Abstract

Background

Recent European Union regulation requires setting of maximum amount of micronutrients in dietary supplements or foods taking into account the tolerable upper intake level (ULs) established by scientific risk assessment and population reference intakes.

Objective

To collect and evaluate recently available data on intakes of selected vitamins and minerals from conventional foods, food supplements and fortified foods in adults and children. Intake of calcium, copper, iodine, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, selenium, zinc, folic acid, niacin and total vitamin A/retinol, B6, D and E was derived from nationally representative surveys in Denmark, Germany, Finland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom. Intake of high consumers, defined as the 95th percentile of each nutrient, was compared to the UL.

Results

For most nutrients, adults and children generally consume considerably less than the UL with exceptions being retinol, zinc, iodine, copper and magnesium. The major contributor to intakes for all nutrients and in all countries is from foods in the base diet. The patterns of food supplements and voluntary fortification vary widely among countries with food supplements being responsible for the largest differences in total intakes. In the present study, for those countries with data on fortified foods, fortified foods do not significantly contribute to higher intakes for any nutrient. Total nutrient intake expressed as percentage of the UL is generally higher in children than in adults.

Conclusion

The risk of excessive intakes is relatively low for the majority of nutrients with a few exceptions. Children are the most vulnerable group as they are more likely to exhibit high intakes relative to the UL. There is a need to develop improved methods for estimating intakes of micronutrients from fortified foods and food supplements in future dietary surveys.

Keywords: micronutrients, EU legislation, upper safe levels, adults, children

Recent European Union (EU) legislation has provided for the harmonisation of regulations on the vitamin and mineral content of food supplements and fortified foods. Both Directive 2002/46/EC on food supplements (1) and Regulation 1925/2006 on the addition of vitamins and minerals (2) and of certain other substances to foods provide, among other aspects, the setting of maximum amounts of vitamins and minerals in these products via the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health and lay down the criteria for their setting.

The EU regulation on the addition of nutrients to foods recognises that low intakes and even deficiencies exist for some micronutrients within the European population, and that fortification has an important role in addressing such nutritional imbalances. However, the main criterion for setting maximum levels will be safety rather than low intakes. Therefore, the current paper seeks to focus mainly on intakes at this end of the intake spectrum. Prior to the enactment of the EU Regulation on addition of nutrients to foods, national regulations on food fortification varied considerably throughout the EU. This is important to bear in mind when interpreting the national data presented in this paper.

Under the new regulation, maximum amount of a micronutrient in dietary supplements or foods will be set taking into account the upper safe levels established by scientific risk assessment and population reference intakes. For foods, the maximum amount of a micronutrient added will also take into account intakes from other dietary sources and the contribution of individual food categories to the overall diet or to the intakes of particular population sub-groups. Because the considerations for setting maximum levels for both foods and food supplements are interrelated, these will be set together.

Tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) of vitamins and minerals have been reviewed for the EU by the European Community (EC) Scientific Committee on Food (SCF) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 3). In those scientific opinions, specific UL values have been established for 16 of the 34 nutrients reviewed. For the remaining nutrients, ULs were not established for various reasons, including evidence of no adverse effect, lack of evidence for any adverse effect or insufficient data to establish dose–response relationships for established adverse effect.

A number of scientific bodies and stakeholders have considered possible approaches to the setting of maximum levels and several models have been proposed (4–10).

Most rely on approximations of current intakes from conventional foods, food supplements and fortification (where practised), with conservative assumptions and additional safety factors to minimise the risk of excess intakes in population groups, and thus are likely to under estimate the maximum safe level for many nutrients. It is therefore necessary to have a better understanding of current dietary intakes, including the contribution of conventional foods, food supplements and fortification (where practised). Dietary data on intakes of vitamins and minerals in different population groups are not available for many EU Member States and where they do exist they are often limited, particularly with respect to intakes from fortified foods and food supplements.

The objective of this paper is to provide a better understanding of the risks of excess intake in representative European countries, by collating and evaluating the most recently available data from nationally representative surveys on intakes of vitamins and minerals in adults and children. Where possible, the separate contributions of conventional foods, food supplements and fortified foods have been collected.

Data are presented for selected nutrients, focusing mainly on those vitamins and essential minerals for which adverse effects have been reported in humans and which are most likely to be added to both food supplements and fortified foods.

Collection and analysis of nutrient intake data

Dietary survey methodologies

Food consumption data were derived from recently available, nationally representative food consumption surveys of selected European countries that volunteered for this exercise (see Table 1). The differences in methodology used in the different surveys are discussed as follows.

Table 1.

Dietary survey methods used for the present study

| Country | Year | Methodology used | N | Age range, ys | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 2000–2004 | Seven-day pre-coded record | 5,885 | 4–75 | (11) |

| Finland | 2002 | 48-h recall + survey on use of fortified foods, for distribution modelling: Monte Carlo simulation (fortification) and C-SIDE® | 2,007 | 25–64 | (12) |

| Germany | 1997–1999 | Modified diet history | 4,030 | 18–79 | (13–16) |

| 2006 | Modified diet history (12–17 ys) three-day estimated food diary (6–11 ys) | 2,506 | 6–17 | ||

| Ireland | 1997–1999 | Seven-day estimated food diary | 1,379 | 18–64 | (17, 18) |

| 2003–2004 | Seven-day weighed food diary | 594 | 5–12 | ||

| Italy | 1994–1996 | Seven-day record (non-pre-coded food) | 1,200 households 2,700 individuals analysed 1,978 individuals (manually checked bad-reporters were excluded) | 0–94 | (19) |

| The Netherlands | Young adults 2003 | Two 24-h recall on non-consecutive days | 750 | 19–30 | (20, 21) |

| Total population 1997/1998 | Food record on two consecutive days | 5,958 | 1–95 | (22) | |

| Young children 2005/2006 | Two diet records on non-consecutive days | 639 | 4–6 | (23) | |

| Poland | 2000 (September–December) | 24-h recall | 4,134 | 1–96 | (24) |

| Spain | Adults: 2002–2003 | Two 24-h recall on non-consecutive days and a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire | 2,160 | 10–80 | (25, 26) |

| 1,613 | 18–64 | ||||

| Children: 1998–2000 | One 24-h recall (a second one in one-third of the sample on a non-consecutive day) | 3,534 | 2–24 | ||

| 1,860 | 4–17 | ||||

| United Kingdom | 1997 | Face-to-face interview; seven-day food and supplements diary and seven-day weighed intake | 2,127 | 4–18 | (27) |

| 2000–2001 | 2,251 | 19–64 | (28) |

Some of these differences in survey design are unavoidable and appropriate since local situations may differ (e.g. a stratification by federal state like Germany would not make sense in the Netherlands). Four countries used a seven-day food diary, four a short recall (one or two day 24-h recalls) and one a modified diet history with a reference period of four weeks as the major dietary assessment method. Except for the Dutch young adults and the Polish survey, the surveys covered all seasons of the year. Age ranges for children and adolescents are very similar for the different countries, but for adults they are more varying. The Dutch young adult survey only covers the 19–30 aged population, but since this is a very recent survey and is one of the few which has assessed the contribution of conventional diet, supplements and fortified foods separately we wanted to include it.

Food intake information is analysed by combination with national food composition data. The national food composition databases are compiled variously from direct analyses of foods, from published or unpublished sources and by calculations or imputation of data from similar foods. Some discrepancies between food composition from different countries may occur because some countries apply retention factors to the composition of raw foods, whereas other countries (e.g. Italy) don't. The latter situation may lead to an overestimation of micronutrient intake.

Only the Danish survey was based on a total random sample. For practical, logistical and statistical efficiency reasons, all others used some kind of clustering (for regions, communities, schools or households) and stratification (like for region, community size, sex, age, social class) before random samples were drawn. The differences in sampling design partially reflect organisational or geographical structures in the countries.

Pregnant or lactating women were excluded in Ireland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Several surveys were analysed using a calculated weighting factor to correct for differences between the structure of the survey samples and the actual population (e.g. age, community size) in order to improve representativeness. This was the case for Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Some surveys were connected with, or sub-samples of, other studies. For example, the German Nutrition Survey is part of a national health survey.

Finally, the different surveys are affected by varying degrees of underreporting which can be identified by the proportions of persons with low ratios of energy intakes and predicted metabolic rate. However, we decided not to exclude low energy reporters, as the main focus of this report is on intakes at the upper end of the intake distribution. Energy underreporting is less likely to affect the higher end of the intake distribution than the lower end. Energy overreporting might have an impact on the upper end of the intake distribution; however, the prevalence of overreporting is generally low (30).

Selection of nutrients

The context of this work was the estimation of maximum safe levels of micronutrients in fortified foods and food supplements. Therefore, the nutrients selected were those which are likely to be used for food fortification; and those with a relatively low UL in comparison with normal or recommended intakes.

Based on these criteria, the following nutrients were selected for detailed analysis and evaluation: the minerals calcium, copper, iodine, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, selenium, zinc; and the vitamins folic acid, niacin (nicotinamide), A/retinol, B6, D and E.

Data analysis

The main focus of the data analysis was on comparing intakes for nutrients with European values for tolerable UL. For this the habitual intake of the population is most relevant. Therefore, intake distributions from surveys with short reference periods (Finland, the Netherlands and Spain) were remodelled to estimate the usual intake distributions using information of intra individual (within-person) variation as described in literature (21, 29, 31), with special statistical software (e.g. C-SiDE) (29). Surveys with a reference period of seven days or more were assumed to reflect the usual intake sufficiently well (32).

To facilitate comparison of intakes across countries, almost all data were remodelled to fit standard age ranges of children 4–10 ys, children 11–17 ys (exceptions Ireland 5–10, the Netherlands 4-6 ys, Germany 12–17 ys), adult men and adult women (exception the Netherlands 19–30 ys). These correspond to ranges used by the EFSA and the SCF in setting tolerable ULs for foods and food supplements (3).

