Abstract

This study examined adolescents' emotional reactivity to parents' marital conflict as a mediator of the association between triangulation and adolescents' internalizing problems in a sample of 416 two-parent families. Four waves of annual, multiple-informant data were analyzed (youth aged 11 – 15). Using structural equation modeling, triangulation was associated with increases in adolescents' internalizing problems, controlling for marital hostility and adolescent externalizing problems. There also was an indirect pathway from triangulation to internalizing problems across time through youths' emotional reactivity. Moderating analyses indicated that the second half of the pathway, the association between emotional reactivity and increased internalizing problems, characterized youth with lower levels of hopefulness and attachment to parents. The findings help detail why triangulation is a risk factor for adolescents' development and which youth will profit most from interventions focused on emotional regulation.

Keywords: adolescence, emotional reactivity, internalizing problems, interparental conflict, marital conflict

Exposure to hostile marital conflict is a risk factor for adolescents' development in two-parent families (Cui, Conger, & Lorenz, 2005). One of the mechanisms by which marital conflict becomes a risk factor is the triangulation of the child/adolescent into parental disputes such that youth feel “caught in the middle” and torn between divided loyalties (Amato & Afifi, 2006; Grych, Raynor, & Fosco, 2004). Triangulation is a system process in which a child becomes involved in parents' conflictual interactions by taking sides, distracting parents, and carrying messages in order to avoid or minimize conflict between parents (Minuchin, 1974). Triangulation into parents' disputes has received much less empirical attention than has verbal and physical interparental aggression, however, some evidence exists that triangulation places youth at risk for adjustment problems, particularly internalizing problems such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, and social withdrawal (Gerard, Buehler, Franck, & Anderson, 2005; Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996; Wang & Crane, 2001).

In the current study, a family process model of triangulation was examined in which we proposed that youths' triangulation into parents' marital disputes is associated with increases in adolescents' internalizing problems, controlling for parents' marital hostility and adolescents' externalizing problems. We also proposed that adolescents' emotional reactivity to parents' conflicts partially mediates this association between triangulation and adolescent internalizing problems, and that this indirect pathway is moderated by several individual and family factors that form the context of family interaction processes.

Background

Triangulation and Adolescent's Internalizing Adjustment Problems

Conceptually, “triangulation occurs when two people in a family bring in a third party to dissolve stress, anxiety or tension that exists between them” (Charles, 2001, p. 281). In the present study, we focused on one particular type of triangulation in families, parent-initiated triangulation of offspring into parents' marital conflict. Indicators of adolescents' triangulation into parents' marital conflict include parents' attempts to form an alliance with the child against the other parent and the child becoming the focus of parents' attention to avoid addressing their own problems (i.e., scapegoating or detouring) (Bell, Bell, & Nakota, 2001; Grych et al., 2004).

The hypothesis that triangulation is associated positively with adolescents' internalizing adjustment problems was deduced from Bowenian family systems theory (Bowen, 1978; Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Bowen proposed that parents' anxiety and difficulties with balancing intimacy and autonomy needs (i.e., poor self-differentiation) create marital tension and conflict. He suggested that a primary mechanism for addressing this marital tension is to include a child in the strife so as to reduce/displace personal anxiety and relational tension. This triangulation process represents a boundary violation because it places youth in confusing and distress-provoking situations as they negotiate between parents and manage conflicting loyalties (Amato & Afifi, 2006; Jacobvitz, Hazen, Curran, & Hitchens, 2004). Over time, adolescents' involvement in their parents' relational difficulties places them at risk for psychological distress, particularly problems such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, and withdrawal tendencies (Bradford et al., 2004; Miller, Anderson, & Keala, 2004).

Although research is scant, existing evidence has suggested that triangulation into parents' marital conflict is associated with poorer adolescent functioning (Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbush, 1991; Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996; Wang & Crane, 2001). For example, Grych and his colleagues (2004) found that triangulation completely mediated the concurrent association between marital conflict and adolescent internalizing problems. Amato and Afifi (2006) also found that feeling caught between married parents was associated with lower levels of young adults' subjective well-being (average age 27 years old). Bradford and colleagues (2004) examined the association between youth-reported triangulation into marital conflict and adolescents' depressive symptoms in 11 samples from nine countries and found significant effects in 8 samples. Each of these three studies measured triangulation using youth reports of parental behavior and of feeling caught between parents. Gerard et al. (2005) extended research in this area by demonstrating that parents' self-reports of triangulating behavior also were associated concurrently with adolescent problem behavior, thus providing evidence that the association between triangulation and adolescent problem behavior is not an artifact of single-informant method bias.

Although the reviewed studies have provided support for the theoretical proposition that triangulation is associated positively with adolescents' internalizing problems, each was based on cross-sectional data. Our study builds on this developing empirical literature in four important ways that enhance its contribution to the understanding of family risk and adolescents' mental health. First, the family process model of triangulation and adolescents' internalizing problems examined in this study includes control for marital hostility and adolescents' externalizing problems. This allowed for the consideration of the unique effects of triangulation and marital hostility on adolescents' maladjustment which contributes to a richer explication of the risk factors associated with various aspects of marital conflict. The additional inclusion of adolescent externalizing problems, although not central to the proposed theoretical model, facilitated the examination of specialized effects of triangulation with adolescent internalizing problems, controlling for comorbidity with another important marker of adjustment difficulties. Second, longitudinal, autoregressive patterns were examined by focusing on changes in adolescents' internalizing problems across the first half of adolescence. Third, different reporters provided information on triangulation and adolescent internalizing problems to help minimize shared method bias. Finally, a generative process mechanism, youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict, was examined as a potential explanation of how triangulation is associated with increases in adolescent internalizing problems.

Adolescents' Emotional Reactivity to Marital Conflict

Bowen (1978) theorized that triangulation places offspring at risk for psychological distress by increasing emotional reactivity. Emotional reactivity to parents' marital conflict is defined conceptually as “chronic elevation of arousal and dysregulation of children's emotions and behavior, fostering adjustment problems” (Davies & Cummings, 1994, p. 390). Indicators include prolonged feelings of distress, sadness, fear, anger, vigilance, and preoccupation with parents' marital relationship (Davies, Forman, Rasi, & Stevens, 2002; Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002).

In addition to being a salient construct in Bowen's conceptualization of dysfunctional family system processes, youths' emotional reactivity to parents' marital conflict has been highlighted in Davies and Cummings' Emotional Security Theory (EST; 2006) and in Grych and Fincham's (1990) Cognitive-Contextual Framework of children's responses to marital conflict. EST proposes that repeated exposure to marital hostility is associated with increases in children's and adolescents' emotional reactivity (Davies & Cummings, 2006). EST also posits that prolonged emotional reactivity is associated over time with increases in internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms and anxiety. The cognitive-contextual perspective proposes that emotional reactivity is part of the primary appraisal process when children and adolescents perceive that marital conflict is self-relevant, negative, and potentially threatening (Grych & Fincham; Grych, Harold, & Miles, 2003). Although the current study was not a comprehensive test of either EST or the cognitive-contextual framework, each theoretical perspective supports Bowen's theoretical contention that offspring's emotional reactivity is a potentially important generative mechanism for offsprings' experience with and processing of triangulation into parents' marital disputes.

