Abstract

The transition from naïve to activated T cells is marked by alternative splicing of pre-mRNA encoding the transmembrane phosphatase CD45. Using a short hairpin RNA interference screen, we identified heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein L-like (hnRNPLL) as a critical inducible regulator of CD45 alternative splicing. HnRNPLL was up-regulated in stimulated T cells, bound CD45 transcripts, and was both necessary and sufficient for CD45 alternative splicing. Depletion or overexpression of hnRNPLL in B and T cell lines and primary T cells resulted in reciprocal alteration of CD45RA and RO expression. Exon array analysis suggested that hnRNPLL acts as a global regulator of alternative splicing in activated T cells. Induction of hnRNPLL during hematopoietic cell activation and differentiation may allow cells to rapidly shift their transcriptomes to favor proliferation and inhibit cell death.

It is estimated that greater than 75% of genes yield alternative transcripts, contributing to considerable functional diversity within the genome (1, 2). SR (serine-arginine rich) proteins are key positive regulators of alternative splicing that bind enhancer sequences on nascent transcripts and recruit spliceosomal proteins to weak splice sites, thereby facilitating proximal spliceo-some assembly (3). Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) also regulate splicing by binding negative cis-regulatory elements and causing exon exclusion from mature mRNA (3). SR proteins and hnRNPs function as antagonists in alternative splicing, with binding of hnRNPs to silencer sequences inhibiting SR protein binding, thus forcing a shift of splicing to distal splice sites (4).

CD45 is an abundant transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed at the surface of T cells, B cells, and other hematopoietic cells (5). CD45 transcripts undergo extensive alternative splicing in which exons 4, 5, and 6 are variably excluded (Fig. 1A) (6). Primary naive T cells and B cells express the larger isoforms and are referred to as RA+. In contrast, activated and memory T cells express the shortest isoform, CD45RO (5). CD45 initiates signaling through antigen receptors by dephosphorylating the inhibitory tyrosine on Src-family kinases (5), but attributing specific functions to individual CD45 isoforms has been complicated by the high basal expression of CD45 in lymphocytes and its ability to dephosphorylate both inhibitory and activation-loop tyrosines of Src-family kinases (7–9). Stimulated T cells show a shift in CD45 alternative splicing that culminates in increased CD45RO and decreased CD45RA+ transcripts within 24 hours, and this can be blocked by cycloheximide treatment, which suggests the involvement of de novo protein synthesis (10).

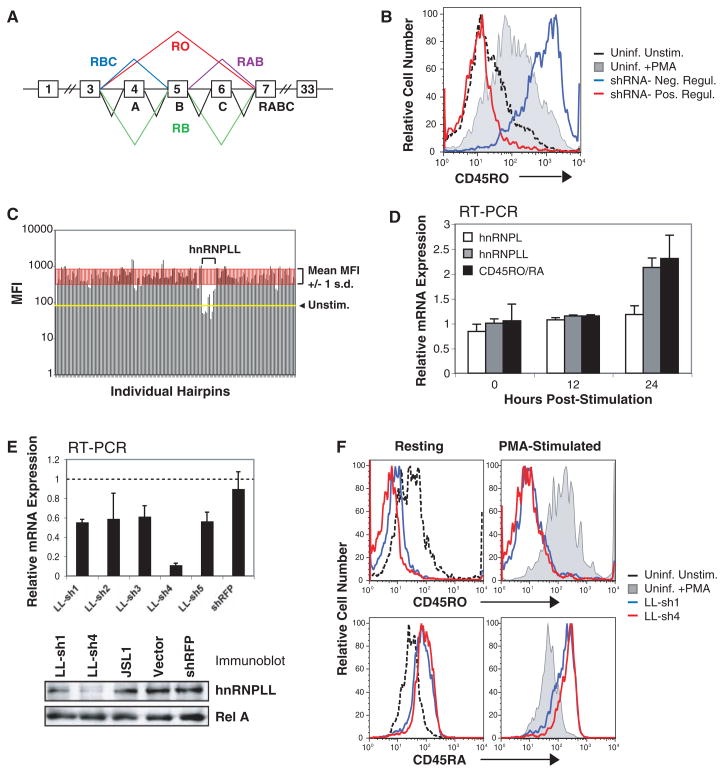

Fig. 1.

