Abstract

The nonclassical MHC class-I molecule, FcRn, salvages both IgG and albumin from degradation. Here we introduce a mechanism-based kinetic model for human to quantify FcRn-mediated recycling of both ligands based on saturable kinetics and data from the literature using easily measurable plasma concentrations rather than unmeasurable endosomal concentrations. The FcRn-mediated fractional recycling rates of IgG and albumin were 142% and 44% of their fractional catabolic rates, respectively. Clearly, FcRn-mediated recycling is a major contributor to the high endogenous concentrations of these two important plasma proteins. While familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia is caused by complete FcRn deficiency, the hypercatabolic IgG deficiency of myotonic dystrophy could be explained, based on the kinetic analyses, by a normal number of FcRn with lowered affinity for IgG but normal affinity for albumin. A simulation study demonstrates that the plasma concentrations of IgG and albumin could be dynamically controlled by both FcRn-related and -unrelated parameters.

Keywords: FcRn, IgG, albumin, saturable kinetics, recycling, fractional catabolic rate, steady-state, myotonic dystrophy, familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia, intravenous immunoglobulin

INTRODUCTION

IgG and albumin, despite their disparate forms and functions, have long been known to share two unique characteristics; namely, their lengthy lifespans and an inverse relationship between their serum concentrations and half-lives [1,2]. These unique characteristics had been explained by a saturable receptor-mediated mechanism that protects both IgG [3] and albumin [4] from intracellular degradation after nonspecific pinocytic uptake, allowing them to be recycled to the cell surface and into the extracellular milieu for continuing circulation. In the last decade the responsible receptor was identified as FcRn, a nonclassical MHC class-I molecule, that bears distinct and independent binding sites for both ligands [5-10]. FcRn is also largely responsible for the peripartum transport of IgG from mother to offspring [11]. It is further known that animals deficient in FcRn catabolize IgG and albumin more rapidly than the normal animal and manifest low plasma concentrations of both molecules [5-10,12,13].

To characterize the in vivo biological and physiological action of FcRn, several approaches focused exclusively on IgG as the ligand even before FcRn was discovered: The maximum recycling rate (Jmax) and the fractional intrinsic plasma catabolic rate (kint) of IgG were calculated using a receptor-based kinetic model [2], but the IgG concentration at which the half-maximal recycling rate is reached (Km), a key parameter characterizing FcRn saturation, was not determined. As well, the biological implications of these receptor-mediated processes were not fully evaluated. Although mathematical equations have precisely described the relationship between serum IgG concentration and the fractional plasma catabolic rate (kcat) in both humans and mice based on sigmoidal curve fitting [14], these predictive equations were empirical rather than mechanistic, and the equation-based parameters lacked physiologically meaningful information such as recycling efficiency and capacity for IgG. Although a mechanism-based IgG pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model has been developed [12], the premise of “kinetic indistinguishability” between plasma and site of catabolism [15] was not considered. Furthermore, there has been no quantitative in vivo characterization of the turnover of albumin, the other FcRn ligand [8], despite its importance in fluid physiology [13].

Two distinct diseases may be manifestations in part of FcRn malfunction. First, familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia (FHH) [2,16], showing hypercatabolism and low plasma concentrations of both IgG and albumin, results from a deficiency of FcRn due to a mutant β2-microglobulin (B2m) gene [10,17]. Second, patients with myotonic dystrophy (DM) show hypercatabolism and plasma deficiency of only IgG but not albumin. One could explain DM by postulating a mechanism that partially disrupts FcRn-IgG binding, leaving the albumin interaction intact [16,18,19]. While these diseases have been extensively investigated, the precise mechanisms of IgG and albumin turnover in these situations have not been fully described.

Although the FcRn-mediated recycling of two ligands is mechanistically and quantitatively well-characterized in the mouse [5], it has not been clearly described in human. Therefore, we pursue four objectives in the present study: First, we introduce a mechanism-based FcRn-mediated kinetic turnover model to characterize homeostasis of IgG and albumin. Second, we quantify FcRn-mediated recycling of IgG and albumin in human based on receptor-saturable kinetics using data from the literature. Third, based on our quantitative understanding of FcRn recycling kinetics we offer a hypothesis to explain the hypercatabolic IgG deficiency of DM. Lastly, we simulate steady-state plasma concentrations of IgG and albumin under different physiological conditions to derive implications and potential applications of our model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The integrated kinetic model

