Abstract

Perturbation of lipid second messenger networks is associated with the impairment of synaptic function in Alzheimer disease. Underlying molecular mechanisms are unclear. Here, we used an unbiased lipidomic approach to profile alkylacylglycerophosphocholine second messengers in diseased tissue. We found that specific isoforms defined by a palmitic acid (16:0) at the sn-1 position, namely 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 PAF) and 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 lyso-PAF), were elevated in the temporal cortex of Alzheimer disease patients, transgenic mice expressing human familial disease-mutant amyloid precursor protein, and human neurons directly exposed to amyloid-β42 oligomers. Acute intraneuronal accumulation of C16:0 PAF but not C16:0 lyso-PAF initiated cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated hyperphosphorylation of tau on Alzheimer disease-specific epitopes. Chronic elevation caused a caspase 2 and 3/7-dependent cascade resulting in neuronal death. Pharmacological inhibition of C16:0 PAF signaling, or molecular strategies increasing hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF, protected human neurons from amyloid-β42 toxicity. Together, these data provide mechanistic insight into how disruptions in lipid metabolism can determine neuronal response to accumulating oligomeric amyloid-β42.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, glycerophosphocholine, lipidomics

The aberrant processing of the amyloid precursor protein to different assemblies of amyloid β (Aβ) peptides ranging from 37 to 42 amino acids is an early and necessary prerequisite for the development of Alzheimer disease (AD) (1). The “amyloid cascade hypothesis” defines generation of these smaller, toxic Aβ fragments, specifically soluble Aβ42 oligomers, as the root cause of AD (1). The severity of AD progression, however, is highly correlated with the rate of abnormal tau processing (2). Underlying molecular mechanisms linking Aβ42 biogenesis to the aggregation of normally soluble tau proteins into hyperphosphorylated oligomers remain elusive.

Aβ42 can activate cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) (3, 4), a Group IVa PLA2 that preferentially hydrolyzes arachidonic acid from the sn-2 position of 1-O-alkyl-2-arachidonoyl- and 1-O-acyl-2-arachidonoyl-glycerophospholipids (5). Inhibiting cPLA2 activation completely attenuates Aβ42 neurotoxicity; blocking the different metabolic arms of the arachidonic acid cascade confers only partial protection (3, 4, 6). Little is known about the fate of the glycerophospholipid backbone following the release of arachidonic acid by cPLA2, although accumulation of choline-containing lipids is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in AD (7, 8). The alkyl-lyso-glycerophosphocholines and lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) are of particular interest (Fig. S1). These metabolites are biologically active in their own right and can be further modified by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferases (LPCATs). LPCAT activity also increases in AD (9), notably in the posterior-temporal entorhinal cortex, a region characterized by the earliest tau pathology (2). Transfer of a long-chain acyl group to the sn-2 position by LPCAT1 and LPCAT2 regenerates structural membrane lipids, whereas addition of a small acetyl group produces a family of powerful lipid second messengers known as platelet activating factors (PAFs) (10, 11).

Here, we used an unbiased lipidomics approach to identify metabolic disruptions in alkylacylglycerophosphocholine second messengers in the posterior-entorhinal cortex of individuals with AD, TgCRND8 transgenic mice, as well as human neurons directly exposed to soluble Aβ42 oligomers. We found that Aβ42 triggers a selective destabilization in Land's cycle metabolites defined by a palmitic acid (16:0) at the sn-1 position. The acute accumulation of 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 PAF), but not its immediate precursor and metabolite 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 lyso-PAF), signals the phosphorylation of tau at AD-specific epitopes. Chronic elevation activates an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated calpain and caspase cascade compromising neuronal viability. Strategies that either promote the hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF or inhibit downstream signal transduction pathways protect neurons from Aβ42 toxicity and prevent aberrant tau processing.

Results

Alkylacylglycerophosphocholine Metabolism Is Disrupted in AD.

