Abstract

This study tested the longitudinal association between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity among a sample of 219 African American adolescents, aged 14 to 18. Structural equation modeling was used to test relations between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity dimensions, namely racial centrality, private regard, and public regard at three time points. The results indicated that perceived racial discrimination at Time 1 was negatively linked to public regard at Time 2. Nested analyses using age were conducted and perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 2 were negatively linked to private regard at Time 3 among older adolescents. The findings imply that perceived racial discrimination is linked to negative views that the broader society has of African Americans.

Keywords: Racial Discrimination, Racial Identity, African Americans/Blacks, Adolescents, Longitudinal

Adolescence is the developmental period when identity is negotiated and solidified for all adolescents (Erikson, 1968). In addition to the normative identity exploration that all youth undergo, youth of color also crystallize and formulate an identity related to their racial and ethnic group membership (Phinney, 1989). An added complexity to the normative process of identity development is the fact that minority youth contend with perceived racial discrimination, which may negatively influence developmental paths. Theoretical work suggests that it is important to consider discrimination as a prominent environmental characteristic for minority youth which may place them at risk for negative outcomes (Swanson et al., 2003). Yet, few empirical studies have examined the relation between racial identity and perceptions of racial discrimination among African Americans during this unique developmental period.

The Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST) model incorporates ecological systems with identity development in describing normative processes for minority youth (Spencer, Fegley & Harpalani, 2003). Specifically, PVEST argues that racial discrimination is a risk factor, which increases the net vulnerability for youth of color, and may result in adverse consequences if youth do not develop appropriate coping strategies and support skills (Spencer, 2006). Identity development is considered to be central and foundational in this framework, which provides the foundation for future behavior, which is either productive or adverse, throughout the life span (Spencer, 2006). PVEST also argues that emergent identities arise out of coping with stressors like racial discrimination as minority youth appraise their role in specific situations (Spencer, 2005). Despite the assumption that negative identities are assumed to be a reaction to coping with stressors such as racial discrimination (Spencer, 2006), the identities that minority youth develop has implications for developmental outcomes (Spencer et al., 2006). Therefore, it is important to know whether African American youth develop healthy identities in the context of a chronic and pervasive stressor such as racial discrimination (Swanson et al., 2003). Given the importance ascribed to healthy identity development for adolescence and young adulthood (Erikson, 1968), it is important to know whether perceived racial discrimination is an antecedent of racial identity. It is also necessary to empirically examine existing theoretical frameworks that have articulated the relation between perceived racial discrimination and racial identity among African American youth. Though prior theoretical formulations are not inherently developmental, studying them during the developmental period when identity is solidified (Phinney, 1989) will enhance our understanding of the process whereby perceived racial discrimination and racial identity influence each other. In the present study, the longitudinal relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity among a sample of African American youth was examined. Specifically, the present study explored whether perceptions of differential treatment targeted toward their racial group (racial discrimination) predicts views about their racial group (racial identity), whether racial identity predicts perceptions of racially discriminatory incidents, or whether there is a reciprocal association.

Theoretical Formulations and Empirical Research

Several theoretical perspectives articulate the relation between racial identity and perceptions of racial discrimination. Racial discrimination is defined as dominant group members’ actions that have a differential and negative effect on subordinate racial/ethnic groups (Williams, Neighbors & Jackson, 2003). A common link among several perspectives is the notion that racial discrimination subsequently influences the development of racial identity among minority group members. The Nigresence model posits that an encounter with racism or racial discrimination may trigger the exploration of racial identity (Cross, 1991). Specifically, it was suggested that this experience may serve as a stimulus for progression from an unaware racial identity to one that understands the role that race plays in the lives of African Americans (Cross, 1991). Social Identity Theory suggests that a social identity is defined as the person’s awareness that he/she belongs to specific social groups, and that this knowledge has emotional value and significance (Tajfel, 1979). Yet, one’s in-group may be negatively perceived by the larger society and recognition of dominant group (racial) discrimination against one’s social group increases group identification in an effort to maintain a positive self-image (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). The Rejection-identification Model posits that the willingness to make attributions to prejudice increases group identification (Branscombe, Schmitt & Harvey, 1999). Consequently, the pervasiveness of racial discrimination results in the notion that majority group acceptance is improbable, thus minority group members are motivated to seek acceptance from their group to satisfy their need for belonging (Branscombe et al., 1999). Specifically, the model suggests that racially discriminatory incidents positively increase identification with one’s racial/ethnic group.