Identification of hnRNPLL in an shRNA screen. (A) CD45 isoform nomenclature. (B) Sample histogram of cell surface-CD45RO expression in uninfected JSL1 cells with or without PMA stimulation and JSL1 cells transduced with lentiviral shRNAs. (C) Representative results from a single 96-well plate in the screen. All hnRNPLL hairpins decreased PMA-induced CD45RO expression. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR for hnRNPLL, hnRNPL, CD45RO, and CD45RA in JSL1 cells stimulated with PMA for 12 and 24 hours. PMA stimulation increases hnRNPLL expression and the ratio of CD45RO to RA transcripts. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR and anti-hnRNPLL immunoblot confirmed hnRNPLL depletion. (F) Cell-surface expression of CD45 isoforms assessed in PMA-stimulated JSL1 cells stably expressing LL-sh1 and LL-sh4. HnRNPLL depletion decreased CD45RO expression and increased CD45RA expression.

To identify trans-acting factors required for CD45RO expression in stimulated T cells, we performed an RNA interference (RNAi) screen in JSL1 T cells, which basally express both CD45RO and CD45RA, but in which phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation generates a relative increase in the ratio of RO to RA transcripts through alternative splicing (10). JSL1 cells were infected in duplicate with individual short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) from a splicing factor–directed library (11, 12), selected with puromycin, stimulated with PMA (40 hours), and assayed for CD45RO expression (Fig. 1B). Knockdown of a single candidate, hnRNPLL (heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein L-like), substantially reduced PMA-induced CD45RO expression, with three of the five hairpins reducing it to a level lower than the unstimulated control (Fig. 1C).

Concurrent with the increased ratio of CD45RO to RA transcripts, PMA stimulation of JSL1 cells increased hnRNPLL transcripts by a factor of ~2.0 in 24 hours (Fig. 1D), without affecting expression of its paralog hnRNPL (heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein L). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that hnRNPLL is the de novo synthesized factor that promotes alternative splicing in PMA-stimulated JSL1 cells (10).

In JSL1 cells engineered for stable expression of two of the five lentiviral shRNAs (LL-sh1 and LL-sh4), a substantial reduction of hnRNPLL protein expression was also observed (Fig. 1E). Cells expressing these shRNAs showed decreased CD45RO expression, and a concomitant increase in CD45RA expression, under both resting and stimulated conditions (Fig. 1F). This result is consistent with the notion that hnRNPLL mediates alternative splicing rather than repressing CD45 transcription.

To further examine the influence of hnRNPLL expression, JSL1 cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding bicistronic hnRNPLL and internal ribosomal entry site–green fluorescent protein (IRES-GFP) as a means of tracking hnRNPLL expression in these cells. HnRNPLL overexpression was readily apparent in the total cell population (Fig. 2A), even though only ~35% of the cells were successfully transduced as judged by GFP expression (fig. S1). The entire population of hnRNPLL-expressing (GFP+) cells up-regulated CD45RO, and CD45RA expression was eliminated (Fig. 2B). Thus, hnRNPLL expression is both necessary and sufficient for CD45 alternative splicing and CD45RO expression in JSL1 cells.

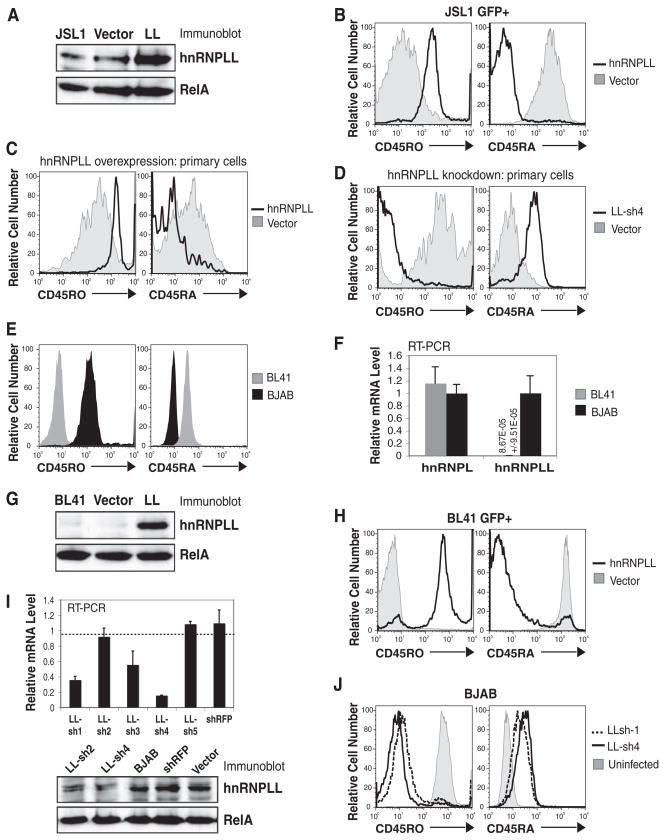

Fig. 2.