Children were grouped into two larger age ranges, rather than the four used by the SCF in order to increase the statistical power of the data for countries with relatively small sample sizes.

For all surveys the 5th, 50th, 95th percentiles (P5, P50, P95) as well as the arithmetic mean intakes of selected nutrients were calculated for the base diet (including non-fortified and mandatorily fortified foods), base diet plus supplements and base diet plus supplement plus fortified foods.

Mandatory fortification is included in the definition of base diet because in most countries this practice is either required by statute or officially encouraged in order to maintain availability of key nutrients. For example, where a new food partially replaces the existing food which is a main source of an important nutrient. Margarine is mandatorily restored with vitamins A and D in most countries as a partial replacement for butter, which is a dietary source of both vitamins. Therefore, foods fortified under these circumstances are essentially dietary equivalents of traditional foods, and not subject to the regulation of voluntarily fortified foods, which is the context of the current paper.

‘Base Diet plus Supplements’ is intended to be an estimate of the incremental affect of supplement consumption by general population, over and above traditional diets. The third category including voluntarily fortified foods in addition to base diet and supplements, helps elucidate the combined effect of both practices on intakes in the general population sub-groups defined.

For those countries which could estimate nutrient intakes separately from supplements or fortified foods, these distributions were calculated. However where the data includes many zero values, which is the case for supplement use, the latter distributions could not be calculated for surveys estimating usual intake by statistical modelling, due to transformation problems.

For the interpretation of the results, a decision was taken to use the P95 intakes, which were compared to the tolerable ULs as defined by the EFSA (3). The P95 intake level was chosen versus higher cut-offs such as P97.5 because, available data were mainly obtained from dietary surveys with a relatively short reference period and for some age groups the samples were relatively small. This makes the estimation of the tails of the distribution less stable. Under such conditions, the P95 values provide a more robust estimate of habitual intake for high consumers than higher percentiles. This means that for nutrients with intake levels near to the UL, a small proportion of the population (but maybe larger than in evaluations using the P97.5) may still exceed the UL. This should be kept in mind in a final evaluation and could be adjusted for by using somewhat larger uncertainty factors.

Supplement use

Only about half of the countries could include the separate contribution of supplement use to the intake of some nutrients, and even fewer had information on consumption of fortified foods. Therefore, a possible underestimation of particular nutrient intakes from these sources has to be considered.

Information on dietary supplement use was assessed in various ways. See Tables 2 and 3. There are variations in the definition of supplements, the reference period on which information was obtained and the level of detail. With the exception of Denmark where a generic supplement (nutrient content based on weighed amounts of nutrients according to household purchase) was formed, nutrient intakes from supplements were calculated using national tables on micronutrient contents of dietary supplements. These databases were mostly compiled using information obtained from the label, the internet or producers, rather than direct analyses of supplements.

Table 2.

Summary of methodology for supplement intake

| Country | Year | Age (ys) | Reference period | Specification | Supplement composition database |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 2000–2002 | 4–75 | 12 months | Generic typea | Study specific database |

| Finland | 2002 | 25–64 | Six months | Specific description | National database |

| Germany | 1997–1999 | 18–79 | 12 months | Specific description | Study specific database |

| 2006 | 6–11 | Three days | Specific description | Study specific database | |

| 2006 | 12–17 | Four weeks | Specific description | Study specific database | |

| Ireland | 2003–2004 | 5–12 | Seven days | Specific description | Label information during interview |

| 1997–1999 | 18–64 | Seven days | Specific description | Label information during interview | |

| Italy | 1994–1996 | 0–94 | Survey period | Generic type | |

| The Netherlands | 2005–2006 | 4–6 | Two days | Specific description | National database |

| 2003 | 19–30 | Two days | Specific description | National database | |

| Poland | 2000 | 1–96 | One day | (Mostly) generic type | Study specific database |

| Spain | 1998–2000 | 4–17 | 12 months | Generic type | Study specific database |

| 2002–2003 | 18–64 | 12 months | Generic type | Study specific database | |

| United Kingdom | 2000–2001 | 19–64 | Seven days | Specific description | Study specific database |

aThis information was combined with market share data on specific brands from Danish consumer scan data.

Table 3.

Percentage of dietary supplements users in various food consumption surveys (%)

| Country | Reference period | Age (ys) | Percentage (%) of men | Percentage (%) of women |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 12 months | 4–75 | 54 | 60 |

| Finland | Six months | 25–64 | 32 | 58 |

| Germany | 12 months | 18–79 | 38 | 48 |

| Three days | 6–11 | 8 | 9 | |

| Four weeks | 12–17 | 20 | 20 | |

| Ireland | Seven days | 5–12 | 27 | 22 |

| Seven days | 18–64 | 16 | 31 | |

| Poland | One day | 1–96 | 11 | 18 |

| The Netherlands | Two days | 4–6 | 31 | 28 |

| Two days | 19–30 | 21 | 33 | |

| Spaina | 12 months | 4–17 | 15 | 18 |

| 12 months | 18–64 | 8 | 10 | |

| United Kingdoma | Seven days | 19–64 | 29 | 40 |

aDid not have available data on nutrient intake of supplements.

For most surveys, the reference period was the same as for the dietary assessment. Exceptions are Denmark, Germany and Spain which had a 12-month reference period for supplement use and Finland who had a six-month reference period for supplement use as well as for consumption of fortified foods.

Fortification practices

Some countries (Finland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom) are able to provide separate data on the contribution to nutrient intake of fortified foods. Intakes were generally assessed by asking for brand names for particular food groups, within the dietary assessment method. Nutrient contents of these products were gathered from package information, company information, etc. Therefore, since these sources do not differentiate between added and naturally occurring amounts, the contribution from a given food normally reflects the total nutrient content of the fortified food, and not the amount added during fortification.

In the case of foods which are mandatorily fortified, or by officially encouraged practice (like vitamin D in fat spreads and iodine in salt), these were included in the base diet data.

An understanding of actual fortification practices in the specific countries is important background for the proper interpretation of the analyses presented here. Table 4 describes the national practices of mandatory and voluntary fortification at the time of the dietary surveys used in this study.

Table 4.

Fortification practices in Europe prior to 2006

| Country | Fortification practice |

|---|---|

| Denmark |

|

| Finland |

|

| Germany |

|

| Ireland |

|

| Italy |

|

| The Netherlands |

|

| Poland |

|

| Spain |

|

| United Kingdom |

|

In many of the participating countries, voluntary fortification was permitted for all foods for general consumption, including Finland, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom.

The level of nutrients added in some of these countries was governed by the general regulations covering food safety, as in the United Kingdom and Ireland, whilst others required notification such as in Poland and Denmark. In Germany, all water-soluble vitamins were allowed without prescribed limit, whilst vitamin A and D were restricted to certain foods like margarine and only at permitted and specified levels. In the Netherlands, vitamin D, retinol, folic acid, selenium, copper and zinc were forbidden, unless authorised for specific foods. In other countries, notably in Scandinavia, voluntary fortification was restricted to specific levels of certain nutrients in specific foods.

Results

Comparison of intakes

The intakes of each of the selected nutrients are provided in tabular form in the Appendix. The data are presented by nutrient in each country for P5, P50 and P95 intakes. Intakes are given separately for children 4–10 ys, 11–17 ys, adult men and adult women, and thus refer to the total population (users and non-users).

Where available, intakes are given separately for base diet only (including mandatory fortified foods), base diet plus supplements and base diet plus supplements and fortified foods.

In addition, the data have been provided in graphical format, to facilitate direct comparison of intakes between countries.

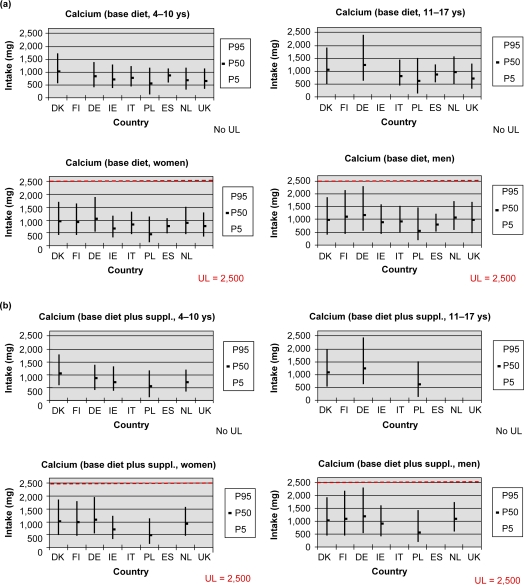

Calcium

Upper intake level (UL) for calcium

The UL for calcium for adults was derived on the basis of the abundant evidence of absence of adverse effects in intervention studies of long duration in adults, in which total daily calcium intakes of 2,500 mg from both diet and supplements were consumed (3). No UL has been established for children and adolescents. Although available data showed no adverse effects of additional calcium intake up to 1,000 mg/d from foods or supplements (in addition to usual diet) over 1–3 ys in children between six and 14 ys of age, the available data were considered insufficient to establish an UL. It was also considered inappropriate to derive an UL for calcium for this age group by adjustment of the adult UL for body size because of uncertainty regarding the relationship of increased calcium deposition rate during growth to body size (3).

Calcium intake – Adults

The P95 intake of calcium from base diet ranged from 1,203 mg/d (Spain) to 2,263 mg/d (Germany) in men and 1,045 mg/d (Spain) to 1,860 mg/d (Germany) in women (Fig. 1a and b). These intakes were below the UL also when supplements and voluntary fortification were included. For the base diet, the P95 intake of calcium as % UL ranged from 48 to 91% in men and 45–74% in women. Higher intakes of calcium from the base diet are associated with high consumption of milk and dairy products.

Fig. 1.

(a) Calcium intake from the base diet. (b) Calcium intake from the base diet plus supplements.

While the P95 intake of calcium from supplements alone ranged up to 500 mg (data not presented), inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in a relatively small increase in P95 intake. This indicates that P95 intakes of calcium from supplements is not additive with P95 from base diet and that high consumers of calcium from supplements are generally not high consumers of calcium from the base diet.