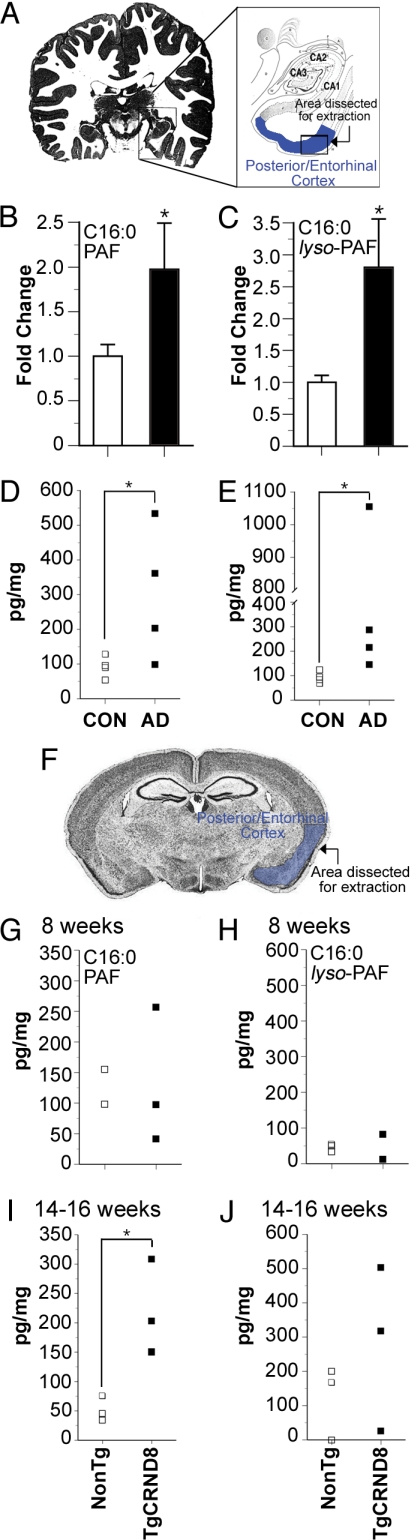

Glycerophospholipids were extracted postmortem from the posterior/entorhinal cortex of AD patients and control subjects (Fig. 1A). PAF isoforms were profiled by high-performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) (12). Lipids with mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of 450–600 were analyzed in positive ion mode by MS scan for a protonated molecule at expected m/z followed by precursor ion scan for a diagnostic phosphocholine product ion at m/z 184. Peak intensities were standardized against C13:0 LPC, a synthetic internal standard added at the time of lipid extraction. Nineteen alkylacylglycerophosphocholine species were identified (Figs. S2 and S3). Three of these species were significantly elevated in AD cortex: 1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 PAF), its immediate metabolite/precursor 1-O-hexadecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C16:0 lyso-PAF), and 1-O-oleyl-2-lyso-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C18:1 lyso-PAF) (Fig. 1 B and C and Figs. S2 and S3). As elevations in both C16:0 PAF and C16:0 lyso-PAF suggested a specific disruption in the remodeling of palmitic acid containing-PAFs, we used deuterated standards to quantify tissue concentrations. Clear separation was obtained between C16:0 PAF and isobaric C18:0 LPC with the isoform altered in AD co-eluting with d4-C16:0 PAF (Fig. S4). Tissue concentrations, expressed as pg/mg in Fig. 1 D and E, represent approximate molar concentrations of 258 ± 30 pM increased to 639 ± 205 pM for C16:0 PAF and 316 ± 25 pM increased to 1035 ± 455 pM for C16:0 lyso-PAF in control and AD cortex, respectively.

Fig. 1.

C16:0-PAF and its immediate precursor and metabolite C16:0-lyso-PAF accumulate in posterior temporal/entorhinal AD cortex and TgCNRD8 mice. (A) Alkylacylglycerophosphocholines in postmortem human posterior-entorhinal cortex were profiled by LC-ESI-MS (Figs. S2 and S3). (B) C16:0 PAF and (C) C16:0 lyso-PAF levels were elevated in AD tissue (n = 4 individuals/condition). Data are expressed as fold change relative to controls ± SEM. Tissue concentrations, expressed as pg/mg tissue wet weight, were calculated for (D) C16:0 PAF and (E) C16:0 lyso-PAF in comparison to deuterated samples spiked at the time of analysis (Fig. S4). Each square represents an individual patient (* indicates P < 0.05, Student's t test). (F) Dissection coordinates (blue) of regions analyzed by LC-ESI-MS in TgCRND8 and NonTg control mice. Quantification of C16:0 PAF and C16:0 lyso-PAF species was performed at 8 weeks of age in panels G and H and at 14–16 weeks of age in panels I and J by standard addition (n = 15 measurements/sample, *, P < 0.05, Student's t test, n = 3 mice/condition).

Disruption of C16:0 PAF Metabolism Is Detected in Symptomatic TgCRN8 Mice.

To establish the kinetics of palmitic-PAF metabolic disruption, we analyzed the posterior temporal/entorhinal cortex of TgCRND8 transgenic mice (Fig. 1F). TgCRND8 mice express a double mutant form (KM670/671NL+V717F) of the human amyloid precursor protein gene under the control of the prion protein promoter. Increases in cortical Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios are initially observed at 10–12 weeks of age coincident with learning and memory impairment (13). We found that cortical levels of C16:0 PAF and C16:0 lyso-PAF of TgCRND8 mice were comparable to nontransgenic (NonTg) littermates at 8 weeks of age (Fig. 1 G and H), yet were 4-fold and 2-fold higher, respectively, by 14–16 weeks of age (Fig. 1 I and J). Tissue concentrations, expressed as pg/mg in Fig. 1 I and J, represent approximate molar concentrations of 104 ± 25 pM C16:0 PAF in NonTg increased to 407 ± 105 pM in TgCRND8 and 268 ± 135 pM C16:0 lyso-PAF in NonTg increased to 597 ± 320 pM in 14- to 16-week-old TgCRND8 mice.

Intracellular Accumulation of C16:0 PAF Signals Aβ42 Neurotoxicity.

