Abstract

The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen (MIBI-t) is designed to assess the three cross-situationally stable dimensions (Centrality, Regard, and Ideology) of the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998) within teenagers. Adolescent responses (N = 489) to the MIBI-t were subjected to several analyses to evaluate the psychometric character of the measure. Findings indicated that the MIBI-t represents a valid framework for African American adolescents, that its internal structure is consistent with the conceptual framework of the MMRI, and support its construct validity. Findings also indicate model invariance across grade level and gender, as well as suggest evidence of predictive validity. Further information about the MIBI-t and the full set of items are presented.

Keywords: Racial Identity, Ethnic Identity, Measurement Identity Development African American, Black, Self-Concept

An increasing body of psychological literature has focused on how African Americans define what their racial group membership means to them (Burlew, Bellow, & Lovett, 2000; Cross, 1971, 1991; Cross, Parham, & Helms, 1998; Helms, 1990; Milliones, 1976, 1980; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). Several models and measures of racial identity within African Americans have been proposed (e. g., Cross, 1971, 1991; Parham & Helms, 1981; Sellers et al., 1998). However, their general focus has been on two periods of the life course, childhood and emerging adulthood, overlooking, for the most part, the developmental periods of early and middle adolescence (Phinney, 1990). Consequently, theoretical conceptualizations of African American racial identity during early and middle adolescence as well as empirical tools for assessing African American racial identity during these developmental periods are rare. To address this oversight, the current study presents a new measure of racial identity specifically for African American adolescents: The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen (MIBI-t). This measure consists of 7 subscales representing the three cross-situationally stable dimensions (Centrality, Regard, and Ideology) of the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI; Sellers, et al., 1998). Information supporting the reliability and validity of this new measure is presented.

The Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI)

The MMRI is grounded in identity theory (Stryker, 1987), which argues that each individual has a number of hierarchically ordered identities (e. g., racial, gendered, and vocational), and that within this hierarchy one identity can be more important to an individual than another. Building on this, the MMRI asserts that the degree to which race is important to individual self-concept has both situationally specific and cross-situationally stable components that interact to determine how race influences behavior both in specific situations and across situations. In addition, the MMRI considers the unique historical and cultural contexts associated with African American group membership. Emphasizing that there is no singular definition of African American culture, the model identifies a set of culturally relevant beliefs about what it means to be African American, allowing each individual to subjectively define what it means to them to be a member of the Black community, placing no value judgments regarding healthy or unhealthy identities. Thus, the MMRI proposes a conceptual framework for understanding the heterogeneity in African Americans’ attitudes regarding the importance and meaning that they attach to race (Sellers et al., 1998).

Within the model, four dimensions of identity are proposed: Salience, Centrality, Regard, and Ideology. Racial Salience refers to the extent to which race is relevant to the self-concept at a particular point in time or in a particular situation. Unlike the other three dimensions, Salience is likely to change as a function of context. In contrast, racial Centrality refers to the extent to which an individual normatively emphasizes racial group membership as part of their overall self-concept. The third dimension, racial Regard refers to whether an individual feels positively or negatively about African American group membership and is divided into two sub-dimensions: Public and Private. Public regard is defined as the extent to which an individual feels that others view the African American community in a positive or negative manner. Private regard is defined as the extent to which an individual feels positively or negatively toward the African American community as well as how she/he feels about being a member of this community. The final dimension, racial Ideology, refers to one’s philosophy about the ways that members of the African American community should act. It is comprised of four subcomponents: Nationalist, Oppressed Minority, Assimilationist, and Humanist (Sellers et al., 1998). The Nationalist Ideology emphasizes the uniqueness of being African American and is characterized by the support of African American organizations and preference for African American social environments. The Oppressed Minority Ideology emphasizes the similarities between African American’s experiences and those of other oppressed minority groups. Assimilationist Ideology emphasizes the similarities between African American and mainstream American society. Humanist emphasizes the similarities among all people regardless of race.

The Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) was originally created to operationalize the three cross-situationally stable dimensions (Centrality, Regard, and Ideology) of the MMRI (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). The contextually-dynamic nature of salience makes it inappropriate to use a questionnaire to operationalize the dimension. As such, the MIBI consists of a Centrality scale, two Regard subscales and four Ideology subscales. Using exploratory factor analysis and correlational analyses, Sellers and colleagues reported evidence of the MIBI’s construct and concurrent validity within a college sample (Sellers et al., 1997). Over the years, several studies have related various subscales of the MIBI to a number of important phenomena for African American college students and young adults, including experiences with racial discrimination (Sellers, Linder, Martin, & Lewis, 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Shelton & Sellers, 2000); academic outcomes (Chavous, Bernat, Schmeelk-Cone, Caldwell, Kohn-Wood, & Zimmerman, 2003; Rowley, 2000; Sellers, Chavous, & Cooke, 1998); and psychological well-being (e.g. Caldwell, Kohn-Wood, Schmeelk-Cone, Chavous, & Zimmerman, 2004; Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998; Sellers et al., 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). To date, all of the published studies that have assessed the psychometric properties of the MIBI have done so with either a college student or adult community sample (Cokely & Helms, 2001; Sellers et al., 1997; Walsh, 2001).

The Need for a Measure of Racial Identity for Adolescents

Although the majority of research utilizing the MIBI has been conducted with college student or adult community samples, two studies have used the Centrality and Regard subscales of the MIBI with African American high school students (Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone & Zimmerman, 2003). Although both studies reported information regarding the internal consistency of the Centrality and Regard subscales, neither study provided information regarding the construct validity of the subscales within their sample. We are unaware of any study that has assessed the construct validity of the MIBI with an adolescent sample. Furthermore, we are not aware of any research that has explored the psychometric properties of the Ideology subscales with early or middle adolescents. This may be because many of the items in the Ideology subscales are beyond the reading and conceptual comprehension of most teens. For instance, many early and middle adolescents are unfamiliar with such concepts as follows: “Afrocentric values”; “political and economic goals”; “injustice and indignities”; and “Black liberation”. These are all terms that can be found in items within the Ideology subscales of the MIBI.

