10.1021/ja0027416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh AK, Wang Y, Kim JT. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8973. doi: 10.1021/jo010854h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mulzer J, Öhler E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:3842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Paterson I, De Savi C, Tudge M. Org Lett. 2001;3:3149. doi: 10.1021/ol010150u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Enev VS, Kaehlig H, Mulzer J. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10764. doi: 10.1021/ja016752q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wender PA, Hedge SG, Hubbard RD, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4956. doi: 10.1021/ja0258428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Crimmins MT, Stanton MG, Allen SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:5958. doi: 10.1021/ja026269v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Williams DR, Liang M, Mullins RJ, Stites RE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4841. [Google Scholar]; (i) Nelson SG, Cheung WS, Kassick AJ, Hilfiker MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13654. doi: 10.1021/ja028019k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Ahmed A, Hoegenauer EK, Enev VS, Hanbauer M, Kaehlig H, Öhler E, Mulzer J. J Org Chem. 2003;68:3026. doi: 10.1021/jo026743f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Gallagher BM, Jr, Fang FG, Johannes CW, Pesant M, Tremblay MR, Zhao H, Akasaka K, Li XY, Liu J, Littlefield BA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:575. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Uenishi J, Ohmi M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:2756. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Gollner A, Altmann KH, Gertsch J, Mulzer J. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:5979. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trost BM. Science. 1991;254:1471. doi: 10.1126/science.1962206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne GB. J Org Chem. 1962;27:3819. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a review, see: Trost BM, Toste FD, Pinkerton AB. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2067. doi: 10.1021/cr000666b.

- 7.Still WC, Gennari C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:4405. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Julia M, Paris JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973:4833. [Google Scholar]; (b) Blakemore PR, Cole WJ, Kocieński PJ, Morley A. Synlett. 1998:26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Lee C. Org Lett. 2002;4:4369. doi: 10.1021/ol027104u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trost BM, Ito H, Silcoff E. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3367. doi: 10.1021/ja003871h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a report on the unique reactivity of N-acylpyrroles, see: Evans DA, Borg G, Scheidt KA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:3188. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3188::AID-ANIE3188>3.0.CO;2-H.

- 12.For the use of N-(2-hydroxyacetyl)pyrrole as a donor in a Mannich-type reaction, see: Harada S, Handa S, Matsunaga S, Shibasaki M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4365. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501180.

- 13.The PMP-acetal opening afforded a 3:1 mixture of separable regioisomers according the 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. The minor undesired regioisomer could be recycled upon exposure to DDQ to give back the starting acetal, thus increasing the overall efficiency.

- 14.Frick JA, Klassen JB, Bathe A, Abramson JM, Rapoport H. Synthesis. 1992:621. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takano S, Shimazaki Y, Moriya M, Ogasawara K. Chem Lett. 1990:1177. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trost BM, Rhee YH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7482. doi: 10.1021/ja0344258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For the use of the Ru-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling to form macrocycles, see: Trost BM, Harrington PE. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5028. doi: 10.1021/ja049292k.Trost BM, Harrington PE, Chisholm JD, Wroblesky ST. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13598. doi: 10.1021/ja053365y.Nakamura S, Kikuchi F, Hashimoto S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:7091. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802729.

- 18.Zoretic PA, Chambers RJ, Marbury GD, Riebiro AA. J Org Chem. 1985;50:2981. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grieco PA, Gilman S, Nishizawa M. J Org Chem. 1976;41:1485. [Google Scholar]

- 20.For a review on 1,3-isomerizations of allylic alcohols, see: Bellemin-Laponnaz S, Le Ny JP. C R Chim. 2002;5:217.

- 21.Bellemin-Laponnaz S, Gisie H, Le Ny J-P, Osborn JA. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:976. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RA, Sharpless KB. In: Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. Ojima I, editor. VCH Publishers; New York: 1993. p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- 23.While space limitations preclude a detailed discussion of the stereochemical assignments for newly formed stereogenic centers, the correctness of the assignments is verified by the comparison of the natural product whose stereochemistry is well-established.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.