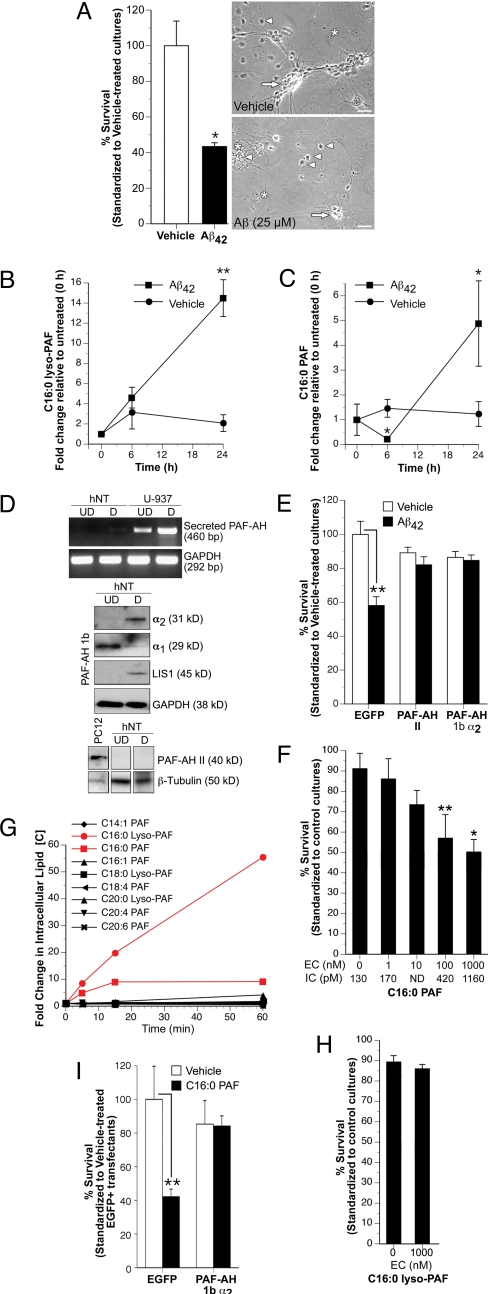

To determine whether Aβ42 directly disrupts C16:0 PAF metabolism in human neurons, hNT neurons were treated with Aβ42 (25 μM) prepared as soluble oligomers (14). A 24-h exposure signaled neuronal loss (Fig. 2A). Over the course of treatment, neuronal C16:0 lyso-PAF concentrations increased steadily rising to 15-fold that of control cultures (12 ± 0.1 pM to 180 ± 8 pM) (Fig. 2B). Endogenous neuronal C16:0 PAF levels initially dropped from approximately 127 ± 27 pM to 28 ± 4 pM over the first 6 h of treatment and then increased to 5-fold that of control levels within 24 h (619 ± 115 pM) (Fig. 2C). These data are consistent with a specific increase in Land's cycle remodeling of palmitic acid-PAFs in response to oligomeric Aβ42. Also intriguing was the transient decrease in endogenous C16:0 PAF levels suggesting a compensatory increase in intracellular catabolism following acute Aβ42 exposure.

Fig. 2.

C16:0 PAF accumulates in human neurons treated with soluble Aβ42 oligomers compromising neuronal viability (A) A 24-h exposure to soluble Aβ42 oligomers (25 μM) elicited neuronal death as assessed by TUNEL (Left, *, P < 0.05, Student's t test, n = 6–10 independent cultures/condition). The morphology of single hNT neurons (arrowhead) or aggregated in bundles (arrows) on non-neuronal cells (asterisk) is shown after 24-h treatment with vehicle (Top Right) or Aβ42 (Bottom Right). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (B) Treatment with 25 μM Aβ42 oligomers increased intraneuronal C16:0 lyso-PAF levels. (C) A transient decrease in C16:0 PAF was detected within 6 h of treatment followed by a progressive increase (*, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). Data are expressed as fold change relative to untreated hNT control cultures grown in complete media ± SEM (n = 4 cultures/condition). (D) Undifferentiated (UD) and differentiated (D) hNT cultures do not express secreted/plasma PAF-AH mRNA (RT-PCR). Positive controls were human U-937 cells (UD) and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-treated U-937 cells differentiated to a macrophage lineage (D). GADPH was amplified from the same random-primed cDNA to confirm template integrity. All three PAF-AH I subunits were detected in both undifferentiated (UD) and differentiated (D) hNT cultures by Western analysis. Only optimal exposure times are presented to show differences in expression between UD and D cultures. GAPDH was used as a loading control (Lower). PAH-AH II protein was not detected in hNT cultures. The positive control (+) was PC12 cells. β-tubulin was used as a loading control (Lower). (E) Transfection of hNT neurons with either PAF-AH II or PAF-AH I α2 and EGFP, but not empty vector, and EGFP-protected hNT neurons from a 24-h exposure to 25 μM Aβ42 (*, P < 0.05, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). (F) Elevating intracellular C16:0 PAF concentrations to >400 pM/cell in the absence of any other toxic stimuli compromised neuronal viability as assessed by TUNEL 24 h after treatment. EC, extracellular, IC, intracellular concentration. ICs were determined by LC-ESI-MS. Viability was standardized to untreated-control cultures (*, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). (G) Intraneuronal alkylacylglycerophosphocholine metabolites were profiled by LC-ESI-MS following direct exposure to 1 μM C16:0 PAF. No significant change in any other PAF species was observed in C16:0 PAF-treated hNT neurons beyond the expected elevation in intracellular C16:0 PAF and a progressive increase in C16:0 lyso-PAF. (H) C16:0 lyso-PAF did not compromise neuronal viability as assessed by TUNEL. (I) Increasing cytosolic PAF hydrolysis protected hNT neurons from 24 h C16:0 PAF challenge. Cultures were transfected with EGFP and empty vector or EGFP and PAF-AH I α2 (**, P < 0.01, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). All treatments were carried out in serum-free media containing 0.025% BSA. No degradation of exogenous PAF in media was detected under these conditions (Fig. S8a).

To provide mechanistic insight, we sought to modulate the Aβ42-triggered increase in C16:0 PAF metabolism with minimal perturbation of other lipid networks. Because genetic, molecular, and pharmacological strategies targeting cPLA2, LPCAT1, or LPCAT2 will also impinge upon the arachidonic acid cascade, phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylglycerol remodeling, as well as structural membrane lipid composition, we used a gain-of-function approach to promote hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF. PAF-AHs cleave the sn-2 acetyl chain of PAF alkylacylglycerophosphocholines generating alkyl-lyso-glycerophosphocholines (lyso-PAFs) (Fig. S1). There are three PAF-AH isoforms. The 45-kDa secreted PAF-AH isoform is not expressed by hNT neurons (Fig. 2D). Cytosolic PAF-AH II is also is not expressed by hNT neurons (Fig. 2D). Cytosolic PAF-AH Ib is an acetylhydrolase-specific complex composed of two 29-kDa α1 and/or 30-kDa α2 catalytic subunits and two 45-kDa regulatory LIS1 subunits (15). We have previously shown that overexpression of the α2 catalytic subunit enhances PAF hydrolysis in cells that endogenously express all three PAF-AH Ib subunits (16). As observed over the course of CNS development (17), the α1 catalytic subunit was detected at higher levels before differentiation, while the α2 catalytic and LIS1 regulatory subunits were maximally expressed following terminal differentiation of hNT neurons (Fig. 2D). Based on this profile, neurons were transfected with EGFP and empty vector, EGFP and PAF-AH II, or EGFP and PAF-AH I α2. Neurons ectopically expressing PAF-AH II or overexpressing the PAF-AH I α2 catalytic subunit were protected from Aβ42 (Fig. 2E).