The P95 intake of calcium from voluntarily fortified foods was low and inclusion of intake from voluntarily fortified foods with that from the base diet and supplements had little effect on P95 intake. This may be because some fortified foods are natural sources of calcium which replace other (non-fortified) natural sources e.g. dairy products. In this regard, it is important to note that the contribution of calcium-fortified foods is less than the contribution of ‘fortified foods’ (which are fortified but not necessarily with calcium, e.g. vitamin D fortified dairy products). Addition of calcium to foods is limited by technological considerations, e.g. taste, solubility (10).

Calcium intake – Children

For children, the P95 of calcium intake from base diet ranged from 1,100 to 1,700 mg/d and 1,200 to 2,400 mg/d in the age groups of 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively. Higher intakes were associated with higher consumption of milk and dairy products. The limited data available on intakes of calcium from supplements and fortified foods for these age groups indicate that intake from these sources is low and that inclusion of these sources with base diet has only a minimal effect on P95 intake.

In Ireland, about 30% of fortified foods consumed by children contain added calcium and the median level of calcium (indigenous and added) in an average serving of fortified food was about 180 mg (22% of EC Recommended Daily Amounts (RDA)) (P25 13%, P75 27%) (31). This compares with a calcium content of about 240 mg in a glass (200 ml) of milk. The mean percentage of energy intake consumed as foods fortified with one or more nutrients is about 9% for children and 3% for adults; for foods fortified with calcium this is below 3% in children and below 1% in adults (33, 34). Unfortunately, this information is not available for other countries.

Comment

Total intakes of calcium vary considerably between countries but are below the UL even in high consumers. High intakes of calcium are mainly associated with high consumption of milk and dairy products and not with use of supplements or fortified foods.

Patterns of consumption of calcium containing supplements and fortified foods appear to be unlikely to lead to excessive calcium intakes overall. For example, high consumers of calcium from supplements are generally not high consumers of calcium from the base diet and intakes of calcium from fortified foods may replace, rather than add to, intakes of calcium from non-fortified natural sources of calcium. In addition, the levels of added calcium in foods appear to be modest so that total calcium content of the foods is nutritionally significant but not excessive.

These findings suggest that models for estimating maximum safe levels of addition of nutrients to foods and supplements may be conservative for calcium because they do not take into account likely patterns of consumption. Furthermore, based on current practise in Ireland, the proportion of food energy likely to be fortified with calcium may be much lower than for some micronutrients and the risk assessment models should take this into account.

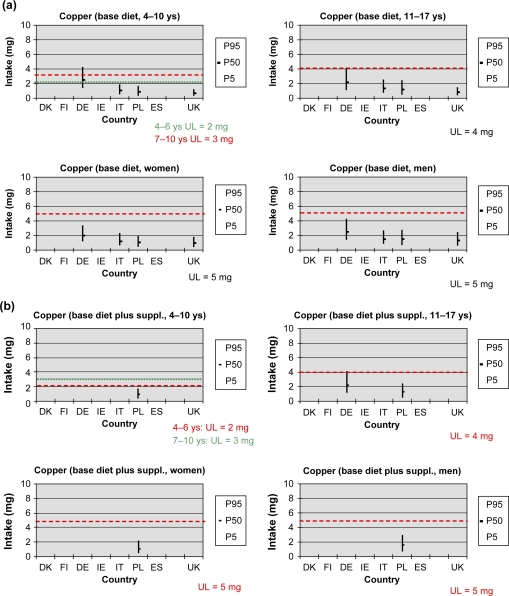

Copper

Upper intake level (UL) for copper

The UL for copper for adults of 5 mg/d was derived on the basis of the evidence of absence of adverse effects on liver function in intervention studies in adults. The UL is not applicable during pregnancy or lactation. ULs for children were derived by adjusting the adult UL for differences in body weight. For children 4–6, 7–10 and 11–17 ys of age the UL for copper is 2, 3 and 4 mg/d, respectively (3).

Copper intake – Adults

P95 of intake of copper from base diet in men ranged from 2.4 mg/d (United Kingdom) to 4.2 mg/d (Germany) and in women from 1.7 mg/d (United Kingdom) to 3.3 mg/d (Germany) from the base diet. This was less than the UL, i.e. 48–84% in men and 34–66% in women for four of the five countries for which data were available.

Copper intake from fortified foods was very low. Few data are available on copper intake from supplements or fortified foods in European countries (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

(a) Copper intake from the base diet. (b) Copper intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Copper intake – Children

For children aged 6–11 ys in Germany, the P95 of copper intake exceeded the UL for 7–10 ys olds, ie. 3mg/d. From the few data available it appears that there is little contribution from supplements or fortified foods in children.

Comment

The UL that has been established for copper is low relative to the observed intakes and P95 intakes from base diet exceeded the UL in adults and children by small amounts in some countries. Based on data for only a few countries, the contribution of supplements to P95 intake was low. Copper intake from voluntarily fortified foods is low and copper is added to foods only infrequently (33). There are no reported adverse health effects associated with the small proportions of children exceeding UL for copper and the SCF has indicated that the observed copper intakes close to the UL in EU are not a matter of concern (3).

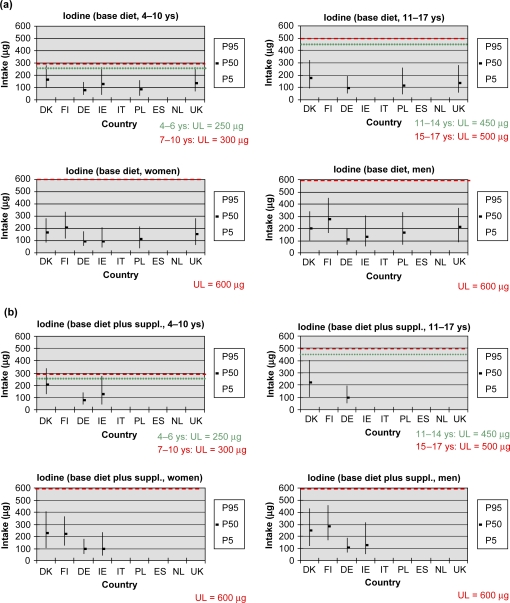

Iodine

Upper intake level (UL) for iodine

The UL for iodine for adults was set at 600 µg/d (3). This was derived on the basis of the study covering five-year exposure at approximately similar iodine intake levels of 30 µg/kg body weight/d (equivalent to approximately 1,800 µg iodide/d) in which no clinical thyroid pathology occurred, using an uncertainty factor of 3. The UL of 600 µg is also considered to be acceptable for pregnant and lactating women based on evidence of lack of adverse effects at exposures significantly in excess of this level.

Since there is no evidence of increased susceptibility in children, the ULs for children were derived by adjustment of the adult UL on the basis of body surface area. For children 4–6, 7–10, 11–14, 15–17 ys of age, the UL for iodine is 250, 300, 450, 500 µg/d, respectively (3).

The SCF notes that an UL is not a threshold of toxicity but may be exceeded for short periods without an appreciable risk to the health of the individuals concerned (3).

These ULs do not apply to Iodine Deficiency Disorder populations, as these are more sensitive to iodine exposure (3).

Iodine intake – Adults

The P95 intake of iodine in men and women was less than the UL for base diet and when supplements and voluntary fortification were included.

The P95 intake of iodine from base diet ranged from 190 µg/d (Germany) to 447 µg/d (Finland) in men and from 171 µg/d (Germany) to 334 µg/d (Finland) in women, respectively.

For the base diet, the P95 intake of iodine as % UL ranged from 32% (Germany) to 75% (Finland) in men and from 29% (Germany) to 56% (Finland) in women. Higher intakes of iodine from the base diet are associated with high consumption of milk and dairy products, bread, marine fish and iodised salt. Iodine from the latter is included in the values from the base diet (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

(a) Iodine intake from the base diet. (b) Iodine intake from the base diet plus supplements.

The P95 intake of iodine from supplements alone ranged up to 156 µg/d in men and women (Denmark) (data not included). Inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in an increase in P95 intake, but did not exceed UL (Fig. 3b).

The P95 intake of iodine from voluntarily fortified foods is low and inclusion of intake from voluntarily fortified foods with that from the base diet and supplements had little effect on P95 intake.

Iodine intake – Children

For children, the P95 of iodine intake from base diet ranged from 140 µg/d (Germany) to 280 µg/d (Denmark) in the age group 4–10 and 189 µg/d (Germany) to 324 µg/d (Denmark) in the age group 11–17.

For children aged 4–10 ys, the P95 intake of iodine from base diet exceeded 250 µg/d (UL for children in the age group 4–6) by a small amount, but was less than 300 µg/d (UL for children in age group 7–10) in Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Inclusion of supplements increased the P95 intake of iodine in Denmark to over 300 µg/d, but had little effect on P95 intakes in Ireland. Inclusion of voluntarily fortified foods for Ireland and United Kingdom had little effect on the P95 intake.

For children aged 11–17 ys, the P95 intake of iodine from base diet (including mandatorily fortified foods), base diet plus supplements, base diet plus supplements plus fortified foods was less than UL. Inclusion of supplements with base diet increased the P95 intake of iodine in Denmark to about 400 µg/d (Fig. 3a and b).

The data on intake of iodine from supplements (alone) and from voluntarily fortified foods for these age groups are limited.

Comment

The P95 of total intake of iodine (including supplements and voluntary fortification) in adults does not exceed the UL. P95 intakes of iodine from base diet vary considerably between countries, mainly due to different intakes from consumption of milk and dairy products, bread, marine fish and iodised salt. Iodine from the latter is included in the values from the base diet.

For 4–10-year-old children (but not in 11–17-year-old children), P95 of intake from base diet approaches the UL in some countries and, when supplements are included, P95 intake exceeds the UL in Denmark.