There is a growing body of research that has documented a longitudinal association between emotional security (Cummings, Schermerhorn, Davies, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2006) and reactivity (Buehler, Lange, & Franck, 2007) and adolescent internalizing problems. Both of these studies included marital distress as the primary predictor and youths' emotional responses to marital conflict as mediators. The present study builds on these findings by focusing on triangulation rather than marital hostility. This shift in focus responds to Fincham's (1994) call for research that moves beyond the effects of marital hostility by addressing other potentially important aspects of marital conflict. As we have shown in this review, both theory and recent research have suggested that youths' triangulation in parental conflicts is a potentially deleterious aspect of marital hostility and is in need of careful examination.

Contextualizing the Generative Process Pathway

EST proposes that various individual and family characteristics moderate the association between (a) destructive marital conflict variables and youths' emotional security in the interparental relationship (Davies et al., 2002; Davies et al., 2006; Davies & Cummings, 2006), and (b) between youths' emotional security and adolescent internalizing problems (Davies et al., 2002). The general proposition of moderating effects, however, has not been examined with regards to the consequences of triangulation and with a specific focus on emotional reactivity rather than the broader construct of emotional security. The examination of moderating effects is an important contribution of the current study, therefore, because a more detailed understanding of the conditions under which the generative mechanism of emotional reactivity operates and does not operate is needed to inform prevention and intervention programs.

Risk and resiliency theories and research provided guidance regarding potential moderators. Protective effects were defined as individual attributes and cohesive family relationships that reduce the deleterious effects of negative relational risk processes on young adults' psychosocial maladjustment (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten & Garmezy, 1985). Three protective moderators were examined: youths' hopefulness (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000) and youths' attachment to mothers and fathers (Waters & Cummings, 2000). We hypothesized that the individual attribute of perceived hopefulness during adolescence partially buffers the deleterious consequences of triangulation on adolescents' internalizing problems. We conceptualized hopefulness as the tendency to report a sense of general well-being, a sense of comfort, and optimism over time and relationships. The hypothesized buffering effects of hopefulness are consistent with research on the positive effects of optimism (Geers, Handley, & McLarney, 2003; Meadows, Kaslow, Thompson, & Jurkovic, 2005). Although we were unable to find research on the moderating effects of hopefulness (or optimism) on the effects of marital conflict on youths' adjustment, we propose buffering effects based on the theoretical proposition that select aspects of offsprings' individual disposition conditionalize marital conflict responses (Grych & Fincham, 1990).

We also hypothesized that higher levels of attachment to mothers and fathers buffer the deleterious consequences of triangulation into parents' disputes. Although this has not been examined in past research, tangential analyses have shown direct associations between attachment security and lower levels of internalizing problems (Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998), and significant buffering effects for maternal attachment security with regards to the deleterious effects of marital hostility (Davies et al., 2002).

Amplification moderators are additional individual, relational, or contextual factors that exacerbate the negative effects of a focal risk factor (Gore & Eckenrode, 1996). Three amplification moderators were examined: youth gender (Davies & Lindsey, 2004) and mothers' and fathers' depressive symptoms (Hops, Sherman, & Biglan, 1990). Although gender moderating analyses in marital conflict research have resulted in null or inconsistent findings (Cox, Paley, & Harter, 2001; Gerard, Krishnakumar, & Buehler, 2006), Davies and Lindsey (2004) found stronger negative consequences of marital conflict for daughters than for sons and this finding was explained by female youths' greater communion orientations. This gender-related finding is salient for the present study when combined with research that has documented girls' higher levels of internalizing problems during early adolescence that have corresponded with greater rumination tendencies (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus,1994).

Although more is known about the effects of mothers' than fathers' depressive symptoms, parents' depressive symptoms also might increase adolescents' vulnerability to the negative effects of relational risk processes (Downey & Coyne, 1990). For example, offspring exposed to both marital hostility and parents' depressive symptoms are at greater risk for problem behaviors than are offspring exposed to only one of these risk factors (Essex, Klein, Cho, & Kraemer, 2003). Although we were unable to find research that has documented interaction effects between parental depression and triangulation, we speculated that parental dysphoria creates an environmental context for offspring that is conducive to internalized distress response to salient family stressors. Thus, we hypothesized that adolescents exposed to higher levels of parents' depressive symptoms would be more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of triangulation and emotional reactivity, particularly with regards to predicting increases in adolescents' internalizing problems.

In summary, four hypotheses were tested in this study. First, we hypothesized that adolescents' triangulation in parents' marital conflict is associated positively with increases in adolescents' internalizing problems, controlling for marital hostility and adolescents' externalizing problems. Second, we hypothesized that youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict partially mediates the associations between triangulation and adolescents' increases in internalizing problems. Third, we hypothesized that youth hopefulness and attachment to mothers and fathers buffer the pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems. Fourth, we hypothesized that parents' depressive symptoms and being a female youth amplify the pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems.

Method

Sampling Procedures and Characteristics

The sample was taken from a larger study of the effects of family life on the transition from childhood into adolescence. For the larger study, 6th grade youth in 13 middle schools in a large, geographically diverse county in the southeastern United States were invited to participate. Children in 6th grade were selected because they are beginning the transition from childhood into adolescence. Ninety-six percent of the teachers participated. Youth received a letter during homeroom inviting their participation. Two additional invitations were mailed directly to parents. Consent forms were returned by 71% of the youth/parent(s) and 80% of these youth received parental permission to complete a questionnaire on family life during school. This resulted in a sample of 2,346 6th grade youth. The sample was representative of families in the county on race, parents' marital status, and family poverty status (contact the author for details using county census information).

Families for the present study of two-parent families were recruited from the larger sample of youth using the following criteria: parents were married or long-term cohabitants and no stepchildren were in or out of the home. Married or long-term cohabitants were examined because the effects of triangulation on adolescent well-being have been particularly strong in married rather than divorced families (Amato & Afifi, 2006). Stepfamilies were not included for three reasons: (a) stepfamilies have complex structures that differ from ever-married families and a careful study would need to include adequate sample sizes of these various structures to conduct group comparisons; (b) data would need to be collected regarding birth parent-child relations as well as stepparent-child relations in order to understand the findings accurately; and (c) funds were inadequate to collect questionnaire and observational data from both stepparents and nonresidential birth parents.

Of the 1131 eligible families from the larger study, 416 (37%) agreed to participate. Primary reasons given for nonparticipation included time constraints and/or an unwillingness for one or more family members to be videotaped. This response rate was similar to that in studies that have included 3 or 4 family members and have used intensive data collection protocols (e.g., NSFH-34%; Updegraff et al., 2004-37%). Using information from the initial youth survey for selection analyses, eligible participating families were similar to eligible nonparticipating families on all study variables, suggesting minimal selection bias. (Contact corresponding author for statistical details from the multivariate and univariate analyses of variance.)