There are also important developmental differences between college students (emerging adults) and adolescents that call into question the appropriateness of a single measure of racial identity for both age groups (see Arnett, 2000; Arnett & Taber, 1994; Eccles, Templeton, Barber, & Stone, 2003). Early and middle adolescents are in a completely different social environment than most college students and other emerging adults. Not surprisingly, issues of racial awareness also play out differently for individuals at different stages of adolescence. For college students, a salient task is learning to live away from home for the first time (Ethier & Deaux, 1994). Many of the experiences that influence their racial identity development involve in some way the novelty of their circumstances and occur among individuals that have little or no connection to their childhood. Although many of the racial tensions that teens experience in early and middle adolescence are also the result of changing interactions with peers (Tatum, 1997). Teens typically live in a very different social ecology than college students. While the struggle for autonomy is an important developmental life task for all stages of adolescence, teens in early and middle adolescence are doing so under the structure of living at home while being supervised by their parents or other adult authority figures. Although peers play an increasingly important socializing role, for most teens in early and middle adolescence, the family is still the primary racial socializing agent (Coard & Sellers, 2005; Hughes, Rodriquez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006). In sum, the developmental differences in reading ability and social experiences between teens in middle and high school (early and middle adolescence) and college students (emerging adults) suggest the need for separate measures of racial identity that are age appropriate.

Issues to be Considered in Developing the MIBI-t

In developing a specific measure of the MMRI for use with early and middle adolescents, it is important that the constructs that are foundational to the model are consistent with adolescent experiences. In developing the MMRI, Sellers and colleagues reviewed primarily the literature on adult identity development (Sellers et al., 1998). This being the case, it is possible that the dimensions of Centrality, Regard, and Ideology are beyond the cognitive and social capacities of early and middle adolescents. Cross (1991) noted that much of the early work on African American self-hatred was based on the inappropriate extrapolations of findings from studies conducted with young children to the psychological functioning of adults across the life span. In order to avoid the converse of this mistake, there must be clear evidence that adolescents understand the constructs underlying the MMRI and that these constructs are consistent with their own experiences in the world. This evidence should be distinct from their performance on the new measure. In addition, the adolescents’ performance on the new measure should correspond to the underlying structure proposed by the conceptual framework that it proposes to operationalize. In other words, it is important to have evidence of the validity of the conceptual model within the proposed population, before one can assess the validity of an instrument purporting to operationalize the conceptual model with the proposed population.

It is also important that a developmentally-appropriate measure of racial identity for adolescents retain its underlying factor structure across various theoretically important subgroups so that the measure can be used to appropriately investigate group differences in racial identity. Comparing mean differences on a measure across groups assumes that the underlying structure of the measure is similar or invariant across the groups. Too often this assumption is never tested. One important subgroup difference relevant to adolescence is developmental stage. Some researchers have noted important physical and experiential milestones in middle adolescence that make the formation of a racial identity particularly paramount for African American adolescents (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2000; Tatum, 1997). For instance, recent research by French and colleagues (2006) suggests that there may be important developmental differences between early and middle adolescents in the trajectory of ethnic identity change over time (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006). However, since the authors did not report whether the underlying structure of their measure demonstrated consistency across early and middle adolescents, it remains unclear whether differences found between these groups represent true developmental differences or are a function of age differences in the underlying structure of the measure. In making the argument that there needs to be a specific measure of racial identity for early and middle adolescents, it is important that the measure demonstrate similar levels of construct validity for both early and middle adolescents.

Gender is another important subgroup difference that an adolescent-specific measure of racial identity should be able to investigate. Although a number of scholars have discussed the ways in which race and gender intersect to influence the lives of African American men and women (e.g., Brown, 2000; Cole & Stewart, 2001; Collins, 1990; Sidanius & Veniegas, 2000), there is surprisingly little research on gender differences in racial identity. Although there have been studies that have found gender differences in other measures of racial identity (e.g., Munford, 1994; Plummer, 1995), Rowley and colleagues (2003) conducted the only investigation of gender differences using the MIBI (Rowley, Chavous, & Cooke, 2003). Using both variable-centered and person-centered approaches to investigate gender differences in racial ideology in a sample of 724 African American college students, they found no evidence of gender differences in racial ideology. There have been no other studies that have examined gender differences in the other MIBI subscales. In addition, we are unaware of any study that has tested gender invariance in any measure of African American racial identity. As such, it is unknown whether gender differences in race-related experiences such as racial socialization and racial discrimination lead to differences in the structure of racial identity for African American men and women.

Finally, it is important that a measure designed specifically for adolescents is as efficient as possible in the number of items used to assess the underlying constructs. The length of a measure often impacts both its frequency of use and its performance in a number of ways. First, adolescents have relatively short attention spans as compared to older adults. As a result, adolescents are more likely to lose focus when completing long measures. Such a loss of focus can have an adverse impact on the reliability of the measure. Second, often researchers are forced to choose racial identity measures as well as exclude certain subscales or shorten other scales based on their length as opposed to other substantive criteria such as the measures’ psychometric properties or their theoretical foundation. Such practical decisions result in significant gaps in our knowledge and undermine the richness of many of our multidimensional and multifaceted conceptualizations of racial identity. As a result, the MIBI-t uses as few items as possible to measure the various constructs in the MMRI.