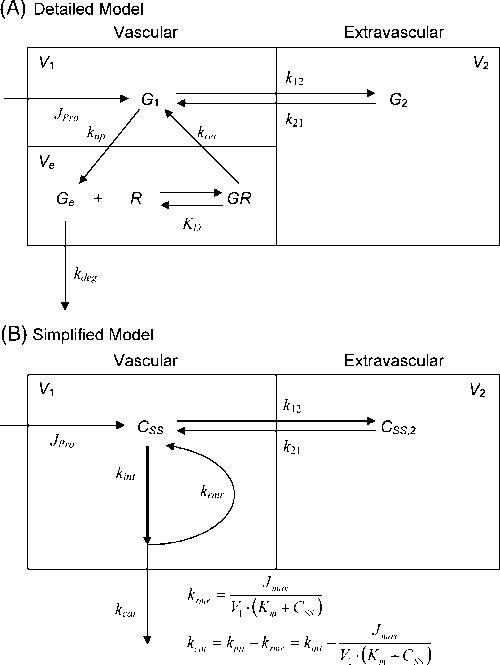

According to early turnover studies the degradation of IgG and albumin occurs in the vascular space, most likely in the endothelium and sites kinetically indistinguishable from the plasma such as parenchymal cells of organs with discontinuous and fenestrated endothelia [2,15,20-23]; Therefore, we lumped these sites into a single compartment which we refer to as the “vascular” compartment. Although the catabolic site of both proteins in the absence of FcRn has not been identified with certainty, we have assumed that both proteins are catabolized in the vascular compartment [2]. Fig. 1 shows a kinetic model with details in the legend for IgG turnover in human and mouse that integrates a variety of physiological facts. The model features the conventional two compartments, vascular and extravascular [2,14], mandated by the usually [5-8] but not invariably [12] biphasic plasma IgG decay curves seen, regardless of FcRn presence, after intravenous administration of IgG. The full model (Fig. 1A) features a functional catabolic and recycling site within the vascular compartment consisting of endosome-rich endothelium [24] into which plasma IgG is constitutively pinocytosed by a fluid-phase endocytic process at a fractional uptake rate (kup), which is FcRn-independent since FcRn binding takes place after acidic sorting endosomes are formed [25], unlike cell-surface receptor-mediated uptake of LDL or transferrin. While pinocytosis/exocytosis is potentially bidirectional, kup is a fractional rate of “net” movement (thus smaller in magnitude than the ‘real’ unidirectional uptake rate) from the plasma into the sorting endosomes where IgG binds FcRn according to its binding affinity (equilibrium binding constant; KD) in an acidic endosomal environment [25]. Considering known aspects of receptor-ligand interaction and the law of mass action, equilibrium is established within the endosome between free and FcRn-bound IgG. We presume that IgG in the sorting endosome is provided by both plasma and extravascular compartments by bidirectional pinocytosis (not shown). IgG concentrations in the plasma and extravascular compartments are typically at steady-state. Therefore, the plasma concentration is not identical to but is an index for endosomal unbound IgG concentration (see Results and Discussion). FcRn-bound IgG is recycled to the plasma at a rate controlled by a fractional endosomal recycling rate (krec) whereas unbound IgG is degraded [25-27] at a rate controlled by a fractional endosomal degradation rate (kdeg). The distribution of IgG between the vascular and extravascular compartments was assumed to be FcRn-independent and is controlled by fractional intercompartmental distribution rates (k12 and k21).

Figure 1. A proposed model for the recycling of IgG in human.

Plasma and endothelium, the site of protein degradation, are lumped together into the vascular compartment based on early studies showing that protein degradation occurs in a compartment kinetically indistinguishable from plasma [2,15,20-23]. Although the catabolic site of both proteins in the absence of FcRn has not been identified with certainty, we have assumed that both proteins are catabolized in the vascular compartment [2]. Refer to Materials and Methods for details. Panel A: A detailed descriptive model. Panel B: A simplified model that was used to determine Km and associated kinetic parameters. Kinetic parameters in Fig. 1B were mathematically expressed using the parameters in Fig. 1A: kint = kup; Km = KD×G1/Ge; Jmax = krec×Rtotal×Ve. Abbreviations used: G2 or CSS,2, extravascular IgG concentration; V1, vascular volume (~plasma volume); V2, extravascular volume; Ve, endosomal volume.

Theoretical considerations of recycling of a saturable FcRn

To link the kinetic considerations above to the readily accessible plasma IgG concentration, we proposed a simplified kinetic model (Fig. 1B). Here, we considered two kinds of turnover rates: absolute and fractional rates. The absolute rates (designated with J; μmol/d/kg) are products of the corresponding fractional rate (k; d-1) and amount (= concentration × volume of distribution; μmol/kg). At steady-state, the rate of production (Jpro) equals the rate of catabolism (Jcat; μmol/d/kg), which is defined as:

| Eq.1 |

where kcat (d-1) represents the fractional catabolic rate of IgG from the vascular compartment, V1 (mL/kg) is the apparent volume of the vascular compartment of IgG, almost identical to the plasma volume, and CSS (μM) is the steady-state plasma concentration of IgG. Here, kcat reflects the ‘apparent’ or ‘measured’ fractional catabolic rate, being the fractional ‘intrinsic’ catabolic rate (kint; d-1) minus a fractional FcRn-mediated recycling rate (krmr; d-1) that accounts for recycling of endocytosed IgG back to the cell surface (kcat = kint − krmr). Therefore, both krmr and kcat in the presence of FcRn change in relation to plasma IgG concentration because FcRn-mediated recycling is a saturable process. The ‘absolute’ (as opposed to ‘fractional’) rate of receptor-mediated IgG recycling (Jrmr; μmol/d/kg) is expressed by saturable Michaelis-Menten type kinetics and exists only in the presence of FcRn (see Appendix for detail):

| Eq.2 |

where Jmax (μmol/d/kg) is the maximal recycling rate of IgG by an FcRn-mediated process, and the Michaelis constant Km (μM) is the plasma IgG concentration at which a half maximal IgG recycling rate is achieved. Since there is no recycling process in the absence of FcRn, kcat in this case would be identical to kint with krmr being zero. The kint is a first-order rate constant that is independent of substrate concentration and FcRn expression because it is a substrate-independent ‘net’ pinocytic rate constant (thus identical to kup; Fig. 1A). FcRn-independent parameters were calculated or adapted from the literature; k12, k21, and V1 for IgG were 0.156 d-1, 0.158 d-1, and 42.0 mL/kg, respectively [16]. Therefore, from Equation 2,

| Eq.3 |

This equation is equivalent to that proposed by Brambell [3] and Waldmann and Strober [2]. The kinetic parameters in the simplified model (Fig. 1B) can be mathematically expressed in terms of the parameters of the detailed kinetic model (Fig. 1A; see legends).