These findings implicated C16:0 PAF and not C16:0 lyso-PAF in Aβ42 toxicity. To test this directly, we used a biochemical loading approach to elevate intraneuronal C16:0 PAF concentrations in the absence of any other toxic stimuli. PAFs can be internalized following binding to PAFR and clatherin-mediated endocytosis, transglutaminase-dependent transmembrane bilayer movement, engagement with low affinity binding sites at the plasma membrane, or direct physicochemical effects at the plasma membrane (16, 18, 19). As hNT neurons do not express PAFR (Fig. S5a), we established the kinetics of PAFR-independent PAF lipid internalization using a Bodipy fluorophore-labeled isoform [1-(O-[11-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-proprionyl)amino]undecyl)-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; C11:0 B-PAF]. A progressive increase in cell-associated C11:0 B-PAF was observed over the first 60 min of lipid addition to media (Fig. S6a). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) of lipid loosely associated with the neuronal plasma membrane (acid-labile fractions), intracellular lipid (acid-resistant fractions), and lipid present in extracellular milieu revealed that cell-associated C11:0 B-PAF was rapidly internalized within 5 min (Fig. S6b). An increase in hydrolysis was observed within 15 min with the C11:0 B-lyso-PAF metabolite released into the extracellular milieu (Fig. S6b). This balance between lipid internalization and lipid hydrolysis maintained a constant elevated intracellular concentration of C11:0 B-PAF for at least 60 min (Fig. S6b). Conversely, when hNT neurons were loaded with lyso-PAF, C11:0 B-lyso-PAF was rapidly internalized but converted to C11:0 alkylacylglycerophosphocholine and not C11:0 B-PAF (Figs. S6c and S7). Preferential conversion of C11:0 lyso-PAF to C11:0 B-PAF was only observed when neurons were treated in the presence of Aβ42 (Fig. S7).

We exploited this loading approach to elevate acutely C16:0 PAF and C16:0 lyso-PAF levels in hNT neurons without directly impacting on other glycerophosphocholine second messengers. Intracellular lipid concentrations were determined by LC-ESI-MS and neuronal viability was assessed by TUNEL after a 24-h exposure. Significant neuronal death was only observed when intracellular C16:0 PAF levels reached molar concentrations comparable to those detected in postmortem AD tissue, 14- to 16-week-old TgCRND8 mice, and Aβ42-treated hNT neurons (i.e., >400 pM/cell) (Fig. 2F). To establish specificity, fold changes in other changes in other endogenous alkylacylglycerophosphocholine concentrations were profiled and quantified by LC-ESI-MS. Nine PAF species were identified in human neurons. No significant change in any other isoform was observed beyond the expected sustained elevation in the target lipid and a progressive increase in C16:0 lyso-PAF likely the result of compensatory hydrolysis (Fig. 2G). Only direct 24-h application of C16:0 PAF (Fig. 2F) not C16:0 lyso-PAF (Fig. 2H) signaled neuronal death. To demonstrate that neurotoxicity was not the result of nonspecific lytic effects of extracellular PAF, plasma membrane integrity was assessed using ethidium bromide homodimer (EthD-1), a membrane impermeant dye. Direct application of C16:0 PAF to hNTs did not increase EthD-1 uptake over a 24-h treatment period (Fig. S8b). Loss in membrane integrity was only observed using methyl-carbamyl PAF (mc-PAF), a PAF analog resistant to hydrolysis, applied to hNT neurons at concentrations that exceeded critical micelle concentration (2.5–5 μM) (Fig. S8c). These data provided converging evidence that intraneuronal accumulation of C16:0 PAF signals a loss of viability in human neurons. To confirm these data, hNT neurons were transfected with EGFP and empty vector or EGFP and PAF-AH I α2 and treated with 1 μM C16:0 PAF. As observed in Aβ42-treated cultures (Fig. 2E), enhancing cytosolic hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF prevented neuronal loss (Fig. 2I).

Chronic C16:0 PAF Accumulation Induces an ER Stress-Dependent Calpain/Caspase Cascade.