The Current Study

In the present study, we investigated the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen (MIBI-t) in a sample of African American middle and high school students. By doing so, we also assessed whether the MMRI represents a valid framework for conceptualizing racial identity among African American adolescents in two ways. First, we determined whether adolescents understand and experience their racial identities in ways that are consistent with the dimensions of the MMRI. Second, we tested whether the adolescents’ responses to the MIBI-t adhere to the underlying factor structure proposed by the MMRI. In addition, we examined the appropriateness of the MIBI-t for different subgroups of adolescents by testing whether the underlying structure of the measure is equivalent across grade level and gender. In addition, we explored possible gender and grade-level differences in the means of the various subscales of the MIBI-t. We hypothesized that the MIBI-t would demonstrate evidence of an internal structure consistent with the structure of the MMRI. While we also expected that the structure would be invariant across age and gender, we had no a priori predictions regarding mean differences in the subscales across subgroups.

We assessed the predictive validity of the MIBI-t in the present sample by examining its relationship to subsequent race relevant behavior. Consistent with identity theory (Stryker & Serpe, 1982), findings from previous research suggests that African Americans who identify strongly with their group are more likely to engage in race-related activities such as seeking knowledge about African American culture and participating in African American organizations (Baldwin, Brown, & Backley, 1990). Previous research with the adult MIBI supports these findings, linking higher scores on the Centrality and Nationalist subscales with greater enrollment in Black Studies courses, greater number of African American friends, and greater social contact with African Americans in general (Sellers et al., 1997). Thus, we predicted that youth within our sample who score higher on the Centrality and Nationalist subscales will also report engaging in race-related conversations more frequently and have more social contact with other African Americans than their peers who score lower on the two subscales.

Method

Participants

The current sample consisted of 489 African American adolescents living in a small city in the Midwest of the United States who were recruited to participate in a longitudinal, community-based study of African American racial identity. The study consisted of three cohorts of students. Two hundred eighty-nine students were recruited in the first cohort, 131 were recruited in the second cohort, and 69 were recruited in the third cohort.

Students were recruited from 6 middle schools and 4 high schools. The specific grade breakdown of the present sample was as follows: 33% 7th grade; 33% 8th grade; 18% 9th grade; and 16% 10th grade. Girls (N=289) comprised 60% of the sample. Participants ranged in age from 12 to 16 years with a mean age of 13.7 years (SD = 1.20). Although students were initially identified as African American through school records, 397 (81.2%) participants self-identified as Black/African American; 83 (17%) participants indicated that they were of mixed African American heritage such as African American/Caucasian or African American/Hispanic; and 9 (1.8%) participants indicated that they were from another ethnic background such as Black/African. Family information was also obtained from a parent or primary caregiver of the participant. Median family income for the sample as reported by parents of the participants was between $20,000–40,000. Approximately 44% of the parents reported having at least some college education or an associate’s degree and 25.7% reported having a bachelors or graduate degree.

Procedure

Initial contact information was obtained from the school district for students in grades 7 through 11 who were identified by school records as being African American. The parents of each of the African American students were contacted via mail and asked to participate in the study. Those families neglecting to respond to this initial contact were then contacted by telephone and asked to participate in the study. Those parents or guardians agreeing to participate over the phone were asked to mail in an informed consent form. Prior to participation, teen assent was also obtained. Across the three years of recruitment (2002–2004), the households of 742 adolescents were contacted, with a total of 546 agreeing to participate for a response rate of 74%. The current sample (N = 489) was drawn from this pool and is comprised of 8th–10th graders for whom complete data were available on the target variables. The majority of adolescents completed the questionnaire during a session after school in a classroom setting with approximately 30 other participants. Alternative sites such as community centers and local libraries were also used to administer the questionnaire in small groups. The questionnaires consisted of a number of measures of demographic background, academic experiences and attitudes, race-related experiences, and mental health outcomes. The order of the measures was counterbalanced. On average, adolescents took 40–50 minutes to complete the questionnaires. Adolescents received a gift certificate for the local mall of $20 or $30 depending on whether they had participated in a previous research project.

The city in which the study was conducted has a population of approximately 110,000 people. African Americans comprise roughly 9% of the city population. The median household income for the city is above the national average at $46,299. Eighteen percent of the school district’s students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. Although the median family income for African Americans in the city surpasses the national average (median income $30,000–$39,000), there is significant variation across the distribution within the community, with incomes ranging from less than $10,000 to more than $130,000.

Measures

Item selection for the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen

Prior to MIBI-t construction, eighteen African American adolescent boys and girls (grades 7 through 10) participated in four focus groups led by an African American adult facilitator. Focus group participants were distinct from those included within the current study and did not complete paper and pencil forms of the MIBI-t. Thus, focus group participants were not included within the current, quantitative sample. The objectives of the focus groups were to (1) gather information regarding age-appropriate language that could be used in item creation; and (2) assess the appropriateness of individual items from the adult MIBI for an adolescent audience. To this end, a protocol was developed in order to offer continuity between groups and guide discussion in an orderly manner. Following an introductory segment in which the goals and the rules of the focus group were explained, teens were asked to respond to the statement, “What does being African American mean to you?” This open discussion at the beginning of each group offered insight into how teens defined being African American before entering into a more structured discussion of the MMRI. Next, youth were given the definition of a dimension or sub-dimension of the MMRI and asked to explain what the construct meant in their own words using illustrative examples from their own lives. Once this discussion had been completed, the facilitator engaged participants in a discussion of specific items drawn from the various subscales of the adult MIBI. After allowing teens to discuss each item, participants were asked questions designed to assess their understanding of each item as well as elicit information regarding age appropriate language that could be used to develop an alternative item.