Previous research examining theoretical paradigms that perceptions of racial discrimination influence racial identity has been mixed. Using the Nigresence framework, Hall and Carter (2006) found that higher levels of Immersion-Emersion attitudes were related to perceptions of racial discrimination over the lifetime among a sample of Afro-Caribbeans, as opposed to perceived racial discrimination being linked to racial identity. Prior research using Social Identity Theory indicated that perceptions of discrimination were linked to the development of a pan ethnic identity and consciousness (Masuoka, 2006). Specifically, the results indicated that perceived discrimination strengthened pan ethnic identity among national samples of Asian Americans and Latinos. Yet, Romero and Roberts (1998) examined the tenets of Social Identity Theory using a sample of African American, European American, Mexican American and Vietnamese American adolescents. They indicated that racial identity (exploration levels) predicted perceived discrimination as opposed to discrimination predicting exploration (Romero & Roberts, 1998). Also, perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination were unrelated to racial/ethnic identity among Armenian, Mexican American and Vietnamese youth (Phinney, Madden & Santos, 1998) and unrelated to negative personal evaluations among African American adolescents (Wong, Eccles & Sameroff, 2003). Romero and Roberts (2003) tested the Rejection-identification model among a cross sectional sample of Mexican American youth. The results indicated that increased perceptions of racial discrimination were associated with less ethnic affirmation and exploration among Mexican American adolescents (Romero & Roberts, 2003). Lee, Noh, Yoo and Doh (2007) reported that perceived discrimination was negatively related to ethnic identity among a sample of Koreans living in China. In another test of the Rejection-identification model, Pahl and Way (2006) employed a longitudinal sample of African American and Latino adolescents and found that perceptions of discriminatory acts by peers were associated with increased ethnic identity exploration over time. Branscombe and colleagues (1999) also reported that perceptions of racial discrimination increased identification with one’s own minority group among African American college students and adults.

Theoretical formulations have also proposed that racial identity is a person characteristic that influences perceptions of racial discrimination, such that individuals for whom race is important perceive more racially discrimination incidents than individuals for whom race is less important (Sellers, Morgan & Brown, 2001). Previous empirical research has generally been consistent with this hypothesis in that African American adolescents and young adults who considered race important perceived more racially discriminatory incidents than those who did not (Scott, 2004; Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone & Zimmerman, 2003). Additionally, prior work among African American, Latino American and European American college students indicated that those more strongly identified with their racial/ethnic group reported more incidents of racial discrimination (Operario & Fiske, 2001; Major, Gramzow, McCoy, Levin, Schmader & Sidanius, 2002). Longitudinal research is also consistent such that African American college students who considered race to be a central component of their identity subsequently perceived more incidents of racial discrimination (Sellers & Shelton, 2003).

Although prior research is consistent with theoretical formulations that racial identity and racial discrimination influence each other, a few limitations are noted. The first limitation concerns the imprecise use of racial identity. With the exception of a few studies (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Pahl & Way, 2006), prior research has not specified which racial identity dimensions are more likely to be linked to perceptions of racial discrimination. The majority of research has utilized one-dimensional measures of racial identity and hypothesized that “more” racial identification will be linked to or affected by perceptions of racial discrimination (Branscombe et al., 1999; Phinney et al., 1998; Wong et al., 2003). The lack of specificity regarding the racial identity dimensions has resulted in confusion regarding the meaning of “more identification” with racial discrimination. For example, Branscombe et al. (1999) indicated a positive relation between racial discrimination and racial identity, but Romero and Roberts (2003) indicated a negative relation between racial discrimination and two specific racial identity dimensions: affirmation and exploration. The second limitation is that the bulk of prior work is cross-sectional thereby preventing a longitudinal assessment of the two constructs. Although previous research suggests that racial identity influences racial discrimination and that racial discrimination influences racial identity (i.e., Romero & Roberts, 2003; Scott, 2004; Major et al., 2002), the cross-sectional designs prevent elimination of the alternative explanation for each study. Consistent with prior work (Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Pahl & Way, 2006), longitudinal studies are necessary in order to disentangle the specific relation between racial identity and racial discrimination. Lastly, previous research has not considered the relation between racial identity and perceived racial discrimination in a developmental context. Age may be likely to influence the relation between racial identity and perceived racial discrimination because prior work indicates that age was related to both constructs. Theoretical formulations suggest that racial identity changes will be evident as youth mature through the adolescent period (Phinney, 1989). Empirical work is consistent in that exploration levels peaked in middle adolescence (15–16) and subsequently decreased among African American and Latino youth over a period of four years (Pahl & Way, 2006). Additionally, previous research indicates that older adolescents (14–17) or adolescents in higher grades (12th grade) perceived more racial/ethnic discrimination than their younger counterparts among samples of African American, Hispanic, Asian American and European American adolescents (Romero & Roberts, 1998; Fisher, Wallace & Fenton, 2000). Consequently, age might influence the relation between racial identity and perceived racial discrimination among African American youth.

The Current Study

The Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI) was utilized in order to assess the relation between racial identity dimensions and perceived racial discrimination. The MMRI articulates individual differences in the meaning and significance that African Americans ascribe to racial identity content (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998). The MMRI is comprised of four related dimensions, but only two are examined in the present study: centrality and regard. Racial centrality refers to the extent to which an individual normatively defines her racial group membership or the significance that individuals place on race. The second dimension, racial regard refers to individuals’ affective attitudes towards African Americans, and is divided into two components--public regard and private regard. Private regard refers to the extent to which an individual feels positively or negatively about being a member of the African American community. Public regard refers to the extent to which an individual feels that the broader society views the African American community positively or negatively.