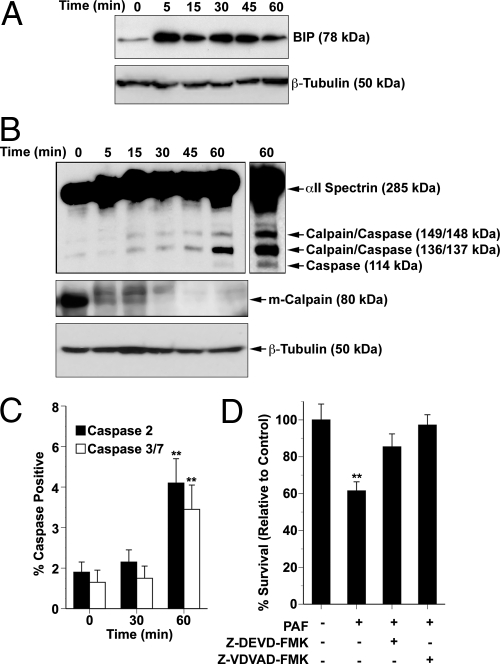

To establish how intraneuronal C16:0 PAF accumulation signals Aβ42 toxicity, we first assessed calcium influx. A 180-s exposure to C16:0 PAF or C16:0 lyso-PAF did not acutely elevate intraneuronal calcium levels in the absence of PAFR as would be expected by a receptor-mediated event (Fig. S5b). We next assessed ER stress responses. In murine neurons, Aβ42 activates both calpains and ER-associated caspase-12 (20). The human homolog of caspase-12 has a frameshift mutation resulting in a premature stop codon and an amino acid substitution within a critical site for caspase enzymatic activity, rendering it catalytically inactive (21). Caspase 2 is a candidate human ER caspase, while caspase 7 translocates to the ER following apoptotic challenge (22). To test whether rising C16:0 PAF levels impair ER function, we assessed changes in BIP (GRP78) expression. BIP increased rapidly in hNTs in response to C16:0 PAF loading (Fig. 3A). ER stress-associated calpain/caspase activation was next assessed by examining spectrin cleavage. Spectrin is a scaffold protein that anchors the plasma membrane to the cytoskeleton. The kinetics of cleavage can be used to track sequential calpain/caspase activation. Proteolytic processing by calpains (m and μ) yields 149- and 136-kDa fragments, whereas caspase 2, 3, and 7 cleavage yields 148- and 137-kDa fragments. Both the calpain/caspase-generated 148/149-kDa fragments can be further processed to 114-kDa and 34-kDa products by caspases 3/7 but not caspase 2 (23). We observed an increase in spectrin cleavage, generating both 148/149-kDa and 136/137-kDa fragments, 15 min after C16:0 PAF application (Fig. 3B). A further increase in the levels of the 136/137-kDa fragment was observed within 60-min coincident with the appearance of the caspase 3/7-specific product (Fig. 3B). To confirm these data, calpain and caspase activation were assessed directly. Activation of m-calpain is associated with cleavage of the 80-kDa calpain pro-protein (24). Using an antibody that detects the inactive pro-protein but not the cleaved product, a marked decrease in pro-m-calpain levels was detected 5–45 min after C16:0 PAF challenge consistent with activation (Fig. 3B). By direct enzyme assay, significant caspase 2 and caspase 3/7 activation was only observed at 60 min, following calpain activation (Fig. 3C). To establish whether this calpain-caspase signaling pathway was sufficient to compromise neuronal viability, hNT neurons were treated with C16:0 PAF in the presence of the caspase 2 inhibitor Z-VDVAD-FMK or the caspase 3/7 inhibitor Z-DEVD-FMK. Inhibiting either caspase 2 or caspase 3/7 protected hNTs from C16:0 PAF neurotoxicity (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Intracellular accumulation of C16:0 PAF elicits ER stress and activates m-calpain and caspases 2 and 3/7. (A) Representative immunoblots of three independent experiments showing induction of BIP within 5 min of hNT exposure to 1 μM C16:0 PAF. (B) The same hNT protein lysates were immunoblotted for αII-spectrin and m-calpain using β-tubulin as a loading control. Cleavage fragments generated by calpains (149, 136 kDa) and caspases (148, 137, 114 kDa) are indicated. (C) hNT neurons were treated with 1 μM PAF for 0, 30, and 60 min, and caspase activity was assessed using FAM-VDVAD-FMK (caspase 2) or FAM-DEVD-FMK (caspase 3/7). Data represent the percentage of cells positive for activated caspases (**, P < 0.01, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). (D) Functional dependence of C16:0 PAF-induced neuronal apoptosis on caspase activation was measured by LIVE/DEAD assay. Inhibiting caspase activation protected hNT neurons from elevated intraneuronal accumulation of C16:0 PAF (*, P < 0.05, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test).

Acute Intracellular Accumulation of C16:0 PAF Activates Tau Kinases and Signals Tau Phosphorylation at AD-Specific Phosphoepitopes.