Determination of in vivo Km and associated kinetic parameters of FcRn-mediated IgG recycling in human

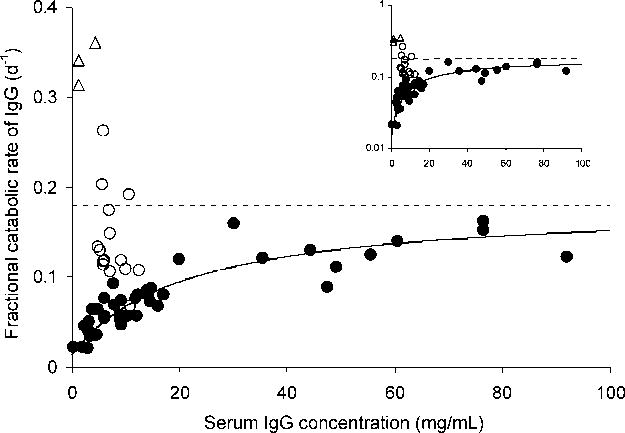

Equation 3 indicates that kcat would be identical to kint when IgG CSS is sufficiently high. Both Jmax and kint values are available in the literature [2]; Jmax = 0.98 μmol/d/kg and kint = 0.18 d-1. Therefore, Km for IgG was determined by nonlinear least-squares regression analysis based on Equation 3, fitting the kcat vs. CSS profile (Fig. 2) using WinNonlin 4.0 (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA).

Figure 2. The relationship between kcat and the serum IgG concentration obtained from patients with a wide range of IgG concentrations.

The filled circles represent the experimentally determined values, redrawn from Waldmann and Strober [2], and the solid line represents the least-squares fit of Equation 3 for Km, with other parameter values from Waldmann and Strober [2]. The dotted line indicates the asymptote value of kcat when the serum IgG concentration approaches infinity, which is equivalent to the IgG fractional intrinsic degradation rate, kint. The open circles and triangles represent kcat values from DM patients [18] and FHH patients [16] (three independent observations from the two siblings), respectively. The inset shows the same graph on a semi-logarithmic scale.

The degree of FcRn saturation by plasma IgG concentration is defined by a quotient, Jrmr/Jmax, which is equivalent to CSS/(Km+CSS) from Equation 2. FcRn is fully saturated (degree = 1) at infinite IgG concentration and half-saturated (0.5) at Km. The recycling efficiency is defined by a quotient, Jmax/Km; thus the efficiency can be enhanced by an increase in Jmax and/or a reduction in Km. The Jpro appears to be independent to both FcRn and change in CSS [28].

In vivo kinetic characterization of FcRn-mediated albumin recycling

While early work indicated qualitatively a nonlinear concentration-catabolism relationship of albumin over a narrow range of plasma concentrations (35~55 mg/mL) [29], it was never practical to characterize quantitatively the relationship. Altering the concentration of albumin, the major colloid in plasma, likely would have provoked secondary physiological alterations that would have confounded albumin homeostasis.

Since albumin is also a substrate for FcRn, Equation 2 for IgG holds for the calculation of receptor kinetic parameters for albumin. Unlike the situation for IgG, the albumin concentration-catabolism relationship with a wide range of albumin CSS is not available from the literature, so there can be no direct analysis of albumin recycling in human. However, we can characterize the receptor-mediated kinetics for albumin from equations established for IgG since FcRn recycles both proteins by saturable processes that are independent of one another. Using Equation 3, three pieces of information for the albumin interaction with FcRn can be determined, i.e., Jmax, Km, and kint. First, the binding molar stoichiometric ratio between albumin and FcRn was unity [30], indicating that Jmax for albumin would be twice that for IgG; viz., 1.96 μmol/d/kg. We assume that FcRn recycles albumin and IgG simultaneously, as all evidence indicates that FcRn is bound to each ligand independently of the other [8]. Second, albumin kcat was reported to be 0.109 d-1 at 570 μM, the albumin CSS in normal humans. The k12 and k21 for albumin were recalculated to be 0.497 d-1 and 0.402 d-1, respectively, based on the two-compartment model from the original albumin decay data [31], and V1 was 45.5 mL/kg [16]. Third, the kcat values for albumin in analbuminemic patients were relatively well studied [32-34]. As these patients showed normal IgG concentration and catabolism, FcRn expression in these patients appears to be normal. These three relationships permit estimation of kint, Jmax and Km values for albumin using Equation 3.

Determination of in vivo Km and associated kinetic parameters of FcRn-mediated IgG recycling in DM patients

Equation 3 was also applied for the calculation of altered Km, Jmax, and associated kinetic parameters in DM patients (See Results and Discussion). Since DM patients showed a partial reduction of IgG CSS,DM (50 μM) and a moderate decrease in t1/2 (11.4 d) with kcat, DM = 0.14 d-1 with normal albumin metabolism [18], FcRn expression per se appears to be normal (Jmax,DM = Jmax; preserving 2:1 stoichiometry). Instead, the affinity of binding between FcRn and IgG appears to be decreased while normal albumin binding is preserved. Therefore, the altered Km value of FcRn for IgG in DM patients was calculated by Equation 3.

Simulation of plasma concentrations in various conditions

A series of simulations for plasma concentrations of IgG and albumin was performed using WinNonlin 4.0 by changing the already determined parameters, Jmax and Km (FcRn-related), and Jpro and kint (FcRn-unrelated) under FcRn-independent volumes of distribution (V1 and V2) and fractional intercompartmental distribution rates (k12 and k21). Since these four parameters are components of the turnover of both proteins, any changes in the parameters would result in different plasma concentration profiles of IgG and albumin. It was assumed that the effects of altered parameters were instantaneous and irreversible in order to show the difference between normal and changed status. The plasma concentration, a function of Km, Jmax, Jpro, and kint values, was simulated over the time course while all the four parameters were subjected to 0.125-, 0.25-, 0.5-, 1- (normal), 2-, 4-, and 8-fold normal values; detailed model-based differential equations used in the kinetic simulation are available in the Appendix.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