In evaluating the MIBI items, youth in the focus groups indicated consistent comprehension of the vocabulary and concepts used in the Centrality and Private Regard subscales. However, they reported more difficulty with some of the items from the Public Regard subscale and all of the items from the Ideology subscales. As a result, the original set of Centrality and Private Regard items used in the adult MIBI, and the subset of MIBI Public Regard items that participants demonstrated the ability to understand were incorporated into the preliminary adolescent measure. Given the difficulty that participants demonstrated in understanding the Ideology items drawn from the adult MIBI, information obtained from the focus group sessions was used to develop a new set of Ideology items. The resulting preliminary measure consisted of a pool of 63 items representing the seven cross-situationally stable dimensions of the MMRI (Centrality, Public Regard, Private Regard, Nationalism, Assimilation, Oppressed Minority and Humanism).

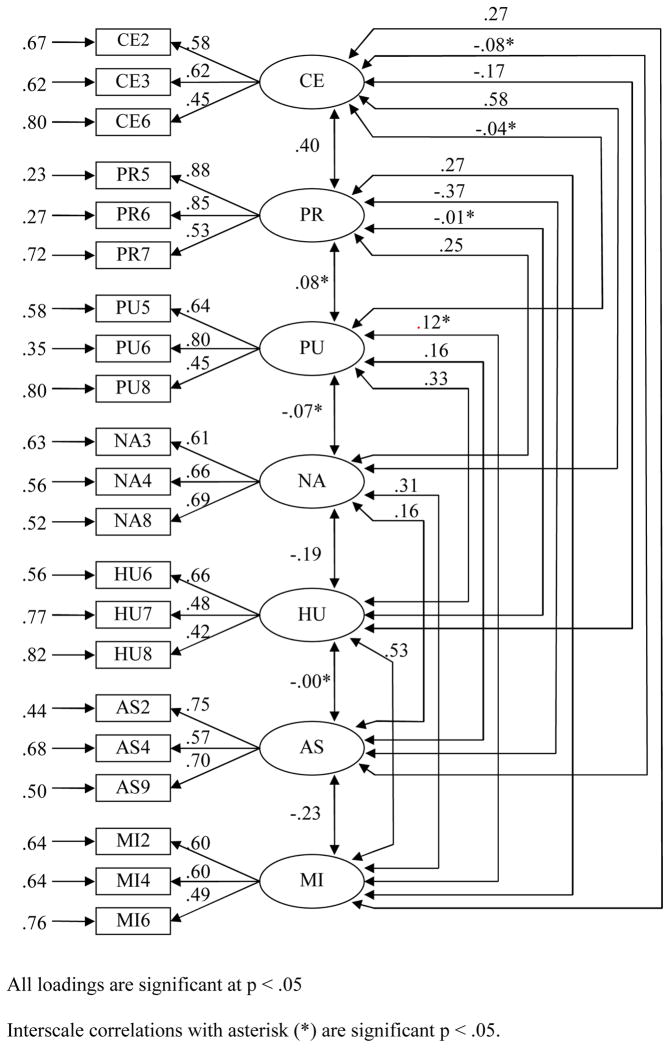

These 63 items were administered to participants in the current, quantitative study. Seven exploratory factor analyses using Principal Components as the method of extraction were conducted for each of the seven subscales. Items that loaded less than .30 on the proposed factor were discarded. The remaining items were then included in a single confirmatory factor analysis with seven interrelated factors representing the seven subscales of the MIBI. Each item was forced to load on only one of the factors. Error terms for each item were allowed to covary with other items in the same subscale but not items outside of the subscale. Items that yielded an R2 of .20 were retained for future consideration. Finally, from this pool, we selected 21 items (3 items per subscale) for inclusion in our final model. In selecting the items, we considered issues of face validity, clarity, as well as construct coverage. We selected a 21-item model in order to generate the most parsimonious model solution possible while still generating subscales that could be identified in structural equation models. A confirmatory factor analysis similar to the one described above was conducted on the 21-item model. The fit of the data to the model was strong (χ2 (168, N = 489) = 331.97, p < .01; RMSEA = .04; NNFI = .93; CFI = .94). We refer to these 21 items as the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen (MIBI-t).

Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-t

The MIBI-t consists of seven subscales comprised of three items each (see Appendix A for the complete set of MIBI-t items). Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Respondents’ scores are averaged across the three items to generate a composite score for each subscale (see Appendix A for the list of items). The Centrality scale (α = .55) assesses the extent to which race is an important part of an individual’s identity. A higher score is indicative of the individual feeling that race is a more central identity. The Private Regard subscale (α = .76) measures the extent to which an individual feels positive towards other African Americans and being African American. The Public Regard subscale (α = .66) measures the extent to which the individual feels that other groups feel positively or negatively toward African Americans. Higher scores on the Regard subscales indicate more positive feelings towards African Americans. Four ideology subscales were also generated to assess how individuals feel that African Americans should act. The subscales include: Assimilationist (α = .70), Humanist (α = .50); Minority (α = .57); and Nationalist (α = .70). Higher scores represent greater endorsement of the Ideology.

It should be noted that concise scales with lower alphas may be as internally consistent as longer scales if the inter-item correlations are adequate (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991). Some of the Cronbach alphas for MIBI-t subscales were less than .70, suggesting that the subscales may be unreliable. Using the inter-item correlations for each subscale1, the Spearman-Brown Formula2 was used to calculate the estimated Cronbach alpha if the subscales contained the same number of items per subscale utilized within the original MIBI, with the same inter-item correlations that were found in the present study. The estimated Chronbach alphas are as follows: Centrality (8 items; α = .78); Private Regard (6 items; α = .87); Public Regard (6 items; α = .79); Nationalist (9 items; α = .87); Assimilationist (9 items; α = .88); Humanist (9 items; α = .75); Minority (9 items; α = .80). These coefficients all exceed the convention of .70, as well as those Cronbach alpha coefficients generated by previous research using the original MIBI with both adult (Sellers et al., 1997) and adolescent populations (Rowley et al., 1998).