At wave 1 when youth were in the 6th grade (W1), they ranged in age from 11 to 14 (M = 11.86, SD = .69). There were 211 daughters (51%). In terms of race, 91% of the families were European American and 3% were African American. This 3% is lower than the percentage of married African American couples with their own children younger than 18 in the county (5%) and in the United States (7.8%) (U.S. Census, 2000, Table PCT27 of SF4). The average level of parents' education in this sample was an associate's degree (2 years of college). Parents' educational attainment was similar to that of European American adults in the county who were older than 24 (county mean category was some college, no degree; U.S. Census, 2000, Table P148A of SF4). The median level of 2001 household income for families in this study was about $70,000, which was higher than the median 1999 income for married-couple families in the county ($59,548, U.S. Census, 2000, Table PCT40 of SF3).

To further demonstrate the utility of this sample for the present study, the distributions of marital hostility and adolescents' internalizing problems at W1 (6th grade) were compared to norms and national distributions. The prevalence of physical marital aggression in the present sample (6.7%) was comparable to rates found in the 1985 National Survey of Family Violence (NSFV; 3.4%) and 1994 National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH; 6.4%) (Straus & Gelles, 1986; Sweet & Bumpass, 2005). The amount of verbal aggression in the sample (78.4%) was comparable to that found in the 1985 NFVS (75%). Using the Child Behavior Checklist-YSR (Achenbach, 1991c), the percentage of youth in the present sample who scored in the clinical range on self-reported internalizing problems was 15% (M raw score = 10.96, SD = 7.62) which was comparable to that reported by Achenbach (M raw score = 11.70, SD = 7.8).

Data Collection Procedures

Youth completed a questionnaire during school. They had as much time as needed to finish, and several trained assistants and the study director were available to answer questions. After completion, students were treated to a pizza party. Family members (i.e., mothers, fathers, youth) also were mailed a questionnaire and asked to complete it independently. The completed questionnaires were collected during a home visit. Parents and youth completed another brief questionnaire during the home visit. This second questionnaire contained the most sensitive information (e.g., marital hostility) and a researcher's presence ensured privacy.

Family members also participated in three interaction tasks during the home visit. The first two tasks focused on parent-child relationships. Youth interacted separately with mother and father in a 15-minute semi-structured discussion of parent-child relationships. The order for the mother-child and father-child task was randomized by using a coin flip. Topics for discussion, using discussion cards that family members alternated reading, included shared activities, areas of conflict, parental expectations, and consequences of child's misbehavior. The third task was a problem-solving discussion activity. This task involved the mother, father, and youth and focused on trying to solve issues of contention selected by family members. At the beginning of the home visit, each family independently completed the 28-item Issues Checklist (Conger et al., 1992). Item 28 on this checklist was an “other” option in which family members had the chance to list and rate issues not identified on the checklist. The home visitors selected eight areas of disagreements from family members' reports, beginning first with issues identified by all three of the family members. During the 20-minute discussion task, family members were asked to elaborate a given issue, identify who usually is involved, and to suggest possible solutions. Participants were told they did not need to get through all of the issues, and were not stopped if they digressed onto self-selected discussion topics (home visitors were out of sight and ear shot during each task to ensure family privacy).

The semi-structured interaction was videotaped. Trained coders (over 250 training hours) rated the interaction using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). Coders passed an extensive written exam (90% correct criterion) and a viewing exam (criterion level 80% match with ratings by experienced Iowa State University coders). Each family member's behavior was coded during each task. Within each family, different trained coders rated the interaction from the tasks to minimize coder carryover effects.

As part of the longitudinal research design, assessments (questionnaires and observations) were conducted again a year later (W2), two years later (W3), and three years later (W4). Most youth were in 7th grade at W2 (Mean age = 12.84, SD = .68), in 8th grade at W3 (Mean age = 13.83, SD = .67), and in 9th grade at W4 (Mean age = 14.84, SD = .68). Data collection procedures were similar for each wave. Family members were mailed a questionnaire and asked to complete it independently. The completed questionnaires were collected during a home visit. Parents and youth completed another questionnaire during the home visit. There were 366 participating families at W2, 340 families at W3, and 320 at W4 (77% retention of W1 families). Attrition analyses using MANOVA were conducted using the W1 data and there were no differences between the retained and attrited families on any of the study variables. For example, we grouped variables into sets based on content and reporter, and analyzed the data using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Five MANOVAs were estimated that included variables for the present study, and none of the multivariate Fs were statistically significant (.64 - 1.60). Thus, there was little evidence of attrition bias. Families were paid $100 for their participation in W1, $120 for W2, $135 for W3, and $150 for W4.

Measurement

Adolescents' triangulation into parents' marital disputes

Triangulation was measured at W1 with self-reports and spouse reports of each others' behavior using a 13-item Triangulation questionnaire scale created using items from four existing measures (Buehler et al., 1998, 4 items; Grych, Seid, & Fincham, 1992, 3 items; Kerig, 1996, 3 items; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001, 3 items) to increase content validity. Items focused on parent-initiated triangulation. The 5-point response format ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Sample items were “How often does your spouse … involve this child in disagreements between you and your spouse,” and “… try to get this child to side with you during family or marital disagreements.” Items were averaged and a higher score indicated greater triangulation. Mothers' self and spouse reports were averaged to create a composite score, as were fathers' self and spouse reports. Cronbach's alphas were above .89 (Table 1). These composite summary scores were created because preliminary analyses of the measurement model indicated that the error residuals for self and spouse reports were highly correlated (above .60).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Central Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. WR W1 triangulation | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. HR W1 triangulation | .37 | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Adol. internalizing W4-YSR | .11 | .15 | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Adol. Internalizing W4-CDI | .11 | .23 | .67 | - | ||||||||||

| 5. W2 emotional reactivity | .15 | .11 | .27 | .23 | - | |||||||||

| 6. W3 emotional reactivity | .15 | .12 | .30 | .26 | .57 | - | ||||||||

| 7. Adol. externalizing W4-YSR | .10 | .09 | .55 | .43 | .12 | .17 | - | |||||||

| 8. Adol. externalizing W4-Del. | .10 | .14 | .18 | .25 | .15 | .08 | .51 | - | ||||||

| 9. Marital hostility W1 | .25 | .30 | .17 | .17 | .21 | .23 | .19 | .13 | - | |||||

| 10. Adol. Internalizing W1-YSR | .11 | .08 | .44 | .27 | .29 | .22 | .23 | .06 | .14 | - | ||||

| 11. Adol. internalizing W1-CDI | .09 | .07 | .31 | .21 | .24 | .14 | .22 | .13 | .14 | .61 | - | |||

| 12. Adol. externalizing W1-YSR | .08 | .07 | .19 | .15 | .15 | .16 | .37 | .31 | .13 | .54 | .37 | - | ||

| 13. Adol. externalizing W1-Del. | −.04 | .05 | .09 | .08 | .15 | .03 | .25 | .49 | .02 | .26 | .30 | .51 | - | |

| 14. Parental harshness W1 | .17 | .14 | .17 | .20 | .12 | .15 | .29 | .16 | .38 | .19 | .15 | .24 | .02 | - |

| M | 1.32 | 1.35 | 7.92 | 1.87 | 1.51 | 1.39 | 8.57 | 1.15 | 1.83 | 10.96 | 1.31 | 9.47 | 1.10 | 3.61 |

| SD | .30 | .32 | 7.46 | 2.70 | .53 | .50 | 7.40 | .21 | .65 | 7.50 | 2.20 | 5.98 | .13 | 1.27 |

Note. WR = wife reported; HR = husband reported; W = Wave; YSR = Youth Self-report. CDI = Children's Depression Inventory. Bolded correlations are significant at p < .05.