The present study utilizes a three-year longitudinal sample of African American adolescents to examine the relation between two racial identity dimensions (centrality and regard) and perceptions of racial discrimination over time. As such, structural equation modeling (SEM) is the most appropriate analytic tool because it affords the opportunity to examine the cross-lagged relations between racial discrimination and the racial identity dimensions across time, while simultaneously examining model fit for each racial identity dimension. Additionally, analyses will be conducted to examine nested models to assess if the relation between the racial identity dimensions and perceptions of racial discrimination is influenced by age.

The first research question examines the longitudinal relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial centrality. Prior theoretical works suggests that perceptions of racial discrimination should increase the significance attached to group identification (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), and that racial centrality will result in increased perceptions of racial discrimination (Sellers et al., 2001). It is of interest to examine if perceived racial discrimination predicts racial centrality, if racial centrality predicts perceptions of racial discrimination, or if there is a reciprocal relation among African American youth. The second question examines the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and private regard, as prior theoretical work suggests that minority group individuals will internalize negative views resulting from racially discriminatory incidents (Cooley, 1956). Thus, perceptions of racial discrimination should negatively predict private regard levels among African American youth. The third question examines the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and public regard since theoretical formulations argue that the willingness to attribute discrimination to race increases group identification (Branscombe et al., 1999). Consequently, perceptions of racial discrimination should negatively predict public regard levels among African American youth. The last research question examines whether the relation between the racial identity dimensions and racial discrimination is moderated by age. Consistent with prior research (Fisher et al., 2000), age was dichotomized into middle (14–16) and late (17–18) to examine if the relation between perceived racial discrimination and the racial identity dimensions varied across the two age groups.

Method

Participants

These data are drawn from a three-year longitudinal study of racial identity development, racial socialization, and psychological adjustment among African American adolescents residing in the Midwest. At all three time points, data were collected from both an adolescent and his/her primary caregiver. In the first year of the study, the sample included 314 adolescents and the average age of the sample was 13.84 years (SD = 1.11). A year later, at Time 2, the study retained 224 students from Time 1 and the average age of the sample was 14.80 years (SD = 1.11). Another year later, at Time 3, the study retained 219 students from previous times points and the average age of the sample was 15.81 years (SD = 1.12). The retention rate across three years of the study was approximately 70%. Since the objective of this study was to examine changes in the relation between experiences of discrimination and racial identity, only adolescents who completed all three waves were included. Two-hundred and nineteen (N = 219) African American adolescents, 40% male and 60% female, comprised the sample reported here. Age was dichotomized into groups for analyses: middle (14 – 16; n = 87) and late (17 – 18; n = 132). A large majority (70%) of primary caregivers reported having completed some college and median family incomes of $40,000–$49,000. Although the median income for African American families in this community is greater than the national average range ($30,000 – $39,000), there is variation for the participants’ families. Analyses were conducted to assess differences between those who participated at all time periods and those at time one only, and the results indicated no significant differences on demographic or study variables.

Procedure

With assistance from public school administrators, all students of African descent attending a large, mid-western public school district were eligible and recruited for the study. African American families comprise approximately 9% of the community. Students attended 10 schools (six middle and four high schools). Families were contacted via telephone or mail about the study and returned signed consent forms to indicate their interest in participating. At each survey administration, adolescents were also asked to sign assent forms. The questionnaires were administered by African American research assistants and lasted between 45 and 75 minutes. Adolescents completed surveys in small groups after school and received $30, $40, and $50 gift certificates for each year of their participation.

Measures

Racial Identity

To assess racial identity, a version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity adapted for use with Black youth (MIBI-T) was utilized to assess three dimensions of racial identity: centrality, private regard and public regard (see Scottham, Sellers & Nguyen, in press). The MIBI-T was developed based on adolescent focus groups. Confirmatory factor analysis found that the original MIBI model was an adequate fit for the MIBI-T and has been used successfully in research with African American adolescents (see Sellers, Linder, Martin & Lewis, 2006). The scale consists of items with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), such that higher scores on each of the subscales represent strong endorsement of their respective constructs. The racial centrality subscale measures the extent to which race is a defining characteristic for the individual. Three items were used to assess racial centrality (T1: α = .60; T2: α = .53; T3: α = .52), including “I have a strong sense of belonging to other Black people”. The private regard subscale (T1: α = .75; T2:.α = .66; T3: α = .67) has three items and measures the extent to which respondents personally feel about being African American (e.g., “I feel good about Black people”). The public regard subscale (T1: α = .64; T2: α = .66; T3: α = .70) has three items and measures the respondents’ belief of others’ evaluations of African Americans (e.g., “People think that Blacks are as good as people from other races”).

Perceptions of Frequency of Discrimination

The frequency of discriminatory experiences due to being Black was assessed using the daily life experiences (DLE) scale, which is a subscale of the Racism and Life Experiences Scale (RaLes) (Harrell, 1994; 1997). The RaLes assesses racism experienced collectively, individually and vicariously with three types: life event/episodic stress, daily hassles and chronic/contextual stress (Harrell, 1994). The DLE is a self-report measure that assesses daily hassles or the frequency of “microaggressions” because of race in the past year (see Appendix for items). Participants were presented with a list of 18 discriminatory experiences and asked to indicate how often it occurred to them in the past year “because you were Black” (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = a few times, 3 = about once a month, 4 = a few times a month, 5 = once a week or more). Sample items included: “Having your ideas ignored” and “Not being taken seriously”. Previous psychometric analyses indicate that internal consistency was adequate for this subscale, with construct validity indicating that daily life experiences correlated negatively with social desirability and cultural mistrust (Harrell, 1997). Evidence of criterion-related validity was demonstrated in that daily life experiences were related to perceived stress, psychological symptoms and trauma-related symptoms (Harrell, 1997). The mean across the 18 items for the present sample was computed for each of the three time points (T1: α = .93; T2: α = .92; T3: α = .92).