FcRn-mediated recycling kinetics for human IgG

Fig. 2, using a saturable kinetic model and redrawn from Waldmann and Strober [2], shows the serum concentration-catabolism relationship of IgG published for human subjects. The asymptotic line represents the fractional catabolic rate in the absence of FcRn (FcRn fully saturated), which is also considered to be the fractional intrinsic catabolic rate of IgG (kint; 0.18 d-1). Using published values for the maximal FcRn-mediated recycling rate (Jmax), the fractional catabolic rate from plasma (kcat), and the plasma volume (V1) [2,16], we determined the Michaelis constant (Km) based on our integrative two-compartment kinetic model (Fig. 1) using nonlinear least-squares regression. Table 1 lists the associated kinetic parameters for FcRn. The Km of FcRn for IgG was 140 ± 2.25 μM (estimate ± standard error; 21.0 ± 0.337 mg/mL); the degree of FcRn saturation at physiological (normal) IgG plasma concentration (80.7 μM or 12.1 mg/mL) was calculated to be 0.365, indicating that in normal human approximately two-thirds of FcRn remain available for IgG recycling.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the recycling of IgG and albumin by FcRn in normal humans and DM patients. A reduced binding affinity between FcRn and IgG explains the lower CSS and greater kcat of IgG without alteration of albumin metabolism.

| Parameters | Units | Normal | DM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | Albumin | IgG | ||

| Maximal rate of FcRn-mediated recycling (Jmax); i.e., in vivo recycling capacity | μmol/d/kg | 0.98* | 1.96 | 0.98* |

| mg/d/kg | 147* | 131 | 147* | |

| Plasma concentration at which a half Jmax reached (Km); The Michaelis constant | μM | 140 | 319 | 533 |

| mg/mL | 21.0 | 21.4 | 80.0 | |

| Receptor recycling efficiency (Jmax/Km) | mL/d/kg | 7.00 | 6.12 | 1.84 |

| Fractional intrinsic catabolic rate (kint) | d-1 | 0.180* | 0.157 | 0.180* |

| Fractional catabolic rate (kcat) at CSS | d-1 | 0.0743 | 0.109* | 0.140* |

| Fractional recycling rate (krmr) at CSS | d-1 | 0.106 | 0.048 | 0.040 |

| Vascular compartment volume (V1) | mL/kg | 42.0* | 45.5* | 42.0* |

| Steady-state plasma concentration (CSS) | μM | 80.7* | 570* | 50.0* |

| mg/mL | 12.1* | 38.2* | 7.5* | |

| Degree of FcRn saturation at CSS | unitless | 0.365 | 0.641 | 0.0857 |

| FcRn-mediated recycling rate (Jrmr at CSS) | μmol/d/kg | 0.358 | 1.25 | 0.168 |

| mg/d/kg | 53.7 | 84.0 | 25.2 | |

| Production rate (Jpro) at CSS | μmol/d/kg | 0.252 | 2.83 | 0.294 |

| mg/d/kg | 37.8 | 189 | 44.1 | |

| Ratio of recycling rate to production rate (Jrmr/JPro) | unitless | 1.42 | 0.444 | 0.571 |

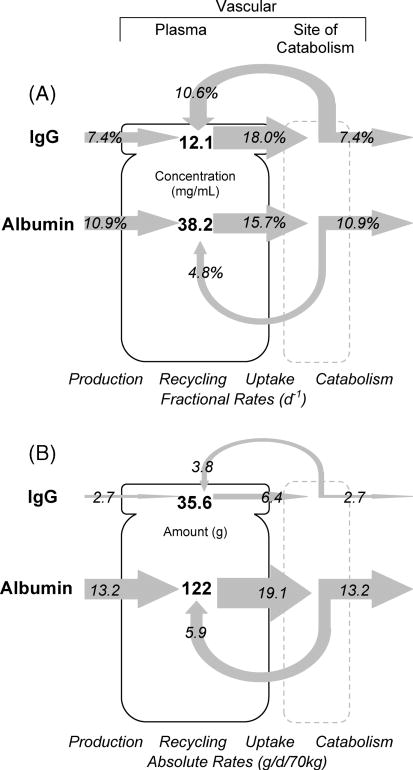

Using Equation 3 and the determined Km, we calculated the IgG kcat value in normal human to be 0.0743 d-1, which differed only ~10% from 0.067 d-1, the measured normal value [16]. The ratio of kcat to kint (0.41) in normal human indicates that IgG kcat would be reduced by 59% from the maximally possible physiological kcat that would occur in either the absence of FcRn (i.e., kint) or at infinite IgG concentration where all functional FcRn molecules would be saturated. The catabolic rate of IgG is thereby reduced by the presence of the FcRn-mediated recycling process. Since a constant steady-state plasma concentration (CSS) of plasma proteins is maintained by a balance between their production and catabolism, a reduction in kcat leads to an increase in CSS. Using Equation 2 the calculated fractional and absolute rates of receptor- mediated recycling were 0.106 (krmr = kint − kcat) and 0.358 μmol/d/kg (53.7 mg/d/kg), respectively. Since the rates of production (Jpro) and catabolism (Jcat) are equal under steady-state conditions (Equation 1), the effect of FcRn-mediated recycling can be evaluated by comparing the rates between recycling and production (Fig. 3). The Jpro of IgG in the normal human was estimated to be 0.252 μmol/d/kg (37.8 mg/d/kg) using Equation 1; a similar value (33 mg/d/kg) was reported by Waldmann and Strober [2]. Therefore, the FcRn-mediated IgG recycling rate was 42 % greater than the IgG production rate, indicating that the recycling of IgG, not its production, is the dominant process for maintaining the IgG plasma concentration in human. The plasma concentration of IgG, thus, is controlled not only by antigen-driven production of IgG but by FcRn-mediated salvage of IgG from degradation.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of IgG and albumin turnover in humans at their normal plasma concentrations.