Emotional reactivity

Youths' emotional reactivity to parents' marital conflict was measured using the 9-item emotional reactivity subscale from the Security in the Interparental Subsystem (SIS; Davies et al., 2002) at W2 and W3. Items had a 4-point response format that ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very true of me). Sample items for the stem “When my parents have an argument” included “I feel unsafe” and “I can't seem to calm myself down.” Within each year, items were averaged and a higher score indicated greater emotional reactivity. Cronbach's alphas were good for both years (i.e., > .87).

Internalizing problems

Adolescents' internalizing problems were measured at W4 using the Youth Self-Report (YSR, Achenbach, 1991). Each of the 31 items had a 3-point response format, 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true. Sample items included “feel worthless or inferior,” and “am unhappy, sad, or depressed.” Items were summed and a higher score indicated greater internalizing problems. Cronbach's alpha was .90. W4 internalizing problems also were measured using the 10-item Children's Depression Inventory. A sample item asked youth to think about the past two weeks and select one of the following: “I am sad once in a while, “I am sad many times,” and “I am sad all the time.” Cronbach's alpha was .83. These same measures from W1 were used to control for baseline problems and had good inter-item consistency (greater than .80).

Moderating variables

Perceived youth hopefulness was measured using the 10-item Hopefulness Subscale of the Child/Adolescent Measurement System (Doucette & Bickman, 2001). Youth completed this measure at each wave and scale scores were averaged across the four waves. Cronbach's alphas ranged from .84 to .87. Youth attachment to mother and father was measured using the Inventory of Parent Attachment separately for mothers and fathers at W3 and W4 (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). Cronbach's alphas ranged from .84 to .92. For the present study, two subscale scores of trust and communication were averaged across time for mothers and fathers. At each wave of data collection, mothers and fathers completed the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression measure to assess parental depressive symptoms (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Cronbach's alphas ranged from .85 to .92. Scores were averaged across the four waves to create one score for mothers' depressive symptoms and one score for fathers' depressive symptoms.

Control variables

Adolescents' W4 externalizing problems were measured using the 30-item YSR subscale (Achenbach, 1991). Sample items included “I lie or cheat,” and “I disobey at school.” Items were summed and a higher score indicated greater externalizing problems. Cronbach's alpha was .90. W4 externalizing problems also were measured using youth reports on a 17-item measure of the frequency of delinquent behaviors ever committed (Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985). Examples of items are: “purposely damaged or destroyed property,” and “cheated on a test.” The response format ranged from never (1) to three or more times (3). Items were averaged and Cronbach's alpha was .82. These same measures from W1 were used to control for baseline problems and had inter-item consistency above .80.

Observed marital hostility was included in the model as a control variable so that any associations involving triangulation could be interpreted as unique effects. Observers rated wife's behavior toward husband and husband's behavior toward wife during the problem solving and marital discussion tasks. The following scales were used from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating scales: hostility (e.g., criticism), angry coercion (e.g., hostile control attempts), verbal attack (e.g., demeaning comments), and antisocial (e.g., rudeness) (Melby et al., 1993). In addition, two rating scales were developed for this study: personal attack and yelling. Personal attack includes global criticisms that are directed toward the partner's character. Yelling includes intense, expressed negative affect. Behavior was rated using a 1 (not present) to 9 (mostly characteristic) response format. Cronbach's alpha was .85 for the observed rating composite. Twenty percent of the tasks were selected randomly to be coded by a second coder and the average agreement across raters was .79. Interrater reliability was assessed by calculating single-item intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) based on a one-way random effects ANOVA . The average ICC for this composite measure was .51, which is adequate for these rating scales and comparable to other studies that have used IFIRS ratings (Melby & Conger, 2001).

Observed parental harshness toward youth was included as a control variable so that any associations involving youths' emotional reactivity could be interpreted as reactivity to parents' marital functioning rather than emotional distress resulting from being treated harshly by a parent. Harshness was measured using observer ratings from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby et al., 1993). This variable was included to minimize inaccurate interpretations regarding the mediating role of youths' emotional reactivity to parents' marital conflict and therefore it was not necessary to distinguish mothers' and fathers' harshness. Instead, observer ratings of both mothers' and fathers' harshness toward youth were combined into a 10-item composite measure of parental harshness. Observers' rated mothers' and fathers' W1 hostility and antisocial behavior toward youth during the problem-solving task and their use of harsh discipline (e.g., insulting the youth) as demonstrated or reported during the two parent-child tasks. The rating scales ranged from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 9 (mainly characteristic). Ratings were averaged and higher scores indicated greater parental harshness. Cronbach's alpha was .72 and inter-rater reliability estimated using two observers' ratings of 20% of the interactions tasks was above .70 for most ratings.

Analytic Procedures

Hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM; AMOS 7.0). The adequacy of each SEM model was evaluated using the chi-square statistic and two fit indices. A nonsignificant chi-square indicated a good model fit. However, because of the relatively large sample size, a significant chi-square was expected for most models and two additional fit indices were examined (Byrne, 2001). The comparative fit index (CFI; Bollen & Long, 1993) is based on a comparison of the hypothesized model and the independence model (e.g., there are no relationships between the variables in the model; Byrne, 2001). The CFI ranges from 0 to 1.00 with a cutoff of .95 or higher indicating a well-fitting model and .90 indicating an adequate fit (Byrne, 2001; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Browne and Cudeck's (1993) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) compares the model to the projected population covariance matrix. RMSEA values below .05 indicate good model fit and values between .06 and .08 indicate an adequate fit (Browne & Cudeck; Byrne, 2001).

There was little missing data within each wave (less than 3%). Missing data within and across waves (i.e., attrition) were addressed using full information maximum likelihood estimation methods (FIML). FIML was used because it produces less biased estimates than other methods such as imputing the sample mean or dropping cases for data missing within and across waves (Acock, 2005; Newman, 2003).

Results

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among the variables in the base model are in Table 1. Associations among variables were in the expected directions. Correlations involving the moderating variables can be obtained from the corresponding author.