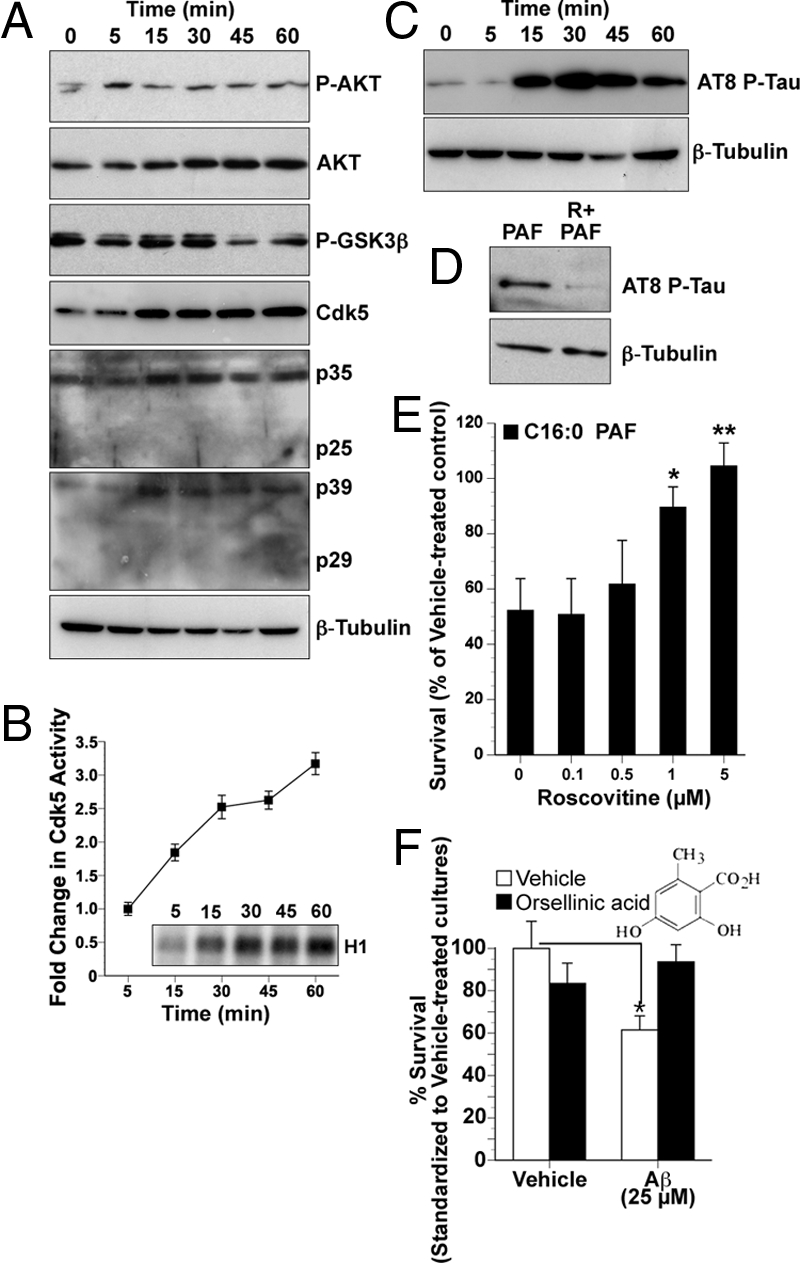

Calpains can activate “tau kinases,” including glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) (25, 26). Alkylacylglycerophosphocholine second messengers have already been shown to stimulate GSK3β activity (27). Their impact on Cdk5 or tau has not been examined. Here, we assessed indicators of both tau kinase activation and inhibition in hNTs loaded with C16:0 PAF. A transient increase in phosphorylation of the GSK3β regulator AKT at Thr-308, commonly associated with the inhibition of GSK3β activity, was observed after 5 min (Fig. 4A). These changes were followed by an activity-associated decrease in GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser-9 after 45 min (Fig. 4A). These data indicate that GSK3β is not activated within the first 45 min of intracellular C16:0 PAF accumulation. More rapid increases in the levels of Cdk5 and its activators p35 and p39 were observed within 15 min of C16:0 PAF application (Fig. 4A). Despite apparent m-calpain activation (Fig. 3B), cleavage of p35 and p39 to the more potent p25 and p29 Cdk5 activators was not detected (Fig. 4A). This p25/p29-independent induction of Cdk5 activity, as a result of acute C16:0 PAF accumulation, was validated by assessing transfer of radiolabeled P32 to histone-1 following immunoprecipitation of Cdk5 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Aβ42-induced accumulation of C16:0 PAF induces Cdk5 and GSK3β activity leading to increased phosphorylation of tau on AD-associated epitopes with associated neurotoxicity inhibited by orsellinic acid. (A) Protein (15 μg) from hNT cells treated with 1 μM C16:0 PAF for 0 (control), 5, 30, 45, or 60 min were immunoblotted to assess kinase expression and posttranslational modifications of effecter proteins. Increases in protein expression of Cdk5 and its activators p35 and p39 were detected within 15 min. A decrease in phospho-GSK3β, associated with activation, was observed by 45 min. A transient increase in phosphorylation of AKT at Thr-308 was observed within 5 min. (B) A progressive increase in Cdk5 activity in hNTs following treatment with 1 μM C16:0 PAF was directly determined by in vitro assay of P32-labeled histone 1 by immunoprecipitated Cdk5 protein (Inset). Quantification was performed by densitometry. (C) Phosphorylation of tau on AD-associated epitopes was observed by Western analysis following C16:0 PAF treatment using the AT8-phospho-specific antibody. (D) Inhibition of Cdk5 with 5 μM roscovitine prevented C16:0 PAF-mediated AT8-reactive tau phosphorylation. β-tubulin immunoblots were used as loading controls. Data are representative of replicate experiments. (E) Roscovitine protected hNT neurons from a 24-h treatment with 1 μM C16:0 PAF as assessed by LIVE/DEAD assay (n = 15 wells per culture conducted in replicate experiments, **, P < 0.01, *, P < 0.05, ANOVA, post-hoc Dunnett's t test). (F) The C16:0 PAF inhibitor orsellinic acid (5 μM) protected hNT cultures from a 24-h treatment with 25 μM Aβ42 (n = 20 coverslips per culture conducted in replicate experiments, ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test, **, P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control).

To evaluate AD-associated tau phosphorylation, we examined two of the main sites aberrantly phosphorylated in AD brain (Ser-202 and Thr-205) (28). AT8-reactive sites were phosphorylated within 15 min of C16:0 PAF exposure (Fig. 4C). To establish whether phosphorylation was mediated by Cdk5, cultures were treated with a general Cdk5/p35 inhibitor roscovitine. Roscovitine prevented the C16:0 PAF-dependent phosphorylation of tau on AD-specific epitopes (Fig. 4D) and protected hNT neurons from C16:0 PAF toxicity (Fig. 4E).

Pharmacological Inhibition of Intracellular C16:0 PAF Signaling Protects Human Neurons from Aβ42 Oligomers.

Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that a pathogenic accumulation of C16:0 PAF in response to oligomeric Aβ42 participates in signaling the hyperphosphorylation of tau and, ultimately, causes caspase-dependent neuronal death. However, pharmacological strategies targeting C16:0 PAF must also consider the amnesiatic impact of PAFR inhibition on learning and memory (29, 30). PAFR is expressed by subpopulations of neurons, notably in the hippocampus (30). Thus, strategies to inhibit C16:0 PAF signaling must be able to pharmacologically distinguish between PAFR-dependent (neuroprotective/functional) and PAFR-independent (neurotoxic) PAF pathways. Orsellinic acid is a fungal-derived benzoic acid that inhibits C16:0 PAF-induced ER caspase activation without affecting PAFR-neuroprotective signal transduction (31). As with gain-of-function approaches to promote C16:0 PAF hydrolysis and restore physiological intracellular concentrations (Fig. 2 E and I), inhibition of intracellular PAF signal transduction with orsellinic acid protected hNT neurons from Aβ42 toxicity (Fig. 4F). As a control, we treated cells with the PAFR antagonist (and structural PAF analog) CV3988. CV3988 did not impact on C16:0-mediated tau phosphorylation in PAFR-negative human neurons or Aβ42 toxicity (Fig. S5d).