The limited available data on intake from fortified foods indicate that intake of iodine from voluntarily fortified foods is low and has little effect on the P95 intake of total diet. It appears that iodine is added to foods only infrequently (33, 34).

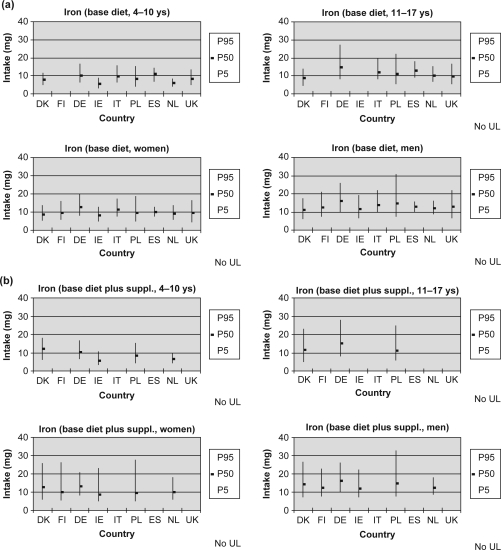

Iron

Upper intake level (UL) for iron

No UL has been established for iron because the available data were considered insufficient (3). Reported associations between high iron intake and/or stores with increased risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, Type II diabetes and cancer of the gastrointestinal tract do not provide convincing evidence of a causal relationship between iron intake or stores and such chronic diseases. While a proportion of the population has serum ferritin levels indicative of elevated iron stores, the risk of adverse effects from iron overload (such as liver fibrosis) in the general population, including those heterozygous for hereditary haemochromatosis, is considered to be low. However, intake of iron from food supplements in men and postmenopausal women may increase the proportion of the population likely to develop biochemical indicators of high iron stores. Adverse gastrointestinal effects (e.g. nausea, epigastric discomfort, constipation) have been reported after short-term oral dosage at 50–60 mg daily of supplemental non-haem iron preparations, particularly if taken without food, and a Guidance Level of 17 mg for supplements only has been established in the United Kingdom (34) based on the adverse gastrointestinal effects of supplemental non-haem iron.

Iron intake – Adults

The P95 intake of iron from base diet ranged from 16 mg/d (Spain) to 31 mg/d (Poland) in men and from 13 mg/d (Ireland) to 20 mg/d (Germany) in women, respectively. Higher intakes of iron from the base diet are associated with high consumption of cereals (non-haem) and meat products (haem) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

(a) Iron intake from the base diet. (b) Iron intake from the base diet plus supplements.

The P95 intake of iron from supplements alone ranged up to 14 mg/d, and inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in an increase in P95 intake which was additive with P95 from base diet especially among women. In men, intake of iron from food supplements was generally low but P95 intake from supplements alone was 6 mg in the Netherlands and 12 mg in Denmark. The P95 intake of iron from voluntarily fortified foods is low and inclusion of intake from voluntarily fortified foods with that from the base diet and supplements had little effect on P95 intake.

Iron intake – Children

For children, the P95 of iron intake from base diet ranged from 8 to 16 mg/d and 14 to 27 mg/d in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively. The limited data available on intakes of iron from supplements for these age groups indicates that P95 of iron intake from supplements alone ranged up to 12 mg/d, and inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in an increase in P95 intake which was additive with P95 from base diet (Fig. 4a and b).

The limited data available on intakes of iron from fortified foods for these age groups indicate that in countries where voluntary fortification of foods is practised, P95 intake from this source can be up to about 5 mg/d and that inclusion of this source with base diet and supplements can increase P95 intake by this amount.

Comment

Based on these estimates of iron intakes in European countries, and in agreement with the SCF (3), the risk of adverse effects from high iron intake from food sources, including fortified foods in some countries, is considered to be low. The P95 intake of iron from supplements alone is lower than the United Kingdom Guidance Level; 17 mg (36), although some supplement users (women) can have intakes which exceed this level, at least over the short term (37). Intake of iron from food supplements in men was generally low, except for high consumers in some countries (e.g. P95 was 12 mg in Denmark and Finland – data not shown).

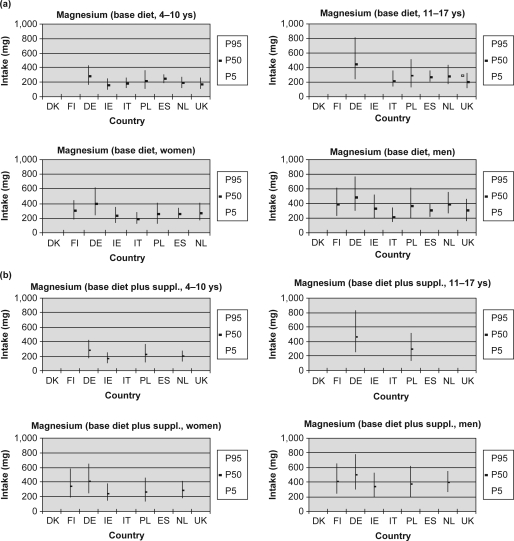

Magnesium

Upper intake level (UL) for magnesium

The UL for magnesium for adults was derived on the basis of the evidence from many observational studies about mild diarrhoea induced by daily oral magnesium supplements. This effect is without further pathological complications, is readily reversible and an adaptation may develop within days. The UL of 250 mg per day is only applicable to easily dissociable magnesium-salts or compounds like magnesium-oxide, which in practice means that it should be related to intake from supplements. The UL does not include magnesium normally present in foods and beverages. This UL is set for adults, including pregnant and lactating women and children of four ys and older. Due to unavailable data, no UL is set for children from one to three ys (3).

Magnesium intake – Adults

For the base diet, the P95 intake of magnesium ranged from 340 mg/d (Italy) to 750 mg/d (Germany) in men and from 260 mg/d (Spain) to 620 mg/d (Germany) in women. The P95 intake of magnesium from supplements alone ranged up to 250 mg/d referring to the whole population including non-consumers. The UL is only reached by the P95 supplemental intake of Finnish women. The inclusion of intake from supplements did not dramatically change the P95 intake from total diet. The P95 intake of magnesium from voluntarily fortified foods is low (up to 50 mg/d) and inclusion of intake has little effect on the P95 intake of the total diet (Fig. 5a and b).

Fig. 5.

(a) Magnesium intake from the base diet. (b) Magnesium intake from supplements.

Magnesium intake – Children

For children, the P95 of magnesium intake from the base diet ranged from 250 mg/d (Ireland) to 430 mg/d (Germany) and from 325 mg/d (United Kingdom) to 812 mg/d (Germany) in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively. The P95 of intake from supplements alone ranged up to 60 mg/d. The limited data available on intakes of magnesium from fortified foods indicate that intake from fortified foods is low and has only a minimal effect on the P95 intake of the total diet (Fig. 5a and b).

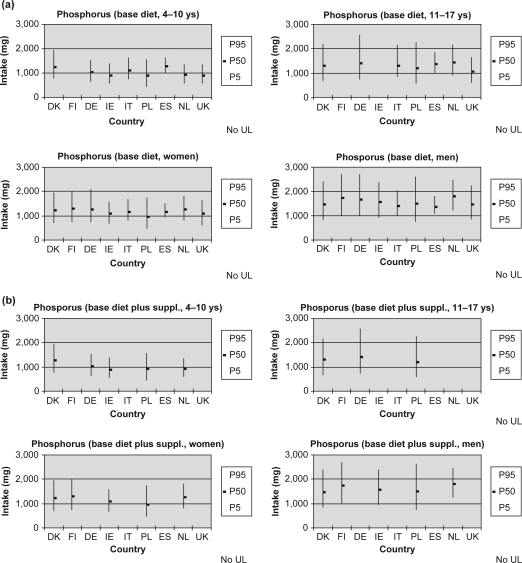

Phosphorus

Upper intake level (UL) for phosphorus

No UL has been established for phosphorus because the available data were considered insufficient (3). The available data indicate that normal healthy individuals can tolerate phosphorus (phosphate) intakes up to at least 3,000 mg phosphorus per day without adverse systemic effects. In some individuals, however, mild gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported if exposed to supplemental intakes >750 mg phosphorus per day. There is no evidence of adverse effects associated with the current dietary intakes of phosphorus in EU countries (3).

Phosphorus intake – Adults

The P95 intake of phosphorus from the base diet in men is from about 1,800 mg/d (Spain) to about 2,700 mg/d (Germany) and in women from about 1,500 mg/d (Spain) to about 2,100 mg/d (Germany). The intake of phosphorus from supplements was very low and had little effect on P95 intake from base diet (Fig. 6a and b).

Fig. 6.

(a) Phosphorus intake from the base diet. (b) Phosphorus intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Phosphorus intake – Children

In children aged 4–10 ys, the P95 of phosphorus intake from the base diet ranged from about 1,300 mg/d (United Kingdom) to about 1,900 mg/d (Denmark) (Fig. 6a) and in children and adolescents aged 11–17 ys from about 1,650 mg/d (United Kingdom) to about 2,570 mg/d (Germany).

The limited data available on intakes of phosphorus from supplements and fortified foods for these age groups indicate that intake from these sources are very low or not observed and that inclusion of these sources with base diet has little effect on P95 intake (Fig. 6b).

Comment

Base diet is the main source of dietary intake of phosphorus in adults and children and the intakes of phosphorus from supplements and fortified foods are low. Based on these estimates of phosphorus intakes in European countries, and in agreement with the SCF (3), the risk of adverse effects from high dietary intake phosphorus from foods, including fortified foods in some countries, and food supplements is considered to be low.