Overexpression or knockdown of hnRNPLL influences CD45 alternative splicing. (A) Immunoblot for hnRNPLL expression in JSL1 cells retrovirally transduced with IRES-GFP hnRNPLL or empty vector. (B) HnRNPLL over-expression in GFP+ JSL1 cells increased CD45RO and decreased CD45RA expression in the absence of stimulation. (C) Increased CD45RO expression and decreased CD45RA expression in GFP+, hnRNPLL-transduced primary human CD4+ T cells. (D) Reduced CD45RO expression and increased CD45RA expression in hnRNPLL-depleted primary CD4+ T cells. (E) CD45 isoform expression in BJAB and BL41 B cell lines. (F) Detection of hnRNPLL transcripts in BJAB but not BL41 cells (value shown numerically) by quantitative RT-PCR. (G) Immunoblot for hnRNPLL expression in BL41 cells retrovirally transduced with IRES-GFP hnRNPLL or empty vector. (H) Increased CD45RO and decreased CD45RA expression in GFP+ hnRNPLL-transduced BL41 cells. (I) Quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot for hnRNPLL in knockdown BJAB cells. (J) Decreased CD45RO and increased CD45RA expression in LL-sh1 and LL-sh4 BJAB cells.

We next tested the ability of hnRNPLL to influence CD45 isoform expression in primary human CD4+ Tcells. Stimulated naïve CD4+ Tcells were infected with lentiviruses encoding IRES-GFP hnRNPLL (for overexpression) or LL-sh4 (for RNAi-mediated knockdown) and cultured in interleukin-2–containing medium for 5 to 7 days. As expected, mock-infected primary T cells up-regulated CD45RO and down-regulated CD45RA after activation, and this was also seen in hnRNPLL-expressing (GFP+) T cells, but to a greater extent (Fig. 2C). In contrast, primary T cells depleted of hnRNPLL were 100% CD45RO− and CD45RA+ (Fig. 2D).

Unlike T cells, which readily undergo CD45 alternative splicing upon activation, B cells are refractory to the CD45RA > RO switch, and PMA stimulation of B cell lines does not promote exon 4 to 6 exclusion and consequent CD45RO expression (10, 13). Most B cell lines constitutively express high levels of the largest isoform, CD45RABC (B220) and do not express CD45RO (e.g., BL41) (Fig. 2E). While screening additional B cell lines for CD45 isoform expression, however, we found that BJAB B cells are 100% positive for CD45RO and do not express CD45RA+ isoforms (Fig. 2E). HnRNPLL expression directly correlated with CD45 isoform expression in these two cell lines, with virtually undetectable CD45RO and hnRNPLL in BL41 cells (Fig. 2, E to G) and high levels of hnRNPLL and CD45RO in BJAB cells (Fig. 2, E, F, and I). Transcript levels of the paralog, hnRNPL, were similar in the two cell lines (Fig. 2F). When hnRNPLL was overexpressed in BL41 cells using an IRES-GFP lentiviral expression plasmid (Fig. 2G and fig. S1), a total population shift was seen, such that infected (GFP+) cells uniformly expressed CD45RO and lost expression of CD45RA+ isoforms (Fig. 2H). Conversely, depletion of hnRNPLL with LL-sh1 and LL-sh4 shRNAs in BJAB cells decreased hnRNPLL transcript and protein expression (Fig. 2I) and caused a total population shift of the infected cells to CD45ROlow and CD45RA+ (Fig. 2J). These data confirm an important role for hnRNPLL in CD45 alternative splicing in T cells and also in B cells.