Results

The correlations between variables across three time points are presented in Table 1. Among the Time 1 variables, centrality and private regard were positively associated. Centrality was also positively associated with perceptions of racial discrimination. Among the Time 2 variables, centrality and private regard were positively correlated. Among the Time 3 variables, centrality was positively associated with private regard and perceptions of racial discrimination. Public regard was negatively associated with perceptions of racial discrimination. For adjacent time points, centrality was positively associated between Time 1 and 2, Time 2 and 3, and Time 1 and 3. Similar stability coefficients were observed for private regard, public regard and perceptions of racial discrimination. Centrality at Time 1 was positively associated with private regard at Time 2 and at Time 3 and perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 3. Private regard at Time 1 was positively associated with centrality at Time 2 and 3. Public regard at Time 1 was negatively associated with perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 3. Discrimination at Time 1 was positively associated with Centrality at Time 1 and discrimination at Time 2 and 3 but negatively associated with public regard at Time 2 and 3. Centrality at Time 2 was positively correlated with private regard at Time 2 and 3. Private regard at Time 2 was positively related to centrality at Time 3. Public regard at Time 2 was negatively related to discrimination at Time 3. Discrimination at Time 2 was negatively associated with public regard at Time 3. Centrality at Time 1 was positively associated with discrimination at Time 3.

Table 1.

Zero-order Correlations of the Study Variables

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | RC | PriR | PubR | RD | RC | PriR | PubR | RD | RC | PriR | PubR | RD | ||

| RC | 3.76 | .87 | -- | .39** | .13 | .14* | .56** | .31** | .00 | .09 | .44** | .28** | .12 | .14* | |

| Time | PriR | 4.61 | .59 | -- | .11 | −.02 | .28** | .45** | .00 | −.01 | .22** | .39** | .07 | .06 | |

| 1 | PubR | 3.41 | .72 | -- | −.01 | .05 | .12 | .36** | .00 | .02 | .00 | .30** | −.13* | ||

| RD | 1.69 | 1.13 | -- | .14* | .04 | −.23** | .42** | .11 | −.06 | −.25** | .43** | ||||

| RC | 3.82 | .81 | -- | .44** | −.11 | .08 | .58** | .40** | .06 | .11 | |||||

| Time | PriR | 4.60 | .61 | -- | .08 | −.01 | .36** | .60** | .12 | .02 | |||||

| 2 | PubR | 3.19 | .90 | -- | −.12 | −.09 | .00 | .50** | −.18** | ||||||

| RD | 1.49 | .92 | -- | .11 | −.08 | −.16* | .53** | ||||||||

| RC | 3.83 | .88 | -- | .45** | .02 | .16* | |||||||||

| Time | PriR | 4.59 | .55 | -- | .09 | −.06 | |||||||||

| 3 | PubR | 3.04 | .91 | -- | −.26** | ||||||||||

| RD | 1.54 | .99 | -- | ||||||||||||

Note. RC = Racial Centrality; PriR = Private Regard; PubR = Public Regard; RD = Racial Discrimination

p < .01,

p<. 05,

p<. 01, N = 219

To examine change in centrality, private regard, public regard and racial discrimination over the three time points, repeated measures analyses were conducted. Results suggested that there were no changes in centrality or private regard over time, however public regard seemed to decrease linearly over time, F (1, 218) = 17.35, p < .01. In addition, racial discrimination seemed to change over time such that reports decreased at Time 2 but increased again at Time 3, F (1, 218) = 4.22, p < .05. Age effects on each of the four variables were examined and the results were not significant.

In order to examine the longitudinal association between experiences of racial discrimination and racial identity, structural equation modeling techniques were employed. To control for previous level of racial discrimination and racial identity, stability coefficients were estimated. To model the associations between identity and racial discrimination, both synchronous (i.e., within time) and cross-lag (i.e., across time between adjacent time points) were estimated. Each of the three racial identity subscales was tested in separate models.