Plasma concentrations and whole-body turnover rates (as fractional rates in Panel A and as absolute rates in Panel B) for IgG and albumin, both FcRn substrates, are quantitatively represented to scale for a 70 kg human. Panel A: Shown are the plasma concentrations (CSS; 12.1 and 38.2 mg/mL for IgG and albumin), the fractional catabolic rates (kcat; 7.4 and 10.9%/d), the FcRn-mediated fractional recycling rates (krmr) back to the plasma (10.6 and 4.8%/d), and the ‘fractional’ production rates (7.4 and 10.9%/d), which equal the fractional catabolic rate at steady-state. The krmr was calculated using Equation 2 based on Michaelis-Menten type saturable kinetics. The figure is to scale: areas are proportional to plasma concentrations and arrow widths to rates. Panel B: Units are in grams for a normal human with 70 kg body weight. Shown are the absolute catabolic rates (Jcat; 2.65 and 13.2 g/d), the FcRn-mediated recycling rates (Jrmr) back to the plasma (3.76 and 5.88 g/d), and the production rates (Jpro; 2.65 and 13.2 g/d) along with the intravascular pool sizes (35.6 and 122 g), the product of steady-state plasma concentration and the volume of distribution of the protein (CSS × V1). The Jcat is the product of the fractional catabolic rate (kcat) and the pool size in the normal human (CSS × V1). The Jrmr was calculated using Equation 2 based on Michaelis-Menten type saturable kinetics, identical to the product of krmr × CSS × V1. Note that while a higher fraction (2/3 rather than 1/3) of moles of IgG (krmr/kint = 10.6/18.0 ≈ 2/3) than albumin (4.8/15.7 ≈ 1/3) are recycled from degradation (Panel A), the ‘molar’ recycling ratio of IgG to albumin (Jrmr,IgG/Jrmr,albumin) at physiological concentrations is lower, about 1 to 3.5 (see Results and Discussion). The figure is to scale: areas for plasma amount and arrow widths for rates.

FcRn-mediated kinetics for human albumin

Since albumin is recycled by FcRn as is IgG, albeit in an IgG-independent manner, we applied to albumin our results from the kinetic analysis of the FcRn-IgG interaction. The kinetic parameter values of FcRn for albumin are also listed in Table 1. The model-based, calculated kint for albumin was 0.157 d-1, indicating that albumin has slightly lower susceptibility to intrinsic degradation than does IgG (0.18 d-1). However, because human studies are characterized by large variation and because the albumin parameters are derived from the IgG data, the kint values of both proteins may actually be quite close. The albumin Jmax was taken to be twice that for IgG based on the binding stoichiometries of FcRn for the two substrates [30]. The albumin Km was calculated to be 319 μM (21.4 mg/mL), more than twice that for IgG (140 μM), suggesting a reduction in the recycling efficiency of FcRn for albumin as compared with that for IgG. However, the comparatively higher Km in FcRn-mediated albumin recycling appears to be partially overcome by its higher recycling capacity (elevated Jmax). Using the ratio Jmax/Km to quantify the recycling efficiency, the ratio for albumin was 87% of that for IgG (Table 1). In contrast to IgG, the degree of FcRn saturation for albumin recycling at physiological albumin concentrations (570 μM or 38.2 mg/mL) was 0.641, suggesting that almost one-third of the FcRn molecules are available for albumin recycling. Illustrating these relationships, Fig. 3 presents a diagram that quantitatively depicts IgG and albumin FcRn-mediated kinetics with both ‘fractional’ rates (k’s; Fig. 3A; d-1) and ‘absolute’ rates (J’s; Fig. 3B; g/d/70 kg converted from μmol/d/kg). The figure is scaled such that the areas of the plasma compartment represent concentrations or amounts and the arrow widths represent fractional or absolute rates. While a larger fraction of IgG (0.11 d-1) than albumin (0.05 d-1) is salvaged from the degradation pathway (krmr), the ratio of absolute ‘molar’ recycling rates (Jrmr) of albumin to IgG is higher, about 3.5 to 1 (1.25 vs. 0.358 μmol/d/kg; Table 1).

In human, Jpro and Jrmr of albumin were 2.83 and 1.25 μmol/d/kg, respectively, indicating that about two-thirds of the plasma albumin concentration is maintained by production rather than by recycling (Table 1). In contrast, the mouse Jpro was the same as Jrmr [10,13]. The more efficient albumin recycling in the mouse may suggest a larger Jmax (e.g., increase in FcRn density per kg body weight) and/or a smaller Km compared with human. Nonetheless, in human the albumin recycling rate is considerable compared with its production rate, indicating the significant role of FcRn in albumin homeostasis in normal humans.

Pathophysiology of an FcRn-related disease: FHH

We have recently characterized the molecular defect in two siblings with FHH who presented with a phenotype indistinguishable from the FcRn-deficient knockout mouse [16]; namely, IgG and albumin deficiency resulting from hypercatabolism. These siblings are B2m-deficient as a result of a missense mutation in the B2m gene [17] and presumably express little or no functional FcRn. Analyzing these siblings further, we show in Fig. 2 that the average kcat for IgG of the two siblings was greater than IgG kcat in normal humans (0.343 vs. 0.067 d-1); the albumin kcat in these siblings was also greater than the albumin kcat in normal subjects (0.219 vs. 0.109 d-1). These kcat values for both proteins in these siblings are even greater than kint values (0.180 d-1 for IgG and 0.157 d-1 for albumin), the maximally achievable fractional catabolic rates in the absence of FcRn, suggesting that these siblings may have manifested, in addition to severe FcRn deficiency, an additional hypercatabolic effect, perhaps more general than that caused by FcRn-deficiency alone. Diabetes mellitus is one possible cause of protein hypercatabolism [35,36] that both patients manifested, one requiring insulin and the other showing a positive diabetic glucose tolerance test. We note as well the single determination of IgA decay showing a shortened t1/2 [16]. However, the fact that the serum concentrations of IgG and albumin were significantly lower than the normal values while those of other plasma proteins (transferrin, IgA, IgM, and IgD) were normal [16] suggests that the loss of IgG and albumin in the absence of FcRn was so severe that the body could not maintain the normal CSS. This affirms a critical role for FcRn in the homeostasis of IgG and albumin.