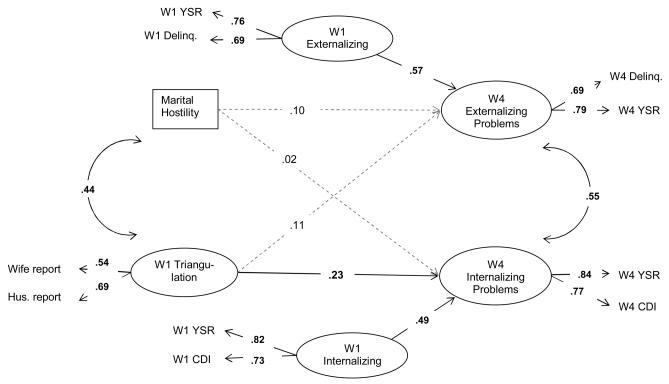

Triangulation and Adolescents' Internalizing Problems

The first hypothesis was that adolescents' triangulation in parents' marital conflict is associated positively with increases in adolescents' internalizing problems, controlling for marital hostility and adolescent externalizing problems (Figure 1). The hypothesis was supported, and the model fit was adequate (χ2 = 115.14, df = 35, p < .001; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .07]. The standardized association between W1 triangulation and increases in adolescents' W4 internalizing problems was .23 (p < .01). The unstandardized estimate was 8.90 (SE = 3.52), indicating that for each unit increase in W1 triangulation, adolescents' W4 internalizing problems increased by 8.90 units on the latent internalizing problem variable that was scaled to the YSR (range 0 to 44). As part of the measurement model, the error covariances were estimated a priori between W1 YSR internalizing and externalizing subscales (r = .53, p < .001), and between W4 YSR internalizing and externalizing subscales (r = .53, p < .001). These significant error covariances were expected due to shared method variance (Bollen & Long, 1993).

Figure 1.

Note. Measurement errors and residuals are not shown to simplify presentation. W1 to W4 = Waves 1 to 4, respectively. YSR = Youth Self-report. CDI = Children's Depression Inventory. Bolded estimates are significant at p < .05.

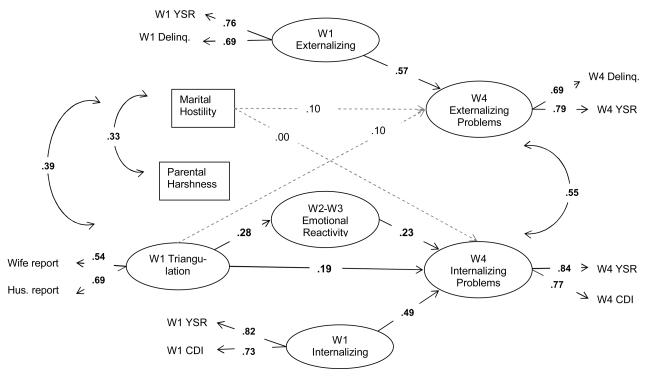

Triangulation, Youths' Emotional Reactivity, and Adolescents' Internalizing Problems

The second hypothesis was that youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict partially mediates the associations between triangulation and adolescents' increases in internalizing problems. This hypothesis was supported, in part (Figure 2), and the model fit was adequate (χ2 = 213.58, df = 64, p < .001; CFI = .90; RMSEA = .075]. W1 triangulation was associated positively W2-W3 youths' emotional reactivity (β = .28, p < .01). Youths' emotional reactivity, in turn, was associated with increases in adolescents' W4 internalizing problems (β = .23, p < .001). The statistical significance of the indirect pathway was tested using Sobel's single-order test, and was significant (Z = 2.37, p < .05). Thus, adolescents' triangulation in parents' marital disputes was associated with adolescents' internalizing problems through youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict across time. The association between W1 triangulation and increases in internalizing problems, however, remained significant (β = .19, p < .05).

Figure 2.

Note. Factor loadings for emotional reactivity not shown to simplify presentation (.68, .86). W1 to W4 = Waves 1 to 4, respectively. YSR = Youth Self-report. CDI = Children's Depression Inventory. Bolded estimates are significant at p < .05.

Moderating Effects

Hypotheses 3 and 4 focused on moderating factors of the indirect pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems. The correlations between moderating variables with other study variables are displayed in Table 2. The effects of each moderator were examined one at a time (i.e., separate analyses) using multiple-group SEM. For each analysis, groups were formed by splitting the sample into lower and higher groups. In separate analyses, several cutting points were used to increase the sensitivity of the analyses. Moderating groups were formed by splitting the sample at the median, at the bottom quartile, and at the top quartile (Sameroff, Martko, Baldwin, Baldwin, & Seifer, 1998).

Table 2.

Correlations of Moderating Variables with Predictors and Outcomes

| Variables | Hope | Maternal Attachment |

Paternal Attachment |

Youth Gender |

Maternal Depres. |

Paternal Depres. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WR W1 triangulation | −.18 | −.10 | −.14 | −.02 | .14 | .08 |

| HR W1 triangulation | −.18 | −.18 | −.17 | .04 | .19 | .32 |

| Ad. internalizing W4-YSR | −.54 | −.28 | −.38 | −.23 | .19 | .05 |

| Ad. Internalizing W4-CDI | −.55 | −.37 | −.48 | −.11 | .19 | .06 |

| W2 emotional reactivity | −.31 | −.10 | −.15 | .03 | .01 | .03 |

| W3 emotional reactivity | −.29 | −.15 | −.10 | −.06 | .07 | −.01 |

| Ad. externalizing W4-YSR | −.44 | −.44 | −.39 | −.05 | .15 | .02 |

| Ad. externalizing W4-Del. | −.31 | −.31 | −.23 | .23 | .10 | −..02 |

| Marital hostility W1 | −.22 | −.09 | −.10 | .02 | .22 | .17 |

| Ad. Internalizing W1-YSR | −.42 | −.14 | −.12 | −.03 | .13 | .13 |

| Ad. internalizing W1-CDI | −.45 | −.25 | −.25 | .00 | .11 | .00 |

| Ad. externalizing W1-YSR | −.34 | −.21 | −.15 | .17 | .16 | .10 |

| Ad. externalizing W1-Del. | −.30 | −.18 | −.14 | .35 | .06 | .06 |

| Parental harshness W1 | −.24 | −.23 | −.24 | .04 | .19 | .13 |

| M | 3.45 | 3.92 | 3.76 | .49 | .47 | .46 |

| SD | .41 | .69 | .70 | .50 | .93 | .94 |

Note. WR = wife reported; HR = husband reported; W = Wave; Ad = Adolescent; YSR = Youth Self-report. CDI = Children's Depression Inventory. Depres. = Depressive symptoms. Bolded correlations are significant at p < .05.

The multiple-group analysis was conducted in two steps. First, the model tested for Hypothesis 2 was estimated across the two moderating sub-groups with all of the statistical parameters (i.e., both measurement and structural parameters) constrained to be the same. Beginning with a fully constrained model minimizes the chance of interpreting the differences inaccurately given all of the remaining parameters are constrained to equality across groups. This analysis produced a chi-square estimate of overall fit for the fully constrained model across two groups. Second, a new model was estimated in which three regression paths (i.e., structural paths) were allowed to vary across the moderating sub-groups: (a) triangulation and youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict, (b) emotional reactivity and adolescents' internalizing problems, and (c) triangulation and internalizing problems. This second analysis produced a chi-square estimate of overall fit for the “partially freed” model across two groups. These two chi-square estimates were compared using the chi-square difference test with three degrees of freedom because three paths were allowed to vary in the second analysis. A significant difference in chi-squares indicated that one of the focal associations differed across the two sub-groups. The specific nature of the difference was identified using the Critical Ratio (C.R.) estimates in AMOS which distribute as Z scores; C.R.s greater than 1.96 were statistically significant (p < .05). The null hypothesis for the C.R. was no difference in a given partialized association between two variables (i.e., the regression coefficient). The alternative hypothesis was a group difference in the two regression coefficients. Once the specific location of the difference was identified, the unstandardized regression coefficients were examined across the two groups to determine the direction of the difference. Finally, a second analysis was conducted in which the factor loadings were allowed to vary across groups. This was done to determine if the significant moderating effects were present regardless of differences in the measurement model (i.e., weak measurement invariance). Significant moderating effects are reported only if they are present both when factor loadings were constrained to equality and when they were allowed to vary across groups.