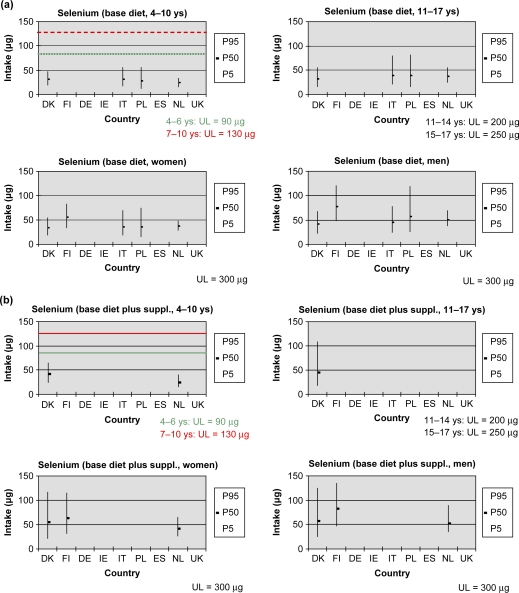

Selenium

Upper intake level (UL) for selenium

The UL of 300 µg selenium per day for adults was derived on the basis of evidence of absence of adverse effects of clinical selenosis in subjects exposed to varying dietary levels of selenium up to about 850 µg/d. UL for children were derived by adjusting the adult UL for differences in body weight. For children 4–6, 7–10, 11–14 and 15–17 ys of age, the UL for selenium is 90, 130, 200 and 250 µg/d, respectively (3).

This UL covers selenium intake from all sources of food including supplements. It relates to selenium naturally present in food, and those selenium compounds considered acceptable for use in food for particular nutritional uses, i.e. sodium selenate, sodium selenite and sodium hydrogen selenite.

Selenium intake – Adults

The P95 intake of selenium from base diet ranged from 68 mg/d (Denmark) to 120 mg/d (Finland) in men and from 49 mg/d (the Netherlands) to 84 mg/d (Finland) for women. This level of intake was less than the UL and when supplements and voluntary fortification were included. For the base diet, the P95 of selenium as % UL ranged from 23 to 40% in men and from 16 to 28% in women. The main sources of selenium are fish, meat and cereals.

The P95 of selenium intake from supplements alone ranged from 25 to 70 µg (data from three countries). Inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in a P95 intake of 65–134 µg (22–45% of UL) for men and women in those three countries.

Selenium intake – Children

The P95 intake of selenium in children and adolescents was less than the UL for base diet and when supplements and voluntary fortification were included (Fig. 7a and b).

Fig. 7.

(a) Selenium intake from the base diet. (b) Selenium intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Few data on intake of selenium from voluntary fortified foods are available and selenium is added to foods only infrequently (34).

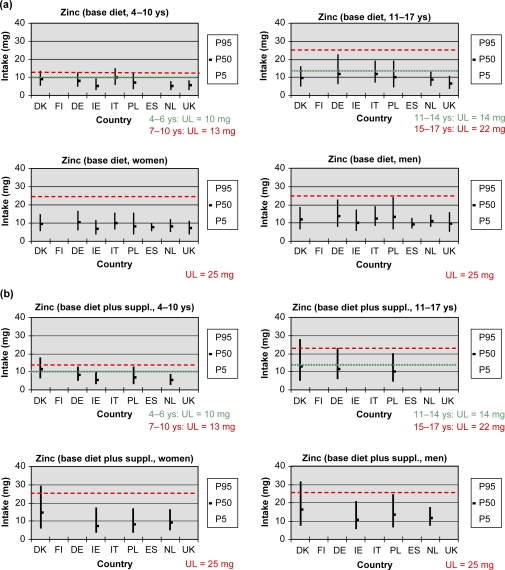

Zinc

Upper intake level (UL) for zinc

The UL for zinc for adults (25 mg) was derived on the basis of the evidence of absence of adverse effects on copper balance and status at total zinc intakes of about 50 mg/d in intervention studies in adults (3). ULs were derived for children by adjusting the adult UL for differences in body weight (3).

Zinc intake – Adults

For the base diet, the P95 intake of zinc ranged from 12 mg/d (Spain) to 24 mg/d (Poland) in men and from 10 mg/d (Spain) to 17 mg/d (Germany) in women. Higher intakes of zinc from the base diet are associated with high consumption of meat and cereal products (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8.

(a) Zinc intake from the base diet. (b) Zinc intake from the base diet plus supplements.

The P95 intake of zinc from supplements alone ranged up to 16 mg/d, and inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in an increase in P95 intake which was additive with P95 from base diet. For Denmark, inclusion of the contribution from supplements had a significant effect on the P95 intake, which exceeded the UL by 4–6 mg. The P95 intake of zinc from voluntarily fortified foods is low and inclusion of intake from voluntarily fortified foods with that from the base diet and supplements had little effect on P95 intake (Fig. 8b).

Zinc intake – Children

For children, the P95 of zinc intake from base diet ranged from 8 to 15 mg/d and 11–22 mg/d in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively, and exceeded the UL for 4–10-year-old children in some countries by a small amount (Fig. 8a).

The main sources of zinc in Germany and Poland are meat, meat products, bread and milk products.

The limited data available on intakes of zinc from supplements indicate that P95 of zinc intake from supplements in users only were 5 and 16 mg/d in Denmark, for age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively, and inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in an increase in P95 intake which was additive with P95 from base diet and which led to the P95 intake for both age groups exceeding the UL in that country (Fig. 8b).

The limited data available on intakes of zinc from fortified foods for these age groups indicate that intake from this source is low and that inclusion of this source with base diet has only a minimal effect on P95 intake.

Comment

The UL that has been established for zinc is low relative to the observed intakes and P95 intakes from base diet were close to UL for adults in some countries and exceeded the UL in children by small amounts in some countries. Based on data for only a few countries, the contribution of supplements to P95 intake was significant only for Denmark and inclusion of supplements led to P95 intake exceeding the UL in adults and children in that country. Zinc intake from voluntarily fortified foods is very low and zinc is added to foods only infrequently (34) There are no reported adverse health effects associated with the small proportions of children and adults exceeding UL for zinc and the SCF has indicated that the observed zinc intakes close to the UL in EU are not a matter of concern (3).

Vitamins

Folic acid

Upper intake level (UL) for folic acid

The UL for folic acid for adults (1,000 µg) was derived on the basis of the evidence for masking of undiagnosed vitamin B12 deficiency by folic acid with risk of progression of the vitamin B12 deficiency-related neuropathy (3). There is no evidence for risk associated with high intakes of natural, reduced folates and the UL applies to synthetic folic acid only. Although ULs were established for children by adjusting the adult UL on the basis of body weight, the population risk group is older adults in whom vitamin B12 deficiency may occur due to pernicious anaemia or malabsorption (3). Thus, the UL established in this way for children has little meaning since the adverse effect on which it is based is not relevant to this age group.

Folic acid intake – Adults

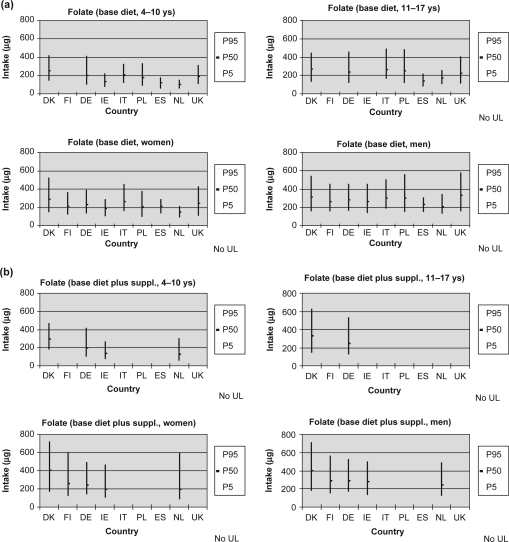

No country requires folic acid to be mandatorily added to foods, therefore, the base diet provides no folic acid as only natural folates occur in foods. Supplements and fortified foods (predominantly ready-to-eat cereals and some fat spreads) contain folic acid. Separate intakes from fortified foods are available only from the Irish data. However, the contribution from fortified fat spreads was available only for the children's survey. The P95 for folic acid intake in adults was much lower than the UL for intake from supplements and also when voluntary fortification was included (Ireland). The P95 intake of folic acid from supplements alone in men and women ranged up to about 360 µg/d, increasing to about 400 µg/d when voluntary fortification was included (Ireland; data not shown). Data on folic acid intake from fortified foods alone were available only for one country (Ireland) and ranged up to about 160 µg/d in adults.

Folic acid intake – Children

In 4–10-year-old children, the P95 intake of folic acid from supplements alone ranged up to about 40 µg/d (about 260 µg/d in 11–17 ys old), increasing to about 210 µg/d when voluntary fortification was included. Data on folic acid intake from fortified foods alone were available only for one country (Ireland) and ranged up to about 170 µg/d ( data not shown).

Fig. 9.

(a) Folate intake from the base diet. (b) Folate intake from the base diet plus supplements. (c) Folic acid intake from base diet.(d) Folic acid intake from base diet plus supplements.

Comment

Total intakes of folic acid vary considerably between countries but are well below the UL in adults even in high consumers. High intakes of folic acid are mainly associated with consumption of supplements and to a lesser extent with fortified foods (mainly fortified breakfast cereals).

In children, total intakes of folic acid also vary considerably between countries and for high consumers intakes are lower than in adults. High intakes of folic acid are associated with consumption of supplements and with fortified foods (mainly fortified breakfast cereals). As indicated earlier, it is not appropriate to apply the UL for folic acid derived from the adult UL by the SCF to children or adolescents since the adverse effect on which this UL is based is not relevant to this age group.

Niacin (Nicotinamide)

Niacin

Niacin is a collective term for nicotinic acid and nicotinamide, which are two related compounds with slightly different metabolic activity. Because of this they have separated ULs, being based on different adverse affects.

Upper intake levels (ULs) for nicotinic acid – Adults

The UL for nicotinic acid is set at 10 mg/d for free nicotinic acid. This was derived from occasional flushing seen at clinical doses in young subjects at 30 mg per day, using an uncertainty factor of 3. Such effects might cause transient hypotensive episodes in the elderly. This upper level is 300-fold below the dose frequently used clinically for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia (3 g/d)

Upper intake levels (ULs) for nicotinic acid – Children

The upper levels for children and adolescents were derived on the basis of their body weights. The UL does not apply during pregnancy or lactation due to lack of specific safety data. However, there is no evidence in these life stages of increased susceptibility from low doses of free nicotinic acid (3).