Pathophysiology of DM, a second putatively FcRn-related disease

DM is a genetic disease manifesting what appears to be a generalized defect in pre-mRNA processing [37-39]. Its phenotype is different from FHH. Most DM patients have a low CSS (50 μM) and a short t1/2 (11.4 d) for IgG (both deviated from normal less markedly than in FHH) with a normal predicted IgG production rate and with normal albumin CSS and t1/2 [18]. Individual values of kcat in DM patients are shown in Fig. 2. No satisfactory potential mechanism for IgG hypercatabolism in DM patients was available until FcRn was discovered. It was recently suggested that FcRn expression is reduced by 42% [19], but this hypothesis predates the discovery that albumin binds to FcRn independently of IgG and protects albumin also from degradation [8]. It is also helpful to know that DM patients have normal steady state concentrations of FcRn α-chain mRNA [40].

Based upon these observations and our calculations, we propose that the defect in DM results in a lowered but not absent affinity of FcRn for IgG while the binding of FcRn to albumin is unhampered and the number of FcRn expressed is normal (See Materials and Methods). The magnitude of the IgG kcat [18] is greater than normal but smaller than the asymptote as shown in Fig. 2. Since albumin metabolism is normal in DM patients, a change in FcRn expression, alone, does not explain the DM phenotype. Therefore, we hypothesize the following: In DM patients the amount of FcRn expressed (capacity; Jmax) and the stoichiometry of FcRn for both albumin and IgG are normal, as is FcRn affinity for albumin. The defect is a low affinity of FcRn for IgG. The IgG Km,DM is 533 μM, substantially increased (4-fold) compared with the normal Km; associated kinetic parameters are listed in Table 1. Our analysis indicates that the “efficiency” of receptor recycling (Jmax/Km) for IgG was greatly reduced in DM to 1.84 from the normal value (7.00), indicating that FcRn-mediated recycling of IgG was about 25% as efficient as normal. The reduced ratio of Jrmr/Jpro in DM (0.571 vs. 1.42) suggests that the IgG CSS is mostly maintained by IgG production rather than recycling, which is different from the normal condition.

We suggest two possible explanations for a low FcRn affinity for IgG based on the current notion that patients with DM manifest a generalized defect in pre-mRNA processing [37-39]. Perhaps the FcRn α-chain itself is abnormally spliced in a subtle but critical fashion such that the IgG binding site is distorted while the albumin binding site is preserved. Perhaps a second unknown cellular molecule, altered in DM, distorts the interaction of FcRn with IgG but not with albumin. Pursuit of the exact mechanism is beyond our current scope.

Comparing in vitro KD and in vivo Km

Our calculated in vivo Km values for both ligands are much higher (> 50-fold) than in vitro KD, < 1 μM for human IgG [41] and 5 μM for human albumin [30]. The values differ because they are referenced to ligand concentrations in different places. The KD value is based upon the concentration of “unbound” ligand in direct equilibrium with the ligand “bound” to FcRn in vitro and in acidic endosomes. The Km value reflects ligand plasma concentration upon entering the endosome. The two concentrations (plasma and acidic endosome) are assumed to be directly related (indexed), with the acidic endosomal concentration being lower due to binding of some endosomal ligand to FcRn and presumably to other endosomal processes. The plasma-based Km value, while indirectly representing the KD value, has the practical advantage that it can be estimated from ligand plasma concentration and can be manipulated to predict and/or modulate ligand concentrations in vivo. Therefore, Km is an important parameter in quantifying the degree of FcRn saturation and receptor-mediated recycling efficiency based on the plasma IgG concentration. Further, Km can provide a guideline for clinical intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy where the clearance of pathogenic autoantibody appears dependent upon the saturation of FcRn [42].

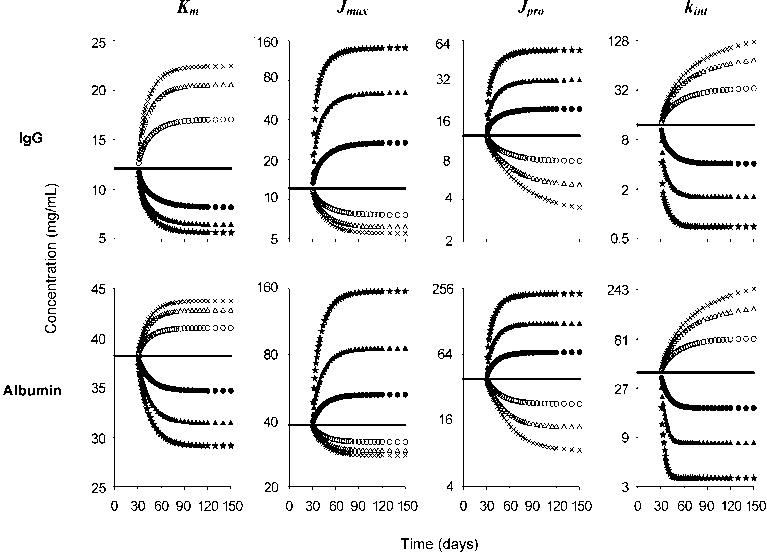

Sensitivity of CSS to perturbation of model parameters and clinical implications of model-based simulation

To understand how changes in the parameters of the model would affect plasma concentrations, we simulated IgG and albumin plasma concentrations after step changes in model parameter values (Fig. 4). Through a series of simulations using our model of FcRn ligand turnover, we demonstrated how the CSS of both IgG and albumin is altered by changing values of the four main kinetic/dynamic parameters, Km, Jmax, Jpro, and kint. Increases in Jmax and Jpro resulted in elevations of CSS, while increases in Km and kint lowered CSS. It is notable that CSS was linearly changed by alteration of FcRn-unrelated parameters (Jpro and kint) but nonlinearly changed by FcRn-related parameters (Km and Jmax). Furthermore, the time to reach a new CSS was unchanged after perturbation of Km and Jmax whereas an increase in Jpro and kint (FcRn-unrelated) reached a new CSS more rapidly than after a decrease in the parameters. These responses indicate dynamic and specific control of CSS by changes in Km and Jmax of IgG and albumin. Altered model parameter values appear to reflect certain human pathologic situations as follows.