Youth hopefulness

The third hypothesis was that the pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems, would be weaker for youth with higher levels of hopefulness and attachment to parents. Beginning first with hopefulness, three separate multi-group models were examined to increase the sensitivity of the moderating analyses: splitting the sample into two hopefulness groups at the median, at the bottom quartile, and at the top quartile. The pathway through youths' emotional reactivity was moderated when the sample was split at the bottom quartile of hopefulness (Δχ2 = 96.91, df = 3, p < .001). The association between emotional reactivity and increased internalizing problems was significant for youth with lower levels of hope (b = 26.62, p < .001) but not for youth with higher levels of hope (b = .82, ns). This moderating effect replicated when the sample was split at the median (Δχ2 = 18.66, df = 3, p < .001), but not when the sample was split at the upper quartile (Δχ2 = 4.58, df = 3, p = .21). The critical ratios documenting a significant moderating effect are in Table 3, and the statistical details not reported here (e.g., the median-split regression coefficients) can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Table 3.

Critical Ratios (C.R.) for Moderating Comparisons from Multi-group SEM Analyses

| Moderating Variable | Triangulation and Emotional Reactivity |

Emotional Reactivity and Internalizing Problems |

Triangulation and Internalizing Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hopefulnessa | −1.43 | −3.09** | .18 |

| Maternal Attachmentb | 1.26 | −2.67** | −.87 |

| Paternal Attachmenta | −.24 | −2.27* | 1.26 |

| Youth gender | −1.57 | −1.65 | 1.51 |

| Maternal Depressive Symptoms |

.36 | 1.45 | −.88 |

| Paternal Depressive Symptoms |

−.17 | .59 | .26 |

Note. C.R. greater than or equal to 1.96 were significant at the .05 level; greater than or equal to 2.58 at the .01 level.

Sample split at bottom quartile.

Sample split at median.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Youths' perceived attachment to parents

The moderating effects of youths' attachment perceptions for mothers' and fathers' were examined separately. As with youths' hopefulness, three cutting points were used, in separate analyses, to form groups. Significant moderating effects were present for maternal attachment when using a bottom quartile split (Δχ2 = 9.83, df = 3, p < .05) and a median split (Δχ2 = 10.52, df = 3, p < .05). When split at the bottom quartile of maternal attachment, the association between triangulation and adolescents' internalizing problems was significant for the top 75% of the youth (b = 13.16, p < .01), but not for youth in the bottom 25% (b = −9.06, ns). This difference was present only for youth who scored lowest on maternal attachment because the difference disappeared when the sample was split at the median. Using a median split, the significant group difference shifted to the path from emotional reactivity to adolescent internalizing problems. This path was significant for youth in the bottom half on maternal attachment (b = 5.91, p < .001), but not for youth with scores above the median (b = .98, ns). Thus, youths' perceptions of maternal attachment buffered the deleterious effects of emotional reactivity on increased internalizing problems.

Significant moderating effects also were present for paternal attachment. This statistical significance was present when using a bottom quartile split (Δχ2 = 29.48, df = 3, p < .001). The association between emotional reactivity and increased internalizing problems was stronger for youth with lower levels of paternal attachment (b = 7.22, p < .001) than for youth higher levels of paternal attachment (b = 2.81, p < .01). Thus, youths' perceptions of paternal attachment partially buffered the deleterious effects of emotional reactivity on increased internalizing problems.

Youth gender

The fourth hypothesis was that the pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems, would be stronger for daughters and for youth in families in which parents' have higher levels of depressive symptoms. Although the estimates were in the hypothesized direction for youth gender (i.e., the pathway begin stronger for daughters than for sons), the differences were not statistically significant (Δχ2 = 6.03, df = 3, p = .11).

Parental depressive symptoms

The moderating effects of depressive symptoms for mothers' and fathers' were examined separately. For each analysis, parents with a score of 16 or above on the CES-D during any one of four years were placed in the higher symptom group. A score of 16 or higher was selected because it indicates that an individual is “at risk” for clinical depression. The high depressive symptoms group included 26% of the mothers and 25.7% of the fathers. Yearly percentages of parents at or above 16 on the CES-D ranged from 8.2% through 13.9%.

Beginning with mothers' depressive symptoms, the model with the freed structural paths did not fit the data better than did the fully constrained model (Δχ2 = 4.31, df = 3, p = .23). Fathers' depressive symptoms also was not a statistically significant moderator. The model with the freed structural paths did not fit the data better than did the fully constrained model (Δχ2 = 5.30, df = 3, p = .15). Thus, the process model fit equally well in families with lower and higher levels of parental depressive symptoms.

Discussion

A central focus of this study was to test Bowen's proposition that youths' triangulation into parents' marital conflict is associated with increased offsprings' internalizing problems. We found support for this proposition in a sample of 416 two-parent families during the first half of adolescence. We also tested the hypothesis that youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict mediates the association between triangulation and adolescents' internalizing problems. We found support for an indirect pathway, even when controlling for parental hostility, externalizing symptoms, and parents' harshness toward youth. Finally, we tested the proposition that individual and family characteristics moderate the pathway, triangulation → emotional reactivity → adolescent internalizing problems. We found several moderating effects for the association between youths' emotional reactivity and adolescents' internalizing problems and only one moderating effect for the association between triangulation and youths' emotional reactivity to marital conflict. Assessed one at a time, the association between youths' emotional reactivity and adolescents' internalizing problems was buffered for (a) youth who perceived higher levels of hopefulness, and (b) youth who perceived higher levels of attachment to mothers and fathers. Maternal attachment also moderated the association triangulation and youths' emotional reactivity.

Our finding that adolescents' triangulation in their parents' marital conflict is associated with youths' internalizing symptoms replicates findings by others of the link between triangulation and adolescent internalizing symptoms (Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbush, 1991; Grych et al., 2004; Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996; Wang & Crane, 2001). In addition, the results extend findings from previous studies in a few important ways. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to link triangulation prospectively with increased internalizing symptoms three years later. Previous studies have either been cross-sectional or retrospective in design and have been unable to examine how triangulation impacts subsequent changes in functioning during adolescence. The use of autoregressive controls is a strength of this study. Our findings suggest that triangulation is associated with increases in adolescents' internalizing symptoms three years later, above and beyond their initial level of internalizing symptoms. This longitudinal link supports Bowenian theory positing a developmental pathway whereby parental triangulation of children leads to future internalizing problems (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). It is interesting that the correlation between triangulation and internalizing symptoms is stronger for Wave 4 symptoms than for Wave 1 symptoms. From Bowen's theoretical perspective, to the extent that there is consistency in triangulation over time, the deleterious effects of it should become larger over time because the family process patterns of triangulation become structuralized. Second, previous research has relied primarily on adolescent reporting of all constructs. Our study included both parents and adolescents as reporters and included questionnaire and observational measures, which reduced the problems associated with shared method variance. Third, our study controlled for marital hostility and externalizing symptoms, which demonstrates the greater differential predictive power of triangulation and suggests that triangulation produces specialized effects on internalizing problems rather than having more generalized effects on generic symptomatology. Taken together, this growing body of empirical research strongly supports family systems theory indicating the harmfulness of triangulating adolescents in parental marital conflict. Researchers and clinicians working within the divorce field have long discussed the deleterious impact of involving children in marital conflict (Buchanan, Maccoby & Dornbush, 1991). It is clear that triangulating adolescents also is harmful to adolescents in married families. Thus, clinicians and others who work with families need to assist parents with keeping marital problems within the marital dyad. Adolescent children need to be left out or blocked from parents' marital issues. Parents need to improve their ability to cope with and handle the anxiety associated with marital conflict in other ways that do not involve their children.