Interracial contact

Each students’ amount of interracial contact was assessed using three items designed to indicate the racial composition of each participants’ neighborhood, school, and classroom (α = .54). For instance, participants were asked to respond to the following question, “Which best describes the racial make up of the people in your neighborhood?” Responses were indicated using a 5-point scale ranging from “almost all people from other races” to “almost all Black people”. Scores were summed across the three items. Higher scores represent greater contact with African Americans.

Racial Conversations

The frequency of race-related conversations was assessed using a three-item index designed to tap how often participants engaged in conversations about being African American with their peers. The three items consist of (1) How often in the past year have you talked about things related to race, racism, or being Black with your best friend? (2) How often in the past year have you talked about things related to race, racism, or being Black with other close friends? (3) How often in the past year have you talked about things related to race, racism, or being Black with other people in your school? Participants responded to each of the items using an 8-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = more than twice a week to 8 = I have not talked about race. The set of items demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .80). Higher scores indicate engaging in more conversations about racial issues.

Results

In order to investigate the content validity of the MIBI-t, a series of confirmatory factor analyses were conducted using LISREL 8.54. The fit of confirmatory factor analysis is judged by interpreting multiple indicators. To be considered a good fit, the Chi-Square statistic should be small, the RMSEA should fall near .05, and the NNFI and CFI should be close to “1”. Consistent with the MMRI, we proposed a seven-factor model representing each of the subscales of the MIBI. Each factor had three items loading on the factor and each item loading on only one factor. The factors were allowed to correlate with one another. None of the error terms for the items were allowed to correlate with each other. Using this model, we tested the fit of the data for the entire sample. The goodness of fit indices indicated a good fit to the data for the model (see Table 1). In order to determine whether the overall fit of the MIBI-t for the entire sample was simply a function of the fact that data from cohort 1 was used to determine the 21 items that went into the final model of the MIBI-t, we ran a confirmatory factor analysis only on the data from cohorts 2 and 3 combined. The analyses yielded a good fit to the data for the two combined cohorts, replicating the adequacy of the model in a different sample of African American adolescents (χ2 (168, N = 200) = 220.15, p < .01; RMSEA = .04; NNFI = .94; CFI = .95). Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics and inter-scale correlations for the entire sample.

Table 1.

Goodness-of-Fit Indicators of Models for MIBI-t Overall Fit and Tests of Invariance (n = 489)

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2diff | NNFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | 334.97** | 168 | .93 | .94 | .04 | |

| Grade Level | ||||||

| Model 1 | 494.78*** | 336 | .93 | .94 | .04 | |

| Model 2 | 520.91*** | 357 | 26.13 | .93 | .94 | .04 |

| Model 3 | 543.93*** | 378 | 49.15 | .93 | .94 | .04 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Model 1 | 514.17** | 336 | .92 | .94 | .05 | |

| Model 2 | 558.85** | 357 | 44.68** | .91 | .93 | .05 |

| Model 3 | 587.16** | 378 | 72.99** | .92 | .92 | .05 |

p < 01,

p < .001

Table 2.

Interscale Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-t(een) Subscales (n = 489)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Centrality | – | ||||||||

| 2. Private Regard | .35** | – | |||||||

| 3. Public Regard | .01 | .12** | – | ||||||

| 4. Nationalist | .35** | .20** | −.04 | – | |||||

| 5. Oppressed Minority | .16** | .21** | .12** | .19** | – | ||||

| 6. Assimilationist | −.08 | −.31** | .12* | .11* | −.17** | – | |||

| 7. Humanist | −.14** | .01 | .20** | −.12* | .31** | .03 | – | ||

| 8. Interracial Contact | .27** | .13** | −.02 | .12** | −.09* | .04 | −.14** | – | |

| 9. Racial Conversations | .19** | .08 | −.07 | .20** | .19** | −.11* | −.07 | .01 | – |

| Mean | 3.85 | 4.66 | 3.32 | 3.26 | 4.10 | 1.81 | 3.74 | 2.42 | 4.04 |

| SD | .80 | .58 | .90 | .94 | .72 | .90 | .85 | .84 | 2.10 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Group Differences in the Structure of the MIBI-t

In order to test whether the MIBI-t had the same underlying structure across different subgroups of our data, we used a procedure advocated by Byrne (2004) to test for structural invariance in models across groups. For each group comparison, we tested three increasingly restrictive structural equation models that compared the fit of the data across subgroups. The first model allowed item loadings and covariances to differ significantly across groups. This model was considered the baseline model since it was the least restrictive. Baseline parameters were estimated using data from both subgroups and thus, yield the best fit to the data. The second model was constrained against any significant group differences in item factor loadings. The fit of this model was compared to the baseline model to determine whether any of the items loaded differently onto the factors across the groups. The fit of the second model was then compared to the baseline model in order to determine whether item loadings were invariant across the two groups (Byrne, 2004). The third model constrained both the item loadings and the covariances between factors to be equal across groups. The fit of this model was compared to the fit of the baseline model to determine whether or not both the item loadings and the covariances were invariant across groups. Traditionally, differences in the Chi Square statistics for the two models have been used to determine differences in model fit, but recently a number of authors have noted the limitations of the Chi Square statistics for larger samples (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Mantzicopoulos, French & Maller, 2004). Cheung and Rensvold (2002) have called for comparing model differences in the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) as a way of testing model differences in fit. They argue that the difference in CFI values between the baseline model and the comparison model should not exceed .01 for the two models to be considered invariant.