Figure 4. Sensitivity of model responses (Fig. 1) to variation of model parameter values.

Plasma concentrations of IgG (top panels) and albumin (bottom panels) were simulated for step changes in values of Km, Jmax, Jpro, and kint. Compartmental volumes and fractional distribution rates were assumed to be constant. Kinetic changes of plasma concentrations were simulated by model-based differential equations (see Appendix) over time while each parameter was varied above and below normal (solid line); the following variations were used: 0.125-fold (×), 0.25-fold (open triangle), and 0.5-fold (open circle), 2-fold (filled circle), 4-fold (filled triangle), and 8-fold (filled star). Note that linear changes in the four parameters induced linear (Jpro and kint) and nonlinear (Km and Jmax) changes in CSS as well as the time to reach the new CSS (see Results and Discussion). Note that Km is shown with linear scale whereas others are semilogarithmic scales.

Changes in Km and Jmax

The rationale for the use of IVIG in the therapy of autoantibody-mediated autoimmune diseases is based in part on its capacity to block FcRn [14]. Such blockade results from an increase in IgG CSS, which in turn causes an increase in kcat of IgG antoantibody (increasing the denominator of Equation 3). This same result might be achieved alternatively by an increase in IgG Km, the other denominator component of Equation 3. DM is one putative example of a pathological increase in Km of IgG (above). Moreover, increasing Km (e.g., by using specific FcRn inhibitors) may be clinically useful as a single treatment or in combination with IVIG to increase the efficacy of the IVIG. In contrast to changes resulting in ligand-specific alterations, changes in Jmax would likely result in alteration in CSS of both IgG and albumin. While receptor down-regulation would be predicted to diminish pathogenic IgG antibodies, a collateral albumin loss would be expected as well. FHH patients are a pathological example of Jmax = 0 since they lack FcRn.

Changes in Jpro and kint

An increase in IgG Jpro can be seen in myeloma patients whereas hypogammaglobulinemia patients have a lowered Jpro. Patients with liver disease have a lowered Jpro for albumin. These changes directly alter the CSS (Fig. 4). A change in kint is nonspecific as it refers to the fractional uptake rate destined for degradation; thus not only IgG and albumin but also other plasma proteins are affected in a similar manner. Hyperthyroidism and diabetes mellitus patients show increased metabolic activity [35], which increases kint, similar to what we suggest in the case of FHH.

Acknowledgments

WinNonlin software was generously provided through an Academic License by Pharsight Corporation. This work was supported in part by grants HD38764, CA88053, and AI57530 from the NIH.

Abbreviations

- B2m

β2-microglobulin

- CSS

the steady-state concentration in plasma or serum

- DM

myotonic dystrophy

- FcRn

Fc receptor (neonatal)

- FHH

familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobulin

- Jcat

the absolute catabolic rate from the vascular (plasma) compartment

- Jint

the absolute intrinsic catabolic rate in the absence of FcRn

- Jmax

the maximal FcRn-mediated recycling rate

- Jpro

production rate

- Jrmr

the absolute receptor-mediated recycling rate

- kcat

the fractional catabolic rate from the vascular (plasma) compartment

- kint

the fractional intrinsic plasma catabolic rate in the absence of FcRn

- Km

the Michaelis constant defined as the plasma protein concentration at which one-half maximal recycling rate of a protein is reached