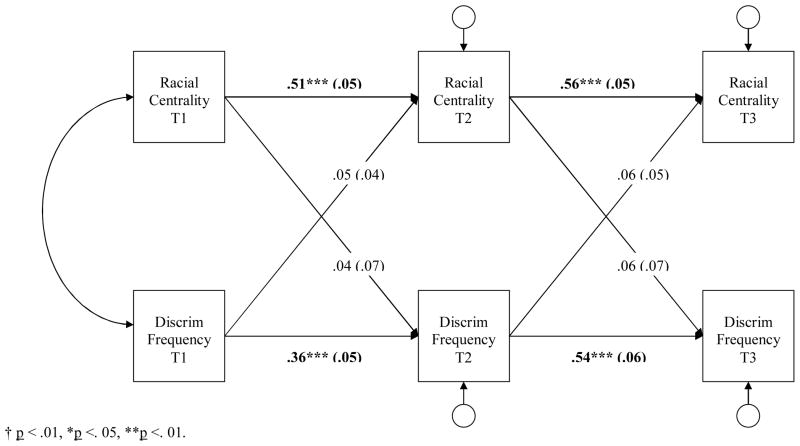

Examining racial centrality and racial discrimination over time, the stability coefficients were significant (Figure 1) such that adolescents with higher centrality at Time 1 were more likely to report high centrality at Time 2. Similar patterns were observed between Times 2 and 3. As with centrality, racial discrimination was positively associated between Times 1 and 2, and Times 2 and 3. The fit for this model was good according to various fit indices (χ2 = 23.92, df = 6, χ2/df = 3.99, TLI = .85, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .12). There were no cross-lag effects observed between racial discrimination and racial centrality.

Figure 1.

Model testing longitudinal associations between racial centrality and discrimination frequency.

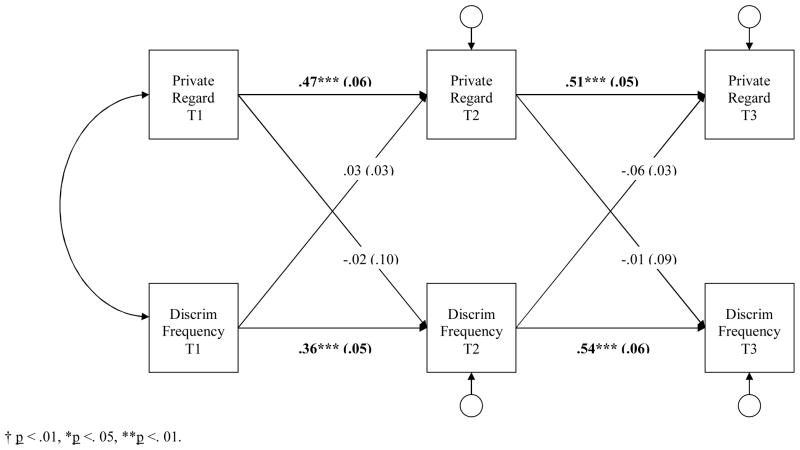

Similar to racial centrality, the association between private regard and racial discrimination over time reveals significant stability for private regard and racial discrimination (Figure 2). Adolescents with higher private regard levels at Time 1 were also more likely to report high private regard at Time 2. Similar patterns were observed between Times 2 and 3. Racial discrimination was also stable between Times 1 and Times 2, and Times 2 and Times 3. The fit for this model was good according to various fit indices (χ2 = 26.33, df = 6, χ2/df = 4.39, TLI = .81, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .13). Again, no cross-lag effects were observed.

Figure 2.

Model testing longitudinal associations between private regard and discrimination frequency.

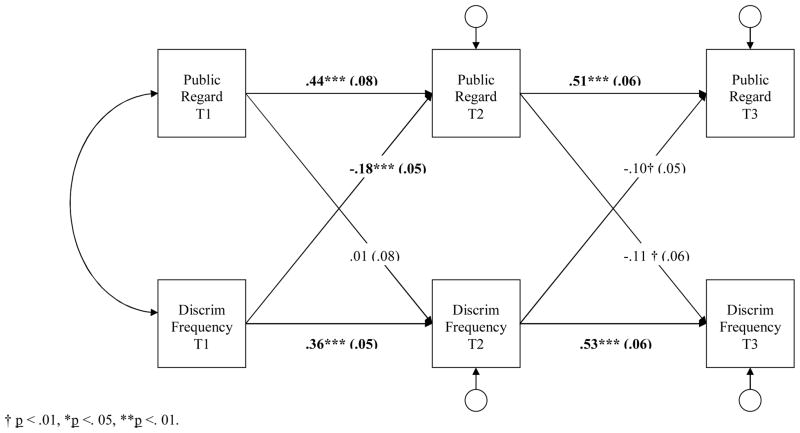

Public regard and racial discrimination were stable over time such that higher reports were positively associated across time (Figure 3). In addition to stability, perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 1 were negatively associated with public regard at Time 2 such that more frequent experiences of racial discrimination at Time 1 was associated with lower public regard at Time 2 (belief that others views Blacks more negatively). The same pattern was observed between Time 2 and Time 3; however this path was not statistically significant. The fit for this model was good according to various fit indices (χ2 = 30.34, df = 6, χ2/df = 5.06, TLI = .75, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .14).

Figure 3.

Model testing longitudinal associations between public regard and discrimination frequency.