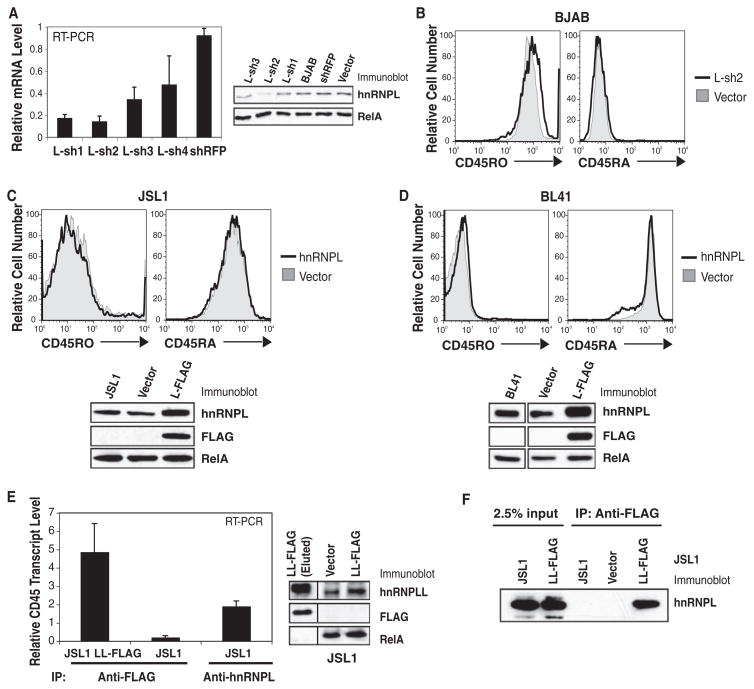

The paralog of hnRNPLL, hnRNPL, was previously identified as binding to an exonic splicing silencer, ESS1, located in exon 4 of CD45 (14, 15). However, it was not identified in our screen (fig. S2A), and we traced this to an inability to knock down hnRNPL protein expression effectively in JSL1 cells (fig. S2B). In BJAB cells however, L-sh2 substantially diminished hnRNPL expression (Fig. 3A, left), with no observable effect on CD45 isoform expression (Fig. 3B). Conversely, overexpression of hnRNPL, either in JSL1 or BL41 cells, had no effect on CD45 isoform expression (Fig. 3, C and D). Given the homology between hnRNPL and hnRNPLL (69% identity at the amino acid level) (16), we confirmed that hnRNPLL knockdown did not result in an “off-target” decrease in hnRNPL expression (fig. S2C).

Fig. 3.

Effect of hnRNPL on CD45 isoform expression. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblot for hnRNPL in knockdown BJAB cells. (B) Cell-surface CD45 isoform expression was unaltered in L-sh2 BJAB cells. (C) JSL1 and (D) BL41 cells retrovirally transduced with FLAG-tagged hnRNPL (L-FLAG) were immunoblotted for hnRNPL and FLAG proteins. HnRNPL overexpression did not affect CD45 isoform expression. (E) FLAG-tagged hnRNPLL (LL-FLAG) or endogenous hnRNPL was immunoprecipitated from stably transduced or uninfected JSL1 cells with antibody to FLAG or antibody to hnRNPL (anti-L), respectively. Associated RNA was isolated, and quantitative RT-PCR was performed to detect CD45 transcripts. Immunoblot of LL-FLAG–transduced JSL1 cells indicated that hnRNPLL was not over-expressed relative to endogenous hnRNPLL. (F) Anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation from LL-FLAG–transduced JSL1 cells followed by immunoblotting for hnRNPL.

We next used RNA-immunoprecipitation (RIP) (17) followed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to test the association between hnRNPLL and CD45 transcripts. Because the only commercially available antibody directed against hnRNPLL is not suitable for immunoprecipitation, FLAG-tagged hnRNPLL or empty vector were stably expressed in JSL1 cells. Cells overexpressing FLAG-hnRNPLL showed only a marginal increase in total hnRNPLL detected with an antibody to hnRNPLL (Fig. 3E, right). Moreover, FLAG-hnRNPLL could not be detected in lysates by immunoblotting with an antibody to FLAG, although it was detected upon loading high amounts of anti-FLAG immunoprecipitate (Fig. 3E and fig. S3C). Nevertheless, anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates from FLAG-hnRNPLL-expressing JSL1 cells showed enrichment of CD45 transcripts (exon 4 sequences) by a factor of 20 relative to vector-transduced cells (Fig. 3E). Based on CD45 transcript expression in 5% of the input fraction, we calculated that the FLAG-hnRNPLL immunoprecipitates bound ~0.25% of all CD45 transcripts in the lysates. By comparison, immunoprecipitates of endogenous hnRNPL from untransduced JSL1 cell lysates bound ~0.09% of all CD45 transcripts in the lysates (Fig. 3E) (12). We also found that endogenous hnRNPL robustly coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-hnRNPLL (Fig. 3F), showing that the two proteins interact with each other and with CD45 transcripts.