Nicotinic acid intakes

Nicotinic acid is not used for food fortification or the majority of food supplements. Therefore, it is present at negligible levels in foods.

Upper intake level (UL) for nicotinamide – Adults

Nicotinamide does not produce the above mentioned flushing. The UL for nicotinamide is 12.5 mg/kg body weight/d or approximately 900 mg/d for adults. This was derived from evidence of no adverse effect at doses up to 25 mg/kg body weight/d in prolonged studies in diabetic subjects. An uncertainty factor of 2 was applied.

Upper intake level (UL) for nicotinamide – Children

The upper levels for intake by children and adolescents were derived on the basis of their body weights. This is not applicable during pregnancy or lactation because of inadequate specific data associated with any risk during pregnancy or lactation There is evidence, from at least from one study, that an additional 15 mg is without adverse effect on pregnancy outcome.

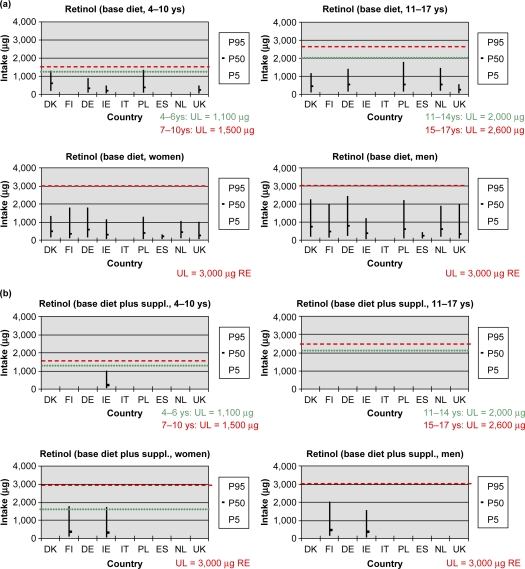

Nicotinamide intakes – Adults

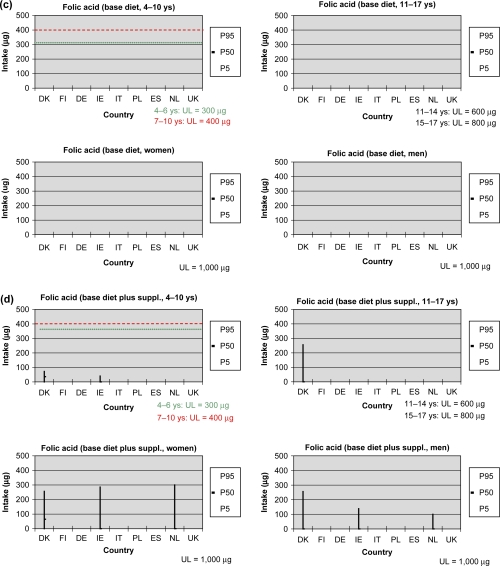

There are no concerns regarding intakes of nicotinamide (preformed niacin) within the range currently consumed in foods, from all sources including fortified foods and supplements, in European countries. Intakes at the 95th percentile from all sources are less than 10% of the UL for all ages (Fig. 10a and b refer only to nicotinamide and not to total niacin equivalents).

Fig. 10.

(a) Nicotinamide intake from the base diet. (b) Nicotinamide intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Total vitamin A

Vitamin A can be expressed as retinol equivalents (RE), which include retinyl esters, retinol (from animal foods) and carotenoids (mainly from plant foods).

Upper intake level (UL) for vitamin A

No UL has been established for total vitamin A. Whereas the UL for retinol will be discussed in the next section, due to insufficient scientific data, no UL for isolated β-carotene has been set.

Vitamin A intakes

For the base diet, the P95 intake of vitamin A ranged from about 750–3,900 µg/d in men and 700–3,700 µg/d in women (data not shown). The relatively higher intake in Germany, Poland and Italy may be associated with high consumption of sausages, liver (retinol) and vegetables. Inclusion of supplemental intake with that from the base diet resulted in a modest increase in P95 in Denmark and a strong increase in Finland. This may indicate that in these countries high consumers of vitamin A from base diet could also be high consumers of vitamin A supplements.

For children, the P95 of vitamin A intake from base diet ranged from 600 to 2,600 µg/d and 700 to 3,700 µg/d in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively. When supplements were included, the P95 intake increased considerably in the few countries with available data.

Retinol

Upper intake level (UL) for retinol

The UL for preformed vitamin A (retinol and retinyl esters) was derived on the basis of available data on the teratogenic potential of high vitamin A intake. The UL is set at 3,000 µg RE/d for women of child-bearing age, for whom teratogenicity is only relevant. This level is considered also to be appropriate for adult men, because the lowest chronic daily intake levels associated with hepatotoxicity are about 2.5-fold higher. The UL for children and adolescents are extrapolated from the UL for adults with corrections for different basal metabolic rate (UL in µg/d for children: 1,100 for ages 4–6 ys; 1,500 for ages 7–10 ys; 2,000 for ages 11–14 ys; and 2,600 for ages 15–17 ys). Although sufficient evidence is not yet available, the UL may not adequately address the risk of osteoporosis and bone fracture in vulnerable groups. Therefore, postmenopausal women are advised to restrict their intake to 1,500 µg RE/d (3).

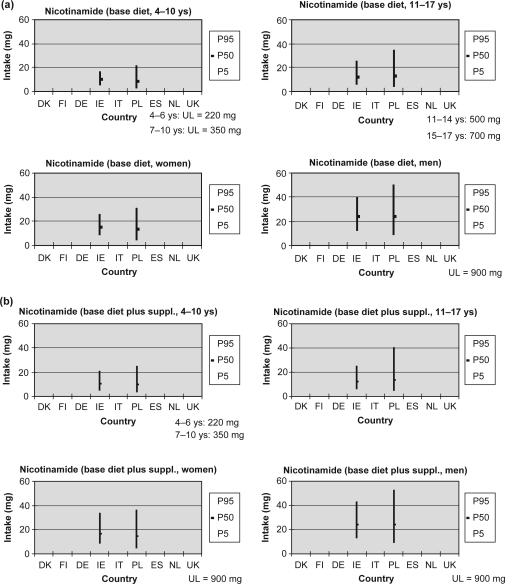

Retinol intakes – Adults

In adults, the P95 intake of retinol from base diet ranged from about 400 µg/d (Spain) to about 2,400 µg/d (Germany) in men and from about 280 µg/d (Spain) to about 1,770 µg/d (Finland). This corresponds to 13–80% and 10–58% of UL in men and women, respectively. The P95 intake of retinol does not exceed the UL (Fig. 11a).

Fig. 11.

(a) Retinol intake from the base diet. (b) Retinol intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Note: UL (retinol) for postmenopausal women: 1,500 µg RE.

The P95 intake of retinol from supplements alone ranged up to 940 µg/d (data not shown). In Ireland, the supplemental intake contributed significantly to an increase of the P95 intake from total diet. The P95 intake of retinol from voluntarily fortified foods is low and has little effect on the P95 intake of total diet. The P95 intake from total diet was less than UL (Fig. 11a).

Retinol intakes – Children

For children, the P95 of retinol intake from base diet ranged from 450 to 1,300 µg/d and 540 to 1,760 µg/d in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively. The P95 for 4–10-year-old children exceeds the UL in Poland and Denmark. The P95 for older children remains below the UL (Fig. 11a).

The limited data available on supplemental intake of retinol for children and adolescents indicate that the P95 intake from supplements alone ranged up to 900 µg/d. In Ireland and the United Kingdom, the supplemental intake contributed significantly to an increase of the P95 intake from total diet. The limited available data on intake from fortified foods indicate no significant contribution to total retinol intake (Fig. 11b).

Comment

Total intakes of retinol in adults vary considerably between countries, mainly due to different intakes from base diet and supplements. However, P95 intake does not exceed the UL. For 4–10-year-old children (but not in 11–17-year-old children), P95 of total intake approaches or exceeds the UL in Poland due to high intakes from base diet. The limited available data on intake from fortified foods indicate that intake of retinol from voluntarily fortified foods is low and has little effect on the P95 intake of total diet. Retinol is added to foods only infrequently (33, 34). It should be noted that foods, which are (semi) mandatorily fortified with retinol, e.g. margarine, fat spreads, were included in the base diet data.

Vitamin B6

Upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamin B6

The EC UL is based on neurotoxicity derived largely from data in women taking high dose supplements to treat premenstrual syndrome. Doses of 500 mg or more over a period of years can produce severe neurological effects. The EC UL of 25 mg/d was derived by applying a safety factor of 4 to 100 mg per day, which is the level at which minor neurological symptoms may be apparent following long-term consumption (36). No adverse effects have been reported for 25 mg per day in the large body of published research in this area.

No sub-groups are known to be especially sensitive to long-term consumption of high levels of vitamin B6, also not pregnant or lactating mothers. Therefore, the UL of 25 mg per day is also applied to this sub-group. The upper level intakes for children are based on body weight differences compared to adults.