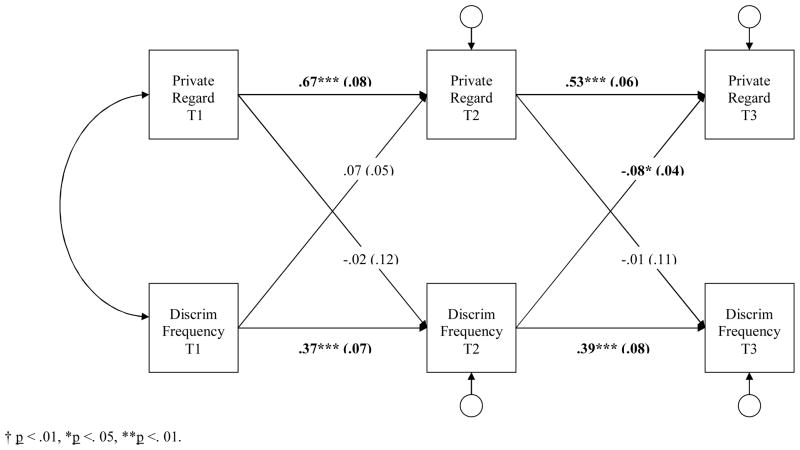

To test for age effects, each of the three models was compared for middle and older adolescents. Nested modeling analyses was conducted which entails constraining the regression coefficients equal for the two groups, and then comparing the results for the nested design to the overall model with no constraints to determine significance. The unconstrained model assumes that the regression coefficients for the two groups do not vary, while the constrained model assumes that the two groups vary. If the constrained model improves the model fit for the unconstrained model, evidence is provided that the relations among the variables are not equivalent for the two groups. The change in X2 for the constrained and unconstrained models is compared to the critical ratio for significance. The critical ratio for a X2 test with eight degrees of freedom is 15.51. The results for racial centrality (ΔX2 = 9.26, Δdf = 8, p >.05) were non-significant suggesting that the relation between racial discrimination and racial centrality did not vary for middle aged and older youth. The results for private regard (ΔX2 = 16.21, Δdf = 8, p <.05) were significant. Specifically, the results suggest that among late adolescents, reports of more frequent racial discrimination at Time 2 was associated with lower private regard at Time 3 (Figure 4). The results for public regard (ΔX2 = 5.61, Δdf = 8, p >.05) were also non-significant suggesting that age did not moderate the relation between racial discrimination and public regard.

Figure 4.

Model testing longitudinal associations between private regard and discrimination frequency among late adolescents.

Discussion

The results of the present study do not support a relation between perceptions of racial discrimination, racial centrality, and private regard among African American adolescents. These results are contrary to prior theoretical frameworks suggesting that recognition of discrimination increases the significance attached to social groups that have negative perceptions by the larger society (Tajfel, 1979; Branscombe et al., 1999). The results are also contrary to prior theoretical work suggesting that individuals with high levels of racial centrality will perceive more racially discriminatory incidents (Sellers et al., 2001). Two explanations are offered for the non-significant relations between perceived racial discrimination, racial centrality and private regard. Our first explanation is that perceptions of racial discrimination may be linked to racial identity development as opposed to racial identity content, with the exception of public regard. Pahl and Way (2006) indicated that perceptions of discrimination were linked to increasing exploration over a four year period among Black and Latino youth. Exploration is one of the dimensions that comprise identity development (see Marcia, 1966) and racial identity development (see Phinney, 1989). Both conceptualizations propose the existence of four identity statuses (i.e., diffused, foreclosure, moratorium and achievement) based on the presence and absence of exploration and commitment. In light of existing findings, perceptions of discrimination may be linked to racial identity development (i.e., exploration) but not racial identity content (i.e., racial centrality and private regard). This perspective is consistent with the Nigresence model which suggested that racially discriminatory encounters would trigger an exploratory phase resulting in a developed and nuanced racial identity (Cross, 1991). Thus, discrimination may be an impetus for dimensions of racial identity development such as exploration, but not dimensions of racial identity content such as racial centrality and private regard. Future research should consider examining whether perceptions of racial discrimination are more likely to be linked to dimensions of racial identity content or racial identity development.

Our second explanation for this finding concerns the idea that adolescent perceptions of racial discrimination may be unrelated to racial centrality and private regard due to their specific contexts. Schools and neighborhoods are two important contexts for child and adolescent development (Jessor, 1993). African American youth typically live in racially segregated neighborhoods (Willams & Collins, 2004) and attend racially segregated high schools (Logan, 2002). Despite the fact that racial segregation is normative for African American adolescents, youth in the present sample attend racially heterogeneous schools and reside in racially heterogeneous neighborhoods. It is possible that racial centrality and private regard may be influenced by whether African American youth are in majority or minority settings. Thus, youth in the present study are in racially heterogeneous settings, resulting in their ability to separate racially discriminatory incidents from the significance and meaning they ascribe to their racial group membership given that previous research has shown the salience and meaning of ethnic identity for Asian Americans varied depending on whether they were in California or the Midwest (Umana-Taylor & Shin, 2007). Alternatively, youth in more racially segregated settings may be less skilled in separating perceptions of racial discrimination from their racial identity as their environments are more homogeneous. Although previous research has not examined contextual influences on adolescent perceptions of racial discrimination or racial identity, it may be an important variable to consider in future research.