Our second hypothesis examined a potential generative mechanism to explain the process whereby involving adolescent children in marital conflict leads to internalizing symptoms. We found that youths' emotional reactivity to parental conflict linked triangulation and increases in subsequent adolescent internalizing symptoms, even when observed parental harshness, marital hostility, and externalizing symptoms were controlled. Bowen (1978) and Minuchin and his colleagues (1975) described children's' responses of emotional dysregulation in response to being caught in parents' marital conflict. Parent conflict and tension is proposed to induce emotional arousal in children, triggering emotional and physiological responses. In families who exhibit patterns of triangulation, this emotional and physiological response is posited to not “turn off” as it does in families with better boundary maintenance. Thus, the child's emotional and physiological response to family conflict is maintained for long periods at a highly aroused level (Minuchin et al., 1975). Triangulation upsets and agitates adolescents and this level of emotional reactivity is associated with increased internalizing symptoms. Triangulation may upset adolescents because adolescents feel compelled to side with one parent against the other and fear, anxiety, tension, resentment, or guilt may result from the boundary violation. Chronic emotional reactivity is likely to keep adolescents' energy focused on maintaining their parents' marriage, rather than investing that energy in typical, individual interests (Bell et al., 2001; Davies & Cummings, 2006). This inappropriate expenditure of developmental energy during the important adolescent period when youth are supposed to be focused on gaining autonomy within the parent-adolescent subsystem may reflect itself in internalizing symptomatology. The applied value of understanding this mediating pathway suggests that clinicians should focus on minimizing adolescents' emotional reactivity to dysfunctional triangulation in parental marital conflicts. Interventions focused on stress management and emotional regulation, which are aimed at reducing adolescents' levels of emotional reactivity, are clearly warranted by our findings.

Although there was a significant pathway from triangulation to increased internalizing problems through youths' emotional reactivity, a significant pathway between wave 1 triangulation and wave 4 internalizing symptoms still remained after the inclusion of emotional reactivity, indicating the impact of other mechanisms in addition to emotional reactivity. Cognitive mechanisms should be explored in future studies including adolescents' appraisals of self blame (Grych & Fincham, 1990) and decreased self-efficacy that may result from getting triangulated into parental conflict as other potential mediating mechanisms in addition to emotional reactivity.

Our final two hypotheses examined individual and family factors that we predicted would amplify or buffer the pathway from triangulation through emotional reactivity to adolescent internalizing symptoms. We found that all three of our proposed protective factors, youth hopefulness, maternal attachment, and paternal attachment, buffered or partially buffered youth from the negative consequences of emotional reactivity. None of the three proposed amplification factors, youth gender, mothers' depressive symptoms, or fathers' depressive symptoms, significantly moderated either the pathway from triangulation to emotional reactivity or the pathway from emotional reactivity to increased internalizing symptoms.

Interestingly, all three protective factors moderated the impact of the second path in our model of triangulation → emotional reactivity → internalizing symptoms. Thus, our findings indicate that the three buffering factors serve to reduce the deleterious impact of the path between adolescents' emotional reactivity and youth internalizing symptoms. Only one of the factors we examined moderated the first path in our model (i.e., between triangulation and emotional reactivity): maternal attachment. The moderating effect of maternal attachment on the association between triangulation and emotional reactivity was the weakest finding of the moderator analyses and was in the opposite direction of our hypothesis. That is, youth who reported the lowest levels of maternal attachment were buffered from the negative consequences of becoming triangulated in parental conflict. This finding disappeared when the sample was split at the median. The finding of few significant moderators in the first link in our model from triangulation to emotional reactivity may indicate that this link is more robust and reflects a more general association for all adolescents. That is, most adolescents, regardless of individual characteristics or family conditions, may react to triangulation with increased emotional reactivity. Only those youth who have extremely poor attachment with their mothers may not react in this manner. These findings suggest that most adolescents are upset when they get triangulated into their parents' marital conflicts; however, not all youth who are upset by the triangulation develop maladaptive symptoms. In addition, these results suggest that the path from emotional reactivity to internalizing symptoms is more contextually dependent, and therefore, potentially more malleable. Interventions designed to help adolescents recognize when they are upset and then to be able to calm themselves may potentially be more efficacious than cognitive strategies aimed at preventing the emotional reactivity in the first place.

Individual characteristics of adolescents as well as characteristics of the family environment buffered the deleterious impact of emotional reactivity to marital conflict. Adolescents who displayed more hopefulness were buffered from the deleterious impact of emotional reactivity. Hope indicates an individual cognitive style and adolescents' cognitive appraisals have been implicated in theories explaining the impact of triangulation on adolescents' psychological functioning (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Grych et al., 2004). Hope reflects an optimistic lens through which adolescents view family interactions and hopeful youth probably interpret family behavioral patterns in more positive ways that are likely to reduce the impact of the distress associated with triangulation, and thus, protect adolescents from the pathogenic impact of triangulation. Attachment to mothers and fathers also buffered the deleterious impact of increased emotional reactivity associated with triangulation. These findings suggest that the quality of the parent-adolescent relationships can help protect adolescents from negative consequences associated with triangulation and the emotional upsettedness it creates. Having secure relational models can serve as important long-term foundations upon which adolescents can rely and which may be more powerful than and buffer adolescents from the impact of other maladaptive current family patterns.

There are several limitations to our findings. First, our sample was not representative of the racial and economic diversity of the United States nor did it include participants from other countries. Other studies have found the link between triangulation and youth internalizing problems in more ethnically and economically diverse samples (Grych et al., 2004), which suggests that other aspects of our findings might generalize more broadly. In addition, investigations have found triangulation linked with poorer developmental outcomes (lower ego development, problem behaviors) in countries outside of the U.S., suggesting some degree of cross-cultural applicability to the pathway for adolescents (Bell et al., 2001; Bradford et al., 2004). Nevertheless, replication of our findings in more diverse samples within the U.S. and with samples from other countries is important. Second, our measure of triangulation assessed adolescents being caught in the middle of their parents' conflicts. It did not measure other types of triangulation such as scapegoating and detouring. The triangulation measure also did not separate parent and youth-initiated triangulation, which might have differential effects on adolescents' mental health (Grych, Fosco, & Hauser, 2008). Future research should investigate the differential impact of various types of triangulation. It is also important to note that the association between triangulation and internalizing symptoms was small. Thus, the investigation of other important predictors of adolescent internalizing symptoms is warranted. Finally, emotional reactivity was assessed solely through youth self-report assessment. The internalizing problems latent construct was assessed using youth indicators as well and raises the possibility that the association between the two variables was inflated by method variance. Future investigations should include physiological measures of emotional reactivity.