Discussion

In this study, we elucidate a pathway of neuronal dysfunction triggered by aberrant alkylacylglycerophosphocholine metabolism in response to oligomeric Aβ42. Our unbiased lipidomics approach revealed a selective disruption of C16:0 PAF and C16:0 lyso-PAF metabolism in the posterior/entorhinal cortex of AD patients. We found that this disruption occurred following pathogenic increases in cortical Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios (13) in TgCRND8 transgenic mice and could be elicited directly in human neurons by exposure to soluble Aβ42 oligomers. Acute elevations of C16:0 PAF signaled tau phosphorylation on AD-specific phospho-epitopes. Chronic elevations initiated calpain and caspase-dependent neuronal death. Through gain-of-function and pharmacological inhibitory approaches, we found that human neurons can be protected from Aβ42 either by enhancing hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF or inhibiting C16:0 PAF-dependent intracellular signal transduction.

Although consistent with the upregulation in cPLA2 and LPCAT activities observed in AD and in response to Aβ42 (3, 4, 9), the specificity of this metabolic disruption was nonetheless surprising. Disruption in the Land's cycle predicts a general increase in PAF metabolism not the hydrolysis of structural lipids with specific carbon chain lengths (Fig. S1). It may be that the accumulation of hexadecyl-PAFs indicates a shift in substrate availability in diseased tissue consistent with a larger metabolic disruption in lipid metabolism. The loss of apolipoprotein E, for example, a risk factor associated with AD, alters the traffic of polyunsaturated lipids from astrocytes to neurons, biasing the composition of long-chain fatty acids in synaptosomes phosphocholines toward hexadecyl (16:0) species in null-mutant mice (32). Furthermore, the calcium-independent PLA2γ (iPLA2γ) isoform, capable of hydrolyzing both sn-1 and sn-2 unsaturated fatty acid chains, shows specificity for palmitic acid-containing carbon chains. iPLA2 activity is downregulated in some AD patients, and this could lead to an enrichment in hexadecyl-containing precursor lipids (33, 34). Moreover, LPCAT1 and LPCAT2 preferentially use 18:2- and 18:3-CoA (LPCAT1) or 20:4-CoA (LPCAT2) over acetyl substrates (35) and thus are more likely to regenerate structural membrane lipids than produce PAF second messengers under physiological conditions. We show here that, in the absence of Aβ42, hNT neurons preferentially convert internalized lyso-PAF to alkylacylglycerophosphocholines as expected, while in the presence of Aβ42, C16:0 PAF accumulation is favored. Thus, it is likely that exposure to pathogenic concentrations of Aβ42 alters LPCAT substrate preference toward acetyl-CoA generating PAF.

With respect to underlying signaling mechanisms, we show that rising intraneuronal concentrations of C16:0 PAF in response to Aβ42 target the ER to sequentially activate m-calpain, Cdk5, and GSK3β, leading to AT8-reactive phosphorylation of human tau. While PAFs have previously been shown to activate GSK3β (27), our data demonstrate that alkylacylglycerophosphocholine metabolites can also signal through Cdk5. Pharmacological inhibition of Cdk5 prevented both C16:0 PAF-induced tau phosphorylation and C16:0 PAF-induced caspase-dependent neuronal apoptosis, indicating that this kinase is likely the primary effecter. Both pharmacological intervention with orsellinic acid, a PAF inhibitor that targets the PAF-induced ER caspase pathway (31) and molecular gain-of-function approaches to enhance hydrolysis of C16:0 PAF to C16:0 lyso-PAF were sufficient to inhibit Aβ42 neurotoxicity, providing further evidence that these pathways can be potentially modulated in AD. Collectively, these data provide insight into how disruption of glycerophosphocholine metabolism can define neuronal response to accumulating oligomeric Aβ42 identifying potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Tissue.

Flash-frozen parahippocampal gyri without fixation from deceased AD patients (74 ± 8 years) and controls (78 ± 16 years) who suffered sudden death due to non-neurological complications were obtained from the Douglas Hospital Research Centre Brain Bank (Montreal, Canada). Postmortem delay was between 5 and 25 h. TgCRND8 mice (13) and NonTg littermate controls were killed at 8 or 14–16 weeks of age. All animal manipulations were performed according to the strict ethical guidelines for experimentation established by the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

Lipid Analysis.

Glycerophospholipids were extracted according to a modified Bligh and Dyer procedure (16). LC-ESI-MS and TLC analyses were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Neuronal Culture and Assays.