The present results indicate that perceptions of racial discrimination are subsequently linked to public regard. Public regard constitutes an idea about how the broader society views African Americans, positively or negatively. Perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 1 are negatively associated with public regard at Time 2, and a trend was found for public regard at Time 2 to be negatively related with perceptions of discrimination at Time 3. Racially discriminatory incidents reinforce the notion that general society has a negative perception of African Americans, which further increases perceptions of racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Thus, experiences predict views, which seemingly predict experiences. The results are consistent with the PVEST model in that racial discrimination is proposed to be a chronic stressor for African American youth and that emerging identities are formed in the process of coping with this stressor (Spencer, 2006; Spencer et al., 2003). The decreasing public regard levels suggest that over time African American youth recognize that the broader society has a negative view of African Americans, which appears to be reinforced by their perceptions of racially discriminatory experiences. The results support a tenet of the PVEST model, which suggests that it should not be assumed that African American youth form negative identities in the context of racial discrimination (Spencer, 2006). Additionally, the results lend support to the idea of person-context process in that African American youth are constructing their identity regarding the broader society’s view of African Americans in a manner that is consistent with their experiences of racial discrimination. Yet, the results are inconsistent with prior theoretical frameworks, which propose that experiences of racial discrimination should increase group identification (Tajfel, 1979; Branscombe et al., 1999). One reason for the inconsistency is due to the lack of specificity regarding which aspects of racial identity will be linked to perceptions of racial discrimination. The present findings suggest that public regard is the aspect of racial identity that is most likely to be influenced by African American adolescents’ perceptions of racial discrimination. Similarly, it is hoped that the specific relations between racial identity and perceptions of racial discrimination will be understood as more nuanced research is conducted examining the specific dimensions of racial identity.

The findings also indicate that these relations vary according to the age of African American youth in that age moderates the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and private regard. Private regard is the extent to which an individual feels positively or negatively about being African American. Specifically, perceptions of racial discrimination at Time 2 are negatively associated with private regard at time three among youth aged 17 to 18. Racially discriminatory encounters are linked with older youth feeling more negative about being African American. One reason for this finding may be attributed to the interaction between racial identity development and racial identity content. Previous research among African American adolescents, college students, and adults indicates that those in more advanced stages of racial identity development have more positive private regard levels (Yip, Seaton & Sellers, 2006). Specifically, individuals who have explored and committed to a racial identity feel more positive about being African American than those who have not explored or committed (Yip et al., 2006). As observed in previous research (Yip et al., 2006), it is likely that the older youth in this sample may be still in the process of developing an integrated sense of identity and therefore reported relatively lower private regard levels and were therefore less able to cope with perceptions of racial discrimination. Another explanation concerns the increasing perceptions of racial discrimination from Time 2 to Time 3 that is evident across both age groups. This pattern is consistent with prior research that indicates that as minority youth matriculate in high school, their perceptions of racial discrimination increase (Romero & Roberts, 1998; Fisher et al., 2000). As such, perceiving more racial discrimination may result in older youth having less positive private regard in comparison to their younger counterparts. A third explanation is the idea that older youth may be navigating unfamiliar contexts (i.e., employment) increasing the likelihood of racially discriminatory incidents. Previous research indicates that roughly 80% of adolescents will have worked before graduating from high school (Staff, Mortimer & Uggen, 2004). In employment settings, it is possible that African American youth perceive adults to be the perpetrators of racially discriminatory incidents and prior research suggests that Black youth reported an increase in perceived racial discrimination from adults over time (Greene, Way & Pahl, 2006). Consequently, placement in and adjustment to these novel settings with adult perpetrators may hinder older youth’s ability to cope with perceptions of racial discrimination, resulting in less positive private regard levels. Future research should consider the contexts of African American youth, but also the perpetrators as they relate to perceptions of racial discrimination.

There are a few limitations in the present study that need to be considered. The initial limitation concerns the measurement of perceived discrimination, which is believed to be a critical area in discrimination research (Williams et al., 2003). Although the instrument in the present study utilizes an annual time period, smaller time periods and experiential sampling techniques might capture discriminatory experiences more precisely, affording the opportunity to examine the frequency with which African American youth experience discrimination in a broader context. At the same time, research on racial discrimination employing daily diary techniques has found discrimination to be a low frequency event (Yip, Kiang & Fuligni, in press); therefore the measurement of discrimination is a topic that merits further attention. Another limitation includes the low reliability scores for the racial centrality measure. The present reliability scores are less than the recommended values and may have contributed to the lack of significant results between racial centrality and perceived racial discrimination. Given that prior work using the original version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) among African American adolescents demonstrated adequate reliability (Rowley, Sellers, Chavous & Smith, 1998), additional work on the racial centrality subscale is necessary. For example, the racial centrality subscale may require additional items or modification of existing items to improve internal consistency. Another possible issue concerns the method of statistical analysis given that the current study utilized structural equation modeling when an alternative method is latent growth curve modeling. Structural equation modeling is in a family of statistical techniques that are similar to multiple regression but more powerful (Kline, 2004). Structural equation modeling estimates relations using confirmatory modeling, which is appropriate for theory testing (Kline, 2004). Latent growth curve modeling is a specific type of structural equation modeling that examines if a specified change model is valid for some dependent variable, and to assess the effect of covariates on the rate of change for three or more time points (Kline, 2004). Given that latent growth curve modeling affords assessment of the effects of the intercepts and slopes of one variable on another, it was believed that structural equation modeling was more appropriate because of the ability to examine the bidirectional relation between racial discrimination and racial identity. Consequently, future research could examine how the intercept and slope for perceptions of racial discrimination influence public regard among African American adolescents as a result of the current findings. The last limitation is the utilization of a convenience sample, which prevents generalizations from being made to other African American adolescents in urban, suburban or rural areas.