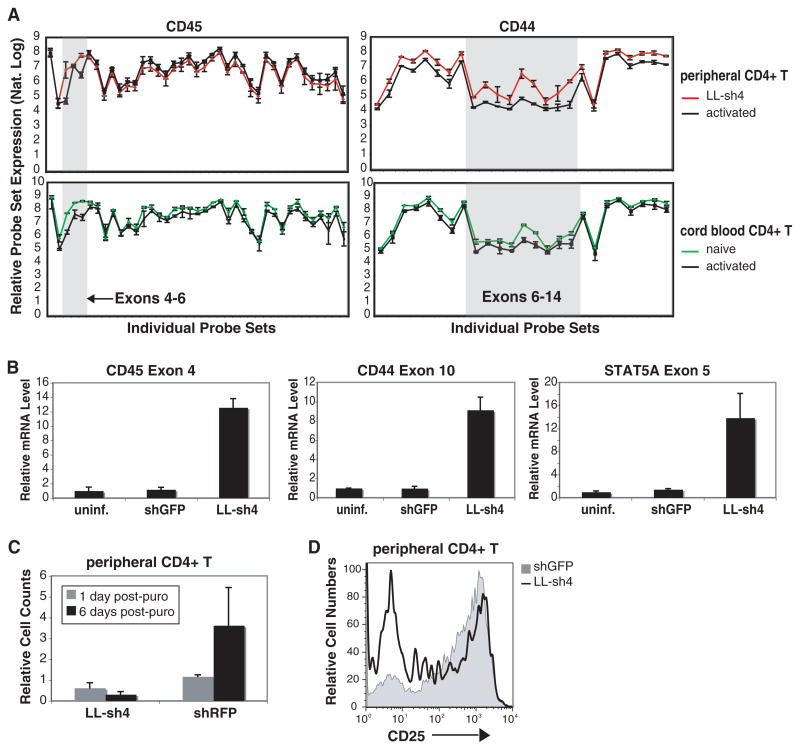

Exon array analysis (18) was next used to test the possibility that hnRNPLL regulates a broader program of alternative splicing in activated T cells. A total of 132 genes, including CD45 (protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C) itself (Fig. 4A), showed significant alternative exon usage (P < 0.01) in response to hnRNPLL knockdown, but not in response to shGFP infection (table S3). Of these, 36 genes showed significant alternative usage of corresponding exons in response to activation of cord blood cells (table S4), correlating with an increase in hnRNPLL expression by a factor of 5 in the activated cells. Expression of CD45 exons 4 and 6 was elevated in naïve cord blood and hnRNPLL-depleted peripheral T cells, relative to their expression in activated cord blood and peripheral T cells, respectively (Fig. 4A, left). Similarly, expression of CD44 exons 6 to 14, particularly exons 7 and 10, was increased in conditions lacking hnRNPLL (naïve or hnRNPLL-depleted cells) compared with activated cord blood and peripheral T cells (Fig. 4A, right) (6). Increased exon retention in response to hnRNPLL depletion was confirmed in peripheral T cells by RT-PCR for CD45 exon 4 and CD44 exon 10, as well as for STAT5A exon 5 (Fig. 4B). There is evidence for the existence of both latter transcripts (fig. S4B) (19). A complete analysis of alternative exon usage patterns and their potential functional consequences is being pursued.

Fig. 4.

HnRNPLL is a global regulator of alternative splicing in activated T cells. (A) Exon array analysis of RNA from activated peripheral CD4+ T cells, LL-sh4–transduced peripheral CD4+ T cells, naïve cord blood CD4+ T cells, and activated cord blood CD4+ T cells. As shown for CD45 and CD44 transcripts, low hnRNPLL expression (hnRNPLL knockdown or naïve cord blood) is associated with increased retention of select exons. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR for retained CD45, CD44, and STAT5A exons in hnRNPLL-depleted peripheral CD4+ T cells. (C) HnRNPLL-depletion in peripheral CD4+ T cells blocks proliferation. (D) Reduced CD25 expression in hnRNPLL-depleted peripheral CD4+ T cells.