With regard to grade level, the baseline model (no constraints) yielded an adequate fit to the data (see Table 1). Model 2 (constraining loadings) yielded a similar fit to the data as the baseline model, suggesting that the item loadings were invariant across grade level. Finally, model 3 (constraining both loadings and covariances) also yielded a similar fit as the baseline model, suggesting that the underlying structure of the MIBI-t is the same for both the middle school and high school students in the sample.

A similar procedure was used to test gender differences in the underlying structure of the MIBI-t. The baseline model for gender also yielded acceptable fit indices (see Table 1). Comparisons of the fit of Model 2 to the baseline model indicated that the underlying structure of the MIBI-t is invariant across gender with respect to the way in which the items load on the factors. However, when both loadings and covariances were constrained, invariance was not as strong. Specifically, the CFI values for models 1, 2, and 3 were as follows: .9355; .9270; and, .9243. The difference in CFI values between models 1 and 2 does not exceed .01, thus invariance in factor loadings can be assumed. However, the difference between Models 1 and 3 equals .0112. Thus, model invariance is not as strong for gender as it is for cohort and grade when both factor loadings and covariances are constrained; but the CFI difference does not grossly exceed .01. Additional analyses indicate that the covariances between Humanism and Centrality, and Humanism and Nationalism differed across male and female participants.

Grade and Gender Mean-Level Differences in MIBI Subscale

Seven 2 (grade level) × 2 (gender) ANOVA were conducted for each MIBI-t subscale to examine grade level and gender differences in mean scores of the MIBI-t. A Bonferroni Correction was used such that p values had to be smaller than .007 (.05/7 = .007) in order to reach significance. A significant main effect for grade level was found for the Nationalist subscale. Middle and high school students reported significantly different levels of the Nationalist ideology, F(1, 489) = 21.64; p < .001, such that high school students reported higher Nationalist (Mean = 3.54 vs. 3.12) scores than middle school students. A significant gender main effect was also found for the Assimilationist ideology, F(1, 489) = 12.35; p < .001, such that girls reported lower Assimilation scores than boys (Mean = 1.70 vs. 1.99). No significant grade level × gender interactions were found for any of the subscales.

MIBI-T Subscales and Race-Relevant Phenomena

Pearson-product correlations were obtained for the MIBI-t subscales and race-related phenomena as evidence of the concurrent validity of the MIBI-t. With respect to interracial contact, higher levels of Centrality (r = .27, p < .01), Private Regard (r = .13, p < .01), and the Nationalist ideology (r = .12, p < .01) were associated with greater African American contact. Conversely, higher levels of the Humanist (r = −.14 p < .01) and Minority ideologies (r = −.09, p < .05) were associated with less African American contact. With regard to conversations about race, significant correlations were found such that higher scores on the Centrality (r = .19, p < .01) and Nationalist (r = .20, p < .01) subscales were associated with more frequent conversations about race, while higher scores on the Assimilationist (r = −.11, p < .05), and Minority (r = .19, p < .01), subscales were associated with less frequent conversations.

Discussion

The findings indicated that the new proposed MIBI-t demonstrates evidence of construct validity within our sample of African American early and middle adolescents. Specifically, findings from a confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the internal structure of the MIBI-t is consistent with the conceptual framework proposed by the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity. Although mean grade level and gender differences were found for some of the subscales, the underlying structure of the MIBI-t was reasonably invariant across both grade level and gender. Thus, the MIBI-t seems to be appropriate for use with both early and middle adolescents as well as African American girls and boys. The present results also suggest that the subscales of the MIBI-t are related to race-relevant phenomena in ways that are consistent with what one would expect, given the constructs that they measure. These results provide limited evidence of the predictive validity of the MIBI-t within our sample.

Findings from our initial focus groups suggested that most early and middle adolescents have an understanding of the constructs that underlie the MMRI. The fact that the adolescents in the focus groups were able to relate the constructs to events and experiences in their own lives provides some evidence that the MMRI is a valid framework for conceptualizing racial identity in African American early and middle adolescence. With the exception of the Minority ideology in a couple of the youngest participants, teens in the focus group demonstrated little difficulty in articulating the meaning of each of the MMRI dimensions and sub-dimensions. It would be interesting to see whether African American adolescents in more racially heterogeneous environments would have less difficulty with the conceptualization of the Minority ideology. The fact that a relatively small number of teens participated in our focus group and that the sample was not representative suggests the need for further studies before any definitive conclusions can be made. When the findings from the focus group are combined with the findings from our quantitative analyses, however, a more compelling case can be made for the validity of the MMRI as a conceptual framework for early and middle adolescents. By definition, evidence of the construct validity of the MIBI-t is also evidence of the validity of the MMRI as a conceptual framework for African American teens in early and middle adolescence. The validity of the construct (MMRI) within a particular sample is a necessary condition of construct validity of any measure of a construct (MIBI-t) within a particular sample. Thus, the fact that African American teens in our sample responded to the items in the MIBI-t in a manner that was consistent with what was proposed by the MMRI is not only evidence of the construct validity of the MIBI-t as a measure of the MMRI in the present sample, but also further evidence of the appropriateness of the framework for adolescents.