- krmr

the fractional FcRn-mediated recycling rate

- t1/2

the terminal half-life or survival half-life

- V1

the plasma or vascular compartment volume

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freeman T. Haptoglobin metabolism in relation to red cell destruction. Protides of the Biological Fluids. 1964;12:344–352. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldmann TA, Strober W. Metabolism of immunoglobulins. Prog Allergy. 1969;13:1–110. doi: 10.1159/000385919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brambell FW, Hemmings WA, Morris IG. A Theoretical Model of Gamma-Globulin Catabolism. Nature. 1964;203:1352–1354. doi: 10.1038/2031352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultze HE, Heremans JF. Nature and metabolism of extracellular proteins. Vol. 1. Elsevier; New York: 1966. Molecular biology of human proteins: with special reference to plasma proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junghans RP, Anderson CL. The protection receptor for IgG catabolism is the beta2-microglobulin-containing neonatal intestinal transport receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5512–5516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES. Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:690–696. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel EJ, Wilsker DF, Hayes KC, Schoenfeld D, Simister NE. Increased clearance of IgG in mice that lack beta 2-microglobulin: possible protective role of FcRn. Immunology. 1996;89:573–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL. The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J Exp Med. 2003;197:315–322. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roopenian DC, Christianson GJ, Sproule TJ, Brown AC, Akilesh S, Jung N, Petkova S, Avanessian L, Choi EY, Shaffer DJ, Eden PA, Anderson CL. The MHC class I-like IgG receptor controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis, and fate of IgG-Fc-coupled drugs. J Immunol. 2003;170:3528–3533. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson CL, Chaudhury C, Kim J, Bronson CL, Wani MA, Mohanty S. Perspective - FcRn transports albumin: relevance to immunology and medicine. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel EJ, Patel VK, Taylor SF, Marshak-Rothstein A, Simister NE. Requirement for a beta 2-microglobulin-associated Fc receptor for acquisition of maternal IgG by fetal and neonatal mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:6246–6251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of the effects of intravenous immunoglobulin on the disposition of antiplatelet antibodies in a rat model of immune thrombocytopenia. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:1206–1215. doi: 10.1002/jps.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Bronson CL, Hayton WL, Radmacher MD, Roopenian DC, Robinson JM, Anderson CL. Albumin turnover: FcRn-mediated recycling saves as much albumin from degradation as the liver produces. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G352–G360. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00286.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleeker WK, Teeling JL, Hack CE. Accelerated autoantibody clearance by intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: studies in experimental models to determine the magnitude and time course of the effect. Blood. 2001;98:3136–3142. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane AS. The behavior of I 131-labeled plasma proteins in vivo. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1957;70:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb35374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldmann TA, Terry WD. Familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia. A disorder of endogenous catabolism of albumin and immunoglobulin. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:2093–2098. doi: 10.1172/JCI114947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wani MA, Haynes LD, Kim J, Bronson CL, Chaudhury C, Mohanty S, Waldmann TA, Robinson JM, Anderson CL. Familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia caused by deficiency of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, due to a mutant beta2-microglobulin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5084–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600548103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wochner RD, Drews G, Strober W, Waldmann TA. Accelerated breakdown of immunoglobulin G (IgG) in myotonic dystrophy: a hereditary error of immunoglobulin catabolism. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:321–329. doi: 10.1172/JCI105346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junghans RP, Ebralidze A, Tiwari B. Does (CUG)n repeat in DMPK mRNA ’paint’ chromosome 19 to suppress distant genes to create the diverse phenotype of myotonic dystrophy?: A new hypothesis of long-range cis autosomal inactivation. Neurogenetics. 2001;3:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s100480000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berson SA, Yalow RS. The distribution of I131-labeled human serum albumin introduced into ascitic fluid: analysis of the kinetics of a three compartment catenary transfer system in man and speculations on possible sites of degradation. J Clin Invest. 1954;33:377–387. doi: 10.1172/JCI102910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell RM, Cuthbertson DP, Matthews CM, McFarlane AS. Behaviour of 14C- and 131I-labelled plasma proteins in the rat. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1956;1:66–84. doi: 10.1016/0020-708x(56)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman T. The use of radioactive iodine as a trace label for plasma proteins. Protides of the Biological Fluids. 1966;14:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeve EB, Roberts JE. The kinetics of the distribution and breakdown of 1131-albumin in the rabbit. Observations on several mathematical descriptions. J Gen Physiol. 1959;43:415–444. doi: 10.1085/jgp.43.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borvak J, Richardson J, Medesan C, Antohe F, Radu C, Simionescu M, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Functional expression of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, in endothelial cells of mice. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1289–1298. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward ES, Zhou J, Ghetie V, Ober RJ. Evidence to support the cellular mechanism involved in serum IgG homeostasis in humans. Int Immunol. 2003;15:187–195. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES. Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn. J Immunol. 2004;172:2021–2029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Praetor A, Ellinger I, Hunziker W. Intracellular traffic of the MHC class I-like IgG Fc receptor, FcRn, expressed in epithelial MDCK cells. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 14):2291–2299. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junghans RP. IgG biosynthesis: no “immunoregulatory feedback”. Blood. 1997;90:3815–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen SB, Rossing N. Metabolism of albumin and γG-globulin during albumin infusions and during plasmapheresis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1967;20:183–184. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhury C, Brooks CL, Carter DC, Robinson JM, Anderson CL. Albumin Binding to FcRn: Distinct from the FcRn-IgG Interaction. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4983–4990. doi: 10.1021/bi052628y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beeken WL, Volwiler W, Goldsworthy PD, Garby LE, Reynolds WE, Stogsdill R, Stemler RS. Studies of I-131-albumin catabolism and distribution in normal young male adults. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:1312–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI104594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennhold H, Kallee E. Comparative studies on the half-life of I 131-labeled albumins and nonradioactive human serum albumin in a case of analbuminemia. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:863–872. doi: 10.1172/JCI103868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dammacco F, Miglietta A, D’Addabbo A, Fratello A, Moschetta R, Bonomo L. Analbuminemia: report of a case and review of the literature. Vox Sang. 1980;39:153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1980.tb01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldmann TA, Gordon RS, Jr, Rosse W. Studies on the metabolism of the serum proteins and lipids in a patient with analbuminemia. Am J Med. 1964;37:960–968. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bent-Hansen L, Deckert T. Metabolism of albumin and fibrinogen in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. 1988;7:159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charlton M, Nair KS. Protein Metabolism in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. J Nutr. 1998;128:323S–327S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.323S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Philips AV, Timchenko LT, Cooper TA. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savkur RS, Philips AV, Cooper TA. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mankodi A, Takahashi MP, Jiang H, Beck CL, Bowers WJ, Moxley RT, Cannon SC, Thornton CA. Expanded CUG repeats trigger aberrant splicing of ClC-1 chloride channel pre-mRNA and hyperexcitability of skeletal muscle in myotonic dystrophy. Mol Cell. 2002;10:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Wen S, Ghanaat-Pour H, Solders G, Forsberg H, Hammarstrom L. Lack of correlation between the reduction of serum immunoglobulin concentration and the CTG repeat expansion in patients with type 1 dystrophia [correction of Dystrofia] myotonica. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;144:100–104. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West AP, Jr, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure and immunoglobulin G binding properties of the human major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9698–708. doi: 10.1021/bi000749m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin F, Balthasar JP. Mechanisms of intravenous immunoglobulin action in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]