Primary Tcells lentivirally infected with LL-sh4 (shRNA directed against hnRNPLL) were consistently difficult to expand, in contrast to primary T cells infected with control shRNA directed against red fluorescent protein (RFP) (Fig. 4C). Moreover, these hnRNPLL-depleted T cells repeatedly showed reduced expression of CD25 compared with control shRFP-expressing cells (Fig. 4D). These data are consistent with our finding that hnRNPLL targets not only CD45 (Figs. 1 to 3 and Fig. 4A) but also STAT5A (Fig. 4B) and diverse other proteins involved in cell proliferation, activation, and cell death (tables S3 and S4).

Our data strongly suggest that hnRNPLL is a “master regulator” of alternative splicing in activated T cells. HnRNPLL is induced upon T cell stimulation and as such is likely to correspond to the inducible, cycloheximide-sensitive factor postulated to promote the CD45RA > RO transition during Tcell activation (10). Depletion of hnRNPLL causes an overall shift in patterns of alternative splicing, which by and large are in the opposite direction from those seen in activated T cells in which hnRNPLL expression is increased. Induction of hnRNPLL during the process of Tcell activation and differentiation may represent a mechanism by which the cell can rapidly shift its transcriptome to favor proliferation and inhibit cell death.

There is increasing evidence that splicing and pre-mRNA processing involve multiprotein complexes in which individual components influence distinct aspects of transcript production (20, 21). Several proteins, including hnRNPL, PSF (poly-pyrimidine tract binding protein–associated splicing factor), and hnRNPE2, have been shown to bind CD45 transcripts (14, 15). However, none of these factors is induced upon T cell activation (14, 15), and only PSF (splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich) was identified in our screen, albeit as a weak hit (table S2). Together with its associated factors, hnRNPL may influence diverse aspects of CD45 pre-mRNA processing, including basal splicing, mRNA stability, and export (22, 23). After activation, hnRNPLL induction and recruitment to CD45 transcripts may then lead to the assembly of a high-affinity exon repression complex that mediates efficient CD45RO production as well as global changes in alternative splicing.

Supplementary Material

References and Notes

- 1.Johnson JM, et al. Science. 2003;302:2141. doi: 10.1126/science.1090100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modrek B, Lee C. Nat Genet. 2002;30:13. doi: 10.1038/ng0102-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DL. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matlin AJ, Clark F, Smith CW. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:386. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermiston ML, Xu Z, Weiss A. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch KW. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:931. doi: 10.1038/nri1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmond RJ, McNeill L, Holmes N, Alexander DR. Int Immunol. 2008;20:819. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes N. Immunology. 2006;117:145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNeill L, et al. Immunity. 2007;27:425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch KW, Weiss A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:70. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.70-80.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffat J, et al. Cell. 2006;124:1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 13.Trowbridge IS, Thomas ML. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothrock CR, House AE, Lynch KW. EMBO J. 2005;24:2792. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melton AA, Jackson J, Wang J, Lynch KW. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6972. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00419-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shur I, Ben-Avraham D, Benayahu D. Gene. 2004;334:113. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenenbaum SA, Lager PJ, Carson CC, Keene JD. Methods. 2002;26:191. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore MJ, Silver PA. RNA. 2008;14:197. doi: 10.1261/rna.868008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Biotechnology Information Database. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gene.

- 20.Ma XM, Yoon SO, Richardson CJ, Julich K, Blenis J. Cell. 2008;133:303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valencia P, Dias AP, Reed R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800250105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guang S, Felthauser AM, Mertz JE. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6303. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6303-6313.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hung LH, et al. RNA. 2008;14:284. doi: 10.1261/rna.725208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.We thank A. Weiss for the JSL1 cell line, E. Kieff for BJAB and BL41 cells, B. North for the lentiviral expression plasmid, and the RNAi Consortium at the Broad Institute for providing the plasmids to produce the splicing factor library. We thank C. Moita for assistance in assembling the library and A. Astier and D. Hafler for aid in developing the protocol for infecting and silencing genes in primary human T cells. We thank K. Eger and D. Unutmaz for the naïve and activated cord blood samples. We thank J. Burke at Biotique for assistance with the array analysis. This work was supported by NIH grants CA42471, AI40127, and AI44432 to A.R., and U19 AI070352, R21 AI071060, and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency grant W81XWH-04-C-0139 to N.H. S.O. is supported by postdoctoral training grant T32 HL066987 from the Joint Program in Transfusion Biology and Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.