The present study represents an important foundation upon which other research can build. The results contribute to our understanding of the longitudinal relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity among African American adolescents. Specifically, the results suggest that prior theoretical work needs to consider specific racial identity dimensions and age when considering the relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity. The present study indicates that perceptions of racial discrimination are not linked to the significance attributed to race or personal evaluations of what it means to be African Americans. Yet, experiences of racial discrimination negatively predict adolescent views about how the broader society views African Americans. Additionally, the results indicate that age makes the relation between racial discrimination and racial identity more complex among African American youth. Specifically, experiences of racial discrimination influence personal beliefs of group membership among older but not young African American adolescents. The present study reiterates the need to disentangle the complex relation between perceptions of racial discrimination and racial identity among African American youth.

Appendix Racism and Life Experiences Scale

Daily Life Experiences (DLE) Subscale

Being ignored, overlooked or not given service (in a restaurant, store, etc.)

Being treated rudely or disrespectfully

Being accused of something or treated suspiciously

Others reacting to you as if they were afraid or intimidated

Being observed or followed while in public places

Being treated as if you were “stupid”, being “talked down to”

Having your ideas ignored

Overhearing or being told an offensive joke

Being insulted, called a name or harassed

Others expecting your work to be inferior (not as good as others)

Not being taken seriously

Being left out of conversations or activities

Being treated in an “overly” friendly or superficial way

Other people avoiding you

Being stared at by strangers

Being laughed at, made fun of, or taunted

Being mistaken for someone else of your same race

Being disciplined unfairly because of your race

Contributor Information

Eleanor K. Seaton, Department of Psychology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Tiffany Yip, Department of Psychology, Fordham University.

Robert M. Sellers, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan

References

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135 – 149. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and the social order. New York: Free Press; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. Shades of black: Diversity in African American identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity, youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679 – 695. [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Schekeva P, Carter RT. The relationship between racial identity, ethnic identity and perceptions of racial discrimination in an Afro-Caribbean descent sample. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. The racism and life experience scales. 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. Development and validation of scales to measure racism-related stress. Poster presented at the 6th biennial conference of the Society for Community Research and Action; Columbia, SC. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Successful adolescent development among youth in high-risk settings. American Psychologist. 1993;48:117–126. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Noh CY, Yoo HC, Doh HS. The psychology of diaspora experiences: Intergroup contact, perceived discrimination and the ethnic identity of Koreans in China. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:115–124. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR. Choosing segregation: Racial imbalance in American public schools, 1990–2000. Albany, NY: Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Gramzow RH, McCoy SK, Levin S, Schmader T, Sidanius T. Perceiving personal discrimination: The role of group status and legitimizing ideology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:269 – 282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1966;3:551 –558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka N. Together they become one: Examining the predictors of pan ethnic group consciousness among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science Quarterly. 2006;87:993–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Fiske ST. Ethnic identity moderates perceptions of prejudice: Judgments of personal versus group discrimination and subtle versus blatant bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;9:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, Santos LJ. Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:937–953. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21:641 – 656. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:2288–2305. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, Smith MA. The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:715–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD. Correlates of coping with perceived discriminatory experiences among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottham KM, Sellers RM, Nguyen HX. A measure of racial identity in African American adolescents: The development of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity Teen. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:297–306. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Linder NC, Martin PM, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187 – 216. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone K, Zimmerman MA. The role of racial identity and racial discrimination in the mental health of African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Morgan LM, Brown TN. A multidimensional approach to racial identity: Implications for African American children. In: Neal-Barnett AM, Contreras JM, Kerns KA, editors. Forging links: African American children clinical developmental perspectives. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2001. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith M, Shelton JN, Rowley SJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Crafting identities and assessing opportunities Post-Brown. American Psychologist. 2005;60:821–830. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups (Chapter 15) In: Damon W, Lerner R, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Theoretical models of human development. 6. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 829–893. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Fegley SG, Harplani V. A theoretical and empirical examination of identity as coping: Linking coping resources to the self processes of African American youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2003;7:181 – 188. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Mortimer J, Uggen C. Work and leisure in adolescence. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson DP, Spencer MB, Harpalani V, Dupree D, Noll E, Ginzburg S, Seaton G. Psychosocial development in racially and ethnically diverse youth: Conceptual and methodological challenges in the 21st century. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:711–743. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Individuals and groups in social psychology. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1979;18:183 – 190. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Austin W, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Shin N. An examination of ethnic identity and self-esteem with diverse populations: Exploring variation by ethnicity and geography. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:178–186. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. Reparations: A viable strategy to address the enigma of African American Health. American Behavioral Scientist. 2004;47:977 – 1000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Kiang L, Fuligni AJ. Multiple social identities and reactivity to daily stress among ethnically diverse young adults. Journal of Research in Personality in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity context and depressive symptoms. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1503–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]