Our analyses also provide some evidence that the internal structure of the MIBI-t is invariant across grade level. In particular, the results indicated that not only do the 21 items load similarly on the subscales for the early and middle adolescents, but that the relationship between the subscales does not differ for the two grade levels. This finding suggests that early and middle adolescents view their racial identity in a similar manner. This high level of consistency in both the relationship between scales and the few mean level differences in scores suggests a relatively high level of stability in racial identity across these two earlier stages of adolescence. This finding of stability in racial identity across early and middle adolescence is inconsistent with theorists who suggest that early and middle adolescent is a time when the construction of a racial identity is a developmentally-appropriate life task (e.g., Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001; Tatum, 1997). In one of the few empirical studies to directly address this issue, French and colleagues (2006) reported findings that are both consistent and contradictory to ours (French, et al., 2006). On the one hand, they also reported data in which there were no mean differences in racial self-esteem between African American early and middle adolescents. From a cross-sectional perspective, the data from these two studies suggest that racial identity attitudes are somewhat stable between early and middle adolescences. On the other hand, based on their longitudinal analyses, French and colleagues (2006) also reported a trend in both the early and middle adolescents in which there was an increase in racial self-esteem over a three-year period. These data suggest that African Americans adolescents’ racial identity attitudes do change over time. Given the fact that the early adolescents in their study ended up with higher racial self-esteem at year three than the middle adolescent sample had in year one calls into question whether the longitudinal trend found is the result of a normative developmental process or an artifact of the study. Future research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made. It is important that further research also assess the invariance in the structure of the measure of adolescents’ racial identity over time.

Our findings also indicated that the MIBI-t is invariant across gender with respect to the way in which items loaded on the proposed factor structure. The fact that MIBI-t is invariant with respect to the item loadings suggests that the scale is measuring a similar construct for both boys and girls and that it is appropriate to use it to compare mean differences between the genders. The fact that the scale did not meet our standards for invariance with respect to the covariance between the subscales indicates that the two groups differ with respect to how the subscales are correlated. Further research is needed to determine the nature of this difference and what aspect of being African American male or female accounts for this difference.

Although the underlying structure of the MIBI-t was invariant across grade level and gender, there were some interesting group differences in the mean levels of some of the MIBI scales. For instance, high school adolescents reported attitudes suggesting greater emphasis on Nationalism than adolescents in middle school. This greater emphasis on the uniqueness of being African American by older adolescents may be a function of contextual differences between the high school environment and the middle school environment or they may be the result of greater cognitive and social development within the adolescent, or some combination of the two (Brown & Bigler, 2005). Further research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made regarding the nature of these findings. Unlike previous research on gender differences in African American college students, the present study found significant differences between African American adolescents in Assimilationist attitudes. The finding of higher scores on the Assimilations subscale is consistent with Tatum’s (1987) research, which suggests that African American adolescent boys may find greater acceptance among European American middle school and high school mates than African American girls as a result of boys participating in socially-valued activities such as sports. This greater acceptance among European American classmates may result in greater endorsement of an Assimilation ideology. Further research is needed before definitive conclusions can be made.

The results of the correlations among the MIBI-t subscales and measures of interracial contact and conversations about race provide preliminary evidence of the predictive validity of the MIBI-t. As was predicted, teens who scored higher on the Centrality, Private Regard, and Nationalist subscales reported having more contact with African Americans. Higher scores on the Humanist and Oppressed Minority subscales showed an inverse pattern of relationships. Interestingly, the Assimilation subscale was unrelated to contact with African Americans. Findings related to racial conversations mirror these patterns within the context of racial Centrality and Nationalism. The overall pattern of results is similar to those reported by Sellers and colleagues (1997) in their initial validation study of the MIBI with African American college students (Sellers et al., 1997). The fact that in the present study we examine the relationship between MIBI-t scores and later measures of race relevant phenomena strengthens the case for predictive validity.

The present findings not only provide some evidence of the construct and predictive validity of the MIBI-t, but they also represent an important initial step in generating a life span model of racial identity that can be empirically tested. Although some leading racial identity researchers have proposed theories about the ways in which the content of individuals’ racial identity attitudes may develop over the life span (e.g., Cross & Fhagen-Smith, 2001), the measures used to operationalize the models have typically been designed and validated with adult and emerging adult populations. As a result, it is impossible to track the proposed developmental changes in the content of individuals’ racial identity attitudes across the life course using these measures without introducing potential measurement error resulting from the use of measures that were not designed to be used with younger adolescents. The very few studies that have attempted to assess changes is racial identity development across the life span have focused on measures of identity process (French et al., 2006; Seaton, Scottham, Sellers, 2006; Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006). The use of both the MIBI-t and the MIBI will allow for the investigations of systematic differences in the content of individuals’ racial identity across the life span. To be sure, further research is needed to assess the level of concordance between the MIBI-t and MIBI before we can track racial identity development from adolescence through adulthood. Nonetheless, the development of an empirically-valid measure of the MMRI for African American teens in early and middle adolescence is a crucial step in the process.

In conclusion, the present findings represent an important addition to the racial identity literature. Although more research is needed replicating the present findings with other samples, the present study represents promising initial results regarding the potential of a new measure of racial identity for African American adolescents. Another contribution of the development of the MIBI-t is that it is a significantly shorter measure than the original MIBI (21 items compared to 56 items). This should make the MIBI-t much more user-friendly. The 21-item MIBI-t provides an efficient and economical alternative for researchers. As such, we hope that the development of the MIBI-t will provide the impetus for more systematic investigation of the racial identity attitudes of African American youth.

Figure 1.

Measurement Model, including loadings and covariances for each MIBI-t item.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 5 NIMH 5 R01 MH61967-02) and the National Science Foundation (BCS-9986101). The second author is the Principal Investigator for both grants. We thank the African American Racial Identity lab group for their help with data collection.

Appendix A

Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity-teen

Centrality

I feel close to other Black people.

I have a strong sense of belonging to other Black people.

If I were to describe myself to someone, one of the first things that I would say is that I’m Black.

Private Regard

I am happy that I am Black.

I am proud to be Black.

I feel good about Black people.