NT2/D1 cells were terminally differentiated to hNT neurons as described in ref. 36. RT-PCR conditions and primer sequences were as described in ref. 16. All treatment details are detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Transfections, quantification, calcium imaging methodologies, activity assays, and antibodies used for Western analyses are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation (OMHF), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) MOP-89999 (to S.A.L.B., D.F.), CIHR and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (HSFO) (D.S.P.), CIHR MOP-84527, Alzheimer Society of Ontario (to P.E.F.), and the CIHR Training Program in Neurodegenerative Lipidomics (TGF-96121) (to S.A.L.B., D.F., D.S.P., P.E.F.). S.D.R., A.J.G.B., A.P.B., and T.C.M. were OMHF, Ontario Genomics Institute, and Alzheimer Society of Canada scholars. S.N.W. and L.A.S. were Heart and Stroke Foundation, Centre for Stroke Recovery, and Vision 2010 postdoctoral fellows. D.S.P. is a HSFO career investigator. We thank Dr. Sheng Hou, National Research Council, for assistance with calcium imaging, Jim Bennett for editorial assistance, and Mark Akins for outstanding technical support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905654106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierer LM, et al. Neocortical neurofibrillary tangles correlate with dementia severity in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:81–88. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540250089017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Mejia RO, et al. Phospholipase A(2) reduction ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1311–1318. doi: 10.1038/nn.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kriem B, et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 mediates neuronal apoptosis induced by soluble oligomers of the amyloid-beta peptide. FASEB J. 2005;19:85–87. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1807fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kita Y, Ohto T, Uozumi N, Shimizu T. Biochemical properties and pathophysiological roles of cytosolic phospholipase A2s. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1317–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firuzi O, Zhuo J, Chinnici CM, Wisniewski T, Pratico D. 5-Lipoxygenase gene disruption reduces amyloid-beta pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2008;22:1169–1178. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9131.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein J. Membrane breakdown in acute and chronic neurodegeneration: Focus on choline-containing phospholipids. J Neural Transm. 2000;107:1027–1063. doi: 10.1007/s007020070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweet RA, et al. Psychosis in Alzheimer disease: Postmortem magnetic resonance spectroscopy evidence of excess neuronal and membrane phospholipid pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:547–553. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross BM, Moszczynska A, Erlich J, Kish SJ. Phospholipid-metabolizing enzymes in Alzheimer's disease: Increased lysophospholipid acyltransferase activity and decreased phospholipase A2 activity. J Neurochem. 1998;70:786–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shindou H, et al. A single enzyme catalyzes both platelet-activating factor production and membrane biogenesis of inflammatory cells. Cloning and characterization of acetyl-CoA:LYSO-PAF acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6532–6539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harayama T, Shindou H, Ogasawara R, Suwabe A, Shimizu T. Identification of a novel noninflammatory biosynthetic pathway of platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11097–11106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead SN, et al. Rapid identification and quantitation of changes in the platelet activating factor family of glycerophospholipids over the course of neuronal differentiation by high performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8359–8548. doi: 10.1021/ac0712291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chishti MA, et al. Early-onset amyloid deposition and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice expressing a double mutant form of amyloid precursor protein 695. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21562–21570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100710200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: Globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bae K, et al. Platelet-activating factor (PAF)-dependent transacetylase and its relationship with PAF acetylhydrolases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26704–26709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonin F, et al. Anti-apoptotic actions of the platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase I alpha 2 catalytic subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52425–52436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410967200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manya H, et al. Switching of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase catalytic subunits in developing rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18567–18572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratton DL. Release of platelet activation factor from activated neutrophils. Transglutaminase-dependent enhancement of transbilayer movement across the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3364–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaughlin NJ, et al. Platelet-activating factor-induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis requires beta-arrestin-1 recruitment and activation of the p38 MAPK signalosome at the plasma membrane for actin bundle formation. J Immunol. 2006;176:7039–7050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song S, et al. E2–25K/Hip-2 regulates caspase-12 in ER stress-mediated Abeta neurotoxicity. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:675–684. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer H, Koenig U, Eckhart L, Tschachler E. Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:722–726. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahmer MK. Caspases-2, -3, and -7 are involved in thapsigargin-induced apoptosis of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:576–583. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meary F, et al. A mutant alphaII-spectrin designed to resist calpain and caspase cleavage questions the functional importance of this process in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14226–14237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon S, Choi J, Huh JW, Hwang O, Kim D. Calpain activation in okadaic-acid-induced neurodegeneration. Neuroreport. 2006;17:689–692. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000214398.04093.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MS, et al. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405:360–364. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goni-Oliver P, Lucas JJ, Avila J, Hernandez F. N-terminal cleavage of GSK-3 by calpain: A new form of GSK-3 regulation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22406–22413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong N, et al. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3beta) by platelet activating factor mediates migration and cell death in cerebellar granule neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1913–1922. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraf MK, Kishore K, Thomas KM, Sharma A, Singh M. Role of platelet activating factor in triazolobenzodiazepines-induced retrograde amnesia. Behav Brain Res. 2003;142:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izquierdo I, et al. Memory enhancement by intrahippocampal, intraamygdala, or intraentorhinal infusion of platelet-activating factor measured in an inhibitory avoidance task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5047–5051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan SD, et al. Platelet activating factor-induced neuronal apoptosis is initiated independently of its G-protein coupled PAF receptor and is inhibited by the benzoate orsellinic acid. J Neurochem. 2007;103:88–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igbavboa U, Hamilton J, Kim HY, Sun GY, Wood WG. A new role for apolipoprotein E: Modulating transport of polyunsaturated phospholipid molecular species in synaptic plasma membranes. J Neurochem. 2002;80:255–261. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan W, et al. The highly selective production of 2-arachidonoyl lysophosphatidylcholine catalyzed by purified calcium-independent phospholipase A2gamma: Identification of a novel enzymatic mediator for the generation of a key branch point intermediate in eicosanoid signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26669–26679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talbot K, et al. A frontal variant of Alzheimer's disease exhibits decreased calcium-independent phospholipase A2 activity in the prefrontal cortex. Neurochem Int. 2000;37:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shindou H, Shimizu T. Acyl-CoA: Lysophospholipid acyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boucher S, Bennett SAL. Differential connexin expression, gap junction intercellular coupling, and hemichannel formation in NT2/D1 human neural progenitors and terminally differentiated hNT neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:393–404. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.