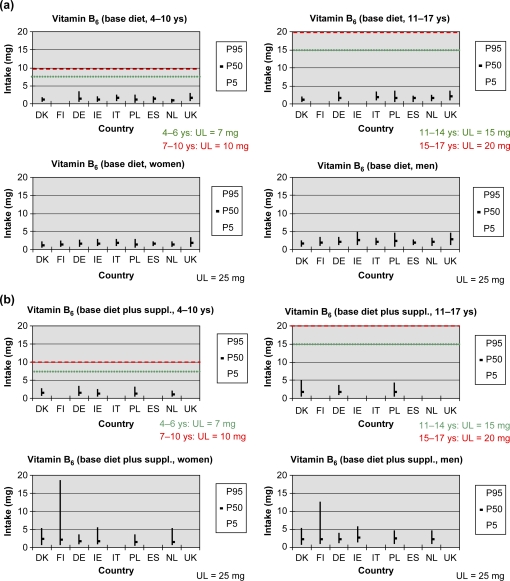

Vitamin B6 intakes

The 95th percentile intake from base diet ranged from 2.5 mg/d (Denmark) to 4.8 mg/d (Ireland) in men and from 2.0 mg/d (the Netherlands and Denmark) to 3.2 mg/d (United Kingdom) in women. The 95th percentile intake of vitamin B6 from the base diet is typically 8–19% of the UL for adults. For children this is higher, being approximately 13–33% UL in younger children, which changes to 19–33% of UL when supplements are included (Fig. 12b).

Fig. 12.

(a) Vitamin B6 intake from the base diet. (b) Vitamin B6 intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Women's intakes from supplements alone at the P95 level are 6–16% of the UL in most countries (data not shown). However, significantly higher levels are reported for Finland (48% UL). For supplements and base diet, the range of intakes in women increases slightly to 14–21% UL (74% UL in Finland). This is likely to be due to the wide spread use of vitamin B6 to relieve the symptoms of premenstrual tension (Fig. 12b).

Where data are reported separately for fortified foods, intakes range up to 5% UL for adults, up to 15–20% UL in children aged 4–10 ys and up to 20–27% UL in children aged 11–17 ys (data not shown).

Comment

In adults, the P95 of total intake of vitamin B6 (including supplements and voluntary fortification) is well below the UL, except in Finland where it is 74% of UL in women due mainly to intake from supplements. In children, supplements and fortified foods contribute significantly to intake in some countries; however, the P95 of total intake of vitamin B6 is well below the UL.

Vitamin D

Upper intake level (UL) for vitamin D

The UL for vitamin D for adults is derived on the basis of data on the risk of hypercalciuria/hypercalcaemia which has been demonstrated to increase in some parts of the population with a dietary intake above 100 µg vitamin D/d. Using an uncertainty factor of 2, the UL for adults is set at 50 µg vitamin D/d for adults (3).

For the age group 2–17 ys, there are no data on high-level intake to support the derivation of an UL. However, studies suggest that susceptibility towards vitamin D changes with age. Using a cautious approach and a lower body weight of children, the UL for children is set at 25 µg vitamin D/d for children from two up to and including 10 ys of age and at 50 µg vitamin D/d for adolescents 11–17 ys of age (3).

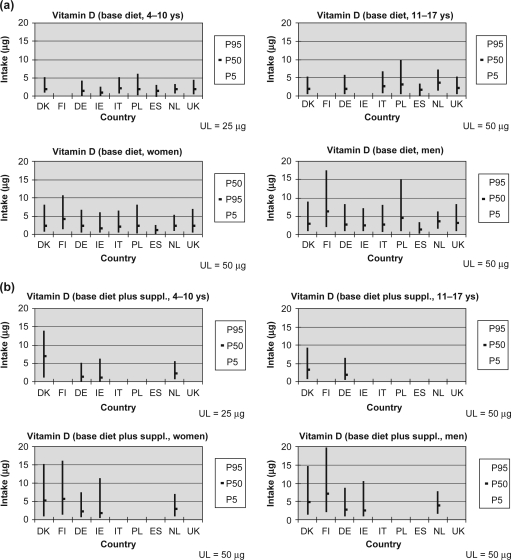

Vitamin D intakes

The P95 intake for vitamin D from base diet range from 3.1 µg/d (Spain) to 17.3 µg/d (Finland) in men and from 2.4 µg/d (Spain) to 10.5 µg/d (Finland) in women. These intakes were less than the UL both for the base diet and when supplements and fortification were included. For the base diet, the P95 of vitamin D intake ranged as percentage of UL from 6 to 35% in men and 5 to 21% in women. The higher levels observed in Finland, especially in men, are associated with vitamin D fortification of milk, which is semi-mandatory (Fig. 13a).

Fig. 13.

(a) Vitamin D intake from the base diet. (b) Vitamin D intake from the base diet plus supplements.

The P95 intake of vitamin D from supplements alone ranged up to 10 µg for both men and women (Finland). Inclusion of supplemental intake with intakes from base diet resulted in a wide range of increases, with the higher P95 values in Denmark and Finland where intake of supplements is relatively higher (Fig. 13b).

The P95 intake of vitamin D from voluntary fortified foods is low and inclusion of intake from voluntary fortified foods with that from the base diet and supplements had little effect on P95 intakes in both men and women.

For children and adolescents, the P95 of vitamin D intake from base diet ranged from 2.3 to 5.9 µg/d and 3.0–9.7 µg/d in the age groups 4–10 and 11–17 ys, respectively (Fig. 13a). From the limited data available, intake from supplements and fortified foods are low (except for supplements in Denmark) and inclusion of these sources with base diet has only a minimal effect on P95 intake (Fig. 13b).

Comment

In adults, the P95 of total intake of vitamin D (including supplements and voluntary fortification) is well below the UL, even in countries where there is a wide use of supplements (Denmark, Finland) and where there is semi-mandatory fortification of milk with vitamin D (Finland). In children, the P95 of total intake of vitamin D (including supplements and voluntary fortification) is well below the UL, even in countries where there is a wide use of supplements (Denmark).

The limited available data on intake from fortified foods indicate that intake of vitamin D from voluntarily fortified foods is low and has little effect on the P95 intake of total diet. Vitamin D is added to foods less frequently than some other nutrients (e.g. B-vitamins) and amounts added are moderate (33, 34). It should be noted that foods, which are (semi) mandatorily fortified with vitamin D, e.g. margarine, fat spreads (and milk for some countries) were included in the base diet data.

Vitamin E

Upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamin E

The UL for vitamin E for adults (300 mg) was derived on the basis of evidence of reduced blood clotting at intakes above about 500 mg/d in an intervention study in adults. ULs were derived for children by adjusting the adult UL for differences in body surface area (3).

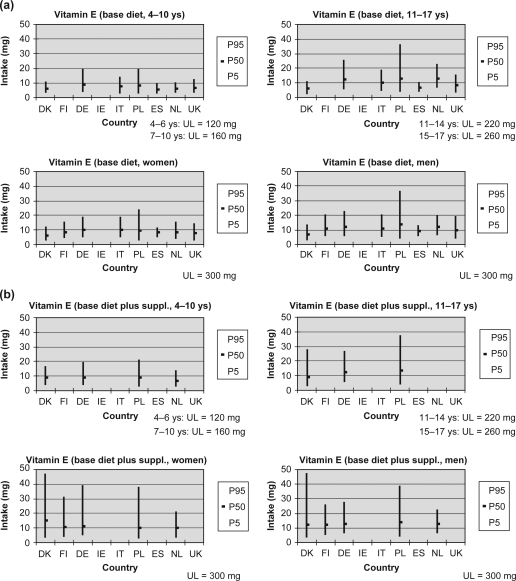

Vitamin E intakes

The P95 intake of vitamin E from base diet ranged from around 13 mg/d (Spain) to 36 mg/d (Poland) in men and from around 11 mg/d (Spain) to 24 mg/d (Poland) in women (Fig. 14a and b). These intakes were well below the UL for base diet and, for adults, did not exceed 16% of UL even when supplements and voluntary fortification were included. Higher intakes of vitamin E from the base diet are associated with high consumption of oils, fruits, vegetables and cereals. The P95 intake from supplements alone ranged up to about 40 mg/d in adults and about 20 mg/d in children and adolescents while intakes from voluntarily fortified foods were very low (data not shown).

Fig. 14.

(a) Vitamin E intake from base diet. (b) Vitamin E intake from the base diet plus supplements.

Discussion

The intake data reported here are based on national representative samples of adults and children conducted by institutes or working groups with long experience with such surveys and therefore are the best available estimates for intake distributions. Not all surveys estimated the separate contribution of food supplement use and the differences in the assessment of the intake of food supplements and the databases used to calculate the intake from supplements should be kept in mind when interpreting the data. Few surveys were able to specifically measure separately the contribution of fortified foods. As the main focus of this report is on intakes at the upper end of the intake distribution, low energy reporters were not excluded from the analysis. Energy underreporting is less likely to affect the higher end of the intake distribution than the lower end (Flynn, personal communication, 2007). Over-reporting is expected to be less frequent in dietary surveys and no attempt was made to correct for that. Because of differences in methods used to estimate food consumption, each with its own limitations, differences in intakes between countries should be interpreted cautiously. This is particularly true for food supplements for which methods to estimate their contribution to habitual intakes of micronutrients are not standardised. In addition, data on consumption of fortified foods is very limited or not existent for most countries. For those countries that are not able to differentiate between the natural and voluntary fortified content of nutrients in a food item, the intake of the ‘base diet’ may thus be overestimated.

Intake of nutrients in high consumers was compared to the tolerable UL. This is the daily amount of a nutrient, which can be consumed over a prolonged period with negligible risk of adverse health effects (3). The use of UL for assessment of risk in populations should take account of the basis on which the UL was derived, e.g. the specific adverse effect on which the UL was based, and whether the specific population group is susceptible to that effect. For example, the adverse effect for which the UL for folic acid is based is masking of undiagnosed vitamin B12 deficiency by folic acid with risk of progression of the vitamin B12 deficiency-related neuropathy (3). The population group at risk for this adverse effect is older adults in whom vitamin B12 deficiency may occur due to pernicious anaemia or malabsorption (3). Thus, although UL for folic acid has been derived for children by adjusting the adult UL on the basis of body weight, it is inappropriate to use these UL for assessment of risk of adverse effects in children since the adverse effect on which the UL are based is not relevant to this age group. For some nutrients (iron and phosphorus) EFSA has established no ULs.