In summary, findings from this longitudinal, multi-reporter, multi-method study of adolescents and their parents indicate (a) a pathway from triangulation through emotional reactivity to internalizing problems, and (b) that the part of this pathway from emotional reactivity to adolescents' internalizing problems is moderated by individual and family contextual factors. These findings are important for developing interventions aimed at promoting adolescent functioning because they target several different potential avenues for change. Family-oriented clinicians can intervene at the level of the family or parents by blocking triangulation or by improving the parent-adolescent relationship. They also can intervene by working with the adolescent to reduce emotional reactivity by helping adolescents improve their stress management and emotional self-regulation skills. Future research should include physiological assessment of emotional reactivity to parental conflict and should examine this model with other adolescent outcomes. For example, most research on family conflict in general and triangulation in particular has examined its link with adolescent psychological functioning. The relational context in which the triangulation is occurring suggests that adolescents' future relational functioning also may be deleteriously impacted by triangulation. Future research should examine the impact of triangulation on adolescents into parental marital conflict on adolescents' social relationships with close friends and romantic partners.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from The National Institute of Mental Health, R01-MH59248 to the first author. We thank the staff of the Family Life Project for their unending contributions to this work and the youth, parents, teachers, and school administrators who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/journals/fam.

Contributor Information

Cheryl Buehler, University of North Carolina - Greensboro.

Deborah P. Welsh, University of Tennessee

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report form and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Acock A. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TD. ‘Feeling caught’ in stepfamilies: Managing boundary turbulence through appropriate communication privacy rule. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:729–755. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G, Bell K. Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Development. 1998;69:1406–1419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Afifi TD. Feeling caught between parents: Adult children's relations with parents and subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:222–235. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell LG, Bell DC, Nakata Y. Triangulation and adolescent development in the U.S. and Japan. Family Process. 2001;40:173–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Long JS. Testing structural equation models. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aaronson; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K, Barber BK, Olsen JA, Maughan SL, Erickson LD, Ward D, Stolz HE. A multi-national study of interparental conflict, parenting, and adolescent functioning: South Africa, Bangladesh, China, India, Bosnia, Germany, Palestine, Columbia, and the United States. Marriage and Family Review. 2004;35(3-4):107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bryne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbush SM. Caught between parents: Adolescents' experience in divorced homes. Child Development. 1991;62:1008–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Lange G, Franck KL. Adolescents' cognitive and emotional responses to marital hostility. Child Development. 2007;78:775–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles R. Is there any empirical support for Bowen's concept of differentiation of self, triangulation, and fusion? American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Harter K. Interparental conflict and parent-child relationships. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development. Cambridge University Press; New York: NY: 2001. pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Conger RD, Lorenz FO. Predicting change in adolescent adjustment from change in marital problems. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:812–823. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77:132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Interparental discord, family process, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2nd ed. Wiley & Sons; New York: 2006. pp. 86–128. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Forman EM, Rasi JA, Stevens KI. Assessing children's emotional security in the interparental relationship: The Security in the Interparental Subsystem Scales. Child Development. 2002;73:544–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67(3):vii–viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay LL. Interparental conflict and adolescent adjustment: Why does gender moderate early adolescent vulnerability? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:160–170. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Winter MA, Cicchetti D. The implications of emotional security theory for understanding and treating childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:707–735. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette A, Bickman L. Child Adolescent Measurement System: User Manual. The Center for Mental Health Policy; Vanderbilt University: 2001. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Cho E, Kraemer HC. Exposure to maternal depression and marital conflict: Gender differences in children's later mental health symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(6):728–737. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046849.56865.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Understanding the association between marital conflict and child adjustment: Overview. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment: A longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:951–975. [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Eckenrode J. Context and process in research on risk and resilience. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. Cambridge University Press; NY: 1996. pp. 19–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fosco GM, Hauser JK. Paper presented at the biannual conference of the Society for Research on Adolescence. Chicago, IL: Mar, 2008. Child involvement, triangulation and boundary maintenance: Distinctions and implications for child and family functioning. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Harold GT, Miles CJ. A prospective investigation of appraisals as mediators of the link between interparental conflict and child adjustment. Child Development. 2003;74:1176–1193. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Raynor SR, Fosco GM. Family processes that shape the impact of interparental conflict on adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:649–665. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Seid M, Fincham FD. Assessing marital conflict from the child's perspective: The Children's Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Devleopment. 1992;63:558–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Shelton KH, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings ME. Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships and child adjustment. Social Development. 2004;13:350–376. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Sherman L, Biglan A. Maternal depression, marital discord, and children's behavior: A developmental perspective. In: Patterson GR, editor. Depression and aggression in family interaction. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. Academic Press; New York: 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz DB, Bush NF. Reconstructions of family relationships: Parent-child alliances, personal distress, and self-esteem. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:732–743. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobvitz D, Hazen N, Curran M, Hitchens K. Observations of early triadic family interactions: Boundary disturbances in the family predict symptoms of depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:577–592. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404004675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The conflicts and problem-solving scale. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(4):454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr ME, Bowen M. Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. W. W. Norton & Co; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory CDI Manual. Multi-Health Systems, Inc; Toronto: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future use. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis E,B, John RS. Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:3–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Garmezy N. Risk, vulnerability, and proective factors in developmental psychopathology. In: Lahey BB, Kazdin AA, editors. Advances in clinical child psychology. Vol. 8. Plenum; NY: 1985. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows LA, Kaslow NJ, Thompson MP, Jurkovic GJ. Protective factors against suicide attempt risk among African American women experiencing intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby J, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, Ahrens K, Black D, Brown D, Huck S, Mutchler L, Rogers S, Ross J, Stavros T. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. 4th edition. Center for Family Research in Rural Mental Health; Iowa State University, Ames: 1993. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RB, Anderson S, Keala DK. Is Bowen theory valid?: A review of basic research. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30:453–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S, Baker L, Rosman BL, Liebman R, Milman L, Todd TC. A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children. Family organization and family therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:1031–1038. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760260095008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6:328–362. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Bartko WT, Baldwin W, Baldwin C, Seifer R. Family and social influences on the development of child competence. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Families, risk, and competence. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1998. pp. 161–186. [Google Scholar]

- Schludermann E, Schludermann S. Replicability of factors in the Children's Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) Journal of Psychology. 1970;96:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ. Societal change and change in family violence from 1975 to 1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet J, Bumpass L. National Survey of Families and Households. 2005 http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/

- Sweet J, Bumpass L, Call V. The design and content of The National Survey of Families and Households. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin; Madison: 1998. NSFH Working Paper #1. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Helms HM, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Thayer SM, Sales LH. Who's the boss? Patterns of perceived control in adolescents' friendships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:403–421. [Google Scholar]