Public Regard

Most people think that Blacks are as smart as people of other races.

People think that Blacks are as good as people from other races.

People from other races think that Blacks have made important contributions.

Nationalism

Black parents should surround their children with Black art and Black books.

Whenever possible, Blacks should buy from Black businesses.

Blacks should support Black entertainment by going to Black movies and watching Black TV shows.

Humanism

Being an individual is more important than identifying yourself as Black.

Blacks should think of themselves as individuals, not as Blacks.

Black people should not consider race when deciding what movies to go see.

Assimilation

It is important that Blacks go to White Schools so that they can learn how to act around Whites.

I think it is important for Blacks not to act Black around White people.

Blacks should act more like Whites to be successful in this society.

Oppressed Minority

People of all minority groups should stick together and fight discrimination.

There are other people who experience discrimination similar to Blacks.

Blacks should spend less time focusing on how we differ from other minority groups and more time focusing on how we are similar to people from other minority groups.

Likert Response Scale is as follows: (1) Really Disagree; (2) Kind of Disagree; (3) Neutral; (4) Kind of Agree; (5) Really Agree

Footnotes

The average inter-item correlations for MIBI-t (3 item) subscales are as follows:

Centrality = .31

Public Regard = .39

Private Regard = .53

Nationalist = .43

Assimilationist = .44

Oppressed Minority = .31

Humanist = .25

The Spearman Brown Formula is as follows:

Alpha rk = kr/[1 + (k−1) r]

Where k = number of items and r = average correlation among the items

Contributor Information

Krista Maywalt Scottham, Bates College.

Robert M. Sellers, University of Michigan

Hòa X. Nguyên, University of Michigan

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Taber S. Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:517–537. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ, Howard C. Race-related socialization, motivation, and academic achievement: A study of Black youths in three-generation families. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:134–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TL. Gender differences in African American students’ satisfaction with college. Journal of College Student Development. 2000;41:479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Bigler RS. Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development. 2005;76:533–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlew AK, Bellow S, Lovett M. Racial identity measures: A review and classification system. In: Dana RH, editor. Handbook of cross-cultural and multicultural personality assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:272–300. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Kohn-Wood LP, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Chavous TM, Zimmerman MA. Racial discrimination and racial identity as risk or protective factors for violent behaviors in African American young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:91–105. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014321.02367.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavous TM, Bernat DH, Schmeelk-Cone K, Caldwell CH, Kohn-Wood L, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity and academic attainment among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2003;74:1076–1090. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness of fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Coard S, Sellers RM. African American families as a context for racial socialization. In: McLoyd V, Hill N, Dodge K, editors. African American family life: ecological and cultural diversity. New York: Guildford Press; 2005. pp. 264–284. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER, Stewart AJ. Invidious comparisons: Imagining a psychology of race and gender beyond differences. Political Psychology. 2001;22:243–308. [Google Scholar]

- Collins P. The meaning of motherhood in Black culture and Black mother/daughter relationships. SAGE: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women. 1987;4(2):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. The Negro-to-Black conversion experience. Black World. 1971 July;:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr, Fhagen-Smith P. Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In: Jackson B, Wijeyesinghe C, editors. New perspectives on racial identity development: A theoretical and practical anthology. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001. pp. 243–270. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE, Jr, Parham TA, Helms JE. The stages of Black identity development: Nigrescence models. In: Jones RL, editor. Black psychology. 3. Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry Publishers; 1998. pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Templeton J, Barber B, Stone M. Adolescence and emerging adulthood: The critical passageways to adulthood. In: Bornstein MH, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, Moore K, editors. Well-being: Positive development across the life course. Mahweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity Youth and Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. Racial/ethnic identity, congruence with the social context, and transition to high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;15:587–602. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliones J. The Pittsburgh Project--Part II: Construction of a Black consciousness measure. Paper presented at the Third conference on empirical research in Black Psychology; Cornell University; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Milliones J. Construction of a Black consciousness measure: Psychotherapeutic implications. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. 1980;17:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Munford MB. Relationship of gender, self-esteem, social class, and racial identity to depression in Blacks. Journal of Black Psychology. 1994;20:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CS. African-American adolescent women: Perceptions of gender, race, and class. Marriage and Family Review. 1996;24:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Parham TA, Helms JE. The influence of Black students’ racial identity attitudes on preferences for counselor’s race. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1981;28:250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(3):499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer DL. Patterns of racial identity development of African American adolescent males and females. Journal of Black Psychology. 1995;21:168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal RL, Rosnow R. If you’re looking at the cell means, you’re not looking at only the interaction (unless all main effects are zero) Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:574–576. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ. Profiles of African American college students’ educational utility and performance: A cluster analysis. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Chavous TM, Cooke DY. A person-centered approach to African-American gender differences in racial ideology. Self and Identity. 2003;2:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith MA. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E, Scottham K, Sellers R. The status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories, and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Cooke DY. Racial ideology and racial centrality as predictors of African American college students’ academic performance. Journal of Black Psychology. 1998;24:8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Copeland-Linder N, Martin P, Lewis R. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton NJ. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. The Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Sellers RM. Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius JM, Veniegas RC. Gender and race discrimination: The interactive nature of disadvantage. In: Oskamp S, editor. Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker S. Identity theory: Developments and extensions. In: Honess T, Yardley K, editors. Self and identity: Psychosocial perspectives. London: John Wiley; 1987. pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. Assimilation Blues: Black Families in a White Community. New York, NY: Greenwood Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. ‘Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?’. New York, NY, US: Basic Books, Inc; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American ethnic identity across the lifespan: A cluster analysis of identity status, identity content and depression among adolescents, emerging adults and adults. Child Development. 2006;77:1504–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]