For most nutrients, adults and children generally consume considerably less than the UL, even when the total intakes from non-fortified foods, fortified foods and food supplements are combined. Even in high consumers, P95 total intakes are significantly lower than UL for most nutrients. Total nutrient intake in high consumers, expressed as % UL is generally higher in children than in adults. This reflects the fact that the lower UL for children is derived on the basis of body weight. However, children generally have a higher intake of food and nutrients expressed per kg body weight compared to adults. This underlines the fact that children are the most vulnerable group to exceed the ULs.

For zinc, copper, iodine and retinol the UL is low relative to the observed intakes, particularly in children (3). This is also the case for magnesium (from supplements) in Finland. Intake of zinc from base diet in high consumers approaches the UL in adults and exceeded the UL in children by small amounts in some countries. For younger children (4–10 ys old) intake of iodine and retinol from base diet in high consumers is close to the UL and, when supplements are included, may exceed the UL by a small amount in some countries. For children, intake of copper from base diet in high consumers approaches or exceeds the UL in some countries. There are no reported adverse health effects associated with children and adults exceeding UL for retinol and zinc. It should be borne in mind that UL are established using uncertainty factors to ensure that at this level of intake the risk of adverse effects is negligible even for the most sensitive individuals in the population, including the children. Consequently, while intake exceeding the UL is not without some risk, the probability of adverse effects occurring in the small proportion of individuals exceeding the UL by a modest amount is low. For iodine, adverse effects are sometimes associated with excess intake in national fortification programmes to address iodine deficiency in the population and it is recognised that these populations are more sensitive to iodine exposure (3).

For calcium, intake from base diet in high consumers (adults) is close to UL, particularly in men, in some countries (Denmark, Finland and Germany), due to their high consumption of milk and dairy products. However, total intake (including supplements and fortified foods) in high consumers does not exceed the UL. Patterns of consumption of calcium containing supplements and fortified foods appear to be unlikely to lead to excessive calcium intakes overall. For example, high consumers of calcium from supplements are generally not high consumers of calcium from the base diet and intakes of calcium from fortified foods may replace, rather than add to, intakes of calcium from non-fortified natural sources of calcium. Furthermore, based on current practice, the proportion of food energy likely to be fortified with calcium may be much lower than for some other micronutrients and the levels of added calcium in foods appear to be modest. These findings suggest that models for estimating maximum safe levels of addition of micronutrients to foods and supplements may be conservative for calcium because they do not take into account likely patterns of consumption. They also emphasise the need to examine patterns of consumption of supplements and fortified foods on a nutrient by nutrient basis.

The main source of nutrients in high consumers is base diet and, in some cases, base diet and food supplements. For example, milk and dairy products are the main source of calcium in high consumers of this nutrient while for retinol, the main source of retinol for high consumers is liver (or sausages containing liver) and meat products in the base diet, particularly in Poland and Germany. The main source of zinc in high consumers is the base diet (and food supplements in Denmark). In the present study, fortified foods do not significantly contribute to high intakes for any nutrient, even in countries with a well-established history of voluntary food fortification such as the United Kingdom and Ireland. This may be explained by the moderate levels of nutrients in fortified foods that are nutritionally significant but not excessive as well as relatively low intakes of fortified foods even in high consumers of those foods at the time of the dietary survey (31, 33).

There are large differences between countries in the patterns of use of food supplements, e.g. Finland and Denmark have more widespread use of supplements and a greater intake of nutrients from this source and they may provide some indication of how patterns of supplement consumption might evolve in other countries in the future. Similarly, patterns of consumption of fortified foods in countries with a well-established history of voluntary food fortification such as the United Kingdom, Ireland and Germany might provide a useful starting point for projections of how intake of nutrients from fortified foods might develop in other countries where voluntary fortification is currently at a lower level.

The limited availability of data on the contribution of supplements and fortified foods to nutrient intake highlights the need for careful interpretation of available data. It also highlights the need for national food consumption surveys to adapt methodology for surveys to include estimates from these sources. There is also a need to develop improved methods for estimating intakes of micronutrients from fortified foods and food supplements in such surveys.

Conclusions

The major contributor to intakes for all nutrients and in all countries is from foods in the base diet.

Patterns of food supplements and voluntary fortification vary widely between countries, with food supplements being responsible for the largest differences in total intakes.

As far as we can assess, the risk of excessive intakes is relatively low for majority of the nutrients; possible exceptions being retinol, zinc, iodine, copper and magnesium. Children are more likely to exhibit higher intakes relative to the UL.

Each country used different methodologies to estimate food and supplement intake. However, few had the capacity to estimate the separate contribution from fortified foods.

The application of more precise food intake methods may be required for the future, to enable the estimation of nutrient intakes from both food supplements and fortified foods.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Janneke Verkaik-Kloosterman from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment for work done on the Netherlands data, Sigrid Gibson from Sig-Nurture Ltd for work on the United Kingdom data, Evelyn Hannon from University College Cork for work on the Irish data, Tue Christensen for work on the Danish data and Maciej Oltarzewski for work on the Poland data. Finally, the editorial work of Fiona Samuels, ILSI Europe is greatly appreciated.

This work was commissioned by the Addition of Nutrients to Food Task Force of the European branch of the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI Europe). Industry members of this task force are Azko Nobel – National Starch Chemicals, BASF, Coca-Cola Europe, DSM, Groupe Danone, Kellogg Europe, Kraft Foods, Nestlé, Red Bull and Unilever. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of ILSI Europe.

Appendix.

Table I.

Calcium intake from the base diet, and base diet and supplements

Nutrient: Calcium (mg): age group: 4–10 ys

| Countries | Number of subjects | Mean energy intake (kJ) | P95 energy intake (kJ) | Base diet (including mandatory fortified foods) | Base diet plus supplements | Base diet plus supplements plus fortified foods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | ||||

| Denmark | 783 | 8,187 | 11,315 | 591 | 1,015 | 1,721 | 1,060 | 614 | 1,049 | 1,775 | 1,096 | ||||

| Finland | |||||||||||||||

| Germanya | 1,234 | 7,400 | 10,200 | 432 | 851 | 1,352 | 870 | 433 | 854 | 1,352 | 874 | ||||

| Irelandb | 446 | 4,620 | 2,186 | 389 | 714 | 1,283 | 749 | 389 | 720 | 1,296 | 758 | 455 | 822 | 1,400 | 847 |

| Italy | 107 | 8,248 | 11,494 | 469 | 769 | 1,196 | 798 | ||||||||

| Polandc | 455 | 8,296 | 13,499 | 164 | 553 | 1,134 | 595 | 167 | 553 | 1,134 | 598 | ||||

| Spain | 723 | 7,627 | 9,694 | 620 | 867 | 1,123 | 867 | 658 | 894 | 1,151 | 898 | ||||

| The Netherlandsd | 639 | 6,456 | 8,064 | 351 | 694 | 1,155 | 716 | 357 | 702 | 1,165 | 724 | 442 | 791 | 1,247 | 811 |

| United Kingdom | 835 | 6,712 | 9,082 | 382 | 667 | 1,107 | 700 | ||||||||

a6–11 ys.

bNo data available for four-year-old children.

cOut of 455 were 96 supplements users.

d4–6 ys, DNFCS-kids 2005/2006.

Nutrient: Calcium (mg): age group: 11–17 ys

| Countries | Number of subjects | Mean energy intake (kJ) | P95 energy intake (kJ) | Base diet (including mandatory fortified foods) | Base diet plus supplements | Base diet plus supplements plus fortified foods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | ||||

| Denmark | 588 | 8,921 | 13,454 | 525 | 1,047 | 1,905 | 1,116 | 544 | 1,096 | 1,953 | 1,158 | ||||

| Finland | |||||||||||||||

| Germanya | 1,272 | 11,326 | 19,261 | 648 | 1,235 | 2,400 | 1,337 | 650 | 1,238 | 2,422 | 1,350 | 689 | 1,296 | 2,515 | 1,396 |

| Ireland | |||||||||||||||

| Italy | 132 | 10,008 | 14,675 | 461 | 819 | 1,420 | 866 | ||||||||

| Polandb | 581 | 11,221 | 19,609 | 163 | 623 | 1,484 | 697 | 163 | 625 | 1,491 | 701 | ||||

| Spain | 1,137 | 8,854 | 12,014 | 580 | 854 | 1,231 | 878 | 589 | 877 | 1,267 | 900 | ||||

| The Netherlands | 616 | 9,999 | 13,991 | 516 | 955 | 1,560 | 986 | ||||||||

| United Kingdom | 768 | 7,895 | 11,559 | 328 | 708 | 1,266 | 742 | 328 | 710 | 1,266 | 743 | ||||

a12–17 ys.

bOut of 581 were 65 supplements users.

Nutrient: Calcium (mg): age group: >18 ys, women

| Countries | Number of subjects | Mean energy intake (kJ) | P95 energy intake (kJ) | Base diet (including mandatory fortified foods) | Base diet plus supplements | Base diet plus supplements plus fortified foods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | P5 | P50 | P95 | Mean intake | ||||

| Denmark | 2,375 | 8,171 | 11,821 | 455 | 949 | 1,689 | 995 | 499 | 1,024 | 1,831 | 1,080 | ||||

| Finland | 1,095 | 6,582 | 9,565 | 451 | 925 | 1,619 | 965 | 476 | 998 | 1,777 | 1,045 | 509 | 1,050 | 1,857 | 1,099 |

| Germany | 2,267 | 7,926 | 12,143 | 562 | 1,053 | 1,860 | 1,119 | 568 | 1,082 | 1,948 | 1,150 | ||||

| Ireland | 717 | 7,640 | 10,994 | 344 | 667 | 1,140 | 694 | 347 | 687 | 1,195 | 720 | 350 | 704 | 1,208 | 742 |

| Italy | 925 | 9,126 | 12,948 | 477 | 812 | 1,304 | 843 | ||||||||

| Polanda | 1,656 | 8,317 | 12,743 | 156 | 457 | 1,113 | 516 | 157 | 462 | 1,121 | 523 | ||||